Now we have completed the risk assessment process, it is time to begin to consider how to deal with the risks we have identified. The actions we take to treat risk are referred to as controls.

A control is any measure or action that modifies risk. Controls include any policy, procedure, practice, process, technology, technique, method or device that modifies or manages risk. Risk treatments either become controls or modify existing controls once they have been implemented.

However, some controls may monitor risks without actually modifying them in order to ensure predictability of the process. Actual risk modification then only occurs if the monitoring activity detects results that deviate from those expected.

Controls are the tools we use to take a level of inherent risk and modify it to a level that falls within the organisation’s risk appetite, at which point the organisation is willing to accept the residual (if any) risk.

This chapter begins by taking an overview of the principal options for risk treatment.

Firstly, at the strategic risk treatment level, we have four options:

- To avoid or terminate the risk.

- To transfer or share the risk.

- To reduce or modify the risk.

- To accept or tolerate the risk.

At the end of this process, there may remain some ‘residual’ risk that we cannot treat, simply because we have exhausted all other possibilities or because the cost of further treatment would be more costly than the financial losses if the risk came to fruition. In this case, we must accept this residual risk, but subject it to ongoing monitoring.

In earlier chapters, we discussed the criteria for information risk management, and noted that there is a level of risk for each type of information asset, known as the risk appetite, above which the organisation will wish to treat the risk, and so it is important to understand that there will be situations in which more than one choice of treatment may be required in order to take the level of risk to a point that is acceptable to the organisation, bringing it below the risk appetite level.

Next, for each strategic risk treatment option, there are one or more tactical options:

- detective controls;

- corrective controls;

- preventative controls;

- directive controls.

Finally, at the operational level, we have three types of control:

- physical controls;

- procedural controls;

- technical controls.

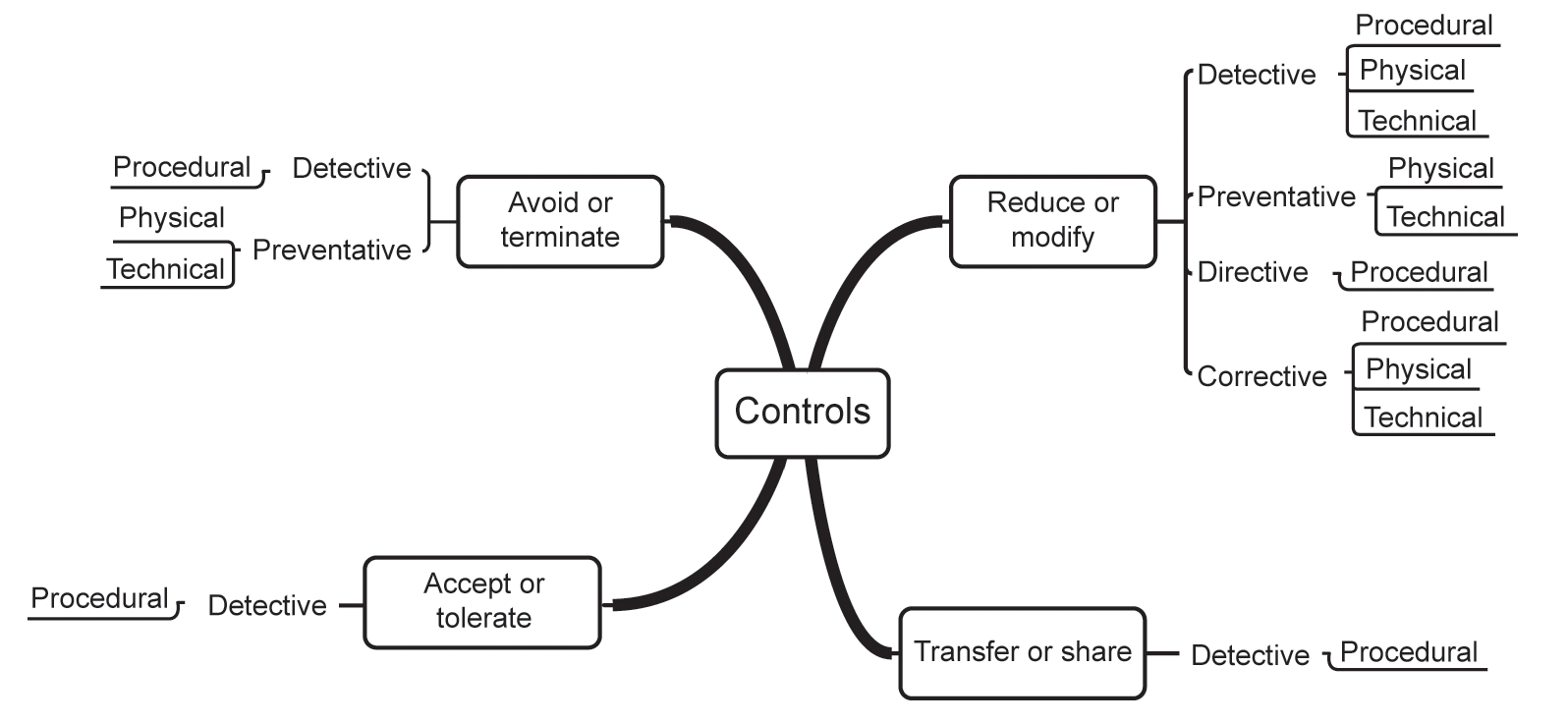

Figure 7.1 illustrates all the possible combinations of risk treatment, and we shall deal with each of these in turn, but for the moment let us look at the start of the process for deciding which strategic option or options are most suitable.

Figure 7.1 The overall scheme of risk treatment options

STRATEGIC RISK OPTIONS

Strategic risk management controls themselves do not actually treat the risk, but set the approach for treatment, rather like giving travel directions – ‘Head north/south/east or west’. Figure 7.2 illustrates the process for determining the most appropriate strategic risk option.

Risk avoidance or termination

Firstly, we will examine whether or not we can avoid or terminate the risk. This implies either not commencing an activity that would incur risk or to cease doing it if it has already commenced.

For example, if the organisation were considering building a new factory and we had identified that there was a significant risk due to the building site being within a known flood plain, we would recommend that the organisation found a more suitable location. As long as the organisation accepted this recommendation, that particular risk would be terminated immediately.

However, it should be remembered that ceasing or terminating some risks may introduce others. In the example above, if the building the factory in the original location was halted, there would be a requirement either to find a more appropriate location, or live with the results of not building at all. Either of these options would potentially introduce additional risks.

As a slightly different example, if the organisation were in the process of moving large amounts of information to a cloud service provider and we had identified that this would place the organisation’s confidential customer information in a jurisdiction that does not meet the requirements of the data protection legislation, we would recommend that the project be halted.

This would terminate that particular risk, but there would be two secondary effects resulting from a decision to stop the project. Firstly, there would be some cost for any work that had already been carried out, and possibly some contractual penalties; and secondly, the organisation would be left with the problem of finding a replacement cloud service supplier if it still wished to outsource the information, and again there would be a cost involved in doing this.

Risk transfer or sharing

If terminating the risk is not an option, the next option is to decide whether the risk can be transferred or shared with a third party.

This might seem to be a simple way of disposing of a risk, but it is not as straightforward as it may first appear. While an organisation may transfer or share the actual treatment of the risk to a third party, the responsibility and accountability for the risk remains with the organisation itself, and in some situations it may not be possible to transfer or share the entire amount of the risk.

An example of the first of these possibilities is where an organisation places its confidential customer information with a cloud service provider whose systems are attacked by hackers and the information is made public. Although the outsourcing organisation would almost certainly have a legitimate claim of negligence against the cloud service provider, the responsibility for the information leakage would still lie with the organisation, and the Information Commissioner would expect to penalise the organisation itself rather than the cloud service provider.

So, although the risk has been shared, there remain a number of issues that the organisation faces, including secondary and indirect risks. All these must be taken into account when transferring risk.

An example of the second instance might be where an organisation takes out an insurance policy against the revenue losses incurred if their information systems fail. An insurance company might be happy to take on the entire risk, but the premiums to cover all possible losses might exceed the organisation’s budget. In order to reduce the premiums to an acceptable level, apart from demanding a number of guarantees such as fully tested DR systems, the insurer might well set an upper limit on the possible payout in the event of a claim, so the organisation would be faced with accepting some residual risk.

Risk reduction or modification

In the past, this was often referred to as risk treatment, but the definition has now become more precise so as to avoid confusion with other forms of treatment.

When an organisation examines the possibilities for reducing or modifying risk, it means reducing the impact, reducing the likelihood or sometimes a combination of both, since there are a number of different approaches to this at tactical and operational levels that may be used in combination to bring the level of risk down to below the organisation’s level of risk appetite.

One typical example of risk reduction is to reduce the likelihood of unauthorised remote access by replacing user ID and password authentication with two-factor authentication using a smartcard, security token or biometric scanner as well as the existing user ID and password. This would strengthen the authentication process considerably and reduce the likelihood of a successful intrusion, but the organisation would then have to balance this benefit against the costs of deployment and ongoing support, together with the additional risk that a lost or stolen token could present a new threat!

Another example is to reduce the impact of theft of a company laptop by encrypting the entire hard drive. The capital value of the laptop would still have been lost – although the impact of this might have been reduced under an insurance policy – but the information contained on the laptop would be secured and almost impossible for the thief to recover.

Again, organisations might have to accept some residual risk – the replacement cost of the laptop in this last example would be covered, but there would be some additional expenditure in configuring it and installing replacement software.

Risk acceptance or tolerance

The final strategic option is to accept or tolerate the risk. Ordinarily this only happens when a risk is too costly to treat by any other means or, following other forms of risk treatment, has reached a point where no further treatment is possible.

The most important aspect of risk acceptance is that it differs entirely from ignoring risk, which should never be an option under any circumstances. Accepted risks must always be documented as such and reviewed either at intervals, in case the level of risk has changed in the meantime, or if there has been a sudden change in either the impact or the likelihood that produced the risk in the first place.

Not all forms of strategic control involve the use of all forms of tactical control, as we shall see in the next section.

TACTICAL RISK MANAGEMENT CONTROLS

Using the earlier analogy, tactical risk management controls are similar to suggesting the route – ‘Take the motorway as far as junction 20’. They consist of four different types: detective, preventative, directive and corrective.

As with strategic controls, tactical controls themselves do not actually treat the risks, but determine a more specific course of action.

Detective controls

Detective controls are those controls that advise or warn the organisation that an incident is taking place, but that is all they do – they themselves do not change either the impact or the likelihood of any risk, but operate alongside other types of tactical controls.

If action needs to be taken as a result of the warning, then this must necessarily be as a separate control (probably corrective) initiated either automatically by the detecting system or by a member of staff who is alerted by the warning.

An example of a detective control is an alarm generated when an intruder forces open a security gate or door.

Preventative controls

Preventative controls are designed to stop an incident from taking place before it has begun. The choice of any subsequent operational control will determine the actual steps to be taken, but preventative controls will ultimately reduce or eliminate the likelihood of an incident occurring, and may therefore reduce or terminate the risk.

An example of a preventative control is the lock on a door or window to an area to which an intruder might otherwise have free access.

Directive controls

Directive controls are totally instruction-based. They comprise policies, procedures, processes and works instructions, all of which dictate what must or must not be done.

As with detective controls, directive controls do not change either the impact or the likelihood of an incident occurring, since they only dictate what may or may not be done. If people follow the organisation’s policies, then the controls will be successful, but if they do not, the controls will not be effective. For this reason, many organisations like to couple directive controls with other types, such as preventative or corrective, in order to enforce the policies.

An example of a directive control is a policy stating that passwords must consist of a minimum number of alphanumeric characters, sometimes requiring both upper and lower case and so-called ‘special’ characters such as hyphens. This could be reinforced by a preventative control within the computer’s operating system that forced users to update their passwords according to the constraints of the policy.

Corrective controls

Corrective controls are those that, through appropriate operational controls, will make a difference either to the impact or to the likelihood of a risk. Corrective controls are invariably introduced after an event of some kind has occurred or has been detected, and their purpose is to fix the problem. An example of a corrective control is the requirement to update a firewall rule in response to a newly discovered threat.

Not all forms of tactical control involve all forms of operational control, as we shall see in the next section.

OPERATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT CONTROLS

Using the earlier analogy, operational risk management controls are similar to providing more detailed directions to the destination, such as ‘Now take the A4303 east, then the A426 south for 2½ miles’.

Operational controls come in just three varieties: procedural, physical and technical, also known sometimes as people, environmental and logical controls, respectively. As with tactical controls, operational controls may be used singly, or in conjunction with others in order to minimise a risk.

Procedural controls, as the name suggests, simply put procedures in place to set out actions that users and technical staff must or must not take in any given situation. Procedural controls on their own do not change either the impact or the likelihood of a risk, but do so only where users follow them.

An example of a procedural control is that of a clear desk policy stating that users must leave no materials (for example books, papers or electronic media) on their desk when out of the office. This is in fact a directive/procedural control, and is frequently used in conjunction with the requirement to lock a computer screen when the user is away from their desk.

Physical controls

Physical controls are those that address physical and environmental threats, and as such always change either the impact or the likelihood of the risk. Physical controls may contain a technology element, but this is invariably unrelated to the information itself, merely pertaining to a technical solution to a physical risk.

An example of a physical control (actually detective/physical) is a CCTV system to monitor the perimeter of a building.

Technical controls

Technical or logical controls refer generally to those controls that are directly related to the technology that underpins (or is) the information-supporting infrastructure. Technical controls may be implemented either in hardware or in software, and frequently both.

An example of a corrective/technical control is that of configuring a virtual local area network (VLAN) environment in order to segregate live and test networks.

EXAMPLES OF CRITICAL CONTROLS AND CONTROL CATEGORIES

The following sections list the chief controls suggested by:

- the Centre for Internet Security Controls Version 8;

- ISO/IEC 27001:2017;

- National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-53 Revision 5.

The Centre for Internet Security Controls Version 8

A number of organisations have published a list of the 18 most critical security controls, based upon the Centre for Internet Security Controls Version 8.1

While this is not a comprehensive list of controls, it does provide a good starting point for organisations that have conducted their risk assessments but are unsure where to begin with risk treatment. These controls are described more fully in Appendix D.

No. | Control title |

Basic controls | |

1 | Inventory and Control of Enterprise Assets |

2 | Inventory and Control of Software Assets |

3 | Data Protection |

4 | Secure Configuration of Enterprise Assets and Software |

5 | Account Management |

6 | Access Control Management |

7 | Continuous Vulnerability Management |

8 | Audit Log Management |

9 | Email and Web Browser Protections |

10 | Malware Defences |

11 | Data Recovery |

12 | Network Infrastructure Management |

13 | Network Monitoring and Defence |

14 | Security Awareness and Skills Training |

15 | Service Provider Management |

16 | Application Software Security |

17 | Incident Response Management |

18 | Penetration Testing |

ISO/IEC 27001:2017 controls

Reference | Title (number of controls) |

A.5 | Information security policies (2) |

A.6 | Organisation of information security (7) |

A.7 | Human resource security (6) |

A.8 | Asset management (10) |

A.9 | Access control (14) |

A.10 | Cryptography (2) |

A.11 | Physical and environmental security (15) |

A.12 | Operations security (14) |

Communications security (7) | |

A.14 | System acquisition, development and maintenance (13) |

A.15 | Supplier relationships (5) |

A.16 | Information security incident management (7) |

A.17 | Information security aspects of business continuity management (4) |

A.18 | Compliance (8) |

Although the primary ISO standard for information risk management is ISO/IEC 27005:2018, it contains no detailed information on suitable tactical or operational controls for risk treatment, restricting itself instead to the strategic level only. Instead, ISO/IEC 27001:2017 provides a comprehensive list of 114 separate operational level controls, grouped into 14 categories in its Appendix A. A more detailed description of the controls can be found in ISO/IEC 27002:2017 in its sections 5–18.

These control categories are expanded and described more fully in Appendix D.

NIST Special Publication 800-53 Revision 5

Identifier | Family (number of controls) |

AC | Access Control (24) |

AT | Awareness and Training (5) |

AU | Audit and Accountability (16) |

CA | Security Assessment and Authorisation (8) |

CM | Configuration Management (11) |

CP | Contingency Planning (12) |

IA | Identification and Authentication (12) |

IP | Individual Participation (6) |

IR | Incident Response (10) |

MA | Maintenance (6) |

MP | Media Protection (8) |

PA | Privacy Authorization (4) |

PE | Physical and Environmental Protection (22) |

PL | Planning (9) |

PM | Program Management (32) |

PS | Personnel Security (8) |

RA | Risk Assessment (9) |

SA | System and Services Acquisition (20) |

SC | System and Communications Protection (42) |

SI | System and Information Integrity (19) |

Although the primary NIST publication on information risk management is Special Publication 800-30, it contains no detailed information on risk treatment or the selection of controls. NIST Special Publication 800-53 Revision 52 lists 283 separate operational level controls, grouped into 20 categories, and maps them against ISO/IEC 27001:2017 controls in its Appendix I.

These control categories are expanded and described more fully in Appendix D.

SUMMARY

In this chapter, we have examined strategic, tactical and operational controls, and have looked in greater detail at some of the more critical controls and control categories as identified in a number of international standards.

Before we can begin applying these controls, we will probably be required to present the results of the information risk management programme to date in order to secure funds and people resources to undertake the risk treatment activities we have selected. This part of the programme begins with developing and presenting one or more business cases.

1 See https://www.cisecurity.org/controls/.

2 Joint Task Force (2020) Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations. (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD), NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-53, Rev. 5. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-53r5.