Chapter 8

Introducing HTML

In This Chapter

![]() Discovering how HTML was created

Discovering how HTML was created

![]() Creating HTML headers

Creating HTML headers

![]() Looking at the structural elements of HTML

Looking at the structural elements of HTML

![]() Exploring text and image elements

Exploring text and image elements

![]() Using HTML tables

Using HTML tables

The web today is much different than the web before, say, the year 2000 or so. Through the 1990s, as the web emerged, web pages were based on HTML, with limited use of JavaScript. Such web pages are called static web pages, and the web of that time is now referred to as the static web.

Late in the 1990s, a livelier web came into place, much more responsive to users. Now, when a user visits a web page, the web page is created on the spot through a series of database calls. The ads come from some databases, the header and footer from others, and the main content from others entirely.

All this content is poured into a page layout defined in CSS, with liberal use of JavaScript to make the page lively, dynamic, and responsive. Languages like Python are used for purposes such as interfacing with databases.

This new, livelier web was called Web 2.0 when it appeared, but is better-known today as the dynamic web.

In this chapter, we introduce HTML, the web’s core technology — but a technology that is, as we describe here, only part of a suite of technologies in the web pages of today.

Discovering How the Web Became What It Is

In the past, web pages were hand-crafted. Initially, every page was its own beast, hand-coded in HTML. The HTML standard was changing rapidly, and so were the browsers that displayed web pages — mainly Netscape Navigator and Microsoft Internet Explorer, with Firefox and Google’s Chrome coming along later.

There were even cultural aspects to your development and web browser choices. If you used a Windows PC and Microsoft tools for development, and the Internet Explorer browser for web surfing, you were a hopeless square. (That’s because it was mostly large corporations that were under “account control” by Microsoft that would do such a thing.) Most developers used Macs and Netscape standards and tools. Pages optimized for Netscape Navigator were considered cooler.

In the mid-1990s, style sheets became important. Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) was the standard that was chosen from among several competitors. CSS changed a lot in its early years, as did its implementation in browsers.

The final element of the core troika of early web development technologies is JavaScript. It was originally developed as LiveScript at Netscape, also in the mid-1990s. The name was changed to JavaScript shortly before widespread adoption, even though JavaScript has nothing to do with the Java runtime environment and programming language.

Web pages became quite complex. Each page was a somewhat volatile and hand-crafted mixture of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. (These three standards are called “the basic building blocks of the web” on the W3C site, w3c.org.) Because the functionality of these three technologies can overlap somewhat, every different web page was a new adventure.

Websites today are largely driven by databases. HTML and CSS and JavaScript still matter, of course. But they are used as much to create frameworks for database-generated content as for hand-crafted pages. (And yes, as a web professional today, you very much need to be able to do both.)

This chapter describes the first of these three core technical standards for web pages, HTML. Today’s web pages are just as likely to be crafted in DreamWeaver and programmed with PHP as created directly from HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

But knowing the basics of HTML, and being able to explain them to colleagues who want to know what a web page can and can’t do, is vital to an understanding of how the web works. With this knowledge in your hip pocket, you’ll be better able to carry out your role as a member of your web development team.

If you already know HTML, review this chapter to make sure you know the basics as well as you think you do, and then use this information to bring colleagues up to speed.

As with other original web technologies and approaches, there is also both a cultural and a credibility aspect to knowing these technologies well. You want to be able to add new HTML, tweak existing CSS, and sling JavaScript with the old hands as well as write clean PHP code with the new.

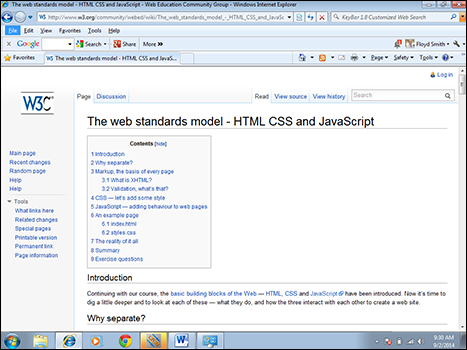

Figure 8-1: Visit W3C for basics on JavaScript programming and interaction with HTML and CSS.

Exploring the Creation of HTML

Just about everyone reading this book knows what HTML is. Still, it’s worthwhile to describe its creation and evolution because they’re still relevant to how the web as a whole, and web pages, are developed today.

The core of HTML is the use of “tags” — little pieces of code — to “mark up,” or put formatting or descriptive elements, into text.

Here’s an example of simple HTML:

I like to use <b>bold</b> sometimes and <i>italic</i> sometimes. And other times I like to add <a href="w3c.org">links</a>.

How does this show up? Like so:

I like to use bold sometimes and italic sometimes. And other times I like to add links.

Now, there has been a battle between two approaches to HTML since the early days. These are basically whether HTML is used for formatting or description.

If you believe HTML is used for formatting, you’re very happy with the bold (<b>) and italic (<i>) tags. However, some web developers preferred to use tags such as <strong> and <em>, for emphasis. The idea was that it was up to the browser, or other display software, to decide what strong and emphasis meant.

With the clarity given by hindsight, it’s clear that this latter idea is ridiculous – although some people still swear by it. Writers and editors are used to using bold and italics and underlining for certain purposes in print — and they’re happy to continue doing that in the online medium. But they weren’t ready to stop worrying about whether words were emphasized by bolding, italics, or some other convention.

So HTML continues to be used for formatting. And it will probably be used that way forever.

The following sections describe core elements of HTML. It’s worth reviewing them because every web page has to have these elements — even if, in some cases, they’re now being implemented more often in CSS or JavaScript rather than HTML.

Discovering Header Elements

The top part of an HTML document is called the header, and is surrounded by the <head> and </head> tags. The header usually contains mostly header-specific tags, described here. These tags define elements that apply to the page as a whole.

The body of the web page, by contrast, is surrounded by the <body> and </body> tags. It includes the actual web page content and is where the rest of the tags are used.

Header tags include

- <title> and </title>. The name of the web page. Most browsers show it in the header bar at the top of the page, above the page itself — or in the tab, if you’re using tabbed browsers.

- <meta>. The <meta> tag contains general information about the page that’s used in various ways. The contents aren’t really specified officially, but a few conventions have grown up. You can use the meta tag to specify a description of the site and various keywords that you want search engines to use, but most search engines today don’t take much notice of the <meta> tag.

- <link> and </link>. This tag is mostly used to link to stylesheets written using CSS.

- <style>. This is a place to put CSS code that applies to this specific page. If you also link to one or more CSS stylesheets, the CSS code contained in the <style> tag will override the CSS code in the stylesheet for use on the current page.

- <script> and </script>. This is where you commonly put all the JavaScript on a page between the <script> and </script> tags.

Making Use of Core Structural Elements

HTML has several core structural elements. These elements describe the overall layout of a web page.

Search engines vary their algorithms — the rules they use — over time. But a few key elements tend to be used over and over to analyze a web page and what’s important in it. The core structural elements of a web page are a big part of this.

Headers are perhaps the most important ongoing element for search engine success. Any web page worth bothering with is going to put core topical keywords in its headers.

The problem is that HTML and CSS can be used to create what look like second-level and third-level headers without actually using the HTML <H2> and <H3> tags to do it. Here are core structural elements of HTML:

- <h1> and </h1> through <h6>/<h6>. These are HTML headers. A lot of web developers seem to pride themselves on not using HTML header tags. Why? Stop tricking your users and search engines; use search-engine-recognizable header tags in your web page layouts.

- <p> and </p>. This is the HTML paragraph tag. People used to use the <P> tag as a way to separate one paragraph (thus the <P>) from the next. Or they would use the <br>, or “break” tag, which is only supposed to indicate a line break, not a meaningful separation of chunks of text.

- <blockquote> and </blockquote>. This HTML tag pair indicates a block of quoted text. It’s a great example of the different types of HTML tags, those that control formatting and those that indicate meaning. This tag pair displays text indented from the left edge of other text.

Using List Elements

Lists are highly recommended for frequent use on your web pages. They’re easy for the reader to scan and quickly pick out key points.

Lists are also good for writers — they make the writer get to the point quickly. This is very important on the web, where people scan pages hurriedly, looking for a key fact or insight, then hurriedly move on.

The main types of lists that you’ll use are bulleted lists and numbered lists. Both are great for helping readers pick out key points. Numbered lists work when there are steps or some other process or procedure. Web pages tend to have a lot of bulleted lists, so use numbered lists where you sensibly can.

Here are the most commonly used list elements of HTML:

- <ul> and </ul>: Use these tags to surround an entire unordered (bulleted) list.

- <ol> and </ol>: Use these tags to surround an entire ordered (numbered) list.

- <li> and </li>: Use these tags to surround each item in an unordered (that is, bulleted) or ordered (numbered) list.

You can also create a definition list. A definition list is like a bulleted list, but each bullet item is a definition term — the term that’s being defined, usually displayed in bold — followed by the definition itself. The definition list gives you another tool for breaking up your web page, avoiding long flows of paragraph text.

Here are the tags for definition lists:

- <dl> and </dl>: This is not a tag for putting information on the “down low” (keeping it secret); instead, use these tags to create a definition list.

- <dt> and </dt>; <dd> and </dd>: “dd” stands for “definition data.” The contents of a definition list include the terms that you’ll define (<dt>) and the definitions themselves (<dd>).

Working with Text Formatting and Image Elements

Text and images are the core elements of nearly all web pages. Only a few HTML attributes were available, in the early days, to affect how they were displayed onscreen, and CSS was not yet invented at that time. So these few tags received a lot of use, and even abuse, as web developers tried very hard to create sophisticated-looking web pages with the crude tools at their disposal.

Formatting text directly is said to be somewhat against the spirit of HTML, but people care a great deal about how text appears onscreen. HTML was pushed to its limits to create page layout and text formatting, with much difficulty across different browsers, different browser versions, and different types of computers and screen resolutions. Now, browsers are far more standardized, and the same goal is reached more effectively with a combination of simpler HTML code and CSS.

Here are the main tags that format text directly:

- <b> and </b>. Tags that render the enclosed text bold.

- <i> and </i>. Tag pair that renders enclosed text in italics.

- <font> and </font>. Tag pair that renders enclosed text in a specified font.

- <span> and </span>. Designates enclosed text for formatting commands.

- <a> and </a>. Defines an anchor or hyperlink and formats the enclosed text in a way that designates it as a hyperlink — usually underlined and in blue. The hyperlink is defined by the href attribute, as follows: <a href = "url">, where “url” is a web page address.

The tags for putting images into a flow of text are

- <img>. The image tag specifies that an image will be placed in the flow of text before and after the tag. As with the anchor tag, the image location is defined by the href attribute.

- <media>. An early way of specifying a multimedia element, such as a video clip.

Looking at Table Elements

Table tags were originally designed to be used for creating tables within a web page, with rows and columns and a caption describing the table. However, web developers badly wanted their pages to look better, and they didn’t have many tools to do it in HTML.

So web developers started making the entire web page a table, and putting text and graphics within the rows and columns. This did give a lot of control. However, it also made web page HTML very complicated and easy to “break,” in ways that were hard to find and fix.

Fairly quickly, web developers started using nested tables for page layout — perhaps one table for the top of the page, another for a left-hand column or “rail” with navigation, and a third for the main page content. This went within an overarching table that put the rails, main column, and so forth in place. If you wanted an actual table in the usual sense — a formatted set of rows and columns to organize some information — that just went within all the other tables.

A lot of the energy behind the creation and adoption of CSS was an attempt to get away from all these tables and the problems they created.

Commonly used table tags include <th> and </th> for a header cell, <thead> and </thead> for a group of header cells, <col> and </col> to define a column, and <colgroup> and </colgroup> to group columns together. <tr> and </tr> defined rows, and <td> and </td> defined a single cell in the table. The <caption> and </caption> tags gave the table’s caption — as usual with HTML, formatted and placed according to each web browser’s interpretation of the tag, beyond the control of the web developer.

The W3C website has a course on JavaScript that also relates its use to HTML and CSS, shown in Figure

The W3C website has a course on JavaScript that also relates its use to HTML and CSS, shown in Figure  On the web, you shouldn’t use underlining for any purpose except hyperlinks. People are used to clicking on underlined text, and it’s just too confusing if you try to do it any other way. (And also, always underline linked text — unless you come up with some other way of signaling “this is a link” that’s extremely clear and obvious.)

On the web, you shouldn’t use underlining for any purpose except hyperlinks. People are used to clicking on underlined text, and it’s just too confusing if you try to do it any other way. (And also, always underline linked text — unless you come up with some other way of signaling “this is a link” that’s extremely clear and obvious.) The HTML header tags,

The HTML header tags,