Organizational Grit

by Thomas H. Lee and Angela L. Duckworth

HIGH ACHIEVERS HAVE extraordinary stamina. Even if they’re already at the top of their game, they’re always striving to improve. Even if their work requires sacrifice, they remain in love with what they do. Even when easier paths beckon, their commitment is steadfast. We call this remarkable combination of strengths “grit.”

Grit predicts who will accomplish challenging goals. Research done at West Point, for example, shows that it’s a better indicator of which cadets will make it through training than achievement test scores and athletic ability. Grit predicts the likelihood of graduating from high school and college and performance in stressful jobs such as sales. Grit also, we believe, propels people to the highest ranks of leadership in many demanding fields.

In health care, patients have long depended on the grit of individual doctors and nurses. But in modern medicine, providing superior care has become so complex that no lone practitioner, no matter how driven, can do it all. Today great care requires great collaboration—gritty teams of clinicians who all relentlessly push for improvement. Yet it takes more than that: Health care institutions must exhibit grit across the entire provider system.

In this article, drawing on Tom’s decades of experience as a clinician and health care leader and Angela’s foundational studies on grit, we’ve integrated psychological research at the individual level with contemporary perspectives on organizational and health care cultures. As we’ll show, in the new model of grit in health care—exemplified by leading institutions like Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic—passion for patient well-being and perseverance in the pursuit of that goal become social norms at the individual, team, and institutional levels. Health care, because it attracts so many elite performers and is so dependent on teamwork, is an exceptionally good place to find examples of organizational grit. But the principles outlined here can be applied in other business sectors as well.

Developing Individuals

For leaders, building a gritty culture begins with selecting and developing gritty individuals. What should organizations look for? The two critical components of grit are passion and perseverance. Passion comes from intrinsic interest in your craft and from a sense of purpose—the conviction that your work is meaningful and helps others. Perseverance takes the form of resilience in the face of adversity as well as unwavering devotion to continuous improvement.

The kind of single-minded determination that characterizes the grittiest individuals requires a clearly aligned hierarchy of goals. Consider what such a hierarchy might look like for a cardiologist: At the bottom would be specific tasks on her short-term to-do list, such as meetings to review cases. These low-level goals are a means to an end, helping the cardiologist accomplish mid-level goals, such as coordinating patients’ care with other specialists and team members. At the top would be a goal that is abstract, broad, and important—such as increasing patients’ quality and length of life. This overarching goal gives meaning and direction to everything a gritty individual does. (See the exhibit “A cardiologist’s goal hierarchy.”) Less gritty people, in contrast, have less coherent goal hierarchies—and often, numerous conflicts among goals at every level.

A cardiologist’s goal hierarchy

In this simplified illustration, immediate, concrete goals sit at the bottom. These support broader goals at the next level, which in turn support an overarching primary goal that provides meaning and direction.

It’s important to note that assembling a group of gritty people does not necessarily create a gritty organization. It could instead yield a disorganized crowd of driven individuals, each pursuing a separate passion. If everyone’s goals aren’t aligned, a culture won’t be gritty. And, as we’ll discuss in more detail later, it takes effort to achieve that alignment.

Take Mayo Clinic. It is unambivalently committed to a top-level goal of putting patients’ needs above all else. It lays out that goal in its mission statement and diligently reinforces it when recruiting. Mayo observes outside job candidates for two to three days as they practice and teach, evaluating not just their skills but also their values—specifically, whether they have a patient-centric mission. Once hired, new doctors undergo a three-year evaluation period. Only after they’ve demonstrated the needed talent, grit, and goal alignment are they considered for permanent appointment.

How can you hire for grit? Questionnaires are useful for research and self-reflection (see the sidebar “Gauging Your Grit”), but because they’re easy to game, we don’t recommend using them as hiring tools. Instead, we recommend carefully reviewing an applicant’s track record. In particular, look for multiyear commitments and objective evidence of advancement and achievement, as opposed to frequent lateral moves, such as shifts from one specialty to another. When checking references, listen for evidence that candidates have bounced back from failure in the past, demonstrated flexibility in dealing with unexpected obstacles, and sustained a habit of continuous self-improvement. Most of all, look for signs that people are driven by a purpose bigger than themselves, one that resonates with the mission of your organization.

Mayo, like many gritty organizations, develops most of its own talent. More than half the physicians hired at its main campus in Rochester, Minnesota, for example, come from its medical school or training programs. One leader there told us those programs are seen as “an eight-year job interview.” When expanding to other regions, both Mayo and Cleveland Clinic prefer to transfer physicians trained within their systems rather than hire local doctors who may not fit their culture.

Creating the right environment can help organizations develop employees with grit. (The idea of cultivating passion and perseverance in adults may seem naive, but abundant research shows that character continues to evolve over a lifetime.) The optimal environment will be both demanding and supportive. People will be asked to meet high expectations, which will be clearly defined and feasible though challenging. But they’ll also be offered the psychological safety and trust, plus tangible resources, that they need to take risks, make mistakes, and keep learning and growing.

At Cleveland Clinic, physicians are on one-year contracts, which are renewed—or not—on the basis of their annual professional reviews (APRs). These include a formal discussion of career goals. Before an APR, each of the clinic’s 3,600 physicians completes an online assessment, reflects on his or her progress over the past year, and proposes new objectives for the year ahead. At the meetings, physicians and their supervisors agree on specific goals, such as improving communication skills or learning new techniques. The clinic then offers relevant courses or training along with the financial support and “protected time” the physicians might need to complete it. Improvement is encouraged not by performance bonuses but by giving people detailed feedback about how they’re doing on a host of metrics, including efficiency at specific procedures and patient experience. The underlying assumption is that clinicians want to improve and that the organization, and their supervisors in particular, fully backs their efforts to reach targets that may take a year or more to reach.

Building Teams

Gritty teams collectively have the same traits that gritty individuals do: a desire to work hard, learn, and improve; resilience in the face of setbacks; and a strong sense of priorities and purpose.

In health care, teams are often defined by the population they serve (say, patients with breast cancer) or the site where they work (the coronary care unit). Gritty team members may have their own professional goal hierarchies, but each will embrace the team’s high-level goal—typically, a team-specific objective, such as “improve our breast cancer patients’ outcomes,” that in turn supports the organization’s overarching goal.

Many people in health care associate commitment to a team with the loss of autonomy—a negative—but gritty people view it as an opportunity to provide better care for their patients. They see the whole as greater than the sum of its parts, recognizing that they can achieve more as a team than as individuals.

In business, teams are increasingly dispersed and virtual, but the grittiest health care teams we’ve seen emphasize face-to-face interaction. Members meet frequently to review cases, set targets for improvement, and track progress. In many instances the entire team discusses each new patient. These meetings reinforce the sense of shared purpose and commitment and help members get to know one another and build trust—another characteristic of effective teams.

That’s an insight that many health care leaders have come to by studying the description of the legendary six-month Navy SEAL training in Team of Teams, by General Stanley McChrystal. As he notes, the training’s purpose is “not to produce supersoldiers. It is to build superteams.” He writes, “Few tasks are tackled alone … The formation of SEAL teams is less about preparing people to follow precise orders than it is about developing trust and the ability to adapt within a small group.” Such a culture allows teams to perform at consistently high levels, even in the face of unpredictable challenges.

Commitment to a shared purpose, a focus on constant improvement, and mutual trust are all hallmarks of integrated practice units (IPUs)—the gold standard in team health care. These multidisciplinary units provide the full cycle of care for a group of patients, usually those with the same condition or closely related conditions. Because IPUs focus on well-defined segments of patients with similar needs, meaningful data can be collected on their costs and outcomes. That means that the value a unit creates can be measured, optimized, and rewarded. In other words, IPUs can gather the feedback they need to keep getting better.

UCLA’s kidney transplant IPU is a prime example. Two years after the 1984 passage of the National Organ Transplant Act, which required organ transplant programs to collect and report data on outcomes such as one-year success rates, Kaiser Permanente approached UCLA about contracting for kidney transplantation. This dominant HMO would increase its referrals to UCLA if UCLA would accept a fixed price for the entire episode of care (a “bundled payment”). After taking the deal, UCLA had an imperative to deliver great outcomes (or risk public humiliation and loss of referrals) and be efficient (or risk losing money under the bundled payment contract).

The team has grown to be one of the largest in the country, and its success rates (risk-adjusted patient and graft survival) have been significantly higher than national benchmarks almost every year. With medical advances and public reporting, kidney transplantation success rates have improved across the country—but UCLA has stayed at the front of the pack.

Gritty Organizations

If gritty individuals and teams are to thrive, organizations need to develop cultures that make them, in turn, macrocosms of their best teams and people.

So organizations benefit from making their goal hierarchies explicit. If an organization declares that it has multiple missions, and can’t prioritize them, it will have difficulty making good strategic choices.

Another danger is promoting a high-level objective that people won’t embrace. In health care making cost cutting or growth in market share the top priority is unlikely to resonate with caregivers whose passion is improving outcomes that matter to patients.

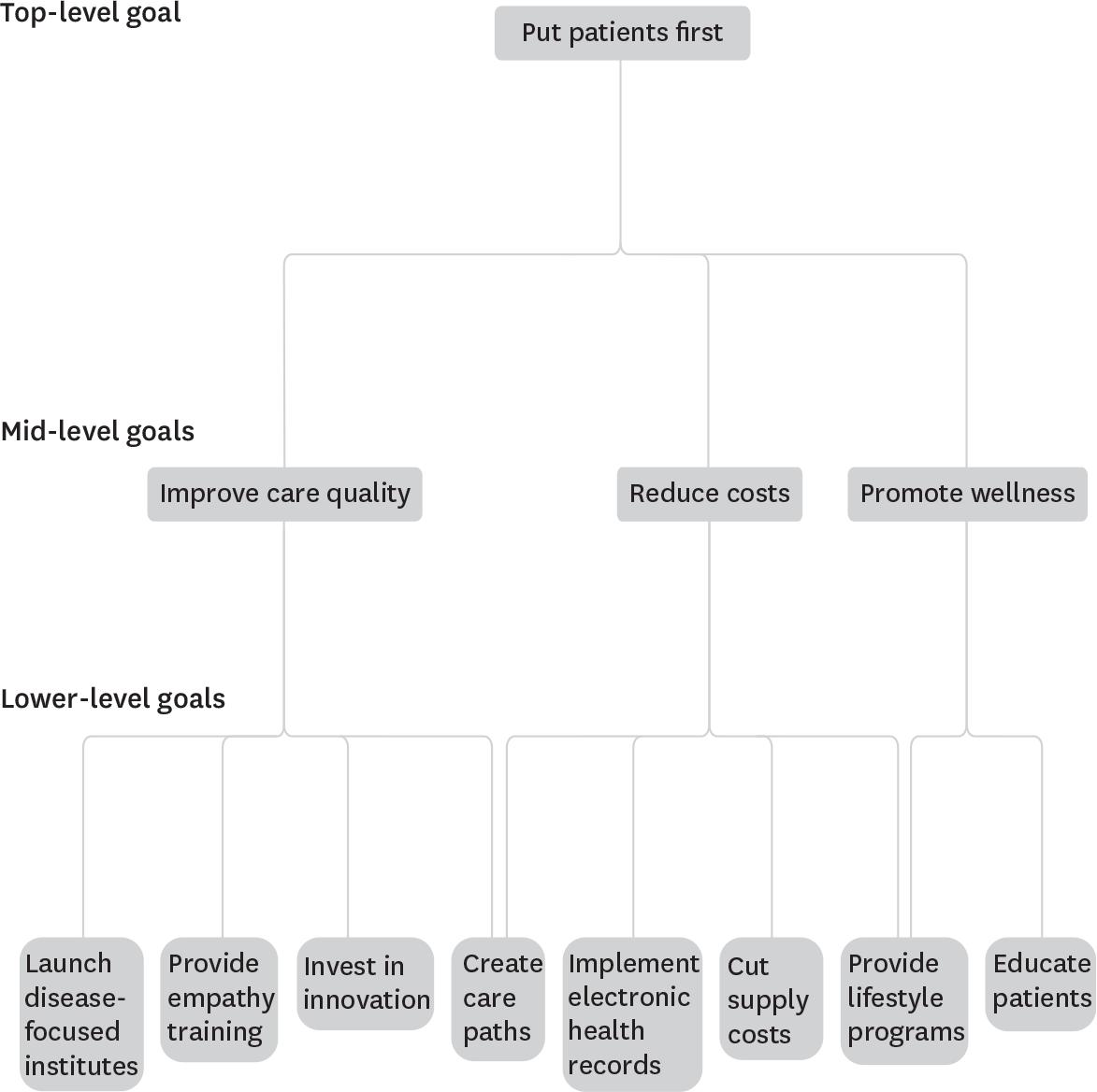

In our experience, every gritty health care organization has a primary goal of putting patients first. In fact, we believe a health care organization can’t be gritty if it doesn’t put that goal before everything else. (See the exhibit “Aligning organizational objectives.”) Though it’s challenging to suggest that other needs (such as those of doctors or researchers) come second or third, if patients’ needs are not foremost, decisions tend to be based on politics rather than strategy as stakeholders jockey for resources. This doesn’t mean an organization can’t have other goals; Mayo, for instance, also values research, education, and public health. But those things are subordinate to patient care.

Aligning organizational objectives

Gritty health care institutions have clear goal hierarchies, like the hypothetical schematic below. As with individual and team hierarchies, lower-level goals support those at the next tier, in service of a single, overarching top-level goal or mission.

Of course, even when the high-level goal is clear and appropriate, rhetoric alone won’t suffice to promote it—and can even backfire. If an organization’s leaders don’t use the goal to make decisions, it will undermine their credibility.

Consider how Cleveland Clinic responded when it learned that a delayed appointment had caused hours of suffering for a patient with difficulty urinating. The clinic began asking everyone requesting an appointment whether he or she wanted to be seen that day. Offering that option required complex and costly changes in how things were done, but it clearly put patients’ needs first. As it happened, the change was rewarded with tremendous increases in market share, but this was a happy side effect, not the main intent of the change.

As this story shows, clarity around high-level goals can be a competitive differentiator in the market and have a valuable impact within the organization as well. Data from Press Ganey demonstrates that when clinicians and other employees embrace their organization’s commitment to quality and safety, and when those goals reflect their own, it leads not only to better care but also to better business results.

But how can leaders help translate the top-level organizational goal into practical activities for teams and individuals? Seven years ago Cleveland Clinic took an important step that helped define its culture and direction. Toby Cosgrove, the CEO at the time, had all employees engage in a half-day “appreciative inquiry” program, in which personnel in various roles sat at tables of about 10 and discussed cases in which the care a patient received had made them proud. The perspectives of physicians, nurses, janitors, and administrative staff were intertwined, and the focus was on positive real-life examples that captured Cleveland Clinic at its best.

The question posed was, What made the care great in this instance, and how could Cleveland Clinic make that greatness happen every time? The cost for taking its personnel offline for these exercises was estimated to be $11 million, but Cosgrove considers it one of the most powerful ways he helped the organization align around its mission.

Another tactic is to establish social norms that support the top-level goal. At Mayo Clinic the social norm for clinicians is to respond to pages about patients immediately. They don’t finish driving to their destination; they pull off the road and call in. They don’t finish writing an email or conclude a conversation, even with a patient. They excuse themselves and answer the page.

“What happens if you don’t answer your beeper right away?” we asked several people at Mayo. “You won’t do well here,” several told us. Another joked, “The earth will open up and swallow you.” A third said, “The last thing you want is to have people say, ‘He’s the kind of guy who doesn’t answer his page.’” It’s part of a bigger picture. There is more to “the Mayo Way” than a dress code (and there is a dress code). It includes answering your beeper, working in teams, and putting patients’ needs first.

Another fundamental characteristic of gritty organizations is restlessness with the status quo and an unrelenting drive to improve. Fostering that restlessness in a health care organization is a real test of leadership, because health care is full of people who are well trained and work hard—but often are not receptive to hearing that change is needed. However, a goal of “preserving our greatness” is not a compelling argument for change or an attraction for gritty employees. The focus instead should be on health care’s true customers, patients—not just on providing pleasant “service” but on the endless quest to meet their medical and emotional needs.

It also helps to promote inside the organization something Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck calls a “growth mindset”—a belief that abilities can be developed through hard work and feedback, and that major challenges and setbacks provide an opportunity to learn. That, of course, requires leadership to accept, and even publicly communicate, complications and errors—something that doesn’t always come easily in health care. But leaders that are explicit about the need for calculated risk taking, reducing mistakes, and continual learning tend to be the ones who actually inspire real growth in their organizations.

Crises offer special opportunities for growth—and in particular to strengthen culture. Organizations that have provided care after natural disasters or terrorist attacks have found that the experience leads to powerful bonding, a reinforced sense of purpose, the desire to excel, and a renewed commitment to organizational goals.

For example, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, in 2005, a local hospital affiliated with Ochsner Health System faced a series of incredible challenges, including power outages, flooding, overcrowding, and inadequate food and supplies. But throughout, morale remained high, because the employees all pulled together and performed duties outside their usual roles. Physicians served meals, for instance, and nurses cleaned units. “The team that was here throughout the storm has a relationship that can only be duplicated by soldiers in combat,” the hospital’s vice president of supply chain and support services told Repertoire magazine. “There’s such respect and trust for one another.”

Responding to self-generated crises can be a little trickier, however. But here, patient stories can be powerful drivers of improvement—especially if the stories are mortifying and involve “one of our own.” At Henry Ford Health System, for example, every new employee watches a video depicting the experience of a physician in the system’s intensive care unit, Rana Awdish, who nearly bled to death in the ICU in 2008 when a tumor in her liver suddenly ruptured. She was in severe shock and had a stroke; she was also seven months pregnant, and the baby did not survive.

As her conditioned worsened, Awdish heard her own colleagues say, “She’s trying to die on us” and “She’s circling the drain”—things that she herself had said when working in the same ICU. Hearing her describe her experience made her colleagues realize that her doctors were focused on the problem but not on her as a human being, and that this probably was happening a lot within Henry Ford. The crisis led leadership to commit to the goal of treating every patient with empathy all the time. Today every employee at Henry Ford has seen the video, and the goal of being reliably empathic is clearly understood. Sharing Awdish’s story is just one of the interventions that has occurred at Henry Ford, and during the campaign that followed the organization saw most physician-related measures of patient experience improve by five to 10 percentage points.

The Gritty Leader

Ralph Waldo Emerson observed that organizations are the lengthened shadows of their leaders. To attract employees, build teams, and develop an organizational culture that all have grit, leaders should personify passion and perseverance—providing a visible, authoritative role model for every other person in the organization. And in their personal interactions, they too must be both demanding—keeping standards high—and supportive.

Consider Toby Cosgrove. He was a diligent student but, because he had dyslexia that was undiagnosed until his mid-thirties, his academic record was lackluster. Nevertheless, he set his sights on medical school, applying to 13. Just one, the University of Virginia, accepted him. In retrospect, “the dyslexia reinforced my determination and persistence,” Cosgrove told us, “because I had to work more hours than anybody else to get the same result.”

In 1968, Cosgrove’s surgical residency was interrupted when he was drafted. He served a two-year tour as a U.S. Air Force surgeon in Vietnam. Upon his return home, he completed his residency and then joined Cleveland Clinic in 1975. “Everybody told me not to become a heart surgeon,” he said. “I did it anyway.” Indeed, Cosgrove performed more cardiac surgeries (about 22,000) than any of his contemporaries. He pioneered several technologies and innovations, including minimally invasive mitral valve surgery, earning more than 30 patents.

Cosgrove’s development as a world-class surgeon is a case study in grit. “I was informed that I was the least talented individual in my residency. But failure is a great teacher. I worked and worked and worked at refining the craft,” he told us. “I changed the way I did things over time. I used to take what I called ‘innovation trips’—trips all over the world to watch other surgeons and their techniques. I’d pick things up from them and incorporate them in my practice. I was on a constant quest to find ways to do things better.”

Cosgrove was named CEO of Cleveland Clinic in 2004. The passion and perseverance that made him great as a surgeon and as the head of a cardiac care team would soon be tested in his new role as leader of more than 43,000 employees. “I decided I had to become a student of leadership,” Cosgrove recalls. “I had stacks of books on leadership, and every night when I came home, I would go up to my little office and read. And then I called up Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter.” Porter, widely considered the father of the modern field of strategy, invited Cosgrove to visit. “He talked with me for two hours. After that, I got him to come to Cleveland. Since then, we’ve been sharing ideas,” Cosgrove says. Porter helped him understand that as CEO he needed to be more than a renowned surgeon and an enthusiastic leader. He needed to evolve the organization’s strategy, focusing on how to create value for patients and achieve competitive differentiation in the process.

Cosgrove scrutinized Cleveland Clinic’s quality data, and while its mortality statistics were similar to those of other leading institutions, performance on other metrics—especially patient experience—left much to be desired. “People respected us,” he says, “but they sure didn’t like us.” In 2009 he hired Jim Merlino, a young physician who had left the clinic unhappily after the death of his father there, and made him chief experience officer. Cosgrove asked Merlino to fix the things that had driven him away.

Cosgrove supported Merlino’s many innovative ideas, including having all employees go through the appreciative inquiry exercise, and making an internal training film, an “empathy video” that is so powerful it has been watched by many outside the clinic, getting more than 4 million views on YouTube. As a result of these efforts and many others, Cleveland Clinic moved from the bottom quartile in patient experience to the top.

The institutional changes Cosgrove and his team have accomplished are too numerous to catalog, but here are a few: Swapping parking spaces so that patients, not doctors, are closest to the clinic’s entrances. Moving medical records from hard copy to electronic storage. Developing standard care paths to ensure consistency and optimize the quality of care. Refusing to hire smokers and, recently, in response to the national opioid crisis, doing random drug testing of all Cleveland Clinic staff, including physicians and executives.

These changes weren’t always popular when they were introduced. But when he knows he’s right, Cosgrove stays the course. A placard he keeps on his desk reminds him “What can be conceived can be created.”

It’s hard to argue with the results achieved during his 13-year tenure as CEO. In addition to the improvements in patient experience, revenue grew from $3.7 billion in 2004 to $8.5 billion in 2016, and total annual visits increased from 2.8 million to 7.1 million. Quality on virtually every available metric has risen to the top tier of U.S. health care.

When Cosgrove gave his first big speech as CEO, he gave out 40,000 lapel buttons that said, “Patients First.” We asked if some of his colleagues rolled their eyes. “Yes, a lot of them did,” he said. “But I made the decision that I was going to pretend I didn’t see them.”

Cosgrove showed grit. And led an organization that has become his reflection.

Originally published in September–October 2018. Reprint R1805G