This chapter aims to introduce you to some of the activities that you need to know about in starting up and managing a photographic business. An attraction for many people in choosing to work in photography is the freedom and flexibility offered through self-employment; however, it requires a certain degree of skill and knowledge to make a successful living from working in this way, as you do not have the protection in terms of employment laws or a guaranteed regular income, paid annual leave and other employment benefits offered by working for an organization. It may be that at certain times in your career, you may be employed by an organization as a staff photographer; or you may do both, combining part-time work for an organization with your own business. Additionally, depending upon the type and size of business, you may employ others to work for you. Business practice varies with the nature of the work, and the location, but there are certain aspects common to all types of photographic practice that it is important to be aware of, to protect yourself and the people working for you, to protect your work and your equipment and of course to ensure that your business runs smoothly and is viable. This chapter aims to identify these areas and give a general overview. It is important that you find out the specifics for your own practice from relevant sources relating to your area. There are many useful publications covering business practice in photography in more detail. Often photographic associations will produce their own publications covering practical and legal considerations for a particular type of photography; therefore these can be a good starting point.

Starting out

Most photographers do not rely solely on freelance work until they have established themselves to some extent. Initial photography jobs may not be paid, but used to build up a portfolio. This requires that you have an alternative source of income to fall back on as you begin to work in photography. These may be activities unrelated to photography, but it makes more sense to begin working in an image-related area if possible, simply because it can provide valuable insight into the industry.

Starting gradually also allows you to build up some capital, vital at the beginning, as, depending upon the area that you are working in, the nature of commissioning means that for some jobs you may not be paid for several months, and you will need to be able to cover your overheads and living expenses in the meantime. The alternative to having your own capital is a bank loan and for this you will need a well-defined business plan. Either way, you need to have identified various aspects before you begin, such as the type of work you will be doing, format and equipment required, how you will sell the work, your market and any additional start-up costs, such as rental of equipment or premises.

Working in the industry, for example as a photographer’s assistant, also allows you to begin to establish a network of useful contacts. It is important to remember that, vital as self-promotion and marketing is in running a successful business; the people that you get to know are also a key resource. The majority of photographic industries, whatever the type of imaging, are built on communication through networks and via word-of-mouth, from those commissioning, buying and using the images, to the photographers themselves, the people working with the photographers (assistants, models, retouchers) and all the companies supplying the industry with services, materials and equipment. Establishing relationships with the organizations and people that will be relevant to your practice will save you huge amounts of time and money in the long run.

As well as networking, working in the industry before going completely freelance allows you to test and develop your skills. For this reason, many photographers start out by assisting other photographers, learning from the way they work and using the opportunity to practice and improve in their use of equipment, as well as learning about the way the business operates.

Working as an assistant

The tasks involved as a photographer’s assistant will vary depending upon who you are working for and the type of work they do, particularly whether it is on location or mainly studio based. It may involve anything from checking equipment, loading film, downloading images or setting up lights, to maintaining studios, meeting and greeting clients, and sending out invoices.

You will need basic photographic skills and an understanding of the different formats. Having knowledge of digital technology and some basic retouching skills in Adobe Photoshop are also useful, particularly if the photographer has made the complete transition from film to digital. Being motivated, reliable and able to learn quickly are often more important qualities than having advanced knowledge of, for example, lighting techniques, which can be picked up as you go along. Many assistants begin when they are still at college. Volunteering to work for an initial few days for free, or arranging a week’s work experience can be a way of getting your foot in the door. If the photographer likes you, they may offer you more days or even something more permanent. Photographers may be happy to take on relative beginners, as long as they show that they have the right attitude, are willing to learn and get on with them – after all that is how many of them will have started out.

Often photographic associations have systems to put photographers in touch with prospective assistants, or they may advertise assisting jobs, which may be one-off or more long-term. Generally the work will be paid according to a day rate and based on your level of experience. The rate of pay also depends on the type of work. Advertising photography, being the most lucrative area, pays much better than most other areas. It is worth finding out what the going rate is from other assistants or relevant associations and agreeing this beforehand.

As an assistant, you will usually be working on a freelance basis and will work as and when the photographer needs you. This requires that you are flexible and prepared for quiet periods and a relatively low income. However, this allows you the freedom to use your spare time to work towards your ultimate goal of working as a photographer rather than an assistant. Putting together a portfolio is not a one-off job; you should be constantly reviewing and updating it. Fashions in photography change, as does the way in which the work is presented. Looking at other people’s work, fellow assistants, photographers and exhibitions will provide inspiration. You may decide that you need more than one portfolio, depending upon who it is aimed for, or you may have a pool of images (which you can constantly add to) that you can chop and change to tailor the portfolio to the person you are showing it to.

As an assistant you may have opportunities to use or create images which you will then put in your portfolio. It is vital if you are using someone else’s equipment that you have the agreement beforehand and are clear about the terms of use. The same rules in terms of legal requirements and insurance apply as if you are working as a photographer, particularly governing working with other people. You will need to make sure that you are adequately covered in terms of Employers’ Liability insurance in particular. See later in this chapter for more details. If you are assisting a photographer in an organization and are using their equipment and facilities, you must also be very clear about copyright ownership. Occasionally you will come across an organization that specifies in their contracts that they own the copyright of any images taken using their resources; it is obviously best to avoid this, as you need to maintain your own copyright wherever possible.

Because assisting work varies so much, it is difficult to generalize about the business aspects, but this is the time to get into some good habits, as these will be just as useful when you are working as a photographer. Basic book-keeping, where you track jobs, invoices and expenses is a fundamental skill. Keeping records of jobs, writing things down and obtaining confirmation are also important and will make your life much easier, as you will see, particularly if anything unexpected happens. At the very least, you should become accustomed to ensuring that you clarify the terms of a job before you start; the dates, length of time and payment of fees and expenses. This means that both you and the photographer will be clear about what you expect from each other, misunderstandings are less likely to happen and you are more likely to be booked again.

Becoming a photographer

Working as a freelance photographer

Whether you start out as an assistant or work in another area as you are establishing yourself, the process of becoming self-employed and supporting yourself through your photographic work may well take several years. Building up a client base may require that you begin by taking on some jobs for free. This should not be viewed as a waste of time however; you never know when you are likely to come across someone who really likes your work and not only re-books you but recommends you to someone else. You will also be producing work for your portfolio as an ongoing concern.

During this time you will need to work out what area of photography you want to work in. From this you can perform a skills audit, identifying what you need to know and where you need to improve. This will also identify how you go about obtaining work and finding clients.

For example, the skills required to become an architectural photographer are highly technical, such as the use of larger format equipment, the ability to light interiors and create mood. The photography may be either advertising or editorial and you will need to network with people already involved in these areas, contact organizations and agencies requiring these sorts of high-quality images and probably to assist photographers also working in architectural photography. You will need to be taking your portfolio to art directors and picture editors for relevant publications. How you go about this will depend upon the way the industry works in your geographic location.

The skills required by a photojournalist are somewhat different however. This type of photography is less structured and more immediate. It tends to be predominantly 35 mm format or equivalent and there is a much greater emphasis on candid images, seizing the moment and being in the right place at the right time. Where editorial and advertising photography will often involve an entourage of people in any one shoot, the photojournalist works mainly on their own. There is not the time available as there is in more formal photography, for images to be retouched, possibly by someone else. The photojournalist these days works mainly using digital equipment from capture to output, with a laptop to retouch the images and transmit them wirelessly as important a part of their everyday kit as their camera. The skills required are more geared towards this way of working. This type of work requires them to think on their feet and to be able to constantly adapt as a situation changes or a news story breaks.

You will find that the conventions for getting your work seen differ depending upon where you are and what type of work you are doing, either as a result of particular legislation applying to the industry but also to do with the level of competition for that type of work. For example, the highly competitive environment in a city such as London or New York means that you may not have face-to-face access to picture editors and will have to leave your portfolio for them to have a look at, in the hope that something in it will catch their eye and they will call you back. In a smaller city elsewhere in the world, things may work differently, with a much more personal approach and the ability to sit down and talk through your portfolio with the relevant people. Any type of photography that is ultimately going to be published in magazines or newspapers is likely to require that you seek out and get your portfolio seen by the right people. However, the area you decide to specialize in will define the people that you need to get to know and the way in which your work should be presented. Presentation is extremely important if the final output is in advertising or something similar.

Figure 15.1 Photographers await Sir Elton John and David Furnish to leave Windsor Guildhall after their civil ceremony, Wednesday, 21 December 2005. Image © James Boardman Press Photography (www.boardmanpix.com). Freelance press photographers often go out on speculative shoots, covering local events or current news items. They will then email the image to all newspapers for a prospective sale. There is a lot of competition when working in this way – it will often depend upon who gets their image of an event to a picture desk first.

For photojournalism, however, the content and meaning behind the images, and the speed at which you get them seen is more important. News photography in particular relies more and more on the publication being the first to obtain the rights to the image. Many photojournalists will go out on speculative shoots, following a particular news story, trying to get a decent image and then being the first to get it to a news desk (Figure 15.1). You may therefore first get noticed by a picture editor through a specific image that has been emailed rather than through a portfolio. A lot of money can be made if the image is covering an important news item, but obviously these types of images have a short shelf life. If someone else gets the image to the picture desk first, even if it is of lower quality or not as good a shot, and that image is published, particularly on the web, then it may render your image redundant, however good it is.

Working as a staff photographer

An alternative to starting out on a self-employed basis is to become a staff photographer for an organization. There are a number of areas where this is more common, for example, local newspapers will often employ photographers on a more permanent basis. Other fields include forensic photography, for example, or medical photography. There are advantages to starting out in this way, as the organization will offer the same rights to a staff photographer as to any other employee. Although you sacrifice the freedom and flexibility of freelancing, you are afforded protection in a number of ways, and have paid holiday, annual leave and a steady income. Additionally, the organization will often buy your equipment for you, which can be a godsend if you require expensive digital kit. Your overheads will also be covered, for example, materials, and communications costs; in some cases a company car may even be provided.

This all sounds rather comfortable, but employed photographers do not tend to have the same earning capacity as freelancers. Another key issue is that of copyright. You will be tied in by a contract and this may well state that the organization not only owns the copyright on any images that you take for them, but also on any images that you take for yourself using their equipment and facilities. In the more scientific fields however, you may not have any alternative as there may not be the option of working as a freelancer; the organizations simply do not work like this.

The issue of whether you want to be employed or freelance is therefore another consideration when deciding on the area that you are going to work in. Certain specialisms in photography rely solely on employed photographers and this may be something that you are happy to do, either because you appreciate the security, or because you are very clear that this is the type of photography you wish to do. Alternatively, you can choose to work as a staff photographer as an intermediate stage to become freelance.

To summarize, there are a number of aspects common to the process of becoming a working photographer, once you have decided what type of photography you are going to work in. These include purchasing equipment (unless working as a staff photographer), gaining experience in your chosen field, identifying and obtaining required skills, creating and updating your portfolio and getting your work seen by the relevant people, either future employers or future clients. Although the details may vary, the qualities required are similar: to work in photography, whatever the field, you need to be highly motivated, organized and creative both in your work and in your approach to business. You also need patience and persistence. Although technical skills and creativity are of primary importance, personality plays an essential role in achieving success as a practising photographer. Sheer grit and determination may be necessary at times to ensure that your work gets seen. You must believe in yourself and be prepared to market yourself and your skills. You must also be prepared for knock-backs; it may take some time before you start to sell your work.

Running a business

To run a photographic business successfully you have to master certain management skills, even though you may work on your own. Some of these activities are specifically photographic but most apply to the smooth running of businesses of all kinds. If you are inexperienced try to attend a short course on managing a small business. Often seminars on this theme are run by professional photographers and associations. There are also many user-friendly books and videos covering the principles of setting up and running your own business enterprise.

Many photographers choose to operate their businesses as sole traders. This is the simplest method and offers the greatest freedom. The photographer interacts with others as an individual, has sole responsibility in making decisions, but also personal liability for debts if the business fails. It is vital if working in this way that you separate business from personal financial transactions, having a separate business account. It is also important to ensure that business costs are met before personal profit may be taken. When working as a sole trader, discipline is necessary in keeping track of income and expenditure. Book-keeping need not be complicated, particularly if you hire an accountant to do your end-of-year returns, as long as you set up some sort of system and use it consistently.

An alternative method of business set-up is some sort of partnership. This can be a useful way to share the resources and start-up costs. The way in which the industry has changed since the use of the Internet and digital technology have become more widespread, means that it can be useful to offer a range of services alongside photography, such as the design of graphics or web-pages, and the scanning, retouching and compositing of images. Some photographers have expanded their skills, meaning that they can offer some of these additional services themselves, but a partnership can be a useful way for several freelancers with different skills to work together. In partnerships, the partners are jointly liable for debts. This can be an advantage, as the pressure is taken off the individual; however it is important that all partners are very clear from the outset on the terms of the partnership and responsibilities involved in the business. The business relationship should be defined legally and ideally partners should try to discuss possible issues that might arise and how they will be dealt with, before the business is set up.

The most formal method of running a business is to set it up as a company. This is less common; it tends to happen more with businesses with a higher turnover. Advantages include removal of individual liability should anything go wrong, and the fact that the business will remain, should an individual choose to leave (which can be a problem in less formal partnerships). However running a company is significantly more complex; more administration and organizational procedures are involved and it may be more laborious and time consuming to make long-term decisions.

Book-keeping

Book-keeping fundamentally involves keeping a record of any financial transactions to do with the business, incoming or outgoing. However the photographer chooses to operate their business, book-keeping will be a fundamental part of the day-to-day management. Many photographers, particularly those working as sole traders, will manage the process of book-keeping themselves, but pay an accountant to deal with their books at the end of the year to calculate their tax returns. This may sound the dullest aspect of professional photography. But without well-kept books (or computer data) you soon become disorganized, inefficient and can easily fall foul of the law. Good records show you the financial state of your business at any time. They also reduce the work the accountant needs to do to prepare tax and similar annual returns, which saves you money.

Having set up a separate business bank account, it is necessary to keep a record of income and expenditure, have a method for tracking and archiving invoices and somewhere to keep receipts. The process of recording can be performed in some sort of accounting software, but can be as simple as a spreadsheet on which income and expenditure are entered on separate sheets on a regular basis. A filing system can then be set up corresponding to this, to store the hard copies of receipts and invoices, to be passed to the accountant at the end of the financial year.

A large aspect of your book-keeping will be to record individual jobs. You will need some sort of booking system which may be separate to your accounts, but for financial purposes, you need to record all the jobs in terms of their invoices. The expenses associated with each job should in some way be linked to the invoice, both in software and in hard copies. The client will usually be charged for the majority of expenses (such as materials, processing, contact sheets, prints and taxis) associated with a job. Expenses will appear as money coming into the account but they are not counted as income as you will have spent money up front for them and are simply claiming it back from the client, so it is important that they are identified and not taxed.

When you raise an invoice, you should record the invoice number, client name, description of the job, date, amount and expenses. When the invoice is paid, you should then identify it as paid in your invoice record and include the date, amount and method of payment. Alongside this, you need a receipt book, in which to record payments received from customers. After giving the customer a receipt, record the receipt number in the invoice record. You may prefer to create your own receipts electronically, but must make sure that you back them up. Receipt books are usually simpler as they contain carbon copies and keep all the receipts you write out in one place.

Alongside your computer records of invoices, you should also keep hard copies of invoices in a filing system. A simple method can be to file all information from the job together, which makes it easy to access and means that you do not have many different filing systems. You could for example, include the original brief (if there was one) and any notes you made at the time, confirmation from the client (printed out if by email), delivery note, model release forms, contract, copies or record of receipts (originals should be kept elsewhere, as they will need to be submitted to the accountant) invoice and captions. Jobs can then be filed in date order and possibly by client if they regularly commission work from you. If you then have any queries you can go back and see all the details in one place.

You should also keep a separate record of outgoings in terms of purchases of goods and services. You can simply list all suppliers’ invoices, with a note of what they are for, the date and when and how they are paid. You can link this to your depreciation record (see below).

For small purchases that you may buy from time to time, for example stationery, which are not to be associated with a particular job, it is useful to operate a petty cash tin, in which you keep a cash float. Each time you pay for something from the tin, you place the receipt in the tin. When the float is low, you can add up all the receipts on a petty cash sheet and keep them all together, then topping up the float to its original amount. A petty cash system saves cluttering up your main records with small entries. It also points up the vital need always to retain every relevant receipt – big or small.

You also need to keep records of all your main items of equipment. This forms an inventory (against fire or theft), but more importantly you can agree a ‘depreciation’ rate for each piece with your accountant. For example, a camera may be given a reliable working life of five years, which means that its value depreciates by a set amount each year (effectively this is the annual cost to your business of using the camera, and part of your overheads when calculating trading profits for tax purposes).

Insurance

Because photography involves such expensive equipment, you will undoubtedly have given some thought to equipment insurance. It is important to check your policy very carefully, to ensure that it covers, for example, equipment transported in a car, and overseas. You should also make sure that you are clear about whether it involves new for old replacement of equipment. The insurance should be enough to cover the value of your equipment, and you should make sure that the maximum for a single item of equipment is adequate and that the single item excess is not impractical for making a claim. It is probably best to seek out a company specializing in insurance for photographers, as they will tend to have policies tailored to the high value of individual pieces of equipment. Standard contents insurance is usually inadequate for these purposes.

There are legal requirements for a working photographer (or assistant) to have a basic level of certain other types of insurance, to protect the business against claims for damage to property or people, or negligence such as mistakes in or loss of images leading to additional expenses for clients. These will vary depending upon where in the world you are working, you can assume that similar rules will apply, but must check the legal requirements for the country in which your business is registered. The following is an example of some of the relevant insurance policies available in the UK. It is not exhaustive; check Photographers’ Associations in your field for more details.

Employer’s Liability insurance

This is a compulsory insurance in the UK, if a photographer has anyone working for them, even if they are not being paid. If an employee has suffered an injury for example, while working for a photographer, and the courts decide that the photographer was negligent and therefore liable, then the Employer’s Liability insurance protects the photographer and will meet the costs of the employee’s claim. This insurance covers death, injury and disease.

Public Liability insurance

Similar to the Employer’s Liability insurance, this covers property rather than people and protects the photographer from liability for loss or damage of property, and injury, disease or death of a third party (who is not working for them).

Professional Indemnity insurance

Although optional, this is one of the more essential ones when working professionally, as it protects against claims of professional negligence. These may be about very minor things, but can cost a business a lot of money. Examples include infringement of copyright, mistakes leading a reshoot being required, loss or damage of images, etc.

Charging for jobs

Knowing what to charge often seems more difficult than the technicalities of shooting the pictures. Charging too much loses clients; charging too little can mean periods of hard work for nil profit. It is not seen as good practice to drastically undercut your contemporaries; it can undermine future jobs and would not make you friends. The amount to charge will depend fundamentally on the type of work you do and who it is for.

If the work is commissioned, then you will be agreeing a price up front. Advertising is by far the best paid, but the amount will depend very much on how big the job is, the type of media and the circulation (as well as your reputation of course). Press photography varies widely – the sky is the limit if you are covering a big story and have obtained an exclusive image which you are able to tout to the highest bidder. Editorial work tends to be more poorly paid, sometimes a fifth or a tenth that of standard commercial rates. For all of the above areas, it will depend fundamentally upon who is buying your image and what the convention is in the region that you work. Newspapers and magazines often have a set day rate, which may be negotiable, but this will be the key-determining factor. If you tend to do more commissioned photography for individuals, for example photographing social events, then it is more common for you to set your day rate as a starting point and the client to then negotiate with you from that.

Working out your day rate

It can be helpful to find out what your competitors are charging before you start and it is useful to be flexible; you may have different day rates for different types of jobs, depending upon their complexity, and also for different types of clients. You may not always work for your day rate (particularly when working for publications that specify their own day rates and are relatively intransient in this), however it is important to have a rate in mind during negotiations which makes sense for you and your business. It is also an important benchmark for you to help in deciding when to turn down work. It may seem strange to think in these terms, but there will be some jobs where the money on offer will not be enough to cover your overheads or make it worthwhile for you. There may be some situations where you choose to take on this work, but having a day rate which has been worked out systematically allows you to identify these jobs and make informed choices about whether you take them or not. Hopefully in more cases the money offered will be higher than your day rate rather than lower.

Working out a reasonable day rate is based on costing. Costing means identifying and pricing everything you have paid out in doing each job, so that by adding a percentage for profit you arrive at a fair fee. This should prevent you from ever doing work at a loss, and provided you keep costs to a minimum the fee should be fully competitive. Identifying your costs means you must include indirect outgoings (‘overheads’) as well as direct costs such as materials and equipment hire. Typical overheads include rent, electricity, mobile phone, broadband Internet connection, water, cleaning, heating, building maintenance, stationery, petty cash, equipment depreciation and repairs, insurances, bank charges, interest on loans and accountancy fees.

You then need to work out what you want to pay yourself as a salary and any other staffing costs. You must take into account the number of days you are aiming to work over a year, including holidays and the fact that it is unlikely that you will be shooting five days a week, as you will need several days a week for the associated activities in terms of managing your images and managing your business. From this you will be able to work out how much you need to charge a day.

When it comes to costing, you base your fee on a number of elements added together

1. What the business cost you to run during the time period you were working on the job. This is worked out from your overheads and salary requirements as above.

2. The percentage profit you decide the business should provide. Profit margin might be anywhere between 15 and 100%, and might sometimes vary according to the importance of the client to you, or to compensate for unpleasant, boring jobs you would otherwise turn away.

This gives you your basic day rate. You then need to add expenses:

3. Direct outgoings which you incurred in shooting (such as the materials and storage media, travel, accommodation and meals, models, hire of props, lab services, image retouching and any agent’s fee).

Because you have paid out for the expenses already, these are not part of any profit you make and should not be taxed.

Most photographers will charge for a full day, however long the job lasts, fundamentally because some of the day will be taken up with travelling to and from the job and you will also need to allow for the time spent in related activities, such as going to pick up prints. You may choose to offer a half-day rate for jobs that are not going to take much time, but you must bear in mind that taking these jobs will usually mean that you are unavailable for other work on that day.

You will also need to consider the use of the image. It is most common for the photographer to retain the copyright and for the usage to be agreed beforehand. Usage specifies how many times an image may be reproduced, what region of the world and on what type of media. It may also determine whether the buyer has exclusive rights to the image and if so for how long. This is particularly important in news images, as their exclusive rights prevent you from reselling the image and therefore represent a loss of potential profit for you. The more that the buyer of the image wants to use it, the more you should be able to charge for it. This is an important part of the original negotiations and should be confirmed in writing (even if by email) before the image is used. For commissioned work it will usually be written into a contract. This is covered in more detail later in the chapter.

Invoicing and chasing payment

You should have a consistent system for sending out and chasing outstanding invoices as part of your book-keeping system and should check all outstanding accounts on a regular basis to ensure that you keep on top of things.

To make sure that you get paid you must first ensure that the client receives the images and a copy of your terms and conditions – this is important. When sending out images, either soft or hard copies, you should always include a delivery note. The delivery note will include your terms and conditions for the client’s use of the image. By accepting the image and the delivery note the client is accepting your terms and conditions; they will be in breach of copyright if they use the image without paying you and will be liable for legal action. If sending out hard copies, unless delivering them yourself, then use a courier to make certain that the images will be covered by insurance for their safe delivery. If using an alternative method of delivery then you should make sure that you insure the images yourself.

You can follow the images up with a phone call or email to make sure that the client has received them, and send the invoice a few days later. As well as the information about the job, you should clearly state on the invoice what your terms are for payment, i.e. how long before you expect them to pay, for example 30 days. When you get paid depends of course on who you are working for and where. Some clients may take several months to pay; this can be particularly true of newspapers in the UK, whereas others will pay promptly after two weeks.

If you check all your payments on a regular basis, it will be simple to send out monthly statements to clients with outstanding invoices. This can be backed up with regular phone calls. As long as you have clearly stated terms and conditions written on a contract and a delivery note, then you should have no problem getting payment eventually, although you should be prepared for the fact that it may involve a frustrating amount of time spent in chasing them. It is important that you do follow-up when payments have not arrived; invoices are too easily lost and some companies seem almost to have a policy of non-payment until you do chase them. It is also important to remember that the person who commissioned work from you may be far removed from the finance department and may have no idea that you have not been paid; in other words, the onus is very much on you to ensure that you get paid, not on them.

Uneven cash flow is the most common problem with small businesses. Clients (especially advertising agencies) are notorious for their delay in paying photographers. Often they wait until they are paid by their clients. It is therefore advantageous to have one or two regular commissions which might be mundane, but are paid for promptly and even justify a special discount. The length of time it can take for payment to come through is something to bear in mind when setting up your business. It may be several months before you see any money coming in and you will need to have some sort of financial safety net available to cover this period; enough to cover your living costs and overheads for two to three months at least.

Commissioned work

The majority of photographic work is commissioned, i.e. you are booked to produce particular images, rather than speculative (these are images that you shoot without being booked to do so, and then try and sell; they tend to be more common in photojournalism). Commissioned work will involve several interactions between you and the client before the job is completed and you are paid. The formality of this process will depend upon the field that you are working in and your individual way of working, but you should have a system for recording and tracking the progress of a particular commission. Some of this may involve standard forms, either yours or the client’s, whereas other aspects might be communicated by email. It is important that you keep written records and are able to easily access information relating to a particular piece of work.

Job sheets

One good way of keeping track of a job in progress (especially when several people are working on it at different times) is to use a job sheet system. A job sheet is a form the client never sees but which is started as soon as any request for photography comes in. It follows the job around from shooting through printing to retouching and finishing, and finally reaches the invoicing person’s file when the completed work goes out. The job sheet also carries the job instructions, client’s name and telephone number. Each member of the team logs the time spent, expenses, materials, etc. in making their contribution. Even if you do all tasks single-handed, running a job sheet system will prevent jobs being accepted and forgotten, or completed and never charged for.

Contracts

The agreement between you and a client should be defined by a contract, which is a legally binding document. The process of deciding on fees, terms and conditions, and usage and copyright of images is actually the negotiation of the contract. It is important that both photographer and client are clear about the terms of the contract; if either side fails to fulfil their half of the deal then the other party may pursue them for compensation through the courts. The aim therefore is to protect the interests of both parties. For this reason verbal agreements about a photographic assignment should always be followed up with something written down, even if by email; having something traceable prevents later misunderstandings. Photographers should obtain written confirmation of conversations and include terms and conditions covering details of copyright, usage, third parties, cancellation, etc. (see below). Once all the terms have been agreed and written down by one party, they should be sent to the other party, to be signed and sent back. Both sides should keep a copy of the contract.

Often publications such as newspapers or magazines will have their own standard contracts which they will expect you to work to. These may include how much they are prepared to pay you and will undoubtedly include their terms and conditions. It is important that you check exactly what is being offered before accepting a job from them, as by doing so you will be entering into a contract with them. Such contracts may or may not be negotiable; if you do negotiate, again you must ensure that you obtain the negotiated terms in writing.

Initial booking

In the beginning a booking will often be by phone or email contact, and it is at this point that you will obtain details of the images required. The client may give you a clear written briefing, or you may need to define exactly what they require in conversation with them. As well as the information about the images required, you will need to know about the date, location, format and media, and some idea of how the images are to be used, i.e. if they are to be published and if so how many times and where. You should make notes of these initial conversations and it is helpful to keep them with the other documentation for the particular job, to be easily referred to if necessary. It is also at this point that you will be negotiating your fee. It may be that the client comes with a specific budget in mind, which you may or may not accept, or that you will use the information gathered to specify the fee based on your day rate. You should also clarify issues around copyright ownership and licensing, which will have an impact on the fee charged.

Confirmation

Once the details of the job and fee have been agreed, the next stage is to confirm them in writing. It is possible that you will do this by email or more formally using a commissioning form, or commission estimate. The form should be designed so that it has spaces for subject and location, likely duration of shoot, agreed fee and agreed expenses. It also specifies what the picture(s) will be used for and any variations to normal copyright ownership. If using a commissioning form, you should also include your terms and conditions. Signed by the client this will serve as a simple written contract. The form therefore avoids difficulties, misunderstandings and arguments at a later date – which is in everyone’s interests.

Terms and conditions

Your terms and conditions should be included on the majority of the paperwork that you send out; it is common practice to print them on the back of all standard forms. These define the legal basis on which the work is being carried out; however, if the client includes a different set of terms and conditions on any paperwork they send to you, they may override yours, so this is something to keep in mind. Clients may choose to negotiate your terms and conditions; particularly in terms of copyright and usage of images: if they do not then you can assume that they are accepted and they become a part of the contract between you and the client.

Terms and conditions allow you to be specific about how you will work: they spell out details such as cancellation fees, the extent of a ‘working day’ and so on. Importantly, they should include details of copyright, usage, client confidentiality, indemnity and attribution rights. Photographic associations will often have standard sets of terms and conditions for you to use: an example set for photographers in England and Wales produced by the Association of Photographers (UK) is reproduced in Figure 15.2.

Terms and conditions

1. Definitions

For the purpose of this agreement ‘the Agency’ and ‘the Advertiser‘ shall where the context so admits include their respective assignees, sub-licensees and successors in title. In cases where the Photographer‘s client is a direct client (i.e. with no agency or intermediary), all references in this agreement to both ’the Agency‘ and ‘the Advertiser‘ shall be interpreted as references to the Photographer’s client. ‘Photographs‘ means all photographic material furnished by the Photographer, whether transparencies, negatives, prints or any other type of physical or electronic material.

2. Copyright

The entire copyright in the Photographs is retained by the Photographer at all times throughout the world.

3. Ownership of materials

Title to all Photographs remains the property of the Photographer. When the Licence to Use the material has expired the Photographs must be returned to the Photographer in good condition within 30 days.

4. Use

The Licence to Use comes into effect from the date of payment of the relevant invoice(s). No use may be made of the Photographs before payment in full of the relevant invoice(s) without the Photographer‘s express permission. Any permission which may be given for prior use will automatically be revoked if full payment is not made by the due date or if the Agency is put into receivership or liquidation. The Licence only applies to the advertiser and product as stated on the front of the form and its benefit shall not be assigned to any third party without the Photographer’s permission. Accordingly, even where any form of ‘all media’ Licence is granted, the photographer‘s permission must be obtained before any use of the Photographs for other purposes e.g. use in relation to another product or sublicensing through a photolibrary. Permission to use the Photographs for purposes outside the terms of the Licence will normally be granted upon payment of a further fee, which must be mutually agreed (and paid in full) before such further use. Unless otherwise agreed in writing, all further Licences in respect of the Photographs will be subject to these terms and conditions.

5. Exclusivity

The Agency and Advertiser will be authorised to publish the Photographs to the exclusion of all other persons including the Photographer. However, the Photographer retains the right in all cases to use the Photographs in any manner at any time and in any part of the world for the purposes of advertising or otherwise promoting his/her work. After the exclusivity period indicated in the Licence to Use the Photographer shall be entitled to use the Photographs for any purposes.

6. Client confidentiality

The photographer will keep confidential and will not disclose to any third parties or make use of material or information communicated to him/her in confidence for the purposes of the photography, save as may be reasonably necessary to enable the Photographer to carry out his/her obligations in relation to the commission.

7. Indemnity

The Photographer agrees to indemnify the Agency and the Advertiser against all expenses, damages, claims and legal costs arising out of any failure by the Photographer to obtain any clearances for which he/she was responsible in respect of third party copyright works, trade marks, designs or other intellectual property. The Photographer shall only be responsible for obtaining such clearances if this has been expressly agreed before the shoot. In all other cases the Agency shall be responsible for obtaining such clearances and will indemnify the Photographer against all expenses, damages, claims and legal costs arising out of any failure to obtain such clearances.

8. Payment

Payment by the Agency will be expected for the commissioned work within 30 days of the issue of the relevant invoice. If the invoice is not paid, in full, within 30 days The Photographer reserves the right to charge interest at the rate prescribed by the Late Payment of Commercial Debt (Interest) Act 1998 from the date payment was due until the date payment is made.

9. Expenses

Where extra expenses or time are incurred by the Photographer as a result of alterations to the original brief by the Agency or the Advertiser, or otherwise at their request, the Agency shall give approval to and be liable to pay such extra expenses or fees at the Photographer’s normal rate to the Photographer in addition to the expenses shown overleaf as having been agreed or estimated.

10. Rejection

Unless a rejection fee has been agreed in advance, there is no right to reject on the basis of style or composition.

11. Cancellation & postponement

A booking is considered firm as from the date of confirmation and accordingly the Photographer will, at his/her discretion, charge a fee for cancellation or postponement.

12. Right to a credit

If the box on the estimate and the licence marked ‘Right to a Credit’ has been ticked the Photographer‘s name will be printed on or in reasonable proximity to all published reproductions of the Photograph(s). By ticking the box overleaf the Photographer also asserts his/her statutory right to be identified in the circumstances set out in Sections 77-79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or any amendment or re-enactment thereof.

13. Electronic storage

Save for the purposes of reproduction for the licensed use(s), the Photographs may not be stored in any form of electronic medium without the written permission of the Photographer. Manipulation of the image or use of only a portion of the image may only take place with the permission of the Photographer.

14. Applicable law

This agreement shall be governed by the laws of England & Wales.

15. Variation

These Terms and Conditions shall not be varied except by agreement in writing.

Note: For more information on the commissioning of photography refer to Beyond the Lens produced by the AOP.

Figure 15.2 Standard set of terms and conditions for photographers in England and Wales. (© Association of Photographers. This form is reproduced courtesy of the AOP (UK), from Beyond the Lens, 3rd edition, www.the-aop.org).

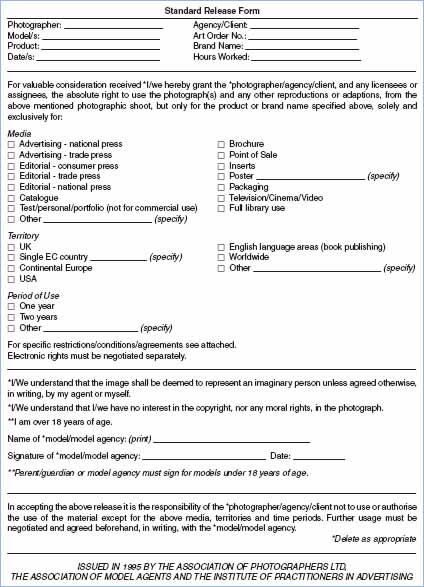

Figure 15.3 Example of a Standard Model Release Form. (© Association of Photographers. This form is reproduced courtesy of the AOP (UK), from Beyond the Lens, 3rd edition, www.the-aop.org).

Model release

Anyone who models for you for a commercial picture should be asked to sign a ‘model release’ form (see Figure 15.3). The form in fact absolves you from later claims to influence uses of the picture. Clients usually insist that all recognizable people in advertising and promotional pictures have given signed releases – whether against a fee or just for a tip. The exceptions are press and documentary type shots where the people shown form a natural, integral part of the scene and are not being used commercially.

After the shoot: sending work to the client

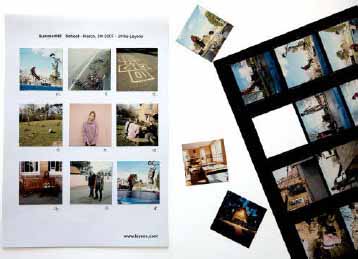

Once the shoot has been completed, what happens to the images will depend upon what you have agreed with the client. It will also be based on what type of media you work in, either film or digital. If you are using film, you may well need to send the originals to the client, unless they only want prints. The risks in terms of loss of originals are obviously greater with film, as digital images allow you to keep archived originals as well as sending them out. It is therefore important that you make sure that images are insured while in transit. Often clients will want printed contact sheets even if you are working digitally and this can be an opportunity to make a selection of the better images and present them in an attractive manner. If producing film originals, the client may want digitized versions as well. Offering image scanning as an additional service can be an extra source of income, whether you have time to do this yourself, or choose to get them scanned by a lab. For news images, it is possible that you will be sending the finished images over the Internet. It is important in this case that you ensure that the images are saved to the correct image dimensions, resolution and file format for the client. The way in which you present your work, whether transparencies, film, contact sheets or digital images is important: although they may not be the finished product, it helps to make you appear more professional, which can be important in marketing yourself and obtaining more work. An example of a selection sent out to a client is shown in Figure 15.4.

Figure 15.4 The way in which originals and contact sheets are presented to a client is important. Attractive presentation may help in both selling the images and obtaining further work from the client and may be used as part of your self-promotion. Image © Ulrike Leyens (www.leyens.com).

However you send your images, whether electronically or as hard copies, it is vital that you protect yourself against loss or damage to the images and also against clients using them without your permission. To do this you need to include a delivery note whenever you send images to another party, which can be either digital or hard copy. It should include details of the client’s name, address, contact name and phone number/email, method of delivery, date of return and details of fees for lost or damaged images. The number, type and specifics of the images should be described. Terms and conditions should be printed on the reverse and this clearly stated on the front of the note. It should have a unique number to allow you to track and file it. You should also have a specific statement regarding your policy about the storage or reproduction of the images without your permission. By accepting the images with the delivery note, the client is agreeing to these terms.

Copyright

Be on your guard against agreements and contracts for particular jobs which take away from you the copyright of the resulting pictures. This is important when it comes to reprints, further use fees and general control over whom else may use a picture. If an agreement permanently deprives you of potential extra sources of revenue – by surrender of transparency or negative, for example – this should be reflected by an increased fee. Generally, in most countries around the world, copyright automatically belongs to the author of a piece of work, unless some written agreement states otherwise, therefore you will retain ownership unless you choose to relinquish it. By including your terms and conditions with all documentation and having a written contract, you are protecting your copyright. As owner of the copyright of the image, you may choose what you do with it and you can prevent others from reproducing it without your permission.

You can assign your copyright to someone else, in other words you choose to give it up or sell it. What this means is that you will no longer have any rights to the image, any control over how it is used and most importantly, you will no longer be able to make any money from it. Bearing in mind that your back catalogue of images can potentially be an ongoing source of income it is not wise to ever give up your copyright unless you have very good reason to.

It is much more common, however, to retain copyright and agree usage of the image. This is in the form of a licence, which defines the reproduction rights of the client based on what they have paid you. The licence will specify among other things: type of media e.g. printed page, web page, all of Internet; length of time that the client may use the image; quantity of reproductions (this may be approximate, but is generally an indicator of circulation); number of reproduced editions; territory (this specifies the geographical area that it may be published in, for example, Europe only or worldwide use). The licence may be exclusive, meaning that for its duration, you may not sell the image on to anyone else and no other party may use it. It protects the interests of the client and allows them to take legal action if anyone else infringes the copyright during this period. This is quite common in press photography in particular. Once the duration of the licence has ended, the client may no longer use it. If the licence was exclusive, then at the end of its duration you will be free to sell the image on. You may choose to syndicate your image, in other words sell it on to multiple magazines or newspapers, which can be very lucrative. The client may, however, negotiate an extension or a further licence and will again pay a fee for this. Before this you may continue to use it for self-promotion, in your portfolio or on your website, but will be restricted from using it elsewhere.

There are some cases where you will have no choice but to give up your copyright, for example if you are working as a staff photographer, where it is specified in your contract of employment. Some of the large news agencies, such as Reuters or the Associated Press have also introduced contracts where they own the copyright of images and you are just paid a day rate. If they choose to use your images more than once, it may be possible to negotiate a deal for further fees.

Digital rights

Digital imaging has made enforcement of copyright more difficult, as images are much more widely distributed and it is simple to make copies of digital images, download them and store them on a computer. It is also easy to alter digital images with image processing software. Both are infringements of the image copyright. You should ensure that your images on the web carry copyright information, and that it easily visible. You may also choose to use some form of watermarking or image security software. This may involve simply embedding copyright information in the image, which will be visible if the image is downloaded, however many watermarks can be removed; it may be something more sophisticated, which prevents the user from copying or altering the image and identifies if an image has been tampered with. The issue around image altering is an important one too. It is surprising how many people working in the imaging industries are unaware that this is copyright infringement. It is quite common to find that an image submitted to a news desk by the photographer is subsequently published with significant alterations without his permission. This cannot be prevented, but you can protect yourself legally by including a clear copyright statement about reproduction, making copies and altering of the image whenever you send the image to anyone.

Marketing your business

Like any other service industry, professional photography needs energetic marketing if it is to survive and flourish. The kind of sales promotion you need to use for a photographic business which has no direct dealings with the public naturally differs from one which must compete in the open market place. However, there are important common features to bear in mind too.

Your premises need to give the right impression to a potential client. The studio may be an old warehouse or a high-street shop, but its appearance should suggest liveliness and imagination, not indifference, decay or inefficiency. Decor and furnishings are important, and should reflect the style of your business. Keep the place clean. Use equipment which looks professional and reliable.

Remember that you yourself need to project energy, enthusiasm and interest and skill and reliability. Take similar care with anyone you hire as your assistant. On location arrive on time, in professional looking transport containing efficiently packed equipment. If you want to be an eccentric this will ensure you are remembered short term, but your work has to be that much better to survive such an indulgence. Most clients are archconservatives at heart. It is a sounder policy to be remembered for the quality of your pictures rather than for theatrical thrills thrown in while performing.

During shooting give the impression that you know what you are about. Vital accessories left behind, excessive fiddling with metres, equipment failures and a feeling of tension (quickly communicated to others) give any assignment a kiss of death. Good preparation plus experience and confidence in your equipment should permit a relaxed but competent approach. In the same way, by adopting a firm and fair attitude when quoting your charges you will imply that these have been established with care and that incidentally you are not a person who is open to pressure. If fees are logically based on the cost of doing the job, discounts are clearly only possible if short cuts can be made to your method of working.

The methods that you use to market your work and the way in which it is presented will depend upon your field. But whatever area you work in, you will undoubtedly need a portfolio. In some cases this may be the only opportunity to make an impression on a potential client, as you may be asked in some cases to leave your book with them and never get the chance to meet them face-to-face. The images in your portfolio of course need to be relevant to the field you are working in, both stylistically and in substance. It is also possible that you will need to change them to suit the interests of different clients.

The content therefore needs to be carefully thought out and put together. The images must be selected with care; they should be your best pieces of work and effectively represent the range of your skills and abilities. You should not include everything: avoid duplication and streamline where possible: a smaller more concise portfolio appears more professional than one that contains every piece of work that you have done. It is also important that you include some recent work. You should review your portfolio(s) every few months and update them where necessary.

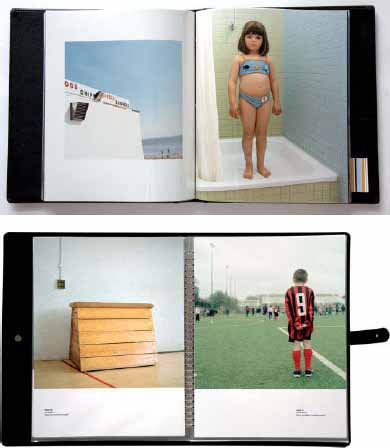

You should aim for some sort of consistency in your images, for example, grouping them according to type or content. They will look better if all presented in the same way wherever possible, on the same type of paper, similar dimensions and the same method of mounting. Paramount of course is the quality of the prints. It can be extremely useful to look at other people’s portfolios to get an idea of different styles of presentation. Figure 15.5 shows some examples.

It is also useful to include examples of work that has been published, for example, page layouts from magazines that include your images. If you have the opportunity to meet with clients then you should make sure that you talk them through your images; this is a good chance to put your ideas and your enthusiasm across.

Figure 15.5 Presentation in portfolios. Images © Ulrike Leyens (www.leyens.com) and Andre Pinkowski (www.onimage.co.uk).

If you are going to leave your portfolio with a client, include a delivery note: the same rules apply as for sending images, in terms of protecting yourself against loss or damage to your images. You may want to include other material as well, particularly if you are not able to actually meet with the client. Giving them something they can take away with them will help to remind them of you and your work; even if they do not choose to use you at this point, they may do so in the future. This may be a short CV or covering letter along with a business card. The business name, logo, notepaper and packaging design, along with all your printed matter, should have a coherent house style. Better still get a booklet or some postcards with your images and logo printed, and include these (see Figure15.6). These can also be useful to send out to ongoing clients as a way of keeping in touch and touting for more work.

Entering photographic competitions are another way to get your work seen and capture the attention of picture editors in particular. Professional competitions such as Press Association Awards (see Figure 15.7), for example, will be attended by the people buying the images. Often entries will be placed in an exhibition and in an associated book, even if they do not win an award, giving you free publicity and the opportunity to get your images seen by the people that count. The private views for these types of competitions are high profile events and a good chance to network.

As well as the other benefits that membership of professional societies and associations offers, they may be able to help to publicize your work. Most have related publications in which they showcase member’s work. They also often have sections for members’ portfolios on their websites.

Of course, the widespread use of computers and the Internet mean that a website is a vital marketing tool. It can be easy to direct someone to your work and include your URL on every email, meaning that you reach a much wider audience without the labour involved in booking appointments and carting round a portfolio. Additionally, you may present your work on CD or DVD, however this should not be considered a replacement for a portfolio; many people prefer to sit down and browse through high-quality and nicely presented prints rather than look at them on a computer screen.

Figure 15.6 Postcards and business cards can be useful marketing tools. Image © Ulrike Leyens (www.leyens.com).

Figure 15.7 Families brave the cold temperatures and snowy conditions on top of the South Downs at Clayton in Sussex. Jack and Jill windmills are seen in the background. Image included in the Press Photographers Year Awards 2006 © James Boardman Press Photography (www.boardmanpix.com).

You may choose to pay someone to design your website for you, however there are a number of software applications that make it relatively easy for you to create one yourself if you are prepared to learn how to. Similar rules apply in terms of selection and presentation of images as for your portfolio, although you may choose to include more images on a website (see page 337). Because websites are interactive and inherently non-linear, it can be useful to group your images in different galleries and therefore you have an opportunity to present much more work, although again you must make sure that they represent the best of your work. You will also have an opportunity to include a short CV and information about yourself. You may even use the site to sell images. Bear in mind the issues around copyright: include copyright statements clearly throughout and give some consideration to image security and watermarking.

SUMMARY

![]() Unless you choose to work as a photographer employed by an organization, being successful in a career in photography involves an understanding of a number of aspects of business practice, including bookkeeping, insurance, contracts, the nature of commissioning, general administrative systems and self-promotion.

Unless you choose to work as a photographer employed by an organization, being successful in a career in photography involves an understanding of a number of aspects of business practice, including bookkeeping, insurance, contracts, the nature of commissioning, general administrative systems and self-promotion.

![]() Although you may use an accountant for end of year tax returns, you will need a number of systems to keep track of the financial aspects of your business, including invoices, expenses, purchasing, petty cash and the depreciation of equipment.

Although you may use an accountant for end of year tax returns, you will need a number of systems to keep track of the financial aspects of your business, including invoices, expenses, purchasing, petty cash and the depreciation of equipment.

![]() You will need to make sure that you have insurance to cater for the needs and size of your business. At the least you should have equipment insurance and if you have anyone working for you, paid or unpaid, you will need Employer’s Liability insurance, or the equivalent. Other useful insurance includes Public Liability insurance and Professional Indemnity insurance.

You will need to make sure that you have insurance to cater for the needs and size of your business. At the least you should have equipment insurance and if you have anyone working for you, paid or unpaid, you will need Employer’s Liability insurance, or the equivalent. Other useful insurance includes Public Liability insurance and Professional Indemnity insurance.

![]() When deciding what to charge for a job, it will usually be based upon your day rate. In some cases the client may specify a day rate; otherwise your day rate should be calculated to take into account business overheads and your salary. Also included in the fee will be expenses directly associated with a particular shoot.

When deciding what to charge for a job, it will usually be based upon your day rate. In some cases the client may specify a day rate; otherwise your day rate should be calculated to take into account business overheads and your salary. Also included in the fee will be expenses directly associated with a particular shoot.

![]() You will need to track the progress of individual jobs and expenses and ensure that you have a consistent process for invoicing and chasing payment. To do this you will need a good system of paperwork, which should include the terms and conditions for an individual contract. This ensures that you cover yourself and can take legal action for non-payment.

You will need to track the progress of individual jobs and expenses and ensure that you have a consistent process for invoicing and chasing payment. To do this you will need a good system of paperwork, which should include the terms and conditions for an individual contract. This ensures that you cover yourself and can take legal action for non-payment.

![]() Your terms and conditions define the legal basis for work to be undertaken. They will be negotiable before a contract being agreed. You must ensure that both parties are clear about the terms and conditions for a particular job, as clients’ terms and conditions can override the photographer’s. All changes should be confirmed in writing.

Your terms and conditions define the legal basis for work to be undertaken. They will be negotiable before a contract being agreed. You must ensure that both parties are clear about the terms and conditions for a particular job, as clients’ terms and conditions can override the photographer’s. All changes should be confirmed in writing.

![]() A model release form should be used when photographing people, other than in certain documentary or press shots where the people are a natural part of the scene. This is particularly important when photographing minors.

A model release form should be used when photographing people, other than in certain documentary or press shots where the people are a natural part of the scene. This is particularly important when photographing minors.

![]() Copyright is important in protecting your interests and ensuring that your images are not used without your permission.

Copyright is important in protecting your interests and ensuring that your images are not used without your permission.

![]() Copyright, in most cases, automatically belongs to the photographer (unless working as a staff photographer or for some news agencies). You should avoid giving up or assigning your copyright wherever possible, as this means that you will no longer have any control over the image and cannot make money from it.

Copyright, in most cases, automatically belongs to the photographer (unless working as a staff photographer or for some news agencies). You should avoid giving up or assigning your copyright wherever possible, as this means that you will no longer have any control over the image and cannot make money from it.

![]() You may instead licence your images, which allows a client to use the images under specific conditions and for a particular duration. Clients may ask for an exclusive licence for that period. They may also negotiate further licences once one has expired.

You may instead licence your images, which allows a client to use the images under specific conditions and for a particular duration. Clients may ask for an exclusive licence for that period. They may also negotiate further licences once one has expired.

![]() Copyright is more complicated when referring to digital images. The storage of copies of digital images and the altering of digital images constitutes copyright infringement.

Copyright is more complicated when referring to digital images. The storage of copies of digital images and the altering of digital images constitutes copyright infringement.

![]() Self-promotion is vital to the success of your business. Care must be given to the way in which you present yourself, your premises and your work. A portfolio is an important opportunity to present your work and should be carefully compiled. A website is also a necessary marketing tool.

Self-promotion is vital to the success of your business. Care must be given to the way in which you present yourself, your premises and your work. A portfolio is an important opportunity to present your work and should be carefully compiled. A website is also a necessary marketing tool.