The process of risk assessment continues with risk analysis, in which we develop an understanding of the risks. We begin by identifying the likelihood or probability of a threat or hazard having an impact on an information asset, and using that likelihood assessment together with the impact we established earlier, we calculate the overall level of risk.

In risk identification, we examined the general impacts or consequences faced by an information asset, then the threats that might cause them, followed by any vulnerabilities they might possess. These three assessments were carried out in isolation, since at that stage of the risk management process the relationship between them did not matter.

In risk analysis, however, we bring the three assessments together, along with any controls already implemented, and examine the impacts that might occur to information assets as a result of specific threat events. This may also require an understanding of any motivations that might exist for deliberate incidents.

Firstly, we assess how likely it is for any given threat or hazard to exploit a vulnerability and cause harm to an information asset.

ASSESSMENT OF LIKELIHOOD

As we mentioned earlier, the likelihood of a threat taking advantage of a vulnerability to cause harm to an information asset will depend on a number of factors, including:

- The value of the asset to the attacker, which is usually, but not always, financial.

- The history of previously successful attacks.

- The risk of an attacker being detected either during or following an attack, whether successful or not.

- The complexity of the attack.

- The motivation of the attacker, which is sometimes financial or sometimes the result of a grievance.

- The skills and tools required to carry out the attack.

- The level of any vulnerabilities within the information asset, including how well they are known.

- The presence or otherwise of existing controls.

Clearly, for environmental hazards, errors and failures, the concept of an attacker has no meaning, but for the other forms of threat described – physical threats, malicious intrusion or hacking, misuse, abuse and malware – an attacker will be present in some form, and this will have a profound effect on the likelihood of the attack succeeding.

An attacker may simply wish to steal the information asset or make a copy of it; this is straightforward theft, and hence has a confidentiality impact. Alternatively, the attacker may wish to alter the information asset to gain some benefit – a higher examination grade, for example – or to reduce the benefit to the information owner, perhaps because of some perceived grievance – to cause customer dissatisfaction, for example. These have an integrity impact on the information asset. Finally, the attacker may wish to deny the information owner and/or the owner’s customers rightful access to the information asset, again possibly because of some perceived grievance, and this is an availability impact.

Clearly, the greater the motivation an attacker has, the greater will be the likelihood of the attack being successful, and possibly also the greater the impact on the information asset.

However, likelihood or probability can still be extremely difficult things to rate. Many of the events we will consider occur quite randomly, rather than at predefined or likely intervals, and so we are unable to determine exactly when a particular incident is likely to happen. Estimation is therefore the order of the day, but we need to take care with our approach so that it is both meaningful and consistent.

As with the assessment of impact, we turn to the two possible methods of likelihood assessment – qualitative and quantitative.

Qualitative and quantitative assessments – which should we use?

Qualitative assessments are almost always subjective. The terms ‘low’, ‘medium’ and ‘high’ give a general indication of either the degree of impact or the likelihood of an event occurring, but little more. Quantitative assessments, on the other hand, can be very specific, and are generally rather more accurate. The main problem with quantitative assessments is that the greater the level of accuracy that is required, the greater will be the amount of time the assessment will take to complete. Only in a very few cases is total accuracy a requirement.

It may be worthwhile taking an initial qualitative pass in order to gain an idea of the levels of risk and to identify those risks that are likely to be severe, with the objective of a more quantitative assessment later on.

Alternatively, a compromise solution often works well, since it can combine objective detail with subjective description. Instead of spending significant amounts of time in establishing the exact likelihood of a particular event, the compromise solution takes a range of likelihood values and assigns descriptive terms to them. This is also known as semi-quantitative assessment. So, for example, we might decide that in a particular scenario, the term ‘very unlikely’ approximates to an event that occurs once in a decade; ‘unlikely’ to one that occurs once a year; ‘possible’ to one that occurs once a month; ‘likely’ to one that occurs once a week; and ‘very likely’ to one that might occur at any time.

The criteria upon which these decisions are made may have some inherent business origin, and may well be based on input from an panel of ‘experts’, who will reach some form of consensus on the most appropriate values. This approach is sometimes referred to as the Delphi method, and, even if the decisions are incorrect in any way, the organisation can be confident that they have been reached by a formal method.

Although this provides boundaries for the levels, there will be a degree of uncertainty about the upper and lower limits of each, but, with forethought, the ranges should be sufficient to provide a fairly reasonable assessment while placing it in terms that the board will understand quickly. Clearly, these ranges will differ from one scenario to another, but will set a common frame of reference when there are a substantial number of assessments to be carried out. These ranges should be agreed when setting the criteria for assessment.

Fully quantitative assessment relies on our being able to predict the probability of an event occurring based on the likely frequency of it doing so. This requires a knowledge or experience of statistics, which is outside the scope of this book, but unless probability information is available and deemed to be trustworthy, frequency is unlikely to yield reliable results.

Historical data may be useful in providing an initial assessment and in developing appropriate likelihood scales, but it is important to base these on sufficient data so that the results are meaningful, since too little data will almost certainly provide a skewed view of likelihood.

Another problem that increases the uncertainty of likelihood assessments is that of proximity. Just because an event occurs statistically once every 10 years does not mean that it will not occur in two successive years or, conversely, that it will occur at all in the next 20 years.

Likelihood may also be influenced by other factors; for example, when a new vulnerability is discovered, or when some newsworthy event provides attackers with a new-found opportunity, such as the development of a new form of treatment for a disease, allowing them to send out spam emails inviting potential customers to purchase medicines at a low cost.

If quantitative assessment proves to be too challenging, we may opt instead for simple qualitative assessment. However, as with impact assessment, qualitative likelihood assessment tends to be very subjective, and the terms ‘highly unlikely’ and ‘almost certain’ mean little except to the person who sets them.

In order to provide a more objective likelihood assessment, we might combine a qualitative scale with quantitative values, as we suggested with impact assessment, so that we can place each assessment on a meaningful basis. For example, severe cold weather-related events tend to be more common in the winter months, while others, such as extreme flooding, may only occur only once in every few years and at any time of year. The Environment Agency in the UK provides estimates of the possible depth of floodwater, but, as always, these are only estimates and neither the extent of flooding nor the frequency at which it might occur can be relied upon for accurate likelihood determination. The timeframe scale for this kind of event might therefore range from months to decades.

Alternatively, hacking attempts can and do occur much more frequently, and so a timeframe scale for these would be rather different.

The likelihood of whichever kind of threat or hazard we face must therefore be judged against an appropriate scale devised as part of the setting of general risk management criteria, and if the worst-case scenario is used for likelihood assessments, this should ideally be the standard for all.

An example of possible likelihood scales for the different categories of threats described earlier is shown in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Typical likelihood scales

The final stage in the assessment of likelihood is to place it against each threat identified earlier in the risk identification process, so that we can begin the next stage – risk analysis.

RISK ANALYSIS

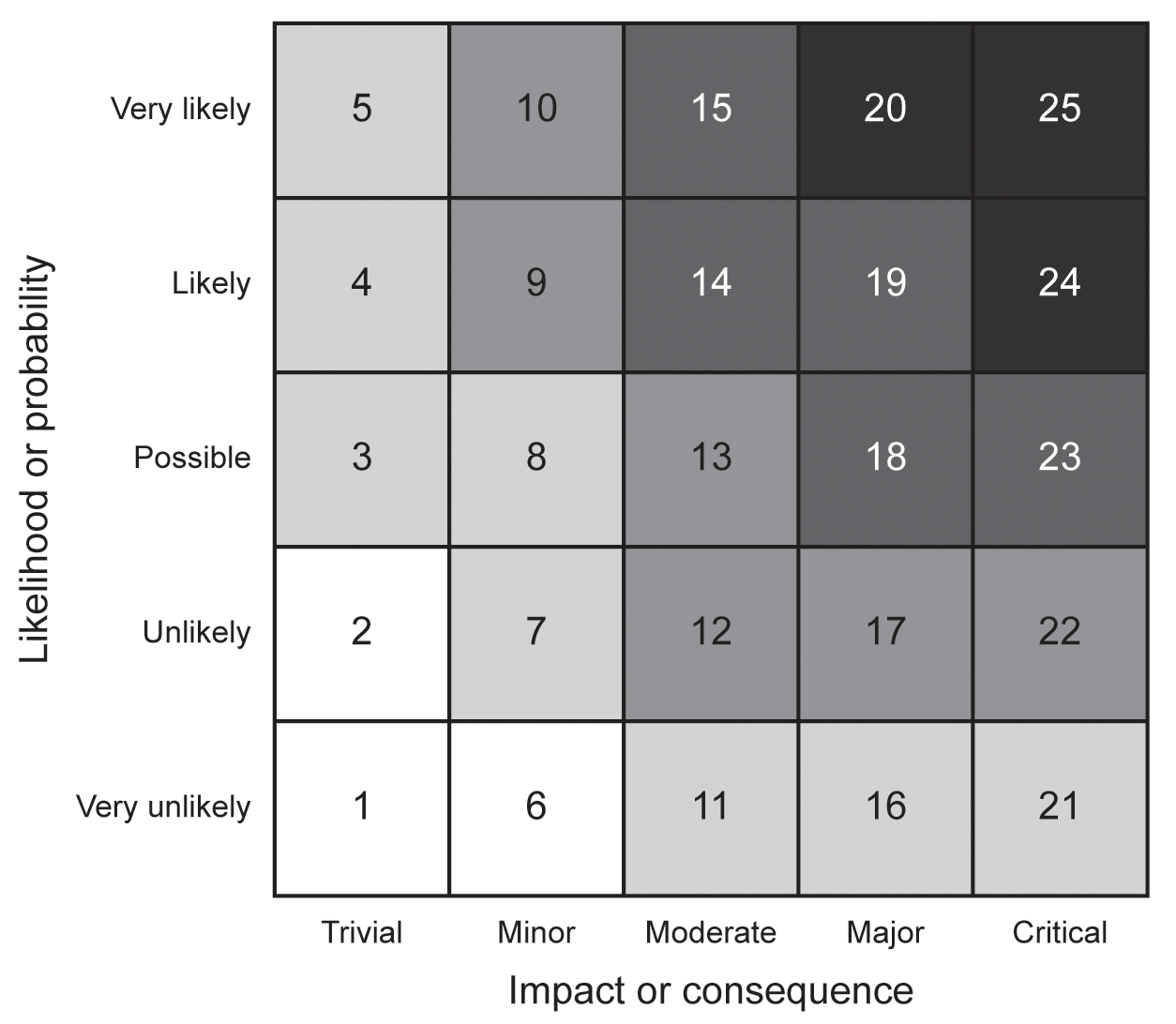

Once we have assessed the impact or consequence of an incident and the likelihood of it occurring, we are in a position to analyse the risk. Typically, this is carried out using a risk matrix of the type shown in Figure 6.1.

A risk matrix is simply a tool to assist in the ranking of risks in terms of overall severity, and in order to help prioritise the assessed risks for treatment. Since it is purely a visual representation of the risks identified, it should only be used at the very end of the risk assessment process, once both the impact and the likelihood have been assessed.

Since we will have been consistent in using scales that truly represent the impact and the likelihood regardless of the type of threat, we can safely plot every impact and likelihood assessment on the matrix. In this example, a simple scale of 1 to 25 is defined.

If there are a number of risks assessed, it may be helpful to number them in some way so as to avoid too much clutter on the risk matrix itself.

This allows us to prioritise the risks into five different rankings:

- Those risks in squares 1, 2 and 6 are very low risk, and we can probably accept them.

- Those risks in squares 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 16 and 21 are not urgent, but may require treatment.

- Those risks in squares 9, 10, 12, 13, 17 and 22 are worth treatment.

- Those risks in squares 14, 15, 18, 19 and 23 are important and require treatment.

- Those risks in squares 20, 24 and 25 require urgent treatment.

However, this presents a rather simplistic view of risks when it comes to later prioritisation, since, if we are dealing with a very large number of risks, a significant number could be ranked as urgent and we would have no easy way of prioritising them for treatment. For that reason we might instead use an enhanced risk matrix, in which a slightly altered scale of 1 to 25 is defined, and some bias is given to those risks that are more likely to occur, as shown in Figure 6.2.

We will now be in a position to record the risk ranking value and begin prioritising the risks for treatment. The next stage in this process is to transfer everything we know about the risks to a risk register.

RISK EVALUATION

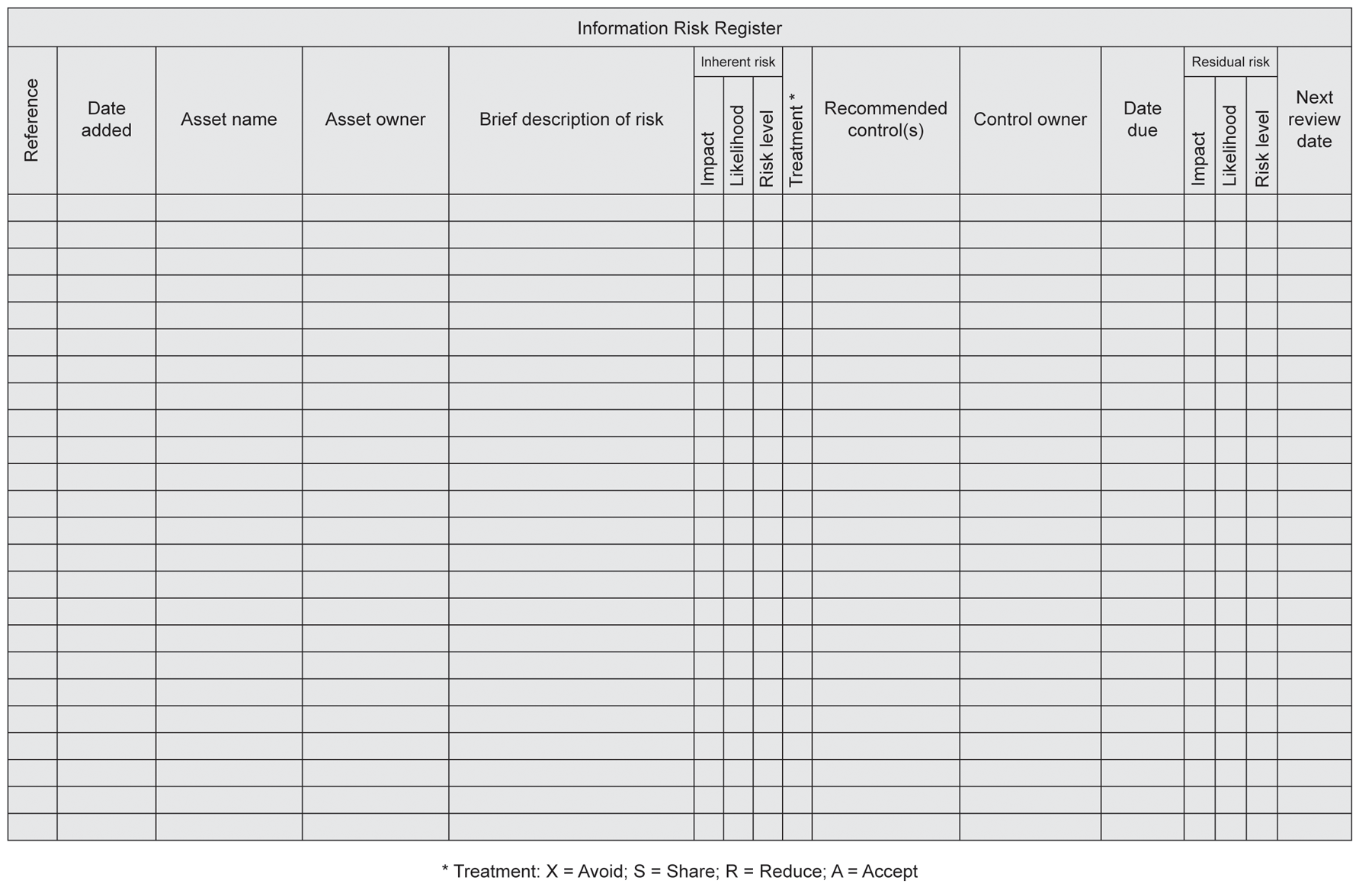

Risk evaluation is the stage in which the various risks analysed are transferred onto a risk register and agreement is reached on which risks require treatment and examines how this should be achieved.

The risk register

The risk register is a method of tracking all risks identified within the information risk management programme, regardless of whether or not they are able to be treated by avoidance or termination, transfer or sharing, modification or reduction, or to be accepted or tolerated.

There is no set structure for a risk register, but it should be remembered that ‘less is more’, and that too much information can render the risk register unusable. It is better, therefore, to record only the very necessary information in the risk register and to provide links – possibly hyperlinks – to any background information. The following information is necessary and sufficient for completeness:

- A risk reference number, possibly prefixed by the organisation’s department name.

- The date the entry was added to the risk register.

- The name of the information asset.

- The name of the asset owner1.

- A brief description of the risk the asset faces.

- The level of impact assessed.

- The likelihood assessed.

- The resulting risk level.

- The recommended operational control(s).

- The name of the person responsible for implementing the control(s).

- The date by which the controls should be in place.

- The next review date for the risk.

It may also be desirable to indicate whether the control(s) have been successful.

Some organisations develop a Structured Query Language (SQL) database to act as a risk register, since this can be made prescriptive in terms of who may make changes, and how and when the entries are made or changed; smaller organisations often find that a simple spreadsheet is sufficient for their needs, as shown in Figure 6.3.

There is, however, a major caveat when it comes to sharing the risk register. The register itself becomes a valuable information asset, and may contain information that could be detrimental to the organisation if it were to become publicly available, since it provides a comprehensive list of all the organisation’s information assets and the risks they face. Therefore, the risk register should be protected with its own set of controls and only shared with those people within the organisation who have a genuine need to see it.

It will be clear at this point that some fields within the register cannot yet be completed, since we have not actually conducted the risk evaluation. This is the next and final stage in the risk assessment process.

Risk evaluation

In the process of risk evaluation, we take each risk in turn and compare it with the risk criteria, which we covered in Chapter 3 – The Information Risk Management Programme.

We begin by comparing the potential impact or consequence with the organisation’s risk appetite for that particular information asset. If the impact is less than the level set as the risk appetite, the organisation may decide to accept the risk, but to record the fact and ensure that the risk is monitored over time in case either its impact or likelihood changes.

Next, we compare the risks with the risk treatment criteria – also established in Chapter 3 – to decide on the most appropriate form of risk treatment, which includes risk avoidance or termination, risk transfer or sharing, risk reduction or modification and risk acceptance or tolerance.

The recommendation at this stage of the process will only be which of the strategic options the organisation should employ, and will not go down to the tactical or operational level, since this is part of the risk treatment process.

Some organisations assist the recommendation process by introducing three separate bands of risk:

- An upper band in which the level of risk is regarded as being intolerable, regardless of the costs or complexities of treatment.

- A middle band in which the cost/benefit of treatment is considered along with other risk appetite criteria.

- A lower band, in which the level risk is so low that it can clearly be accepted or tolerated without the need for debate.

We should also remember that, although any of these choices might reduce the risk to a level below that of the organisation’s risk appetite, it may well be possible to reduce it further by employing more than one of the risk treatment options and, in addition to recommending which methods to employ, the organisation may also need to consider in which order they should be employed.

Again, at this point in the process it may become clear that either the risk appetite criteria or the risk treatment criteria are insufficiently well defined to allow the organisation to make an informed decision as to the most appropriate form of risk treatment, since at the time too little may have been known about the exact nature of the risks. These criteria may therefore require refinement, and the evaluation process must be repeated.

Likewise, there may be risks for which the recommended option still remains unclear, and in such cases the recommendation might be to conduct a further and more detailed risk assessment in order to better understand the risk and to make a more informed choice as to the method of treatment.

The recommendations should also provide some indication of the likely cost of treatment, since if the cost outweighs the benefit, the organisation may decide to accept the risk as being too expensive to treat. As with any other accepted risk, this should be documented and monitored over time.

While recommendations on risk treatment tend to be based upon the acceptable level of risk for each information asset, it is important that the evaluation process takes into account three key attributes:

- The aggregation of a number of lower-level risks may result in significantly higher overall risk.

- The importance to the organisation of any information asset when compared to others.

- The need to consider whether legal, regulatory and contractual risks might be more damaging to the organisation than others.

The output of the risk evaluation process will be:

- Whether or not a risk requires treatment and, if so, which strategic option(s) are recommended.

- A prioritised list of the risks identified for treatment.

- An updated risk register reflecting the recommendations made.

It is normal practice at this point to submit a proposal for the overall risk treatment plan to senior management for consideration, together with any business cases required for treating those risks for which the cost exceeds a set threshold, again defined as part of the criteria for the information risk management programme.

The component parts of a business case are described in greater detail in Chapter 7 – Risk Treatment.

SUMMARY

In this chapter, we have examined how we can assess the likelihood of a threat occurring, how we assess the resultant risk, and how we evaluate this risk in order to treat it. The next chapter describes the process of risk treatment.

1 While one person or department may be the asset owner from the point of view of impact, it is quite conceivable that another person or department might be the owner from the point of view of likelihood. Therefore, the risk register will need to record this.