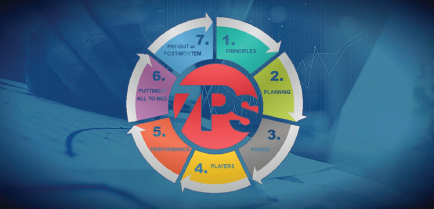

The entrance strategy is actually more important than the exit strategy.

—Businessman, Edward Lampert

This chapter will demonstrate clearly that, as in all walks of life, if you fail to plan, you plan to fail.

Thoroughly Plan Your Strategy

Thorough preparation and planning give you the best opportunity to understand all the possible strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats in your deal game plan. Do not be tempted to cut corners here. Despite the temptation to do so, never rush your planning.

All successful deals begin with the right strategy, with risk analysis and measured processes in place. The tactical benefits of a well-honed strategy are that it helps you determine what you want, how you are most likely to achieve it and then to choose your optimal tools and optimal team for execution.

Speed, of course, can be important at the right time in the deal-closing proceedings, but advanced planning, clarification, and preparation are even more important. Being prepared increases your ability to successfully get through difficulties on the deal journey with confidence. It is important to complete your preparations in advance as there may be limited time to stop and regroup when you are in the thick of a deal.

Ask the Right Questions to Get the Right Answers

In my experience, the more open and authentic you are in your questioning, the more you are likely to receive the quality of the information you require.

—Thomas Wedgwood (of Waterford Wedgwood fame),

Former Partner, Trestle Group and Foundation

The use of direct questions is the time-honored way of gathering information from people willing to share it, but the questioning needs to be done in a careful, measured, thoughtful way.

Face-to-face questioning also gives you the invaluable opportunity to pick up on the hints, gestures, suggestions, and other subtleties that accompany the response. After all, the whole point of asking questions is to help you explore and frame your “deal zone” (see below) for the deal and, in the process, to find out what the other side needs and wants.

I cannot overstate the importance of taking your time to suitably frame your questions. Quality answers require quality questions. Poor questions almost always result in unclear, unhelpful, vague, and time-wasting answers. Also, you will be amazed at how much confidential or sensitive information you can elicit from the other side—if you ask the right questions.

When I was a commercial lawyer, working as head of legal for Europe, Middle East, and Africa for a U.S. technology multinational, twice I was tasked with unblocking major technology supply deals with separate world-renowned European technology companies. Both deals had been blocked for many months. I decided to make site visits to these customers to determine what was causing the blockages and to find a pathway to getting the deals consummated. On-site, I used these simple tactics:

• Once you have gathered sufficient information, asking “closed” questions that required a “Yes” or “No” answer;

• Using simple, direct, uncluttered language (it wasn’t always easy as a lawyer to do this!);

• Giving the other side space in terms of time to answer, repeating the question if necessary;

• Waiting for the other side to answer my questions rather than being tempted to elaborate, expand, explain, clarify, justify, or worse still, look away, to fill the awkward silences;

• Maintaining as much eye contact with the opposing team members as possible, particularly during the pivotal moments when I was asking questions and receiving answers;

• Thanking the other side for each answer provided before moving onto the next question;

• Avoiding being interrogative or argumentative if the other side chose not to answer or deflected the question back at me (for all sorts of reasons, some of which included confidentiality, trade secrets, and so on);

• Being culturally astute—for example, working with the rituals and nuances at play and particularly when it came to small talk during deal discussions. You should be attuned to appropriate cultural protocols to use these to your advantage at various stages of the deal journey.

I am pleased to say that these tactics helped me to quickly find the blockages, determine what was needed to generate forward movement and, ultimately, to unblock both deals.

You won’t always be successful in eliciting the information you need from the other side—on a first try or, indeed, even after several attempts. In my experience, the other side may not answer if:

• They believe there are justifiable reasons of confidentiality, commercial or trade secrecy, or privacy (a non-disclosure agreement may be a solution here);

• They simply are not sure which information is important or relevant to provide (it’s your job to make this clear to them, to avoid this situation occurring);

• They don’t trust you. Perhaps they sense—or worse, have reason to believe—that your intentions are not honorable, or that you have distorted or withheld information from them.

When giving information yourself, there are a couple of important things to bear in mind:

• Never lie or fabricate information. The truth usually comes out in the end and your business reputation must always be paramount. However, do not assume the other side is not lying just because you have decided that you will not. You must probe information provided by the other side and conduct your due diligence to ensure you get as close as possible to establishing the other side’s true intentions.

• Knowing which information to disclose and which to withhold requires experience, usually earned by trial and error. If you are uncomfortable (for good reason), try to avoid disclosing the information. But if you are simply trying to avoid disclosing for unjustified reasons, you will be (rightly) regarded as being obstructive or unhelpful and this will definitely not encourage the other side to be open with you (which might damage your bargaining position at a later time).

As the U.S. technology multinational lawyer, two deals that I was tasked with working on had been blocked for many months. I decided to make site visits to these customers to determine what was causing the blockages and to find a pathway to getting the deals consummated. Given what had transpired, I was confronted by a reluctance to discuss what had caused the impasse.

Have you experienced this?

What did you do?

What did I do?

To move things along, on-site with both the clients and U.S.-based parent company, I used the simple tactic of direct, authentic face-toface questioning to build a picture of what had transpired and to then frame a strategy to move things along.

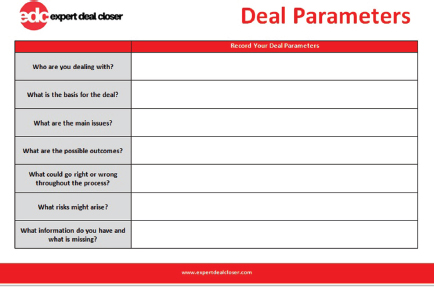

Establish the Parameters of the Deal Landscape

From a business perspective, direction-setting in relation to a deal—whether merger and acquisition, take-over or otherwise—is essential. It is critical to lay the foundations, but deal-closers should not choose generic methods to achieve their objectives. Different industries, company categories, sizes, business models, and so on all require distinct and customized approaches. Nonetheless, you must be clear on:

• Who you are dealing with;

• What is the basis for the deal;

• What are the main issues;

• What are the possible outcomes;

• What could go right or wrong throughout the process;

• What risks might arise—and when;

• What information you have and what is missing.

Sample Deal Parameters Chart

Only a fool would enter into a deal scenario not knowing who was on the other side, anticipating their communication style, which points to make, what the value of the exchange is to both sides, and so on. Success in deal-closing all comes down to preparation and planning.

Be Aware of Deal Location and Dynamics

There is no “one-size fits all” method for striking a deal. Similarly, there is no single best location for deal-closing. You may meet in your office, the other side’s office, or on neutral ground. It can be a good idea to ask the other side where they would like to meet—if nothing else than to guage their attitude.

You usually have more control over the substance, pace, and direction of a deal discussion if it takes place on your home turf. But this is not always the case.

Generally, I find less formal settings are more conducive to small talk and thus to effective deal-closing. For example, in many countries, there is a culture of “doing business” in cafés, reflecting perhaps a more laid-back approach that leads to “good natured” business discussions. I conduct a significant amount of deal-related business in cafés, especially at the earlier, less formal, stages of a deal.

Culture and context determine the extent to which small talk is a valuable tool in the deal-closing process. You should always be attuned to what is said and, as importantly, not said. The best deal-closers are constantly alert to clues and triggers, such as how are people sitting, where are they looking, how are they looking, are drinks ordered at the start or later in the process, and so on.

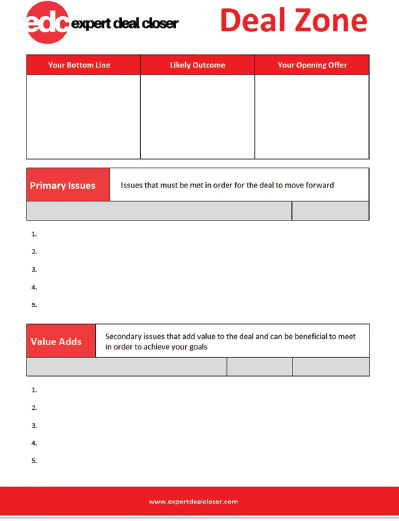

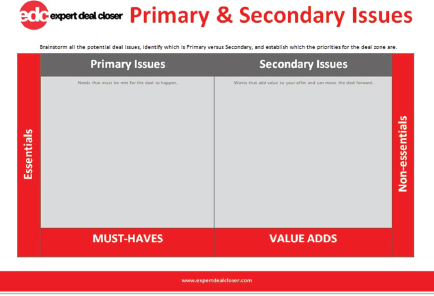

Identify the Primary and Secondary Issues at Play

As part of your planning and preparation phase, it is essential to decide your key issues and priorities—for example, what your opening position and bottom line (see below) need to be and how and when to make the first move. Only then can you realistically prepare your arguments and proposals.

That said, you should resist the temptation of getting so fixated on achieving one issue that you lose sight of the relative, or potential, importance of other issues at play. Deal-closing requires an appreciation of what is important now, plus the ability to predict what will be important down the line and to balance the two.

It is essential not to rush the first step of identifying and prioritizing all relevant issues. There are essentially two types of issue at play:

• Primary issues: including location, size of deal, price, and so on;

• Secondary issues: the “nice to haves” but not essentials.

Unlike primary issues, secondary issues are rarely deal-breakers, but they can be particularly useful if there is an impasse at primary issue stage. Introducing secondary issues can add sufficient perceived—or even actual—value in the eyes of the other side to get the deal moving again. In other words, trading the secondary issues may be the means of providing both sides with the complete result they need from the deal, which they might not otherwise have appreciated.

Sample Primary and Secondary Issues Chart

Distinguish Personal Wants and Business Needs

What you need and what you want aren’t the same things.

—Author, Cherise Sinclair

Generally speaking, primary issues equate to needs and secondary issues to wants. A good deal-closer is able to tell the difference between personal wants and business needs, which can be important given that the latter usually must be your priority when seeking to strike a deal.

Results are most likely to be achieved in a deal where there is a business need.

—Jeremy Balius, Managing Director of OM Three Sixty

Need is usually determined by what drives the business environment. For example, the opportunity to grow and prosper is an obvious positive driver of a deal. Things become a little blurred, however, when each side views the anticipated deal trajectory in different terms. Here a good deal-closer would do all that’s necessary to align the deal to maximize the growth opportunities presented.

Negative factors include threats, weakness, and problems. Counter-intuitively perhaps, I find that there is nothing better than a negative push to focus the mind on a corporate deal. Nobody wants to live with negativity, so the impetus to do a deal to move out of that environment focuses minds.

While the definition, and perception, of a need can differ from person to person, it is essential to have a strategy to address the need. Use your value proposition to persuade the other side that their need(s) will be satisfied by the deal.

Develop Your Deal Zone

Once you have worked out your primary and secondary issues, you are ready to enter what I have called the “deal zone.” In doing so, you must be aware that deal-closing rarely goes exactly to plan at all stages. So, just because you are organized and have categorized your issues does not mean that the other side will be able to, or even want to, differentiate between the two types of issues—and postponement or deadlock may result. Some things are just outside your control.

Before you move forward, you should check whether you have all the information that you could possibly obtain at this point and address any gaps in your knowledge. The key to the deal-closer in any deal getting what he or she wants is to provide the other side with the value they are looking for. So, you need to focus on what the other side values from their primary and secondary issues (but where the cost to you is minimized), rather than conceding too many of your own primary issues.

Developing your deal zone is really about determining how the issues at play are valued by each side and identifying the zone in which a potential deal is possible. Never assume that what is important to you is of equal importance to the other side. Never rush determining your deal zone—take time to ensure it is realistic.

To define your deal zone, you need to research, prepare, and stress-test the following positions (in order) for each of your primary (and some secondary) issues:

• Likely outcome: This is your realistic target to achieve;

• Bottom line: This is your absolute worst-case position at which you will walk away from the deal;

• Opening position: This is the best possible position you think you might achieve. Again, it needs to be based in reality, as you don’t want to jeopardize the deal with an outlandish opening position.

The key outcome of defining your deal zone is to enable you to eventually land somewhere between your opening and likely outcomes. Be aware, however, that framing the deal zone is not a static process; rather, it is a fluid two-way process that changes and develops throughout the deal discussions.

So, as seen, the deal zone is where you set your limits by determining the likely outcome, bottom line, and opening positions for each primary (and some secondary) issue. For example, you want to obtain something for $10 but feel that you may be asked to pay $11.25, and you can’t afford more than $11. In this situation, your bottom line is $11, your opening position may be $9.75 and your likely outcome may be $10.50.

Summary

• Thoroughly plan your strategy.

• Ask the right questions to get the right answers.

• Establish the parameters of the deal landscape.

• Be aware of deal location and dynamics.

• Identify the primary and secondary issues at play.

• Distinguish personal wants and business needs.

• Develop your deal zone.

Dermot Mannion

How important is it to ask the right questions to get the right answers and what can go wrong if you do not ask the right questions?

Answer:

The important thing here is, there’s no such thing as a wrong question. In negotiations, people will often try to bombard you with technical terms gobbledygook, frankly. Never be afraid to stop the negotiations and say, “Look, I’m sorry, I just haven’t understood what you’ve said. Please explain it in plain English.” So, really, the key message here is, there’s no such thing as a dumb question in negotiations. If it’s on your mind, put it out there.

Jeff Caselden

Tell me about a time when you were able to leverage secondary issues into your favor to bring about a deal.

Answer:

Part of how this whole deal came about was through a collision of many secondary issues. While our client was generally happy enough with the product solution of ours that they were leveraging for their use, we were facing secondary issues on a few fronts so our product was constantly evolving well beyond the legacy product that our customer was reliant upon. We wanted to kill it to focus on a single product code base to make our own lives simpler going forward.

We were also trying to develop an external cloud based offering that we could actually offer as a commodity product. And lastly, we were undergoing a technical evolution within the company where everyone was moving to the cloud and away from the old ways in which we built and deployed our services. Our client was ultimately going to face a lot of the same challenges themselves, so we were able to get them to initially agree to being part of our experiment to kill all of these birds with one stone, if you will. In a sense, we were kind of offering them their own “get out of jail free” card for the technical hurdles they’d also have to resource and work through, which we were going to solve for them. I’d imagine to them it sounded like a win-win situation, they would end up with something that was cheaper, that was a more flexible option, that was a more performing product, and they’d actually get someone else to do most of the work for them.

Kingsley Aikins

Tell me about a time when you were able to leverage secondary issues into your favor to bring about a deal.

Well, you know, in the business I was working in, it was an interesting business. It was kind of a left side of the brain and the right side of the brain business. I mean, the left side of the brain wants budgets and analysis and technical issues, and the right side of the brain kind of wants purpose and meaning and all that kind of stuff, softer sort of stuff. And I found that you need to have both of those, they were the things that went together. But interestingly enough, the left side of the brain allows you to make decisions, but the right side of the brain allows you to do stuff. And I found that was an interesting kind of combination of primary and secondary sort of influences, to try and get that balance right. You know when facts come up against emotions, emotions always win. And I think we have seen that with Brexit and the election of Trump in the United States emotion always wins.

1. What are the tactical benefits of a well-honed strategy?

It helps you determine what you want, how you are most likely to achieve it, and then to choose your optimal tools and optimal team for execution.

2. Why is face-to-face questioning so important in the deal-closing process?

Face-to-face questioning gives you the invaluable opportunity to pick up on the hints, gestures, suggestions, and other subtleties that accompany the response. After all, the whole point of asking questions is to help you explore and frame your “deal zone” for the deal and, in the process, to find out what the other side needs and wants.

3. What would you be foolish to enter into a deal scenario without?

Not knowing who is on the other side, anticipating their communication style, which points to make, what the value of the exchange is to both sides, and so on. Success in deal-making all comes down to preparation and planning.

4. What is the difference between primary and secondary issues?

Primary issues equate to needs and secondary issues to wants. A good deal-closer is able to tell the difference between personal wants and business needs, which can be important given that the latter usually must be your priority when seeking to strike a deal.

5. What are the three positions in deal-closing?

• Likely outcome: This is your realistic target to achieve;

• Bottom line: This is your absolute worst-case position at which you will walk away from the deal;

• Opening position: This is the best possible position you think you might achieve. Again, it needs to be based in reality, as you don’t want to jeopardize the deal with an outlandish opening position.