2

The Dynamics of Managing

I don’t want it good—I want it Tuesday.

Have a look at the popular images of managing—that conductor on the podium, those executives sitting at desks in New Yorker cartoons—and you get one impression of the job: well ordered, seemingly carefully controlled. Watch some managers at work and you will likely find something far different: a hectic pace, lots of interruptions, more responding than initiating. This chapter describes these and related characteristics of managing: how managers work, with whom, under what pressures, and so on—the intrinsically dynamic nature of the job.

I first described these characteristics in my 1973 book. None of them could have come as a shock to anyone who ever spent a day in a managerial office, doing the job or observing it. Yet they struck a chord with many people—especially with managers—perhaps because they challenged some of our most cherished myths about the practice of managing. Time and again, when I presented these conclusions to groups of managers, the common response was “You make me feel so good! While I thought that all those other managers were planning, organizing, coordinating, and controlling, I was constantly being interrupted, jumping from one issue to another, and trying to keep the lid on the chaos.”1

Knowing. And Knowing. Why should there have been such reactions to what these managers doubtlessly knew already? My explanation is that, as human beings, we “know” in two different ways. Some things we know consciously, explicitly; we can verbalize them, often because we have so often read or heard about them. Other things we know viscerally, tacitly, based on our experience.

Surely we function best when these two kinds of knowing reinforce each other. In managing, they have all too often contradicted each other, requiring managers to live a myth—the folklore of planning, organizing, and so on, compared with the facts of daily managing. So if we wish to make significant headway in improving the practice of managing, we need to bring the covert reality in line with the overt image. That is the intention of this chapter.

Characteristics Then and Now

In this chapter I draw extensively on the conclusions of my earlier book because subsequent research has almost universally supported these conclusions. For example, in a parallel study of four senior executives a decade later, three from the same industries of my study, Kurke and Aldrich reported “an amazing degree of similarity” and called the original conclusions “surprisingly robust” (1983:977).2 I will cite some of these studies as we go along and also use evidence from the twenty-nine days of my later research to illustrate these characteristics.3 They are as follows:

• The unrelenting pace of managing

• The brevity and variety of its activities

• The fragmentation and discontinuity of the job

• The orientation to action

• The favoring of informal and oral forms of communication

• The lateral nature of the job (with colleagues and associates)

• Control in this job as covert more than overt

As noted in the last chapter, the basic processes of managing do not change much over time, these characteristics perhaps least of all. At the end of this chapter, I shall discuss the one development that should be having a significant impact—the new information technologies (IT), especially e-mail. My conclusion is that they are not so much changing the job as reinforcing these long-standing characteristics, all too often driving them over the edge.

As we go along, I identify a number of conundrums associated with these characteristics as a prelude to probing into each in Chapter 5.

Folklore: The manager is a reflective, systematic planner.

We have this common image of the manager, especially in a senior job, sitting at a desk, thinking grand thoughts, making great decisions, and, above all, systematically planning out the future. There is a good deal of evidence about this, but not a shred of it supports this image.

Facts: Study after study has shown that

(a) managers work at an unrelenting pace; (b) their activities are typically characterized by brevity, variety, fragmentation, and discontinuity; and (c) they are strongly oriented to action.

The Managerial Pace The reports on the hectic pace of managerial work have been consistent, from foremen averaging one activity every forty-eight seconds (Guest 1956:478) and middle managers able to work for at least a half hour without interruption only about once every two days (Stewart 1967), to chief executives, half of whose many activities lasted less than nine minutes (Mintzberg 1973:33). “Over forty studies of managerial work dating back to the 1950s have shown that ‘executives just sort of dash around all the time’” (McCall, Lombardo, and Morrison 1988:55).

In my first study, I noted that the work pace of the chief executives I observed was unrelenting. They met a steady stream of callers and mail, from their arrival in the morning until their departure in the evening. Coffee breaks and lunches were inevitably work related, and ever-present people in their organization were ready to usurp any free moment. As one put it to me, the work of managing is “one damn thing after another.”

In his study of general managers, John Kotter (1982a) referred to the overall demands of this job as adding up to “a particularly stressful situation and a very difficult time management problem,” within “a rapid-pace, high-pressure environment.” Here is how one manager put it:

I feel guilty that I’m not doing the things that the management educators, trainers, and the things I read say that I should be doing. When I come out of one of these sessions, or after reading the latest management treatise, I’m eager and ready to do it. Then the first phone call from an irate customer, or a new project with a rush deadline, falls on me, and I’m back in the same old rut. I don’t have time for time management. (Barry, Cramton, and Carroll 1997:26–27)

The work of managing an organization is just plain taxing. Morris et al., for example, found that most of the school principal’s days were “spent on the run” (1982:689). The quantity of work to be done, or at least that managers choose to do during the day, is substantial, and after hours senior managers appear able to escape neither from a situation that recognizes the power of their position nor from their own predispositions to worry about outstanding concerns.

Why do managers exhibit such paces and workloads? One reason has to be the inherently open-ended nature of the job. Every manager is responsible for the success of the unit, yet there are no tangible mileposts where he or she can stop and say, “Now my job is finished.” The engineer completes the design of a bridge on a particular day; the lawyer wins or loses a case at some moment in time. The manager, in contrast, must always keep going, never sure when success is truly assured or that things might come crashing down (see Hill 2003:50). As a result, managing is a job with a perpetual preoccupation: the manager can never be free to forget the work, never has the pleasure of knowing, even temporarily, that there is nothing left to do.

The Fragmentation and the Interruptions Most work in society involves specialization and concentration. Engineers and programmers can spend months designing a machine or developing some software; salespeople can devote their working lives to selling one line of products. Managers can expect no such concentration of efforts.

The search for patterns in managerial work—during the day, across the week, over the year—has not found much, aside from a few budgeting periods, and the like. One study of university presidents (Cohen and March 1974:148) noted that they tended to do administrative tasks early in the day and the week, and external and political tasks later, which is not terribly revealing. More so was a comment by Lee Iacocca about his highly visible CEO job: “Some days at Chrysler, I wouldn’t have gotten up in the morning if I had known what was coming” (Iacocca, Taylor, and Bellis 1988). A surprising finding of my own initial study is that few of the chief executives’ meetings and other contacts were held on a regularly scheduled basis. On average, thirteen out of fourteen were ad hoc.

What we find is a great deal of fragmentation in this work, and on top of that much interruption. Someone calls about a fire in a facility; a few e-mails are then scanned; an assistant comes in to inform about a challenge from a consumer group; then a retiring employee is ushered in to be presented with a plaque; after that it’s more e-mails; and soon it’s off to a meeting about a bid for a large contract. And so it goes. Most surprising is that the significant activities seem to be interspersed with the mundane in no particular pattern; hence, the manager must be prepared to shift moods quickly and frequently.

There are usually some longer meetings in most managers’ days, but in my study even many of these tended to get cut short.4 And they were typically surrounded by many shorter events—quick phone calls, short stints of desk work, spontaneous encounters in the office, trips down the hall, and so forth.

Carlson, in his 1940s study of Swedish managing directors, found that they could barely get twenty-three minutes without interruption once every third day “All they knew was that they scarcely had time to start on a new task or to sit down and light a cigarette before they were interrupted by a visitor or a telephone call” (1951:73–74). Aside from that cigarette, would Carlson find anything different today?

Two studies (Horne and Lupton 1965; Stewart et al. 1994) concluded that there is more fragmentation of managerial work at lower levels in the hierarchy, which is consistent with the Guest finding about foremen averaging forty-eight seconds per activity. And I saw something similar in the day I spent with the head nurse of the hospital ward. But two other first-line managers I observed in this later study—the Front County Manager of the Banff National Park and the Detachment Commander of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police—did not so stand out, while several of the chief executives I observed did, including the heads of Doctors Without Borders and the film company in London. Indeed, perhaps the most fragmented day I witnessed was that of another chief executive, the co-owner of the chain of telephone stores. I counted 120 distinct activities, among them the following sequence:

• At 9:28, Max chats with Lorne, just outside the door, about a soldering problem on some telephones and then turns back to Traci, his assistant, to continue going through the pile of papers. Just then Pierre walks by, and Max requests that he not proceed with some plan, and fifteen seconds later, it is back to Traci with “OK, let’s continue.” Then Monique, who deals with Accounts Payable, sticks her head in to report back on an earlier request, and seconds later it is back to Traci. Anna, who deals with customer and store service, puts her head in to report with great joy that she has solved a problem. It’s now 9:35—seven minutes have passed! (In a later meeting, the controller of the company said to Max, “Let me get a pad. You’re throwing so many things at me I have to write it down.”)

Carlson concluded in his early study (1951) that managers could free themselves from interruptions by making better use of their secretaries and being more willing to delegate work. But he begged an important question: is brevity, variety, and fragmentation forced on the managers, or do they choose this pattern in their work? My answer is yes—both times.

The five chief executives of my earlier study appeared to be properly protected by their secretaries, and there was no reason to believe that they were inferior delegators. In fact, there was evidence that they sometimes preferred interruption and denied themselves free time. For example, they—not the other parties—terminated many of their meetings and telephone calls, and they themselves often interrupted their quiet desk work to place telephone calls or to request that people come by. One chief executive I studied located his desk so that he looked down a long hallway. The door was usually open, and his reports were continually coming into his office.5

Why this preference for interruption? To some extent, managers tolerate interruptions because they do not wish to discourage the flow of current information. Moreover, they may become accustomed to variety in their work, and so boredom develops easily.

More to the point, however, managers seem to become conditioned by their workload: they develop a sensitive appreciation for the opportunity cost of their own time—the benefits forgone by doing one thing instead of attending to another. They are also acutely aware of the ever-present assortment of obligations associated with their job—the mail that cannot be delayed, the callers that must be received, the meetings that require their participation. Managing, wrote Leonard Sayles in his study of American middle managers, is like “‘keeping house’ . . . where the faucets almost always drip and dust reappears as soon as it’s wiped away” (1979:13).

In other words, no matter what they are doing, managers are plagued by what they might do and what they must do. As the head of a British football (soccer) association commented after the fans had been rioting on the continent: “In this job, one has to be permanently worried!” The realities of their job encourage some particular personality traits: to overload themselves with work, to do things abruptly, to avoid wasting time, to participate only when the value of participation is tangible, to be careful about too much involvement with any one issue. To be superficial is an occupational hazard of managerial work, certainly compared with the specialized work most managers did before they went into this job. To succeed, managers have to become proficient at their superficiality.

It has been said that an expert is someone who knows more and more about less and less until finally he or she knows everything about nothing. The manager’s problem is the opposite: knowing less and less about more and more until finally he or she knows nothing about everything. We shall return to this “Syndrome of Superficiality,” as well as other conundrums associated with these characteristics of managerial work, in Chapter 5.

The Action Orientation Managers like action—activities that move, change, flow, are tangible, current, nonroutine. Don’t expect many to spend a lot of time debating abstract issues at work; most prefer to focus on the concrete. And don’t expect to find much general planning in this job, or open-ended touring; look instead for tangible delving into specific concerns. Even when it comes to scheduling, “One should never ask a busy executive to promise to do something e.g. ‘next week’ or even ‘next Friday.’ Such vague requests do not get entered into [the] appointment diary. No, one has to state a specific time, say, Friday 4:15 P.M., then it will be put down and in due course done” (Carlson 1951:71).

I found in my earlier study that mail processing was treated as a burden. Why? Because little of it was actionable. In those days, it was slow, too. E-mail has certainly changed that—now even the mail has become actionable. But as we shall discuss at the end of this chapter, this may be deceiving.

Managers like current information. It often receives top priority, interrupting meetings, rearranging agendas, and evoking flurries of activity. Of course, current information can be less reliable than that which has had a chance to settle down, get analyzed, and be compared with other information. But managers are often willing to pay this price in order to have information that is up-to-date.

If managers are so action oriented, how do they plan? Snyder and Glueck challenged my conclusion in the 1973 book that “managers do not plan” (1980:76), essentially by pointing out from their study that managers think ahead and consciously interrelate activities. Certainly they do. Managers all plan; we all plan. But that does not make managers the systematic planners depicted in so much of the traditional management literature: people who lock their doors and think great thoughts. Leonard Sayles is worth quoting at length in this regard:

We . . . prefer not to consider planning and decision making as separate, distinct activities in which the manager engages. They are inextricably bound up in the warp and woof of the interaction pattern and it is a false abstraction to separate them. A good example of this is Dean Acheson’s description of what he believed to be the naïveté of the then new Secretary of State [John Foster] Dulles’ expectations concerning his job: “He told me that he was not going to work as I had done, but would free himself from involvement with what he referred to as personnel and administrative problems, in order to have more time to think. . . . I wondered how it would turn out. . . .” Later in this same essay, Acheson [commented]: “This absorption with the Executive as Emerson’s ‘Man Thinking,” surrounded by a Cabinet of Rodin statues bound in an oblivion of thought . . . seemed to me unnatural. Surely thinking is not so difficult, so hard to come by, so solemn as all this. (1964:208–209)

So the real planning of organizations takes place significantly in the heads of its managers and implicitly in the context of their daily actions, not in some abstract process reserved for a mountain retreat or in a bunch of forms to fill out. This means the plans exist largely as intentions in their heads—a kind of agenda off-line, if you like (off that line). Of course, this raises the big question: how are managers to think strategically, to see the “big picture,” take the long view? That, again, will be taken up in the conundrums of Chapter 5.

To conclude this point, managers appear to adopt particular activity patterns because of the nature of their work. This is an environment of stimulus-response, encouraging in the incumbent a clear preference for live action. The pressures of the managerial environment do not encourage the development of reflective planners, the classical literature notwithstanding. This job breeds adaptive information manipulators who prefer the live, concrete situation.

Folklore: The manager depends on aggregated information, best supplied by a formal system.

In keeping with the classical image of the manager perched on a hierarchical pedestal, managers are supposed to receive their important information from some sort of comprehensive, formalized management information system (MIS). But this has never proved true, not before computers, not after they appeared, not even in these days of the Internet.

Fact: Managers tend to favor informal media of communication, especially the oral ones of telephone calls and meetings, also the electronic one of e-mail.

Consider two surprising findings from earlier studies of managerial work, the first from Carlson on the Swedish managing directors:

The only complaint heard from some of the chief executives [about the system of internal reports they received] was that the number or size of the reports had a tendency to grow more and more, and that it had become impossible to read them all. . . . These reports . . . form a part of that paper ballast on the executive’s desk or in his briefcase, which is the cause of so much mental agony. (1951:89)

This study was done just when the first computer was being invented. Think of all the reports today! Second is this comment from a study of MIS managers themselves:

Mintzberg . . . found that chief executive officers placed little reliance on formal information sources. The results reported here, ten years later, suggest a quite similar phenomenon for information systems managers. These managers rarely referred to computer based information systems. . . . Like the shoemaker’s children, information systems managers seem to be among the last to directly benefit from the technology they purvey. (Ives and Olson 1981:57)

Oral Communication My earlier study and others found managing to be between 60 and 90 percent oral. One CEO I studied looked at the first piece of “hard” mail he received all week—a standard cost report—and put it aside with the comment, “I never look at this.” It was much the same for the paper mail sent out, with another CEO commenting, “I don’t like to write memos, as you can probably tell. I much prefer face-to-face contact.” Another said, “I try to write as few letters as possible. I happen to be immeasurably better with the spoken word than with the written word.”6 (E-mail has certainly changed that. But here we are discussing informal information, and e-mail, if not its attachments, is often informal too—for example, done more quickly than conventional mail.)

It should be emphasized that, unlike other workers, the manager does not leave the telephone, the meeting, or the e-mail to get back to work. These contacts are the work. The ordinary work of the unit or organization—producing a product, selling it, even conducting a study or writing a report—is not usually undertaken by its manager. The manager’s productive output has to be gauged largely in terms of the information he or she transmits orally or by e-mail. As Jeanne Liedtka of the Darden School has put it (in a talk I attended): “Talk is the technology of leadership.”

Soft Information The managers I studied seemed to cherish soft information. Gossip, hearsay, and speculation form a good part of the manager’s information diet. Why? The reason appears to be its timeliness; today’s gossip can be tomorrow’s fact. The manager who is not accessible for a quick message or an e-mail advising that the firm’s biggest customer was seen golfing with its main competitor may read about it as a dramatic drop in sales in the next quarterly report. But then it’s too late.7 As one manager put it: “I would be in trouble if the accounting reports held information I did not already have” (in Brunsson 2007:17). Of course, plenty of managers have been in such trouble of late, and this point helps to explain why.

Consider these words of Richard Neustadt, who studied the information-collecting habits of Presidents Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower.

It is not information of a general sort that helps a President see personal stakes; not summaries, not surveys, not the bland amalgams. Rather . . . it is the odds and ends of tangible detail that pieced together in his mind illuminate the underside of issues put before him. To help himself he must reach out as widely as he can for every scrap of fact, opinion, gossip, bearing on his interests and relationships as President. He must become his own director of his own central intelligence. (1960:153–154; italics added)

Formal information is firm, definitive—at the limit, it comprises hard numbers and clear reports. But informal information can be much richer, even if less reliable. On the telephone, there is tone of voice and the chance to interact. In meetings, there is also facial expressions, gestures, and other body language. Never underestimate the power of these. E-mail does not offer these advantages, but it is a lot faster than conventional mail, and so is somewhat more interactive.8

Personal Access In our master’s program for practicing managers (www.impm.org), the participants pair up and spend a week on “managerial exchanges” at each other’s workplaces. Time and again, managers who have gone to a foreign place where they did not speak the language reported on how rich was their learning, because they had to focus on these other aspects of communicating. I also heard a story about an employee at the Swiss office of an American company. She was disliked by the people at headquarters because she kept “demanding” this and that in her e-mails. Only when she visited the head office personally was the problem understood: she was misusing the word demander, which in French means “to ask.”

This raises an important concern: those people working in close vicinity of their manager, because of face-to-face access, can communicate more effectively and so be better informed than others at a distance. We can talk all we like about a global world, but most organizations—even the most international of corporations—tend to remain rather local at their headquarters.

Of course, managers can always get into airplanes to meet others and find out personally what is going on. Tengblad noted that the Swedish CEOs he studied in the international companies were inclined to do just that, “despite the emergence of faster means of communication” (2002:549). But that takes time (as Tengblad noted), especially compared with banging out an e-mail. So the danger may be to stay home and communicate electronically.

The Real Data Banks Two other concerns should be noted here as well. First, the types of information that managers favor tend to be stored in human brains. Only when written down can it be stored in electronic brains. But that takes time, and managers, as noted, are busy people. Even in their e-mails, the short reply seems generally to be favored over the more extensive debrief. As a consequence, the strategic data banks of organizations remain at least as much in the heads of their managers as in the files of their computers.

This raises the second concern. The managers’ extensive use of such information helps to explain why they may be reluctant to delegate tasks. It is not as if they can hand a dossier over to someone; they must take the time to “dump memory”—to tell that person what they know about the subject. But this could take so long that it may be easier just to do the task themselves. And so a manager can be damned by his or her own information system to a “dilemma of delegation”—to do too much alone, or else to delegate to others without adequate briefing. We shall return to this conundrum, too, in Chapter 5.

Folklore: Managing is mostly about hierarchical relationships between a “superior” and “subordinates.”

No one quite believes this statement, of course—we all know that plenty of managing happens outside and across hierarchies. But our very use of the awful labels of “superior” and “subordinate” does say something, just as does our obsession with leadership, the ubiquitousness of the label “top” management, and those stiff organizational charts. As Burns put it back in 1957, in a comment we have yet to fully appreciate: “The accepted view of management as a working hierarchy on organization chart lines may be dangerously misleading. Management simply does not operate as a flow of information up through a succession of filters, and a flow of decisions and instructions down through a succession of amplifiers” (p. 60).

Fact: Managing is as much about lateral relationships among colleagues and associates as it is about hierarchical relationships.

The management literature has long slighted the importance of lateral relationships in managerial work, and it continues to do so.9 Yet study after study has shown that managers generally spend a great deal of their contact time—often close to half or more—with a wide variety of people external to their own units: customers, suppliers, partners, government and trade officials, and other stakeholders, as well as all kinds of colleagues in their own organization with whom they have no direct reporting relationship.

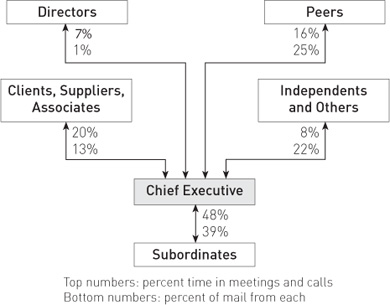

Figure 2.1 shows the breakdown of contacts via meetings, telephone calls, and mail for the chief executives of my earlier study. I found that these CEOs developed extensive networks of informers, who sent various reports and informed them of the latest events and opportunities. In addition, they maintained contacts with many experts (consultants, lawyers, underwriters, etc.) to provide specialized advice. Trade organization people kept them up-to-date on events in their industry: the unionization of a competitor, the state of impending legislation, the promotion of a peer. And as a consequence of their personal reputations and that of their organizations, these CEOs were fed with unsolicited information and ideas—a suggestion for a contract, a comment on a product, a reaction to an advertisement.

Figure 2.1 CHIEF EXECUTIVE CONTACTS (from Mintzberg, 1973:46)

One might expect this of chief executives. But studies of other managers, in middle and even first-line positions, bear evidence of similar ranges and varieties of contacts. I noted this for a number of managers of my later study—for example, Brian Adams of Bombardier, whose job I described as lateral management with a vengeance. He had enormous responsibility yet not a great deal of formal authority over many of the people he had to work with in the “partner” organizations (subcontractors, responsible for parts of the aircraft). Likewise, Charlie Zinkan, who ran the Banff National Park, sat between all sorts of interests—developers, environmentalists, and so forth—and had to respond to many of them, as delicately as possible. (The full days of both are described in the appendix.)

We might thus characterize the manager’s position as the neck of an hourglass, sitting between a network of outside contacts and the internal unit being managed. The manager receives all kinds of information and requests from insiders and outsiders, which are scanned, absorbed, and passed on to others, again both inside and outside the unit.

Folklore: Managers maintain tight control—of their time, their activities, their units.

The orchestra conductor standing on the platform waving the baton has, as noted, been a popular metaphor for managing. Here is how Peter Drucker put it in his 1954 classic book, The Practice of Management:

One analogy [for the manager] is the conductor of a symphony orchestra, through whose effort, vision and leadership, individual instrumental parts that are so much noise by themselves, become the living whole of music. But the conductor has the composer’s score: he is only interpreter. The manager is both composer and conductor. (pp. 341–342)

Drucker certainly spent a lot of time interviewing managers, but not (so far as I know) watching them conduct their work all day long. Sune Carlson did, and he came up with a rather different metaphor to describe what he saw:

Before we made the study, I always thought of a chief executive as the conductor of an orchestra, standing aloof on his platform. Now I am in some respects inclined to see him as the puppet in the puppet-show with hundreds of people pulling the strings and forcing him to act in one way or another. (1951:52)

I often read these two quotes, and a third, to groups of managers and ask them to vote on which best describes their work. But they have to vote after I read each, before they have had a chance to hear the others. I add, however, that they can vote up to three times. How would you have voted on these two: For the first? The second? Both? Neither?

The orchestra conductor usually gets some hands, not too many (people are suspicious), and the puppet gets a few as well, hesitantly. Then I read the third quote, from Leonard Sayles—back to the orchestra conductor, but not as Drucker saw it:

The manager is like a symphony orchestra conductor, endeavoring to maintain a melodious performance in which the contributions of the various instruments are coordinated and sequenced, patterned and paced, while the orchestra members are having various personal difficulties, stage hands are moving music stands, alternating excessive heat and cold are creating audience and instrumental problems, and the sponsor of the concert is insisting on irrational changes in the program. (1964:162)

Fact: The manager is neither conductor nor puppet: control to the extent possible tends to be covert more than overt, by establishing some obligations to which the manager must later attend and by turning other obligations to the manager’s advantage.

If managerial work is like orchestra conducting, a point I investigated in my day with Bramwell Tovey of the Winnipeg Symphony (see the Appendix), then it is not the grand image of performance, where everything has been well rehearsed and everyone is on his or her best behavior, the audience included. It is rehearsal, where all sorts of things can go wrong and must be corrected quickly.

In my earlier study, I found that the chief executives initiated a little less than a third (32 percent) of their own oral contacts (meetings and calls) and sent only about one piece of correspondence for every four they received (26 percent), almost all of them responses. (I have found no subsequent, comparable data for e-mail.) The content of these meetings and calls appeared likewise to be more passive than active (42 percent vs. 31 percent, the rest in between)—for example, engaging in a ceremonial event versus negotiating a contract. In his study of U.S. presidents, Neustadt concluded:

A President’s own use of time, his allocation of his personal attention, is governed by the things he has to do from day to day: the speech he has agreed to make, the fixed appointment he cannot put off, the paper no one else can sign, the rest and exercise his doctors order. . . . A President’s priorities are set not by the relative importance of a task, but by the relative necessity for him to do it. He deals first with the things that are required of him next. Deadlines rule his personal agenda. (1960:155)

But does all this tell the whole story? Do the findings that many of managers’ meetings are set up by others, that they receive more mail than they generate, that they can be inundated with requests and are slaves to their appointment diaries, indicate that they are puppets who do not control their own affairs? Not at all. The frequency of requests, for example, may be a good measure of the status a manager has established for him- or herself, while the quantity of unsolicited information received may indicate the manager’s success in building effective channels of communication.10

• I was struck by Marc, the head of the hospital, who faced enormous pressures, especially from a cost-conscious government on the outside and demanding physicians on the inside. The politics in and around any hospital can be intense. I referred to this day as “a state of siege.” Yet Marc fought back, using every manner of maneuver to gain some control. Some of the other managers among the twenty-nine who seemed to be even more constrained, in fact, proved to be among the most proactive. (In Chapter 5, we shall discuss Peter Coe of the National Health Service of England, as he “managed out of the middle.”)

Effective managers thus appear to be neither conductors nor puppets—they exercise control despite the constraints.11 How do they do this? I concluded in my earlier study that they use two degrees of freedom in particular. They make a set of initial decisions that define many of their subsequent commitments (e.g., start a project that, once underway, demands their time). And they adapt to their own ends activities in which they must engage (e.g., by using a ceremonial occasion to lobby for their organization). In other words, managers create some of their obligations and take advantage of others.12

Perhaps this is what most clearly distinguishes successful and unsuccessful managers. The effective managers seem to be not those with the greatest degrees of freedom but the ones who use to advantage whatever degrees of freedom they can find (a point I shall develop in Chapter 4 and return to in Chapter 6). In other words, these people do not just do the job; they make the job. All managers appear to be puppets. Some decide who will pull the strings, and how, and then they take advantage of every move that they are forced to make. Others, unable to do so, get overwhelmed by this demanding job.13

The Impact of the Internet

There has been one evident change in recent times that should be having a great effect on all these characteristics of managing: the Internet, especially e-mail, a new medium of communication that has dramatically increased speed and volume in the transmission of information. Has its impact on managing been likewise dramatic?

Judging by all the e-mails flying about and the ambiguousness of BlackBerries, it would certainly seem so. But the question is whether this has changed managing fundamentally. And about this important issue there has so far been little evidence—a surprising finding in its own right.14 I will draw here on what I can, including studies from outside management, but my comments will necessarily have to be seen as speculative.

My answer is yes and no. No, because the Internet may be mostly reinforcing the very characteristics that have long been prevalent in managerial work, as discussed in this chapter. And yes, because this may be driving some of the practice of managing over the edge.

The Internet for Better and for Worse The advantages of the Internet are evident and quite astonishing. Managers can keep in current touch with people all over the world in ways that used to be unthinkable. They can also share large amounts of information with a great many people. These advantages enable them to greatly extend their informational networks and rather easily conduct their affairs across the globe.15

I needn’t dwell on these advantages; they are profound and evident to all of us. But what effect does the Internet have on managing itself?

Better-informed managers, able to communicate more quickly, can develop faster-moving, more competitive enterprises—so long as they can handle these changes. Some may be able to take them in stride; others may be drawn into acting more quickly and less thoughtfully—conforming more and considering less. I fear that there is a growing number of the latter.

The Media and Its Messages There are various aspects of the Internet; I will focus mainly on e-mail here, because that seems to be having the most direct impact on the practice of managing. (Of course, managers, like others, send large documents at the click of a key. But many of these documents are prepared by specialists, as are perhaps many of the Web searches required by a manager. But few managers these days escape the extensive use of e-mail.)

It is important to note, for starters, that this new medium remains thin. Like conventional mail, e-mail is restricted by the poverty of words alone: there is no tone of voice to hear, no gestures to see, no presence to feel—even images can be a nuisance to create. E-mail may simply limit the user’s “ability to support emotional, nuanced, and complex interactions” (Boase and Wellman 2006). Managing is as much about all these things as it is about the factual content of the messages.

The danger of e-mail is that it may give a manager the impression of being in touch while the only thing actually being touched is the keyboard. This can aggravate a long-standing problem in managing: allowing a fancy new technology to give the illusion of control. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was criticized by some of her military officers for trying to direct the Falklands war via the use of telex in London. Imagine if she had e-mail. The head of a major department of the Canadian government did have e-mail: he told me that he used it to communicate with his staff every morning. I feared for his managing. Relying on the rapidity of e-mail is fine, so long as the manager is not fooled into believing that he or she understands a situation because some words have popped up on a screen.

On the telephone, people can interrupt, grunt, pounce; in meetings, they can nod in agreement or nod off in distraction. Effective managers pick up on such clues. With e-mail, you don’t quite know how someone has reacted until the reply comes back, and even then you cannot be sure if the words were carefully chosen or sent in haste. Compare this with oral communication, where feelings are difficult to hide.16

So, does the Internet make managers better connected or less? Take your choice for now—we don’t yet know the answer. But we had better be asking the question.

Is the Global Village a Community? Marshall McLuhan (1962) wrote famously about the “global village” created by new information technologies. But what kind of a village is that?

In the conventional village, you chat with your neighbor at the local market: this is the heart of the community. In the global village, you click to send a message to someone on the other side of the globe, who you may never even have met. Like those fantasy-ridden love affairs on the Internet, such relationships may remain untouched and untouchable. In fact, Keisler et al. found that “people who communicated by computer evaluated each other less favorably than did people who communicated face-to-face” (1985:78). This is obviously not true for those electronic love affairs, so maybe the more accurate conclusion is that these detached forms of communication tend to exaggerate impressions of other people, one way or the other. The communicators, in other words, have little basis on which to judge each other.

Yet judging people is critically important to all managing. Organizations are communities, dependent on the robustness of their relationships. Trust and respect are absolutely key. So we have to be quite careful about this global village, not to confuse its networks with communities. The Internet may be enhancing networks while weakening communities, within organizations as well as across them.17 Thus, Boase and Wellman have written about “networked individualism,” where “people belong to more spatially dispersed and sparsely knit personal networks” (2006). Their point of reference is society in general, but this might help to explain the rise of the egocentric, heroic form of leadership that is wreaking so much havoc on today’s organizations.

Let’s now consider what may be the direct effects of the Internet on the characteristics of managing that have been discussed in this chapter.

The Pace and the Pressures One thing alluded to throughout this discussion seems certain: e-mail increases the pace and pressure of managing, and likely the interruptions as well.

Of course, many people do e-mail in batches. But with their preference for instant information, managers may be inclined to do it frequently, in brief spurts, plus leave the computer open so they can respond to “You’ve got mail!” Add a BlackBerry in the pocket—the tether to the global village—and you’ve got interruptions, galore. (I heard one story about a meeting called by e-mail at 10:30 Sunday evening for 8:30 Monday morning.)18

When the American and British publishers of this book read an early draft of this chapter, without this section, both e-mailed that I had to discuss the Internet, which is driving managers crazy. Steve Piersanti of Berrett-Koehler wrote (on June 21, 2005), “Managers are interrupted more than ever, but now the interruptions are the frequent [e-mails] . . . that demand their attention.” To quote another CEO, from a newspaper interview: “You can never escape. You can’t go anywhere to contemplate, or think” (CAE’s Robert Brown, in Moore 2006). Of course, you can go anywhere you wish in order to contemplate or think—if you choose to.

The Orientation to Action For managers, who already exhibit an orientation to action, nothing about e-mail suggests a reduction in that characteristic. Quite the contrary. It is an interesting irony that e-mail, technically removed from the action (picture the manager sitting in front of a screen), enhances the action orientation of managing. There is, after all, lots of fire and brimstone (so to speak) in those brains, computer and human, with all their electrons flying about.

The Oral Nature of Managing Of course, more time on the Internet can mean less time on everything else, which likely includes oral communication. There are only so many hours in every day. But then again, some of those hours have been devoted to sleep and to family, so we have to ask whether those have suffered as a result of the Internet. In other words, does the Internet just pile more pressures on top of an already pressured job? Do too many managers want it all?19

Again, we don’t have evidence on this, but there is room for suspicion. Even if the communication may be less oral, it can be more frenetic, and perhaps more superficial as well. And with this can come greater conformity—just to get it done fast.

The Lateral Nature of the Job People who report to a manager are few and fixed, in contrast to the network of people outside the unit that is far larger and potentially unlimited. So this new medium that makes it so easy to establish new contacts, and to keep “in touch” with the ones already established, likely encourages the extension of managers’ external networks at the expense of their internal communication.20

Might this weaken the strong ties a manager might otherwise have with the people in his or her own unit? With limited managerial time available, we might think so. (Consider the failures of so many financial institutions in 2008–2009.) Time in front of the screen is time not spent in front of someone down the hall. Indeed, as with that Canadian government manager, the person down the hall may now be the one on the screen.21

Control of the Job Finally comes perhaps the most interesting question of all: does the Internet enhance or diminish the control managers have over their own work? Obviously it depends on the manager: As with most technologies, the Internet can be used for better or for worse. You can be mesmerized by it, and so let it manage you. Or you can understand its power as well as its dangers, and so manage it. I have written this section of the book to encourage the latter.

Still, there may be pervasive effects overall. Think of the power of e-mail to connect, the power of the Internet to access and transmit information. Think, too, of the pressures and pace of managerial work, the needs to respond, the nagging feeling of being out of control. Might the Internet, by giving the illusion of control, in fact be robbing managers of control? In other words, are the ostensible conductors becoming more like puppets after all?

Over the Edge? Pinsonneault and Kraemer (1997) found something interesting in a study of 155 city governments: electronic communication reinforced already existing tendencies in the organization, specifically to centralize or else to decentralize. Might the same thing be true of the characteristics of managing? Combining this with just about every point thus far suggests one conclusion: the Internet is not changing the practice of management fundamentally; rather, it is reinforcing characteristics that we have been seeing for decades. In other words, the changes are in the same direction, of degree, not kind.

But the devil can be in the detail. Changes of degree can have profound effects, amounting to changes of kind. The Internet may be driving much management practice over the edge, making it so frenetic that it has become dysfunctional: too superficial, too disconnected, too conformist. In India, I watched the managers of a high-technology company on an international program go nuts when their e-mail connections went down for a couple of days. Were they unable to manage because they were suddenly out of touch? Or did the way they have come to manage put them out of touch with managing itself? Perhaps the ultimately connected manager has become disconnected from what matters, while this overactivity is destroying the practice of managing itself.

Normally Calculated Chaos

To conclude, in this chapter we have seen the characteristics of managing, as they were then and remain now: the pace, brevity, variety, fragmentation; the interruptions; the orientation to action; the oral aspect of the information; the lateral nature of much of the communication; and the tricky problem of exercising control without quite being in control.

Does all this suggest bad managing? Not at all. It suggests normal managing—inevitable managing. “When asked to describe what a manager does, the new managers spoke feelingly about the stresses in their new positions. Management seemed a world of overwhelming confusion, of overload, ambiguity, and conflict. . . . Above all, they were struck by the unrelenting workload and pace of being a manager” (Hill 2003:50). Some of these managers expected this to slacken. “Once I get my arms around the job or should I say if . . . everything will fall into place. Then I’ll be the coordinator, controller, not necessarily in that order, all the time” (p. 51). No such luck. Not even for those who make it to the so-called top, the “rapid-pace high-pressure environment” of the general managers that Kotter described.

But these characteristics are normal only within limits. Exceed them, and the practice of management can become dysfunctional. The Internet can cause this, but so can the characteristics themselves. We all know excessively frenetic managers. What one day seems normal can the next become hazardous.

Managing, even normal managing, is no easy job. A New York Times commentary on my original study (Andrews 1976) used two phrases that for me capture the nature of this well: “calculated chaos” and “controlled disorder.” They tell of the nuance that is all effective managing—compared with the “confusing chaos” of “naïve managers” (Sayles 1979:19). With this in mind, we turn now to the content of managing—what managers actually do—and return to how managers can deal with these pressures in Chapter 5.