Insightful Ways of Thinking for Managers

…if one out of five opportunities is interesting enough to work on, maybe one in five of those ends up being worth doing. That might be a function of risk. That might be a function of price. There are all the variables. But you have to be constantly sorting and choosing and prioritizing.

—Sam Zell

The challenge in being a good leader is in knowing when to double down on innovation investments.

—Stephanie A. Burns

Chairman & CEO

Dow Corning

In this chapter we discuss insightful ways of thinking about management processes. Quality must be an integral part of the strategic plan but must be thought of more broadly than is typical in order to be of real, long-term strategic value to the organization. Organizations must have the insight to overcome fear of setting audacious goals for the organization. Hand in hand with setting audacious goals is the necessity for a high tolerance for risk and a new way of thinking about failure. Insightful organizations react differently to failure. They encourage the right kind of mistakes and see mistakes as opportunities to learn. We end the chapter with a discussion of the difference in thinking and skills required to successfully transition from insightful technical professional to insightful professional manager.

Strategic Quality Management and Audacious Goals

The Strategic Quality Management Process: Overview1

Virtually every organization does some form of strategic planning. A smaller number of organizations effectively deploy those plans. Fewer still engage in meaningful evaluation of the effectiveness of the deployed plans. Too often, the strategic plan is addressed once a year and then put onto a shelf until the next strategic planning retreat.

Most strategic plans pay at least lip service to quality. Often mission and vision statements contain mention of “being known for the quality of our products” or something similar. Often quality is viewed as a tactical means of achieving some of the strategic objectives. However, in insightful organizations, quality is an integral component of the strategic management process.

Strategic quality management has been variously defined as a “systematic approach for setting and meeting quality goals throughout the company…with upper management participation in managing for quality to an unprecedented degree,”2 and as “the driving force to the survivability and competitiveness of a firm.”3

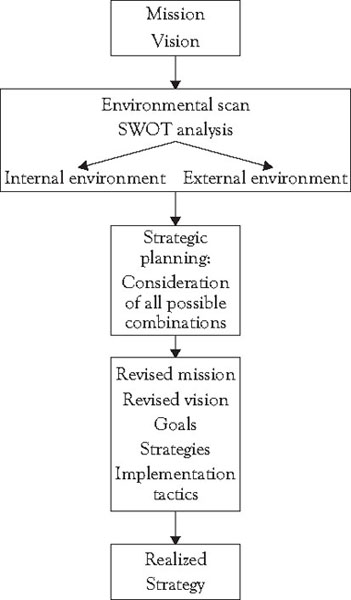

Strategic management involves three elements: strategic planning, strategic deployment, and strategic evaluation and control. Strategic planning starts with establishing a mission and vision for the organization. While the responsibility of top management, this process should involve all constituents of the organization.

Strategic Planning

Mission and vision. The strategic planning process (see Figure 5.1) begins with establishing the organization’s mission and vision. The mission defines the organization’s purpose and the business it is in. The vision defines where the organization plans to go. The process of defining mission and vision, when taken seriously, creates a dynamic wherein the organization addresses fundamental questions about the business it is in, where it is relative to competitors, and how it plans to change in the future. It is important to develop sufficiently broad mission and vision statements to ensure they provide a basis for the organization to act quickly to take advantage of technological advances and other significant changes in the environment. Mission and vision are dynamic, so continuous input should be obtained from constituents and the rest of the general environment and modifications made as needed.

Figure 5.1. The strategic planning process.5

It may be helpful in defining the organization’s mission and vision to ask the five framing questions proposed by Keller and Price4 which were discussed in chapter 3:

- Aspire: Where Do We Want to Go?

- Assess: How Ready Are We to Go There?

- Architect: What Do We Need to Do to Get There?

- Act: How Do We Manage the Journey?

- Advance: How Do We Keep Moving Forward?

Environmental scan. After defining its mission and vision, the organization then scans its internal environment to identify strengths and weaknesses and its external environment to identify opportunities and threats. This is often referred to as SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis. It is important that the scan of the external environment includes the general environment not just the task environment of the organization. Organizational leaders must move up a level in their thinking about the environment because opportunities and threats can come from anywhere. Audio cassettes were not made obsolete by better magnetic recording technologies but by digital recording technologies which used bumps on a plastic disk instead of magnetic particles to reproduce music. This threat was invisible if the external environment was defined to include only competitors in the magnetic media industry. Moving up a level in thinking about the environment will be discussed later in this chapter.

Strategic planning. The results of the environmental scans then are analyzed and provide valuable input to the strategic planning process. During this step planners consider all possible combinations of internal and external factors that were identified by the SWOT analysis. Plans to address threats and exploit opportunities in the external environment are melded with plans to shore up weaknesses and exploit strengths identified in the internal environment. This process often requires revisions to the mission and vision. The result of the strategic planning process is a strategic plan with goals, strategies for achieving those goals, and implementation tactics.

Don’t listen to those who say you’re taking too big a chance. [If he had], Michelango would have painted the Sistine floor.

—Neil Simon6

The insightful organization assures that some of its goals are audacious ones—often referred to as stretch goals or BEHAGS, Big Hairy Audacious Goals. These audacious goals are designed for longer term, more radical change than the typical strategic goals. Through the 1990s Bronson Methodist Hospital in Kalamazoo, Michigan set goals designed to make it the system of choice in the region. In 1999, under the visionary leadership of CEO Frank Sardone and Senior V.P. Susan Ulshafer, Bronson decided to set the audacious goal of becoming a national leader in healthcare quality. The first response from the hospital board was incredulity, but they eventually were persuaded that the goal was attainable. Strategies and plans were developed that culminated in Bronson’s receiving the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awardz7 in 2005 recognizing its place of leadership in healthcare quality.8 Setting BEHAGS can be an important part of creating lasting competitive advantage. Larry Page, cofounder of Google, has said that it “is often easier to make progress on [BEHAGS]…since no one else is crazy enough to do it, you have little competition.”9

Strategic Deployment

Strategic deployment is often a problem area for organizations. All too often, more attention is paid to strategic planning than to implementing those plans. Without effective deployment, the strategic plan becomes an empty document. Effective deployment involves sharing the plan with all members of the organization with the intent of obtaining buy-in. Projects to effect the plan are initiated with responsibilities, resources, milestones, and due dates assigned.

Responsibilities. The individual or group responsible for the development and execution of each project must be delineated. Those responsible must be accountable for the success or failure of the project. This is much easier to achieve when those responsible for the results of the project have bought into the objectives and have also been involved in the development of the project from the beginning.

Resources. It is the responsibility of management to secure and allocate the resources necessary to deploy the strategic plan. The first resource that comes to mind is money. Certainly, appropriate levels of funding are essential; however often time is the most scarce resource. This fact is frequently ignored as companies assign more and more responsibilities to their best people in addition to their “regular work.” “Follow the time” is as important as “follow the money” in determining what is really important to management. Underfunded projects assigned to overworked employees cannot be that important to the organization.

Milestones and due dates. It is important when initiating projects to deploy the strategic plan that periodic milestones be established at critical points where progress will be reviewed. This provides the opportunity not only to compare actual progress to plan but also to make necessary changes to resources, scope, strategies, and final due date. Establishing a due date at the beginning of the project not only establishes a target, but also provides a motivation to complete the project on time. The establishment of milestones and due dates should always be a collaborative effort involving organizational managers and project managers and participants.

Strategic Evaluation and Control

Evaluation and control gathers, analyzes, and disseminates data in order to assess the effectiveness of strategic deployment. Another aspect of this element is to continuously monitor the internal and external environments for changes that might render aspects of the strategic plan obsolete. This means that strategic planning cannot be a once a year endeavor. It must be a continuous process with strategic plans revised and updated as new information is obtained. Through this process the organization acquires the management agility to be able to respond more rapidly to opportunities and threats, and to address weaknesses and capitalize on strengths than competitors. Obtaining the necessary information to become an insightful and agile organization requires thinking on a higher level.

The Problem with Too Narrow a Focus: Moving Up a Level

The first level of thinking results in a narrow definition of the business an organization is in and the environment in which it exists. This is useful—particularly for operational management. The focus of this level of thinking is on things such as how do our outputs compare with our competitors, how satisfied are our customers, and continuous improvement efforts to optimize performance and efficiency.

Moving up a level requires an organization to take a broader view of its business and its environment. At this level an external environmental scan looks beyond the obvious and explores the unknown—including assessments of new technologies that could potentially affect the organization, and organizations that are not currently competitors, but which could conceivably become competitors in the future. Often these potential opportunities and threats are not obvious, so insight is required in order to recognize them early.

Organizations often increase the risks to which they are exposed by too narrowly defining their external environment. The result is an environmental scan that might perfectly define the nearby trees but entirely omit a description of the forest. This happened to the railroads after World War II when they described their environment as the railroad business. Had they described their environment as the transportation business, they would not have underestimated the effect of better highways and more extensive air transportation options on their core business. This type of thinking is what we mean by “moving up a level.”

What is the difference between an opportunity and a threat? Often it depends upon whether you or a competitor acts upon it. Early in its development, Kodak did not perceive digital photography as an opportunity, but as a threat. Other organizations not involved with emulsion-based photography perceived it as an opportunity. As a result Kodak had to play catch up in the digital photography field and never attained the same position of market leader as it did in the emulsion-based photography field.

Narrowly focusing on immediate competitors when scanning the external environment can result in missing entirely the true threats (opportunities?) that may fundamentally affect the organization. The slide rule manufacturers of the 1960s defined their business as slide rules rather than portable number crunching. They completely missed the threat that came from the electronics industry (pocket calculators) which put them out of business. For a mechanical slide rule manufacturer to be able to detect a threat (opportunity?) coming from the electronics industry is not easy. It takes insight to do that, and without that insight, the future of the organization could be in jeopardy.

Insight is required when doing the environmental scans in order to be able to sift through the masses of information to perceive the real opportunities and threats and indeed to turn threats into opportunities (Figure 5.2). The insightful leader will continually ask Barker’s10 fundamental question: “What is impossible to do today, that if it were possible, would fundamentally change the way we do business?” Had Kodak asked this question much earlier, it might have been a leader rather than a follower in the digital photography market.

Figure 5.2. The importance of identifying the true threat.

The Paradox of Failure: Why Some Types of Failure Should be Encouraged

We all have to decide how we are going to fail…by not going far enough or by going too far.

—Sumner Redstone

Most great people have attained their greatest success just one step beyond their greatest failure.

—Napoleon Hill

Quality expert, W. Edwards Deming included “Drive out Fear” among his famous 14 points for management. Fear of failure can be a significant inhibitor to creative thinking. The fear can be self-induced (lack of self-confidence) or organizationally induced (fear of punishment for failure). The best organizations encourage failure. Author Josh Linkner reports on a software company that issues each of its employees two “I screwed up” cards each year. At their annual reviews with their bosses, employees who do not use both cards are scolded.11

One of the authors remembers how his direct reports at a staff meeting looked surprised when he insisted that the R&D Director should be making more mistakes. The consternation was because he had just finished encouraging the Operations Manager to find ways to make fewer production errors. There isn’t really as much of a double standard at work here as it might seem. It is all about making the right kind of mistakes.

So, what is the right kind of mistake? Both Operations and R&D should be encouraged to make some mistakes. Mistakes are inevitable when trying new things and exploring new ideas. But both should strive to eliminate mistakes due to carelessness. It is in the nature of R&D to make more mistakes than Operations because R&D should be plowing new ground to develop new products, processes, ideas, and technologies to propel the organization to the forefront of its business. It is always risky to venture into the unknown, but that is where R&D will find the next great idea—along with many not so great ideas (mistakes) too.

Any mistake can have at least some favorable consequences if handled correctly. At the very least mistakes can provide an understanding of an area where a process needs to be improved. The first rule about driving out fear is to be sure that all mistakes are reported. Fearful employees tend to hide mistakes, which often compounds the detrimental effect of the mistake. When mistakes are reported, any corrective action necessary to minimize the impact of the mistake should be taken as soon as practicable. Then an insightful organization will set about the process of determining what can be learned from the mistake. This may involve such techniques as root cause analysis or failure analysis.

Chance favors the prepared mind.

—Louis Pasteur

Understanding is usually sufficient to find the root cause of a mistake or problem and to take the appropriate corrective action. Insight is required in order to turn some mistakes into serendipitous opportunities to make dramatic improvements or new discoveries. Art Fry developed Post-It Notes at 3M during the 1970s. He had heard of a colleague’s failure. The colleague was working on new adhesives and the most current experiment was not sticky enough. A favorite saying of Fry’s is “One person’s mistake is another’s inspiration.” Hearing of the failed adhesive, he applied it to small bits of paper and used them as bookmarks for his church choir’s hymnals that could be easily removed and reused. He also used these bits of paper with the failed adhesive to make notes on reports, and soon many at 3M were requesting samples. In a clever bit of test marketing, 3M provided samples of the prototype Post-It to the secretaries of top executives. Soon employees in those companies were asking where these things came from and it was apparent that 3M had a promising new product—all because one researcher failed in his efforts to make a new adhesive and another had the insight to see the potential of the mistake. None of this would have happened had the researcher who developed the adhesive tried to hide his failure.12

A knowledge management (KM) system can be very effective in helping to share information about failures throughout the organization. A KM system is designed to collect, store, organize, and disseminate an organization’s experiences, insights, understanding, and indeed its mistakes to facilitate organizational learning and effectiveness. Not only can this be useful in preventing making the same mistake many times, but it can also be helpful in providing inspiration (a la Art Fry) to someone else in the organization.

One of the authors observed an organization which had an established innovation management program. One step in the program was to vet all of the ideas submitted and to select those which would be recommended for further evaluation. The discarded ideas went into the organization’s KM system. Periodically, the organization would revisit those discarded ideas and they reported that more than once, one of those discarded ideas turned out to be the beginning of a major innovation.

Reacting to Failure

Extreme care should be taken to be sure that the reaction to failures is productive. Even in the best of cases, failure can be a source of embarrassment to an employee. So, in addition to establishing a culture where failure is acknowledged as a learning opportunity, managers should be sensitive to employee feelings on a case-by-case basis. In no case should an error be hidden, but sometimes it is best to address the error in private rather than in public. To do otherwise in these cases would have the effect of driving some errors underground.

Reward systems should be designed so that stretching and failing is rewarded as is stretching and succeeding. The consulting firm Maddock Douglas gives an annual Fail Forward award, which is designed to celebrate “endeavors both ambitious and disastrous.” Last year, a designer at the firm won for an unorthodox publication design that wound up laying waste to the production schedule and resulted in a costly error. “It was a total embarrassment,” said president Viton. “But she was trying to do something new and different and better. She went for it, and she won an award for it.”13 This approach acknowledges the failure and its consequences while clearly sending the message that this type of error is expected when employees respond to the organization’s exhortations to stretch for BEHAGs.

Managers are Not Just Scientists and Engineers at a Higher Organizational Level

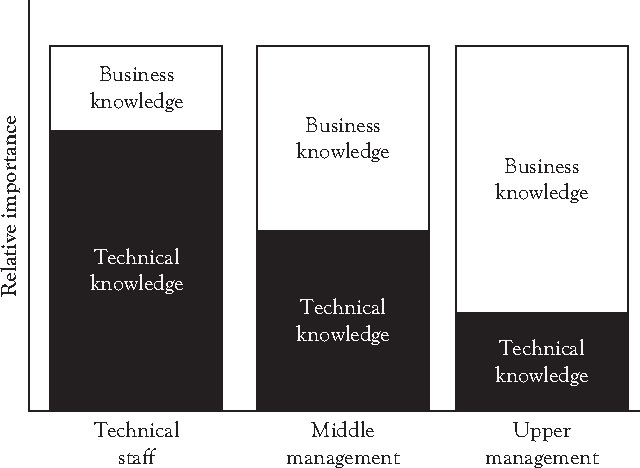

An entirely different skill set and way of thinking is required of leaders and managers than of technical staff. Evidence of this includes the ready availability of courses such as “Transition from Technical Expert to Effective Leader” offered by the University of Notre Dame and books such as Michael Aucoin’s From Engineer to Manager: Mastering the Transition.14

Technical staff, even at the insight level of awareness, generally takes a narrower view of things than managers. Insightful chemists will develop and test new hypotheses in chemistry that may lead to new knowledge and new product opportunities. Insightful engineers will work to learn as much as possible about engineering theory and processes of possible use in their industry and work to develop new processes that may lead to breakthrough improvements. These insightful technical specialists may actually be encouraged not to be overly concerned with business factors such as potential applications, economic returns, or implementation issues in their initial work because that might inhibit their creativity.

Managers, on the other hand, must consider all of the possible implications of the activities under their control—business factors as well as technical factors. This is not to say that technical staff should not concern themselves at all with business factors. It is just that these business factors are not their primary focus while they are the primary focus of managers.

Often high performing technical staff members are selected for promotion to management. In some cases, their managerial performance is not up to the high standard they set when working in their technical field. This is usually not the result of the Peter Principle15 effect where they have been promoted to their level of incompetency because these are generally very bright people used to performing at the highest levels. Rather it is a result of their knowing what they know and not knowing what they need to know in order to be successful managers. Most would agree that a strong grounding in the science and technology of the organization is very helpful if not essential to managers. But more is required of managers. Figure 5.3 shows a representation of the relative importance of technical knowledge and business knowledge for technical staff, middle managers, and upper managers. This is a general representation—the actual ratios vary from situation to situation.

Figure 5.3. Relative importance of business knowledge and technical knowledge for technical staff versus management.

The classic view of management is that it consists of four functions: planning, organizing, leading, and control. Insightful managers must master the theories, practices, and interactions underlying these functions as well as the technologies of the organizations they manage. So, when very successful technical staffers move into management, a new skill set must be mastered in order for those new managers to continue to perform at the highest level.

In management the criteria by which performance is judged are quite different from those used in technical work. Technical employees are often judged by measures that include patents awarded, new products developed, problems solved, and projects completed on time and on budget. Managers tend to be judged by broader measures such as profitability, return on assets, employee turnover, and various quality measures. It is important to provide training and clearly defined performance measures against which the newly promoted manager will be judged.

Reward systems should be designed with great care to assure that behavior and results that are desired are encouraged by the reward system. There is a famous article by Kerr16 “On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B.” One of the authors observed the effect of a poorly thought-out reward system in person. The organization wished to reduce the cost of purchased raw materials. It established a reward system for the purchasing manager that provided a bonus based on reduction in total dollars spent on raw materials as a percentage of sales. The result was a significant reduction in the performance measure, but a significant increase in the total costs because the cheaper materials the manager purchased were significantly lower in quality and increased production downtime, in-process waste, quality rejects, and customer returns.

While there are many theories of motivation, the behavioral school views reward systems as being based on Skinner’s17 reinforcement theory and Vroom’s18 expectancy theory. Reinforcement theory is a theory of motivation that is behaviorist in nature and proposes that reinforcement conditions behavior. It concentrates exclusively on what happens to people when they take some action. Therefore, reward systems should be designed to consistently reinforce desired behavior. Expectancy theory is also a behaviorist theory which argues that the strength of a person’s tendency to act in a particular way is determined by three things:

- Expectancy = Expectation of receiving a specific reward.

- Instrumentality = Probability assigned by an individual that a particular performance will lead to a specific reward.

- Valence = Value an individual places on a specific reward.

Putting Skinner’s and Vroom’s theories together argues that consistently provided rewards can influence behavior, but in order to do so employees must expect that certain behavior has a high probability of being rewarded and the reward must be valued by the recipient. And as Kerr points out, you must be careful that there is consistency with what you “hope for” and what you design the system to reward.

Intrinsic motivation is motivation that comes from within and does not rely on extrinsic rewards. Insightful individuals tend to be intrinsically motivated. Selecting high-achievement individuals for employment, providing them with meaningful work and autonomy, and a supportive organizational environment are important ways that organizations can benefit from intrinsically motivated individuals. While in the pure sense, no extrinsic rewards are required for intrinsically motivated individuals, in practice the motivation of these individuals can benefit from reinforcements such as recognition and praise.

Frederick Hertzerg,19 among several classic theorists, proposed that certain factors can create job satisfaction and thus encourage intrinsic motivation while others can at best only create no dissatisfaction. The former he called motivators; the latter he called hygiene factors. Motivators include achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, growth, and advancement. Increasing these factors leads to greater satisfaction and motivation. Hygiene factors include salary, quality of supervision, work conditions, and organizational policies. The best that increases in these factors can achieve is elimination of job dissatisfaction.

Hertzberg’s theory provides a basis for understanding how to create an environment that reinforces intrinsically motivated individuals. Take care of the hygiene factors by providing good working conditions, a fair salary, and good supervision to assure the environment is not de-motivating. Provide meaningful work, autonomy, recognition, and opportunities for growth to provide an environment within which intrinsically motivated individuals can thrive. As a mentor to one of the authors once advised, to achieve success as a manager, select good people, provide meaningful work and a supportive environment, then stay out of their way.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have discussed the need to take an insightful approach to strategic management—one that takes a broader view of the environment than is typical. Insightful strategic planning must include some BEHAGS among its goals in order to create radical improvement. BEHAGS must be supported by a risk tolerant culture. Failures are inevitable when pursuing BEHAGS, and indeed the right kind of failure is to be encouraged. While insightful strategic planning is the first step, it is useless unless followed by effective deployment and evaluation and control.

The best technical staff member will not automatically be a high performing manager because different skill sets are required for technical work and managerial work. Training must be provided to enable technical staff to make the transition to management level positions. In designing reward systems for managers, care must be taken to ensure that rewards that are valued are consistently given for what you carefully design the system to reward.

Insightful organizations:

- Incorporate quality into their strategic management process take a broader view of the organization and its environment, and is unafraid to make BEHAGS a part of the strategic plan. How does your organization define its mission, vision, and environment? Is quality an integral part of your organization’s strategic plan? How many of your organization’s strategic goals could be classified as BEHAGS?

- Adopt a different attitude toward failure. What is the risk tolerance of your organization? Does your organization encourage the right type of failure? How does your organization react to “stretching and failing”? Is your organization’s reward system aligned with its attitude toward risk?

- Recognize that insightful technical employees are not automatically insightful managers. Does your organization recognize the different skill set required by managers and provide technical employees promoted into management with appropriate training? Is your organization’s reward system aligned with the mission and vision of the organization?