CHAPTER 3 TIME VALUE OF MONEY CONCEPTS

CASE STUDY

Justin Williams, age 37, has just sold his business. His information technology firm—offering a central locus for data on state income tax credits—was acquired by a large national accounting firm for $2.5 million net after tax. Justin will receive a lump sum payment for his business at the end of three years, but as a condition of the purchase, Justin must work for the accounting firm for three years at his current salary of $150,000 per year. Once Justin’s three-year commitment is over, he no longer plans to work because he feels that he will be financially independent. He is certain that a 5 percent after-tax return on his investments over his lifetime is a reasonable expectation.

Like many entrepreneurs, Justin worked days, nights, and weekends to build the company and is looking forward to kicking back and relaxing. Justin plans to retire to a lake house—not yet purchased—and write the great American novel. He anticipates spending $500,000 to purchase the lake home and fix it up comfortably. Justin shares that life has been good to him, that he is happily single, and that he plans to live it to the fullest. And speaking of life: Justin plans to exceed his family’s longevity record of age 99 and make it to age 100.

Justin was referred to you by your Director of Information Technology, Eric Martinez, who has known Justin for over a decade and believes he will be a great client for the firm. Justin is meeting with you to

•enter into an engagement for asset management;

•create an investment policy statement; and

•obtain a referral to a Realtor to find a lake home.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

![]() Formulate time value of money solutions used for personal financial planning goals.

Formulate time value of money solutions used for personal financial planning goals.

![]() Determine the optimal time value of money calculation for various personal financial planning scenarios.

Determine the optimal time value of money calculation for various personal financial planning scenarios.

![]() Apply the basic functions of TVM and demonstrate how they are used to provide realistic expectations and solutions to specific personal financial planning needs.

Apply the basic functions of TVM and demonstrate how they are used to provide realistic expectations and solutions to specific personal financial planning needs.

![]() Calculate PV, NPV, IRR and serial payments, and apply these techniques to personal financial planning.

Calculate PV, NPV, IRR and serial payments, and apply these techniques to personal financial planning.

Introduction

Claude Lévi-Strauss once said, “The wise man doesn’t give the right answers, he poses the right questions.” Much of a personal financial planner’s job involves asking the right questions to understand a client’s situation and to provide him or her with accurate information. Without this goal, a personal financial plan becomes a ship without a destination and effective planning is rendered moot.

Personal financial planning requires an understanding of the application of the time value of money (TVM). The TVM concept allows the personal financial planner to conduct a preliminary assessment of the prospective client’s goals, and then to translate those goals into quantifiable dollar amounts.

Calculating TVM isn’t difficult as long as you have the right tools and the right information. In this chapter, we’ll start off by discussing the available tools. From there we move on to the more difficult concept: obtaining the right information. Clients will not approach you with a list of inputs ready for calculations. Rather, they will discuss their financial situation and goals with you. To perform TVM calculations, you will need to determine the correct information based on these discussions. In some cases, clients will tell you exactly what you need to know; in other cases, you will need to ask the right questions to elicit the information you need. The bulk of this chapter will be spent walking you through client scenarios so that you can see exactly how to obtain the information needed to perform TVM calculations.

Tools for Calculating Time Value of Money

There are two main tools for calculating the time value of money: computer software and financial calculators. Calculators gained popularity years ago, before computers were common. Today, of course, computers are ubiquitous and used for almost every application. If you have a smartphone, you’re carrying an extremely powerful, useful computer that’s likely smaller than the standard calculator. There are plenty of computer programs that will perform TVM calculations, and, in fact, most personal financial planners use them. Both tools are fine, but we prefer financial calculators for their flexibility, ease of use, and, in some cases, greater functionality. Although we prefer and recommend the use of financial calculators, our discussion in the rest of the chapter will apply to both calculators and software.

WHICH CALCULATOR?

We’ve recommended that you should use a calculator for FVM calculations, but which one should you use? There are well over a dozen quality financial calculators available for use by personal financial planners, any one of which would be fine. It’s not our goal to recommend any particular calculator, and we have no intention of making any kind of official endorsement. We will note, though, that many personal financial planners choose to use the HP 12c and the Texas Instruments (TI) BAII.

Why these two calculators? In the majority of states, the following designations allow an individual to register as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) without taking the Uniform Investment Adviser Law Examination (Series 65): Personal Financial Specialist (CPA/PFS), Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA®); Certified Financial Planner (CFP®); and Chartered Financial Consultant (ChFC®). Each of these designations has a national examination that requires the use of a financial calculator. The HP 12c and the TI BAII financial calculator were approved for each of these examinations. So, you might want to stick with them. Again, this doesn’t represent an endorsement on our part.

Whether you choose to use a financial calculator, as we recommend, or a TVM program, you would be wise to equip yourself to perform TVM calculations during the initial engagement for two basic reasons: efficiency, and establishing realistic expectations.

EFFICIENCY

Efficiency is the simpler of the two reasons to illustrate:

A potential client would like to start a Section 529 college funding plan for his child’s education. As part of the process, the potential client will interview two personal financial planners. The first of the prospective planners meets with the client and gathers all of the necessary data: child’s current age, present cost of college, number of years the child is expected to be in college, inflation rate for college costs, and the rate of return on a hypothetical investment portfolio for college funding. Not knowing the scope of the engagement and having only brought material to take notes, the first planner then schedules a second appointment to present his findings. The second personal financial planner gathers the same data. However, the second planner presents the results within two minutes at the initial consultation using a financial calculator that was brought to the interview.

Now place yourself in the role of the prospective client. If all certifications, credentials, and fees between the two advisers are equal, which personal financial planner would you select? Which of the two demonstrated a higher degree of competence and provided an immediate solution addressing the client’s need? Simple logic dictates that the second of the two personal financial planners is more efficient.

ESTABLISHING REALISTIC EXPECTATIONS

Like Justin from the case study, when potential clients meet with a personal financial planner, they have no idea as to whether or not their goals are realistic or achievable. One of the functions of the personal financial planner is to establish realistic expectations in order to define the potential scope of engagement. Competent use of a financial calculator or TVM software provides the personal financial planner—and the potential client—with reasonable estimates in order to establish realistic goals for the engagement.

The Statement on Standards in Personal Financial Planning Services (SSPFPS) No. 1, par. 31, explains:

When analyzing information obtained while performing the engagement, the member should … evaluate the reasonableness of estimates and assumptions that are significant to the plan.

The potential client brings his or her own estimates and assumptions to the engagement. If the personal financial planner is able to address these assumptions at the initial consultation, the planner demonstrates

•a level of knowledge of PFP principles and theory;1 and

•mutual discovery as the “estimates and assumptions” are validated or invalidated.

Fundamental Time Value of Money Functions

There are five basic TVM functions: Number of Periods [n]; Interest [i]; Present Value [PV], Payment [PMT] and Future Value [FV]. Table 3-1 provides a breakdown of the meaning of these functions.

| TABLE 3-1 | FUNDAMENTAL TIME VALUE OF MONEY FUNCTIONS |

FUNCTION |

MEANING |

PLANNING CONCEPT |

n |

Number of periods | Years, months, days |

i |

Interest per period | Interest, inflation |

PV |

Present Value | Amount financed, amount deposited at beginning of period |

PMT |

Payment per period | Cash received or disbursed |

FV |

Future Value | Financial goal, amount received at end of period |

Understanding these five functions and the relationships among them is essential because it will allow you to determine or calculate most personal financial planning problems quickly and logically without memorizing formulas.

Before we take a look at each of these functions in detail, we should note that these functions are more than just technical information to help you perform calculations. You can certainly look at them that way, but to really understand their value you should see them as directly linked to client goals. Here are some sample client goals linked directly to the five functions:

•Determining the number of years to retire a debt [n]

•Determining the return on an investment portfolio [i]

•Determining the amount to provide for survivor income needs (Present Value [PV])

•Determining annual deposits for a child’s education (Payment [PMT])

•Determining the value of retirement assets at age 67 [FV]

If you see these functions as extensions of the client’s goals, you’ll provide better service.

TVM TIPS

•TVM calculations will not work unless at least three of the five basic TVM functions are entered. If only two functions are present, then the calculation does not involve the time value of money.

•Memorize, and maintain, the order in which the functions are presented: n, i, PV, PMT, FV. If you are consistent in this discipline, you can avoid errors that are the result of missed or overlooked functions.

PRESENT VALUE (PV)

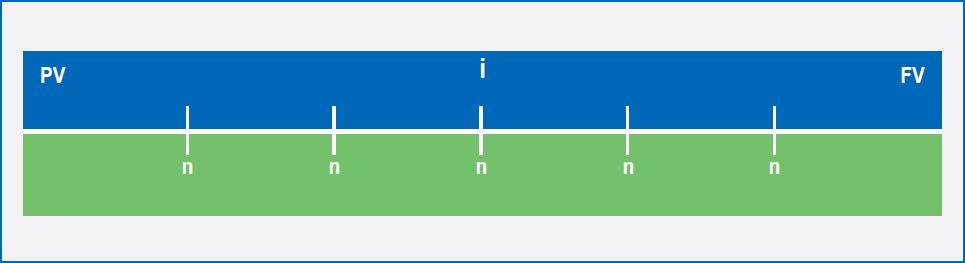

The present value [PV] of a single sum is the current worth of a future sum of money or stream of cash flows. Present value is the future value that has been discounted by the given number of periods [n] and the given interest rate [i]. The concept of present value is critical to the personal financial planning process because it determines the current value of a future sum. The interest rate used in determining the present value is often referred to as the opportunity cost. The following illustration is a visual representation of fundamental TVM calculations. The horizontal line is a timeline, and along the continuum are periods [n]. There are five periods illustrated. Above the timeline is the interest [i] being credited or charged during the periods. The beginning of the timeline is the present value [PV] and the end of the timeline is the future value of the asset.

When entering the present value of a number, it is almost always entered as a negative input. The exception to this rule of thumb would be calculations involving amortization, such as mortgages and automobile loans.

If you make a withdrawal from your deposit account, it is entered as a negative number; if you make a deposit into your deposit account, it is a positive number. Now, what if you want to solve for the future value [FV] of a hypothetical investment account five years [n] from now if that investment is presently worth $10,000 [PV] and is growing annually at 6 percent [i]? The beginning value of the hypothetical investment account began with the investor drafting the $10,000 [PV] from his deposit account into his investment account.

PERIODS (n)

The number of compounding periods [n] represent time in the TVM calculations. In many fact patterns, [n] may very well represent a number of years, such as four years of college, 30 years of mortgage payments, or three years of an apartment lease. However, periods may also represent some other division of time.

•Days—360 days in a bond year

•Months—180 months in a 15-year mortgage

•Semi-annual—2 coupon payments per bond year

Remember that n represents the number of compounding periods and not the number of years. You need to be alert to the specific facts and circumstances of a case. Occasionally, the number of periods needs to be inferred from the facts presented. For example, you may infer that the number of periods for a 30-year bond is 60, because the traditional bond pays two coupons per year (30 × 2 = 60 coupon payments over the life of the bond).

INTEREST (i)

Interest [i] is the growth rate of an asset. The interest could be

•appreciation in real estate;

•interest earned by a certificate of deposit (CD); or

•the projected rate of return on an individual security or a portfolio of securities.

RULE OF 72

The Rule of 72 comes up in any review of the function of [i] in TVM calculations. The Rule of 72 provides a rule of thumb for approximating how long [n] it will take a hypothetical investment to double in value at an assumed annual interest rate [i] or to determine the required rate of return [i] for an investment to double in value.

To calculate the number of years required for an investment to double in value, 72 is divided by the assumed annual interest rate. For example:

Alice invests $1,000 [PV] in an S&P 500 exchange traded fund (ETF). She is confident that the ETF will grow at an 8 percent [i] annual compounded return. She wants to sell the ETF when it doubles in value—$2,000 [FV]. How many years [n] will it take for her investment to double?

The solution is provided by using the Rule of 72: divide 72 by the anticipated annual interest rate of 8. The solution: The ETF will double in value in approximately nine years.

To calculate the interest rate [i] required for the ETF to double in value, divide 72 by the number of years. Alice invests $1,000 and she wants to double her investment in six years. Using the Rule of 72: divide 72 by six, the required number of years. Alice needs to earn 12 percent, compounded annually, to double her investment in six years.

PAYMENT (PMT)

Payment (PMT) in TVM calculations indicates a series of equal periodic payments. Payments may be money received—such as survivor income from a life insurance settlement; disability income payments; or required minimum distributions from an individual retirement account—or a payment may be money “paid out”—such as an automobile or mortgage payment to a creditor. Payment [PMT] may be a negative or a positive input. The decision as to which to use is based on whether the cash flow (the payment) is being withdrawn or deposited. In personal financial planning, the selection is intuitive and fairly straightforward. If you are struggling, ask yourself, “Is the money leaving the checking account or is it being deposited into the checking account?”

It can be easy to mistake present value [PV] with payment [PMT]. Note that present value is a singular event, one point in time. Payments are a series of ongoing equal payments over two or more periods. Both may be a negative or positive input. Consider negative versus positive input:

Positive—Funds that are deposited into the client’s checking account, such as the following:

•CD interest or bond coupons received by the client

•Dividends received by the client

•Pension or IRA distributions received by the client

•Withdrawals from mutual funds received by the client

Negative—Funds that are withdrawn from the client’s checking account, such as the following:

•401 (k) elective deferrals

•Investments into bonds, mutual funds, stocks (This one is tricky; remember, you are withdrawing from somewhere to put into the investment.)

•Mortgage payments

•Payments to a credit card

•Deposits into a 529 college savings plan

FUTURE VALUE (FV)

The future value [FV] of a single sum is the value of a single deposit [PV] that is compounded for a given number of periods [n] at a given interest rate [i]. The phrase single sum indicates that a single payment or deposit was made at the beginning of the period. Compounding means that interest is earned on the cumulative interest from previous periods. Said another way, when a deposit is made, interest is earned on that deposit not only in the initial period, but in subsequent periods as well. This process of paying interest on a previous period’s interest is called compounding. FV is almost always a positive number; however, it can be zero. The future value is the final cash flow or the compounded value of a series of prior cash flows.

MODE

When performing basic TVM calculations, you will need to know the five functions we have discussed, as well as one calculator or program function: mode. Financial calculators and programs all require input of one of two modes, either Begin [BEG] or End [END]. Begin or end “tells” the financial calculator or program whether interest is to be paid/charged at the Beginning or the End of the period [n].

Begin Mode

Loan payments (automobile, consumer debt, mortgage, and so on) are always in begin mode. The loan proceeds are “advanced” and the first payment is not due until the end of the first compounding period. Interest is accruing for the first compounding period and is technically being added to the debt. It is this accrued interest, plus the loan amount, that becomes the principal sum upon which the payment is figured. Examples of calculations using begin mode include the following:

•College tuition—the college wants the tuition at the beginning of the semester attended

•Retirement benefits—retirees want their checks at the beginning of the period

•Survivor income needs—survivors want their checks at the beginning of the period

End Mode

Financial planners like to joke that financial calculators and programs live in the end mode because if consumers had a choice, they would make all of their loan payments at the end of the month. Examples of calculations using end mode include the following:

•Automobile loan payments

•Bond interest

•Mortgage payments

EXAMPLES

The best way to understand these concepts is through examples. We’ve gathered a number of examples for you organized by the primary function involved. To help you understand how the functions relate to real world issues that arise in engagements, we have embedded the functions directly in the example text. This way you can start to associate the functions with actual client language. You don’t want to reduce everything the client says to nothing more than a series of functions, but understanding what language corresponds to what function will help you provide information to your clients more quickly and easily.

Present Value Example

How much must Adam Jones invest [PV] in an intermediate bond fund so that in four years [n] it will grow to $7,000 [FV]? The average annual compounded rate of return for the fund is 8.7757 percent.

In order to avoid mistakes, remember to consistently order your functions. The order of functions is n, i, PV, PMT, FV. In the fact pattern presented, the practitioner is solving for [PV]. It is therefore placed last in the sequence of functions.

mode = begin

n = 4

i = 8.7757%

FV = $7,000

PV = $5,000

Periods Example

Bob wants to buy a new automobile. He anticipates that at the time of purchase he will need a down payment of $10,000 [FV]. The credit union is currently paying 2 percent [i] on money market demand accounts. He is able to set aside $3,000 [PMT] per year toward this goal. How long will it take Bob to save up his down payment (solve for [n])?

mode = begin

i = 2%

PMT = -$3,000

FV = $10,000

n = 4 (rounds up to the next whole integer from 3.2591)

Interest Example 3

Dante wants to purchase a new home. He anticipates that at the time of purchase he will need a down payment of $30,000 [FV]. He is able to set aside $7,000 [PMT] per year toward this goal. He wants to buy the home in 4 [n] years. What rate of return [i] is required to achieve his goal?

mode = end

n = 4

PMT = -$7,000

FV = $30,000

i = 4.6181%

Payment Example

Carolyn just received a raise in salary. The raise will provide a net after-tax benefit of $12,000 per year. She wants to save this amount [PMT]—out of sight, out of mind—and add it to her retirement nest egg. Carolyn plans to retire in 25 years [n] and she is confident in a 4 percent after-tax return [i] on her investment. How much will her “nest egg” be worth at retirement [FV]?

mode = end

n = 25

i = 4%

PMT = -$12,000

FV = $499,750.8994

Future Value Example

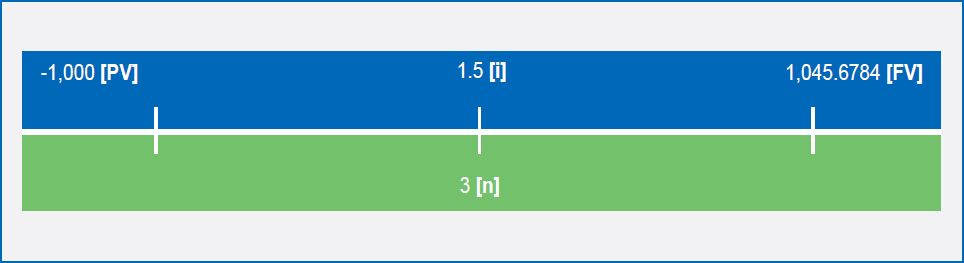

David was required to make a deposit against potential damages when he signed the lease for his apartment. The amount of the deposit was $1,000 [PV]. The term of the lease was for three years [n]. Current interest being annually credited on a three-year CD is 1.5 percent [i]. If David had not been required to make a deposit against damages for his apartment lease, and instead purchased the three-year CD, what would its value be at the end of three years [FV]?

mode = begin

n = 3

i = 1.5%

PV = -$1,000

FV = $1,045.6784

Unequal Cash Flows

Now that we understand basic TVM concepts and calculations, it’s time to move on to something a bit more advanced: unequal cash flows. All of the calculations we’ve seen so far involved single sums and equal periodic payments, or a combination of the two. However, many times cash flows to and from an investment are not equal or do not occur at regular intervals. For example, real estate purchased for a dollar amount [PV] and sold at a future date may have positive cash flow (rent) or negative cash flow (repairs, property taxes, and so on) [PMT]. This is what’s known as unequal cash flows.

Calculations involving unequal cash flows are based upon the TVM concepts previously presented; however, they involve some new functions. Table 3-2 shows the new functions necessary for unequal cash flow calculations.

| TABLE 3-2 | ADVANCED TIME VALUE OF MONEY FUNCTIONS |

FUNCTION |

MEANING |

PLANNING CONCEPT |

IRR |

Internal Rate of Return | The return that makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows from an investment equal to zero |

NPV |

N et Present Value | The difference between the present value of cash inflows and the present value of cash outflows at an assumed interest rate |

CFo/CF |

Cash Flow O / Cash Flow | Initial cash flow or outlay for an investment |

CFi/CF |

Cash Flow in / Cash Flow | Cash flows in subsequent years for an investment |

CALCULATORS AND UNEQUAL CASH FLOWS

Many types of personal financial planning software don’t provide solutions for unequal cash flow calculations. As a result, some personal financial planners avoid this type of analysis for a client. That’s unfortunate because, as you will discover, there are many uses for unequal cash flow calculations in the personal financial planning process that are greatly advantageous to the client. The authors recommend either finding software that supports unequal cash flow calculations or using a financial calculator. Either way, be sure to write down all of the inputs to these calculations. There can be quite a lot of them in unequal cash flow calculations, and one mistake may require you to re-input all of your work.

In addition, the following rules apply when performing unequal cash flow calculations:

1. Cash inflows (CFi) to an investor (deposit into a bank, dividends, interest, rental income) must be input as a positive number. Cash outflows to an investor (repairs to a property, systematic investments, taxes paid, withdrawal from a bank account) must be input as a negative number. With the exception of an initial investment, when there is both a positive and a negative cash flow in the same period, the amounts must be entered as a net amount.

EXAMPLE

Ken owns an apartment as an investment. His rent received for the year was $12,000. His expenses for the year (insurance, property tax, and upkeep) were $10,000. Ken’s net cash flow is $2,000 and is input as a positive number (deposit into his bank account).

2. If there is no cash flow (either in or out) for a period, a zero must be entered for the cash flow for that period of the investment.

EXAMPLE

Ken owns an apartment as an investment. His rent received for the year was $10,000. His expenses for the year (insurance, property tax and upkeep) were $10,000. Ken’s net cash flow is zero and is input as a 0. No money was deposited into Ken’s bank account.

3. The initial cash outflow, typically the purchase of an investment, is referred to as Cash Flow 0 (CFo | CF). It must always be entered. If the initial investment amount is not known, it is entered as 0.

PRESENT VALUE

We have already seen basic present value calculations. However, present value (PV) works somewhat differently in unequal cash flow calculations. In these calculations, PV is also referred to as the discounted value and can be used to evaluate a long-term investment. The future cash flows from an investment are discounted at a given interest rate in order to determine the total present value (PV) of the long-term investment. PV is then the current worth or value of a future stream of cash flow at a specified rate of return.

Determining the appropriate interest rate is the key to properly valuing future cash flows. Typically, the greater the risk (the potential that future cash flows will not be paid to the investor), the greater the interest rate. Also, the longer the time period before the original investment is returned to the investor, the higher the interest rate will be, because time equals risk.

NET PRESENT VALUE

The difference between the total present value of the cash flows and the amount of the initial investment is the long-term investment’s net present value (NPV). If the NPV is positive, it means the investment’s rate of return is more than the required rate of return. If the NPV is negative, it means the investor’s rate of return is less than the required rate of return.

NPV is used to analyze the profitability of a projected investment. NPV is a direct measure of the cost of investing versus the profit from the investment. NPV measures the economic profit to be gained by making the investment. In order for an investment opportunity to be considered, it should be expected that the NPV will be greater than or equal to zero.

If the NPV is a positive number (greater than zero), this indicates the projected profit generated by the investment exceeds the anticipated cost of the investment. Generally, an investment with a positive NPV will be a profitable one and one with a negative NPV will result in a net loss.

INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN

The internal rate of return (IRR) is the interest rate that makes the NPV of all cash flows equal to zero. It represents the return a company would earn if it expanded or invested in itself, rather than elsewhere. An investor is looking for IRR to be equal to or greater than the required rate of return for their investment portfolio. IRR allows investors to view their investments by the investment’s rates of return and not the investment’s net present values. The IRR cannot be used to compare projects with different durations.

SERIAL PAYMENTS

All of the payments we calculated in the earlier part of the chapter were level payments—they remained the same (level) for each period. Serial payments increase in dollar amounts each year on a regular basis, in order to reflect the effects of inflation at a constant rate. A serial payment calculation is a helpful PFP tool for a client who is not currently able to invest the required level annual payment needed to achieve stated goals and whose income will be increasing in future years. It should be noted that a considerable assumption used when calculating serial payments is that inflation is constant throughout the term of the calculation.

The presumption made in serial payment calculations is that a client’s income will rise with inflation over time. The investor anticipates that increases in income earned will track with the increased serial payments. In early years, the initial serial payment will be less than the respective payment due if based on level payment calculations. In the later years of funding, the serial payments will be greater than the respective level payment due; however, the later serial payments will have the same purchasing power as the first serial payment.

EXAMPLES

As was the case with the basic TVM functions, the best way to understand unequal cash flow concepts is through examples. We have again gathered a number of examples organized by the primary function involved. In this case, though, because the functions are a bit more complicated, we have pulled out the various calculation inputs for you.

Present Value Example #1

A prospective PFP client comes to you with an investment statement. The first page of the statement, which contained the initial investment amount of a mutual fund purchased five years ago, is missing, and as a result the initial cash flow (CFo | CF) is -0-. The initial investment (present value) of the mutual fund can be determined based on the following information provided in the investment statement. The statement indicates that the five-year return for the investment was 10 (i) percent.

•Year 1: capital gain and dividend were $100 (CFj)

•Year 2: capital gain and dividend were $150 (CFj)

•Year 3: no capital gain or dividend paid and the client invested $1,000 (CFj)

•Year 4: no capital gain or dividend paid (CFj)

•Year 5: no capital gain or dividend paid and the client sold out of his position for $18,000 (CFj)

CALCULATORS AND PV VERSUS NPV

Note that when the initial investment amount is not known, it is entered as 0. Most calculators and even some programs require you to use the NPV key in your calculation even though you are solving for the PV of the future value of cash flows.

The prospective client paid $10,640.15 for the mutual fund five years ago.

Present Value Example #2

Brad Smith is considering the purchase of a real estate investment trust (REIT). The REIT’s prospectus projects positive cash flows (CFj) for Years 1, 2, and 3 of $6,000, $7,000, and $8,000, respectively. At the end of three years, Brad anticipates he will sell the REIT for $115,000 (CFj). He wants to make a return of at least 6 percent(i). How much should he pay for the REIT? Brad is solving for the price he should pay, so the initial cash flow (CFo | CF) is -0-.

The inputs for our calculation are as follows:

•CFj | CF in the year of the sale is the sum of $115,000 (sales price) + $8,000 (distribution) = $123,000.

Brad should not pay more than $115,163.52 for the REIT.

Present Value Example #3

A PV calculation may also be used to value a bond trade over the counter in the secondary market:

Tom and Susan Peters need an intermediate term bond to round out their investment portfolio’s asset allocation. How much should the Peters pay for a bond ($1,000 par value) with a 3 percent annual ($30 annual payment) coupon that matures in five years if comparable bonds are yielding 4 percent(i)? Like Brad from example #2, Tom and Susan are solving for the price they should pay, so the initial cash flow (CFo | CF) is -0-.

•CFj | CF in the year of redemption is the sum of $1,000 (par value) + $30 (coupon) = $1,030.

The Peters should not pay more than $955.48.

Net Present Value Example

Darren and Alice Johnson are in the information technology consulting business. Alice’s father just passed away and left her $100,000. They are considering investing her inheritance in a server farm owned by one of their clients. The client has a cash flow problem and has offered the Johnsons the following investment proposal: purchase an investment interest for $100,000 today; receive cash distributions of $6,000, $7,000, and $8,000 respectively over the next three years; and at the end of the third year the owner will purchase back the interest in the server farm for $115,000. Even though the owner is a client the Johnsons trust, they consider the investment to be risky. Darren and Alice feel that they should earn at least 12 percent on the investment in order to be fairly compensated for the investment risk. Should the Johnsons invest in the server farm?

The inputs for our calculation are as follows:

•CFj | CF in the year of the sale is the sum of $115,000 (sales price) + $8,000 (distribution) = $123,000.

The Johnsons should not invest in the server farm because their required rate of return (12 percent) will not be achieved by their client’s proposal. A negative NPV means the proposed investment will earn less than the Johnson’s required rate of return. If the NPV was a positive number, this would indicate the proposed investment would earn more than the Johnson’s required rate of return. The NPV result does not make the server farm a bad investment but, rather, indicates the Johnson’s required rate of return for the risk being undertaken will not be met.

Internal Rate of Return Example #1

Let’s return to the preceding net present value example. What is the actual internal rate of return (IRR) that Darren and Alice would receive based upon the proposal as presented by their client? The calculation is the same as that for NPV, but with one exception: Instead of solving for NPV, solve for IRR.

If the Johnsons had chosen to move forward with the investment in the server farm, the projected return on their three-year investment would have been 11.40 percent.

Internal Rate of Return Example #2

Steve collects, buys and sells antique automobiles. His wife, Candace, thinks he is losing money and that it’s all a waste of his time and their financial resources. On the other side of the equation, Steve calls his activity investing. Steve purchased an antique automobile six years ago for $30,000 and in the first year he spent $15,000 to repair it. His annual upkeep (storage, insurance, maintenance) for the automobile was $6,000. Steve just sold the automobile for $90,000. What is the average compound rate of return (IRR) that Steve earned on his investment?

The inputs for our calculation are as follows:

•CF0 | CF initial year $30,000 (purchase price) + $15,000 (repair) + $6,000 (annual upkeep) = $51,000.

•CFj | CF sale year $90,000 (sales price) - $6,000 (upkeep) = $84,000.

Steve earned an IRR of 2.72 percent on his investment in the antique car.

Internal Rate of Return Example #3

An IRR calculation may also be used for a stock:

What is the IRR for the following stock investment?

Purchase price $5,000 (CFo) End of Year 1 pays a dividend of $5 (CFi) End of Year 2 pays a dividend of $25 (CFi) End of Year 3 pays a dividend of $40 (CFi) End of Year 4 pays no dividend - 0 - (CFi) End of Year 5 investment is sold for $6,000 (CFi)

The investment yielded a 3.98 percent return over five years.

Serial Payment Example

Tom Jones hopes to be financially independent in 10 years. To achieve this goal, Tom needs to acquire an additional $500,000, in today’s dollars, in 10 years. It is assumed the inflation rate will average 3 percent over this period and that Tom’s investment portfolio will earn, on average, 7 percent during this same period of time. What payment should Tom invest at the end of the first year to fund his goal? Note that due to cash flow limitations, Tom cannot afford to invest more than $45,000 at this time.

We start by calculating the level payment that Tom would have to make. Recall from earlier in the chapter that we must start by first calculating the FV of $500,000 in today’s dollars. The inputs for our calculation are as follows:

n = 10

i = 3%

PV = $500,000

The solution to our calculation is that the FV is $671,958.19. Using this value, we can now solve for the PMT. The inputs to our calculation are as follows:

n = 10

i = 7%

FV = $671,958.19

Tom needs to make a payment of $48,634.66 each year. This is more than he can afford, so we now turn a serial payment calculation to determine his payments. The inputs for our calculation are as follows:

n = 4

i = 3.88352

FV = 500,000.0000

PMT = -41,870.9776 × 1.03 (to inflate for serial payment)

Tom starts with a payment of $43,127.11 for the first year. Each year, Tom will increase his payments for inflation. The second year payment will be $43,127.11 multiplied by the inflation rate of 3 percent or $44,420.92, and so forth. The lower payments are within Tom’s ability to make and thus motivate him to do what it takes to reach his financial independence retirement goal. Otherwise, by setting a payment amount that is not within his reach, he is susceptible to discouragement and potential failure of reaching his goal.

Chapter Review

The practice of personal financial planning requires an in-depth understanding of the time value of money (TVM), as well as proficiency with a financial calculator or computer program to perform TVM calculations. However, simply relying on computer software or a calculator to perform TVM calculations for clients places the personal financial planner at a disadvantage with other practitioners and advisers who have a familiarity with both the concepts behind the calculations and the tools used to perform them. Both areas of knowledge are necessary in order to establish realistic expectations and credibility for the client as a potential engagement is discussed.

For example, in an engagement discussion, a prospective client may present an unrealistic expectation as to income desired for financial independence. The practitioner with a knowledge of TVM and tools to perform the calculations during an engagement will be able to provide a more realistic set of expectations to the client. In doing so, the personal financial planner establishes credibility and sets the stage for the entire engagement.

Remember that TVM calculations will not work unless at least three of the five basic TVM factors are entered. If only two factors are present, then the calculation does not involve the time value of money. Also, memorize, and maintain, the order in which the TVM functions are presented: n, i, PV, PMT, FV. If the practitioner is consistent in this discipline, errors that are the result of missing or overlooked functions will not occur.

CASE STUDY REVISITED

Recall that Justin Williams is meeting with you because he just sold his information technology firm and is looking down the road to living comfortably off his investments. What is your initial response to Justin? How can you determine if he is really financially independent, as he claims, in the initial meeting? How would you help him with realistic expectations for the potential engagement?

Let’s start by reviewing Justin’s information:

•He sold his company for $2.5 million and plans to buy a lake house for $500,000, leaving him with a [PV] of $2 million. Remember to enter PV as a negative unless it is amortization.

•He is currently 37 (let’s round up to 40 for simplicity) and intends to live to 100, giving us an [n] of 60 (100-40).

•He feels that a 5 percent after-tax return on his investments is a reasonable expectation, giving us an [i] of 5 percent.

•Because we are solving for retirement income, the calculator should be in Begin Mode.

Using this information, we can calculate the time value of Justin’s money to see just how financially independent he really is. Let’s move on to our functions:

mode = begin

n = 60

i = 5%

PV = -$2,000,000

PMT = $100,625.1134

From these calculations, it looks as if Justin may well be right about being financially independent, assuming he’s comfortable living on an annual income of $100,625. Recall, though, that his current salary is $150,000 per year. You will need to ask Justin if a $50,000 reduction in annual funds works for him. Of course, you also have to determine whether a 5 percent annual return on his investment is actually a realistic expectation. If not, you will need to perform these calculations again with a new [i]. A lower after-tax return, of course, will yield a lower [PMT], reducing Justin’s annual income even further. Providing these types of calculations will help Justin have a more realistic set of expectations. Just be sure to do so gently—you might be breaking the news to him that the life of ease he’d envisioned for himself might not be quite as comfortable as he’d hoped!

ASSIGNMENT MATERIAL

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. If a prospective client hoped to accumulate $150,000 in 10 years, how much must he or she deposit today in an account that earns an annual return of 4 percent?

A. -100,614.91

B. 100,614.91

C. -101,334.63

D. 101,334.63

2. What will $250,000 grow to be in 13 years if it is in a 401(k) account with an average annual growth rate of 9 percent?

A. 766,451.15

B. 785,169.75

C. 795,119.63

D. 801,989.27

3. In meeting with a prospective client, you are presented with the following facts and circumstances: Twenty-five years ago, the client began an investment program. Today the investment is worth $350,000. The client made annual payments of $12,000 per year. What was the average annual rate of return over the period?

A. 1.25

B. 1.26

C. 1.52

D. 1.62

4. A prospective client has won the lottery. They have a choice of a lump sum payment of $10 million, or 20 annual installments of $600,000. The first payment will occur immediately. What is the present value of the stream of payments if the long bond rate is 5 percent?

A. 3,768,894.83

B. -3,768,894.83

C. 7,477,326.21

D. -7,477,326.21

5. A prospective client’s current standard of living is $100,000 per year. This person plans to retire in 15 years. What will the client’s future standard of living be if the average annual inflation rate is 3.5 percent?

A. 154,896.17

B. 167,534.88

C. 169,453.09

D. 172,354.11

6. A securities portfolio has the following characteristics:

| Year 1 beginning market value | $100,000 |

| Year 1 capital withdrawals | $ 4,000 |

| Year 2 capital withdrawals | $ 4,000 |

| Year 3 capital withdrawals | $ 4,000 |

| Year 3 market value | $ 110,000 |

Based on the portfolio characteristics, what is the rate of return for the securities portfolio?

A. 4.57 percent.

B. 4.67 percent.

C. 7.11 percent.

D. 9.18 percent.

7. Perry and Susan Williams just retired, moved to the lake and purchased fishing equipment and a bass boat for Perry’s new fishing business. The total investment in this business is $25,200—the cost of the equipment and boat. Susan told Perry he needed to earn at least a 10 percent return per year, because their retirement investment portfolio had averaged this amount over the years.

Surprisingly, and as a result of their investment in the equipment, they have actually been able to sell some of their catch to local restaurants at the marina. They have had positive cash flow, in excess of expenses, of $5,000; $5,500; $10,000; and $15,000 over a four-year period, respectively. At the end of their fourth year at the lake, they finally decide to really retire. The Williams sell all of their equipment to some local college students for $3,000. What is the NPV of the business?

A. -$3,512.02.

B. $3,512.02.

C. -$3,698.30.

D. $3,698.30.

8. From the previous question, what was the IRR on their investment in the business?

A. 11.37.

B. 12.47.

C. 15.27.

D. 16.57.

9. Robin and Christopher Bird want to purchase an intermediate term bond. How much should the Birds pay for a bond ($1,000 par value) with a 2 percent annual coupon that matures in five years if comparable bonds are yielding 3 percent?

A. $948.15.

B. $954.20.

C. $962.83.

D. $1,000.00.

10. Joan Salt won $250,000 from the lottery. She will receive $50,000 at the end of each year for the next five years. Her investment portfolio has an average annual return of 7 percent. What is the present value of the lottery winnings to Alice?

A. $102,504.94.

B. $185,476.23.

C. $205,009.87.

D. $250,000.00.

INTERNET RESEARCH ASSIGNMENTS

1. Survey the Internet for personal financial planning software. Options are available for practitioners and consumers. List two of each of the options and present your recommendations. Emphasis should be placed on the time value of money calculations and how they are utilized by the software.

2. What software is available to perform unequal cash flow analysis for personal financial planning?

3. Survey the Internet for online financial calculators. List at least three sites that you found to be of benefit and that you would recommend to your peers. Which of the TVM calculations are addressed by the website(s)?

4. The Rule of 72 has been in recorded use since the Renaissance. Survey the Internet to discover the origin of the rule’s origin. There are similar rules; list two of them and provide examples of their use.

5. Search the Internet for “lottery payments or lump sum.” If income taxes, irrational spending and mortality were not a consideration, what minimum rates of return are necessary in order to make the lump sum payment superior to the annual payment structure?