Chapter 1:

Embracing Good Design

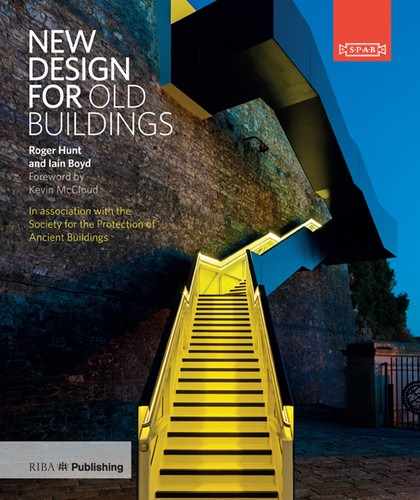

Figure 1.00

Glass‑and‑steel staircase at the Royal Academy of Arts’ Sackler Galleries

Good design is perceived, not defined. While appreciation of architectural quality is in the eye of the beholder, the origins of good design are deep, complex and subtle, particularly when related to the historic environment. There is no ‘one size fits all’ solution and it is dangerous and presumptive to prescribe a formula. But there are powerful and understood ingredients that feed dynamic, contextual and ultimately successful projects when steered by an experienced hand.

The historic built environment is frequently composed of an amalgam of accretions, eclectic styles, mixed and matched materials, varying roof lines and irregular forms that come together to create a wonderful and harmonious whole, softened by the passage of time. Contributing to this is the inevitably transformative process that results from change of use and adaptation to meet the needs of succeeding owners and occupiers. This allows buildings to live on.

Figure 1.01

The 19th‑century Granary, Barking, with a bronze‑clad extension completed in 2011

Many architects would rather start with a blank canvas, a scheme where they can express their ideas and creativity, and apply the experience of their long training. In reality, the vast majority of architects spend much of their time working with existing buildings, adapting and reinventing them through intervention and extension. The best and most successful examples retain the building’s integrity and give new life to its essential parts. Design does not stand alone; conservation and sustainability are the other vital elements that form the triumvirate of disciplines that come into play when working with old buildings. New work that is added should neither confuse the expert nor offend the casual observer. It should be possible to understand what has happened to a building over time and, when viewed, the form and detail of alterations or additions should seem both clear and harmonious.

The Nature Of Design

William Morris enjoined his clients to ‘have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’. What constitutes beauty and, by inference, good design is subjective. Writing in 1624 in The Elements of Architecture, Sir Henry Wotton interpreted the words of the first century BC Roman architect Vitruvius: ‘In Architecture, as in all other operative arts, the end must direct the operation. The end is to build well. Well building hath three conditions – commodity, firmness and delight.’

These simple words embrace both pitfalls and potential when making additions or alterations. Seeing the various phases of a building’s evolution over time is appealing and instructive. Central to the idea of readability is that new work should be of today and reflect the very best that can be achieved in terms of materials, quality and design. This approach speaks of truth and honesty rather than seeking to mimic the past – something which is often referred to derogatorily as ‘pastiche’.

Figure 1.02 Red House, Kent, designed by Philip Webb for William Morris in 1859

Pastiche is a frequently used but misunderstood word in architecture, particularly when working in the historic environment. Many architectural styles that are now highly regarded have evolved through imitation, but attempting to blatantly copy or create a pastiche of an earlier age is rarely successful and there are nearly always some concessions to modernity in the detailing and materials. More correctly, the words ‘poor pastiche’ better interpret our meaning when describing the poorly detailed, superficial and badly executed facsimiles of past architectural styles that are often seen today, both in new‑build work and extensions to old buildings.

Often the term is applied to the ‘identikit’ method of styling which sees the random application of historic elements to the exteriors and interiors of buildings in an attempt to invoke the past. These include cornices and string courses that have little regard for craftsmanship, proportion or historic precedent. One of the most commonly seen offenders is the ‘slipped’ fanlight, where a traditionally separate architectural element (the fanlight: a fan‑shaped glazed opening above the door, infilling the structural arch and providing light to the hallway) becomes instead an integral part of the front door. This represents an inept version of the original, typically Georgian, feature.

Such approaches respond to a view that new building work in historic settings should seek to replicate and match the appearance of existing structures. Skilfully done, ‘good pastiche’ may be appropriate in certain circumstances – for example, where part of a larger architectural composition has been lost – but, in general, new work should complement rather than slavishly imitate the old. New buildings do not need to look old nor ape the past in order to create a harmonious relationship with their historic surroundings and allow the primacy of older buildings to be clear.

Writing in 1892, Hugh Thackeray Turner, the SPAB’s first secretary, noted that ‘new parts should be as plain and unostentatious, though as sound and good, as possible and should clearly tell their own tale of having been erected in the nineteenth century, to harmonise with, but not to imitate, the earlier work’.

Figure 1.03

Compton Verney, Warwickshire, with a contrasting wing in stone added in 2004

Figure 1.04

Modern and Victorian gables at Gorton Monastery, Manchester.

A twenty‑first century example of this thinking is the work carried out at Compton Verney in Warwickshire by Stanton Williams alongside conservation architects Rodney Melville + Partners. The transformation of the Grade I listed mansion into a major arts venue included the construction of environmentally controlled galleries within the house and a new education centre and offices set among renovated historic outbuildings, the new extension acting as a foil to the existing house.

Figure 1.05

The barrel‑roofed extension at Binham Priory, Norfolk.

The success of such additions results from the fact that they consider the use of the building over the longer term rather than being a response to a short‑term need. Carefully executed modern design suggests honesty in execution and confidence in the architecture of today while adding a fresh layer of history to be valued by future generations.

Good Manners

‘Well‑mannered’ is the description best suited to new design that succeeds in a historic context with alterations and additions made in a form sympathetic and complementary to that which exists. These schemes have seen new work fitted to old, rather than requiring that the old be adapted to fit the new. The new structures do not compete unduly with the old building in form or position, but equally do not ape the original or pretend to be historic; instead they fulfil modern needs in a modern style. Put simply, while not necessarily ‘quiet’, they are mannerly rather than ‘rude’.

Exemplifying the well‑mannered approach is the work by Donald Insall Associates at Binham Priory in Norfolk, founded in the eleventh century. This project, completed in 1990, saw the creation of a new porch providing level access into the church for people with disabilities. Adjacent WCs for visitors to the priory ruins are within a self‑ effacing barrel‑roofed extension, inserted on the site of the ruined north aisle of the historic building. This structure is kept deliberately low to avoid obscuring the sight lines through the windows from within the church and is undoubtedly modern in its design, despite the use of flint and stone to blend new with old.

Much bolder, but still mannerly, is the work undertaken to revive the Grade II* listed Gorton Monastery (the Church and Friary of St Francis) in east Manchester. Built between 1863 and 1872 and designed by Edward Pugin, son of AWN Pugin, the building suffered the indignity of appearing on the World Monument Fund Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites after it was vacated by the Franciscan order in 1989.A major campaign to save the monastery and give it new life resulted in a scheme by Austin‑Smith:Lord, completed in 2007. This included extensions and rebuilt sections which acknowledged the overall plan and form without fighting the High Victorian Gothic architecture. The building is now functional, popular and an inspiring venue for corporate, social and cultural events.

Figure 1.06

The Investcorp Building at St Antony’s College, Oxford, abuts its neighbour

Figure 1.07

A London warehouse loading door tells a story from function to redundancy

One building that arguably falls into the ‘rude’ category is the Investcorp Building for St Antony’s College, Oxford, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects and completed in 2015. While the design is brilliant, innovative and makes good use of modern materials, the junctions with the older buildings appear ill‑considered and ignore their forms.

The Desire to Retain the Old

Old buildings and the history and character they embody engender colossal interest and support both among building professions and the public. The past understandably conjures up nostalgia, romance and fantasy. Peeling paint, the broken window and the shabby doorcase of the urban terrace are potentially just as evocative as the ivy‑clad ruin standing forlornly in the mist. As life becomes increasingly virtual, architecture’s capacity to curate meaningful, physical experiences that go beyond style is ever more important. The fabric of old buildings is not only visually appealing but retains information about how people lived, how they worked and what they valued; it also has an amazing capacity to evoke memories. The relationship between an individual building and the city, town or village in which it stands is equally important. Giving new life to old buildings has the capacity to lend rootedness and continuity to a place while also reviving economic and community wellbeing.

Valuing Change and Additions

The introduction of new design elements tends to be thought of as an additive process. In reality it is also subtractive as, through necessity, some existing elements are invariably affected. Good designers do not happily sacrifice old fabric without reason. Those involved in conservation think hard about loss and change but this does not mean that all old fabric is inevitably sacred.

Figure 1.08

Historic context and location informs the sense of place at Chiddingfold, Surrey.

A conservation approach begins from a position that historic fabric of all dates and types may hold interest, but the strength of this interest can be weighed against the long‑term benefits of change.

Widespread public awareness and interest in design has blossomed in recent years and it can be no coincidence that design perceptions have shifted with the explosive growth of image consumption. It is through images that buildings are often first experienced, be they on the web, in magazines or through television. These images are often inspirational, encouraging the notion of ‘grand designs’ and the idea that buildings can be radically changed and adapted. Potentially, this results in old buildings being damaged through lack of understanding but it also creates valuable awareness of the built environment, heritage and the potential of old buildings to have a continuing beneficial use.

What the experience of the image lacks is the visceral, haptic, physical nature of seeing and entering a real building. Becoming acquainted with a tangible structure is totally immersive, heightening the senses to the intensities of texture, light, shade, detail, colour, the patina of age and even sound and smell. Added to this may be the context of the building in terms of its sense of place, community and landscape. All of these things are essential contributory factors to the indefinable atmosphere of a building. Together they create impressions and help make memories that will be carried forward. The aesthetics of transformation must therefore respond to more than the photo opportunity. A well‑ executed design will connect with the ambience of the existing building, while not pretending to be part of the old or declaring itself self‑consciously as a new object. It is not the false distinction resulting from the relationship between the new and the old that is interesting. It is, instead, the new whole that has been created: the atmosphere rather than the bold statement, the layering of past and present.

Defining change

Change in old buildings is defined in many ways. Good examples do not necessarily shout that they are different. Instead they engage and have a relationship – which may not immediately be obvious – with the existing structure, form and materials. This can be seen in a method of repair often associated with old buildings and the SPAB: tile repairs. These have long been employed as a means of consolidating decaying masonry due to their ability to be modelled to the eroded profile of the historic fabric and because they clearly show where change to the original structure has occurred.

The technique involves laying clay plain tiles in mortar and keying them to the sound core of the stonework. AR Powys, former SPAB secretary, describes the result in his book Repair of Ancient Buildings, first published in 1929: ‘The material is very durable, the surface is plastic and can be modelled to fit adjoining stones, it is so keyed to the stone backing as to become a part of it, and the finished texture and colour are not objectionable, and “weather” pleasantly.’

Figure 1.09

A traditional SPAB tile repair – functional and clearly showing where change to the original structure has occurred.

Similar repairs can be made with stone tiles. These have the same ability to stabilise crumbling masonry and offer readability but on a stone building do not visually jump out as being different. The principle behind tile repair is developed in projects such as Astley Castle, the Landmark Trust property in Warwickshire. Here, carefully selected brick consolidates the eroded edges of the structure and acts as walling within the reconstruction.

Tile repair is merely one technique used to express SPAB ideas and there are many other ways in which repairs may be made to work aesthetically while still delineating difference. In the renovation of the church of St Paul, Elsted, West Sussex in 1951, John Macgregor, a conservation architect and the then honorary technical adviser to the SPAB, successfully used different materials and introduced design features that had no historic precedent, including a distinctive hexagonal window, to define the new work to the building, while respecting what remained of the old.

The building had closed and become derelict after a new church was built in the mid‑nineteenth century, although this too closed after a life of less than 100 years. In 1947 it became apparent that the unprotected Saxon walling of the nave was falling down. According to the SPAB’s archives, a local resident, anxious to see such important remains preserved, sought the advice of the Society. The SPAB commissioned a full report, in which ‘the great value of the Saxon masonry’ was stressed and a strong plea made for re‑roofing. As a result, Macgregor retained the surviving north wall of herringbone stonework, with two round‑arched doorways filled in to make lancet windows. The new walls are of roughly squared ashlar outside and whitewashed brick inside, with a panelled roof. Macgregor incorporated an arch of 1622 in a new south porch, west of what appears from outside to be an aisle with a clerestory above, but is in fact a vestry. Instead of a belfry, a bell is hung from the east gable of the nave; in the west gable Macgregor inserted the new hexagonal window.

Of an altogether different scale, Bracken House in the City of London was built in the second half of the 1950s to house the headquarters of the Financial Times. The architect, Sir Albert Richardson, a SPAB member and conservationist, was in the Webb tradition, drawing heavily on historical influences and yet combining them in new ways. With Bracken House he brought new design – of a traditionally inspired kind – to bear in a highly sensitive historic context. Notably, when threatened with demolition in 1987, the building received a Grade II* listing, becoming the first post‑Second World War structure to be protected in this way.

In the same year the building was sold and, with both the journalists and the printing works that it housed gone, Hopkins Architects was appointed to turn the building into modern office space. The printing works was replaced with a new block linking into the refurbished office wings and the entrance moved to the centre, its pink sandstone plinth and elliptical form allowing new build and old to merge to produce a coherent and functional new building in an important city location.

Figure 1.10

Church of St Paul, Elsted, with newer materials and design clearly distinguishable.

Figure 1.11 Bracken House, City of London, where continuity of materials enabled a shift in design.

Appreciating Historic Interest

Studying an old building’s particular architectural qualities, its construction, use and social development is enlightening. Intimacy is essential, so investing time in close‑up study beyond the desktop will almost certainly provide clues that will be useful when undertaking repairs or adding new elements. It will also help in understanding why decay sets in and how problems may be put right.

Before computer aided design (CAD), digital imaging and laser scanning, architects, surveyors and engineers came to have an affinity with, and be knowledgeable about, the structures with which they were involved because they were forced to measure and draw every detail on site. Today there is the danger that an electronic file of drawings and plans will arrive ‘cold’ on their desk and consequently they are removed from that opportunity to understand the idiosyncrasies, details and atmosphere of the building with which they will be working.

Figure 1.12

Grooves worn into the fabric of a church tower by decades of bell ringers’ ropes – a detail that can be missed by electronic methods of assessing a building.

Clearly the accuracy and time savings provided by modern techniques are to be welcomed but it is important not to disregard the value of close‑up, on‑site understanding. A CAD survey will not, for example, pick up a season joint in brickwork where the original builders stopped work for the winter and, having capped the wall off to stop rain and frost penetration, had then not scraped mortar away before continuing the following season. This ‘tidemark’ may not have any practical value but it is an intrinsic part of the building’s history and aesthetic.

Long-Term Thinking

Many buildings have remained unchanged for hundreds of years, partly because the demands placed on them have altered little and their fabric has been uncomplicated and simple to maintain. The speed of change is quicker today than ever before and it is easy to look at the immediate gain of adding new technology or embarking on adaptation and change without considering the validity of interventions in the longer term.

Figure 1.13

Lifting this historic church floor for underfloor heating would cause irreparable harm.

Work to buildings that will have only a relatively short‑term benefit or will, by its nature, not be long‑lasting is unlikely to be either sustainable or sympathetic to the fabric of the building. Inevitably, in the future, attempts will be made to reverse or modify changes and there will be a need to replace systems or components when they reach the end of their life. These ongoing interventions may, when judged against the future life of the building, happen over a relatively short period of time and, on each occasion, will invariably result in further loss of the structure’s fabric and character.

One example of this process is underfloor heating, which is increasingly being considered in churches and houses. There are good reasons for its use: underfloor heating is seen as a sustainable and efficient solution that can reduce energy consumption, especially if used with renewable energy sources. Unfortunately, its installation in old buildings is likely to involve major upheaval and may have a significant impact on existing floor finishes and archaeology, while potentially changing the building’s natural equilibrium when it comes to moisture control. In addition, these systems have a limited lifespan which may represent only a single generation. This might mean that the heating pipes have to be dug up and replaced, with all the inherent damage and loss that may result.

Similarly, the replacement or adaptation of centuries‑old windows to accommodate double glazing aimed at improving thermal performance can be short‑sighted when the average guarantee on the new unit is just ten years. Another controversial area is the substitution of leadwork with modern materials such as fibreglass which, while cheaper and less prone to theft, is a short‑term solution and results in the loss of craft skills. Clearly, with any work, thought must be given to avoid potential opportunities being lost, while having consideration for the past and the future, as well as the present. A 200‑year‑old building may, after all, stand for another 200 years, and any work that compromises or does not take this possibility into account is almost certainly misguided.

Place and Community

Figure 1.14

Timber‑frame upper ranges set over older stone walls in Winchester, Hampshire.

Individually and in groups, old buildings contribute richness and variety, helping to create places and communities. An awareness of the historic circumstance of their surroundings is essential: the traditional village green is as much about the buildings that surround it as the open space at its heart. Vernacular buildings in particular are products of local wisdom, climate and tradition. They are strongly related to the geography and history of a place, the lie of the land and the pattern of other development. Their styles reflect the materials found in the local landscape with the result that towns and villages may be categorised as being timber, brick or stone, thus contributing immensely to the sense of place and making them inseparable from the setting where they are found.

Retaining buildings in their setting enriches the character of an area and is essential to understanding the building’s construction and the origins of its materials, craftsmanship and use. Conversely, integrity is undermined by dismantling and re‑erecting these buildings in another location. Historic fabric is likely to be destroyed when a building is moved and the context is lost. All of this is important when considering new design and inevitably the approach will vary in every case. Should the response be to echo the existing material or should it consciously challenge the status quo, perhaps by introducing a new finish, material or colour?

In Littlehampton, West Sussex, Heatherwick Studio’s East Beach Café, completed in 2007, may appear radical and a direct challenge to everything in its surroundings. In fact, it is a refreshing counterpoint to the Victorian seafront terraces and a welcome alternative to what could have been. According to the café’s website: ‘Before East Beach Café, there was a tiny kiosk on the site serving burgers, chips and nuggets. The owner got permission to turn it into a big restaurant, but the building he planned was not a pretty sight. Great for serving lots more chips and nuggets, but not of any architectural merit.’

Figure 1.15 East Beach Café, Littlehampton, a popular design and a contrast to the Victorian seafront.

East Beach Café passed the planning process without a single objection, although such an approach may prove less acceptable in environments of close‑knit historic buildings. Quite rightly, the criteria will subtly change tosuit specific surroundings, but this is not to say that something fresh and responsive to the context would be out of place, provided it is well‑mannered in form, function and proportion.

Regeneration

Regeneration of places in decline, through conservation combined with good new design, has been proven to work, reaping rewards for the economy of the local area and for the character and quality of the local environment. Even comparatively small projects bring benefits. East Beach Cafe gives a new reason to visit Littlehampton and brings new life to the resort. Local car park revenues are up 87 per cent, the town has new supermarkets and the café’s owners are passionate about the power of business and design to change environments.

The creative re‑use of old buildings can act as a catalyst to the process of regeneration, with successful schemes harnessing history, stitching together communities and drawing outsiders in. Urban Splash is a company that has been at the forefront of regeneration since the early 1990s with old, often listed, buildings at the heart of many of its schemes. Typically, these schemes are mixed use – involving residential accomodation, office space and leisure facilities – encouraging people to come in, see and use them. Often this involves making a new place, whether it is reinventing the historic Royal William Yard in Plymouth, Devon, the Rope Walks in Liverpool, the Lister Mills near Bradford or the 1930s Midland Hotel, Morecambe, which became a potent symbol of renaissance for the seaside town. In each case the focus has been as much on place‑making as the individual buildings.

With the Grade I listed Royal William Yard the real challenge was not so much the buildings themselves – although there were inevitably challenges over cost and conservation – but the location. The development was on the ‘wrong side’ of Plymouth and, having historically been a victualling yard, there were perceptions about the surroundings, for example a red light district once existed nearby. For the scheme to succeed, the overall design quality had to be sufficiently high to bring in really good restaurateurs, businesses, residents and visitors to enjoy and use the buildings.

Good design has always been a vital ingredient for Urban Splash. Grade II* listed Park Hill, a former council housing block, is a landmark on the Sheffield skyline immediately to the east of the mainline railway station and city centre.

When it opened in 1961 it was the most ambitious inner‑city development of its time but by the 1980s the area was so run down and the perceptions so poor that it was on

the brink of demolition. For the regeneration to succeed it was necessary, in this case, for Urban Splash to take a radical approach. This included losing much of the original interior to create a place for nearly 2,000 people to live, with offices, shops, a nursery, bars and restaurants below. The bold design strategy of architects HawkinsBrown, working with Studio Egret West, transformed the modernist concrete landmark through the creation of new openings, the introduction of daylight and the use of colour.

Figure 1.16 Assertive design by Urban Splash at Royal William Yard, in Plymouth, working with and around the historic walls.

In Bolton, Greater Manchester, the Churches Conservation Trust and OMI architects worked with local community leaders to transform the outstanding but unused Grade II* listed All Souls Church for the benefit of all who live and work locally. Standing at the heart of a multifaith community, the Victorian building reopened in December 2014 as a place for social enterprise. It welcomes all who venture through the door, including individuals who enjoy the café and activities, and local businesses who rent the facilities in the pods created inside the church for meetings and events.

Projects defined by good design, such as All Souls Bolton, have the potential to be hugely socially rewarding when undertaken in less affluent areas that suffer the additional challenge of aesthetic poverty in terms of modern design. Unless the motivation is strong, money to fund these projects and the political will to see them through is frequently diverted to focus on more direct needs, but by offering beacons of aspiration based on great new design the impact can be immense when a building is given a new future at the centre of a community. Embedding outreach, education and training from day one of such projects is essential. In the long term the building must be self‑sustaining and capable of existing without subsidy.

>Figure 1.17 Pods and a café within All Souls Bolton.

Designing places

Good design in the historic environment involves maintaining interest, scale and a relationship with the buildings at its heart, while the spaces between and around the buildings provide their setting. The materials employed in these spaces often reflect the local vernacular and reveal patterns of wear and age while, below the surface, there may be a rich layer of archaeology.

Within the setting, the makeup of old paths, roads, hedges, walls and even signage creates context and interest, but appearance is not the only consideration: cobbles, for example, create a very different soundscape to gravel so a change in surface treatment can drastically affect the ambience of a place. Any new scheme must take these factors into account to ensure local character is strengthened rather than diminished and, just as with old buildings, a philosophy of repair, care and good new design is essential.

Although generally welcomed, traffic calming and pedestrianisation schemes need considerable thought as some alteration to the surfaces and spaces between buildings is inevitable. Appropriate selection of materials and layout is key. Block paving, for instance, can create sterile areas and a full carpet of identical wall‑to‑wall paving should also be avoided. Well‑designed street furniture is important, as is the avoidance of unnecessary clutter caused by signage, bollards, planters and bins

Figure 1.18

Streetscape in London’s Inner Temple, deriving character from cobbles and paving.

Materials and Craft Skills

Figure 1.19

Handmade bricks provide a direct connection with the maker.

The word ‘craft’ has the same meaning today as it did to William Morris. He sought simplicity and truth in a well‑made thing: beautifully crafted buildings are at their best when they are uncomplicated and bear the mark of their maker. Craftsmanship sometimes seems expensive but it delivers pleasure in the long term. Match craftsmanship with high‑quality, carefully selected materials and the building becomes distinct. Add to this good design and it is possible not only to embrace the here and now but to create a dialogue with the existing building and its context that reaches back through history.

A Georgian facade is not simply about proportion but also the beauty that springs from its subtlety and detail, brought alive by the craftsmanship of the bricklayer, joiner and mason. Imperfections are part of this; each glazing bar is uniquely formed, every pane of glass unintentionally distorted. We feel connected to the maker when we see a thumbprint in the clay of a brick or tile, the saw marks on a piece of timber, or the trowelling on an expanse of plaster.

Conservation Through Design

Good design goes far beyond aesthetics. In many cases design innovation is vital to the conservation of old buildings due to the engineering solutions that it can offer, frequently in conjunction with new materials and technology. The use of these methods allows the integrity of the building to be maintained and as much historic fabric as possible to be retained while providing an honest approach that is easily readable in the future.

Figure 1.20

A thoughtfully designed engineering intervention to support 800‑year‑old timber at Headstone Manor, Harrow.

Headstone Manor in Harrow, west London, shows that the solution is often an architectural as well as engineering one. Here, the oldest part of the existing building is a very early timber frame of around 1310 in a surviving portion of the great hall. Its extreme fragility meant carpentry repairs would have created a huge loss of fabric and been quite destructive. The solution, devised by architect Francis Maude, a SPAB Scholar working at Donald Insall Associates, retains as much of the original fabric as possible.

Horizontal steel beams, which project beyond the building, were inserted beneath the wall plates and to these were attached steel uprights outside. This created a clearly expressed modern steel frame which holds the historic timber frame of the building in place. While initially quite startling, it is a good solution in conservation terms which has ensured that the building remains viable and succeeds in its new role as part of the Harrow Museum. The metalwork could have been entirely functional, but is thoughtfully designed where it projects from the building’s exterior.

Diverse Styles and Approaches

The Firs, in Redhill Surrey, is what Nikolaus Pevsner, in The Buildings of England series, describes as ‘a suave Regency-style house.’ What distinguishes it is the uncompromisingly modern wing, approximately the size of the older house, added by Basil Ward of Connell, Ward & Lucas in 1936. As Pevsner notes, this is a very early and very brave case of not ‘keeping in keeping’. He goes on to describe it as a ‘perfect counterpoint between old and new, for example in the very careful but not servile relation of roof-lines, and the graded recession from the old to the new via the stair-well’.

Very different, but nonetheless effective, was the approach taken by the architects Seely and Paget for Stephen and Virginia Courtauld at Eltham Palace in 1933–6. Here the new butterfly‑plan house, with wings of red brick with Clipsham stone dressings, incorporated the medieval great hall, in the process adding layers of interest to what had been a ruin.

These were among the forerunners of the countless schemes that now exemplify the qualities of good new design within the historic environment. Some responses are bold and have fun with the new work, others are restrained and self‑effacing; all can work equally well. The common theme is the need for a carefully considered relationship with the old building that is reflected in the composition, juxtaposition and huge investment in detailing of the elements that make the whole.

John Betjeman, Poet Laureate and SPAB committee member, humanised such thinking in a letter written to the architect of the National Theatre, Sir Denys Lasdun, in 1973 when the building was still unfinished: ‘I gasped with delight at the cube of your theatre in the pale blue sky and a glimpse of St Paul’s to the south of it. It is a lovely work and so good from so many angles.’

The National Theatre is now an old and listed building in its own right and has itself been the subject of recent new work that demonstrates the power of good new design in the historic context. Be it the National Theatre or the renovation and reconfiguration of 25 Tanners Hill, Deptford, a timber‑ framed house by Dow Jones Architects; the ‘eco‑pods’ inserted into the field barns of the Yorkshire Dales by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios; Haworth Tompkins’ vibrant Egg Theatre, created within the skin of a Grade II listed building in Bath; or the clever and subtle Refectory at Norwich Cathedral by Hopkins Architects, there is a common theme of creating innovative and interesting spaces that sit within and beside historic fabric without diminishing the context, values and narrative of the place.

Exceptional projects such as these are often described as exemplars but there is a danger in simply transplanting ideas from project to project. In reality, each scheme is different and requires a bespoke solution that respects and responds to the nature of the place and the individual building. There are no shortcuts to success; physically researching each building not only generates an essential understanding of its construction, materials and quirks, but also recognition that those now charged with its care will be similarly judged by generations to come.

Figure 1.21

Pevsner applauded the contrast between the new and the old at The Firs, Redhill.

Figure 1.22

The Norwich Cathedral Refectory, completed in 2004.