Chapter 21

Sample ETF Portfolio Menus

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Revisiting risk and return

Revisiting risk and return

![]() Employing Modern Portfolio Theory

Employing Modern Portfolio Theory

![]() Assessing what diversification means to you

Assessing what diversification means to you

![]() Recognizing that there are no simple formulas

Recognizing that there are no simple formulas

![]() Visualizing what your new portfolio will look like

Visualizing what your new portfolio will look like

If there is such a thing as a personal hell, and if, for whatever reason, I cheese off the Big Guy before I die, I’m fairly certain that I will spend eternity in either a Home Depot or a Lowe’s. The only real question I have is whether His wrath will place me in plumbing supplies, home décor, or flooring.

I’m not the handyman type. Even the words “home renovation” are enough to send shivers up my spine. The last thing I built out of metal or wood — a car-shaped napkin holder — was in shop class at Lincoln Orens Junior High School. I brought the thing home to my mother, and she said, “Oh, Russell, um, what a lovely birdhouse.”

And yet, despite my failed relationship with power tools, there is one kind of construction that I absolutely love: portfolio construction.

I enjoy crafting portfolios not only because it involves multicolored pie charts (I’ve always had a soft spot for multicolored pie charts) but also because the process involves so much more than running a piece of wood through a jigsaw and hoping not to lose any fingers. Portfolio construction is — or should be — a highly individualized, creative exercise that takes into consideration many factors: economics, history, statistics, and psychology among them.

The ideal portfolio (if such a thing exists) for a 30-year-old who makes $75,000 a year is very different from the portfolio for a 75-year-old whose income is $30,000 a year. The optimal portfolio for a 40-year-old worrywart differs from the optimal portfolio for a 40-year-old devil-may-care type. The portfolio of dreams following a long bull market when interest rates are low may look a wee bit different from a prime portfolio following a bear market with high interest rates.

Every financial professional I know goes about portfolio construction in a somewhat different way. In this chapter, I walk you through the steps that I take and that have worked well for me. I don’t mean to present my way as the only way, so I also mention an alternative strategy (see the sidebar, “Dividing up the pie either conservatively or aggressively by industry sector,” toward the end of the chapter).

Needless to say (because this is, after all, a book about exchange-traded funds), my primary construction materials are ETFs, as I believe they should be for most investors. My portfolio-building tools involve some sophisticated Morningstar software, my HP 12C financial calculator, a premise called Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), a statistical phenomenon called reversion to the mean, and various measures of risk and return. But rest assured that this isn’t brain surgery, or even elbow surgery. You can be a pretty good portfolio builder yourself by the time you finish this chapter.

So please follow along. I promise you that nothing you are about to see will resemble either a napkin holder or a birdhouse!

So, How Much Risk Can You Handle and Still Sleep at Night?

The first questions I ask myself — and the first questions anyone building a portfolio should ask — are these:

- How much return does the portfolio-holder need to see?

- How much volatility can the portfolio-holder stomach?

Very few things in the world of investments are sure bets, but this one is: The amount of risk you take or don’t take will have a great bearing on your long-term return. You simply are not going to get rich investing in bank CDs. On the other hand, you aren’t going to lose your nest egg in a single week, either. The same cannot be said of a tech stock — or even a bevy of tech stocks wrapped up in an ETF.

A well-built ETF portfolio can help to mitigate risks but not eliminate them. Before you build your portfolio, ask yourself how much risk you need to take to get your desired return…and take no more risk than that.

A few things that just don’t matter

Before I lay out what matters most in determining appropriate risk and appropriate allocations to stocks, bonds, and cash (or stock ETFs and bond ETFs), I want to throw out just a few things that really shouldn’t enter into your thinking, even though they play into many people’s portfolio decisions:

- The portfolio of your best friend, which has done great guns.

- Your personal feelings on the current administration, where the Fed stands on the prime interest rate, and which way hemlines on women’s dresses are moving this fall.

- The article you clipped out of Lotsa Dough magazine that tells you that you can earn 50 percent a year by investing in…whatever.

Listen: Your best friend may be in a completely different economic place than you are. Their well-polished ETF portfolio, laid out by a first-rate financial planner, may be just perfect for them and all wrong for you.

As far as the state of the nation and where the Dow is headed, you simply don’t know. Neither do I. (It was once argued that the stock market moves up and down with the hemlines on women’s dresses…or whether an NFC or AFC team wins the Super Bowl this year.) The talking heads on TV pretend to know, but they don’t know squat. Nor does the author of that article in the glossy magazine (filled with ads from fund companies) that tells you how you can get rich quickly in the markets. The secrets to financial success cannot be had by forking over $4.95 for a magazine.

(Whenever I read about some prognosticator suggesting a handful of stocks or mutual funds for the coming year, I Google them to see what projections they made a year prior. Then I check to see how their picks have done. You should do the same! Invariably, my dog Zoey, the killer poodle, could do a better job picking stocks.)

On the other hand, don’t pooh-pooh a 7 to 8 percent return. Compound interest is a truly miraculous thing. Invest $20,000 today, add $2,000 each year, and within 20 years, with “only” a 7.5 percent return, you’ll have $171,566. (If inflation is running in the 3 percent ballpark, that $171,566 will be worth about $110,000 in today’s dollars.)

The irony of risk and return

In a few pages, I provide you with some sample portfolios appropriate for someone who should be taking minimal risk as opposed to someone who should be taking more risk. At this point, I want to digress for a moment to say that in a perfect world, those who need to take the most risk would be the most able to take it on. In the real world, sadly ironic though it is, those who need to take the most risk really can’t afford to.

Specifically, a poor person needs whatever financial cushion they have. They can’t afford to risk the farm (not that they have a farm) on a portfolio of mostly stocks. A rich person, in contrast, can easily invest a chunk of discretionary money in the stock market, but they really don’t need to because they’re living comfortably without the potential high return. It just isn’t fair. Yet no one is to blame, and nothing can be done about it. It is what it is.

Let’s move on.

The 25x rule

Whatever your age, whatever your station in life, you probably wouldn’t mind if your investments could support you. But how much do you need in order for your investments to support you? That’s actually not very complicated and has been very well studied: You need about 25 times whatever amount you expect to withdraw each year from your portfolio, assuming you want that portfolio to have a good chance of surviving at least 20 to 25 years.

That is, if you need $40,000 a year — in addition to Social Security and any other income — to live on, you should have $1 million in your portfolio when you retire, assuming you retire in your mid-60s. You can have less, but you may wind up eating too far into the principal if the market tumbles — in which case you should be prepared to live on less, or get a part-time job.

(Factor in the value or partial value of your home only if it is paid up and if you foresee a day when you can downsize.)

The rationale behind the 25x Rule is this: It allows you to withdraw 4 percent from your portfolio the first year, and then adjust that amount upward each year to keep up with inflation. The studies show that a well-diversified portfolio from which you take such withdrawals has a good chance of lasting at least 20 years, which is how long you may need the cash flow if you retire in your 60s and live to your mid-80s.

If you think you might live beyond your mid-80s — and especially if you’re part of a couple, there’s a good chance that one of you will live beyond your mid-80s — then you might want more than 25 times. If you want to retire prior to your mid-60s, then having more than 25 times your anticipated annual withdrawals would be an excellent idea. It would also be an excellent idea to limit your initial withdrawal, if you can, to 3.5 percent a year, just in case you live a long life. If you want to play it really safe, limit your withdrawal to 3 percent.

In truth, I’d much rather see you have 30 times your anticipated yearly withdrawals in your portfolio before you retire. But for many Americans who haven’t seen a real pay increase in years, this is indeed a lofty goal. For that reason, I say go with 25 times, but be prepared to tighten your belt if you need to.

If you have your 25 times (or better yet, 30 times) annual cash needs already locked up or close to it, and you’re thinking of giving up your day job soon, you should probably tilt toward a less risky ETF portfolio (more bond ETFs). After all, you have more to lose than you have to gain. (See the upcoming sidebar, “Russell’s ‘today and tomorrow’ portfolio modeling technique,” for more on my suggestion that you should have not one but two model portfolios: one for right now, and one for the future.) You do need to be careful, however, that your investments keep up with inflation. Savings accounts are unlikely to do that.

If you have way more than 30 times annual expenses, congratulations! You have many options, and how much risk you take will be a decision that’s unrelated to your material needs. You may, for example, want to leave behind a grand legacy, in which case you might shoot for higher returns. Or you may not care what you leave behind, in which case leaving your money in a tired savings account, or “investing” in a high-performance but low-yielding Ferrari, wouldn’t make much difference.

Other risk/return considerations

I doubt I can list everything you should consider when determining the proper amount of risk to take with your investments, but here are a few additional things to keep in mind:

- What is your safety net? If worse came to worst, do you have family or friends who would help you if you got in a real financial bind? If the answer is yes, you can add a tablespoon of risk.

- What is your family health history? Do you lead a healthy lifestyle? These are the two greatest predictors of your longevity. If Mom and Dad lived to 100, and you don’t smoke and you do eat your vegetables, you may be looking at a long retirement. Add a dollop of risk — you’ll need the return.

- How secure is your job? The less secure your employment, the more you should keep in nonvolatile investments (like short-term bonds or bond funds); you may need to draw from them if you get the pink slip next Friday afternoon.

- Can you downsize? Say you are close to retirement, and you live in a McMansion. If you think that sooner or later you will sell it and buy a smaller place, you have some financial cushion. You can afford to take a bit more risk.

The limitations of risk questionnaires

Yes, I give my clients a risk questionnaire. And then I go through it with them to help them interpret their answers. Lots of websites offer investment risk questionnaires, but instead of having anyone interpret the answers, a computer just spits out a few numbers: You should invest x in stocks and y in bonds. Yikes!

For example, here’s one question that I saw on a web questionnaire: Please rate your previous investment experience and level of satisfaction with the following six asset classes. And then they listed money market funds, bonds, stocks, and so on.

I had a client named Jason who was a 38-year-old with a solid job and no kids. After taking an online questionnaire, he was told he should be invested almost entirely in money market funds and bonds based on his previous “very low” satisfaction with stocks and stock mutual funds. This young man definitely should not invest in any stocks or stock funds, the computer-generated program told him, because of his “very low” satisfaction with the funds he had invested in previously.

Oh, jeesh. The reason Jason had “very low” satisfaction with stocks and stock funds is that he got snookered by some stock broker (posing as a “financial planner”) into buying a handful of full-load, high-expense-ratio, actively managed mutual funds that (predictably) lost him money. That experience should have no bearing on the development of this young man’s portfolio, which should have the lion’s share invested in stock ETFs or mutual funds.

What I’m saying is that after reading this book, if you aren’t too certain where you belong on the risk/return continuum, perhaps you should hire an experienced and impartial financial advisor — if only for a couple of hours — to review your portfolio with you. I write more about seeking professional help in Chapter 26.

Keys to Optimal Investing

When you have a rough idea of where you should be riskwise, your attention should turn next to fun matters such as Modern Portfolio Theory, reversion to the mean, cost minimization, and tax efficiency. Please allow me to explain.

Incorporating Modern Portfolio Theory into your investment decisions

The subject I’m about to discuss is a theory much in the same way that evolution is a theory: The people who don’t believe it — and, yes, there are some — are those who decide to disregard all the science. Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) says that if you diversify your portfolio — putting all kinds of eggs into all kinds of baskets — you reduce risk and optimize return.

MPT has been challenged. At times, there are stretches of days, even weeks and months, when different asset classes — U.S. stocks, foreign stocks, bonds, commodities, and real estate — may all move up and down nearly in lockstep. This was the case, unfortunately, in the last serious bear market — 2008. Like a flock of geese, just about every investment you could imagine headed south at the same time.

While correlations can change over time — and lately, the major asset classes have shown alarmingly high rates of correlation — you shouldn’t simply scrap the idea that diversification and the quest for noncorrelation are crucial. However, you may want to be cautious of too much reliance on diversification. Yes, you can diversify away a lot of risk. But you should also have certain low-risk investments in your portfolio, investments that hold their own in any kind of market. Low-risk investments include FDIC-insured savings accounts; money market funds; short-term, high-credit-quality bonds; and bank CDs.

Minimizing your costs

Most ETFs are cheap, which is one of the things I love about them. The difference between a mutual fund that charges 1 percent and an ETF that charges 0.1 percent adds up to a lot of money over time. One of my favorite financial websites, www.moneychimp.com, offers a fund-cost calculator. Invest $100,000 for 20 years at 8 percent and deduct 0.1 percent for expenses; you’re left with $457,540. Deduct 1 percent, and you’re left with $386,968. That’s a difference of $70,571. The after-tax difference, given that most ETFs (or at least the ones I tend to recommend) are highly tax-efficient index funds, would likely be much greater.

Because the vast majority of ETFs I’m recommending fall into the super-cheap to cheap range (generally 0.03 to 0.20 percent), the differences among ETFs won’t be quite so huge. Still, in picking and choosing ETFs, cost should always be a factor. And that is especially true with bond funds during these days of pathetically low interest rates. Pay more than 0.20 percent for a short-term Treasury fund and you are likely to see no return for the coming months!

Striving for tax efficiency

Keeping your investment dollars in your pocket and not lining Uncle Sam’s is one big reason to choose ETFs over mutual funds. ETFs are, by and large, much more tax efficient than active mutual funds. But some ETFs are going to be more tax efficient than others. I provide in-depth coverage of this issue in Chapter 24 where I talk about tax-advantaged retirement accounts, such as Roth IRAs.

For now, let me say that you must choose wisely which ETFs get put into which baskets. In general, high-dividend and interest-paying ETFs (REIT ETFs, taxable bond ETFs) are best kept in tax-advantaged accounts.

Timing your investments (just a touch)

If you’ve read much of this book already, by now, you realize that I’m largely an efficient market kind of guy. I believe that the ups and downs of the stock and bond market — and of any individual security — are, in the absence of true inside information, unpredictable. (And trading on true inside information is illegal.) For that reason, among others, I prefer indexed ETFs and mutual funds over actively managed funds.

However, that being said, I also believe in something called reversion to the mean. This is a statistical phenomenon that colloquially translates to the following: What goes up must come down; what goes waaaay up, you need to be careful about investing too much money in.

At the time I’m writing this, for example, large-cap growth stocks, especially tech stocks like Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), and Tesla, have been flying high for several years. Real estate has also been doing very, very well. These are good reasons why you may want to be just a wee bit cautious about overstocking your portfolio in these particular asset classes.

I’m not suggesting that you go out and buy any ETF that has underperformed the market for years, or sell any ETF that has outperformed. But to a small degree, you should factor in reversion to the mean when constructing a portfolio.

Please don’t go overboard. I’m suggesting that you use reversion to the mean to tweak your portfolio percentages very gently — not ignore them! This “going-against-the-crowd” investment style is popularly known as contrarian investing.

Finding the Perfect Portfolio Fit

Time now to peek into my private world, as I reveal some of the ETF-based portfolios I’ve worked out for clients over the years (and updated, of course, as some newer ETFs proved to be superior to the old). You should look for the client that you most resemble, and that example will give you some rough idea of the kind of advice I would give you if you were my client. All names, of course, have been changed to protect privacy. For the sake of brevity, I provide you with only a thumbnail sketch of each client’s financial situation.

Considering the simplest of the simple

I include (in order of appearance) large-cap stocks, small-cap stocks, international stocks (large and small), and bonds (both conventional and inflation-adjusted).

This portfolio can be tailored to suit the aggressive investor who can deal with some serious ups and downs in the hopes of achieving high long-term returns; the conservative investor who can’t stand to lose too much money; or the middle-of-the-road investor. Keep in mind that you should always have three to six months in living expenses sitting in cash or near-cash (money markets, short-term CDs, Internet checking account, or very short-term high-quality bond fund). You should also have all your credit card and other high-interest debt paid up. The rest of your money is what you may invest.

Aggressive | Middle-of-the-Road | Conservative | |

|---|---|---|---|

Dimensional U.S. Core Equity Market (DFAU) | 24 percent | 16 percent | 12 percent |

Vanguard Small Cap ETF (VB) | 16 percent | 14 percent | 8 percent |

Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund ETF (VXUS) | 24 percent | 16 percent | 12 percent |

Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Small Cap Index ETF (VSS) | 16 percent | 14 percent | 8 percent |

BNY Mellon Core Bond ETF (BKAG) | 14 percent | 28 percent | 40 percent |

iShares ESG Aware 1–5 Year USD Corporate Bond (SUSB) | 6 percent | 12 percent | 20 percent |

Racing toward riches: A portfolio that may require a crash helmet

High-risk/high-return ETF portfolios are made up mostly of stock ETFs. After all, stocks have a very long history of clobbering most other investments — if you give them enough time. Any portfolio that is mostly stocks should have both U.S. and international stocks, large cap and small cap, and value and growth, for starters. If the portfolio is diversified into industry sectors (an acceptable strategy, as I discuss in Chapter 10), a high-risk/high-return strategy would emphasize fast-growing sectors such as technology.

Let’s consider the case of Jason, a single, 38-year-old pharmaceuticals salesman. You met him earlier in the chapter. Jason came to me after getting burned badly by several high-cost mutual funds that performed miserably over the years. Still, given his steady income of $120,000 and his minimal living expenses (he rents a one-bedroom apartment in Allentown, Pennsylvania), Jason has managed to sock away $220,000. His job is secure. He has good disability insurance. He anticipates saving $20,000 to $30,000 a year over the next several years. He enjoys his work and intends to work till normal retirement age. He plans to buy a new car (ballpark $40,000) in the next few months, but otherwise has no major expenditures earmarked.

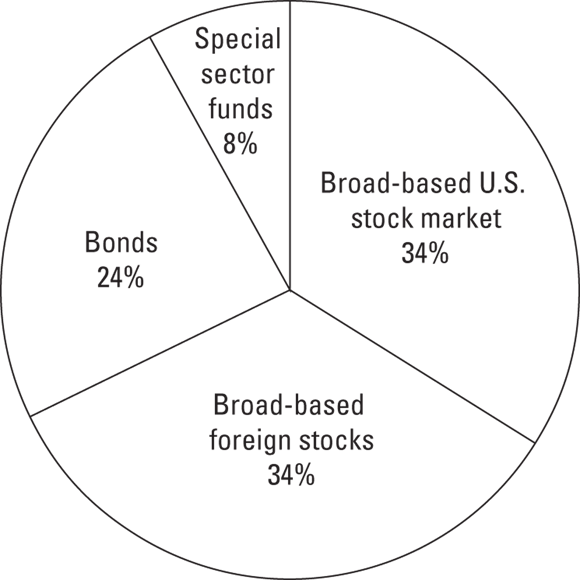

Jason can clearly take some risk. Following is the ETF-based portfolio that I designed for him, which is represented in Figure 21-1. Note that I had Jason put four to six months of emergency money, plus the $40,000 for the car, into a money market account, and that amount is not factored into this portfolio.

FIGURE 21-1: A portfolio that assumes some risk.

Also note that although this portfolio is made up almost entirely of ETFs, I do include one Pennsylvania municipal bond mutual fund to gain access to this asset class that’s not yet represented by ETFs. Municipal bonds issued in Jason’s home state are exempt from both federal and state taxes, which makes particular sense for Jason because he earns a high income and has no appreciable write-offs. See more about the role of municipal bonds in a portfolio in Chapter 15.

Finally, although this portfolio is technically 76 percent stocks and 24 percent bonds, I include a 4 percent position in emerging-market bonds, which can be considerably more volatile than your everyday bond. As such, I don’t really think of this as a “76/24” portfolio, but more like an “80/20” portfolio, which is just about as volatile a portfolio as I like to see.

Broad-based U.S. stock market: 34 percent

Dimensional U.S. Core Equity Market (DFAU) — 18 percent

Vanguard Small Cap Value ETF (VBR) — 8 percent

Vanguard Small Cap ETF (VB) — 8 percent

Broad-based foreign stocks: 34 percent

Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund ETF (VXUS) — 14 percent

iShares MSCI EAFE Value ETF (EFV) — 5 percent

Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Small Cap Index ETF (VSS) — 15 percent

Special sector funds: 8 percent

Vanguard REIT ETF (VNQ) — 4 percent

Vanguard International Real Estate ETF (VNQI) — 4 percent

Bonds: 24 percent

BNY Mellon Core Bond ETF (BKAG) — 10 percent

iShares ESG Aware 1–5 Year USD Corporate Bond (SUSB) — 5 percent

Vanguard PA Long-Term Tax-Exempt Admiral Fund (VPALX) — 5 percent

Vanguard Emerging Markets Government Bond ETF (VWOB) — 4 percent

Sticking to the middle of the road

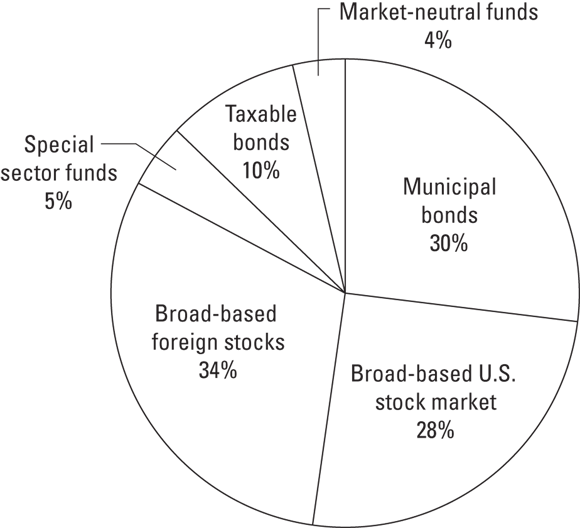

Next, I present Jay and Racquel, who are ages 64 and 63, married, and have successful careers. Even though they are old enough to be Jason’s parents, their economic situation actually warrants a quite similar high-risk/high-return portfolio. Both husband and wife, however, are risk-averse.

Jay is an independent businessman with several retail properties (valued at roughly $1.6 million); Racquel is a vice president at a major publishing house. Their portfolio: $1.1 million and growing. Within several years, the couple will qualify for combined Social Security benefits of roughly $93,500 — the highest a couple can collect if they start collecting at age 70. Racquel also will receive a fixed pension annuity of about $35,000. The couple’s goal is to retire within two to three years, and they have no dreams of living too lavishly; they will have more than enough money. The fruits of their investments, by and large, should pass to their three grown children and any charities named in their wills.

Being risk-averse, Jay and Racquel keep 30 percent of their portfolio in high-quality municipal bonds. They handed me the other 70 percent ($560,000) and told me to invest it as I saw fit. My feeling was that 30 percent high-quality bonds was quite enough ballast, so I didn’t need to add to their bond position by very much. I therefore constructed a portfolio of largely domestic and foreign stock ETFs. The size of their portfolio (versus Jason’s) warranted the addition of a few more asset classes, including a foreign-bond fund and a market-neutral fund.

I did not include any U.S. REITs, given that so much of the couple’s wealth is already tied up in commercial real estate. Figure 21-2 presents the portfolio breakdown.

FIGURE 21-2: A middle-of-the-road portfolio.

Municipal bonds: 30 percent

Broad-based U.S. stock market: 28 percent

Dimensional U.S. Core Equity Market (DFAU) — 16 percent

Vanguard Small Cap Value ETF (VBR) — 6 percent

Vanguard Small Cap ETF (VB) — 6 percent

Broad-based foreign stocks: 34 percent

Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund ETF (VXUS) — 10 percent

iShares MSCI EAFE Value ETF (EFV) — 5 percent

Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Small Cap Index ETF (VSS) — 9 percent

Special sector fund: 5 percent

Vanguard International Real Estate ETF (VNQI) — 5 percent

Taxable bonds: 10 percent

BNY Mellon Core Bond ETF (BKAG) — 5 percent

Vanguard Total International Bond Index ETF (BNDX) — 5 percent

Market-neutral fund: 4 percent

Merger Fund (MERFX) — 4 percent

Taking the safer road: Less oomph, less swing

We financial professional types hate to admit it, but no matter how much we tinker with our investment strategies, no matter how fancy our portfolio software, we can’t entirely remove the luck factor. When you invest in anything, there’s always a bit of a gamble involved. (Even when you decide not to invest, by, say, keeping all your money in cash, stuffed under the proverbial mattress, you’re gambling that inflation won’t eat it away or a house fire won’t consume it.) Thus, the best investment advice ever given probably comes from Kenny Rogers: You got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em.

The time to hold ’em is when you have just enough — when you’ve pretty much met, or have come close to meeting, your financial goals.

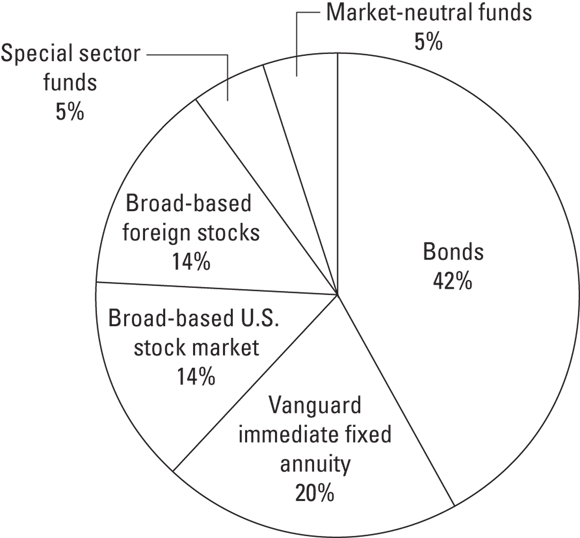

I now present Richard and Maria, who are just about the same age as Jay and Racquel. They are 64 and 59, married, and nearing retirement. Richard, who sank in his chair when I asked about his employment, told me that he was in a job he detests in the ever-changing (and not necessarily changing for the better) newspaper business. Maria was doing part-time public relations work. I added up Richard’s Social Security, a small pension from the newspaper, Maria’s part-time income, and income from their investments, and I told Richard that he didn’t have to stay at a job he hates. There was enough money for him to retire, provided the couple agreed to live somewhat frugally, and provided the investments — $700,000 — could keep up with inflation and not sag too badly in the next bear market.

I should add that the couple owned a home, completely paid for, worth approximately $400,000. They both agreed that they could downsize, if necessary.

For a couple like Richard and Maria, portfolio construction is a tricky matter. Go too conservative, and the couple may run out of money before they die. Go too aggressive, and the couple may run out of money tomorrow. It’s a delicate balancing act. In this case, I took Richard and Maria’s $700,000 and allocated 25 percent — $175,500 — to a Vanguard immediate fixed annuity. (The annuity was put in Richard’s name, with 50 percent survivorship benefit for Maria. It was agreed that should Richard die before Maria, she would sell the home, and buy or rent something more economical.) The rest of the money — $525,000 — I allocated to a broadly diversified portfolio largely constructed using ETFs. Figure 21-3 shows the portfolio breakdown.

FIGURE 21-3: A portfolio aimed at safety.

Broad-based U.S. stock market: 14 percent

Engine No. 1 Transform 500 ETF (VOTE) — 10 percent

Vanguard Small Cap Value ETF (VBR) — 4 percent

Broad-based foreign stocks: 14 percent

Vanguard Developed Markets Index ETF (VEA) — 10 percent

Vanguard Emerging Markets Index ETF (VWO) — 4 percent

Special sector fund: 5 percent

iShares Global Consumer Staples ETF (KXI) — 5 percent

Bonds: 42 percent

BNY Mellon Core Bond ETF (BKAG) — 12 percent

iShares Global Green Bonds ETF (BGRN) — 10 percent

Schwab US TIPS ETF (SCHP) — 10 percent

Vanguard Mortgage-Backed Securities ETF (VMBS) — 5 percent

iShares ESG Aware 1–5 Year USD Corporate Bond (SUSB) — 5 percent

Market-neutral fund: 5 percent

Merger Fund (MERFX) — 5 percent

Vanguard immediate fixed annuity: 20 percent

With 50 percent survivorship benefit

Please forget the dumb old rules about portfolio building and risk. How much risk you can or should take on depends on your wealth, your age, your income, your health, your financial responsibilities, your potential inheritances, and whether you’re the kind of person who tosses and turns over life’s upsets. If anyone gives you a pat formula — “Take your age, subtract it from 110, and that, dear friend, is how much you should have in stocks” — please take it with a grain of salt. Things aren’t nearly that simple. (Although if you’re going to go with any formula, the one I just provided is far better than most!)

Please forget the dumb old rules about portfolio building and risk. How much risk you can or should take on depends on your wealth, your age, your income, your health, your financial responsibilities, your potential inheritances, and whether you’re the kind of person who tosses and turns over life’s upsets. If anyone gives you a pat formula — “Take your age, subtract it from 110, and that, dear friend, is how much you should have in stocks” — please take it with a grain of salt. Things aren’t nearly that simple. (Although if you’re going to go with any formula, the one I just provided is far better than most!) If you are still far away from that 25 times mark, and you are not in debt, and your income is secure, and you are not burning out at work, and you have enough cash to live on for six months if you had to, then with the rest of your loot, you might tilt toward a riskier ETF portfolio (mostly stock ETFs). You need the return.

If you are still far away from that 25 times mark, and you are not in debt, and your income is secure, and you are not burning out at work, and you have enough cash to live on for six months if you had to, then with the rest of your loot, you might tilt toward a riskier ETF portfolio (mostly stock ETFs). You need the return. Please, please, don’t allow a computer-generated questionnaire to determine your financial future! I’ve tried many of them, and the answers can be wacky.

Please, please, don’t allow a computer-generated questionnaire to determine your financial future! I’ve tried many of them, and the answers can be wacky.