p.7

For Those Respecting the Law, We Salute You. For the Rebels, There Is No Such Thing as Free Music

If an artist of any sort—visual, music, film, written word—wants their work protected so that they can earn money from their art, it is highly recommended that they copyright the work. This is merely registering the art with the U.S. Copyright Office so that the artist is protected from future infringements, or, more simply, from anyone using their work. It’s easy to register your work by going to www.copyright.gov. An application for copyright registration contains three essential elements: (1) a completed application form, (2) a non-refundable filing fee and (3) a non-returnable deposit—that is, a copy or copies of the work being registered and ‘deposited’ with the Copyright Office. When the Copyright Office issues a registration certificate, it assigns as the effective date of registration the date it received all required elements in acceptable form, regardless of how long it took to process the application and mail the certificate of registration.

Once your music or art is registered, you are then protected under U.S. copyright law from anyone using or incorporating parts or whole amounts of your work into theirs. Yet the proliferation of digital and social media platforms has rendered copyright law a mainstream issue with much considered debate. In today’s world it is easier to poach someone’s creative efforts, so much so that it has become relatively common. Copyright topics in the news vary widely from ownership disputes, extensions (the length of time a copyright is protected) and catalog valuations and acquisitions to infringement cases. Copyright law is the foundation of everything examined in this book. Without copyright protection, the creative endeavors of writers and producers would have no financial value. They would not be able to make a living. Therefore, the main reason one needs to clear or get permission to use music (the process of which is commonly called music rights clearance) is to secure a formal, legal license to use the music, because someone owns the underlying copyright and expects the licensee to recognize that and pay for that use.

p.8

While the breadth of copyright law is exhaustive and nuanced, the focus here will be on the purpose and basic principles that govern the issue. We’ll discuss the historical origins, meaning and terminology behind commonly used phrases as well as the monetary value associated with copyright use.

PURPOSE

Copyright protection is instituted to encourage people to keep producing creative work for public consumption. Creative output is maximized when creators can be rest assured their blood, sweat and tears are respected and protected, and not stolen. Copyright is an acknowledgment of authorship and ownership. With protections in place, creatives can keep recording, writing and publishing with peace of mind.

From a user’s perspective, copyright law serves an important role as well. Companies and media creators are able to use and incorporate the creation of others in their creative endeavors. More often than not, a producer comes to us having built his entire vision for a scene around the emotional elements of a piece of music. Creativity breeds creativity, so when an app developer is engineering a new game, or a filmmaker is envisioning a scene inspired by the work of another, the developer or filmmaker is able to incorporate that work into theirs and make something very special for their consumer and audience. Despite popular opinion, copyright law is not meant to hinder creativity. Quite the opposite; it’s intended to inspire it.

p.9

HISTORY

Like most of our legal system, U.S. copyright law is based on British law. The idea originally was to protect people from the copying and reselling of published writings. In 1790, Congress enacted the first U.S. copyright statute, which was authorized by a clause in the Constitution that specifically protected works of authorship. This grew out of a need to protect the creators and writers of books, text and speeches, and orators. ‘Works of authorship’ expanded to include visual arts, motion pictures, photographs and songs. With the invention of the phonograph record, sound recordings were also included, and, most recently, digital content can be copyrighted. As of this publication, we live under the copyright framework established by the 1976 Copyright Act. This framework has been amended and the term of protection has been extended, but many principles of the Act remain the same.

DURATION OF COPYRIGHT

Determining the length of copyright protection has its complexities. For works created after 1978, the term of copyright is the life of the author plus 70 years. Works made for hire, which cover works created and owned by corporations, have a different standard: either 95 years from the date of publication or 120 years from the date of creation, whichever expires first. Whether protection extends to foreign infringers is another consideration. In 1887, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (named after Berne, Switzerland, where the Convention was signed), defined the scope of international copyright protection.

Under the terms of the Convention, reciprocal copyright protection was granted automatically to all creative works from member countries. It took the United States over 100 years to become a party to the Convention. In 1989, the Convention established that an author is not required to register or otherwise apply for a copyright. As soon as the work is written or recorded, its author is automatically granted exclusive rights to the work until the copyright expires.

p.10

Figure 2.1 Berne Convention stamp, 1886

WHAT IS COPYRIGHTABLE AND WHAT ARE THE RIGHTS IT PROTECTS?

Protection under copyright law (title 17 of the U.S. Code, section 102) extends only to original works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible form. An ‘original work’ can be a book, a movie, a painting, a sculpture, songs, computer software and even architecture. ‘Authors’ or ‘creators’ can be writers, composers, visual artists, choreographers, filmmakers, architects, jewelry designers, musicians, and computer software programmers. They can be an individual, a corporation or a group of people. To be ‘fixed’ means it’s been written down, recorded or notated on sheet music.

Now that we know what can be copyrighted, let’s be clear on what cannot. Facts, ideas, systems or methods of operation are not copyrightable. Take a great tale of one man’s efforts as a heli-medic in Aboriginal New Zealand. Great story? Yes. Copyrightable? No. You can’t copyright a mere idea for a story. However, if the story is sufficiently ‘original’ you may be able to copyright the script.

p.11

Once an original work has been created and fixed, the copyright owner immediately acquires ownership of a number of important exclusive rights over that work. These unique rights include the right to reproduce, distribute, publicly perform, display publicly and make derivative works. Since these rights are owned and controlled by the copyright owner, any time a third party wishes to utilize one, the copyright owner must give permission, which is usually granted in the form of a license. A license is essentially an agreement, on paper, that states how, where, when and for what fee a user is allowed to use the piece of art or, in this case, music. Permission to use music copyrights has some commonly referred-to licenses. They are:

Mechanical License

This grants the user of music the right to reproduce a song in a physical or digital format via CD or digital download, provided the music has already been commercially released in the United States by the copyright owner. This is strictly for the audio reproduction of a song and does not pertain to any visual element that goes along with the audio. Let’s say one wants to record and sell a cover album of hit sounds from one’s high school years. A mechanical license would be required since the music is being performed in an audio-only format for release as a CD. Other examples include soundtrack albums and even karaoke use.

Public Performance License

This license grants permission for music to be heard in public spaces, such as on the radio or television, via on-hold music, or in an elevator, hair salon, local bar, or other places of work or even on a public website. This license is secured by public broadcasters, hence a radio station or television network, or a business establishment where music is heard. The licenses are generally granted on an annual basis, via a blanket license, so the venue has access to a ton of music, instead of licensing each song individually.

p.12

Synchronization License

This license grants permission to use a song which is locked to a moving image or other audio-visual body of work. This is the license that a filmmaker or media producer must secure when coupling images with music, since one is securing from the copyright owner the right to reproduction and distribution and the creation of a derivative work (i.e., the visual image which embodies the copyrighted material). Except for instances when a use is deemed ‘fair’ (which we will cover later in this chapter), almost every time a piece of music is paired with visual content a synchronization license has been secured through the copyright owner. Unlike the compulsory mechanical license or the blanket public performance license, a synchronization license needs to be negotiated almost every time.

MUSIC COPYRIGHT

Unfortunately, music copyright clearance is complex and unwieldy. The main reason being that, unlike other forms of art, there are at least two different entities to contact for clearance of a piece of recorded music. There is (1) the copyright holder of the recording and (2) the copyright owner of the underlying musical composition.

Why are there two copyrights? Well, because they are distinctively different. One protects the composition itself—which includes the music and lyrics—while the other protects a particular recorded version of that song. For example, let’s consider the classic love song, “I Will Always Love You.”

p.13

Figure 2.2 Dolly Parton cover “I Will Always Love You”—released 1974

Figure 2.3 Two sides of a coin

This song was written by Dolly Parton, and therefore she and her music publisher, Velvet Apple Music (BMI), own the copyright to the underlying musical composition. This song, however, has been recorded by dozens of artists, from Dolly Parton to LeAnn Rimes to Whitney Houston. Each of these recording artists, and their record labels, own the copyright in what is commonly referred to as the master of their particular recording of that song. This master copyright protects the sound recording and the creative efforts of the producer, sound engineers and background musicians. Therefore, when licensing the composition “I Will Always Love You” by Dolly Parton, it’s important to understand both the label and the publisher need to grant permission. In industry jargon, this means both sides need to clear the song for your use. Think of a coin with two sides: (1) the master recording is one side, and (2) the composition, often referred to as the ‘publishing,’ is the other side.

p.14

Both ‘sides’ then must agree to the use before the requesting party can move ahead. This is the most important aspect of music rights clearance: ‘one song, two rights.’ Every song has two separate copyrights:

1. Publishing copyright—This covers the intellectual property concerning the creation of a piece of music, commonly known as ‘songwriting credit.’

2. Master copyright—This covers the fixed audio record of a piece of music, including the performance and physical/digital recording of the song.

Although usually separate, there are some cases where the same entity controls both copyrights. More-independent companies such as Domino Music and Third Side Music usually sign an artist and then can represent both the publishing and master rights, or both ‘sides.’ When that happens the company is considered a one-stop shop, meaning that the user can obtain permission or clearance of both sides of the song at one company, rather than through a number of people. Music libraries such as Songtrdr and Pump Audio exist to do exactly that, i.e., be a one-stop for securing the music rights. Yet almost all popular commercial music will require a clearance from more than one entity.

FINDING THE COPYRIGHT OWNER

Copyright clearance can be tedious, in that owners are not always easy to locate or identify. As with any asset, rights switch hands. You can transfer and assign the right of a copyright at any time, so a copyright can be owned by one entity at the start of negotiations, and by the end controlled by a different entity, and hopefully not during the time of your project!

We worked with one client whose Oscar-nominated short had three songs in it that, when we initially cleared them, were affordable and cleared like butter. But then her film got greater distribution and we had to increase the rights she needed to cover all media. During the six-month lag period between the deals, the copyright holder for the famous song “New York New York,” EMI, was sold to Sony/ATV Music. The new owners elevated this composition to being one of their premiere catalog songs, and the cost skyrocketed to more than four times the original fee. We spent months trying in any way possible to bring the price down to a more manageable fee. Over time we were successful in doing so. However, a change of ownership can wreak havoc on all parties.

p.15

Another common situation is when a new artist or songwriter holds the copyright personally and has not yet sold their rights to a publisher. A publisher’s main role is to protect a copyright, exploit it and collect on the use of it. Most pay an up-front fee for a catalog of songs—previously recorded material or future songs—so they can control their use, instead of the songwriter overseeing the use of their music. They want the songwriter to focus on creating new material and leave the business aspects to the publisher.

To that end, a publisher and a label serve very similar core functions: chiefly, to earn money from the exploitation of their copyrights (a publisher on behalf of a song, and a label on behalf of a master recording). With revenue generation at the center of its business, a publisher is pressed to ensure all uses are properly licensed and therefore paid for. It’s usually a lot easier to negotiate a deal with an unsigned songwriter/artist. For an indie, deal-making is motivated by many factors, not just money. Exposure for a band, genuine interest in a project and basic support for other creative communities still mean something. But this is often lost when publishers enter the picture. Publishers need to recoup the advance paid to control a catalog. They also need to make sure numbers are met to appease stakeholders. To be fair, some writers retain what is called an approval right over certain uses—usually synch uses—in which the agent, publisher or label representing the songwriter or artist must seek their content prior to licensing the music.

Once, our office cleared a Lorde song and the negotiated deal was handled through Lorde’s management since she had yet to sign a publishing deal. By the time our client was ready to secure the license, the artist had inked a publishing deal with Songs Music Publishing, who then controlled the copyright to her music. Luckily for our client, this did not change the deal since the terms of use had been accepted and agreed to before she signed her publishing agreement. We were lucky in this case and timing was on our side.

p.16

The most laborious deal is when permission needs to be granted from a variety of copyright owners. This is common for certain types of music with multiple writers. For commercial music, obtaining permission from one party is not that common. There may be a variety of roads one must go down before determining the appropriate rights holders. A lot of hip-hop and Top 40 songs were written through collaboration between writers and producers. Beyoncé’s “Run the World (Girl)” has 6 writers and 7 publishers, while “Power” by Kanye West boasts a ridiculous 14 writers and 8 publishers. Needless to say, when a client comes to us wishing to license one of these titles, we politely advise them against it because there are simply too many entities from which approval must be sought. Or we ask them to be patient and ditch the deadline, as it will take time and patience to get the music fully cleared.

For the Netflix original series Last Chance U we cleared the Young Thug song “Best Friend” through his lawyer. The lawyer only represented 40% of the song, but after five months of negotiation in which a license was issued and revised to suit their needs, the lawyer for Young Thug informed us that two publishers had purchased the rights, and so we had to start from scratch to secure them.

COPYRIGHT SPLITS

Splits or copyright splits involve ownership percentages. Since there can be multiple writers, there can be splits in the copyright shares. A composition’s ownership must add up to a total of 100% worldwide interest in and to a copyright. If a songwriter is part of a group of writers, it is important to confirm clearance of the entire song. Many songwriters enjoy the process of writing but may not understand, or feel comfortable, drawing a line between business and pleasure. When two musicians get together for a session and one writer says, “Hey man. It was great to play with you, let’s do this again,” hopefully they come to an agreement as to what percentage of the song each holds. If this is not sorted out, the song could be left registered to the wrong entity or with incorrect splits, and any future earnings will go to the wrong entity.

p.17

Likewise, it is essential for any person wanting to use a song that in order to incorporate the composition into a production, all the contributing writers of the song must be contacted to secure approvals. This ensures that 100% of a song is cleared for use. If there are two people who wrote a song, generally the split is 50/50. For example, Ed Sheeran’s song “Thinking Out Loud” was written by Edward Christopher Sheeran and Amy Wadge. The writers’ share is split 50/50 between the two, whereas the song “The A Team” was written solely by Ed, hence he controls 100% of this song.

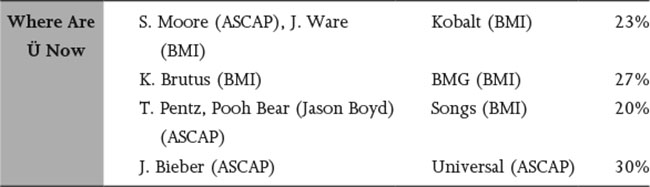

So, in this case, if you wanted to use “Thinking Out Loud” you would have to obtain permission from the two writers via their publishers, Sony/ATV and BDI. In many electronic dance tracks there are multiple writers. Take, for example, Jack Ü, the collaboration between Skrillex and Diplo, and their song “Where Are Ü Now,” featuring Justin Bieber.

Or “How Deep Is Your Love” by Calvin Harris and Disciples:

p.18

Although uncommon, one may encounter what is called a split dispute wherein the total ownership value in and to a composition adds up to less than or greater than 100%. This information is usually discovered during the clearance process, when the copyright owners tell you what their percentage shares are. Split disputes pose a challenge in that they may cause a delay in getting a piece of music clearance. The copyright owners will check with their copyright departments to check the contracts governing the music. They may reach out to each other to discuss the matter. This can all result in delays in getting the piece cleared or, worse, deem the music un-licensable until the dispute is resolved. We saw this issue when clearing the Gene Vincent song “Be-Bop-A-Lula” for a live performance. The song was cleared for $2,500. There were three copyright holders—Warner Chappell, Sony/ATV, and Music Sales—and the following ownership percentages were given at the time of the production:

As you can see, the numbers total more than the agreed fee, so the dispute was discussed and months later rectified. However, note that a dispute is not always about percentages, but can involve territories of ownership as well.

INFRINGEMENT OF COPYRIGHT

Copyright infringement occurs when someone violates the exclusive rights of the copyright owner, or, essentially, uses the song without permission. Whether or not a song is actually registered with the U.S. Copyright Office, the copyright owner’s work is protected. We have heard this question many times: “I looked up the song and it was not registered. So it’s free to use, right?” Wrong. A work is copyrighted the second it is fixed in any tangible medium. One would have to attempt to find the songwriter. Registration is not a precondition to copyright protection; it’s a formality that most importantly establishes that the certain work was in one’s possession at a specific time. Some folks like the old poor man’s copyright method. Say, for whatever reason, you do not wish to register your work. Instead, you place the song in an envelope and mail it to yourself. When it’s returned to you it has your name and a date stamp to positively prove that the work at least belonged to you as of the date on the stamp. The problem is, there is nothing in the law that acknowledges the validity or accuracy of this method. When you formerly register a song with the Copyright Office you fill out an online form, pay the registration fee, lay out your copyright, and if the registration is accepted your copyright is said to be registered. So why not do it? Registration establishes a public record of the copyright claim and makes it easier to bring a law suit against an infringer. Certain remedies are available when a work has been physically registered versus when it has not. For example, in general cases of infringement due to naïveté or ignorance, liability for civil copyright infringement involves actual damages and profits, which can be very difficult to prove. If the work has been registered, however, statutory damages range from $750 to $30,000 per work infringed, and up to $150,000 per work infringed if it can be proved that the plaintiff willfully (or knowingly) infringed. Statutory damages are awards set by the court because it cannot be determined what the copyright owners’ actual losses were or what the plaintiffs’ actual gains were. A court also has the discretion to assess costs and attorneys’ fees too, which is among the greatest inducements to registering a work.

p.19

It is important to note that each owner of each exclusive right may have a claim against an infringer. This is because any exclusive right (i.e., the right of reproduction, the right to make a derivative work or the right to publicly perform a work) may be assigned or licensed to a third party, or multiple third parties. For example, most publishers utilize the Harry Fox Agency to handle mechanical licensing on their behalf, or ASCAP, BMI and SESAC to handle public performance licensing on their behalf. The individual publisher handles everything else. So, for example, if a filmmaker released a film without securing a synchronization license and in addition released a soundtrack album containing that song without securing a mechanical license, both the publisher and Harry Fox would have separate claims as each of their exclusive rights were violated by unlicensed use.

p.20

Filmmakers always ask, “Will I get sued if I use this song?” No. Practically speaking, a filmmaker using a song that has not been cleared (or for which permission has not been obtained) for use in their production will rarely, if ever, go to court. What will occur, however, is that they will receive a lovely formal cease-and-desist letter from a lawyer which puts an infringer on notice prior to any action. This notice usually contains a demand that an action be taken (e.g., remove the music from future sales units of the film, or remove the film from a website or third-party streaming platform). Here’s an example of such a letter:

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

To Whom It May Concern,

This firm represents the recording artist professionally known as Superior Dogsleds (‘Artist’). It has come to our attention that www.operatingwithoutlicense.com (‘Website’) is currently selling and otherwise exploiting audio-visual music lessons via the Internet which embody musical compositions written and controlled by Artist (‘Compositions’).

Please be advised that our client has not granted to Website or any other individual or entity on Website’s behalf any rights whatsoever to exploit or otherwise use the Compositions. Website’s actions constitute, among other things, infringement of our client’s copyrights therein.

Based on the foregoing, we hereby demand, on behalf of our client, that you immediately remove any audio or audio-visual lesson, and other materials which embody the Compositions, from the Website (and any and all associated URLs) and cease and desist from any further exploitation or other use of the Compositions. Demand is further made that you immediately account to us for any and all revenues you have received in connection with your use of the Compositions, from the date of first exploitation until present date. We also demand that you provide us with any and all information available with respect to sales or other exploitations of the Compositions. Please notify us that you intend to comply with the foregoing demands.

p.21

If you fail to comply with the aforesaid demands within ten (10) days from the date hereof, then please be advised that our client has authorized us to take any and all action necessary or appropriate in the circumstances to vigorously enforce our client’s rights and remedies at law and equity. Without limiting the foregoing to the extent you have knowledge of the facts set forth herein and continue to exploit the Compositions, we intend to seek any and all punitive damages available as a result of your actions in bad faith in connection with this matter.

All rights reserved.

Sincerely,

Counsel for Artist

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Basically, the infringer is told to stop infringing, pay a penalty for the infringed use (based on prior exploitation of the production) or negotiate a fee to move forward and continue using the music. In our experience, which deals in the use of music in synchronization with a film or other audio-visual production, we have yet to see any copyright use of a song go to court. In film, especially in independent films, having the infringer stop (rather than pay up) is more important. The infringer would almost always be asked to correct the infringement on further distributions of the film, so that if they haven’t released it on DVD yet, they must correct the DVD. If a fee is required, it is usually established by calculating how many exhibitions of the film or project have taken place and the market value is paid. Far more sticky are the court cases involving infringements where substantial amounts of money are involved. These suits pertain to copyright infringement when an infringement involves use of music in a new, commercially released track, such as the Marvin Gaye/Robin Thicke case for “Blurred Lines,” or The Verve’s “Bittersweet Symphony,” which integrates five notes of the Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time.” In the “Blurred Lines” case, the song was tremendously popular at the time, so winning in court would be a windfall for the estate, which indeed it was.

p.22

There are also Name and Likeness cases: for example, in the Tom Waits vs. Frito-Lay case, the client Frito-Lay did not secure the rights to Mr. Waits’ recording of “Step Right Up.” Instead it found a singer who sounded exactly like Tom Waits, and used their recording of the song. Since the recording sounded so similar to the original, the client stepped on Mr. Waits’ signature vocal style and hence this was ground for infringement. Mr. Waits won the 1992 case.

Although not required by law, if there is a copyright notice on any type of work that is planned to be used in your production, pay attention and make sure to license it. There is the copyright in the composition, marked with a © symbol, and copyright for publicly distributed records, etc., with the symbol ℗. The ℗ refers to the year of the first publication of the sound recording, while © refers to the owner of the composition. Both symbols are accompanied by the names of the owners of the copyright, i.e., the songwriters (or the music publisher) and the artist (or the label).

FAIR USE DEFENSE

It has been mentioned that copyright infringement occurs whenever someone violates the exclusive rights of a copyright owner, with some limitations or exemptions. Fair use is one such exemption. Fair use is a legal doctrine that allows anyone (under Section 102 of the Copyright Act) to copy, publish, or distribute parts of a copyrighted work, without permission, in limited circumstances: as commentary, news reporting or parody or as scholarly work. Fair use is a concept that is frequently debated and frequently misunderstood. Section 107 of the Copyright Act sets out the four factors that may be used in determining whether a filmmaker may claim fair use as a defense to copyright infringement:

• purpose and character of the use;

p.23

• nature of the copyrighted work;

• amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

• effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Courts will look at the amount of material used and whether the unlicensed use ‘transforms’ or adds value to the material taken from the copyrighted work. However, the reality is that there is no black and white rule to determine whether a use is fair or qualifies as a parody.

A use is not deemed ‘fair’ until a court says it is, so guidance in this area rests heavily in case law. Content users will often license the copyright in question in order to avoid unpleasant legal consequences or litigation. But before succumbing, it is strongly recommended to seek legal counsel and obtain an opinion. There are strong advantages to seeking legal review of your film for fair-use assessment. Some are dissuaded given the cost in ‘lawyering up,’ yet it is usually a big cost saving should a review reveal that many items do not need to be licensed. Opinion letters are letters written by lawyers. They render legal opinion on whether or not certain assets used in your film could be used pursuant to fair use. They are great to have on file should you need to provide one to an insurance company as part of an errors and commissions package, or to the film distributor.

“Case law is extremely strong on the fair use points, especially in documentaries,” says Lisa Callif of Donaldson and Callif, LLP, an entertainment law firm which specializes in the representation of independent producers in film, television and web-based content.

In features there’s not as much case law going on. But still, all the people out there really support a storyteller’s right to use a limited amount of information for the purpose of comment or criticism. And whatever that may be—whether a studio film or a photograph or a piece of music—the same rules apply across the different types of intellectual property. This is why we can do what we do [write opinion letters] and insurance companies will accept them.

p.24

Donaldson and Callif work on numerous films a year. They have identified a pattern that can help filmmakers confidently determine whether the use of copyrighted material in their film could be deemed fair use; that is, if, for a non-fiction project, they can answer affirmatively to these three questions:

1. Does the asset illustrate or support a point that the creator is trying to make in the new work?

2. Does the creator of the new work use only as much of the asset as is reasonably appropriate to illustrate or support the point being made?

3. Is the connection between the point being made and the asset being used to illustrate or support the point clear to the average viewer?

Seeking the advice of counsel early on is also better from a budgetary standpoint. The cost to hire a lawyer to review your film and provide a fair-use assessment will be much less than the cost to license all the music and clips being used. Additionally, when you do not enter into a license agreement, it follows that you will not be responsible to pay reuse fees. This responsibility is passed on to filmmakers from the producers as part of the standard language contained in the license agreements. Filmmakers save money by not only avoiding payment of a license fee, but they also avoid the obligation of paying union reuse fees. Unions like the American Federation of Musicians and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists collect payments for the reuse of recordings in motion picture as if the musician who rendered services for the sound recording walked onto set and rendered services for the use of that recording in the film. These payments are charged to the licensors, who pass the obligation on to the filmmaker in their synch licenses.

Lisa Callif says,

We can help filmmakers formulate how they are going to move forward. We assess what will license and what won’t. We work with them so that the client can properly license what they need to license, and properly fair-use what they need to fair-use. When a client comes later seeking an opinion it becomes more tricky. There is still time to fair-use things but it doesn’t change the legal arguments. It can put you on the radar of that licensor and create an uncomfortable situation. This of course incurs legal fees since lawyers have to go back and negotiate things for a nominal fee through what’s sometimes referred to as a ‘fair use’ license.

p.25

FAIR USE IN ADVERTISING

When something is used pursuant to fair use in the body of a film, it does not mean that the same material could be used out of context in a promo for the film. In fact, it almost never can. Promo use raises several other issues, such as publicity rights, that are not relevant when the use of the material, for example, was circumstantial in the body of the film. Promos or trailers are seen as marketing tools. “With promos, the music is taken out of context and therefore is no longer fair use,” says Callif.

For example, our firm worked on the documentary film Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me.

In the film, some clips were used pursuant to fair use. When it came time to release a series of promo spots for the film, the team had to remove these clips because they were being used out of context. Just because something is fair game in the film does not mean it is fair game for use in a trailer. Its purpose is to advertise rather than add commentary, much like the documentary itself.

CREDITS IN FAIR USE

So if something is being used ‘fairly’ and therefore does not require a license, should one still credit the song in the end credits, or list the use in the cue sheet? A cue sheet is a log document that lists all the compositions in the body of a film or television production. It is a delivery requirement of all public broadcasters and exhibitors in order to compensate songwriters for the public performance of their music. (See Chapter 6 for a detailed look at cue sheets.)

p.26

Figure 2.4 Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me—2014

Not licensing the material is declaring that there is no need to secure a license for the use of the music in a film, but adding the music on the cue sheet would still afford the writers performance income, which is a responsibility of the broadcasting entities, not the filmmaker. Whatever position you take, or are advised to take by your lawyer, we would recommend not to credit the fair-used material in the same way the licensed material is credited. Material used pursuant to fair use has its own credit section, such as ‘Additional music’ or ‘Additional footage.’

p.27

Fair use is by no means all or nothing. If you decide to fair-use portions of your film, it doesn’t mean you won’t be doing any licensing. Many times a project includes both, and this is when a clear understanding between the production’s legal counsel and the clearance person is important. The objective is to have a fully cleared film at the end of the day, and therefore the job of the clearance person is to deliver all copyrighted materials as designated by the chosen legal counsel. Having a skilled team beside you will make the process move as smoothly and effectively as possible.

PUBLIC DOMAIN

Copyright protection does not last forever. When copyrighted works expire (dependent on what year the work was created) they fall into what is called the public domain. A work is in the public domain when no one can find any law that gives them legal claim to that property. When a piece of music is in the public domain, it is considered communal property and can be used freely without permission and in any way one can imagine. You can arrange, reproduce, perform, record or publish it, and use or sell it commercially.

A popular rule of thumb is that all works created prior to 1923 are in the public domain. Some examples are traditional, religious and classical music. As with all rules, however, there are exceptions. This general rule does not address unpublished works, extensions, and a variety of other exemptions. It also does not address arrangements of public-domain work, which may be copyrighted even if the original work falls in the public domain. A good example of this is the song “Jingle Bells,” which was originally written by James Lord Pierpont in 1857.

The original song is in the public domain. However, there are dozens of versions of “Jingle Bells,” so you need to check whether the arrangement you decide to use is copyrighted. When a public-domain song has been rearranged, the new arrangement can by copyrighted and protected under U.S. copyright law. One example is the popular Christmas rock version, “Jingle Bells Rock” by Bobby Helms. This is a fun, upbeat version of the popular tune and a standard on Christmas compilations. Or there is the Brian Setzer Orchestra’s published arranged version that replaces “one-horse open sleigh” in the first verse with “’57 Chevrolet.” Together these new lyrics and its big-band feel make the song a classic licensing favorite for special products and contemporary film scenes. This is just one example of many where it is important to do some digging when using a seemingly public-domain song in your film. If you include the song with the mistaken assumption that it is in the public domain, the copyright holder has grounds to sue, or issue a cease-and-desist, because the work you decided to use was under copyright protection. Always check whether the particular arrangement of a public-domain work that you want to incorporate into your production is copyrighted. You can do so by checking first at www.pdinfo.com or paying an outside service such as the Motion Picture Information Service (MPIS), owned and operated by Elias Savada, to do the research for you and provide documentation to back up your claim.

p.28

Figure 2.5 Public domain song “Jingle Bells”—1857

p.29

Here is an example of a public-domain search report provided by MPIS for the song “Mary, Don’t You Weep”:

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Mary, Don’t You Weep No registration and/or renewal was found for the published music of the arrangement by Inez Andrews [1929–2012] of this 1958 hit song for which she sang lead for The Caravans. The tune, alternately titled O Mary Don’t You Weep, Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep, Don’t You Mourn, and other variations is a Negro spiritual that originated from before the American Civil War. It was first recorded in 1915. A performance of the song was included on the sound recording The Remarkable Inez Andrews with the True Voices of Christ Concert Ensemble, Recorded ‘Live’ in Chicago, Illinois—SL 14591. It was registered for copyright SF-22-408 on November 21, 1980 by Savoy Records, Inc. (PO Box 279, Elizabeth NJ 07207), citing 1980 as the year of creation and November 12, 1980 as the date of publication in the United States. The 33 1/3rpm disc was distributed by Arista Records.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

THE INTERNET

The Internet has also introduced a slew of new issues because now people can make money from videos. Some rights holders may immediately request the blocking of a video that contains unlicensed copyrighted songs. Others may let it slide, either because subjectively they like the video, or because the video has received 1 million views in an hour and the rights holders will be monetizing on the back end. This means that in some cases an uploaded video featuring, for example, a kitten dancing to Katy Perry’s “Roar” will not be blocked since the video has received millions of views and the rights holders are generating money or ‘monetizing’ the video via ads that are running on the site, which is the case on YouTube.

p.30

If you do receive a notice to remove your video, here is what it may look like. Don’t panic. It’s just a notice, not a lawsuit. Address the notice and correct the matter and all will be well.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

We have received a formal DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) notice regarding allegedly infringing content hosted on your site. The specific content in question is as follows:

www.operatingwithoutlicense.com

The party making the complaint,

John Smith

The Company

111 Fair Street

Burbank, CA 91505

claims under penalty of perjury to be or represent the copyright owner of this content. Pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 512(c), we have removed access to the content in question.

www.loc.gov/copyright/title17/92chap5.html#512

If you believe that these works belong to you and that the copyright ownership claims of this party are false, you may file a DMCA counter-notification in the form described by the DMCA, asking that the content in question be reinstated. Unless we receive notice from the complaining party that a lawsuit has been filed to restrain you from posting the content, we will reinstate the content in question within 10–14 days after receiving your counter-notification (which will also be forwarded on to the party making the complaint).

In the meantime, we ask that you do not replace the content in question, or in any other way distribute it in conjunction with our services.

p.31

Please also be advised that copyright violation is strictly against our Terms and Conditions, and such offenses risk resulting in immediate disablement of your account should you not cooperate (not to mention the legal risk to you if they are true).

We also ask that if you are indeed infringing upon the copyright associated with these works that you delete them from your account immediately, and let us know once this has been done. We also ask that you delete any other infringing works not listed in this takedown notification, if they exist.

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to let us know.

Regards,

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Copyright law is extensive and multifaceted. It produces unending legal, ethical, and intellectual discourse. There are various ways that a creative and business affairs professional might consider to evaluate a piece of content. The issue keeps everyone busy—lawyers, publishers, labels, managers and, of course, music supervisors and clearance companies. In the end, artists need to be compensated in order to continue creating valuable works, and their work needs to be respected and acknowledged. In order to protect themselves from misuse they must register their works, and it is the artist’s right to withhold or extend the privilege to the use of their property. It’s important to always imagine yourself on the other side of the fence. This is key in negotiating, and once respect and mutual consideration are achieved, licensors and content users will be able to work together in greater harmony, a key component in a truly rich, creative society.