IQ skills: dealing with problems, tasks and money

Being a smart manager is different from being a smart intellectual. Brilliant professors rarely emerge as great managers. Conversely, many of the best entrepreneurs today are college drop outs. Bill Gates, Lawrence Ellison, Mukesh Ambani, Mark Zuckerberg and Steve Jobs have all made billions without the need for a degree.

Asking great managers what makes them great is an exercise in toadying and ingratiation which yields little more than platitudes and self-congratulation. I have tried it: it is not an exercise worth doing once, let alone repeating. For the most part they will talk about things like ‘experience’ and ‘intuition’. This is deeply unhelpful. You cannot teach intuition. Experience is a recipe for keeping junior managers junior until they have grown enough grey hairs to become part of the management club. I had to find out another way of discovering how managers thought, short of wiring them up to machines all day. So I did the next best thing: I decided to watch them work. Watching people work is invariably more congenial than actually doing the work.

Each person and each day is unique. Some people prefer face-to-face work rather than dealing through email; some days are totally consumed by a couple of big meetings; some people work longer and a few work less. But once we stripped away all these variances, we found these familiar patterns to a manager’s working day:

- high fragmentation of time

- management of multiple and competing agendas

- management of multiple constituencies

- constant flow of new information requiring reaction, change, adjustment

- low amounts of time working alone.

This is a pattern which is familiar to most managers. It has been compared to juggling while trying to run a marathon in a series of 100-metre sprints without dropping any of the balls. It is a world in which it is very easy to be busy but very difficult to make an impact. Activity is not a substitute for achievement. The challenge for managers today is to do less and achieve more.

At this point, pause to consider what you do not see in the normal management day:

- decision making using formal tools, such as Bayesian analysis and decision trees

- problem solving either by sitting alone and thinking deeply or by working in a group with a formal problem-solving technique;

- formal strategic analysis of the business.

Many MBA tools are notable by their absence from the daily lives of most managers: organisational and strategic theory go missing; financial and accounting tools remain functionally isolated within finance and accounting; marketing remains a mystery to most people in operations or IT.

The absence of these tools from most managers’ days does not make them irrelevant. They may be used sparingly, but at critical moments. Most organisations would not survive long if all their managers were conducting non-stop strategic reviews of the business. But a good strategic review once in five years by the CEO can transform the business.

By now my search for the management mindset was becoming lost in the whirl of activity that is the standard management day. It looked like great managers did not need to be intellectually smart and did not need the standard intellectual and analytical tools that appear in books and courses. But it would be a brave person who accused Bill Gates and Richard Branson of being dumb. All the leaders and managers we interviewed were smart enough to get into positions of power and influence. They were smart, but not in the conventional way of schools. Management intelligence is different from academic intelligence.

We decided to dig deeper, thereby breaking the golden rule ‘when in a hole, stop digging’. We hoped we were not digging a hole. We hoped we were digging the foundations of understanding the management mindset. We eventually found these foundations – explored in the following sections of this chapter – all of which can be learned and acquired by any manager:

Starting at the end: focus on outcomes

Achieving results: performance and perceptions

Making decisions: acquiring intuition fast

Solving problems: prisons and frameworks – and tools

Strategic thinking: floors, romantics and the classics

Setting budgets: the politics of performance

Managing budgets: the annual dance routine

Managing costs: minimising pain

Surviving spreadsheets: assumptions, not maths

Knowing numbers: playing the numbers game

If we were being intellectually rigorous, not all of these skills might exist in a chapter on management IQ. But there is some method behind the randomness.

Outcome focus and achieving results (Starting at the end and Achieving results) are included in this chapter because they are at the heart of the effective manager’s mindset. The way an effective manager thinks is driven by the need to drive results and achieve outcomes. This creates a style of thinking which is highly pragmatic, fast-paced and quite unlike anything you normally find in textbooks and academia. It is about achievement, not activity.

Making decisions, Solving problems and Strategic thinking are classic IQ skills. There is a huge difference between how textbooks say managers should think and how they really think. Textbooks look for the perfect answer. The perfect solution is the enemy of the practical solution. Searching for perfection leads to inaction. Practical solutions lead to what good managers want: action. For many managers, the real problem is not even finding the answer: the real challenge is finding out the question. The really good managers spend more time working out what the question is, before attempting to find the pragmatic answer.

Setting budgets, Managing budgets, Managing costs, Surviving spreadsheets and Knowing numbers could be called FQ – financial quotient. We expected to find that Finance and Accounting is 100 per cent IQ. We were 100 per cent wrong. In theory, financial management is a highly objective and intellectual exercise in which answers are either right or wrong: the numbers do or do not add up. For managers, the intellectual challenge is the minor part of the challenge. The major part of the challenge is not intellectual: it is political. Most financial discussions and negotiations are political discussions about money, power, resources, commitments and expectations. In many ways, financial management could better belong in the PQ (political quotient) chapter. Out of deference to financial theory, it is included in this, the IQ chapter.

In the sections which follow, we will pay our dues to theory. Theory is not useless: good theory creates a framework for structuring and understanding unstructured and complex issues. The main focus, however, is on the practice of how managers develop and deploy these IQ skills in practice.

2.1 Starting at the end: focus on outcomes

Managers have long been told ‘first things first’. This is tautological nonsense: it depends on what you define as ‘first’. In practice, managers do not start at the start. Effective managers start at the end.

For speed readers, let’s repeat the message: effective managers start at the end.

Working backwards from the desired outcome, rather than shambling forwards from today is at the heart of how good managers think and work. This outcome focus is essential because it achieves the following:

- creates clarity and focuses on what is important

- pushes people to action, not analysis

- finds positive ways forward, rather than worrying about the past

- simplifies priorities

- helps to identify potential obstacles and avoid them.

Outcome focus is a relatively easy discipline to learn. It requires asking the same four questions time and time again:

- What outcome do I want to achieve from this situation?

- What outcome does the other person expect from this situation?

- What are the minimum number of steps required to get there?

- What are the consequences of this course of action?

Keep asking these four questions relentlessly and you will find the fog of confusion lifts from most situations, and you can drive a team to action.

1 What outcome do I want to achieve from this situation?

Asking this question drives us into action and gives people a sense of clarity and purpose. It is also a way of taking control of a situation and gaining benefit from it. It is a way of avoiding becoming dependent on other people’s agendas, being purely reactive, or of slipping into analysis paralysis. Two examples will make the point:

Example one

A project was going horribly wrong: it threatened to go over time and budget. The team was having an inquest, which was rapidly turning into the normal blame game of ‘he said, she said, I said no, she said…’ Things were turning nasty. Then the team leader stopped the debate and asked: ‘OK, we have two weeks left on the project. The question is this: what can we do in the next two weeks to achieve a satisfactory outcome?’ Suddenly, the debate turned from defensive analysis into a positive discussion about what the team could do. The leader had focused the team on outcomes and action, not on problems and analysis.

Example two

The analyst had done a great job. She had compiled a mountain of data. The result was that her draft presentation was indigestible. Every piece of datum was so good it was hard to see what to leave out. So her manager asked her to focus on what she wanted to achieve from the presentation. The desired outcome was very simple: agree to a new project. Suddenly, it was easy to focus on a short story line which could persuade the decision maker about the project. The discussion was no longer ‘what shall we leave out of the presentation?’ but ‘what is the minimum we need to include to make our case?’ About 90 per cent of the presentation disappeared into an appendix which was never read. The analyst had learned that presentations and reports are not complete when there is nothing left to say or write: they are complete only when it is impossible to say or write any less. Brevity is much harder than length. Presentations and reports are like diamonds: they benefit greatly from good cutting.

2 What outcome does the other person expect from this situation?

Most managers are serving clients of some sort. Their client may be their boss, a colleague or an external partner. One way or the other, managers are supporting other people’s agendas. Understanding what the other person wants is a very simple way of clarifying what the desired outcome of any situation is. Achieving clarity on this question enables the manager to:

- simplify and focus on the task in hand – the extraneous work quickly disappears

- predict and pre-empt problems and questions

- deliver appropriate outcomes to the other person.

Look back at the two examples on the previous page. In each case, the individuals concerned were able to understand what they needed to do by understanding what ‘the other person’ wanted:

- The project team became focused on the outcome for the client.

- The analyst’s presentation was focused on building a simple message for the person who needed to see the presentation.

3 What are the minimum number of steps required to get there?

There are plenty of people who make things complicated. While some people cannot see the wood for the trees, others cannot even see the trees for all the branches, twigs and leaves. Effective managers have a knack of making things simple. Given the increasing time pressure on all managers, this is an essential skill to have. Discovering the minimum number of steps requires asking a few more questions:

- What is the desired outcome (again)?

- Are there any shortcuts: can I buy in a solution, get someone else to provide all or part of the solution; is there an authoriser who can short cut the normal approval channels?

- Does the 80/20 rule apply here: can I achieve 80 per cent of the result with just 20 per cent of the effort by focusing on the few customers who count, or the critical analysis that will really decide the issue, or by attacking the two big cost sinks that are causing the most problems?

- What are the critical dependencies? There is normally a logical order to events: billing comes after shipping comes after manufacturing comes after selling. Establishing this logical order breaks even the most daunting problem down into bite-sized chunks which people can manage.

4 What are the consequences of this course of action?

This question is about predicting risks, problems, unintended consequences and uncomfortable questions. If you can predict problems, you can pre-empt them. This is also the stage at which the manager may allow a little complexity to creep back into the course of action.

In theory, the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, except in non-Euclidean geometry. In practice, management find that the fastest route is often not a straight line. When you are sailing against the wind, the fastest route between two points is a zigzag. Sailing straight into the wind gets nowhere. This is an experience most managers understand after they have tried to sail against the political winds in their organisation.

The management mindset

- Start at the end

Focus on the outcome and the results you want to achieve. Be relentless, stay focused. - Work through others

Don’t try to be the lone hero. Management is about making things happen through other people. Learn to work through and with your peers, bosses and team members: influence, motivate, build trust and credibility. - Drive to action

Analysis shows you are smart; action shows you are effective. Do not look for the perfect answer: you will never find it. The perfect answer is the enemy of the practical answer. Find what works and do it. - Take responsibility

Don’t blame others and focus on the past. Focus on the future, action and results. You are responsible for the outcome, for your career, for your conduct and for your feelings. Make the most of it. - Be (selectively) unreasonable

When you accept excuses you accept failure. Stretch yourself and your team. Be inflexible about goals but highly flexible about how you get there. - Make a difference

Performance is not measured in emails and meetings: it is measured in outcomes. Show you are relevant to the agenda of bosses two or three levels further up: work on a high impact agenda. - Be proactive

Don’t wait to be told. If you see an opportunity or a problem, use it as a chance to shine: take ownership. Embrace ambiguity and crises as chances to grow, learn and make a difference. - Adapt

The rules of survival and success change by organisation and by level. Don’t become a prisoner of past success. Continually learn, grow and adapt to the new rules of survival and success in your new context. - Work hard, work smart

There are no shortcuts or magic formulas. It is hard work. But work smart: manage time effectively and efficiently; focus on the right things; work through others and do not try to do it all yourself. - Act the part

Be a role model to others in what you do, how you look and how you behave. Act as you would like your peers to behave. Set yourself high standards, and then keep raising them.

The easiest way to work out the consequences of most management actions is to understand who the major stakeholders are and how they will react: each stakeholder has a different perspective and will have different criteria and needs. The finance department will worry about affordability and payback; marketing will look at competitive reactions; sales will worry about price and positioning; HR will look at the staffing implications. Once you have a map of who is interested in what, you can then plot a zigzag through all the constituencies to make sure each one is able to satisfy their required needs.

2.2 Achieving results: performance and perceptions

Managers have to achieve results. Results are not always about delivering a profit: not everyone has P&L responsibility. Managers may be responsible for project outcomes, quality outcomes, costs, product design, development and delivery, and recruiting and training staff. There are endless possible results that managers may be responsible for. Ultimately, the test for a manager is to make sure they deliver those results. For better or for worse, many organisations do not look too closely at how results are achieved, unless there is immoral or illegal activity involved. Conversely, if a manager fails to deliver results, the manager fails. Results are better than excuses.

There are essentially five ways in which managers can achieve acceptable results:

- Work harder.

- Work smarter.

- Fix the baseline.

- Play the numbers game.

- Manage for results.

1 Work harder

This is an unpalatable truth in the era of work–life balance, which is shorthand for a wish to work less. This is also the 24/7 era, when we are permanently attached to various electronic tags which constrain us as much as a prisoner’s leg irons: there is no escape. Working harder, however, is not a lasting solution. Given the ambiguous nature of most managerial work, bosses do not know how much effort each manager is really putting in. If you achieve results, the assumption is that you can do more. So the reward of working harder is to get more work. You only get less work when you can no longer deliver or you complain loudly enough. Hard work is necessary, but it is not enough.

2 Work smarter

This is the desired outcome of results obsession: we find ways of doing things betterfastercheaper. Betterfastercheaper is the essence of capitalism. When a manager achieves betterfastercheaper the ideal result is promotion. The more immediate consequence is normally the same as working harder: an increased workload rather than decreased working time. Like working harder, working smarter is necessary but not enough.

3 Fix the baseline

Beating a soft target is easier than beating a tough target. Many managers realise that it is better to negotiate hard for one month securing a soft target than it is to work hard for 11 months trying to beat a tough target. Even CEOs do this: watch the frequency with which a new CEO discovers a black hole in the organisation’s finances which requires write-offs and adjustments to the corporate goals. Fixing the baseline does not enhance the prospects of the business, but it does enhance the prospects of your career.

4 Play the numbers game

There is an annual ritual in most organisations called ‘meet year-end budget’. Experienced managers know that this is coming, and they know that even if they are doing well, they are likely to be asked to deliver a little more in the last two months to make up for shortfalls elsewhere. This is where managers get creative. If they are doing well, they will hide spare budget for the inevitable year-end rainy day. If they are behind, they will use a combination of real actions on costs and whatever accounting smokescreens and mirrors can come to their support (see page 81 for more detail). This may appear cynical, but it is part of the reality of management survival.

The first four approaches all depend on the manager doing things. The role of the manager is to make things happen through other people. This leads to the fifth managerial option.

Unintended consequences of results obsession

Results focus has some unintended consequences. In the public sector, targets obsession leads to awkward outcomes, for instance:

- Schools are ranked on students’ test results: they enrol pupils for the easiest subjects in order to increase pass rates. They try to pre-select students on ability so their overall results look good. Results improve, education does not.

- Hospitals are asked to reduce waiting times for operations: they use creative methods to move people off waiting lists and on to other sorts of lists; they require re-registration at frequent intervals so that people disappear off the list when they fail to re-register.

- Government needs to spend but also to meet its debt targets: it moves both spending and borrowing off its records by letting the private sector undertake major infrastructure projects (relating to hospitals, railways, etc.). If the private sector tried the same techniques, the regulators would probably start calling.

The private sector is not much better. For instance:

- The first edition of this book before the financial crash noted that: ‘Banks reward loan officers on the volume of loans they make. Lending money to people is easy: getting it back is harder. By the time the bad debts mount up, the loan officers have received their bonus and moved on.’ The crash was inevitable. Another will happen because nothing has changed. Traders are rewarded for taking huge risks, but their downside is limited if they lose.

- Train companies and airlines extend the published flying time on routes (London to Paris is 20 minutes slower than 25 years ago), which allows them to claim more of their flights arrive on time.

- London Underground has reduced service frequency on the Circle Line to ‘improve customer satisfaction’. This means that it can meet its published, but reduced, targets for the service being available. Ultimately, if it runs just one train an hour, it can achieve near 100 per cent service compliance and 100 per cent customer dissatisfaction.

5 Manage for results

Managers make things happen through other people. There is a huge difference between doing (working harder and smarter) versus managing (enabling other people to work harder and smarter). Managers who try to do it all themselves are not really managing and, in the long run, are condemned to fail. Management is a team sport. You need to have the right people tackling the right challenges the right way: the focus of this book is on how you can make things happen through other people.

2.3 Making decisions: acquiring intuition fast

Decision making principles

Good managers are often referred to as being decisive. ‘Being decisive’ is one of those vague management terms like ‘professional’, ‘effective’ or ‘charismatic’ that is very difficult to pin down; no one can teach it and it is assumed that you either have it or you do not. We found that decisive managers typically show four specific behaviours:

- Bias for action over analysis. Actions achieve results, analysis does not. Less analysis can often lead to a better solution because it forces discussion to focus on the big issues that make a big difference. Often, detail derails decision making.

- Prefer practical to perfect solutions. Accept that the perfect solution does not exist. Find a solution which will work in practice, even if it is not perfect in theory. The perfect solution is the enemy of the good solution because the search for perfection leads to inaction. A good solution leads to action.

- Solve the problem with other people. Use the collective knowledge, wisdom and experience of the organisation to gain insight. Use it to identify and avoid the major risks and pitfalls. But do not convert a problem-solving process into a political negotiation in which the solution is a fix designed to pacify everyone. The result will be the least offensive rather than the most effective solution.

- Take responsibility. Where there are shared and unclear responsibilities, most organisations breathe a huge sigh of relief if you have the courage to step up and take responsibility. You become the person to follow. It is a defining moment which separates leaders from followers: most people will be very happy to follow you.

The behaviours described above are hallmarks of a decisive manager, at least on minor matters such as sorting out late deliveries, staffing problems, budget arguments. But these useful instincts often desert managers when they are faced with a major decision. As the scale of the problem escalates, the number of people involved in it grows and the rational and political risks increase. Suddenly, managers become very risk averse. The manager’s nightmare is to be held accountable for a decision which went wrong. To avoid this fate, managers seek refuge behind formal processes, exhaustive analysis and widespread consultation to optimise the decision and, more importantly, diffuse responsibility. Even if the decision turns out to be wrong, everyone has been so involved in the process that they will find it difficult to pin the blame on one person. What should be a rational process (make a decision) becomes a political process (avoid blame for a potentially damaging solution).

The larger the decision, the more risk averse managers become.

Managers are even more risk averse than the public. In general, the pay-off from making a risky and correct decision is quite low. Your success may be derailed by other factors or claimed by other people, and it will probably have a minimal impact on your overall pay and promotion prospects. But the consequences of making a risky but incorrect decision are huge: colleagues will make sure that the blame is pinned on you, and your reputation will suffer.

A risky exercise

You are offered the chance to win $1,000 on a toss of a coin (a 50/50 chance, in theory). How much would you pay to play this game?

Most people will offer much less than $500, which should be the mean average pay-out from the game, if it is played enough times. Fear of loss outweighs the prospect of gain. Of course, make the game for 10 cents, and most people will happily play for 5 cents: risk aversion increases with the scale of the possible loss.

Decision-making traps

Analysis over action

Analysis is safe, action is risky. But analysis often throws up more challenges and more problems which require more analysis. Slowly, the problem-solving exercise takes on a life of its own. No one can see through the thicket of challenges and problems which the analysis is throwing up. Paralysis through analysis becomes an unwelcome reality.

Seeking perfection over practicality

Faced with small problems, shortcuts seem acceptable. But bigger problems deserve better solutions, and the biggest problems deserve perfect solutions. The perfect solution must also be the least risky solution. Except that in the messy world of management, there is no perfect solution. Any solution tends to be a trade-off between two unacceptable alternatives. No good solution exists on paper: good solutions only exist in reality.

Hiding behind other people

It is far better to be wrong collectively than it is to be wrong individually: no one wants to run the risk of being asked to don the corporate equivalent of the dunce’s cap. In some organisations it is better to be wrong collectively than right individually: being right against the grain is seen to be disruptive to the team. The search for collective responsibility is natural risk avoidance. Collective responsibility requires consensus, which rarely represents the best solution. The consensus solution represents the least unacceptable solution to each constituency: it is a political fix. The purpose of involving other people is not to achieve a consensus, it is to gain insight. Ultimately, one person needs to own both the problem and the solution. They should use other people to gain insight and to drive action, not to hide behind in case things go wrong later.

Shedding responsibility

Responsibility for large problems, and their solutions, is often shared among several departments. This can lead to an unseemly game of ‘pass the blame’: no one really wants to be associated with causing the problem. Analysis of the problem becomes bogged down in an autopsy about what went wrong, rather than what the solution should be.

Decision making in practice

There are many decision-making and problem-solving tools available to managers and these are covered in the next chapter. In practice, managers rarely use such formal tools. Instead, there are three questions they ask themselves which normally yield a practical answer:

- Is there a pattern I recognise here?

- Who does this decision matter to, and why?

- Does someone know the answer anyway?

1 Is there a pattern I recognise here?

Pattern recognition is what managers often refer to as intuition or experience. Unlike intuition, however, pattern recognition can be learned. Pattern recognition is simply a matter of observing what works and what does not work in different situations. If you recognise a familiar pattern, you will be able to predict what actions will work or fail. You will appear to have intuitive business sense.

Learning to recognise patterns

Advertising is a curious world where the creativity of advertisers has to meet the disciplines of the marketplace. Good advertising can transform a brand; poor advertising can kill it. Either way, it costs a fortune to make and to air. The challenge for clients, who pay the advertising agencies, is to know whether their spending is going to work.

Procter & Gamble (P&G), one of the world’s largest advertisers, does not rely on intuition. It has built up huge experience and has learned patterns of success and failure. Young brand managers have to acquire this intuition, or pattern recognition, fast. Inside the major offices of P&G there is a dark room where the secrets of advertising intuition are learned. On appointment, the first thing a brand manager will do is to go into this room and acquire the knowledge. He or she will do this by reviewing tapes of all the advertising the brand has aired in perhaps the past 50 years. Watching 50 years of Daz advertising is like watching a social history of Britain. And for each piece of advertising, there are key statistics to show how well it fared.

After a few hours of watching such advertising, even the rawest marketing manager acquires an uncanny ability to look at 30 seconds of advertising and to predict how well it scored and performed. This is intuition acquisition at speed. It cuts through theory and shows what works in practice.

Pattern recognition comes into play when the manager realises that he or she is going to be responsible for making a decision. If it is a familiar pattern, it is normally an easy decision (see the box above for a typical example).

Effective managers observe and learn from everyday situations to build up their knowledge of what does and does not work in their own organisation. We may not have the luxury of reviewing 50 years of people managing conflicts, negotiating, influencing people or problem solving, but good observation builds our skills, helps our pattern recognition and helps us appear to have excellent business sense and intuition.

Pattern recognition can be acquired and learned in a range of decision-making conditions:

- Competitive reactions: long-established competitors know how one another will react, without the need for collusion which would break anti-trust laws. In many markets, there is a price leader from whom all competitors take their cues. If the leader raises prices, everyone else follows. If there is a temporary price reduction for a promotion, competitors ignore it. If the price reduction is permanent, competitors follow. This makes pricing decisions across companies very simple: it is called ‘follow my leader’.

- Buying decisions: Philip Green is a billionaire retail entrepreneur who owns several fashion chains in the UK. When he looks at a rack of clothing he is reputed to be able to cost each item accurately and to establish its proper retail price at a glance. The buyer who is perceived to have overpaid for any line items is likely to have an uncomfortable discussion with the boss. Green is able to do this because he has seen thousands of racks of clothing over several decades of retail experience. His expert judgement is based on piling up the experience. He can demonstrate intuitively good sense on buying matters because he has seen the purchasing patterns so many times before.

- Managing people, including bosses, is largely about pattern recognition. We quickly have to learn what turns people on and off in terms of working style, risk appetite, people versus task focus, process versus outcome focus and more. No pattern is the right pattern: from the manager’s perspective, the point is to learn what works with different people.

If a decision fits into a familiar pattern, then most managers have the confidence to make it. The P&G brand manager will approve the development of a new campaign based on judgement, without recourse to expensive and time-consuming market research. Green can buy effectively because he recognises the patterns unique to his trade.

2 Who does this decision matter to, and why?

Decision making is as much about politics as it is about reason. Managers need solutions which lead to action: the perfect solution which is not acted upon is useless. Decisions only lead to action if people support them. This means that managers will ask ‘who?’ as much as ‘what?’

There are essentially four possibilities here, each with a different outcome in terms of decision making:

- The decision is most important to a team member. If possible, back the team member. Coach them and encourage them to arrive at a decision. Do not let them become dependent on you for making all their decisions: they will not grow professionally and you will die under an avalanche of requests for decisions.

- The decision is important for one of your bosses. If you understand his or her agenda, it should be clear what the preferred decision is: frame the problem and the solution, and sell it to the boss. If the choice is unclear, work through the issue with the boss.

- The decision is important to another colleague. Long term, managers need alliances and supporters across an organisation, so talk to the colleague and find a mutually advantageous solution. Help them: win a friend.

- The decision is important to you and your agenda. If the choice is obvious, decide. If it is not, get help (see below).

This is decision making which is free of any problem-solving skills. The key skills are understanding the agendas of bosses, colleagues and your team, and framing the decision to support those agendas. For this reason, many decisions emerge gradually over time. A consensus slowly builds, small actions are taken which favour one choice over another and gradually a preferred course of action emerges. This fits with the apparently chaotic schedule of many managers: lots of small interactions over the day help them understand one anothers’ agendas, sell an agenda, gather information and migrate slowly towards a series of decisions.

3 Does someone know the answer anyway?

Management is a team sport. No single manager is expected to know all the answers, but they may be expected to find all the answers.

For more complex decisions, no one knows the answer. But many different individuals in finance, marketing, operations, IT, sales and HR will hold part of the answer. They each hold one piece of the jigsaw and the job of the manager is to put the pieces together. This is both an intellectual process (discovering the best answer) and a political process (building a coalition in support of the emerging answer). This can take time. It may require several iterations before consensus can emerge and all the different agendas can be aligned.

In Japan, this consensus-based decision making is called nemawashi. The idea is to build agreement to the decision before the decision-making meeting. Carry out the initial conversations in private. This is critical. As soon as anyone has taken a position in public, they will feel the need to defend it at all costs, rather than lose face by changing their position. In private, you can have much more open and flexible conversations: real issues can be discussed, agendas can be aligned and commitment can be built. The more you listen, the more you will understand the politics of the decision and the views of different stakeholders. You will gain more insight into the nature of the decision: you will better understand what the real challenge is, what the different options are and the consequences of each option. The more you listen, the more likely it is that a consensus will emerge around one preferred solution.

How to influence decisions

- Anchor the debate on your terms

Strike early; set the terms of the debate around your agenda. - Build your coalition

Manage disagreements in private; let people change their view without loss of face; publicise any agreements widely to build a bandwagon of support. Find powerful sponsors to endorse your position. - Build incremental agreement

Don’t scare people by asking for everything at once. Ask individuals to back the one part of your idea where they have relevant expertise (finance, health and safety, etc.). - Size the prize

Build a clear, logical case which shows the benefits of your proposed course of action; quantify the benefits and have them endorsed appropriately. - Frame the decision favourably

Align your agenda with the corporate agenda; frame your idea in the right language and style for each person; be relentlessly positive. - Restrict choice

Don’t give too many options: it will tend to confuse. Offer two or three choices at most. - Work risk and loss aversion to your favour

Show that alternatives to your idea are even riskier. - Put idleness to work

Make it easy for people to agree; remove any logistical or administrative hurdles for them. - Be persistent

Repetition works. What works? Repetition. Repetition works. The harder you practise, the luckier you get. Never give up. - Adjust to each individual

See the world through their eyes; respect their needs in terms of substance, style and format; build common cause; align your agendas.

The final decision-making meeting still has relevance, but it is not about making a decision. It is about confirming in public to all the stakeholders that there really is consensus and agreement. It builds confidence and legitimises the decision which has already been made in private.

2.4 Solving problems: prisons and frameworks – and tools

Problem solving is sometimes thought to be the preserve of people who are brains on sticks. In reality, brains on sticks are precisely the wrong sort of people for solving most management problems: clever people search fruitlessly for the non-existent perfect solution so they achieve nothing. A workable solution is preferable to the perfect solution because it leads to action. The perfect solution is the enemy of the practical solution.

Three principles lie behind effective problem solving:

- Know your problem

- Focus on causes, not symptoms

- Prioritise the problems.

Smart managers think they know all the answers. Really smart managers know the right questions. The best answer to the wrong question is useless. The purpose of this section is to help you identify the right problem, ask the right questions and arrive at a practical solution.

1 Know your problem

All students are given strict briefing before sitting any exam: ‘Make sure you answer the question.’ This is remarkably obvious advice, which is ignored remarkably often – with catastrophic consequences. The same advice needs to be given to all managers: ‘Make sure you answer the question.’ At least with school exams, the question is clear. In business, no one hands out an exam paper: you are expected to know what the exam question is without being told.

At junior levels of management, the exam questions are often pretty clear. They tend to be expressed as simple performance goals: sell more product, trade more profitably, bill more personal time. As managers continue their careers, clarity reduces and ambiguity increases. The goal may be clear (make your profit target) but the means to the end are not. It pays to fight the right battles the right way to achieve the overall goal. You have to know which are the right battles.

Know your problem

This was my big break. I got to present to the CEO. I gave what I thought was a brilliant presentation. At the end of it, the CEO coughed quietly and seemed to confirm my judgement of my own talents.

‘That was a very impressive presentation,’ he said. ‘I only have one question…’

I was ready for any question. I had 200 back-up pages of detailed analysis. This was my chance to shine.

‘What, precisely, was the problem you were solving?’ he asked.

That was the one question I was not ready for. I quickly vanished into a puff of my own vanity and confusion.

2 Focus on causes, not symptoms

No one would think of trying to cure chicken pox by using spot remover. But such confusion over symptoms and causes happens regularly in business. Many cost-cutting programmes fall into this trap. The CEO looks strong and effective announcing some target job cuts or cost savings. In highly macho form the message was conveyed to the CEO’s management team as: ‘Give me 20 per cent cost reduction and 20 per cent head count in 12 months, or you will be part of the 20 per cent. No excuses.’ Over 15 per cent was delivered and some top executives were fired. It took years for the business to recover from the mindless cost cutting of marketing (loss of market position and revenues), of R&D (loss of new product flow) and of talent (loss of morale).

Cost problems are always a symptom of something else, such as:

- inadequate revenues, which in turn may be a product problem, marketing and sales problem, distribution problem

- wrong product and customer mix, which are expensive to serve and do not pay enough to justify the cost

- ineffective processes and inefficient working practices.

The business goes in dramatically different directions if you choose to focus on increasing revenues, changing the product and customer mix or improving processes and working practices. Simple head count reduction will not achieve any of these positive outcomes.

At a smaller scale, many HR practices deal with symptoms, not causes. Performance-based appraisal and promotion systems sound highly dynamic. But they focus on symptoms (how well did the person do?) versus causes. Understanding the causes of good or poor performance is at least as important as measuring the outcome:

- Why did they do well or poorly?

- What skills need to grow to raise performance?

- What assignments will best suit this person in future?

- Are they building the right skills and experiences for their career and promotion prospects?

- How can performance be improved?

The skills-based approach to appraisal results in a better appraisal discussion. The good/bad performance appraisal can be confrontational and not very actionable. Many managers shy away from giving bad news, which helps no one. Focusing on causes (not skills) is more positive and actionable.

Anyone can spot a symptom of a problem. It does not take a genius to see that profits are not high enough. The mark of a good manager is one who can go beyond symptoms and unearth the root causes of the problem. There are no easy shortcuts available. But there is one simple principle – keep on asking one question: ‘Why?’

3 Prioritise the problems

Management is never short of problems and challenges. There are not enough hours in the day to solve them all. So managers have to be selective. Three simple questions help identify which problems are worth addressing:

- Is it important? Does this problem make a significant difference to achieving my overall goals? Put another way, if this problem is not resolved will it have a serious adverse effect? Is there a simple stop-gap solution which will prevent things getting worse while I concentrate on other problems?

- Is it urgent? Do today what you have to do today. Will the problem be worse tomorrow than it is today, and does it matter? If it does, act now. Can I buy time? Problems do not always become worse: time has a habit of throwing up more information, more opportunities and more potential solutions. It can also heal emotional upsets.

- Is it actionable? One of the dubious joys of management is to have to live with problems which you can do little or nothing about. You may be at the mercy of strategic challenges and decisions, IT projects going awry or competitive pressures forcing sudden and unexpected demands on you. Under these circumstances, the best thing to do is nothing. Focus on what you can control, not on what you cannot control.

Problem-solving tools

Most managers solve most problems intuitively. It is rare that managers sit down and do a formal problem analysis. But it helps to have a few tools and techniques at hand. You do not need to get pen and paper out every time you want to use them. It is enough to have the frameworks in your mind, and then you can use them to check and challenge your own thinking.

Here, we cover six classic problem-solving aids:

- Cost–benefit analysis

- SWOT analysis

- Field force analysis

- Multifactor/trade-off/grid analysis

- Fishbone/mind maps

- Creative problem solving.

No single way is the best way. They all have value in different contexts. The key is to pick the right approach for the right context. Typical assumptions for each approach are:

- Cost–benefit analysis. Assumes a well-defined problem and solution which needs to be evaluated financially for formal approval.

- SWOT analysis. Assumes a highly ambiguous, often strategic, challenge which needs further structuring.

- Field force analysis. Assumes a choice is to be made between two courses of action including non-financial and qualitative criteria.

- Multifactor/trade-off/grid analysis. Assumes a choice between multiple competing options with multiple criteria of varying importance.

- Fishbone/mind maps. Assumes that there is a problem where the root causes need to be identified and which needs to be broken down into bite-sized chunks.

- Creative problem solving. Assumes a highly complex problem to which there is no known answer and; for which, an original approach is required.

1 Cost–benefit analysis

This is the staple of all good management decision making. When it is not used, disaster often ensues. The disciplines of cost–benefit analysis are most commonly abused on IT system changes which are sold in on the basis of being ‘strategic’. When managers say ‘strategic’ they often mean ‘expensive’.

A strong cost–benefit analysis is highly compelling. It forces management to take a proposal seriously: no executive wants to turn down a credible proposal which is financially attractive. The key here is credibility. It is not enough to produce a financially attractive proposal. It has to be credible. There are three elements to making the proposal credible:

- Strong, logical reasoning.

- Validation of the numbers by the finance department: if it does not support the calculations, then you are dead meat. Involve finance early, get its advice and buy-in. Make sure you produce numbers to a format that finance recognises and can approve.

- Operational credibility. Venture capitalists look beyond the numbers to the people who are behind the numbers. They back people as much as they back ideas. Executives do the same. It pays to find highly credible supporters and backers for your proposal.

Each organisation will have its own way of looking at financial benefits. The most common are:

- payback period

- ROI (return on investment)

- NPV (net present value).

Of these three, payback is the simplest, but NPV is the most rigorous and is relatively easy. ROI is only included because it is widely used: in its simple form it is misleading and in its more refined form it is very complicated.

Payback period

How long will it take me to recoup my investment? One bank has a three-year payback period for staff redundancies. If it costs $100,000 to fire someone who costs the bank $50,000 a year including benefits, then the payback period is two years and it passes the three-year test, provided no replacement is hired.

ROI: return on investment

This is where things get sticky. There are many different ways of calculating ROI. Each expert will start climbing the wall and spitting blood if you do not use their pet method. So the advice is to work with your finance department and discover which rules it plays to. Enlist its support and, preferably, get it to do the calculation for you.

The problems start with knowing what the required rate of return should be. There are long and tedious debates about this which involve discussion of forecast and historic equity risk premiums, and one versus five year betas, and much more. We will avoid that debate for now. For most managers, the required ROI is mandated from above. It may vary according to the risk of the project: a cost-savings programme may have a required return of 10 per cent; expansion into a new market may have a required return of 15 per cent to adjust for the risk of the project. To do this analysis you need to know the cost of the investment and the net benefits it will produce over its lifetime, together with whatever rate of return you are required to achieve. A simple worked example, looking at the cost of installing AVR (automatic voice response) in a call centre to replace humans, follows.

Worked example (1)

The cost of the AVR machine is $1,000 today. It will cost $100 a year to maintain, but it will save $500 of labour, so the net annual benefit is $400. At the end of four years, it will be given away to charity: it will have no resale value.

The ROI calculation now looks like this:

The simplest form of ROI is as follows: ((Total benefits – total costs)/total costs) ∞ (100/number of years). In this case, the calculation would be:

![]()

This shows that this investment just meets the corporate goal of 15 per cent ROI.

This simple form of ROI is misleading. It assumes that a dollar today is worth as much as a dollar in four years’ time: the next section shows this is untrue. The alternative to this form of ROI allows for the different value of a dollar over time. It is called IRR (internal rate of return) and is effectively the ROI on an investment which results in an NPV of zero. This requires first understanding NPV, which is useful.

The most practical solution is to work with whatever rules your finance department has in place. The rules may be wrong and misleading, but if that is how decisions are made, then it makes sense to work to them.

NPV: net present value

This is perhaps the most orthodox and reliable form of cost–benefit analysis.

The one key concept here is the discount rate. This is a way of saying that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow: I can invest today’s dollar and make it worth $1.10 this time next year. And your promise of a dollar next year is much more risky than your offer of a dollar right now. Because of risk I will take less than one dollar (perhaps even 70 cents) right now instead of a promise of a dollar later. The discount rate adjusts for the time and risk effects of accepting a dollar later instead of a dollar now.

A 15 per cent discount rate implies that a dollar now is worth as much as a promise of $1.15 next year, $1.32 the year after and about $2 in five years’ time. To put it the other way round: if I am promised $2 in five years’ time, that is worth about $1 to me today. I apply a discount factor of 0.5 to the promise of a dollar in five years’ time.

This analysis also shows that the AVR is a worthwhile investment. But it is a very limited calculation because:

- It does not factor in major sensitivities and uncertainties (see below).

- It ignores second-order effects (disgruntled customers left hanging on the phone, and possibly switching supplier).

- It ignores alternatives (outsourcing or offshoring the call centre, upgrading the call centre to make it revenue generating through cross selling, segmenting the customers so that high-profit customers still get personal service, etc.).

Sensitivity analysis

This gets us into the land of ‘what if’, for which spreadsheets are a saviour. ‘What if’ calculations allow us to test our major assumptions. For instance, in the NPV example above, the AVR project becomes unattractive (it achieves a negative NPV) if:

- the required return is raised to 20 per cent

- the AVR needs to be replaced after three years, not four

- the net cost savings turn out to be $300 per year, not $400

- the AVR kit costs $1,200.

Managers quickly learn how to manipulate assumptions to ensure the right answer appears in the bottom right-hand corner of the spreadsheet.

In the most sophisticated world, different outcomes can be assigned different probabilities and a weighted NPV can be derived. Probability analysis is important in some industries: the profitability of financial leasing of computers depends heavily on resale values and likely depreciation rates; exploration for oil depends heavily on probabilities. But for most management decisions, decision making is much simpler. If a project only just scrapes past a cost–benefit analysis, it is probably not worth it: you know the numbers will have been fixed to pass the test and that reality is unlikely to be as rosy as the forecast. If a project is worthwhile, it tends to sail past any cost–benefit analysis with ease. If it underdelivers against forecast, it may still beat the required return for the organisation as a whole.

2 SWOT analysis

Not all problems succumb immediately to a cost–benefit analysis. Cost–benefit analysis implies a degree of certainty about outcomes. Managers know that the only true certainty is uncertainty. Putting some structure into ambiguous and uncertain situations helps decision making and problem solving. Perhaps the simplest way of structuring unstructured problems is a SWOT analysis. SWOT stands for:

Strengths

Weaknesses

Opportunities

Threats.

SWOT is a simple way of looking at strategic challenges. For instance, should Techmanics (a fictitious company) expand into China?

Strengths: Techmanics has some great technology and wonderful products which no one else can fully match. Strong R&D will keep us ahead of competition.

Weaknesses: No Chinese distribution, no Chinese staff who can understand the market.

Opportunities: Vast and growing market, especially in the luxury and gadget segment where Techmanics is focused. The high end of the market is highly profitable.

Threats. No intellectual property protection: Techmanics’ products may be ripped off. Death Star Ventures may enter China before we do and condemn us to being also-rans.

This highly simplified SWOT analysis shows:

- The value of structuring a difficult challenge: it gives a framework for further discussion.

- The value of exploring alternative perspectives: it looks at the costs and opportunities of expanding and not expanding into China, and at possible competitive reactions.

- The need to frame the issue before embarking on a detailed cost–benefit analysis.

3 Field force analysis

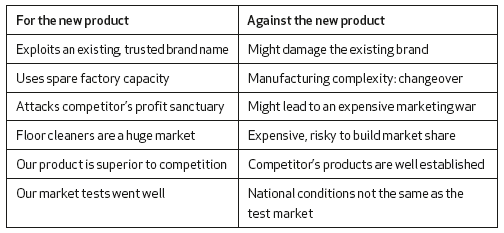

Field force analysis is a very fancy way of writing down the pros and cons, or the benefits and concerns of a specific decision. It is best used to evaluate a specific course of action where there are multiple, qualitative factors which affect the outcome. For instance, one company had a discussion about whether to introduce a floor cleaner based on a successful bathroom surface cleaner which already existed.

This simple analysis helps frame and focus the discussion. The ‘Against’ column becomes a risk and issue register. Standard problem-solving and brainstorming methods can be used to help resolve each of the risks and issues identified.

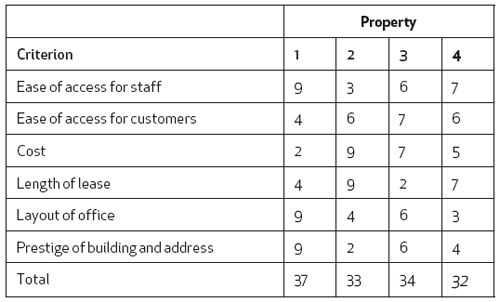

4 Multifactor/trade-off/grid analysis

This family of problem-solving analyses is a good way of making a choice between multiple, hard-to-compare options. The real value of this approach is that it forces people to think about the criteria they are using to make a decision. It forces them to be explicit about how important one criterion is relative to another. This cuts through many rambling debates where managers are arguing for different choices and are using compelling but competing arguments. All the arguments cancel each other out and result in a tense stalemate. This approach prevents the stalemate and leads to a much more productive discussion.

It has six simple steps:

- List the criteria for making the decision.

- Score each criterion for how important it is.

- List your options.

- Score each option against each criterion.

- Adjust the raw scores for the weightings you gave in step 2.

- Add the scores up and, hopefully, come to an agreed outcome: if not, at least you will know why, and where you disagree you can have a more focused discussion.

The following example looks at the choice of a new office.

Choosing a new office

Start with the unweighted scores out of ten.

The first cut seems to show that property 1 is a clear winner. At this point, the CEO steps in and points out that just as all executives are not equal, so all criterion are not equal. The CEO assigns weightings to the criteria with the following results, where the unweighted scores have simply been multiplied by the weightings assigned by the CEO:

The CEO is either fundamentally mean or is a diligent steward of shareholders’ money. Either way, costs dominate the weightings, so that property 1 falls from being first choice to last and property 2 becomes a clear winner, even though layout and access for staff look highly unattractive.

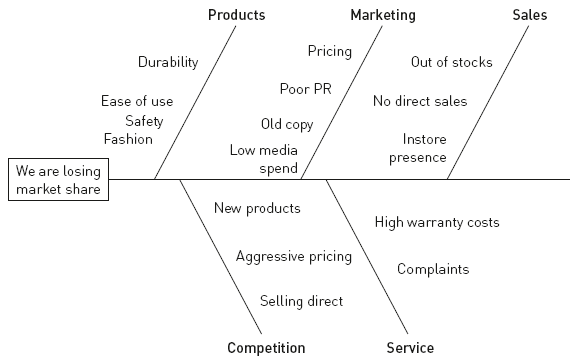

5 Fishbone/mind maps

This family of problem-solving techniques is another area which has been hijacked by experts. These techniques are useful for breaking a big problem down into bite-sized chunks. They are also a good way of discovering the root cause of a problem, as opposed to its symptoms. They are very visual exercises, which are often best done in small groups. The experts are very particular about making you use different colours for different parts of your diagram and can inflict an entire philosophy on your simple need to solve a problem.

For our purposes, we can keep it simple. The key steps are:

- State the problem (which appears as the head of the fish in the fishbone).

- Identify some of the major possible causes of the problem (the big bones of the fish).

- Drill down in each major area and identify specific issues to address or investigate further (the small bones in the fish). You can drill down even further on any of these items, if necessary.

A simplified example of a fishbone analysis is shown overleaf.

As a result of this brainstorming, you will have identified the major causes of the problem/symptom. If there is agreement about the root cause, move to action. Otherwise, you may need to do some more legwork to understand individual issues. Either way, you will have broken a big and messy problem down into manageable chunks, and you will have moved away from dealing with symptoms to dealing with root causes. These are two valuable outcomes, especially if achieved in a group setting where you build buy-in and commitment to the way forward.

Fishbone diagram

6 Creative problem solving

Not all problems can be solved by force of logic. The more interesting management challenges require a degree of creativity and invention. Asking managers to be creative will result in most of them breaking out in a cold sweat: creative workshops conjure up images of abysmal sessions where we all have to say what sort of tree/car/musician we would be if we were a tree/car/musician. Fortunately, there are some reliable ways of arriving at creative solutions without enduring the terminal embarrassment of a creativity workshop.

The simplest solution is to ask for help.

You may not know the solution, but others may. Even if they do not have the total solution, they can provide insights which may help you. There are plenty of exercises which demonstrate the power of the group to find a better solution than an individual can find. Desert, moon, space and island survival are all classic group dynamics exercises which prove the point. Type in ‘desert survival’ in any search engine and you will find plenty of helpful and free examples on the web.

The more formal solution is to ask for help in a structured way, through a problem-solving exercise. Here is a straightforward way to conduct the exercise in a series of steps:

- Agree who is the problem owner and what the problem is you need to solve. Try to make the problem as specific and as focused as possible. Also, try to express it as an outcome. General and negative problems are difficult to solve, such as ‘We are losing in the market.’ Define the problem more closely and positively. ‘How to increase retention rates among our most loyal customers’ is going to lead to more actionable and positive solutions than the more general and negative version of the problem statement.

- Outline the problem to a small group of people who between them have the knowledge, willingness and capability to provide insight and solutions. The ideal group has about four to seven people in it. Any fewer, and there are not enough to generate ideas and enthusiasm. Any more, and it becomes chaotic.

- Check for understanding of the problem statement, so that everyone is solving the same problem. Allow questions to check understanding, avoiding any evaluation of the problem.

- Generate ideas, and lots of them. Volume is good. Do not allow any evaluation of ideas at this stage. Get people to build on each other’s ideas. Get people to look at the problem from different angles (competitors, customers, channels, costs, products, service, etc.) to stimulate more ideas. One person records the ideas on a flipchart: this avoids too much duplication and lets contributors see that their ideas have been recognised so they do not feel the need to repeat themselves. Make things move fast: make people state the headline of their idea only. As with any good newspaper, the headline should encapsulate the whole story. This makes it easier to record.

- Select a few ideas to work on in detail. You can permit an outbreak of democracy at this stage. Give each person three votes, using Chicago rules. Chicago rules mean that there are no rules: they can split their votes, sell their votes, steal votes or consolidate their votes. Do not get hung up on process. If two people had similar ideas, let them consolidate them into one: do not have a big debate, just let the owners of the two ideas decide if they want to merge. You will normally find that there is consensus around three to five workable ideas, and you will have done no evaluation of them so far.

- Evaluate the most popular idea. Start by looking at why it is a good idea: evaluate its benefits. Managerial instinct is to look at problems first. The problem with problem focus is that it can kill good ideas. Once you understand why an idea is good, you can start to explore some of the concerns it raises. Express the concerns in an action-focused manner: ‘How to fund the idea’ leads to action, whereas ‘That is far too expensive’ leads to conflict. How you state the concern leads to radically different outcomes.

- If the solution you are all most excited about has some significant concerns attached, work through each of those concerns using the same process, starting at step 1 again. You will find yourself breaking the problem down into ever more manageable bite-sized chunks which you can deal with.

Problem solving for managers

- Find the right problem

The right answer to the wrong problem is wrong. Focus on causes, not symptoms. Understand why the problem has arisen. - Find the problem owner

Find out who owns the problem and why it matters to them. They may already know the answer, so ask them. Establish how important and urgent it is and gauge your response accordingly. - Use your experience

You have expertise and experience in your role: use it. If you have seen this sort of problem before, you should know what to do. So do it. - Ask

If you are unsure what the best solution is, ask for advice. Your peers may have the answer, although they may all have different answers. - Avoid the perfect solution

The perfect answer is the enemy of the practical answer, because you will never find the perfect answer. Find what works and do that. - Stay future focused

Do not dwell on the past or try to apportion blame. Look to the future, look to action. - Focus on benefits before concerns

It is easier to spot risks than opportunities. But if you focus on the risks of every solution you will be paralysed by fear. Focus on the benefits first: if the benefits are big enough, then it is worth dealing with the risks. - Build a coalition in support of your solution

Asking for advice has the virtue of building consensus and paving the way for your solution to be put into action. - Keep it simple

Don’t boil the ocean of facts and analysis. Use formal problem-solving techniques sparingly: they are an aid to thinking, not a substitute for thinking. The best solutions are discovered through action, not designed through analysis. - Drive to action

There is no such thing as a good idea which never happened. A solution is only good if it happens. A partial solution is often enough: you can then build on that and improve it.

2.5 Strategic thinking: floors, romantics and the classics

If you listen to business school professors, strategy is so sophisticated and complicated that only they can really understand it. To prove their point, they come up with all sorts of clever concepts such as value innovation, strategic intent, core competences and co-creation. These are supported by matrices, grids and charts which give the appearance of analytical rigour.

Do not be deceived. Most strategic concepts are:

- selective rewriting of history of some successful companies

- better at describing the past than predicting the future

- based on a few simple truths.

Most corporate strategy is formulated the same way as most corporate budgets: last year’s budget and strategy is the best predictor of next year’s budget and strategy. Both will change, incrementally. But few companies actually change strategy significantly. The exceptions are famous, but exceptional. WPP, the world’s largest advertising conglomerate, was formed out of a shell company which made shopping trolleys. Nokia, the world’s largest maker of mobile phones, had its origins in rubber (largest shoe factory in Europe), plastics (floor coverings) and forestry products.

Because most businesses do not change strategy fundamentally, the demand for deep strategic thinking from managers is not high. Nevertheless, it helps to understand strategic thinking, so:

- Understand the strategic relevance of your own activities.

- Know how to think strategically.

- Play the strategy game.

- Understand the nature of strategy.

If you can do these four things, you are well prepared for the executive suite.

1 Understand the strategic relevance of your own activities

I started to doubt the use of the word ‘strategy’ when the office manager started talking about strategic deployment of office space. I retired to the canteen to consider how I might strategically deploy my Brussels sprouts. As ever, the office manager was right and I was left to eat cold Brussels sprouts.

The office manager was answering the one strategic question which all managers have to be able to answer: ‘How can my actions and decisions support the goals of the organisation?’ At the risk of stating the obvious, this requires more than simply understanding the goals you have been set in your annual plan: it requires understanding the goals of the senior leadership team. Many managers fail this obvious test: they are so consumed with meeting their immediate goals that they forget to think about the broader context in which they are operating.

The office manager had a strategic challenge all of his own. As we walked round the office we could see lots of consultants working in individual glass fish bowls: these were meant to combine privacy with open communication. In practice, the walls stopped communication and the glass prevented privacy. The manager had heard the CEO talk about the need for teamwork, transparency and focus on clients: that meant working at the client site, not in our cosy offices. The manager thought it through, and came up with a radically new design.

Out went all the mini-palaces which were also known as partners’ offices. Instead, we were invited to share a common partners’ room: we were being asked to walk the talk on teamwork. Quite a few partners exploded with indignant rage: they were the idle ones who would be most exposed in a common office. Next step were the consultants. Out went their goldfish bowls and their desks. In came rows of hot desks. There were not enough to go round, so consultants suddenly found it more congenial to work at the client site. In came lots of small meeting places so that teams could meet and work together.

The office manager had grasped the nature of strategy: he had understood the needs of the organisation and taken action to support them. He had no need to understand grand corporate strategy, or to talk the language of core competencies. They were irrelevant. Managers do not need to be great strategists to think and act strategically: they need to understand the real needs of the organisation and to support those needs in their areas.

A simple test for strategic activity is this: will these actions get noticed at executive committee level? If they are relevant at that level, you are probably acting on matters which have strategic relevance. If not, you may still be making a useful but less visible contribution.

2 Know how to think strategically

The best strategic thinking is very simple. Clever people make things complicated. Really clever people make things simple. Many of the most successful organisations have very simple strategies:

- easyJet and Southwest Airlines: low-cost flying

- Dell: sell direct and make to order

- FedEx: overnight delivery, guaranteed.

Although they are very simple strategies, they are competitively devastating. Let us look at each in more detail to see why:

- easyJet and Southwest Airlines: low-cost flying. By starting with a zero cost base, and avoiding all the frills and complexity of full-service airlines, they achieved cost per mile and fares which the full-service airlines cannot reach with their legacy costs and infrastructure. They created clear competitive distance against the incumbents.

- Dell: sell direct and make to order. This eliminated all the sales forecasting problems, unsold stocks, cash-flow crises and fire sales that dogged the traditional model of selling through resellers. Incumbents felt unable to abandon their loyal resellers and were stuck.

- FedEx: overnight delivery, guaranteed. No one else did it at the time. Creating the nationwide infrastructure and building volume and scale fast made it hard for anyone to follow.

Now consider how much these strategies have changed over the past 20 years. Each organisation has essentially the same strategic formula as 20 years ago. Great strategies rarely change.

3 Play the strategy game

If you ever apply to join a strategy consulting firm, you will get a chance to play the strategy game, also known as the case method interview. It is worth practising this game: it gives insight into the prospects of your employer and enables you to hold your own in discussions with senior executives.

The ostensible purpose of the game is to find an answer to some imponderable business question such as: ‘Should MegaBucks expand its product range from photography to other imaging products like copiers?’ The real purpose of the game is to show that you can think in a structured and strategic manner: the actual answer is unimportant. Cynics might say that it is the essence of strategy consulting: show you are smart and do not worry too much about the answer.

To succeed, you do not need to know the right answer. You need to know the right questions. An effective strategy discussion will look at the issue from a series of different angles:

- What capabilities do we have? This gets at the core competence arguments of Hamel and Prahalad (management thinkers and academics). Imaging and photographic technology are close to each other, as Canon discovered by bridging both markets.

- What are the market prospects? Is it growing? Is it profitable? What are the pricing trends? Critically, you need to look at individual segments of the market. Which ones are underserved? What needs are unmet? Canon identified that the old central copying function, focused on high volume, did not meet the needs of secretaries who needed just one or two quick copies locally. There was an unmet need for quick, cheap and average-quality copies. High speed was not important.

- What does the competition look like? Again, look for underserved market segments. Xerox was huge and looked unbeatable. But it had no product for distributed/local copying across the office.

- What are the economics of the market from a customer perspective? Instead of being tied into long leases for big copiers, secretaries would be happy to buy cheap local copiers.

- What are the economics from the manufacturer’s perspective? The big money is in the replacement toner. This means the key is to get the copier on to the secretary’s desk, if necessary at a loss, and then make money on the supplies. This then implies that the product must be simple to maintain and resupply, without the need for a technician. This in turn leads to a distribution model which is more mass market, accessed via resellers rather than through the traditional model of B2B salesmen working on commission.

As you go through the game, you should keep in mind a checklist of questions and perspectives you need to cover:

- Capabilities.

- Market prospects, by segment – size, growth, profitability and cyclicality.

- Customer needs, by segment – remember product, price, positioning questions.

- Competitive position, by segment. What is our value proposition? Do we have any sustainable advantage, barriers to entry?

- Economics, relative to competition, the customer and us. What are the effects of scale across the value chain? What is the value chain?

Keep asking these questions until you find convincing answers. Quite often you will find that just one critical insight develops out of all the questions. In the exotic world of wet cement supply, the economics of distribution favour the creation of a series of local monopolies. It takes some questioning to get to that simple outcome. Asking the set questions will quickly help you identify why Microsoft is highly profitable, whereas airlines are, at best, cyclical in terms of profitability.

4 Understand the nature of strategy

It helps to know the language of strategy. Strategy is spoken in two very different languages: the classical and the postmodern.

Classical strategy

Classical strategy is a world of cause and effect. It is a search for the business equivalent of Newton’s laws: ‘If x happens, then y is the result.’ It is strategy in the true tradition of the Enlightenment: finding universal rules to apply to all situations. The godfathers of this world are Michael Porter (Five Forces analysis) and the Boston Consulting Group (responsible for matrix mania). The good news is that these formulas shed light, and provide some insight, into complex situations.

The bad news about formulaic strategy is that it is extremely dangerous. If everyone uses the same tools and the same analysis, they come up with the same answers. This leads to the lemming syndrome: ‘10,000 lemmings cannot be wrong, so I will jump off a cliff as well…’ The dotcom bomb was a classic lemming moment. UK telcos all did the same analysis and bid £22.4 billion for 3G licences: they are unlikely ever to get that money back. When many of the world’s banks decided to chase profits by lending to the sub-prime markets, creating complex derivatives and increasing their capital leverage, they were possibly smart individual decisions. Collectively they built a house of cards which fell down and led to global recession. Following the herd can be very dangerous.

Postmodern strategy

This is the language of a group of professors who all learned their trade from C.K. Prahalad (core competence, strategic intent). His acolytes include Gary Hamel, Chan Kim (value innovation) and Venkat Ramaswamy (co-creation). They are rebels against classical orthodoxy. For them, strategy is a process of discovery in which you create the future, rather than react to the present by analysing the past. This is a process-driven view of strategy much more than an analytical view of strategy. It does not pretend to have all the answers: it challenges organisations to discover and create answers for themselves.

The good news about this approach is that it leads to much more creative outcomes and engages the organisation more deeply. The bad news is that it is often not practical. It seeks radical strategic change, but most large organisations either do not need radical redirection, or are not capable of achieving it.

On balance, the classical approach to strategy suits established firms best. New entrants and start-ups use the postmodern approach, but are too small to realise that they are doing so.

2.6 Financial skills