A story is the record of how some imaginary person copes with life.

(No, don’t tell me that stories may very well concern actual people. Any person in a story is fabricated. Though I write of Charlemagne or Catherine the Great or my 11-year-old daughter, I am none of these people, for I cannot get inside their skins. No matter how faithfully I record their actions, my interpretation of their dreams and thoughts and motives, their inner worlds, must of necessity remain my own. This being the case, these characters are in truth as imaginary as if I had created them from whole cloth.)

So: A story is the record of how some imaginary person copes with life. It satisfies a need in us by the way it gives a sense of form and order to our chaotic world.

A film story is a work of fiction, designed for presentation in motion picture form.

An effective film story is one that, when produced and released, pulls audiences into theaters. Often it achieves this feat in the face of competition that headlines bigger stars, a higher budget, greater “production values,” and more promotion.

The effective story does this by its use of desire and danger to manipulate tension in viewers. That is to say, it poises them for action, then relaxes them, according to a preplanned pattern. People attend films because they find this ebb and flow of tension stimulating and pleasurable.

How do you learn to manage these so-vital tensions?

A first step is to come to grips with precisely what constitutes desire and danger.

Desire is Humankind’s yearning for happiness, the one objective we all seek. But different things symbolize happiness to different people. One man dreams of eagerly wanton females. Another aches for the luxury wealth buys. A third pursues the power to make others fawn and grovel. And yes, you find desire at work in a suicide, too, or a misanthrope, or a failure.

Danger, in turn, is something, anything, which threatens our present or future happiness to the point where we’re forced to feel an unpleasant emotion: loneliness, loss, anger, inferiority, fear, hatred, or what have you.

Emotion is another name for inner tension; and tension is the driving force that powers all action.

Whatever fails to evoke emotion is worthless in any form of fiction. Anything that does involve a character, so deeply and disturbingly he’ll fight dragons to change the precipitating situation, will unfailingly involve viewers also. Why? Because the people, the mass audience, pay little heed to anything they view objectively. They want to be hooked on tension, drawn taut by feeling. They yearn to see a hero win, a villain lose: a human struggle against odds.

Thus, the drive of desire is the life’s blood of every film. And danger is its heartbeat.

“We go to the theatre to worry,” observed the late Kenneth Macgowan, outstanding Hollywood producer and long-time chairman of the University of Southern California’s Department of Theatre Arts. “Whether we see a tragedy, a serious drama, or a comedy, we enjoy it fully only if we are made to worry about the outcome of individual scenes and of the play as a whole.”

A writer’s plan of action for thus manipulating tension, evoking worry, is called a plot.

So, how do you plot a film story?

One of the easiest ways to start is with the old Hollywood springboard, “Who wants to do what, and why can’t he?” In other words, you pick someone who aches with desire. (No one else is worth a hoot, remember. Unless Character aches, he won’t strive; nor can he be defeated.) Another way of putting this is that when we say someone “aches with desire,” what we really mean is that Character wants to change something, and he wants it so desperately that he stands ready to take whatever action is necessary in order to make that change. Maybe, trapped in a low-pay job, he wants a raise so badly he’s willing to brace the boss for a raise even though it may get him fired. Or he applies for a job elsewhere. Or he sets about seducing Boss’s daughter so that Boss will see him as a prospective son-in-law and so be inclined to promote him. Or he devises a scheme to maneuver Boss into a situation so compromising that Management will replace Boss.

The list can go on endlessly. What counts is that Character sets his—or her—sights on change: Woman wants Married Man, so she seeks to change his status by somehow eliminating Wife. Impoverished Nephew wants to become Rich Heir—a change!—and if that means offing Aged Aunt, so be it. Priest’s dream is to win favor in God’s eyes by—change!—refurbishing his run-down church.

In each case, the trick is to commit Character to change. Then, threaten his hopes of attaining said change via dynamic opposition—a man or a task or a world that fights back.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, for a film story doesn’t spring into being full blown. Rather, it’s developed through a process of continuing elaboration, in a series of five phases: premise, outline/synopsis, treatment, step outline, and master scene script.

We’ll deal with it that way, then. In steps, phase by phase. Building from nothing to something.

Where do you start?

You begin by tracking down a premise.

FINDING THE PREMISE

A premise is the basic idea or concept behind a feature film.

It’s not an outline of the story itself, you understand; not even an explicit statement of the situation.

Indeed, it’s a most peculiar entity. All sorts of people get confused about it.

Why do they become thus confused? Mostly, because in the motion picture industry premise tends to be lumped with what I like to term a presentation.

Now a presentation is a sort of outline—a selling outline, as it were. If you try to include it with the premise, or attempt to pretend it’s the same thing, you end up with a mishmash that makes little sense to anybody.

Here, then, let us separate the two, disregarding any screams of outrage that may arise.

Also, let us reiterate the point we first made: A premise is the basic idea behind a film; the bedrock from which your story springs. It is not an outline.

Think of it, rather, as a hypothetical question—one that lays the foundation upon which your story situation is to be built. How does a solid premise come into being?

1. You find a topic that intrigues you.

2. You discover/develop a unique angle from which to view said topic.

3. You cast this idea within the framework of a hypothetical question.

Like the fact film, you see, the feature is undergirded by topic and point of view. The difference between them lies only in the way they focus.

In the feature, they combine to create a central “What if—?” question: the premise from which the feature’s story springs.

Do these events take place in neat 1-2-3 order: topic—angle—premise?

Well, hardly. Indeed, you often may find yourself with little control over how, when, or even if, they take form.

The situation is somewhat like that of a woman walking down the street. She remains just a woman—until someone, looking at her, suddenly sees her as a potential subject of seduction.

Similarly, a bank is just a bank, until someone views it as a potential source of loot, rather than a business institution. Or a wardrobe is just a piece of furniture until mental lightning strikes and, in some mind’s eye, it becomes a place to hide a body.

Now obviously this is nothing new. Your point of view is simply your subjective attitude towards a topic: the potentialities you see in it as foundation for a fictional situation. Its basis is your own heredity and conditioning, and no two people see any topic exactly the same.

The “good” topic is the one that stimulates your imagination to come forth with a “good” angle.

The “good” angle? It’s one that excites you, preoccupies you, sends your imagination soaring off on flight after flight of story-focused inspiration.

And yes, this is important. Tricks, techniques, mechanics, facility with language—all are vital to the scriptwriter. But they can never hope to substitute for the surge and drive born of your own very personal excitement.

But back to premise proper. Consider the picture of a few years ago, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Undergirding the plot lies one simple yet provocative thought: What if an upper class white woman fell in love with a black man?

That question is the story’s premise. It sets forth an idea that hooks your interest, needles your imagination. What you do with it, how you develop it, depends on your own taste and talent. You may produce a work of genius, or pure garbage, or copy at any level in between. But without the premise, you have nothing, even at the garbage level. Premise remains the writer’s firm foundation. All else is superstructure.

Consider the Disney hit, The Apple Dumpling Gang. Behind it, too, lies a simple premise: “What if a footloose gambler in the pioneer West suddenly found himself saddled with a brood of children?” That delightfully offbeat picture, The Gods Must be Crazy, takes off from “What if a Coke bottle dropped from an airplane were to totally disrupt life in a primitive African tribe?” Space Camp springs from “What if an accident during a routine engine check sends a diverse group of teenagers into orbit?”

Or, suppose we here devise a premise of our very own.

Let’s begin with a topic: in this case an object, a Brinks-type armored truck.

Why an armored truck? Because a few years ago I reviewed a top-notch suspense novel, The Kidnapping of The President, by Charles Templeton. The author made excellent—and unique—use of an armored truck in his story. Couple that with another intriguing volume from my shelf, John A. Minnery’s The Trapping and Destruction of Executive Armored Cars, and I found myself preoccupied with the challenge of finding a different yet interest-hooking point of view on armored trucks to play with. What shall it be? Robbery? A hiding place? A mobile fort? Some sort of red herring?

Well, robbery’s out, of course; too commonplace. And neither the hiding place nor mobile fort bits strike any sparks in my imagination. As for the red herring gimmick …

But wait—! Suppose we use robbery, after all, only the robbery’s not really a robbery, but a cover-up, a red herring! Maybe, for instance, someone wants to conceal an embezzlement with a fake robbery. Or to distract attention from a bank heist with a noisy, flamboyant attack on an armored truck. Or to launder hot Mafia money by switching it for the truck’s load—

Hey, that’s it! A switch! But not the Mafia thing; that’s old hat and besides, if Mafia types are going to the trouble of knocking off an armored truck, they’re going to hang onto all the money, not just part.

No, we need something much more human; much less routine. But we’ll find that, given a little time. Meanwhile, what’s important is that we’ve found our angle—an angle we can frame neatly in an appropriate, intriguing “What if—?” question: What if someone robbed an armored truck just in order to switch hot money for that aboard the vehicle?

The important thing about working from a premise thus is that it forces you to razor-sharp awareness of your story’s basic concept.

Every story has such a core idea, you see. The only issue is, is said idea strong or weak? Unless you zero in on it, in its simplest, starkest form, you may discover too late that it holds fatal flaws that point you straight down the track to disaster before you ever set a line on paper.

Given a clear, incisive premise, on the other hand, your story is stripped of many of the ills that might otherwise beset it. In writing, you’re able to avoid the extraneous … shear away fuzziness and sharpen focus. You present a concise, tightly organized product, geared to maximum impact and effectiveness.

Producers and story editors like that kind of work. They find a place in their hearts and checkbooks for the writer who writes it.

How do you create a solid premise?

1. As already described, you frame the basic idea of your story, the concept on which it rests, in terms of a “What if—?” question.

2. You check this question for

a. Freshness.

b. Relevance.

c. Dramatic implications.

d. Practicality.

3. You sharpen and strengthen the idea at any point where weakness becomes apparent.

Point 1 is, I trust, already clear. But what about point 2a, and freshness?

Your goal, in premise, is to catch attention, arouse interest. The trite or familiar just won’t do this. Clichés in speech constitute a reasonably apt parallel: The first time you heard someone speak of something as “smooth as glass” or “cold as ice” or “sharp as a knife,” it probably caught your ear … created a vivid image in your mind.

Today, as we observed in our chapter on narration, those same phrases no longer touch you. Overuse has worn away the edge of each to where you’re hardly aware the words are spoken.

It’s the same with stories. Freshness, the unique twist, stands all-important. Tell someone your tale concerns boy meets girl and his mind switches off—until you add, “and the girl is a Siamese twin!” A story set in a florist’s shop seems too routine to hold interest on the screen. But, if the prize plant eats people—well, remember Little Shop of Horrors?

It’s also worth bearing in mind that ideas often come from the most unlikely places and by the least likely routes. That hilariously refreshing comedy, Ruthless People, offers a case in point. It’s about a couple who abduct a woman who’s such a harridan that her husband doesn’t want her back. When he stalls on paying for her release, it enrages her so much that she joins forces with her kidnappers.

I took it for granted scriptwriter Dale Launer’s inspiration had been the old O. Henry short story, “The Ransom of Red Chief,” in which a super-brat seized by an inept pair of crooks drives them up the wall. But when I talked to Launer, I learned that I was wrong. Although he was familiar with “Red Chief,” his springboard to Ruthless People actually had been Patty Hearst’s kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army terrorists.

“They asked for a big ransom. When they didn’t get it, they somehow convinced her that her parents didn’t want her back,” he explained. “They did such a good job that she joined them, and I thought that was actually kind of funny.”

Relevance? That’s simply another way of saying your story must make emotional sense to your viewers. To that end, it needs to catch them up in the kind of feelings they themselves have felt and so understand, all projected in terms pertinent to life today. Thus, the success of Under Fire and Silkwood lay in their use of color and today’s political realities to evoke fears that lurk in all of us; recent Vietnam pictures offer such disturbing insights and conjectures regarding that bloody conflict as to rouse fears, and so become relevant to us. Half Moon Street portrays a liberated, highly educated, politically sophisticated woman turning to prostitution to increase her income.

For a premise to have dramatic implications, in turn, means that it must show the possibility of plunging people into conflict. Preferably, this conflict should be visible and involve other people. For while the story rooted in a monk’s inner struggle as he kneels in his cell will fascinate a certain number of viewers, far more will be caught up in clashes that match man against man. (Or against woman—conflict exists wherever will battles will, of course, and this holds as true in a seduction as in a fist-fight.)

Practicality becomes an issue on two levels: First, technical difficulties involved in filming can stop a project cold. A premise of “What if the world came to an end and our hero alone, surviving, had to reassemble Earth from atoms?” involves complications few producers would care to tackle.

Level Two is cost. If you’re trying to connect with a shoestring independent who lacks even set rent, it seems unlikely he’ll be interested in a script based on the premise, “What if Napoleon, rising from the dead, led France’s legions through a new conquest of Europe?”

On to point 3: Is it easy to sharpen and strengthen a premise?

Here the answer is, “Sometimes yes, sometimes no.” Despite your best efforts, on occasion, your premise will remain tired and trite. You’ll find yourself unable to give it appeal to a sufficiently wide audience. Or you’ll recognize intuitively that the public will feel it irrelevant or view the conflicts it offers as too shallow or trivial. Or you’ll be forced to acknowledge that practical problems or costs will simply prove too great to warrant producer interest.

When such happens, the answer is to move on to another, stronger project, rather than to waste time and energy beating the dead horse of an idea gone sour.

But more often than not, things will fall into place far better than you anticipated. The secret of success is to use the principles we dipped into in Chapter 1, in discussing how to make the most of your creative powers. Get in there and juggle pieces! Inject new elements! Work till you hit a combination that captures your own imagination! A couple of young fellows traveling cross-country by cycle is mildly intriguing—who hasn’t had a yen to do so? But make the pair hippies and you add whole new dimensions of freshness and relevance and conflict. A producer seeking a hit is old hat; one striving to fail comes off as new, different, funny.

So keep analyzing; keep rearranging; keep striving. Even though your first efforts seem incredibly clumsy, totally fruitless, the very effort of trying to set up a clear, sharp premise can’t help but whet your own skills at thinking and at writing. And such keen-edged tools are a first step towards success in this scripting business, believe me!

Bear in mind, however, that not every idea, not every premise which you develop, is going to strike sparks in others also. A good many times, you’ll discover someone else has already made use of the same concept, as I did once some years ago when Jack Emanuel at Warner Brothers blasted one of my pet ideas by citing chapter and verse of at least three times it had been used previously.

In other instances, prior producer/director/actor commitments, technical difficulties, financial involvements, or just plain ineptitude on your own part will shoot you down. You’ll find you’re lucky indeed if you hit with one “What if—?” out of five or ten.

Further, a gleam of interest in regard to the presentation you build from a given premise is no assurance said interest will continue. Quite possibly you’ll be cut off at the next stage, or the next. I still can bleed when I think back. …

But that’s enough on the negative side. Right now, let’s assume you’ve found a truly satisfying premise.

Next question: What do you do with it? Whom do you show it to?

If you take my advice, in all likelihood you won’t show it to anyone. Why not? Because a premise, in and of itself, is a poor calling card.

Instead of charging off in all directions the moment you come up with a premise, therefore, consider your idea as a seed only—a seed which may or may not sprout. You, because you know it so well, can already envision the lovely plant which—potentially—will spring from it.

It’s unlikely, however, that anyone else will be able to appreciate it fully. So it follows that it’s wisest not to show your treasure around at this stage. Rather, be patient. Cultivate and nurture your prize in private. Work on it till you have it developed into a fuller form; one more likely to excite others.

This form is one that goes by many names—synopsis, outline, story line, synopsized theme. The term I prefer, the one we’ll use here, is the presentation.

PREPARING THE PRESENTATION

A presentation is a sort of sales-pitch for a premise. Indeed, scriptwriters ordinarily use the term pitch when they speak of making a presentation.

The purpose of a pitch, a presentation, is to hook a producer’s attention. It’s designed to give you a chance to set forth your basic idea. You can do this with a hook, a gimmick, a character, a scene, or the abovementioned basic idea itself. If you catch the interest of producer or story editor or whomever, you then can sketch in your story’s broadest outlines—and do so in such terms as to develop the contact further.

What persuades a producer to o.k. an idea?

First, a belief that the premise itself has strong audience appeal.

Second, a demonstration of the premise’s dramatic potential.

How do you give such a demonstration? Every writer has his own system—and every one of them that works is right.

You, too, eventually will develop private notions on the subject. Meanwhile, however, it may help to have some sort of rule-of-thumb procedure to fall back on while your own ideas are jelling.

Remember what we said about desire and danger, back in our section on the film story? About the necessity of building our attack around a someone who wants something desperately, but whose chances of getting it are somehow jeopardized?

Well, there are worse places than that to start, when you set about laying out your project.

It will also improve the odds, I suspect, if you’ll plan your epic work in terms of an old-fashioned, Aristotelian beginning, middle, and end.

Above all, you’ll chalk up brownie points if you work from a thing I call a starting lineup. For while many will snort, and while it certainly isn’t the only approach to building a story, it does offer a simple, practical procedure for the beginner to use as springboard.

The lineup is a sort of checklist designed to focus story elements into a pattern which allows appraisal of their dramatic potential. To that end, it zeroes in on five factors:

1. A character.

The central character in your story, that is.

Actually, a character isn’t just a person; he—or she—is a point of view. An individual with a strong attitude towards your topic, he’s someone you can involve in the “What if—?” of your premise with full faith that he’ll react.

2. A predicament.

A predicament is a premise-related state of affairs somehow sufficiently uncomfortable as to arouse emotion—that is, tension—in Character; and so, hopefully, to arouse emotion and create tension in viewers also. The issue is empathy, as we observed in Chapter 3.

An objective is a prize for Character to fight for …a new and different state of affairs, happier than that revealed in Predicament, which Character hopes to attain.

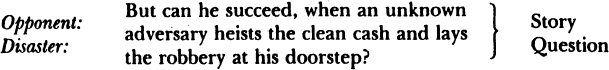

4. An opponent.

An opponent is someone or something for Character to fight against. He, like Character, is a point of view—but one in such contrast to that of Character as to insure conflict within the situational framework arising from the premise.

5. A disaster.

A disaster, as I use the word here, is the potential terrible fate with which you confront Character at climax as his penalty should he lose. It also provides the ultimate focal point for audience tension.

So much for the ingredients of our lineup. Obviously, they’re designed to provide broad outlines only. But don’t worry about holes; we’ll plug them later.

Next step: Group the five ingredients into two sentences—the first a statement, the second a question.

Sentence 1: A statement of story situation in terms of character, predicament, objective.

Sentence 2: A “will or won’t Character succeed?” story question, compounded of Sentence 1 ingredients plus opponent and disaster, and all designed to keep your viewers panting with excitement.

Together, these two sentences will go a long way towards keeping your script soundly structured, on the one hand, yet tautly gripping, on the other. For the pattern they provide does work.

Let’s take the sample premise we built earlier … develop it as a case in point.

Remember the premise? “What if someone robbed an armored truck just in order to switch hot money for that aboard the vehicle?” Where do we begin, in turning this into a starting lineup?

Well, why not start with the “someone”? Arbitrarily, we’ll assign him the name of Earl Parrish. Age 30, in order to appeal to a young audience. And since robbing an armored truck may prove on the strenuous side and call for appropriate skill with weapons, we’ll make him a former Marine, survivor of the disastrous 1983 barracks bombing in Lebanon. After all, if any part of this doesn’t work, we can always change it later.

Next question: Why has Earl decided to go into the armed robbery business? Is he vengeful, money-hungry, criminal psychopath, or what?

Somehow, none of those angles turn me on. For even though I’ve barely met Earl, I find myself liking him. I doubt he’s just a common thug.

So what would turn a non-thug to robbery? Duty? Blackmail? Altruism?

Duty, in these circumstances, strikes me as a little too James Bondish. Blackmail? Well, maybe. Altruism? Hmm …

Then, while I brood, the right word comes. It’s loyalty, a trait admirable in and of itself, yet in whose name all sorts of crimes have been committed.

Shall we try it for size? To whom or what is Earl loyal? A relative? A friend? A sweetheart? A Service buddy?

But no. All such are too routine, too predictable. Let’s reach farther out … try to find some figure who’ll give our plot-to-be a logical yet unanticipated twist.

Like one of Earl’s former school teachers, for instance.

And there we have it—we hope: One of Earl’s old school teachers is in trouble. Maybe, for an added touch, she doesn’t even know it. Innocently enough, she’s bumbled into a situation where she’s in possession of a suitcase full of demonstrably stolen money. The only way to get her off the hook is to switch the hot cash for cold. One thing leads to another, and the next thing Earl knows, he’s committed to making the exchange via an armored truck robbery.

Fine! But that’s only the first unit of our lineup, the statement of the story situation. Now, what about the second, the vital, suspense-building story question?

Well, for one thing, we need an opponent, an adversary for Earl to battle. Not to mention a disaster, a startling—and devastating—twist around which to build our climax.

For now, let’s take the easy road where Opponent is concerned: We’ll keep his identity a secret from Earl.

As for the disaster, there’s an old rule of thumb about such that says make it the most appalling thing that can possibly happen.

What might that be, in Earl’s situation?

A possibility: Earl robs the truck, gets the clean cash—and then Villain not only steals it from him, but frames him for the theft!

Here are how these points look, set up within the framework of a starting lineup:

Please note that the lineup offers basic story elements only. Starkly skeletal, it makes no pretext of revealing the entire picture. Like the premise, it’s more a writer’s working tool than something to pass on to others. Its greatest value is that it forces you to think in fundamentals. Yet because it lays out a dynamic plan of action, certain elements to look for and decide on, it blasts you off dead center. Do learn to use it!

Clearly, this kind of thing takes practice. Go see three or four or five feature films, entertainment movies. Then, write out a two-sentence starting lineup for each, as outlined above.

Once you begin to get the knack, frame up potential film stories of your own. To acquire facility, work out one each night before you go to bed. You won’t believe how much you’ll improve in a month. Besides, it’s not that much work … only two little sentences per night… just the kind of preparation you need for your next step, the sketching in of

BEGINNING, MIDDLE, END

Lay out a story based on one of your starting lineups in whatever manner best suits your tastes. Then, break it down into beginning, middle, end. Develop each in a paragraph or two, not more—the idea, remember, is to frame up broad outlines only.

The beginning establishes your character within the framework of his predicament, nails down his objective, and carries the story forward to that point where Character commits himself to fight to the bitter end to attain his desire.

The middle reveals the various steps of Character’s struggle to defeat the danger which threatens him. And if you want your viewers to sit through it, you’d better cram it with fresh ideas, intriguing twists, and intensity of feeling.

The end sees Character win or lose his battle. Remember, in this regard, the story doesn’t truly end until the struggle between desire and danger is resolved, with some kind of clear-cut triumph of desire over danger, or vice versa.

Applying this breakdown to our money truck caper story, we might end up with something like this:

Beginning: What if someone robbed an armored money truck just in order to switch hot money for that aboard the vehicle? This is the situation we confront in this different caper story.

Our setting is Appalachian Chicago—the decaying Uptown neighborhoods along Kenmore, Wilson, Argyle … our central figure, 30-year-old Marine vet Earl Parrish, currently footloose but in all likelihood en route to a mercenary’s job training troops in Latin America. Now he learns that the safety deposit box of a dying hillbilly schoolteacher who helped shape his life when he was a boy back in West Virginia contains $60,000 in sequentially numbered bills, hot currency from a bank robbery. If the authorities discover it, it will not only destroy Teacher, but put an end to her dream of a small private program to help disadvantaged hill country kids from her home county.

At present, Teacher knows nothing of all this. It’s unthinkable that she could be involved. So the only way out is to switch the stolen money for clean bills. To that end, and despite the fact he’s an ex-deputy sheriff, Earl agrees to head up the robbery of an armored truck.

Middle: Gathering together a weird assortment of Teacher’s other ex-pupils to help him, Earl plans and carries out the switch … halting the truck by spray-painting all windows, forcing crew to open it by pumping tear-gas through the ventilating system, etc. His task is made immeasurably more difficult by the divergent personalities and motives of his aides.

End: The time to put the switched cash into Teacher’s safe deposit box arrives. Only now Earl discovers that the money’s missing; the only likely suspect, dead. But the very fact of Suspect’s death clears all members of the heist group … lays guilt in the lap of an exhillbilly minor bank official who had access to Teacher’s box.

When Earl goes to confront Official, he himself is trapped. Though he kills the bank man and recovers the cash, he now has no way to get it back into Teacher’s box. The cops are hot on his trail, too. He has no choice but to run. His girl, a social worker who first discovered the hot money in Teacher’s box and then conceived the robbery scheme, asks to go along. Earl refuses; he must take the mercenary job. Her assignment, in turn, is to deliver the suitcase of cash to a small-town West Virginia bank. Banker, Earl’s friend, will see that it’s used to carry out Teacher’s plan.

Earl leaves. Girl watches him go … sets off down street with suitcase… pauses to greet a pre-planted Mexican or Puerto Rican vendor: “Buenas noches, Ramon.” And then: “Tell me, amigo, how long will it take me to learn Spanish?”

Note, please that our story is growing as we go along. Just as premise expanded into lineup, so lineup now has been fleshed out into a more coherent story.

This is as it should be. If there is one principle that underlies every form of writing—and, especially, of film scriptwriting—it’s this concept of continuing elaboration, building from seed idea through step after step to finished form.

Thus, Earl Parrish is taking on stature almost by the minute … becoming less a name and more a person, complete with past and future as well as present. “Plus” elements—colorful people, striking settings, unusual scenes, unique mood material, and the like—also are beginning to appear: Note the incorporation of the “Appalachian Chicago” background; the assembling of transplanted hillbillies to pull a metropolitan caper; the halting of the armored truck by spray-painting the windows, and so on.

These bits are still in embryonic form, of course; only just beginning to develop. But that’s all right. It takes time to build a solid film script.

Finally, there’s the matter of a working title. Make it as intriguing as you can, naturally. But even a bad title is better than none at all. It at least gives people some sort of label by which to designate your opus.

What shall we call Earl Parrish’s saga? Tentatively—and with apologies to all concerned with that thrill-packed epic, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three—let’s title it The Heisting of Money Truck Four Five Six.

HOW ABOUT FORMAT?

As you’ll see from the sample that follows, and those in Chapter 18, there are few rules as to how to set up a presentation. Striking content, plus enthusiastic dramatization, are what count. Just be sure to include—in whatever form or order—premise, starting lineup elements, beginning-middle-end, “plus” factors, and title, and you’re not likely to go too far wrong.

Film Outline

The Heistinq of

M O N E Y T R U C K 4 5 6

(Tentative Title)

Earl Parrish is a man cool and tough enough to rob an armored money truck, but he has principles. Indeed, it’s precisely because he has principles—especially a sense of loyalty—that he agrees to stage the robbery.

Our setting is Appalachian Chicago—the decaying neighborhoods along Kenmore and Wilson and Argyle. Thirty-year-old Earl, our central character, is the coolly dangerous product of a West Virginia mining county, an ex-Marine now jobless and footloose like thousands of other veterans, Chicago is a last fling for him before he signs on as a mercenary to train troops in Latin America.

Quite possibly we first meet Earl as he tramps purposefully along a drab Chicago street. Then an armored money truck pulls up across the walk and blocks him off. Guards get out and take posts while money is loaded or unloaded. Earl scowls at the car. We follow his glance, zoom in to a frame-filling closeup of its number, 4–5–6, and then cut back as titles come on over.

Earl has a problem. One of the most important people in his life has been a hillbilly schoolteacher who helped shape him when he was a boy back in West Virginia. Mow that teacher lies dying here in Chicago. Her life savings of $60,000, which she wants to see devoted to helping disadvantaged hill country kids from her home county, are in a safe deposit box in a neighborhood bank. The only catch is that a girl social worker has discovered that said savings have been replaced with sequentially numbered bills, hot currency from a bank robbery. If the authorities discover it. Teacher’s dream will be shattered, her heart broken, and her good name besmirched. The only way out, as Girl sees it, is somehow to switch the stolen money for clean bills. To that end, she wants Earl to direct the robbery of an armored money truck.

Loyalty to Teacher overrides good sense, for Earl. He agrees…recruits a weird assortment of other ex-pupils of Teacher now in Chicago.

Planning and carrying out the robbery is made immeasurably more difficult by the divergent personalities and motives of these aides. But Earl finally succeeds in bringing off the heist by spray-painting the truck’s windows so it has to stop, then pumping tear-gas through the ventilating system to force the crew to open the doors.

When the time comes to put the clean cash into Teacher’s safe deposit box arrives, however, Earl finds the armored truck money is missing; the only likely suspect in the theft dead. But the very fact of Suspect’s death clears all members of the heist group…lays guilt in the lap of an ex-hillbilly minor bank official who had access to Teacher’s box. Confronting him, Earl himself is trapped. But though he survives to kill the bank man and recover the cash, he now has no way to get it back into Teacher’s box. The cops are hot on his trail, too. He has no choice but to run.

First, though, he takes the money to the social worker. Unhappily, she reveals that it makes no difference now, for in the interim, Teacher has died. As for Earl’s running, she wants to go along.

Earl refuses; he’s off to take the mercenary job. Girl’s assignment, in turn, is to deliver the suitcase of cash to a hill-country West Virginia bank. Banker, Earl’s friend, will see that it’s used to carry out Teacher’s plan.

Earl leaves. Girl watches him go…herself sets off down the street with the suitcase…pauses to greet a pre-planted Mexican or Puerto Rican vendor: “Buenas noches, Ramon.” And then: “Tell me, amigo, how long will it take a girl like me to learn Spanish?”

THE END

A final question: What about the validity of the pattern I’ve oudined?

Have no illusions. Jean-Luc Godard won’t approve, and neither will Jonas Mekas. But the approach does work—most successful feature films fit in—and it is the pattern of life … which is to say, the pattern of People with Problems. You can see this even in your own conversation: “Mrs. May left for church at 10:15 today” interests no one. “Mrs. May left for church at 10:15 today—and no one’s seen her since,” captures instant attention.

This isn’t to say that chronological order is always the best way to present your material. Quite possibly you’ll find good reasons to depart such in order to start from some more dramatic or more mood-inspiring or more emotionally meaningful moment. The issue is simply to think through basic story first, then pick the most effective way to present it.

Also, in any particular picture, story may be subordinated to other elements. Thus, fantasy dominated in Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo … violence and special effects in Aliens … sex and horror in The Fly.

So it is with your presentation. Its goal is simply to cast whatever raw material you choose to use into some sort of interest-catching form, with a central character set up to move in a particular direction. Then, because the human animal likes life to show at least a semblance of meaning, order, you make sure to include an ending that rounds things out by postulating the victory or defeat of Character in his efforts.

Observe how free this approach leaves you. Though I’ve here developed Money Truck 456 as straight melodrama, it could equally well be shaped for dramatic comedy on the Tough Guys order, or Prizzi’s Honor brand tragedy, or almost anything else you might choose.

* * *

So much for the film story. Now, let’s take a closer look at its most vital ingredient: the film character.