CHAPTER 10

Developing Accountability in Risk Management

The British Columbia Lottery Corporation Case Study

JACQUETTA C. M. GOY

Director of Risk Management Services, Thompson Rivers University, Canada and Former Senior Manager, Risk Advisory Services, British Columbia Lottery Corporation

This case study describes how enterprise risk management (ERM) has developed over the past 10 years at British Columbia Lottery Corporation (BCLC), a Canadian crown corporation offering lottery, casino, and online gambling. BCLC's enterprise risk management program has been developed over time through a combination of internal experiential learning and the application of specialist advice. The program's success has been due to the dedication of a number of key individuals, the support of senior leadership, and the participation of BCLC employees.

The approach to ERM has evolved from informal conversations supported by an external assessment, through a period of high-level corporate focus supported by a dedicated group of champions using voting technology, to an embedded approach, where risk assessment is incorporated into both operational practice and planning for the future using a variety of approaches depending on the context.

BACKGROUND

BCLC is a crown corporation operating in British Columbia (BC), Canada. The corporation was established by act of the British Columbia legislature in 1985. As a commercial crown corporation, BCLC is wholly owned by the province but operates at arm's length from government, enjoying operational autonomy while reporting to the minister responsible for gaming, currently the Finance Minister. All profits generated by BCLC go directly to the provincial government. The initial remit of the corporation was to operate the lottery schemes previously administered for British Columbia by the Western Canada Lottery Corporation. In 1997, BCLC was given responsibility to conduct and manage slot machines, and in 1998 the corporation's remit broadened again with additional responsibilities for table games in casinos. In 2004 an online service, PlayNow (www.playnow.com), was launched.

BCLC has been a highly successful organization for over 28 years, delivering over $15.7 billion in net income to the province of British Columbia. Through April 2012 to March 2013 more than $1 billion in gambling proceeds helped fund health care, education, and community programs in British Columbia (BCLC Annual Service Plan Report 2012/2013). BCLC operates the provincial lottery and instant games and provides national lottery games through the Interprovincial Lottery Corporation. Across the province, BCLC manages 17 casinos (15 casinos plus two casinos at racetracks), 19 community gaming centers, and six bingo halls through a number of private-sector service providers. PlayNow, BCLC's legal online gambling website, offers lottery, sports, bingo, slot, and table games, including online poker. BCLC employs about 850 corporate staff with more than 37,000 direct and indirect workers employed in British Columbia in gambling operations, government agencies, charities, and support services.

BCLC's mandate is to “conduct and manage gambling in a socially responsible manner for the benefit of British Columbians” with a vision that “gambling is widely embraced as exceptional entertainment through innovation in design, technology, social responsibility, and customer understanding.” The organization holds the following values as key to its success:

- Integrity: The games we offer and the ways we conduct business are fair, honest, and trustworthy.

- Social Responsibility: Everything we do is done with consideration of its impact on and for the people and communities of British Columbia.

- Respect: We value and respect our players, service providers, and each other.

BCLC believes that playing fairly is a serious responsibility and an empowering opportunity. A commitment to social, economic, and environmental responsibility is central to everything the organization undertakes, and is reflected in the BCLC slogan, “Playing it right.” BCLC strives to create outstanding gambling experiences with games evolving with the player's idea of excitement. For BCLC, playing is not all about winning; it's about entertainment.

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE RISK MANAGEMENT JOURNEY

BCLC began its enterprise risk management journey in 2003 with the initiation of an Enterprise-wide Risk & Opportunity Management (EROM) initiative. The impetus for the initiative was twofold—the 2002 inclusion of risk management in the British Columbia Treasury Board's Core Policy and Procedures Manual and BCLC's head of Audit Services championing the need for enterprise risk management (ERM).

As a first step, an external consulting firm was contracted to undertake an enterprise-wide risk assessment and to support the Internal Audit team in developing the skills and resources to manage the new ERM program. Interviews and facilitated workshops at management and executive levels were conducted, a risk dictionary was constructed, and the highest risks were identified. The assessment focused on inherent risk compared with an evaluation of management effectiveness to produce a gap analysis, and there was also a discussion around risk tolerance. A final report was produced (Deloitte and Touche 2003), and advice was also provided on potential next steps for the program.

Although the EROM initiative was well received, financial constraints put a hold on the subsequent business case. As a result, the plan to take the program forward through the appointment of a dedicated risk manager and funding for training of a number of risk champions was not implemented at that time.

LEARNING FROM THE FIRST ERM INITIATIVE

The initial assessment provided a strong starting point for the BCLC ERM program, but even though the engagement was originally intended to be the first part of a longer-term initiative, there was insufficient impetus to put the program into operation in the face of competing priorities. This is not an unusual outcome, as although using a consultant to kick-start programs can leverage experience and expertise that organizations may not otherwise have access to, using an external party contracted for a defined period of time can also lead to a project type approach, where the focus is more on getting the risk assessment completed and less on longer-term implementation. In addition, it may be easier to source short-term consultancy fees than it is to obtain longer-term resourcing commitments.

Another issue can arise where consultants bring in defined methodologies that do not easily fit with the organization's normal approach to decision making or where participants do not understand the underlying process, and so do not fully endorse and own the outcome. To overcome this issue, the consultants worked closely with the BCLC Internal Audit team with part of the stated purpose of the engagement being to build risk management expertise within BCLC.

RESTARTING THE PROGRAM―2006–2008

In early 2006, the head of Audit Services' proposal to update the 2003 risk assessment was endorsed by BCLC's executive team. Audit Services facilitated an assessment of critical strategic and operational risks facing BCLC, by developing a set of risks for analysis through consultation with the executive team, preparing an environmental scan, and concluding with a facilitated risk workshop to evaluate and prioritize each risk. The initiative was strongly informed by the successful ERM program being run at that time by another Canadian lottery organization, the Atlantic Lottery Corporation.

The intended outcome of the 2006 assessment was to inform the three-year-old audit plan, to develop new risk criteria, and to raise awareness about the importance of risk management. The success of the exercise led to the development and acceptance of a business case in August 2006 to resource a part-time risk manager, responsible for putting into operation the risk management program. This approach was endorsed by the CEO as part of an organization-wide initiative to develop and embed a high-performance culture across BCLC.

Leadership for the initiative was assigned to an executive sponsor. In the first instance, this was the chief information officer.

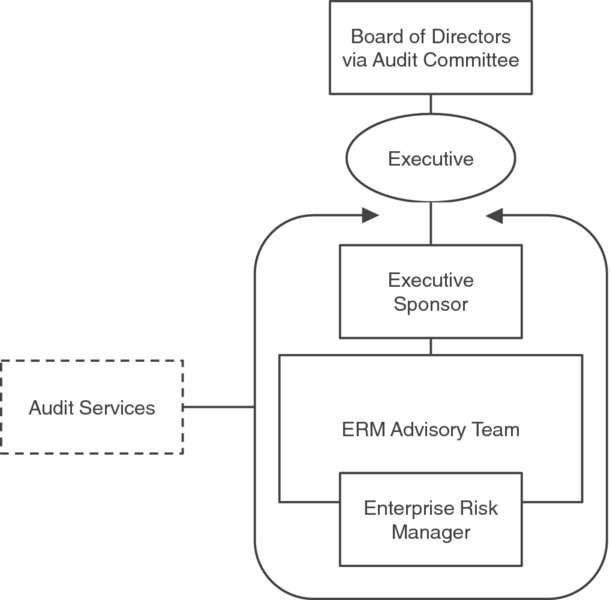

A cross-functional leadership team model was also approved, to be known as the ERM Advisory Team, responsible for oversight and approval of recommendations on behalf of the Executive Committee and consisting of the executive sponsor and a small number of key directors from each BCLC division. Operational support was provided by Internal Audit. The organizational structure is shown in Exhibit 10.1.

Exhibit 10.1 2006 ERM Organizational Structure

It is not entirely clear why the 2006 risk assessment exercise led to support for an ongoing ERM program while the 2003 initiative did not. The head of Internal Audit championed both initiatives, and the earlier risk assessment activity was well received. The consultants reporting in 2003 stated that “the culture in BCLC is proactive and is ideally suited to the EROM's philosophy and benefits.” Executive response to both initiatives was largely positive. There does not appear to have been a so-called burning platform created in 2006; it was more a growing recognition that the time was right to adopt a more formal approach to ERM. It may be that increasing recognition of the importance of managing risk across North America with the introduction of Sarbanes-Oxley requirements1 and publication of COSO's ERM Integrated Framework in 2004 influenced senior management. Or it could be that the simple iterative approach adopted by the head of Internal Audit when he decided to update the 2003 risk assessment—”Start slow and at the top, get learning and feedback, and then take down the ladder”—demystified the concept and increased engagement. Regardless, 2006 marked a new start for ERM, and the genesis of the current BCLC program.

KEY STEPS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ERM PROGRAM

For the second risk assessment, a streamlined process was adopted. Rather than starting with the risk statements from the dictionary, each VP was simply asked to identify their top three strategic and operational risks, with the results analyzed, combined, and allocated into the 2006 categories.

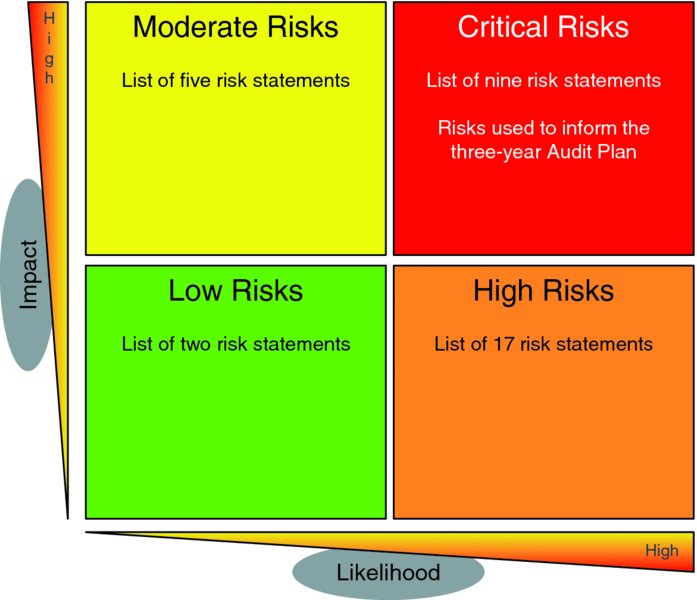

The resulting 37 risks were brought to two executive-level workshops and, as with the 2003 assessment, voting technology was used for prioritization. Nine critical risks were identified and taken forward to be integrated into the audit plan. One key difference from the 2003 assessment was the development of BCLC-specific likelihood and consequence qualitative criteria. Of interest is the correlation between the two assessments, with only two critical risks identified in 2003 not appearing in the critical zone in 2006, and no new critical risks introduced.

With the appointment of a dedicated Enterprise Risk Manager and the support of an executive sponsor, the launch of a formal ERM program became possible. The senior auditor from the Internal Audit team moved to the new position, bringing continuity with previous ERM initiatives. Between August and December 2006, the focus was on developing the core risk documentation, including terms of reference for the new steering group, an ERM policy, a project charter, and an initial plan. The initial areas of focus were to:

- Develop and continuously refine a practical ERM framework to support the identification and management of risk.

- Continuously manage risks, limiting exposure to an acceptable level while maximizing business opportunities.

- Embed a risk awareness that is a key component of instilling a high-performance culture.

A key feature of the new approach to ERM was the formation of the ERM Advisory Committee (known as ERMAC). The concept of ERMAC was to create risk champions, high-performing senior leaders from each division whose role would be to influence, communicate, and educate management and staff within their business areas about the benefits of risk management.

By January 2007, the new committee was established and the ERM policies and plan were in place, with proposals to embed risk management into project planning, business cases, and strategic planning under discussion.

In May 2007 a critical report about BCLC was issued by the British Columbia Ombudsman following an investigation into BCLC's prize payout processes (BC Ombudsman 2007). The investigation was triggered by a CBC Fifth Estate investigation2 in October 2006 on issues in Ontario associated with lottery retailers winning major prizes, with the concern being that similar issues could have occurred in British Columbia. Although no incidents of wrongdoing were discovered during the investigation, the report and a subsequent audit and recommendations published by Deloitte & Touche in October 2007 marked a critical point in BCLC's transformation into a modern player-centric organization.

For risk management, the Ombudsman's review led to both a greater impetus and a broader focus for the program. BCLC had always considered integrity to be vital to the organization, but the fundamental goal of delivering revenue to government was often the dominant concern, and this was reflected in earlier risk assessments. With the advent of the Player First program,3 significant additional resources and oversight were now dedicated to security, compliance, and reputation management, and this increased emphasis was reflected in the risk assessment conducted by the ERMAC team in April 2007.

The basis of the assessment was the risk statements completed by the Executive Committee in 2006, with new key risks facing BCLC added through consultation with key members of each of the business/support units and incorporated into an expanded risk dictionary. Once the new risk statement descriptions were agreed on, workshops were held to assess the risk ratings, and also to determine how effective were current arrangements for managing each risk. The 12 risks with the largest gaps identified between risk rating and management effectiveness were then selected for further profiling and control analysis.

Throughout 2007, the remaining enterprise risks were profiled in order to better identify the associated causes and controls. Two further enterprise risk assessments were facilitated in 2008, and a regular quarterly risk report produced from June 2008 forward provided details of both the development of the overall program and monitoring of individual risks.

Parallel to the enterprise risk assessment, a project risk assessment approach was developed and implemented, with a number of initiatives used to facilitate risk assessments, very similar to those conducted at an enterprise level. As with the enterprise risk assessments, the risk dictionary was used to support the development of potential risk statements, which were then voted on at a facilitated meeting of the core project team. Project risk assessments were piloted with four projects in 2007, and further developed with seven project risk assessments facilitated in 2008. Although the workshops were generally felt to be productive and beneficial, the volume of risks generated meant that on occasion it was not possible to assess all the risks presented.

In May 2008, the Enterprise Risk Manager was appointed director of Audit Services. Although risk assessments continued to be supported by the Internal Audit team, the further development of enterprise risk management was constrained due to the lack of dedicated resources, as the ERM manager post was not immediately filled.

REVITALIZING THE ERM PROGRAM—2009–2010

In the fall of 2008 the position of Manager, Risk Planning and Mitigation was created and an experienced risk manager was recruited to the position in late December 2008. The original intention of the appointment was to increase focus on risk treatment strategies and business-unit-level risk management activities, with the expectation that Internal Audit would continue to develop and report on the enterprise risk management framework. In late January 2009, the director of Audit Services left BCLC and the manager of Risk Planning and Mitigation assumed responsibility for managing all aspects of the ERM program.

The new risk manager brought a more operational approach, and was able to build on the excellent foundations already established to develop a new ERM strategy and supporting plan designed to move the ERM program to the next stage of maturity.

Throughout 2009, BCLC transitioned from the previous approach, where a portfolio of enterprise risk statements was assessed at a corporate level by ERMAC members, to a specific risk register with risks evaluated and agreed on at a divisional level and significant risks then escalated to the enterprise register.

One of the first changes was to move from an assessment of inherent risk with a supplementary assessment as to whether the risk was thought to be managed effectively to the use of a residual risk assessment methodology that included a more formal assessment of the effectiveness of control mechanisms in place. The next enterprise risk assessment was conducted in March 2009, and moved from the ERMAC voting approach to assessments by individual risk owners, with the committee providing more of a quality assurance function. New risk criteria were also adopted. A significant outcome was that the majority of risks were rated at a lower impact/consequence level (18 out of 29 dropping at least one rating, and three falling from critical to low risk).

Between March and July 2009, a series of risk and controls assessments workshops were held covering all divisions. The workshops brought together either functional teams or collections of specialists in thematic sessions (for example, marketing). Close to 300 managers and staff were involved. Each group attended two workshops; the first featured an educational component, brainstorming exercises, and process mapping with threats and vulnerabilities identification, while the follow-up session looked at a number of prioritized areas of risk in more detail, with a deep-dive assessment of risks and controls. The output of the workshops was the creation of divisional risk registers. Enterprise-level risks were then extracted from the divisional registers for an organization-wide view of all significant risks.

By September 2009, risk registers were established for all divisions. The new registers were more comprehensive than the previous risk documentation, with a greater focus on risk treatment and specific individuals identified as responsible for each risk treatment plan. The risk management policy was updated and new supporting guidance published.

Through 2009 and 2010, the risk management approach was further developed and embedded. In particular, the use of risk management in business case development and project management increased, while the new registers were updated on a quarterly basis. Regular quarterly reports on the risk management program were produced for discussion by the Executive Committee and at the Audit Committee.

In the summer of 2010, the risk management policy and guidelines were updated and a new risk management strategy was produced to reflect the newly published international standard on risk management, ISO 31000:2009, Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines. BCLC had previously been using the Australian risk management standard (AS/NZS 4360:2004), so the move to the new standard was a simple transition. At the same time, the government of British Columbia endorsed the new standard across all ministries, and subsequently used the approach for a number of provincially coordinated risk management activities (for example, planning for the 2010 Winter Olympics and preparing for a potential pandemic). The policy stated: “BCLC is committed to building increased awareness and a shared responsibility for risk management at all levels of the organization, and to facilitate the integration of the management and prioritization of risks into planning and operational activities.”

The terms of reference for the ERMAC were also updated (see Exhibit 10.2), reflecting the change in practice from a single central risk assessment to the more devolved approach now in place.

| January 2007–March 2010 | March 2010–March 2011 |

|

|

Exhibit 10.2 Terms of Reference for the Enterprise Risk Management Advisory Committee

STRENGTHENING THE PROGRAM—2010–2013

In 2010, it was agreed that Internal Audit should conduct a review of the risk management program with a view to “identify any gaps and areas for improvement to ensure that the fundamental building blocks are in place to deliver on the organization's risk management needs effectively and efficiently.” Interviews were conducted with Enterprise Risk Management Advisory Committee members, the executive team, CEO, and board and Audit Committee members.

The review found that the ERM process was well established and documented, with strong levels of support from all levels of the organization and an increasingly risk-conscious culture. However, risk management was not yet fully embedded within all of the organization's functions. There was some variance in perceptions of risk tolerance, and in general the program was stronger on reporting risks than it was at driving change, with significant amounts of informal risk-related discussions taking place outside of the program. Senior management also reported that too many risks were escalated to them, often at a level that was perceived to be too granular or operational.

In addition to the internal review, BCLC took part in a benchmarking exercise conducted by Ernst & Young together with seven other Canadian lottery and gaming organizations. The exercise consisted of a questionnaire completed by key risk personnel at each organization facilitated by telephone interviews conducted by the E&Y team.

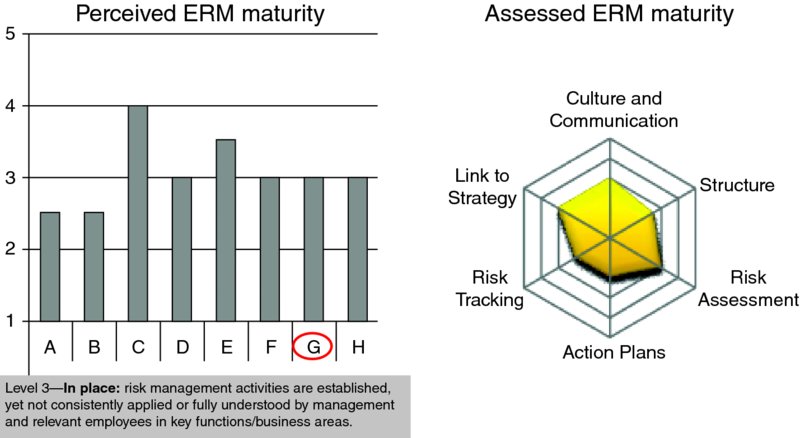

The results (Ernst & Young 2010) showed that BCLC was in a similar position to many of the other gaming organizations in having a relatively young ERM program. In common with much of the gaming industry at the time, BCLC's strongest area was risk assessment, while risk tracking and the ERM structure were relatively weak (see Exhibit 10.3). The exercise included a simple self-assessment of perceived ERM maturity, where BCLC assessed itself as having risk activities in place, but that risk management was not yet consistently applied and well understood by management and employees across the organization.

Exhibit 10.3 ERM Maturity at BCLC in 2010

Extracted from Ernst & Young ERM Benchmarking Survey, 2010.

The results of the internal review and the E&Y assessment were presented to BCLC's executive team in February 2011. A number of recommendations were proposed and adopted, including strengthening senior management ownership and accountability, realigning risk criteria to better match the BCLC's tolerance for risk across organizational objectives, and broadening the focus of the program from largely operational to a more strategic level.

In April 2011, the risk management function moved to the Finance and Corporate Services division, with the CFO taking responsibility for executive leadership of the program. The risk criteria and evaluation matrix were updated and the risk review process strengthened, establishing regular review meetings for every division whereby each division's senior management team reported to their vice president (VP) on their risks every quarter. Risk oversight was also reviewed, and in addition to strengthening processes at a divisional level, dedicated time at executive meetings was scheduled to review the quarterly risk report prior to presentation to the Audit Committee. A key step in increasing accountability came from the formal assignment of each area of high risk to the appropriate VP, who would be responsible for reporting each risk in detail and providing a regular update on progress with the agreed treatment plans.

At this time, the ERM Advisory Committee was disbanded. While the committee of risk champions had played a significant role in coordinating initial assessment activities and in increasing the understanding of risk management across the organization in the early years of the risk management program, it was now felt that as all directors were expected to be fully conversant with risk management and with the movement of risk identification, evaluation, and reporting into mainstream management, the group no longer added significant value.

A new Risk Management Planning Group reporting to the CFO was established to align and coordinate a number of risk and compliance activities, in particular looking for synergies between the risk, business continuity, insurance, and antifraud programs. The intention of the group was to assist in the design of tools and approaches that deliver progress across the programs and also reduce managerial overload from potentially competing programs.

Over the next year, a series of risk reviews were undertaken with each division, with the aim to refresh the divisional registers and to make sure that each group reviewed both current and potential risks against both BCLC and divisional strategies. The format of the reviews varied across groups, dependent on divisional responsiveness and parallel activities. Several workshops were held with broader management teams, two were jointly coordinated with Internal Audit exercises, and one was externally facilitated. The review process further increased ownership and accountability by reinforcing the message that risk management and reporting are the responsibility of everyone throughout the organization.

In early 2012 BCLC invited an external consulting firm to look again at its ERM program, consider the progress made since the work in 2003, and make some recommendations as to next steps. In April 2012, the consultants delivered a presentation to the board on “Moving from a Risk Monitoring Organization to a Risk Intelligent Organization,” and facilitated a discussion on risk governance and oversight. It was agreed to move risk oversight from the Audit Committee to the full board, to include more formal consideration of risk in the strategic planning process, and to continue to improve risk management processes, practices, and awareness.

In the winter of 2012 an opportunity arose to embed ERM into strategic planning when an exercise to identify and assess strategic risks was undertaken. The aim of this exercise was to identify and prioritize a set of holistic enterprise-level longer-term risks in order to inform strategic planning alongside a program of optimization. An off-site workshop was led by the CEO and the executive team with additional input from a small group of directors known as the leadership team, and supported by risk, corporate strategy, and audit services. Facilitation was provided by an external party. During the workshop, political, regulatory, economic, competitive, technology, and social business environmental factors were considered, and after a lively and informed discussion 11 key strategic risks were identified and initial sponsors assigned.

Following the workshop, a series of meetings were held with the assigned VP leads and other relevant parties, facilitated by the Senior Manager, Risk Advisory to discuss each risk in greater detail and using a bow tie approach,4 identifying key causes, consequences, controls, and planned treatments. A formal report was developed, and a strategic risk register is now in place. Going forward, the strategic risks will be used to inform strategic planning and business optimization, while the shorter-term, more operationally focused risks continue to be reflected and addressed in business planning at an enterprise, divisional, and initiative level.

BUILDING THE RISK PROFILE

One of the first steps often taken by many organizations in developing enterprise risk management is to identify the risks that the organization faces, although ISO 31000 recommends that the risk framework is established prior to this step and that the context is established prior to risk identification. For BCLC's first risk identification exercise, the context was provided by the consultancy team in the form of a risk dictionary or universe. The idea behind the risk universe concept is that all potential risks can be identified and classified into definitive categories, which can then be used as a generic tool to identify risk within and across organizations in a consistent manner.

The universe used for the initial BCLC risk assessment contained 70 generic descriptions of risks, which were adapted after consultation to fit the BCLC environment more accurately. The resulting 2003 BCLC risk universe included 59 potential risks divided into external and internal categories with strategic, operations, technology, financial, and organizational health subcategories, and can be seen in Exhibit 10.4. Each risk was given both a two- or three-word title and a short high-level description.

| External Risks | |||

| Competitor

Catastrophic Loss Financial Markets |

Legal

Regulatory Player Demands & Satisfaction |

Economic, Political & Societal Change

Industry |

Technological Innovation |

| Internal Risks | |||

| Strategic

Environmental Scan External Relations Business Portfolio Performance Measurement |

Mergers & Acquisitions

Alignment Organizational Structure Business Model |

Culture

Governance Strategic Alliance |

|

| Operations

Capacity Fraud Communication Extended Enterprise Vendor Management Health & Safety Change Management Environmental |

Compliance Customer Satisfaction Brand Name Reputation Pricing Product Development Safeguarding of Assets Business Interruption |

Supply Chain Product/Service Failure Knowledge Management Project Planning Performance Gap Gaming Integrity |

|

| Organizational Health | Technology | Financial | |

| Recruitment

Training & Development Employee Satisfaction |

Access, Security, & Tech. Integrity

Information Availability |

Credit

Market Liquidity |

|

| Ethics & Values Accountability & Responsibility Leadership

Retention, Recruitment, & Succession Planning |

Technology Infrastructure | Budget & Planning Valuation

Capital Acquisition & Management Financial & Management Reporting |

|

Exhibit 10.4 The 2003 BCLC Risk Universe

Some risk practitioners consider that the development and use of a risk universe or defined classification system is essential in any enterprise risk management program (Society of Actuaries 2009, 2010). However, to be effective there must be clear rules to support consistent classification, and each set of risks must consist of like items that are relevant to management decision making.

One common issue is that the list of risk statements may contain a mix of risk events, root causes, and outcomes, leading to imprecision and confusion, which may make assessing the level of risk or determining appropriate treatment more difficult. Another issue is that risk statements may be expressed in very generic terms that may not easily apply to the organization in question, or may make contributors feel that the risk assessment exercise is academic and not directly related to their day-to-day experiences.

The 2003 BCCL risk dictionary exhibited both of these issues, as can be shown in Exhibit 10.5.

| Example | Statement Type | Issue |

| Catastrophic loss risk—A major disaster threatens BCLC's ability to sustain its operations and minimize financial losses. | Outcome | The outcome could arise from a variety of different circumstances, making risk response problematic. |

| Governance risk—BCLC does not have the appropriate governance practices in place. | Cause | It is unclear why practices might be a cause for concern, making assessing the level of risk difficult. |

| Health and safety risk—Failure to provide a safe working environment for its workers exposes the organization to compensation liabilities, loss of business reputation, and other costs. | Risk | This is a clear problem and outcome statement but is expressed generically, which may mean that there is a poor fit to the organization. |

Exhibit 10.5 Analysis of Sample Statements from the 2003 BCLC Risk Dictionary

The intention behind the development of the risk dictionary was to provide common categorizations for specific risks identified across BCLC, and it was used effectively at a business unit level both to stimulate conversation and to identify specific risks, which were then translated to draft risk registers. At the enterprise level, the high-level statements were used for evaluation, and specific risk statements were not created.

The BCLC risk dictionary was reviewed, updated, and expanded in 2007 following the risk assessment exercise conducted by the Enterprise Risk Manager and the ERMAC team. One hundred and nine risk statements were captured in the categories of external, process, strategic, information, human capital, integrity, technical, and financial.

Through 2007 and 2008, the risk dictionary was used as the basis for assessments at an enterprise level, and the prioritized enterprise risks were then used to structure project risk assessments and also increasingly to support risk assessments in business cases.

In late 2008, as part of the ongoing development of corporate performance management, BCLC completed an exercise to implement the balanced scorecard methodology. This approach greatly assisted the risk management program in taking a fresh look into the corporate risk profile, and all of the risks were aligned to the new balanced goals. As a result, the risk dictionary was retired, with new guidance issued in 2009 recommending that all risk assessments start not from a predetermined list, but instead by looking at the objectives of the enterprise and, where relevant, the specific initiative.

The BCLC risk register generally includes around 100 risks across the nine divisions. As spreadsheets are currently used to manage the risk information, a decision was made to remove green (low) risks where it is determined that the risk level is stable and provided that there are sufficient monitoring processes embedded into mainstream management. Each quarter, a small number of new risks are identified and an equally small number are retired as circumstances change, awareness increases, and treatment plans come to fruition.

BCLC pays particular emphasis to the construction of clear descriptions for each risk, with the following guidance provided to all employees:

It is of particular importance that all risks are clearly expressed. BCLC has adopted a “CCC” approach where all risk statements should include not only the potential change but also the most significant consequence and cause. Risk statements should start with wording equivalent to “The risk of/that” or “The opportunity to” and be expressed as a possibility (using “may” or “might”). Descriptions should be limited in length and specialized jargon or acronyms should be avoided where possible, so that anyone reading the risk statement can easily understand the risk. Care should be taken in order to avoid alarmist language. When recording particularly sensitive risks, advice should be sought from either Risk Advisory Services or the Legal Services team.

—BCLC Risk Management Guidelines, 2013

On a regular basis, the Enterprise Risk Manager assesses the full set of risks and develops thematic risk maps, cascading from organizational goals and relating to key corporate strategies (the template schematic is shown in Exhibit 10.6). These maps have been used as a key input to risk review workshops and are incorporated into quarterly reporting processes. The advantage to this fluid approach is that the maps are easily modified as organizational focus has evolved; however, at present production is reliant on the insight and capacity of the Enterprise Risk Manager. BCLC is currently exploring purchasing a specialist ERM software support solution to more efficiently manage the program. Automated risk interdependency mapping is a function that the administrators hope to be able to purchase.

Exhibit 10.6 Thematic Risk Map Schematic

THE ROLE OF RISK MANAGERS, CHAMPIONS, AND COMMITTEES

BCLC's risk management program would not have been possible without the two risk managers, the ERMAC group and its champions, and the initial drive from the head of Internal Audit to implement ERM. Although most risk managers will state that the most important prerequisite for a successful risk management program is active endorsement by senior management, the provision of operational managerial resources is also essential. At BCLC, as with most organizations, the greatest progress has been made when there has been a designated risk manager assigned to the ERM program.

The role of the central risk function at BCLC, Risk Advisory Services, has not been to manage any specific risks, but rather to provide expert facilitation, coordination, and advice to management. The accountability for individual risks remains with the manager responsible for the program where the risk originates.

The two managers who have supported the ERM program came from very different backgrounds and brought different approaches to the program. Initially the program was initiated within Internal Audit and the first risk manager brought both extensive internal audit experience and, as an internal appointment, an understanding of BCLC's culture and approach. The second risk manager came with a more operationally focused risk management background and from a very different sector. Enterprise risk management is a developing discipline, and practitioners come from a wide variety of backgrounds (including finance, audit, health and safety, quality assurance, engineering, insurance, etc.), each with their own slightly different approach. Where risk management programs are supported by a single individual, change in personnel can be an opportunity to revitalize programs but also has the potential for discontinuity.

During the initial establishment of the program in 2007–2008, the active engagement of the ERMAC group of risk champions supported adoption of risk management across BCLC, bringing their knowledge and enthusiasm to both the enterprise risk assessments and the development of the program as a whole.

Risk champions are frequently advocated as a way to embed risk management into functional areas through their existing personal and professional relationships, and also as a group with diverse backgrounds and operational experience to assist with articulating a more holistic enterprise-level view of risk. However, there are some issues with the concept:

- Those selected may be the usual suspects—individuals who are chosen for every initiative either because they are felt to be particularly capable, in which case they may be overly stretched, or conversely because they are underutilized at present, leading to the possibility that they may not have the required influence to be effective.

- There may be a perception that the champion is responsible for risks in his or her division or functional area, even though other individuals hold the appropriate managerial or oversight role. This issue may lead to risks being identified but not effectively managed with formal treatment plans, and potentially to difficulties with monitoring and follow-up. Over time, champions may feel that they are put in a difficult position, or may become frustrated that their concerns are not taken forward and acted upon.

During the establishment of the ERM program, the role of the champions on the ERM Advisory Committee was clear, but as the program progressed, and in particular following the changes in 2009, the mandate became less clear and members began to feel a degree of frustration. The 2010 Internal Audit ERM review picked up on these concerns, and a new model was proposed that led to the disbanding of the committee in 2011.

The new model recognized the high level of engagement of senior management across BCLC and the more dynamic role of the Executive and the board, and also picked up on the developing concept of linking governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) matters into an integrated approach. The previous mandates of both ERMAC and a compliance committee that BCLC had established in early 2010 were brought together into the new Risk Management Planning Group (see Exhibit 10.7). This group consists of the leads from key BCLC programs, such as business planning, portfolio management, business continuity, enterprise architecture, internal audit, and policy management, with the primary role to share knowledge and improve coordination across the functions.

Exhibit 10.7 ERM Governance Structure, 2012–2013

Early accomplishments for the group included the development and adoption of a shared lexicon of key risk management terms, and a jointly developed compliance management proposal and business case. Currently, the group is focused on developing a broad-based GRC-type dashboard, which will bring together information about the status of risks, audits, policies, regulations, performance indicators, incidents, and issues at a divisional level.

DEVELOPING A MORE SOPHISTICATED APPROACH TO RISK ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION

According to ISO 31000, an essential part of developing any risk management framework is defining the criteria for evaluating risk. Risk criteria are used to reduce subjectivity and to communicate risk tolerance, and should lead to consistency across different assessments. In common with many nonfinancial organizations, BCLC uses risk tables with qualitative descriptions of a variety of potential impacts.

Over the past 10 years, a variety of risk tables and evaluation approaches have been adopted.

When BCLC conducted its initial enterprise risk management exercise in 2003, generic consequence and likelihood and management effectiveness scales with a 1 to 5 range were provided to BCLC by the consultants. The impact ratings focused on monetary and service provision consequences, while the likelihood ratings considered the chance of occurrence over the next three years.

For this initiative, risk workshops were used for the majority of risk analysis, with risk statements either predetermined or defined in advance using interviews with key internal stakeholders and then voted on by the Executive Committee, the ERMAC team, or a specific project team depending on the context. Voting technology was used at each workshop, with each participant independently rating each risk. After each vote, the software calculated the average score and derived an overall risk rating for each risk. Using voting has a number of benefits, principally allowing a large number of risks to be assessed in a relatively short period of time. Advocates also claim that voting reduces group bias, as results can be presented anonymously and any variations can be discussed.

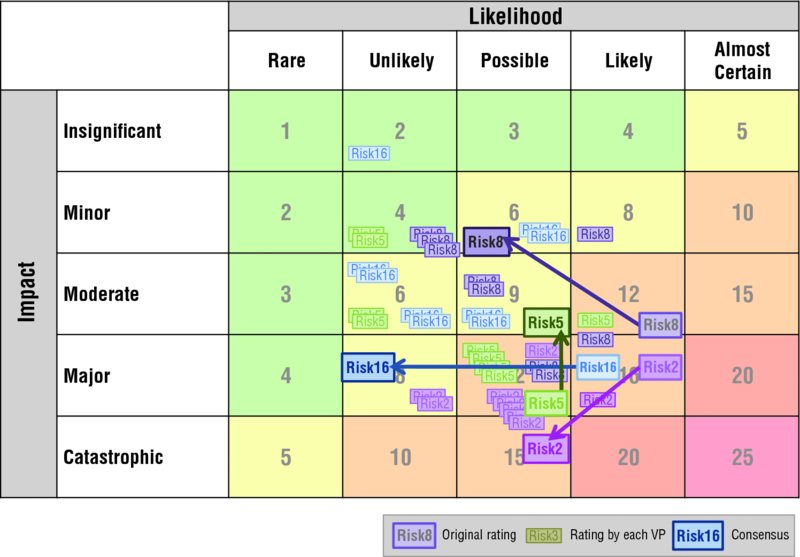

Voters at each facilitated workshop were asked to rate the likelihood that a particular event would occur in the absence of any controls in place to mitigate the risk (known as the inherent likelihood). Each risk was then mapped to one of four categories (see Exhibit 10.8). An additional exercise considered the effectiveness of current control levels for each risk and also the desired level of control in order to identify any risks where it was considered that additional levels of control were required.

Exhibit 10.8 2003 Risk Mapping Approach

The Internal Audit–led exercise in 2006 initially used a very simple scale (high, moderate, low, and very low) when asking participants to identify/report their top three risks, and then introduced a new BCLC-specific impact and likelihood table to assess inherent impact and likelihood, using the same voting and averaging methodology as used in 2003. The new risk criteria considered a range of potential consequences, from threats to product integrity, to media reports, sales, stakeholder relations, regulatory noncompliance, and budgetary impact. The new likelihood ratings included both an assessment of the probability of occurrence and reference to historical incidence and common root causes and control effectiveness. The risks were again grouped into four categories, as can be seen in Exhibit 10.9.

Exhibit 10.9 2006 Internal Audit Risk Matrix

The 2007 enterprise assessment developed the risk assessment framework further, reflecting the additional resources now available to the ERM program with the appointment of a dedicated manager and the engagement of the new ERMAC team. The criteria were revised once more, with metrics developed for each category of consequence, a cleaner likelihood table with measures of both probability and frequency, and a new management effectiveness rating table.

Assessment participants were asked to vote on the impact if the risk event were to occur and the inherent likelihood of that event occurring. As with the previous assessments, the overall rating assigned to each risk was taken as the average, giving a score from 1 to 5 for each risk. A further vote was then conducted on how effective the ERMAC team considered current controls to be for each risk (the “current management effectiveness”). The two scores were then compared and any risks with a high-risk rating and lower management effectiveness rating were identified as requiring management attention.

The two enterprise risk assessments in 2008 in February and November used a very similar approach to the 2007 assessment, except that, instead of reporting on the inherent risk ratings and highlighting any significant gaps between the inherent risk rating and the management effectiveness rating, the management effectiveness metric was used to place each risk in a residual risk matrix, according to the size of the gap. Where the gap showed that controls were insufficient, this was termed a risk (better described as intolerable residual risk), and where the gap showed that controls were excessive, this was classified as an opportunity (to reduce control levels). The final outcome of the exercise is shown in Exhibit 10.10.

Exhibit 10.10 2008 ERM Residual Risk Rating Matrix

This approach was adopted partly in recognition that BCLC had not always put in place sufficient controls for the level of risk, but also because there was a perception that in some areas excessive controls had been implemented, partly in response to the Ombudsman report and subsequent recommendations and partly because some areas of the organization were considered to be risk averse.

From 2009, there was a change in emphasis from primarily inherent to residual risk assessments. This was partly due to the different approach of the new manager, partly due to difficulties with accurately assessing inherent risk, and partly because of a new opportunity with the development of new organizational goals. BCLC had been exploring the concept of balanced scorecards5 as part of developing a more mature approach to performance management, and in early 2009 new risk criteria were introduced based on the new goals. This reinforced the link between risk and wider business and strategic planning, and enabled the development of a smaller set of risk impact categories that resonated with both management and senior leadership. The impact criteria were developed with key managers and validated with the executives, with an annual update incorporated into the risk management planning timetable.

At this time also BCLC ceased to use the voting technology for a variety of reasons, including cost and geographical limitations, and moved to an approach where group workshops prioritized risk but did not undertake formal analysis or evaluation. A variety of visual mapping techniques were introduced with a more hands-on style adopted, requiring workshop participants to engage more directly through the use of techniques such as using Post-its, voting cards, target placement, assigning spots, and drawing process maps. Formal analysis moved to the appropriate subject matter expert with quality assurance provided by the risk manager and then confirmation of risk scoring provided by the relevant member of the executive or project steering group.

In 2011, as an outcome of the Internal Audit ERM review, it was agreed that the criteria were not sufficiently aligned with leadership attitudes to risk, and that too many risks were being reported with a high rating and thus being escalated in the quarterly report. An exercise was conducted with executives to better align the existing risk criteria to organizational tolerance, and to discuss the perception that the organization, or at least some parts of it, was overly risk averse. Perspective was provided through discussion of the balance between risk aversion and excessive risk appetite and the use of the “as low as reasonably practical” principle (sometimes referred to as ALARP or ALARA [as low as reasonably achievable], and described in ISO 31010).

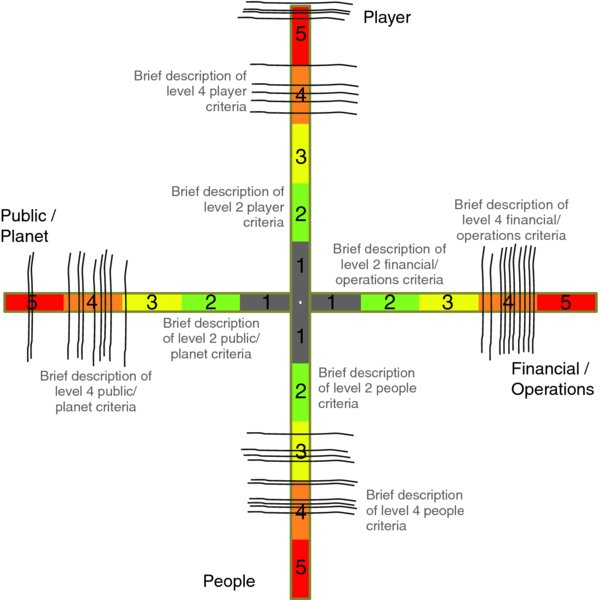

Two activities were undertaken, each designed to look at the four dimensions of impact in the ERM framework to ascertain whether current levels were an accurate representation of the attitude of BCLC leadership toward risk, and to initiate discussion where that attitude varied among the executives.

The first exercise (see Exhibit 10.11) used a poster showing the existing impact criteria, and each executive was asked to mark where he or she believed the current catastrophic or level 5 impact should truly fall on the scale. This clearly shows that the scales in use at the time were generally felt to be misaligned with organizational risk tolerance, in particular for financial/operations and people impacts.

Exhibit 10.11 Impact Scale Evaluation Exercise

The second exercise took a small number of existing and well-understood risks, all currently assessed at a similar risk rating but with impacts across the different dimensions. Each executive was asked to place the risk where he or she believed it lay on the current impact table, again displayed as a large poster. Exhibit 10.12 depicts the mapping for two of the risks, showing both the spread of opinion, and the disparity between the rating at the time and the risk attitude of the executives both as individuals and collectively.

Exhibit 10.12 Specific Risk Impact/Likelihood Evaluation Exercise

The exercises were successful in generating discussion about relative risk tolerances and showed both that the overall evaluation tools were escalating risk at too low a level and also that the risk criteria across the different impact dimensions were not completely aligned to the collective executive risk perception and attitudes.

The impact criteria and the risk evaluation table were adjusted after the executive meeting, and the new approach adopted for the next risk review in March 2011. As a result of changing the criteria, the number of risks escalated to the executive declined from 33 to 10, allowing a much greater focus on the most significant risks, while risks now rated as having a moderate risk level continued to receive focus at the divisional risk review meetings.

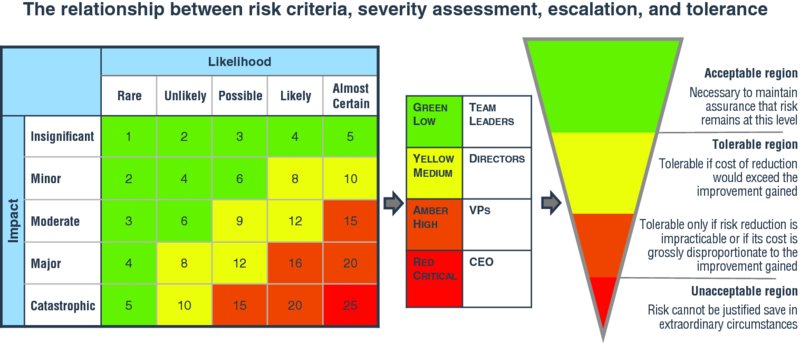

In early 2012, a new risk framework was put in place describing BCLC's now maturing approach to enterprise risk management. The framework contained a section on determining appropriate risk responses, including a formal statement that BCLC had adopted the ALARP approach to determine the appropriate response to risk. This approach divides risks into three regions or zones:

- An acceptable region, where further treatment may be undertaken but is not required

- A tolerable region where treatment should be undertaken dependent on cost/benefit analysis

- An unacceptable region where treatment to lower the risk is mandated

Taking an ALARP approach to risk response allows for flexibility when determining the best approach to managing risk, and reflects that organizations may on occasion choose to adopt higher-risk strategies where the potential reward is deemed to be sufficient, or may elect to carry significant risk where the cost of treatment is felt to be prohibitive.

The relationships between criteria, severity, escalation, and tolerance are set out in Exhibit 10.13.

Exhibit 10.13 Implementing the ALARP Approach to Risk Response

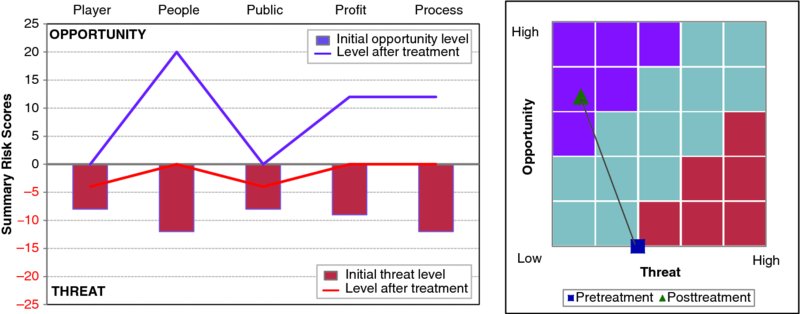

The next significant risk assessment and evaluation development was the expansion of the risk consequence criteria in August 2012 to include positive outcomes. Consideration of positive outcomes from uncertainty was introduced in ISO 31000, but has long been recommended by project management, for example in the Project Management Institute (PMI)'s Practice Standard for Project Risk Management. The concept was introduced for two reasons: to better engage those parts of the organization that were aiming to become highly innovative, and to better assess the risks associated with new initiatives. The new approach enables the comparison of risk with potential reward, and establishes the idea that both threats and opportunities are associated with uncertainty.

The new consequence table was based as previously on the key BCLC goals but for the first time included consideration of both positive and negative impacts, with benefits considered as opportunity and loss/harm as threat. The table has four levels of positive outcomes and four levels of negative outcomes (with a neutral zone bridging the two). BCLC has opted for a symmetrical approach so that a given level of negative outcome in any of the dimensions is balanced by the equivalent level of positive outcome. For example, one of the existing financial criteria references the possibility of making a loss of up to $5 million. Therefore, the parallel positive consequence is a potential gain of up to $5 million. Likewise, in the overall severity matrix, the appetites and tolerances for positive risk follow the same principles already in use for negative risk.

The new table was incorporated into the business case template, with simple graphical maps produced as an outcome of a detailed assessment showing the overall risk profile of any proposed initiative. These maps are used as one of the factors determining both the selection of initiatives and the level of risk management support and monitoring subsequent to approval. The approach has proved very helpful for both risk mitigating proposals to be able to demonstrate value more clearly and for those initiatives that have a more balanced profile to incorporate risk treatment plans from a much earlier stage, allowing for better risk planning and resourcing.

Exhibit 10.14 shows an example of the summary charts produced as an outcome of a business case risk assessment exercise. The business case is for an initiative that is primarily designed to reduce existing risks across a number of organizational objectives. The bars show the current threat and opportunity assessment, while the lines show the anticipated effect of the initiative on the organizational risk profile. The matrix looks at the overall balance between threat and opportunity, with the pre- and post-treatment statuses showing very positive changes. This initiative was approved and is proceeding. Because of the high levels of uncertainty, monitoring of threat mitigation and benefit realization will be important.

Exhibit 10.14 Business Case Risk Assessment Output Example 1

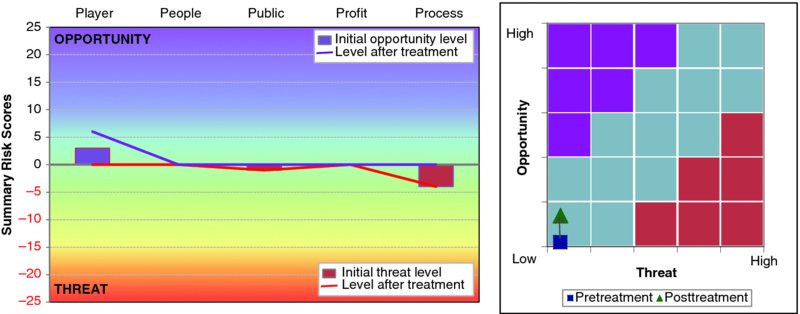

Exhibit 10.15 shows another example, this time for an initiative with very low levels of uncertainty. The overall effect of the initiative on the organization's risk profile is broadly neutral. This initiative was also approved and is proceeding. As levels of uncertainty are low, monitoring will be minimal.

Exhibit 10.15 Business Case Risk Assessment Output Example 2

Although there was a significant learning curve both for the teams participating in the risk assessments and for senior management in interpreting the results, the new approach was endorsed by management and was used again in 2013 with some minor improvements to increase consistency.

Linking discussion of potential rewards with potential problems has supported the development of a more nuanced view of risk across BCLC and proved more culturally acceptable to individuals and groups tasked with developing innovative practices, as there is less of a focus on asking “What could go wrong?” and more emphasis on “What is not certain?” This has helped the ERM program to counter the viewpoint held by some groups that managing risk is a necessary but uninspiring and possibly bureaucratic exercise required by a risk-averse corporation, and has led to a better understanding that becoming risk-aware helps in embracing change and achieving objectives.

CONCLUSION

This case study has described how enterprise risk management has developed over the past 10 years at BCLC, a Canadian crown corporation offering lottery, casino, and online gambling. BCLC's enterprise risk management program has been developed over time through a combination of internal experiential learning and the application of specialist advice. The program's success has been due to the dedication of a number of key individuals, the support of senior leadership, and the participation of BCLC employees.

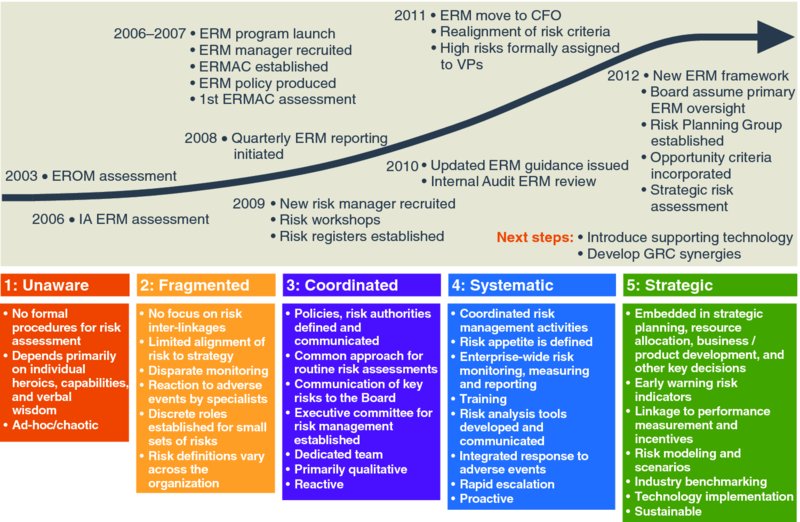

The approach to ERM has evolved from informal conversations supported by an external assessment, through a period of high-level corporate focus supported by a dedicated group of champions using voting technology, to an embedded approach, where risk assessments are incorporated into both operational practice and planning for the future using a variety of approaches, depending on the context. The increasing maturity of the program has been mapped to a simple scale adapted from a model developed by Deloitte (Exhibit 10.16).

Exhibit 10.16 BCLC's Journey toward Risk Management Maturity

BCLC's current approach to managing risk is one that recognizes that, in order to innovate and develop, it needs to embrace change with all the associated uncertainty that brings. At the same time it needs to protect its reputation and preserve the integrity of its systems and processes. Risk awareness and appropriate response are thus essential in both day-to-day and longer-term strategic planning.

BCLC is moving into a more challenging future and working to transform into an increasingly dynamic and innovative organization, where effective risk management will increasingly become a core competency for success. As its leaders reflect on 10 years of enterprise risk management, there are still plenty of challenges ahead in order to continue to sustain and develop its program. In particular they are looking to automate monitoring and reporting.

QUESTIONS

-

Sometimes risk workshops generate so many risks that it is not possible to assess all of them, while on other occasions only a small number of risks are identified and in-depth assessment is possible. What are the advantages and disadvantages of these two scenarios?

-

How do outcomes, causes, and risks differ, and what are the implications of confusing these?

-

Is the term inherent risk helpful? How could it help and/or hinder the assessment of risk?

-

What are the implications of moving from assessments of predefined sets of risks to using top-down objectives based on the balanced score card approach?

-

Contrast the advantages and disadvantages of using voting technology compared with other approaches such as those described in this case study.

NOTES

REFERENCES

- AS/NZS 4360:2004 Risk Management.

- BCLC Annual Service Plan Report 2012/2013.

- BC Ombudsman. 2007. “Winning Fair and Square: A Report on the British Columbia Lottery Corporation's Prize Payout Process.”

- British Columbia Treasury Board. Core Policy and Procedures Manual (CPPM). “Risk Management,” Chapter 14.

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 2004. “Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework.”

- Deloitte & Touche. 2003. “Enterprise-Wide Risk & Opportunity Management (EROM)—Phase 1 Final Report.”

- Deloitte & Touche. 2007. “Report on the Independent Review and Assessment of the Retail Lottery System in British Columbia.” October.

- Ernst & Young. 2010. “Results of the Enterprise Risk Management Benchmarking Study Involving 11 Participating Organizations.”

- ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines.

- Society of Actuaries. 2009, 2010. “A New Approach for Managing Operational Risk.”

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

Jacquetta Goy is the Director of Risk Management Services, Thompson Rivers University and former Senior Manager, Risk Advisory Services at British Columbia Lottery Corporation, responsible for establishing and developing the enterprise-wide risk management program. Prior to that she spent 14 years in the English health service, where she was responsible for setting up and developing the risk, quality, and governance programs for an inner-city health care organization. This involved preparing for a variety of accreditation reviews and inspections, managing quality assurance, audit, complaints, clinical risk, investigations, and root cause analysis. Jacquetta has both participated in and organized a number of conferences on both risk and quality management. She studied international politics at Aberystwyth University, Wales, and has a master's in public health from St. George's University of London. Currently, she is a member of the Canadian Committee for Risk Management and Related Activities, Canadian Standards Association, and one of the Canadian delegates on the international technical committee for risk management (TC262). She can often be found on various LinkedIn risk groups advocating ISO 31000.