Stress Testing and Risk Management

Stuart Burns

Standard Chartered Bank

What Is Stress Testing?

The term “stress testing” can mean something different depending on who is using it and in what context. In this chapter, some observations about the current status of stress testing in financial institutions and the possible ways forward from this will be discussed. First, however, the approaches to stress testing and scenario planning commonly in use are outlined.

A “scenario plan/analysis” typically looks at an event or scenario and uses expert judgment to develop possible impacts from this. Hence, if the scenario is an outbreak of avian flu transmitting to humans, we would typically think about what the economic and people effects are likely to be on a global basis. We would then focus on our own portfolio, staff, and customers and consider the potential effects on our own financial institution. These would include both losses due to unfavorable events and the possible reduction in revenue within this environment.

Stress Testing and Operational Risk

A number of these effects may lead to undesirable outcomes, for example, our staff not being able to work as the site of the bank’s operations has been quarantined. Typically, we would develop some contingency plans around this (such as the use of a back-up or disaster recovery site). In most cases, the contingency plans are already in place through the development of disciplines such as business continuity planning and hence we are effectively stress testing the contingency planning by walking through a plausible scenario and understanding its impact upon our business. Where this exercise highlights that the existing contingency planning is unable to provide an acceptable level of mitigation to the risk identified, then we would look at the likelihood and level of impact under the existing risk plans.

This is commonly known as “heat mapping”—an illustration of this being given in Exhibit 4.1. An assessment can then be made as to the potential and plausible outcomes where we need to revise our contingency planning. This would be based on our not being comfortable with the likelihood of the risk crystallizing, or the impact if it does, or a combination of both measures.

Exhibit 4.1 Conducting the scenario analysis

Source: Author’s own.

If we can quantify the measures of likelihood and severity, we can then take the product of these for an “expected loss” style approach to prioritization. An alternative qualitative approach which has been seen to work well is to use the dimensions of impact and level of control/mitigation—the idea here being we focus on high-impact risks we can actually control. An unfortunate by-product of this approach is the potential identification of risks of high impact that we cannot easily control or mitigate—where these are identified it probably results in sleepless nights for the risk manager concerned.

Both approaches are two-dimensional, which lends them well to graphical representation. Practically, anything more complicated may become difficult to interpret, but the ideal metric for prioritizing risks probably includes at least likelihood, severity, reputational impact, level of control/mitigation, and time horizon.

Stress Testing and Credit Risk

The scenario plan/analysis approach lends itself very well to operational risks, where there are many possible causes and typically we cannot use a model-driven approach to evaluate impacts or mitigation. Indeed stress testing, or the taking of a single risk from a continuum to an extreme value, is currently rarely undertaken in operational risk areas.

The scenario analysis style of approach, however, can also be applied to credit risk. In this area, we would typically be able to be more quantitative in our approach, as we have numbers available relating to exposures, limits and, hopefully, probabilities of default all driven off external ratings or internal models. The exercise in its simplest form would proceed as mentioned earlier, though expert judgment would be used to predict the global impacts of the event in question and then these impacts would be considered from the perspective of their influence on the bank.

It is possible that a little more mathematics would be used here, as compared to the previous example. For example, if the event is (as mentioned earlier) an outbreak of avian flu transmitting to humans, we may use expert judgment (typically involving an economist as well as colleagues in credit risk) to predict the impact on a number of macroeconomic factors, such as employment rate, exchange and interest rates, property price indices, and so on. It is worth noting that a shift in one of these macroeconomic variables will typically produce a twist in the risk variables.

Stress testing for credit risk is rather different in its approach and its objectives. Currently, firms typically look at the impact of a single credit rating downgrade across the entire credit portfolio, with the ultimate stress being perhaps two credit downgrades right across the risk spectrum. This is really not a very realistic approach to stress testing and, while it does produce some interesting information, it is difficult to really interpret. At its most basic level, things do not really go wrong like that, so a one credit rating drop for all credits is really not a plausible scenario.

Another approach would be to consider the impact of a single variable upon the overall book of credits. Here you would isolate a single variable and then apply the stress event to that variable.

If you were, for example, to stress employment rate in a retail portfolio this would typically have a much greater effect on the probability of default (PD) for lower credit grades than for the better credits in the portfolio.

Consider the case, however, of wholesale portfolio, premium goods manufacturers. These firms would potentially be insulated against changes in this employment rate when compared to those manufacturers whose products are goods pitched at a section of the population more susceptible to changes in the employment rate.

If, for example, a firm were to adopt the property price index as an input factor in one of the credit models for a risk variable such as loss-given default (LGD), then the various measures of risk for which the input is used should also be considered in this exercise. You would typically consider the effect on expected loss, which would result in increased provisions, and also the effects on capital requirements. This would include reviewing the impact upon both the regulatory minimum under Basel II, Pillar 1, and an internal estimate of this through an economic capital model (this being a typical approach for Pillar 2 of Basel II). As we move toward this more quantitative approach, where we drive various risk measures according to the stresses in the underlying variables, our approach becomes more one of “stress testing” than a classic scenario plan.

While both expert judgment and models have their place, ideally both should be used wherever possible to give robust estimates of the impacts and effects of mitigation. This way, we have expert engagement and buy-in, without purely relying on models, but also (and, in my view, as importantly) we have robust quantification of risks without relying blindly on expert judgment, which is as big an error as relying blindly on models.

Preventable Disasters

Brian Toft at the London School of Economics recently described how preventable disasters happen through human interaction. One important and well-known mechanism in this is “groupthink,” where the committee responsible for assessing risk ceases to be a number of independent thinkers and instead becomes a single operating unit with limited scope for innovation. This typically occurs when there is some form of pressure (real or perceived) to conform to the “party line” regarding assessment of risks. There is probably a potential groupthink around models as well, though it is suspected this is less overtly political.

The solution to this problem is similar in both instances, namely to ensure that there is a robust challenge process and that there is no pressure to conform. Debate should be encouraged rather than stifled and the importance of the culture around risk in an organization cannot be overemphasized. This can also serve as a note of caution when undertaking stress testing. If everyone agrees with your model assumptions or expert judgment, then this may not be a sign of the validity of these assumptions, rather it might be a measure of the political pressure you have been under to conform! It does not follow that when there is a robust debate about every risk assessment that the assumptions used in that risk assessment are sound; but it does at least prove to us that groupthink is not occurring.

It is also clear, however, that management do need to buy in to the assumptions and expert judgments that are required in both stress testing and scenario analysis. If they either fail to do so or fail to understand the implication of these assumptions, then the process of consequent management decisions will certainly be flawed.

Stress Testing and Market Risk

Within market risk, the approach adopted by firms is likely to be more quantitative still, given the availability of data on the effects of various events on market prices and liquidity. Typically, the event-driven stress test in market risk would go from the consideration of a hypothetical event to then consider the effects on macroeconomic variables. The effects on market prices and hence on the measures of market risk (such as value-at-risk) can then be quantified.

In practice, firms still tend to look at the impact of a single variable on market risk; perhaps a change in interest rates or the movement of an exchange rate or index. Sensitivity analysis takes this single variable and changes it by a unitary amount, evaluating the impact on the total portfolio of such a movement. The stress test will be to take this to an extreme value. Again, the extreme value should be a plausible one and is often based on events that have occurred in practice.

If you look at events in history, they may provide a firm with an insight into what could potentially occur in the future. Of course, the past can never predict the future with certainty, so even then a level of management judgment is still necessary. In practice, events such as Black Monday, the impact of the failure of Long Term Capital Management on the financial sector, and the impact of the default of the Russian rouble are the most commonly used stress events.

More use of the expert judgment approach is likely to be required if we look at the effects on liquidity risk. In the case of a retail bank, this can be of even greater complexity as you are trying to capture in a stress test the impacts of human behavior on an extreme situation. If interest rates reduce by 25 percent, what will this mean to your customers? A classical stress test would purely calculate the impact of the 25 percent reduction across the entire portfolio of positions held by the bank. If customers choose to withdraw a greater amount of funds than classically anticipated, however, the assessment conducted will be fatally flawed.

Risk Correlation

Basel II and the use of capital as a common currency for risk places additional demands on linking across risk types. This is especially the case when one looks at an event-driven scenario, such as the avian flu epidemic mentioned previously, or some geopolitical disturbance. While we are talking about an event and its impacts in qualitative terms, it is relatively easy for the various risk types to be married up, but as soon as we want to look at a quantitative impact (how much capital do we need across all risk types for this event) then we begin to struggle.

In fact, most banks undertake their stress tests by risk silo—effectively separately calculating stress events for each of the various risk types (with few, if any, conducted to address operational risk). This is partly due to the inconsistencies in modeling approaches between the differing risk types and partly due to the complexity and cost of undertaking multiple stress tests.

The advent of Basel II has certainly done a lot to bring stress testing into the consciousness of senior management, with all the exhortations around their oversight of the stress-testing process. The regulatory output has been informative in categorizing a number of varieties of stress test/scenario analysis.

“Sensitivity analysis” is defined as a single-factor stress test. By implication, this is quantitative in nature and typically would not reference an event so much as a unitary movement in a single risk factor, such as exchange rates or commodity prices. Typically, we should incorporate some time dimension into the analysis, so that our future plans and the shock and potential recovery from this are quantified over time.

Some commentators define sensitivity analysis as evaluating the “delta” with respect to a particular risk driver and assuming that changes in a risk driver are small enough such that you can assume linearity in the effects of these changes. For example, if you know the effect of a one basis point increase in a particular interest rate on value-at-risk, under these assumptions a two basis point increase would produce double this effect. However, many instruments are nonlinear in their sensitivity to such movements and this approach will become increasingly more questionable if we are testing for larger movements in the risk drivers.

The above is to be contrasted with scenario analysis (or multi-factor stress testing), where multiple risk factors are combined. This will typically be as a result of a scenario, either historical or hypothetical, such as the avian flu example given earlier.

The selection of factor/event should be based on key concerns of senior management, such as profitability, market value, reputation, and so on. These may be informed by identified control weaknesses. This would, however, require independent thinking around the control environment as described earlier, or some lucky “near miss” to have actually occurred in practice to inform our thinking. For example, if we have a situation where legal documentation is shown to be inadequate but we make a full recovery, we should use this as a scenario to check the adequacy of our documentation elsewhere. Equally (and increasingly), regulators will ask for a scenario or stress tests to be conducted to address and answer their justifiable concerns regarding a perceived risk to the financial sector. Obviously, it is better for a bank to take a proactive view and have something prepared in advance rather than be pushed into action by the regulator. What is clearly required is a structured and complete set of sensitivity, stress and scenario tests that are conducted on a pre-agreed and prescribed basis, as agreed with management.

An event-driven scenario analysis should typically consider multiple risk types. In practice, however, this is rarely fully undertaken due to the cost and complexity of doing so. Where economic conditions deteriorate there are likely to be effects on both credit and market risk.

Most banks are still developing their approach to operational risk to such a level that it will facilitate a higher level of analysis. Where our approach to operational risk is sufficiently sophisticated, our intention is to design a series of appropriate sensitivity and stress tests. For example, these might address the increased incidence of fraud in an economic downturn, or the impact on our business of a significant increase in processing volumes.

The Reverse Stress Test

As well as concerns around history repeating itself or hypothetical events becoming reality, you may also want to do what is termed a “reverse stress test.” This is where you start with a risk indicator, such as economic capital. For any risk indicator, management should have defined a suitable level of acceptability that is consistent with your risk appetite.

You can start the reverse stress test by assuming that this risk appetite is breached, that is, that the indicator goes beyond acceptable levels. For this to occur the variables that are effectively inputs to this risk indicator must have risen to certain levels and from this analysis you can then look at what would cause this to happen and how likely this may be. This is to be recommended as a very robust way of managing risk, provided one has confidence in the model assumptions, because it avoids taking “flavor of the month” (i.e., whatever is on the front page of the financial newspaper of choice) scenarios and actually looks at what would be a threat to the firm’s operations.

Ideally, stress testing should be integrated into a number of the bank’s activities under Basel II. The effect on capital requirements has already been mentioned and this will also impact on budgeting and the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP) under Basel II, but, actually, anywhere where you have a model for managing risk, sensitivity analysis, stress testing, and scenario analysis can provide an alternative view as to the accuracy of its outputs.

Stress and scenario testing should also be both “top down” and “bottom up.” This means that you should consider both the concerns of senior management at a group level and local concerns in country, business or risk type and how these might affect the whole group.

The Standard Chartered Structure

In a talk entitled “Stress—And How To Cope With It,” I outlined many of the issues in dealing with stress testing in the current Basel context, based on my experience at a bank that operates in more than 50 countries and is answerable to a range of regulators. This level of complexity is not unique. It does make for additional stress, however (using the term in common parlance), in terms of trying to coordinate across the piece.

Clearly, as with so much else, stress testing will be a much more coordinated exercise in the Basel II world. As well as the business, country, and risk type dimensions already mentioned, it would be imperative that risk, finance, and management functions all work together to identify potential outcomes and to formulate robust mitigation plans to deal with these.

Why Do Stress Testing?

There are two important points to remember here about why you are conducting the exercise in the first place. First, if you are concerned about a potential future event, then you need to know what actions should be taken to mitigate the impacts of this event.

Secondly, if you want to look at your capital requirements under a stress event, this may give a completely new dimension to the classic “scenario planning” that has gone on before. This is not to say that there is no value in a scenario planning exercise, but it does not, of itself, answer any questions as to how much capital demands would increase should the hypothetical event become a reality. Ideally, an economic capital model should be used to answer this second question, but it needs to be recognized that there are issues here too. Unless you can estimate how the drivers of every risk type in your model would react to your stress event, you will struggle when you seek to estimate a capital impact. It may also be that the stress event itself does not impact the explicit drivers of your capital model for a particular risk type. In this case, enlightened expert judgment must still be used. In all cases, however, the outputs of the model must be treated with extreme caution. What you are doing is taking a mixture of historic data and management judgments as your inputs and from that calculating some form of quantitative output. As the majority of the input data can be neither accurate nor certain, the quality of the output must also be a reasonable estimate—but neither accurate nor certain.

It should be noted that just because a bank’s capital requirements would increase under an “extreme but plausible” scenario, it does not mean that additional capital is required in the current environment. Decisions around the appropriate buffer for such contingencies are very much down to senior management’s expert judgment. It is equally important that the regulators share this view, as this will, in part, color the level of capital that the firm is required to put up under Pillar 2.

The Stress-Testing Programme

Ideally, when constructing a stress-testing programme you should proceed along the following lines.

The most important initial step is to understand the nature of the event and to get senior management to specify it in sufficient detail. If this phase is not done thoroughly, the subsequent analysis will possibly be of limited value.

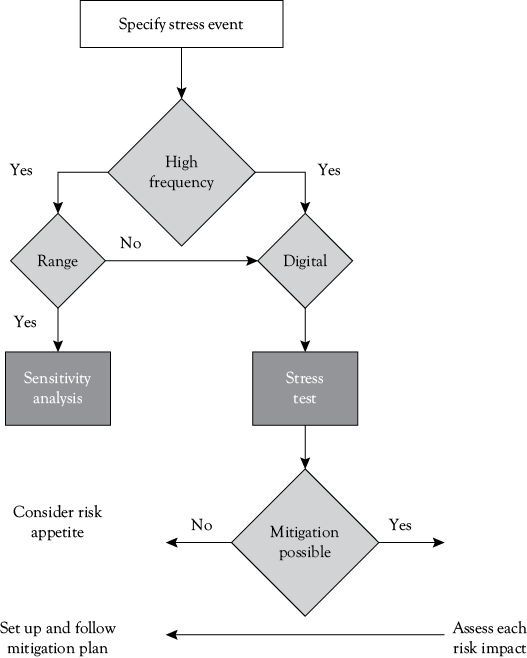

The following exhibit gives a simple view of the possible steps here.

Exhibit 4.2 Understand the nature of the stress event

Source: Author’s own.

The specification of the event should determine what the possible cause or causes are. If these are arising external to the financial institution, it may be that the effects are exacerbated by your trading partners being placed in similar conditions, with negative consequences for markets and liquidity. The frequency with which the event can occur also needs to be understood, so you can be aware whether this is an unlikely, one-off occurrence, or whether the potential negative consequences may re-occur periodically after the effects of the first occurrence have been fully absorbed.

For high-frequency events with a range of possible outcomes, a sensitivity analysis is recommended and Monte Carlo simulations are often employed, as discussed in another chapter. You do, however, still need to consider whether the use of linear approximations under a delta approach (as described earlier) is justified in any particular exercise.

For a lower-frequency event or where your event is digital in nature, a more comprehensive stress test is recommended. Where quantitative techniques are not appropriate, a scenario plan/analysis can still be performed. By using the term “digital” we are not excluding risk drivers, such as exchange rates, which fluctuate in value. The digital stress test would apply when this risk driver moves outside of its customary range (e.g., when a currency peg is removed). Another example of a digital event is a security event at one of your major branches or offices.

The exhibit does simplify what is, in effect, an inexact science. It should, however, inform thinking as to what the appropriate course of action is in terms of a full stress test/scenario analysis, or whether additional sensitivity analysis is required.

For the stress test/scenario plan, Exhibit 4.3 explores its implementation and continued running within the financial institution.

Exhibit 4.3 A sound stress testing programme

Source: Author’s own.

The Nature of the Stress Test

The relevance of the stress tests must be continually reassessed and the tests adjusted or re-run. In practice, where the portfolio has changed little from the previous exercise, and the stress test involved a lot of time-consuming manual work, as will be the case at a number of financial institutions, then a decision needs to be made on the frequency of re-running the exercise. This will be based on its perceived value to the institution and how the individual test builds into the comprehensive series of tests operated by the bank, but, in general, if something was a risk a month ago, it is probably still a risk this month and you will still need to consider whether anything has changed and the impact this has upon your organization.

From a practical perspective, it may make sense to reconsider the assumptions inherent within existing stress tests only when agreed triggers are breached. Ad hoc stress tests should then be considered in addition to existing tests as newly perceived risks arise.

CEBS CP12 on stress testing under the supervisory review process also makes the point that “the use of a broad range of stress tests as a complement to existing risk management tools is currently not widespread.” The number and complexity of stress tests must be proportional to the size and complexity of the institution, “taking into account their size, sophistication and diversification” (CEBS CP12 ST1). Where a bank has subsidiaries in a number of countries, this places additional requirements on the number of stress tests, in that “stress testing should in principle be applied at the same level as the ICAAP” (CEBS CP12 ST6).

With our “risk type owner” structure, we should consider one stress test per risk type. In addition to this, we must also consider all the stress tests inspired by particular concerns which cover a number of risk types either across the whole portfolio or for some part of it. A firm should probably consider more stress tests than its senior management can find time to discuss! Hence the need for a dedicated function providing filtered reports of the major risks to senior management.

Time Horizons

You should also consider the time horizon of the stress test itself. This may be a stress test playing out over a couple of weeks, if market risk-specific. A credit risk stress test may require a much longer time horizon to be considered, as the recovery from this will typically take much longer. Moreover, scenario modeling should not only look at the current portfolio of the bank, but also be applied to plans for future growth.

Probability and Stress Testing

Now we move on to discuss briefly the role of probability within stress testing. It is doubtful that a lot of science can be fruitfully applied to estimating probabilities of extreme events occurring. You could go so far as to say that where we can reliably estimate a probability, the event is probably not stressful enough! The regulatory guidance simply states that our stress test should be “extreme but plausible.” As long as you have an idea of the relative likelihood of various stress events, you can prioritize accordingly.

Where probability may have a role to play is in terms of outcomes. Especially in the case of a credit portfolio, rather than applying, for example, a two-notch downgrade across the portfolio, you could use a stressed transition matrix, which assigns probabilities of migrations across multiple grades. This can be refined to apply different transition probabilities to different parts of the portfolio.

Where you have access to this approach and can implement Monte Carlo simulation, you can actually generate a stressed loss distribution. Hence, as well as an expected impact, you can look at the worst-case impact with, say, 99 percent confidence. This is an attractive enhancement as the two events may have the same expected impact, but different 99th percentile worst-case impacts. This should mean that in an extreme scenario, one of the events has a much greater impact on the bank than the other and it should be this event that receives greater management attention.

Conclusion

Sensitivity analysis, stress testing, and scenario modeling are all developing techniques within financial services and they are currently used inconsistently between risk types. While they are common within market and credit risk, they are less commonly used in other risk areas. Increasingly, financial institutions will need to build a comprehensive framework for such testing to ensure that the senior management, as well as the regulators, really understand the risks that are being run by the firm.

It further needs to be recognized that management action is perhaps better facilitated by qualitative information. Moreover, a point estimate is probably more amenable to senior management discussion than a percentile in a distribution. This brings us to the conclusion of this discussion: whatever the challenges to the risk manager in conducting the stress test, there is a significant challenge to senior management in terms of understanding the models and assumptions used. The ideal of senior management providing a challenge to quantitative techniques used and having sufficient knowledge of their strengths and weaknesses to recommend appropriate mitigating action will not be easily achieved.

Stuart Burns would like to thank Cynthia Ong for her help in producing the various diagrams used in this chapter.