5

Preparation: Ready for Seizing Opportunity

“Spectacular achievement is always preceded by unspectacular preparation.”

~ ROBERT H. SCHULLER

Mother Teresa once said, “We can do no great things, only small things with great love.” When you take pride in perfecting the minor details of serving a client or handling an employee, big things begin to happen in a positive manner. Championship basketball coach John Wooden would invest the first few minutes of the first two weeks of practice demonstrating to every player how to properly put on his socks, shoes, and shoelaces. He wanted no slippage and no blisters taking any attention away from the important elements of the game of basketball. What things in your firm are the equivalent of teaching your staff how to put on their socks and shoes?

Leadership consists of both science and art. Proper preparation and planning is the science, and adapting to unexpected changes and seizing unexpected opportunity is the art. Some people invest so much time preparing that the project never gets launched. Others just seem to wing it. So, what is the proper balance between preparation paralysis and winging it? This chapter will give you tools to improve both the science and art of your leadership and preparation skills.

Keith Farlinger, CEO of the national firm BDO Canada LLP in Toronto, Canada, says that preparation is essential to seizing opportunities that lead to your vision.

You need to be aware of opportunities out there, but when there is an opportunity that allows you to take a quantum leap, seize it. You need to know where you’re going, what your vision is. I say to our up-and-coming leaders, “If you get a chance to do something different or to progress, make sure you seize that opportunity; don’t wait for it to come around again.”

If you’re not prepared, you’re probably better off postponing things until you get prepared rather than go in and try and wing it. I’ve had situations where I have gone in and tried to wing, it and it just doesn’t work very well.

We are all blindsided by adversity from time to time. The best leaders understand this and are seldom thrown off stride when it occurs. They prepare for the opportunities that adversity presents; namely, they know that their response can separate them and their firm from firms whose leaders get stunned and disheartened when fate frowns. Expect to encounter rough patches and use them to become stronger.

Preparation, Preparation, Preparation

Just as realtors preach location, location, location, accountants should be the biggest advocates of preparation. It’s our thoroughness and consideration of all the details that protects clients. Yet, in our own internal work, leaders do not always take time for proper preparation. As mentioned earlier, accountants are a smart bunch. They are very capable of winging it, but that won’t produce the most effective results over the long run.

They say that luck is preparation meeting opportunity. Success comes to those who are ready to sail when their ship comes in. Those who learn the value of preparation too late can’t always recover. It has been said that nobody plans to fail, but many have failed to plan. Preparation involves critical thinking, research, planning, training, and organization. Proper preparation provides a process to help you to persist through the difficulties of any initiative.

“Prepare thy work without, and make it fit for thyself in the field; and afterwards build thine house.” In Proverbs 24:27, Solomon is simply saying do first things first. A job such as arranging your office furniture must take second place for serving a client’s needs. Preparing to work in the correct order can be as simple as learning to follow the directions in a preexisting process. However, many people would like to think that the old ways don’t work. They disregard the wisdom of the past and elect to go through the school of hard knocks. Solid preparation can save years of frustration.

An effective leader develops the ability to correctly identify the key details in serving a client (such as building the relationship, managing expectations, cross-serving, and handling mistakes in a responsible manner); attacking a market; or working against a competitor to create advantages.

Just as a good accountant isn’t sloppy with financial and tax matters, a good leader isn’t careless about the details of leading a firm, especially in good times.

Bob Bunting, former CEO of megaregional firm Moss Adams LLP in Seattle, WA, argues, “Most accounting professionals would agree that true leaders do their best work in hard times. I think leaders, even the best leaders I have ever seen, are not at their best advantage in good times. I would admire somebody who could do brilliant things in wonderful times, but I am not sure I’ve seen a lot of that.”

Scott Dietzen, managing partner, Northwest Region, of the national accounting firm CliftonLarsonAllen LLP in Spokane, WA, agrees

I think it’s very difficult to lead in good times. As goofy as that sounds, leadership is tougher in good times because battling complacency is more difficult than helping people who are dealing with fear and anxiety. It’s easier to get the attention of those in fear. It’s no different than coaching a team that is playing an opponent who is much beneath them. Most teams always play down to the level of their competition, and I think organizations are very similar.

Developing Your Leadership Skills

The ability to lead is really a collection of skills, nearly all of which can be learned and improved, but leadership ability does not come overnight. Learning to lead is complex and requires preparation and learning. The most insidious danger is actually when you have developed a successful leadership style. Situations change, and different people respond best to different leadership styles. However, when you are successful with one style, you will tend to use it across all situations and people, which is less than optimum.

In a study of top leaders from a variety of fields, leadership experts Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus discovered that there is a strong link among personal growth, preparation, and leadership. “It is the capacity to develop and improve their skills that distinguishes leaders from their followers,” say Bennis and Nanus. Good leaders are learners, and the learning process is continual—a result of persistence and preparation.

As long as a person does not know what he or she doesn’t know, he or she will never grow. When you recognize areas where you can improve or adapt your leadership skills, and you begin the discipline of preparing to lead, terrific things begin to happen in your life. In this book, I’ve attempted to provide a pyramid for self and team improvement. Former British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli said, “The secret of success in life is for a man to be ready for his opportunity when it comes.” When a person prepares daily for the challenges of leadership, his or her leadership skills begin to develop. An old proverb says that champions don’t become champions in the ring—there they are merely recognized. Champions grow from intensive training before the fight. Even if you have natural talent, you will benefit from daily preparation to lead.

Laying the Groundwork by Seeking Input From Others

One important factor that leaders can forget is that it’s not your job to come up with all the answers or even decisions. Often, the people on the front lines can provide valuable input. You need to gather it before you move ahead.

When I became CEO of Advantage Companies, the firm was in a serious financial condition because its former management team had misspent much of its capital. During my first meeting with the board of directors, I had prepared a long list of priorities for their consideration. I laid the list on the table and began to expound on the necessity for raising new capital and rebuilding some of the infrastructure. At the time I was 31 years old, and the average age of the directors was about 60 years old! I was planning to bowl them over with my creativity and drive, but, I was not fully prepared.

About one hour into my presentation, one of the directors spoke up and said, “I think we should sell one of our pieces of real estate and use the equity for our capital needs. No banker in his right mind would lend us money, and no investor would put money into this operation until it gets on its feet.” The board quickly approved the idea, and I was instructed to sell the real estate in Bossier City, LA.

Although I had prepared for many hours thinking through various options, the one thing I had not done was ask the directors for their input. From that day forward, when I was preparing for a board meeting, I consulted several directors before the meeting, and they previewed my plans. That system worked much better. Together, we turned the company around and began to make profits.

Even when you actually know all the right answers, a smart leader seeks input from others. It will provide buy-in and more enthusiastic participation from those you consult, if nothing else.

Preparing to Lead Strategic Initiatives

The accounting and finance world is in constant motion. Our firms and people are challenged daily with conditions that change at the speed of light. To succeed in this rough business environment, firms frequently undertake strategic initiatives. Examples of such initiatives could include the acquisition of another accounting firm, the implementation of a new business model, the change of the firm’s reporting structure, adopting a new practice management system, or going paperless.

Too often, there is little preparation for the introduction and implementation of major new initiatives. Missteps in preparing, planning, and executing initiatives waste time, money, and other resources. At times, the chaos resulting from poorly prepared and implemented initiatives lessens employees’ respect for their owners and leaders. When major initiatives fail or fade, accountants become cynical and more resistant to the next big initiative.

A number of preparation processes are available. I want to propose a preparation process that clearly lays out the steps to achieve a prepared team and that will help you accomplish your vision and carry out your firm’s mission.

Accomplishing the firm’s initiatives requires the leaders to set a clear direction from the beginning. The leader’s role is to create an environment that prepares and supports those who must carry out the many details that will determine the success of the endeavor. You must create and communicate a vision, set a strategy, and identify the right people to execute the strategy to achieve your goals. Leaders must ensure that those executing the strategy have enough time, money, and resources. In our consulting practice, we have developed and tested a process and set of tools to assist leaders in planning and preparing to implement various firm initiatives.

These eight preparation tools have been tested to help you prepare to lead any initiative or team. Although these tools are guides, they do not need to be implemented in the exact order given:

1. Prepare a vision for the initiative by creating a high-resolution picture of the future.

2. Clarify each person’s role on the team-driving the initiative.

3. Assess the opportunities that the initiative will bring to the firm.

4. Understand the threats that are likely to impede success.

5. Outline any research for fact-finding that must be accomplished before launching.

6. Budget the resources that will be needed to carry out the initiative.

7. Develop the project game plan.

8. Launch the initiative with overwhelming power.

Step 1—Prepare a High-Resolution Picture of the End Game

Even under the best circumstances, a firm’s initiatives still have the potential for going haywire. Busy season, competing priorities, and time and money constraints frequently sidetrack initiatives before the vision is achieved. A shared vision is the catalyst that will prepare your team to overcome these constraints and barriers. A leader’s first challenge is to create and communicate a high-resolution picture: a vision for the undertaking that aligns with the vision for the firm. In chapter 11, “Vision: Reality in the Future,” vision is discussed in depth, but here is a quick example of a high-resolution picture of the end game:

Too often, what is missing is a strong sense of purpose and direction to guide staff members through the rough patches. First, gather any of the firm’s vision documents and prepare them for review by the leadership team. You may not have to recreate the vision for the firm if you already have a clear picture of the future. If you find more than one document that is pertinent, you might want to consolidate or summarize them.

For example, most good vision documents answer the following:

▴ What is the owner’s vision of the initiative or the firm in one, three, or five years?

▴ How would the firm treat people, clients, employees, families, and the community?

▴ How would you like the firm to be characterized by outsiders and insiders?

▴ What is the end state of this project, and how does it fit the firm’s vision?

▴ What are the values that the firm stands for?

▴ State what makes the initiative worth doing. For example, “Our costs aren’t competitive, and we are losing market share.”

▴ State the possible consequences to the firm of not succeeding with this initiative. For example, “Our level of client service may decline, and we won’t be able to compete.”

▴ Complete a step-by-step action plan for moving from the present state to the end state.

▴ What approach will you use?

▴ Set assignments of tasks and deadlines for their accomplishment.

Then, you can create the initiative vision by stating the specific reason why the firm is introducing this particular endeavor. How does it support the overall vision of the firm? For example, “A major goal of our firm right now is to reduce our costs. To do so, we must become more efficient in the delivery of our products and services.”

Include a description of the current state and a picture of the desired future state. Also, describe what it will take to close the gap between the current state and the desired future state. For example, “Our current culture supports complacency. Our future culture must focus on continuous improvement and constantly raise the bar for performance expectations. To get there, we will need to clarify performance goals for each department and person, develop systems that reward continuous improvement, and provide leadership to guide the culture change.”

Step 2—Clarify Each Staff Member’s Role

Do not confuse your individual roles and goals with the overall goals of the initiative. You must specify each person’s responsibilities, goals, and actions. People on the leadership team may have activities that impede the group’s goals. For example, you may have a leader assigned to a role to refine and challenge everyone else’s ideas, action steps, and purpose. Or suppose that the mission of your firm’s initiative is to implement a new tax-processing system. Your role as leader could be to set the budget, the general direction, and time lines for the project. You may have another leader oversee the entire design phase. Another person could lead the implementation of the new tax process. If the leadership team chooses to oversee and direct project management, the duties will be much more extensive than if the team chooses to set direction only.

If you adopt the role of setting direction only, then you must appoint a project leader or manager to carry out the more intensive management of the initiative. Each person on the leadership team must have a clear understanding of his or her role in the process of executing the initiative. The team should discuss the behaviors that will be consistent with its roles. Leaders are natural advocates for the team’s or firm’s initiative, so your words and actions will be watched by everyone to see if they have integrity. It is easy for misguided leaders to undermine their own projects by missing meetings, making cynical comments, and not carrying out the proper role. It is crucial that all people on the leadership team discuss and commit to integrated words and actions, so that followers are not misled or confused.

Step 3—Assessing Potential Opportunities

You must quantify the potential payoffs that are expected from the initiative. Projecting the benefits will give your team motivation to move forward and overcome the obstacles that will pop up from time to time.

To complete this step

▴ clarify the expected outcomes of the initiative in financial and other meaningful terms.

▴ list any factors working for you, such as a good economy, loyal clients, industry expertise, a trusted reputation, or a skilled group of professionals.

▴ critically think through ways to capitalize on these factors, such as having several important clients endorse the initiative as being very important to them.

Step 4—Understanding Possible Threats

Although opportunities give us hope and motivation, we must also assess the external threats to the firm’s initiative. List any external factors that may slow you down or cause you to fail. Things like a workforce that is adverse to change, software that has not been fully beta tested, or team members who haven’t experienced this process before are threats to consider.

Gordon Krater, managing partner of megaregional firm Plante & Moran, PLLC, in Southfield, MI, was taught early to assess the threats.

My first day at Plante Moran, Frank Moran taught me my first leadership lesson. I was 22, and he was 62. He came by, and he said, “Hey, do you play racquetball?”

And I said, “Well, yes I do.”

He said, “Do you have your stuff in the car?”

I responded, “Well, yes I do.”

He said “Let’s go play at lunch.”

I said, “That would be great,” thinking to myself, this should be an easy match; I’m a pretty good athlete.

We went to play, and he says, “I’m going to spot you 15 points, and we are going to play to 21.”

He didn’t even break a sweat, and I was running all over the court, and he hardly moved. I was pretty confident, and Frank proceeds to beat me 21 to 18. I found out later he was state squash champion. Later, he asked me, “So, what did you learn?”

And I said, “You mean about racquetball? Because I learned a lot about where to put the ball, so you don’t have to move.”

He says, “You learned not to underestimate people.”

And I said, “I sure did,” and I thought what a wonderful lesson right out of the gate.

Step 5—Gather and Review Relevant Research

Before initiating a project or setting a budget and action plan in place, leaders must gather as many facts as possible. Consider questions like these:

▴ Has another firm attempted this in the past?

▴ What experience do the partners, leaders, and managers have in this particular type of endeavor?

▴ What are our clients’ attitudes on this?

▴ Do we have confidence in any outside consultant we may be using?

▴ What are the legal and ethical implications?

▴ Have others failed or succeeded?

▴ What does the trend in the economy tell us?

▴ Are we leading the competition, or are we following them?

Step 6—Budgeting Time, People, and Money

One of the many issues that I’ve found in strategic plans is that many firms lay out plans but fail to allocate budgets. A plan without a budget allocation is a nonplan. Usually, it says that everyone hasn’t agreed to the plan, perhaps the managing partner who is holding the purse strings. This will cause enormous confusion and nonaction toward the initiative. You have made decisions that will set the stage for the initiative. Now, using the following key steps, work through the issues that will allow you to develop a budget for carrying out the project:

▴ Describe the initiative deliverables.

▴ Identify a person or team with responsibility for each deliverable.

▴ Describe the leader’s roles pertaining to each deliverable. For example, perhaps one of the deliverables is training on a new service. It is the leader’s responsibility to see that someone on the team will develop an in-depth training module for the launch of the new service.

▴ Estimate costs, both in people hours and dollars for this initiative.

▴ Estimate the return on your investment from the resources that you commit to the project.

Step 7—Develop the Initiative Game Plan

Because change-initiative projects tend to be complex, a detailed project game plan is essential for each initiative in the game plan. You use the big-picture game plans to record tasks, time lines, responsible people, and costs. Game plans make everyone aware of the deadlines, reduce uncertainty, and communicate steps in a logical order. You may need to adjust your game plans later based on responses from critical stakeholders, reports from your teams, and other factors.

Nevertheless, the leadership team should establish a preliminary game plan to guide the firm in its overall approach. Here are some steps that you could use to prepare this game plan:

▴ List the strategic objectives that will be accomplished in each period of the plan.

▴ List the main initiatives necessary to accomplish each objective.

▴ Give your best estimate of completion dates for each initiative.

▴ Define a measurement for each initiative, so you can determine the level of success.

▴ Designate who owns the responsibility for each deliverable.

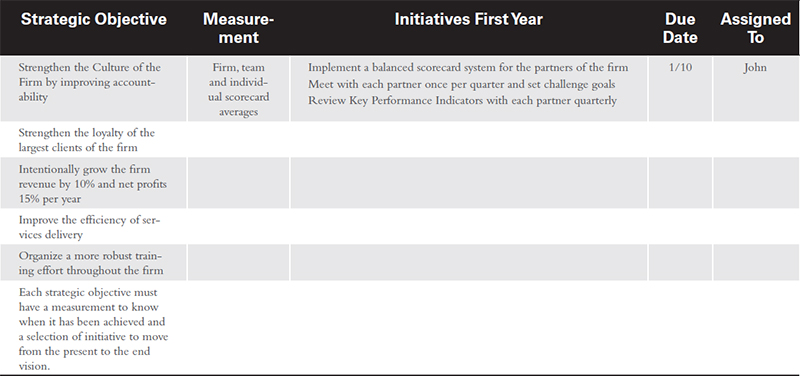

A sample of a big picture, firmwide, or initiative game plan is provided in exhibit 5-1 found at the end of this chapter.

Step 8—Launch the Initiative With Overwhelming Power

If you’ve ever watched the space shuttle blast off toward outer space, you have witnessed the power necessary to launch any new initiative. Over 95 percent of the total power necessary to launch a space shuttle and return it safely to the earth is expended in the first 5 minutes of its blast off. Once the space shuttle has pierced the atmosphere and broken free of gravitational pull, the next 2 weeks of its mission use only 5 percent of its total power. This is how you must think about launching a new initiative.

Bob Bunting launched an initiative with the power from the top, hoping to increase his firm’s expertise in certain areas.

We have some people we’ve brought in, and they comfortably engage other people in their work because they were raised in big firms where you don’t hoard the work. They so easily leverage themselves. As we looked at our specialty areas where we wanted to be breakout leaders professionally—in banking and telecommunications—in some places, our growth required us to go out and get additional help; in other cases, we weren’t really getting off the ground, and so we didn’t have the right kind of leadership.

Bob asked his industry group leaders to name their competitors, and he identified 45 people who were “eating Moss Adams’s lunch,” so to speak. He called each one of the 45 personally.

I told them the truth. I said, “We are looking at you because you are a very effective competitor. We want to dominate our market space. We think that you can help us do that. We think that what we do is very important, and we may even think it’s more important than your firm does; I don’t know the answer to that question, but if you think that’s a possibility, maybe you’d have lunch with me.” Well, out of 45 people, no one turned me down for lunch!

But it was because the CEO called, and it was because they thought they were pretty good. But if they had a peer from Moss Adams calling them up, that doesn’t quite get them the level of recognition that they think they’ve earned. And I have to agree that they’ve earned it because they are eating our lunch in the marketplace. We hired 23 people over a 30-month period as a result of that effort.

Preparation Is for Action

All advanced manager training courses will tell you that if you want to get something done, give it to a busy person. Busy people have momentum, and they have no time to make excuses. Conversely, the professional student is a common phenomenon on college campuses. This is the student who is always learning but never graduating or getting a job. The same is true with many accounting firm teams: they love to spend time planning, but they’re not as good at the real work of implementation.

Rick Anderson, CEO of megaregional firm Moss Adams LLP in Seattle, WA, shares

Within the practice of accounting, there are people who believe you can take your time and evaluate, evaluate, evaluate, and never decide or act. Leadership is not like that. Leadership requires you to be prepared to make decisions quickly, in the moment. For instance, client service is only good when it’s delivered on time and right, and sometimes, you don’t have a lot of time. There are times when people are too deliberative, even within the practice of public accounting.

Your leadership team is responsible for the success or failure of your firm’s initiatives. You must prepare carefully from the beginning, and you must prepare a game plan that will allow others to accomplish the initiative goals and realize successful outcomes. The more carefully you prepare up front, the easier it will be to achieve your objectives. Most firms’ initiatives are expensive in both dollars and time. If it is worth it to invest these precious resources in the initiatives, it is certainly worth it to invest the time to prepare. Failure is the reward for those who disregard the need to be prepared.

Getting Started

Depending upon your personal leadership ability, once you get underway, you will start to attract a following to your cause. Do not look for others with their own missions to jump on your bandwagon. You need to first find your own following, or rather, your own following will find you. As your leadership ability grows, you may “lead a pack” if you are able to attract other leaders to your mission. Remember that servant leadership is based upon a how many can I help mentality, rather than trying to acquire as many followers as possible.

As you work to prepare your own leadership and a committed group of followers, keep the following ideas in mind:

1. Small groups can prepare more efficiently. Smaller teams improve creativity, accountability, a sense of ownership, and execution.

2. Utilize staff members at appropriate levels of your firm to prepare their sections of any initiative. Although current leaders are typically selected to oversee major strategic objectives and initiatives, it may be helpful to assign up-and-coming leaders to smaller roles to test them and give them experience.

3. You learn a great deal about potential future leaders by how they think and act. The best leaders think about others and their mission more than they think about themselves.

4. You will begin to get more clarity on your life mission as you become prepared to lead. Leadership preparation is not learned solely in the classroom, just as you cannot learn to play golf simply by reading a book or watching a video. At some point, you need to get a club in your hands and play the game.

Conclusion

One of the greatest leaders of the United States was Theodore Roosevelt. He was also physically one of the toughest men ever to hold the office of president. He was a cowboy, a cavalry officer, an explorer, and a big-game hunter. He held regular boxing matches at the White House. After he left office, he was shot on his way to give a speech. With a bullet in his chest, he insisted on giving his hour-long speech before he allowed the doctors to attend to him.

But Roosevelt was not always so vigorous. As a child, he was physically weak, with horrible asthma and poor eyesight. His father told him, “You have the mind, but you have not the body, and without the help of the body, the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make the body.” Roosevelt began spending time every single day building his body for the rest of his life.

When he died, a book was removed from underneath his pillow. Even near death, he was preparing himself for a new challenge. That’s the way it is with leadership; everyone has the potential to be a great leader if they will apply themselves daily to the challenge.

When you are well prepared, you instill confidence in your team members, and their trust in you grows. Poor preparation has the opposite effect.

Exhibit 5-1: Sample Firm Game Plan

Vision

10-10-50: 10 offices, 10 Years, $50 Million in Revenue

Rank in the top 100 accounting firms to work for in the United States in Accounting Today magazine.

Mission

We at Smith and Jones commit our resources, our intelligence and our strengths to helping clients make wise and long-lasting financial decisions.

Core Values

We commit to integrity above all else, so that our actions match our promises.

We commit to five-star client service that focuses on heart, mind, and a sense of urgency in the pursuit of results for you.

We commit to results by providing customized real value to our clients.

Strategic Objectives

1. Strengthen the culture of the firm by improving accountability.

2. Strengthen the loyalty of the largest clients of the firm.

3. Intentionally grow the firm revenue by 10 percent and net profits by 15 percent per year.

4. Improve the efficiency of services delivery.

5. Organize a more robust training effort throughout the firm.

6. Improve the compensation system of the firm, so that people have incentive to help the firm achieve its goals.

7. Focus on leadership development at all levels of the firm.