A Model of Managing

A good theory is one that holds together long enough to get you to a better theory.

Donald O. Hebb (1969)

In search of a better theory, we turn now from the characteristics of managing to its content: what is it that managers actually do, and how?

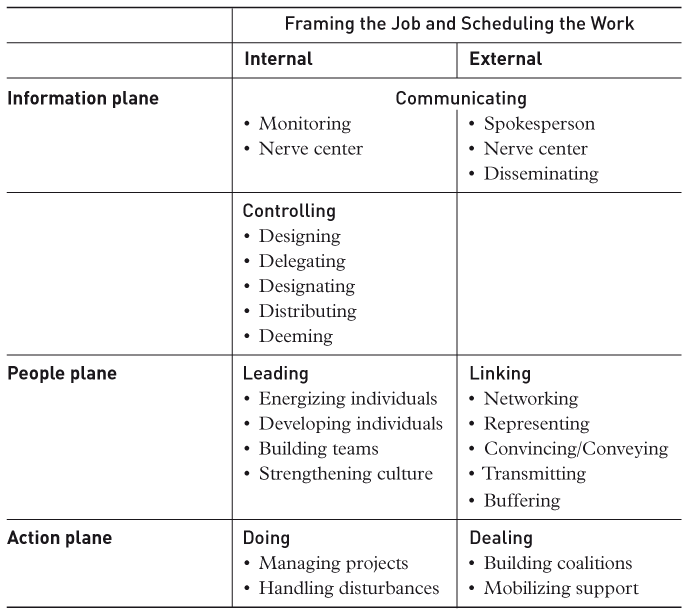

We begin with the gurus, most of whom have seen the job in its component parts, not its integrated whole, and the academics, who have seen the whole as lists of disconnected parts. This chapter proposes a model of managing that positions the parts within the whole, by depicting managing as taking place on three planes: information, people, and action, inside the unit and beyond it. A final section describes the “well-rounded” job of managing as a dynamic balance.

Managing One Role at a Time If you wish to become famous in management—one of those “gurus”—focus on one aspect of managing to the exclusion of all the others. Henri Fayol saw managing as controlling, while Tom Peters has seen it as doing: “‘Don’t think, do’ is the phrase I favor’” (1990; on Wall Street, of course, managers “do deals”). Michael Porter has instead equated managing with thinking, specifically analyzing: “I favor a set of analytical techniques for developing strategy,” he wrote in The Economist (1987:21). Others such as Warren Bennis have built their reputations among managers by describing their work as leading, while Herbert Simon built his among academics by describing it as decision making. (The Harvard Business Review concurred, for years pronouncing on its cover, “The magazine of decision makers.”)1

Each of them is wrong because all of them are right: Managing is not one of these things but all of them: it is controlling and doing and dealing and thinking and leading and deciding and more, not added up but blended together. Take away any one of these roles, and you do not have the full job of managing. In that sense, by focusing on one aspect of the job to the exclusion of the others, each of these gurus has narrowed our perception of managing rather than broadening it.

An Abundance of Lists Go beyond the gurus, to some of the less popular fare of the academics, and you find acknowledgment of this problem: they offer lists of managerial roles. The good news is that these are more comprehensive; the bad news is that they take the job apart without putting it back together. It feels like Humpty Dumpty, lying in broken pieces on the ground.

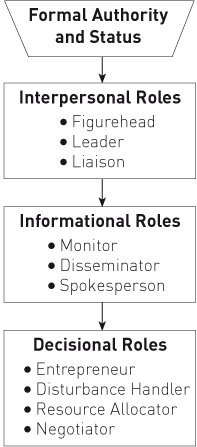

I was responsible for one of these lists. One chapter of my 1973 book, called “The Manager’s Working Roles,” presented what I thought was a model, which I later came to realize was just another list, albeit with arrows, as shown in Figure 3.1.2 So while managers may have related well to my description of the characteristics of managing, they did not take particularly well to my list, or those of others (even if some academics did). As one manager commented: “the descriptions are lifeless and my job isn’t” (in Wrapp 1967:92).

Thus, in 1990, I decided to revisit the content of managing. Since the publication of my 1973 book, I had been collecting new articles on the subject, which by then filled two boxes. I opened them and also looked at the books on the subject—about forty in all, from Barnard (1938) to Zaleznik (1989). I wanted to know what we formally knew about the content of managing.

Figure 3.1 THE MANAGER’S WORKING ROLES (from Mintzberg, 1973:59)

The answer: on one hand, quite a bit; on the other, not much at all. All of this material together seemed to cover the things that managers do (Hales 2001:50), but it did not amount to much of a theory, or a model, to help managers understand their work.3

What’s the Problem?

How can this be so? We live in societies obsessed with management and especially leadership, now more than ever. We idolize “leaders”; we fill bookstores with biographies of them, under “Fiction” as well as “Business” (sometimes being unable to tell the difference); we pretend to train huge numbers of students to become them; we have even created a special class for them in airplanes (and beyond). Yet we cannot come to grip with the simple reality of what they do. Why?

Let me consider two possible explanations. The first is that, as in other primitive societies, we live in mortal fear of our own gods, or at least our own myths, and management/leadership is surely one of them. Perhaps we fear the consequences of revealing their nakedness, or our own. Of course, we write about “leadership,” ad nauseum, but little of that touches on the everyday realities of managing.

Carlson offered another explanation in his early study: that “executive behavior” is “so varied and so hard to grasp” because “it is more a practical art than an applied science” (1951:109–110). How to theorize about that?

Whitley took this further, arguing that managerial tasks are specific to context, and thus dependent on knowledge of the particular organization and its problems, which are constantly changing (1989:213, 215). How, then, can we develop general theory about what managers do, instead of specific descriptions of what particular managers did?

I beg to differ. At some level of abstraction, we can generalize. Let me illustrate. To become a senior manager (“partner”) in a consulting firm means to become responsible for selling, which is the work of specialists in most other businesses. Yet do we want to describe managerial work as selling? As Peter Drucker put it:

Every manager does many things that are not managing…. A sales manager … placates an important customer. A foreman repairs a tool…. A company president … negotiates a big contract…. All these things pertain to a particular function. All are necessary, and have to be done well. But they are apart from that work which every manager does whatever his function or activity, whatever his rank and position, work which is common to all managers and peculiar to them. (1954:343)

Before we throw out the managerial baby with the selling bathwater, let’s ask ourselves why senior managers of consulting firms do this selling. The obvious answer is that many consulting services have to be sold at senior levels in the buying company, and so they require the intervention of senior managers in the selling company. On one hand, therefore, the task is specialized and context-specific; on the other hand, it has to be done by managers and so is intrinsically managerial (see also Hales and Mustapha 2000:22).

Indeed, a good deal of what we generally accept as intrinsically managerial corresponds to specialized functions in the organization: managers brief subordinates, but their organizations have formal information systems; managers serve as figureheads at ceremonial events despite the presence of public relations specialists; managers have long been described as planners and controllers, while near them can be found planning departments and controllership offices. A good part of the work of managing involves doing what specialists do, but in particular ways that make use of the manager’s special contacts, status, and information.

So let’s get past our myths and our deities, and get on with understanding managing as it is practiced.

TOWARD A GENERAL MODEL

When I opened those boxes and looked at those books, my intention was not to find out what managers do—we knew that already—but to weave that into a comprehensive model. Hence, I did not set out to do more research, not yet (the twenty-nine days of observation mostly came later), but simply to draw together the results of existing descriptions and research. My focus was really quite simple: to get it all on one sheet of paper, in the form of a single diagram. This was not meant to trivialize the job or to suggest that all its nuanced complexity could be described on one page, only to offer the reader a place where the whole of managing could be seen all at once—comprehensively, coherently, interactively—even if that page required many more of explanation.

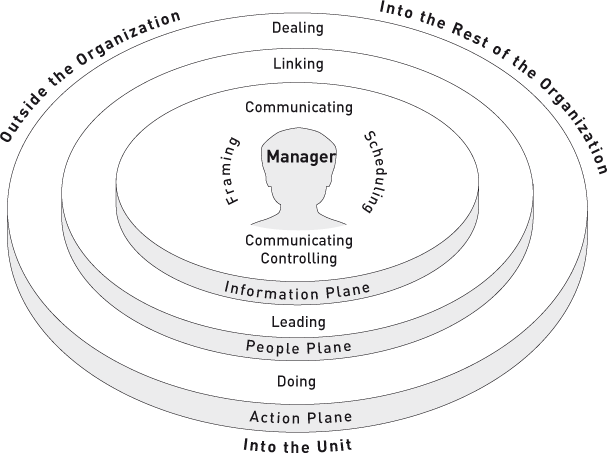

After perhaps a dozen efforts over many years, I developed that one page to my satisfaction, as reproduced in Figure 3.2.4 The first time I showed it to a manager—a friend, over dinner—he immediately pointed to where were the strengths and the weaknesses of the managers in his company. That was exactly the response I wanted.5

The figure has come out looking a bit like an egg, perhaps in honor of Humpty Dumpty. In the spirit of the opening quotation of this chapter, my earlier effort had held together long enough to get me to this model, which I hope will hold together long enough to help others get to better models.

Figure 3.2 A MODEL OF MANAGING

An Overview of the Model

Figure 3.2 puts the manager in the center, between the unit for which he or she has formal responsibility (by definition) and its surroundings, of two kinds: the rest of the organization (unless the manager is chief executive, responsible for the entire organization), and the outside world relevant to the unit (customers, partners, etc.).

The overriding purpose of managing is to ensure that the unit serves its basic purpose, whether that be to sell products in a retail chain or care for the elderly in a nursing home. This, of course, requires the taking of effective actions. Mostly other people in the unit do that, each a specialist in his or her own right. But sometimes a manager gets close to this action, as when Jacques Benz, Director-General of GSI, joined the meeting of a project team that was developing a new system for a customer.

More commonly, however, the manager takes one or two steps back from the action. One step back, he or she encourages other people to take action—the manager gets things done through other people by coaching, motivating, building teams, strengthening culture, and so forth. Two steps back, the manager gets things done by using information to drive other people to take action. He or she imposes a target on a sales team, or carries a comment from a government official to a staff specialist. So as shown in the figure, managing takes place on three planes, from the conceptual to the concrete: with information, through people, and to action directly.6

- On the day of observation, Carol Haslam of Hawskhead could be seen working on all three planes. On the action plane, she was deeply involved with developing projects for new films—she was doing deals galore. On the people plane, she was maintaining her vast network of contacts used to promote these projects, as well as building teams of filmmakers to execute them. And on the information plane, all day long she was collecting and disseminating ideas, data, advice, and other information.

Two roles are shown as being performed on each plane. On the information plane, managers communicate (all around) and control (inside). On the people plane, they lead (inside) and link (to the outside). And on the action plane, they do (inside) and deal (outside). Also shown, within their own heads, managers frame (conceive strategies, establish priorities, etc.) and schedule (their own time). Each aspect of the model is discussed in turn before all of them are discussed together in conclusion.

THE PERSON IN THE JOB

Positioned at the center of the model is the manager, who personally carries out two roles in particular: framing and scheduling.

Framing the Job

Framing defines how a manager approaches his or her particular job. Managers frame their work by making particular decisions, focusing on particular issues, developing particular strategies, and so forth, to establish the context for everyone else working in the unit.7 Alain Noël (1989) has called these the managers’ preoccupations, as compared with their occupations (what they actually do)—which can sometimes amount to a single “magnificent obsession.”

- Brian Adams, Program Manager for the Global Express aircraft at Bombardier, had a magnificent obsession, imposed by the senior management: to “get it in the air” by June. “Then, we’ll see,” he commented. In contrast, John Cleghorn of the Royal Bank of Canada had a variety of preoccupations as its chairman, concerning the improvement and success of the company. (Both their days are described in the appendix.)

One of the new managers studied by Linda Hill quickly found out about the importance of framing: “I expected to come out of the starting gate with the knowledge … now I find I’m out here inventing the wheel” (2003:51). We return to framing in our discussion of managerial styles in Chapter 4 and strategy formation in Chapter 5.

Scheduling the Work

Scheduling is of great concern to all managers: the agenda inevitably gets a lot of attention. A half century ago, Sune Carlson noted how managers “become slaves to their appointment diaries—they get a kind of ‘diary complex’” (1951:71). Scheduling is important because it brings the frame to life, determines much of what the manager seeks to do, and enables him or her to use whatever degrees of freedom are available (Stewart 1979).

Needless to say, scheduling was evident in all twenty-nine days of observation. It has to be done in all managerial jobs, but as a means to other ends—namely, the performance of the other roles. Thus, the diaries were often out, and much juggling of schedules took place.8

The manager’s schedule can have enormous influence over everyone else in the unit: whatever gets in the agenda is taken as a signal of what matters in the unit. In fact, when managers schedule, they are often allocating not only their own time but also that of the people who report to them.9

Scheduling amounts to what Peters and Waterman (1982) have called “chunking”—slicing up managerial concerns into distinct tasks, to be carried out in specific slots of time. The problem, of course (which we shall discuss under the Labyrinth of Decomposition in Chapter 5), is how to put back together that which has been taken apart. And this is where the frame comes in: if clear enough, it can function as a magnet to draw the distinct chunks into a coherent whole. As Whitley put it, managing is “not so much focused on ‘solving’ discreet, well bounded individual problems as in dealing with a continuing series of internally related and fluid tasks” (1989:216).

Despite the attention that has long been given to decision making, managerial agendas seem to be built around ongoing issues more than specific decisions—in the words of Farson (1996:43), “predicaments” more than “problems” (see also Pondy and Huff 1985). Just look at the agendas of a typical management meeting, or else ask a manager what is on his or her “plate.”10

MANAGING THROUGH INFORMATION

We turn now to the three planes on which managing is manifested, beginning with that of information. To manage through information means to sit two steps removed from the ultimate purpose of managing: information is processed by the manager to encourage other people to take the necessary actions. In other words, on this plane the manager focuses neither on people nor on actions directly, but on information as an indirect way to make things happen.

Ironically, while this was the classic view of managing, which dominated perceptions of its practice for most of the last century, it has again become prevalent, thanks to current obsessions with the “bottom line” and “shareholder value”: both encourage a detached, essentially information-driven practice of managing.

Two main roles describe managing on the information plane, one labeled communicating, to promote the flow of information all around the manager, and the other labeled controlling, to use information to drive behavior mainly within the managed unit.

Communicating All Around

Watch any manager and one thing readily becomes apparent: the amount of time that is spent simply communicating—namely, collecting and disseminating information for its own sake, without necessarily processing it. Barnard, himself a chief executive (of New Jersey Telephone), identified the “first executive function” as “to develop and maintain a system of communication” (1938:226).

In my 1973 study, I estimated that the five chief executives spent about 40 percent of their time simply communicating in one way or another. In his study of Swedish corporate chief executives, Tengblad (2000) put 23 percent of their time at “getting information”—“the single most frequently recorded activity”—plus another 16 percent “informing and advising” (p. 15).

I did not tabulate the time spent on various activities by the twenty-nine managers of my later study, but communicating was no less evident: Norm Inkster, head of the RCMP, going over press clippings of the past twenty-four hours; someone dropping in on RCMP Division Commander Burchill “to tell you what’s going on”; John Cleghorn briefing institutional investors on happenings at the bank; Stephen Omollo in the refugee camp inspecting the reconstruction of a fence that had been blown over in a recent storm; and much more.

The communicating role exists in the model as a kind of membrane all around the manager, through which all managerial activity passes. “Communicating is not simply what managers spend a great deal of time doing but the medium through which managerial work is constituted” (Hales 1986:101). Managers take in information through what Sayles (1964) has called monitoring activities, which enable them to be the nerve centers of their units, and they send their information out through what can be called disseminating activities inside the unit and spokesperson activities outside it.

Monitoring As monitors, managers reach out for every scrap of useful information they can get—about internal operations and external events, trends and analyses, everything imaginable. They are also bombarded with such information, significantly as a consequence of the networks they build up for themselves. Thus, Morris et al. wrote about high school principals spending “a good deal of time ‘on the go’”: touring the halls, visiting the cafeteria, quick checks in the classrooms and libraries, etc.—a “constant bobbing” in and out, in order to “gauge the school climate” and “anticipate and quell potential trouble” (1981:74).11

Nerve Center Everyone reporting to a manager is a specialist, relatively speaking, charged with some particular aspect of the unit’s work. The manager, in contrast, is the relative generalist among them, overseeing it all. He or she may not know as much about any particular specialty as the person charged with it, but usually more than any of them about the whole set of specialties together. And so the manager develops the broadest base of information within the unit. As a consequence of the monitoring activities, the manager becomes the nerve center of the unit—its best-informed member, at least if he or she is doing the job well (Barnard 1938:218).

This can apply to the president of the United States compared with the cabinet secretaries and the CEO of a company compared with the vice presidents no less than to a first-line manager compared with the workers. As Morris et al. put it about those school principals: “Inside the building, the principal is the key exchange point, the information switchboard through which all important messages pass” (1982:690).

- At a lunchtime briefing of investors of the Royal Bank, John Cleghorn drew on anecdotes from his morning in the branches. The rest of the day likewise saw a great deal of communicating in and out. Mostly John was learning, picking up all sorts of scraps of detail, and in some cases more aggregated figures. But he also spent time telling people about broader issues of the bank—a pending acquisition, for example—and imbibing a sense of its values. (The full day is described in the Appendix.)

The same holds true for external information. By virtue of his or her status, the manager has access to outside managers who are themselves nerve centers of their own units. The president of the United States can call the prime minister of Great Britain, much as one factory foreman can call another factory foreman. Consider the following descriptions, the first about leaders of street gangs in America, the second about a president of the United States of America:

Since interaction flowed toward [the leaders], they were better informed about the problems and desires of group members than were any of the followers and therefore better able to decide on an appropriate course of action. Since they were in close touch with other gang leaders, they were also better informed than their followers about conditions in [the town] at large. (Homans 1950:187).

The essence of Roosevelt’s technique for information-gathering was competition. “He would call you in,” one of his aides once told me, “and he’d ask you to get the story on some complicated business, and you’d come back after a couple of days of hard labor and present the juicy morsel you’d uncovered under a stone somewhere, and then you’d find out he knew all about it, along with something else you didn’t know. Where he got his information from he wouldn’t mention, usually, but after he had done this to you once or twice you got damn careful about your information.” (Neustadt 1960:157)

Disseminating What do managers do with their extensive and privileged information? A great deal, as we shall see in the other roles. But still on this one, they simply disseminate much of it to other people in their unit: they share it. Like bees, managers cross-pollinate. As Commanding Officer Allen Burchill of the RCMP reported on his way to a management meeting with his reports: “I’m informed. But this is a go-around to make sure they’re informed.”

Spokesperson The manager also passes information externally, from people in the unit to outsiders, or from one outsider to another—for example, between customers, suppliers, and government officials. More formally, as spokesperson for the unit, the manager represents it to the outside world, speaking to various publics on its behalf, lobbying for its causes, representing its expertise in public forums, and keeping outside stakeholders up-to-date on its progress.

- Charlie Zinkan, as Superintendent of the Banff National Park, met with the owner of a campground concerned about Indian land claims. Patiently Charlie described the government’s position. The man was grateful: finally someone had explained the situation to him. At N’gara, Stephen Omollo of the Red Cross met the representative of a major donor organization who was there to audit the use of its money in the refugee camps. Stephen’s knowledge of the operations, illustrated in his detailed replies to many of the questions, was impressive—informed, articulate, and straightforward.

The Verbal, the Visual, and the Visceral It should be evident from our discussion of Chapter 2 that the manager’s advantage lies not in documented information, which can be made available to anyone, but in the current, not (yet) documented information transmitted largely by word of mouth—for example, the gossip, hearsay, and opinion discussed in that chapter. Indeed, much of an informed manager’s information is not even verbal so much as visual and visceral—in other words, seen and felt more than heard, representing the art and craft of managing more than its science. Effective managers pick up tone of voice, facial expression, body language, mood, atmosphere.

- I observed this especially in the day I spent with Stephen Omollo as he walked through the refugee camps, using every means possible to sense what was going on. Stephen greeted everyone he passed, smiling and laughing—in front of their homes, on the streets, in the markets and the fields. No few came up to shake his hand and chat. “My job is to assist and train the local staff,” Stephen said, “but there is a need to tour on foot. You need to laugh with the people.”

To conclude this discussion of the role of communicating, the job of managing is significantly one of information processing, especially through a great deal of listening, seeing, and feeling, as well as a good deal of talking. But that can damn a manager to a job of overwork or one of frustration. On one side of the managerial coin, there is the temptation to get in there and find out personally what is going on—to “avoid the sterility so often found in those who isolate themselves from operations” (Wrapp 1967:92). The danger, of course, is that this can encourage micromanaging: meddling in the work of others. But on the other side of that coin is “macroleading”: simply not knowing what is going on. We shall return to this under our conundrums of Chapter 5.

Controlling Inside the Unit

One direct use of the managers’ information is to “control”—that is, to direct the behavior of their “subordinates.” As noted earlier, for the better part of the last century, managing was considered almost synonymous with controlling. This view began with Henri Fayol’s book of 1916, based on his experience of managing French mines in the previous century, but it really flourished in the conventional manufacturing of products, such as automobiles, and then in government, as expressed in Gulick and Urwick’s (1937) popular acronym POSDCORB: planning, organizing, staffing, directing, coordinating, reporting, and budgeting. Four of these words are clearly about controlling, while the other three—staffing, coordinating, and reporting—reflect important aspects of controlling. Hence, this long-dominant description of managerial work has not so much been wrong as narrow, focusing on one restricted aspect of the job: control of the unit through the exercise of formal authority.

Controlling may have lost its preeminent status after 1960, as the people plane of managing rose to prominence. But thanks to the recent surge in “bottom line” and “shareholder value” thinking, controlling is back—with a vengeance.

I chose to leave controlling out of the ten roles of managing I described in my earlier book (although I did include one labeled “resource allocator”—an aspect of controlling). Perhaps this was my overreaction to the excessive attention it had received earlier. In any event, I include it here, but in a tangible way: in terms of how managers exercise control.

- In the refugee camps of N’gara, controlling was front and center, simply because so much that happened had to be kept under tight wraps for fear of a small incident blowing into a major crisis. “You just need to put your ear to the ground, Stephen, and find out more about what the feelings are among the refugees,” Abbas Gullet told Stephen Omollo at a meeting in the Red Cross compound. On top of this were the many Red Cross systems, procedures, rules, and regulations. In contrast, the day with orchestra conductor Bramwell Tovey exhibited much less overt controlling. He hardly “directed” this day, in the sense of giving orders, delegating tasks, or authorizing decisions. Controlling, like the other roles of managing, does vary in importance.

Administration, in some ways seen as synonymous with controlling, has for some time been put down in managerial work, as routine, boring, “bureaucratic.” Indeed, in the 1950s, Peter Drucker (1954) distinguished “managers” from “administrators” much as leaders are now distinguished from managers. Instead of rushing to glorify leadership, however—“cast[ing] off the dowdy feathers of administration for the rich plumage of leadership” (Hales 2001:53)—and thus reducing management to administration, we should be recognizing controlling as an inevitable component of all effective management and leadership.

Linda Hill found that the new managers she studied had negative connotations of “administration,” which they nevertheless reluctantly accepted as part of their job (2003:22).12 Presumably this is because, first, if the manager of the unit does not take responsibility for getting it organized and instituting the necessary controls, who will; and second, because the manager is the person in the unit held accountable for its performance. The trick is not to avoid the controlling role but to avoid being captured by it—which is true for all the roles of managing.

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the word manage to the French—specifically, the word main, meaning “hand,” in reference to “the training, handling, and directing of a horse in its paces.”13 This is essentially the role of controlling, which is about handling and directing “subordinates” to ensure that they get their work done. But how do managers do this? To help answer this, we can turn to decision making.

Controlling through Decision Making Decision making is generally considered to be a thinking process in the head of the decider—in organizations, usually taken to be the manager. This may be true of many actual choices, but there is more to decision making than that. In fact, decision making can be seen as encompassing the various aspects of controlling.14

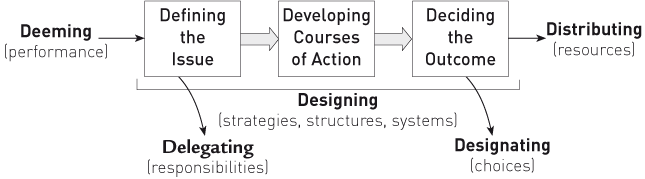

Consider the model of decision making shown in Figure 3.3 in three stages: (1) defining (and diagnosing) the issue, (2) developing possible courses of action to deal with it, and (3) deciding on the final outcome. Around these stages are shown five aspects of controlling, described next: designing, delegating, designating, distributing, and deeming.

Figure 3.3 CONTROLLING THROUGH DECISION MAKING

Designing The field of management’s most eminent thinker, Herbert Simon, considered designing to be the essential function of management: intervention to create or change something (1969).15 Managers sometimes engage in the design of tangible things, as when they head up a task force to develop a new product (which we shall discus on the action plane). Of concern here is designing the infrastructure of the unit, through strategies, structures, and systems to control the behaviors of its people.16

Designing Strategies A favored metaphor for the manager is “architect” of organizational purpose (Andrews 1987): the person who designs on paper so that everyone else can build—in the language of strategic management, formulates strategies for others to implement. This assumes that strategy making is a process of deliberate design, in order to control behavior. (In Chapter 5, we shall contrast this with strategy making as a process of emergent learning.)

Designing Structures Managers also design organizational structures: they divide up the work in their unit; allocate responsibilities for it to individual members; and then organize this around a hierarchy of authority, as depicted in those “organizational charts.” Such structures help to set people’s agendas, and so control their actions (see Watson 1994:32–33).

Designing Systems More directly, managers can take charge of designing, and sometimes even running, various systems of control in their units—concerning plans, objectives, schedules, budgets, performance, and so on. In fact, Robert Simons (1995) found in his research that corporate chief executives tend to select one such system (e.g., profit planning) and make it key to their exercise of control. In a similar vein, Morris et al. noted that the principals they studied “created and established a system for administering discipline in the school”—for example, using index cards so that “students learned there was a written record of their misbehavior” (1981:104). Note the “hands-off” nature of this form of controlling: the manager sets it up, and then the system does the controlling (much as deliberately designed strategies do the guiding).

Delegating In delegating, the manager assigns a task to someone else on an ad hoc basis: a specific individual is directed to carry out a specific activity. This is thus shown in Figure 3.3 as emanating from the first stage of decision making. In delegating, the manager identifies the need to get something done but leaves the deciding and the doing to someone else (perhaps reserving the right to authorize that person’s final choice).

The tricky thing about delegating is the dilemma noted in the last chapter (and discussed at length in Chapter 5): how to delegate when the manager, as nerve center, is better informed but lacks the time to do the task or even to pass on the information needed by someone else to do it.

Designating If delegating focuses on the first stage of decision making, then designating, including authorizing, focuses on the last stage—the making of specific choices. Sometimes these concern issues that just arise and can quickly be resolved, as when a manager authorizes or refuses a decision proposed by someone else in the unit. Of course, it is not necessarily that simple.

- Catherine Joint-Dieterle of the fashion museum was asked by her assistant about hiring someone for an open position. “Oh, no, I know this guy. I don’t want him,” she replied. But at her assistant’s insistence, she agreed to meet him, which she did later in the day. Then she hired him on the spot, commenting, “He’s been through a hard time—had to give him a break.” Many of the requests for authorization during the twenty-nine days came in administrative meetings, often about pending expenditures, as when Dr. Webb, head of the geriatric service in the hospital, met with his business manager: she was asking the questions, and he was giving quick short answers, mostly yes or no.

This designating can happen formally or informally, with the latter probably a lot more common and highly varied. Consider the comment by Andy Grove of Intel:

To be sure, once in a while we managers in fact make a decision. But for every time that happens, we participate in the making of many, many others, and we do that in a variety of ways. We provide factual inputs or just offer opinions, we debate the pros and cons of alternatives and thereby force a better decision to emerge, we review decisions made or about to be made by others, encourage or discourage them, ratify or veto them. (1983:50–51)

Distributing Distributing—namely, allocating resources as a result of other decisions—is a form of designating, too. But it merits separate attention because of its importance in managerial work.

Managers spend a good deal of time using their budgeting systems to allocate resources—money, materials, and equipment, as well as the efforts of other people. But they allocate resources in many other ways too—for example in how they schedule their own time and design the organization structures that determine how other people allocate their time.

Note that to treat something as a “resource” is to consider it as information—often numerical—for the purpose of control. So to “allocate resources” is to function on the information plane of managing, in the role of controlling. Indeed, treating employees as “human resources” means to deal with them as if they are information, not people: they get reduced to a narrow dimension of their whole selves. Later we shall discuss how much that today is considered interpersonal management on the people plane in fact reduces to the impersonal control of people on the information plane.

Deeming Finally we come to deeming, which has become an increasingly popular form of controlling these days, but hardly under that label. (“Management by objectives” is a better-known one.) By deeming, I mean imposing targets on people and expecting them to perform accordingly: “Increase sales by 10 percent,” or “Reduce costs by 20 percent”—and “Do it in my first hundred days.” The manager pronounces and then steps back. Indeed, such targets are often distant even from strategies themselves, since deeming is often favored when a manager lacks a clear frame. All too often, when managers don’t know what to do, they drive their subordinates to “perform.”

For much the same reason, a good deal of so-called strategic planning these days amounts to deeming. Treated as a formulaic process rooted in analysis rather than synthesis, strategic planning often discourages the creation of strategies, as managing gets reduced to “number crunching”—the setting of performance targets to drive behaviors (see my 1994 book The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning). “Increase sales by 10 percent” is not a strategy.

During the twenty-nine days, I observed several planning meetings that had little to do with strategy, more with organizing or budgeting, even scheduling, as discussed in the accompanying box.

I do not wish here to dismiss the setting of targets, which is often necessary, but rather to make the point that deeming cannot stand alone. Managers have to get beyond the targets—inside them, and past them, into the workings of their units. So-called stretch goals are fine so long as the manager puts some personal walk behind the general talk. Put differently, some deeming is fine; management by deeming is not.

Deeming is easy—too easy for managers who are out of touch. Targets are fine when combined with ideas. When not, they can demean organizations, which have to be managed as integrated wholes, not collections of disconnected parts.

To conclude, controlling, on the information plane, is important, but not when it is removed from the people and action planes or, worse, used as a replacement for other roles on these planes.

MANAGING WITH PEOPLE

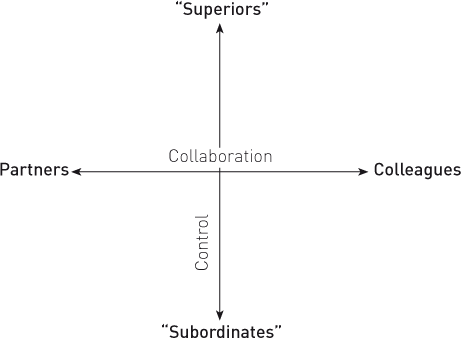

To manage with people, instead of through information, is to move one step closer to action but still to remain removed from it. On this plane, the manager helps other people make things happen: they are the doers.

Managing on the people plane requires a wholly different attitude from managing on the information plane. There the manager’s activities are instrumental, using information to drive people to specific ends. Here people are not driven so much as encouraged, often to ends they favor naturally. Thus, Linda Hill contrasted “I must get compliance for my subordinates” with “compliance does not equal commitment” (2007:3), and she continued later, “Management has just as much, if not more, to do with negotiating interdependence as it does with exercising formal authority…. ‘being a manager’ means not merely assuming a position of authority but also becoming more dependent on others,” insiders and outsiders—and more so in senior positions (2003:262).

“Strategic” Planning as Framing? Deeming? Scheduling?

At one point, Paul Gilding, the Executive Director of Greenpeace, was joined by two of his reports, Annelieke, who arrived with a big pile of flip charts, and Steve. (The full report of this day appears in the appendix.) Annelieke put up the charts, the first titled “Basic Planning Exercise,” and began explaining them. (The charts had labels such as “Finance and Implications of Strategic Planning,” “Political Structure,” and “Communication Structure.”) But Paul interrupted: “Before we start, what’s the aim of the whole exercise?” Annelieke answered: to have a work plan for the whole organization—who does what. As they discussed the charts, Paul commented, “We need to think through the Strategic Plan before implementation,” and “We should have performance targets for the Strategic Plan.”

Then Annelieke listed on the board, “(1) Objectives/mission; (2) Break down targets; (3) Communication,” and they discussed how to proceed. “Are we brainstorming or just going through it systematically?” she asked at one point, and remarked at another that “I think we should move on; we can discuss [campaigns, the first chart] for two days, I’m sure. Resource allocation [the second chart],” she announced.

Were these three directors of Greenpeace directing, let alone strategizing? They were certainly trying to get some order in their own heads, to come to grips with the complexities of directing Greenpeace. Yet strategy, whether as broad perspective or specific positions, was barely mentioned. The exercise seemed to reduce to decomposition: of the organization into a collection of parts and the charts into a collection of wishes. These managers were not getting strategy from structure any more than they were getting ideas from planning.

Maybe, therefore, planning is really about “prioritizing”—getting things into order for the purposes of deciding what has to be done when, which in the model of this chapter is called scheduling. As Aaron Wildavsky put it: “Alone and afraid, man is at the mercy of strange and unpredictable forces, so he takes whatever comfort he can by challenging the fates. He shouts his plans into the storm of life. Even if all he hears is the echo of his own voice, he is no longer alone. To abandon his faith in planning would unleash the terror locked in him” (1973:151–152).

After several decades of POSDCORB thinking and Tayloristic techniques, the Hawthorne experiments of the 1930s (Rothlesburger 1939) demonstrated with dramatic impact that management has to do with more than just the control of “subordinates.” People entered the scene, or at least they entered the literature, as human beings with concerns, and so to be “motivated” and later “empowered” by their managers. Influencing thus began to replace informing, and commitment began to vie with calculation. Indeed, by the 1960s and into the 1970s, the management of people, quite independent of the substance of their work, became a virtual obsession in the literature, through a succession of fashionable labels, such as “human relations,” “Theory Y,” “participative management,” “quality of work life,” and “total quality management.” And then came “human resources”—back we went.

For all this time, however, these people remained “subordinates”: “participation” kept them subordinate, because this was seen as being granted at the behest of the manager, still fully in control. And the later term empowerment did not change that, because the term itself indicated that the power remained with the manager. Truly empowered workers, such as doctors in a hospital, even bees in a hive, do not await gifts from their managerial gods; they know what they are there to do and just do it. You “have to be careful when talking ‘empowerment’” to the people working in the Banff National Park, Charlie Zinkan, its Superintendent, told me: “We have mechanics reading the Harvard Business Review!” As Len Sayles put it: “Intrinsic job satisfaction can only be obtained by the employees themselves. It can’t be handed out on a platter” (1964:53). In fact, a good deal of what is today called “empowerment” is really just getting rid of years of disempowerment (see Hales 2000 and Peters 1994:6).

People remained subordinates in another way, too. The focus of all this attention was on those inside the unit, who reported formally to its manager. Only after the beginning of serious research on managerial work did the obvious become evident: that managers generally spend at least as much time with people outside their units as they do with their own so-called subordinates. This section thus describes two managerial roles on the people plane: leading people within the unit and linking to people outside it.

Leading People Inside the Unit

When a specialist becomes a manager, the biggest change often is (or should be) the shift from “I” to “we.” Having become responsible for the performance of others, the first instinct, as Hill found out, is to think, “Good, now I can make the decisions and issue the orders.” Soon, however, comes the realization that “formal authority is a very limited source of power,” that to become a manager is to become “more dependent … on others to get things done” (2003:262). Enter the role of leading.

More has been written about leadership than probably all other aspects of managing combined. The United States, in particular, is obsessed with it, now more than ever. (When I went on the Harvard MBA website in 2007, I counted the words leader and leadership more than fifty times.) As Hill noted:

From their first days on the job, [the new managers] sprinkled the word “leadership” throughout their conversations, announcing, for example, that they intended to lead the organization. Leadership seemed to be a catch-all phrase. They were not [however] able to articulate with much confidence what they meant by it. (2003:105)

Find an organization with a problem and you will find all kinds of people proposing leadership as the solution. And if a new leader comes in and things improve, no matter what the cause (a stronger economy, a bankrupt competitor), they will have been proven right. This is part of our “Romance of Leadership” (Meindl et al. 1985).

Leadership can certainly make a difference. But it is no more the be-all and end-all than is controlling or strategizing. Leadership has to work alongside such other factors, plus especially “communityship,” to make an organization effective. In fact, many organizations these days could use less leadership (see Raelin 2000; Mintzberg 2004a).

The word leadership tends to be used in two different senses. The first is with regard to position and the led: the leader is in charge, motivates and inspires, elicits shock and awe, turns around ailing companies. This is where that distinction between leaders and managers comes in. It is also where those courses on “leadership” come in: spend a few days in a classroom or a couple of years in an MBA program, and (if you believe the hype) out you pop, all ready to exercise leadership. Try to do so, however, and you discover, as did the new managers Hill (2003:92) studied, that leadership is earned as well as learned, not granted.

In the second sense, leadership is seen more broadly, often beyond formal authority: a leader is anyone who breaks new ground, sets direction that shows others the way. A great inventor is a leader (even if he or she is a recluse); so is anyone who takes the lead in an organization, regardless of position, as in those stories about “skunkworks” that have changed companies.

I appreciate both views—we need all the creative direction setting we can get. But in this book and especially this chapter, I wish to describe leadership as a necessary component of management—specifically about helping to engage people in the unit to function more effectively. In this spirit, Lombardo and McCall have written about managers “who do not speak of themselves as leaders” so much as “taking leadership” in specific situations (1981:23); in the next chapter, in a section called “Managing beyond the Manager,” we shall discuss the second view of leadership.

Managers exercise such leadership with individuals, one-on-one, as the saying goes; with teams; and with the whole unit or organization, in terms of its culture. We shall begin with the individual, in two aspects: energizing people and developing them (see Raelin 2000:155).17

Energizing Individuals Call it what you like, managers spend a good deal of time helping to bring about more effective behavior on the part of their reports: they motivate them, persuade them, support them, convince them, empower them, encourage them, engage them. But perhaps all of this is better put another way: in the leading role, managers help to bring out the energy that exists naturally within people. To quote the words of a prominent CEO: “It’s not [the manager’s] job to supervise or to motivate, but to liberate and enable” (Max DePree of Herman Miller, 1990).

Developing Individuals Also on the individual level, managers coach, train, mentor, teach, counsel, nurture: in general, they help develop the individuals in their units. Again, the vast array of labels indicates just how much attention this aspect of leading has received. But again, the job of development is perhaps best seen as managers helping people to develop themselves. (For our own efforts in this regard, see www.CoachingOurselves.com.) And not only managers: consider these lovely words of two schoolteachers in Calgary: “We lose patience with the idea that the teacher is there mainly to ‘facilitate’ children’s development…. We are there for something more subtle and profound than that: we help mediate the knowledge, problems and questions the children already possess” (Clifford and Friesen 1993:19).

- This aspect of leadership came out most clearly in the days I spent in the refugee camps. Every “delegate” with the International Red Cross Federation, most of them experienced in disaster relief, had a “counterpart” in the Tanzanian Red Cross whom he or she trained. Abbas Gullet appeared to be spending a good deal of his time on such training, alongside the more regular tasks of reviewing performance, posting jobs, and interviewing applicants.18 (See the appendix for a full description of Abbas’s day.)

Sometimes as part of this developmental work, managers “do” in order to develop—in other words, they take action, not to get something done so much as to set an example for the taking of action by others. Andy Grove of Intel claimed that “nothing leads as well as example,” adding that “values and behavioral norms are simply not transmitted easily by talk or memo, but are conveyed very effectively by doing and doing visibly” (1983:52).

Building and Maintaining Teams On the group level, managers build and maintain teams inside their own units. This involves not only bonding people into cooperative groups but also resolving conflicts within and between these groups so that they can get on with their work. “The leader … is one who can organize the experience of the group—whether it be the small group of the foreman, the larger group of the department, or the whole plant … and thus get the full power of the group. The leader makes the team” (Follett 1949:12).

A great deal has been written about this, which, again, need not be repeated here. But one observation by Hill is worth mentioning. The new managers she studied initially conceived of their “people-management role as building the most effective relationships they [could] with each individual subordinate,” and so they “fail[ed] to recognize, much less address, their team-building responsibilities.” But over time, after mistakes, they realized the importance of this (2003:284).

Perhaps this occurs because “new managers get fooled” by organizational structure: “they assume that if all workers do their jobs according to some master plan or direction, there will be no need for contact or human intervention” (Sayles 1979:22). In other words, the controlling role will take care of the necessary coordination. Not so, wrote Sayles, and this was evident to me as Fabienne Lavoie worked to knit her nurses into a smoothly functioning team and Abbas Gullet brought the delegates and counterparts to work together in the refugee camps.

Hill (2003:289) cited Peter Drucker (1992) on the difference between managing people who play on a team (as in baseball) versus those who play as a team (as in football or an orchestra). Kraut et al. likewise commented on successful athletics teams that have an “almost uncanny ability to perform as a single unit, with the efforts of individual members blending seamlessly together.” Management as “a team sport … makes similar demands on its players” (2005:122).

Establishing and Strengthening Culture Finally, in the full unit, and more commonly for the chief executive of an entire organization, managers play a key role in establishing and strengthening the culture.

Culture is intended to do collectively what other aspects of the leading role do for individuals and small groups: encourage the best efforts of people, by aligning their interests with the needs of the organization. In contrast to decision making as a form of controlling, culture is decision shaping as a form of leading. “One principal roams the school reminding teachers and students of their duties and exhorting all participants in the learning process to strive for good work and exemplary performance” (Morris et al. 1982:691). John Cleghorn did much the same in the time he spent in the Royal Bank branches in Montreal, promoting the bank’s values to everyone who came his way.

Earlier the manager was described as the nerve center of information in the unit. Here the manager can be described as the energy center of the unit’s culture. As William F. Whyte put it in his classic study of street gangs:

The leader is the focal point for the organization of his group. In his absence, the members of the gang are divided into a number of small groups. There is no common activity or general conversation. When the leader appears, the situation changes strikingly. The small units form into one large group. The conversation becomes general, and unified action frequently follows. (1955:258)

In the 1980s, with the great success of the Japanese enterprises came a great deal of attention to what was seen as key to that success: corporate culture (e.g., Pascale and Athos 1981). But as Japan subsequently encountered economic difficulties, that message got lost; indeed, it was swamped by the rise of the bottom-line mentality (i.e., controlling). This was a mistake: the great enterprises remain those with the great cultures, in Japan and elsewhere. Just consider the enormous success of Toyota, a company that has remained largely faithful to the Japanese view of corporate culture.

Perhaps no one has written more eloquently about the manager’s role in building culture than sociologist Phillip Selznick, in a little book published in 1957 called Leadership in Administration. He used other labels, but his focus was clear: the leader shapes the “character of the organization”; he or she builds “policy” (now called strategy) “into the organization’s social structure” through the “institutional embodiment of purpose” and the infusion of the system “with value.” That is how an “expendable” organization becomes a responsive “institution.”19

Others have referred to this as the “management of meaning,” which obviously goes beyond the processing of information and even the development of strategy, to a sense of vision as the driving force of the organization as a community. Bolman and Deal have written that “the task of leaders is to interpret experience”: the lessons of history, what is happening in the world, and so forth, to “give meaning and purpose … with beauty and passion” (1991:43).20

In Mary Parker Follett’s words, leadership can transform “experience into power…. The ablest administrators do not merely draw logical conclusions from the array of facts of the past…. They have a vision of the future” (1949:52, 53), which helps “interpret our experience to us,” leading “us to wise decisions” instead of the leaders imposing “wise decisions upon us. We need leaders, not masters or drivers…. This is the power which creates community” (1920:229, 230).

Consider in this regard the queen bee in the hive: “She issues no orders; she obeys, as meekly as the humblest of her subjects, the naked power … we will term the ‘spirit of the hive’” (Maeterlinck 1901). But by her very presence, manifested in the emitting of a chemical substance, she unites the members of the hive and galvanizes them into action. In human organizations, we call this substance culture; it is the spirit of the human hive.

The culture of an organization may be rather difficult to establish, and to change—that can take years, if ever—but it can be rather easy to destroy, given a neglectful management. That is why the sustaining of culture was front and center on several of the days I spent with managers of long-established organizations:

- In the refugee camps, Abbas Gullet, as head of delegation and its most experienced member, was the carrier of the Red Cross culture, as concerned about getting others to appreciate it as he was in training for disaster relief. In a police force, we might expect to see a good deal of conventional controlling, in the form of rules, performance standards, and forms to fill out. There was no shortage of that on the days I spent with the three RCMP managers. But greater emphasis seemed to be put on culture: controlling behavior through the sharing of norms, based on careful socialization. Thus, Commissioner Inkster visited the officer training school and spoke extemporaneously for a half hour, followed by a blunt period of questions and answers.

To conclude this discussion of the role of leading, we can return to the metaphor of the leader as conductor, on the platform, fully in control. Does that actually constitute the exercise of leadership? Read the accompanying box.

Some Myths of the Conductor as Leader

In the conductor of the symphony orchestra, we have leadership captured perfectly in caricature. The great chief stands on the podium, with the followers arranged nearly around, ready to respond to every commend. The maestro raises the baton, and they all play in perfect unison. Another motion and they all stop. Absolutely in charge—a manager’s dream. Yet all of it is a perfect myth.

For one thing, as Bramwell Tovey, conductor of the Winnipeg Symphony, was quick to point out, this is an organization of subordination, and that includes the conductor. (See the appendix for the full description of Bramwell’s day, including his comments.) Mozart pulls the strings. Even that great maestro, Toscanini, was quoted as saying, “I am no genius. I have created nothing. I play the music of other men” (Lebrecht 1991: Chapter 4, p. 1). How else to explain the phenomenon of the “guest conductor”? Try to imagine a “guest manager” in almost any other kind of organization.21

Watching rehearsals reinforced this message. I saw a lot more action than affect. Bramwell Tovey was doing. Rehearsing is the work of the organization, and he was managing it directly, like the project that it really is. He was managing it for results: about pace, pattern, tempo, sound—smoothing it, harmonizing it, perfecting it. (Bramwell wrote to me later, in response to these comments: “In the traditional sense, I do most of my leading during performance, when, by means of physical gesture, I completely control the orchestra’s timing—and timing is everything.” For him perhaps, but hardly for most managers.) Here, if you like, he was orchestra operating, not orchestra leading, not even orchestra directing.

Yet if we have to get past leading in the foreground, then perhaps we need to place it in the background. Bramwell himself used the label “covert leadership.”22 As noted earlier, when asked about his leadership, Bramwell replied, “We never talk about ‘the relationship.’” Yet leadership was certainly on his mind: all that “doing” was influenced by various affective concerns—a feud between players, their sensitivities, aspects of the union contract, fear of censure in his role as first among equals.

Leading on the individual, team, and unit or organization-wide level can easily be distinguished in most managerial jobs. Not here.

As Bramwell made clear, direct leadership intervention concerning individuals was largely precluded during rehearsals. On the group level, there was something most curious here: a team of seventy people. Of course, there are “sections” within an orchestra, each with its own head, but these are players, not managers. When the orchestra plays, or even rehearses, there is only one manager, and only one team. So conventional team building is hardly possible. Bramwell said in jest at a presentation we later did together, “I don’t see my job as a manager. I look on it more as a lion tamer!” It was a good line that got a good laugh, but it hardly captures the image of seventy rather tame pussycats sitting in neatly ordered rows ready to play together at the flick of a wand.

That leaves culture building. What does this mean here? Seventy people come together for rehearsals and then disperse. When is the culture built? Again, perhaps covertly: through the energy, attitude, and general behavior of the conductor. But beyond this, culture is built into the very system. In other words, I was observing the culture, not just of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, but of symphony orchestras in general, developed over more than a century. So the culture of this particular orchestra did not have to be created so much as enhanced. “The conductor is no more than a magnifying mirror of the world in which he lives, Homo sapiens writ large” (Lebrecht 1991:5).

So beware, all you “leaders” (and leadership mavens). One day you may wake up to find that Bramwell Tovey is what a good deal of contemporary managing and its covert leadership is all about. Then you will have to step off your hierarchical podiums, lay down your budgetary batons, and get down on the ground, where the real work of your organization takes place. Only there can you and the others make beautiful music together.

Linking to People Outside the Unit

“Nothing legitimates and substantiates the position of leaders more than their ability to handle external relations. Above all else, leaders control a boundary, or interface” (Sayles 1979:38). Still on the people plane, linking looks out the way leading looks in: it focuses on the web of relationships that managers maintain with numerous individuals and groups outside their units, whether in other units of the same organization or outside of it entirely.

“When compared to non-managers, managers show wider organizational membership networks—they belong to more clubs, societies, and the like” (Carroll and Teo 1996:437). Homans (1958) referred to these as “exchange” relationships and Kaplan as “reciprocating” ones (1984)—see also his excellent description of what he called the managers’ “trade routes”—because the manager gives something in order to get something else in return, immediately, or as an investment in a sort of interpersonal bank.

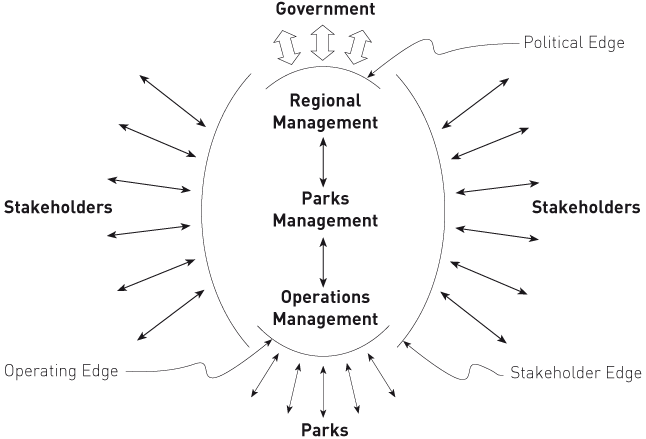

- The intricacies of linking were most evident during the days I spent with the three managers of the Canadian parks. As illustrated in Figure 3.4, they all managed on the edges—between their units and the external context—but in each case a different one. Sandy Davis, head of the western region, managed especially on a political edge, shown horizontally above her, particularly between her parks in western Canada and the administrators and politicians in Ottawa. She connected politics to process. Charlie Zinkan, head of the Banff National Park, who reported to Sandy, managed especially on a stakeholder edge, shown vertically to either side of him, as various outsiders brought pressures to bear on him. He connected influence to programs. And Gord Irwin, Front Country Manager in the Banff National Park, who reported to Charlie, functioned especially on an operating edge, between the operations and the administration, shown horizontally across the bottom of the figure. He connected action to administration.

It is surprising how little attention linking has received in the writings on management, despite the evidence from study after study, over several decades, that managers are external linkers as much as they are internal leaders (e.g., Sayles 1964; Mintzberg 1973; Kotter 1982a, 1982b). “The most important products of [the effective executives’] approach were agendas and networks, not formal plans and organizational charts” (Kotter 1982a:127). This lack of attention is even more surprising now given the extent to which contemporary organizations engage in alliances, joint ventures, and other collaborative relationships.23

Figure 3.4 MANAGING ON THE EDGES (in the Canadian parks)

Many of these linking relationships develop on a peer level; in other words, “social equals tend to interact with one another at high frequency” (Homans 1950:186). But they extend well beyond that, to include links with more senior people (including the managers’ own managers) and other staff and line people in the same organization, and a great many outsiders in the workflow (customers, suppliers, partners, union officials, etc.), as well as trade association and government officials, experts, community representatives, and a host of others.24 Morris et al., for example, found a school principal who “cultivate[d] … grandmothers”—neighborhood residents who knew the community well and so could act as “spotters” for the school, “warn[ing] him of unusual developments” (1982:689).

- A great variety of people linked to the managers during the twenty-nine days of observation. Fabienne Lavoie on the ward connected to doctors, patients, and families of patients. John Cleghorn lunched with financial investors of the Royal Bank, informing them for the purpose of influencing them, while Brian Adams had to work with partner companies of Bombardier from all over the world (Mitsubishi in Japan, BMW/Rolls-Royce in Europe, Honeywell in the United States, etc.). Marc, as head of the hospital, sat in a web of intense forces—his office almost felt like a state of siege. This included a government intent on cutting hospital expenditures and doctors who did not hesitate to go around him to members of the board. In the Red Cross camps, Abbas Gullet and Stephen Omollo interacted with their Tanzanian counterparts, NGO people, UN officials, representatives of refugees and the donor agencies, and by mail and phone with Red Cross officials in Africa and Switzerland.

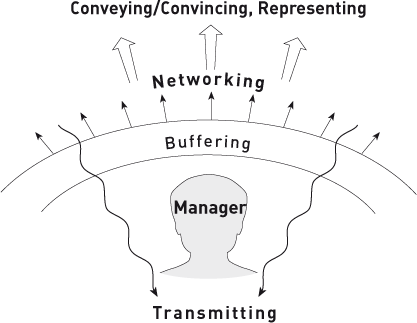

A model of the manager’s linking role is shown in Figure 3.5. It comprises the activities of networking, representing, conveying and convincing, transmitting, and buffering, each discussed in turn.

Figure 3.5 A MODEL OF LINKING

Networking One thing is clear. Networking is pervasive: almost all managers spend a good deal of time building up networks of outside contacts and establishing coalitions of external supporters. Kotter noted that the general managers he studied “all allocated significant time and effort early in their jobs [as well as later] to developing a network of cooperative relationships,” and that “the excellent performers … approached network building more aggressively and built stronger networks” (1982a:67, 117).

- Carol Haslam, Managing Director at the film company Hawkshead, brokered between customers and producers, drawing on what seemed to be an immense web of contacts and a finely tuned understanding of the British television industry. Her diary was thick, mostly because of a handwritten telephone directory of contacts. In the Red Cross, Abbas Gullet exhibited a particular ability to bridge, not only between English and Swahili as well as Africans and Europeans, but also between a head office in a wealthy European city and the delegation compound office in an impoverished African township. In Gouldner’s terms (1957), Abbas was a cosmopolitan and a local, able to combine his formal knowledge of the institution with his tacit knowledge of the situation.

Once again, it is enlightening to read two descriptions of this networking activity that are so remarkably similar even though one is about a president of the United States of America and the other about the leader of an American street gang.

[President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s] personal sources were the product of a sociability and curiosity that reached back to the other Roosevelt’s time. He had an enormous acquaintance in various phases of national life and at various levels of government; he also had his wife and her variety of contacts…. Roosevelt quite deliberately exploited these relationships and mixed them up to widen his own range of information. He changed his sources as his interests changed, but no one who had ever interested him was quite forgotten or immune to sudden use. (Neustadt 1960:156–157)

The leader [of the street gang] is better known and more respected outside his group than are any of his followers. His capacity for social movement is greater. One of the most important functions he performs is that of relating his group to other groups in the district. Whether the relationship is one of conflict, competition, or cooperation, he is expected to represent the interests of his fellows. The politician and the racketeer must deal with the leader in order to win the support of his followers. The leader’s reputation outside the group tends to support his standing within the group, and his position in the group supports his reputation among outsiders. (Whyte 1955:259–260)

Representing On the external front, managers play a figurehead role, representing their unit officially to the outside world, whether it be a company CEO presiding at some formal dinner, a university dean signing diplomas for graduating students, or a factory foreman greeting visiting customers. (Someone once said, only half in jest, that the manager is the person who meets the visitors so that everyone else can get their work done.) “[T]he President of the United States, besides being a leader of the political party in power, is ‘head of the Nation in the ceremonial sense of the term, the symbol of the American national solidarity’” (U.S. Committee Report, cited in Carlson 1951:24).25

- Bramwell Tovey spent the evening at the home of the most generous supporter of the orchestra, who was hosting “The Maestro’s Circle.” There he socialized with about fifty of the orchestra’s supporters, gave a short speech, and then entertained them at the piano. Detachment Commander Ralph Humble of the RCMP met with some local people to update them on the handling of a complaint, which he saw as a kind of public relations gesture.

Conveying and Convincing Managers use their networks to gain support for their unit. This may simply entail, on the information plane, conveying nerve center information to appropriate outsiders—for example, telling those grandmothers in the vicinity of the school to watch out for drug dealers. Or, on the people plane, managers seek to convince outsiders about what is important for their unit—for example, encouraging accounting to increase its budget, or using pageants to “orchestrat[e] community involvement” at school (Morris et al. 1981:78). In the popular vocabulary, managers champion the needs of their unit, lobby for its causes, promote its products, advocate on behalf of its values—and just plain peddle influence for it.26

- A good part of Rony Brauman’s day was spent in press and media interviews, representing the views of Doctors Without Borders on the situation in Somalia, to influence public opinion. He was “speaking out” more than just speaking. In N’gara, Stephen Omollo spent an hour and a half with Ben, a representative of the European Community Humanitarian Assistance office, who grilled him on the use of the funds it supplied for the Red Cross camps. At one point, Stephen said that 98 percent of the householders got the food they were supposed to get. “What actually ends up in their stomachs?” Ben wanted to know, as opposed to being bartered for sale or perhaps “taxed” away. Ben’s knowledge of the details and the conscientiousness with which he pursued his auditing responsibilities were impressive, but so were Stephen’s informed and articulate responses.

Transmitting Linking is a two-way street: managers who peddle influence out are the targets of influence coming in, a good deal of which has to be transmitted to others in the unit.

- For Brian Adams of Bombardier to get that new airplane in the air as promised, everything had to come together on a tight schedule. So he had to pass to his engineers the pressures that came to him from suppliers and his own senior management, to ensure that they were dealt with promptly. Likewise, Carol Haslam of Hawskhead had to ensure that the internal making of the films was responsive to the external concerns of the clients.

These activities of conveying, convincing, and transmitting can require a rather intricate blending of information and influence, values and visions. Years ago, the Greek economist (and later prime minister) Andreas Papandreou described the corporate chief executive as a “peak coordinator,” who consciously and unconsciously brings “the influences which are exerted on the firm” into some sort of “preference function” (1952:211). What form this might take is difficult to specify, but years earlier, Mary Parker Follett expressed the same idea more practically, and rather eloquently, in the case of a community leader:

He must be able to interpret a neighborhood not only to itself but to others…. He must know the great movements of the present and their meaning, and he must know how the smallest needs and the humblest powers of his neighborhood can be fitted into the progressive movements of our time…. He must be always alert and ever ready to gather up the many threads into one strand of united endeavor. He is the patient watcher, the active spokesman, the sincere and ardent exponent of a community consciousness. (1920:230–231)

Buffering It is in this combination of all these linking activities that we can especially appreciate the delicate balancing act that has to be built into the art and craft of managing. Managers are not just channels through which pass information and influence; they are also valves in these channels, which control what gets passed on, and how. To use two other popular words, managers are gatekeepers and buffers in the flow of influence. To appreciate the importance of this, consider five ways by which managers can get it wrong:

- Some managers are sieves who let influence flow too easily into their unit. This can drive their reports crazy, forcing them to respond to every pressure. We see this commonly these days when the demands of stock market analysts cause the chief executives of publicly traded companies to force everyone to manage for short-term performance.

- Other managers are dams who block out too much of the external influence—for example, from customers asking for product changes. This may protect the people inside the unit, but in so doing detaches them from the outside world—and external support.

- Then there are the sponges—managers who absorb most of the pressures themselves. This may be appreciated by others, but it is only a matter of time before these managers burn themselves out. I have seen this in some chiefs of hospital departments who are overprotective of the physicians.

- Managers acting as hoses instead put great pressure on the people outside, who may as a consequence become angry and less inclined to cooperate. This is common when a company squeezes its suppliers excessively.

- Finally, there are the drips, who exert too little pressure on the people outside, so that the needs of the unit are not well represented. Examples are those managers who ask too little of their suppliers and so get taken advantage of.

The effective manager may act in each of these ways some of the time but does not allow any of them to dominate all of the time. In other words, managing on the edges—the boundaries between the unit and its context—is a tricky business: every unit has to be protected, responsive, and aggressive, depending on the circumstances.

- A number of the managers I observed seemed to manage on the edges with a good deal of subtlety. Doug Ward, head of the CBC radio station in Ottawa, was “nudged” extensively by other parts of the organization, but he was quite clear on what to pass into his unit and what to hold back, also how to “nudge” back (e.g., about a proposed information system that he found questionable). “It’s nice having a job at the interface,” Doug said in response to a comment I made about such linking. The buffer par excellence was Marc, who protected his hospital and advocated for it aggressively. Had he acted as the government’s agent, or even that of the board, the hospital’s difficulties in coming to grips with its disparate inside forces would only have multiplied.

MANAGING ACTION DIRECTLY

If managers manage through information—conceptually, from a distance—and with people—closer, personally, with affect—then on a third plane they manage action directly: more actively, and concretely. Here we have a popularly recognized view of managing, at least in practice—“Mary-Anne is a doer”—if not in a literature that has long overemphasized controlling and leading.

Again, Len Sayles is one of the few to have insisted on the importance of this role (1964, 1979), alongside Tom Peters. The manager must be the focal point for action, Sayles argued, with direct involvement having to take precedence over the pulling force of leading and the pushing force of controlling. “The essence of management,” he wrote, is not “making key decisions, planning, and ‘motivating’ subordinates,” so much as “endless negotiations, trade and bargaining” as well as the “redirection of one’s own and one’s subordinates’ activities” (1964:259–260).

Linda Hill’s new managers recognized this only after they were well into their jobs. “When asked at the end of the first months, what is a manager, the new managers no longer responded ‘being the boss’ or ‘being the person in control.’ Instead, the most common observations included being a ‘trouble-shooter,’ a ‘juggler,’ and a ‘quick-change artist’” (2003:57). If, from a distance, managing looks like controlling on the information plane, then close up, getting involved on the action plane looms a lot larger.

- Catherine Joint-Dieterle of the fashion museum played a major role in the bringing in of new garments and reviewing each as it arrived; she was personally involved in the public tours of the museum; she wrote the proposals for new exhibitions. This was unlike Carol Haslam, head of Hawskhead, who did the deals but let others make the films.

We have seen repeatedly in this chapter that the most common managerial roles have generated many vernacular expressions. And so it is here, too. Managers “champion change,” “manage projects”; “fight fires”; “do deals.” Some of this pertains to actions taken within the unit, discussed here as doing on the inside; some others happen beyond the unit, discussed as dealing on the outside.

Doing on the Inside

What does it mean for a manager to be a doer? Many managers, after all, hardly “do” anything. Some don’t even place their own phone calls. Watch a manager at work and what you see is a lot of talking and listening, not doing.

Doing in the context of managing usually means almost doing—that is, getting close to the taking of action: managing it directly, rather than indirectly by encouraging people or processing information. So the manager as “doer” is really the person who “gets it done,” as in the French expression faire faire (literally, “to make something get made”).