11 Producing the Space of Democracy

Spatial Practices and Representations of Urban Space in Spain’s Transition to Democracy

Introduction

Curiously, space is a stranger to customary political reflection. Political thought and the representations which it elaborates remain ‘up in the air’, with only an abstract relation with the soil and even the national territory… . Space belongs to the geographers in the academic division of labour. But then it reintroduces itself subversively through the effects of peripheries, the margins, the regions, the villages and local communities long abandoned, neglected, even abased through centralizing state-power.

(Lefebvre, 1976–1978: 164)

The above citation is taken from Henri Lefebvre’s work on The State (De l’Étate). It reflects the importance of spatial analysis to any discussion on the formation and consolidation of power relations within modern societies. At the time in which Lefebvre wrote these words they also reflected a difficulty to engage with space as a meaningful analytical category within most disciplines. As this volume well demonstrates, the ideas of Henri Lefebvre are currently experiencing a revival in the fields of urban studies, political geography, cultural and organizational studies (Brenner and Elden, 2009; Brenner, Marcuse, and Mayer, 2012; Elden, 2004; Purcell, 2002). In the field of history, space, while often referred to, is still looked upon more as a container of social relations than as an element that constitutes and is being constituted by them. This is despite the fact that Lefebvre’s work offers a productive platform for integrating spatial and historical analysis, not only within the field of urban history, but also for a more general analysis of the constitution of power relations and of varied forms of social resistance.

My own work in recent years focuses on the relationship between urbanization and democratization in Spain during the period of General Francisco Franco’s dictatorship (1939–1975) and Spain’s transition to democracy (1975–1982). Throughout its existence, this ultranationalist dictatorship embraced urban space as a focal point of accelerated economic growth and instituted a policy that drew industry, services and capital into the city. With the same intensity, however, it also laboured to distance the Spanish working class from the centre of most Spanish cities. The regime’s policies in terms of political repression and of urban planning can be understood only by paying careful attention to this simultaneous drive for industrialization and spatial segregation.

The current chapter examines the urban planning regimes, spatial practises and representations of urban space that emerged throughout the periphery of the city of Madrid during the final years of the dictatorship and the transition to democracy. Focusing on the formation and transformation of Orcasitas (one of Spain’s largest squatters’ settlements) I explore the interplay between spatial segregation and domination and between informality and resistance. I do so using several types of primary sources. The most important of these is a database containing information about 1,680 of the families that settled in the three barrios which made up Orcasitas between the years 1940–1965. I constructed the database drawing on files that were compiled by the Francoist Ministry of Housing between the years 1957–1966. The files document the legal and socio-economic status of the families who settled in Orcasitas and contain details concerning their origin; household composition; employment conditions; plans of the self-constructed homes (chabolas) and the legal standing of the property. The database is supplemented by a series of 34 in-depth interviews with members of the Orcasitas neighbourhood association and with individuals (7 women and 27 men) who settled in the barrios during the 1960s and 1970s either as children or as young adults. Further information is derived from urban plans, written texts and visual materials collected from the archives of the National Institute of Housing and from private collections and publications of architects and planners such as Pedro Bidagor, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza and Fernando de Terán.

In analysing the processes which led to the formation and transformation of massive squatter settlements throughout Spain, Henri Lefebvre’s prolific theory provided me with several key concepts. Of primary importance was Lefebvre’s three-dimensional model for the analysis of produced space. Lefebvre pointed to three levels on which spatial change takes place: the level of spatial practises (which assign the functions of production and of reproduction to particular locations with specific spatial characteristics); the level of representations of space (that “order” and legitimize the allocation of space and the construction of spatial practises through academic and/or professional discourses); and the level of representational or lived space (that embodies the complex symbolism of its users) (Lefebvre, 1996: 33–34). As some researchers correctly noted, this triad is not neatly drawn and much confusion exists, especially between the category of representational space and the first two categories (Shields, 1999: 161). However, the confusion, as Stuart Elden reminds us, results from Lefebvre’s dialectic method (Elden, 2004: 190). If one accepts the fact that Lefebvre intentionally introduced a third term (that of lived space) which is balanced between two poles (those of conceived and perceived space) one can better understand the production of lived space as embodying new uses alongside subjective interpretations of existing representations and practises.

The above triad highlights the role of spatial practises and of spatial representations in the production of space as we know and experience it. It further encourages us to explore the struggle over space—as both a symbolic and a material resource—by looking at the ways in which competing spatial practises and discourses establish themselves. Lefebvre was less mindful, however, of the possibility that contradictions might also exist between the spatial practises and representations produced by the same stakeholder. As I show, such contradictions may surface even when the aforementioned stakeholder is a dictatorial regime looking to implement and monitor a highly structured urban planning regime.

The first period with which the chapter is concerned constitutes an example of the unfolding of what Lefebvre termed as the second critical phase in urban development. According to Lefebvre, the first critical phase in human development encompassed a period during which agricultural society was progressively subordinated by industrialization (in the European case roughly spanning the 16th century). The second critical phase, on the other hand, is characterized by the subordination of industrialized society to an all-encompassing process of urbanization. The spatial manifestation of this phase is the emergence of a critical zone in which “industrialisation, the dominant power and a limiting factor, becomes a dominant reality during a period of profound crisis” (Lefebvre, 2003b: 16).

While some view the emergence of a “critical zone” as reflecting a future reality (Elden, 2004: 137) Lefebvre himself was rather specific in describing its attributes. The critical zone is characterized by accelerated processes of implosion—explosion which lead to a process of urban concentration and extension. This process is reflected, amongst other things, in an extensive rural exodus and the subordination of the agrarian to the urban. According to Lefebvre the result of this situation is a tremendous confusion “during which the past and the possible, the best and the worst, become intertwined” (2003b: 16). My contention is that during the first period under study here the attributes of Lefebvre’s “critical zone” manifested themselves most acutely in Spain. During this period grave contradictions surfaced between the regime’s ideological perceptions and spatial representations (according to which the urban working classes constituted a threat to political stability and therefore had to be kept away from Spain’s urban centres and channelled into well contained satellite suburbs) and its spatial practises (which strove to increase industrial output and linked the new industrial complexes to existing zones of urban concentration). Such contradictions led the dictatorship to temporarily turn a blind eye to the outpouring of working class populations into urban spaces that were not designated for their use.

The second period with which the chapter is concerned points to the circumstances under which the conditions characterizing the critical zone can nonetheless lead to a process of urban transformation: a transformation which puts the “practises of inhabitance” at the centre of the planning process. In his essay The Right to the City Henri Lefebvre referred to the concept of “inhabitance” as reflecting a creative use of space oriented towards its appropriation (Lefebvre in Kofman and Lebas, 1996: 158). Mark Purcell further elaborated on how the Lefebvrian concept of inhabitance might serve as a basis for a new citizenship regime: egalitarian decentralized and rooted in the experience of effectively inhabiting urban space (Purcell, 2003: 564). Following Purcell I use the term “practises of inhabitance” in order to highlight the accumulative effect of everyday engagement with lived space. However, I would like to emphasize the contingent nature of such practises: their goal might be to modify specific aspects of space in order to change specific elements in the experience of inhabiting without necessarily having a larger transformative project in mid.

Against this background, the first section of the chapter briefly explores the existing literature on urban segregation in the context of Lefebvre’s analysis of spatial domination. It then goes on to examine the practises that emerged in relation to the urban during the Franco dictatorship: spatial segregation (in both political and class terms) based on functional zoning and the creation of urban peripheries. I show how these practises were legitimized through corresponding references to space as hierarchical and organic in nature, as well as produced by technical knowledge. I ask how was the concept of segregation employed during a period of maximal urban concentration and expansion and what is the nature of the relationship between spatial segregation and domination?

The second section briefly examines the existing literature on the informal production of space, while relating it to Lefebvre’s scalar analysis of space and to his theory on spatial appropriation. The section then explores the production of informal space on the southern periphery of the city of Madrid between the mid 1950s and the late 1970s. Special attention is paid to the experiences of inhabiting as I reflect on the ways in which these experiences assist the users of space to apprehend and produce new knowledge regarding their lived environment. My argument in this section is that the act of squatting both complemented and challenged the regime’s spatial practises. It complemented such practises by offering the most basic housing solutions to large working class populations on lands that were situated close to the capital’s industrial complexes, thereby supporting the process of urbanization in the service of industrial expansion. At the same time, the reality of mass squatting during the final years of the dictatorship led the inhabitants, urban planning professionals and even the Spanish legal system to critically reconsider the rationale behind the allocation of resources and the existing system of urban development. The section analyses the experiences of informality that emerged out of the reality of the critical zone and asks under what conditions they can serve as the basis for the production of new urban knowledge?

Finally, the last section focuses on the ways in which informal knowledge can become the basis of new policies. Using examples from the Remodelling Plan of Orcasitas (the most radical and participatory of all remodelling plans in the capital) and from the Neighbourhoods’ General Remodelling Plan (which affected 29 sectors in the capital) I ask how can such knowledge contribute towards the modification of existing representations and practises of spatial segregation? Pointing to the extant and limitations of change my conclusions revisit Lefebvre’s notion of “right to the city” and explore the conditions under which claiming such a right is made possible.

Social Control Through Spatial Segregation: Urban Space and the Franco Regime

What is the relationship between spatial segregation and the concept of domination? Segregation is an ambiguous term (Brun and Rhein, 1994; Grafmayer, 1994; Lehman-Frisch, 2011; Leloup, 1999). It denotes the unequal distribution of social or economic groups in urban space. As such it is generally considered a negative process by urban policy makers mostly because it impedes social integration and social cohesion processes, and does not create equal opportunities in relation to education and to people’s access to the labour market. But segregation as defined by the Chicago School is also a process which refers to the tendency of “similar” people to aggregate in space (Park, 1926). In other words, segregation can be viewed as a selective process which separates different social groups, but it can also be viewed as a defensive process that provides deprived population with locally based social and symbolic resources (de Souza Briggs, 2005; Lehman-Frisch, 2011).

In the context of Henri Lefebvre’s work the meaning of spatial segregation is directly tied to the understanding of urban space itself. According to Lefebvre, the urban is a product of industrial and capital accumulation. A space dominated and transformed by modern technology which introduces onto it new forms of use, closing, sterilizing and emptying it in the process (Lefebvre, 1996: 165). But space should also be viewed as a work (oeuvre) produced by different (and at times contradicting) processes of inhabiting. Within this context spatial segregation refers to a two-fold process: market driven processes accentuate social divisions within urban space and allocate marginalized groups into urban peripheries. This process of allocation, in its turn, has the potential of denying the same populations the right to participate in the collective creation of the urban itself (Lefebvre, 1996: 195; Hoskyns, 2014: 74–75). However, the move from spatial segregation to spatial alienation is not an automatic one. It is only when segregation is used in the service of domination that it leads to alienation, that is, to the production of space in a manner contrary to the needs of the inhabitants.

The development of the metropolitan area of Madrid under the Franco regime presents an example of acute spatial segregation at the service of domination. Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, the metropolitan area of Madrid clearly embodied the characteristics of Lefebvre’s critical zone: in 1940 (immediately following the Spanish Civil War) the capital’s population stood at 1,326,647. This number doubled itself by 1960 following massive waves of internal migration from Castilla la Mancha, Extremadura and Andalucía. The ascendancy of metropolitan regions such Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Bilbao was accompanied by a corresponding “emptying out” of the Spanish countryside from both population and essential services in the fields of medicine, education, culture and commerce (Capel Sáez, 1962; Higueras Arnal, 1967; Siguán, 1959). This process was further accelerated by the annexation of “dead” rural territories into the urban. The General Plan of the City of Madrid that was published in 1941, for example, increased the capital’s size by about 20%, annexing to its outer perimeter a series of half destroyed villages and small towns such as Villaverde, Orcasitas, Vallecas etc. (Sambricio, 2004).

Under the dictatorship the production of the urban was intended to maintain a strict separation between the functions of production and reproduction. The General Plan of the City of Madrid split the capital into three concentric circles and five zones, each with a distinct function. The first circle included the historical centre of the capital. This space comprised a mixture of small residential and commercial zones but was dedicated for the most part to national monuments and administrative spaces (Box Varela, 2008: 353–437). The second circle (extrarradio), bordering on the historical centre of the city, included residential zones built mostly during the last decades of the 19th century as well as additional commercial zones. Finally, the outer circle (that in 1941 was mostly made up of undeveloped land and half destroyed villages) was to be dedicated to residential and industrial uses (Ofer, 2017: 19–38).

The residential nuclei within the outer circle were called Satellite Suburbs, a term that pointed to their ambivalent relationship with the city. The neighbourhoods of the extrarradio were connected to the historical centre of Madrid via a series of roads. The Satellite Suburbs, on the other hand, were isolated both from the centre and from each other. According to the Pedro Bidagor (the initiator of the Madrid General Plan and the person in charge of its execution) Satellite Suburbs were supposed to exist as self-sufficient units. It was never made clear how this was to happen, since none of the neighbourhoods was designed so as to include commercial spaces or basic health or education services.

Following the Civil War the Spanish General Plans relied heavily on the concept of functional zoning. In accordance with the Athens Charter that was published in 1933, functional zoning assigned specific spaces to each of the four defined functions of the modern city: Living, working, recreation and circulation (Le Corbusier, 1973). This highly rational planning module was aimed at maximizing the use of space and reducing to a minimum the cost of urbanization. Abelardo Martínez de Lamadrid, an industrial engineer who worked alongside Pedro Bidagor on the formulation of the Madrid General Plan, reflected on the social and economic function of zoning in the Spanish case:

The division into zones went hand in hand with the accepted planning criteria of the time: facilitating the access of primary material; enabling the distribution of products; and minimizing the inconveniences of industrial production. But zoning also facilitates the location of a mass population of workers in Satellite Suburbs—spatially independent of the city itself and with easy access to the countryside. In this way the green zones and industrial zones provided a bulwark against the invasion of the masses.

(Terán, 1982: 173)

As can be understood from this citation, in Spain functional zoning had two central goals: to facilitate the needs of industry and to ensure social segregation. Workers, essential as they were to the process of production, had to be excluded from the heart of the city. Francoist cities of the 1940s and early 1950s clearly embodied what Henri Lefebvre defined as the central paradox of the spatial practises under late capitalism: an association that “includes the most extreme separation between the places it links together” (Lefebvre, 1996: 38).

The architectural form of satellite suburbs reinforced the concept of hierarchical planning and the tendency to evaluate built form through the lens of exchange value. These were dormitory suburbs that could not develop a differentiated character since they lacked spaces for socialization in which communal bonds could emerge. They met what Lefebvre defined as the lowest possible threshold of sociability, “beyond which survival would be impossible because all social life would disappear” (Lefebvre, 1996: 316). Luis Larrondo Bilbao described the sense of alienation surrounding these suburbs:

An utter sense of failure became apparent and with it the understanding that the users themselves preferred a more traditional system of construction and felt uneasy in these homes… . A group of psychologists and sociologists that were contracted in order to look into the subject came to the following conclusions:

For the architect these [suburbs] symbolized the death of his creation at the hands of machinery; construction workers were weighed down by the inhuman impact of mass construction; finally, the users felt that they could not impact or reform their own home and were therefore unable to feel as if they owned it in the full sense of the word.

(Bilbao Larrondo, 2006: 258)

Under the Franco regime, the Spanish general plans strove to design not only a segregated city, but also what sociologist Richard Sennett defined as a ‘closed city’. Not only were they characterized by over determination of densities and of functions, they also aimed to create an integrated spatial system, where every part had a specific place within the overall design. Under such conditions structures that did not fit the overall design were either eliminated or acquired a diminished value and a relegated to the periphery (Sennet, 2006). The ways in which the general plans were implemented generated extraordinary imbalances during the first two decades of the dictatorship’s existence. Such imbalances were noted most of all in relation to the housing market and to the construction of infrastructures.

The Experience of Inhabiting: Producing Informal Space in the Periphery of Madrid

Despite harsh political and social repression, spatial domination in Francoist Spain was never complete. It was met with different forms of resistance: from sporadic illegal construction to more extensive alternatives which could be characterized as informal urbanism. Ananya Roy defined informal urbanism as a mode of urbanization with “an organizing logic, a system of norms that governs the process of urban transformation itself” (Roy, 2005: 148). Not all manifestations of illegal construction, therefore, can be characterized as informal urbanism. The latter term implies, in my view, a certain degree of permanence. From the researcher’s point of view the analysis of different forms of informal urbanism requires an understanding that self-constructed spaces are not shaped solely by the harsh economic conditions under which they are produced. These spaces reflect the values and the material needs of their users and therefore may hold important lessons also for those engaged in formal planning.

Architect José Castillo further defined the informal in reference to three characteristics:

First, it incorporates the notion of the casual; second, it refers to the condition of lacking precise form; and finally, it relates to the realm outside what is prescribed.

I use the term urbanisms of the informal to explain the practises (social, economic, architectural and urban) and the forms (physical and spatial) that a group of stake holders (dwellers, developers, planers, landowners and the state) undertake not only to obtain access to land and housing, but also to satisfy their need to engage in urban life.

(Brillembourg, 2006)

Catells and Portes focused on the contextual aspects of informality, emphasizing that “the informal economy does not result from the intrinsic characteristics of activities, but from the social definition of state intervention, the boundaries of the informal … will substantially vary in different contexts and historical circumstances” (Castells and Portes, 1989: 32). Research into forms of informal urban settlement in both the global south and the global north all emphasize the precarious nature of such settlements as a condition that facilitates community activism (Anders and Sedlmaier, 2017; Mayer, 2012). In this context, the concept of “appropriation,” as defined by Lefebvre, proves extremely useful. Lefebvre did not view spatial proximity in itself as a guarantee for the creation of social bonds. Rather he tried to theorize the ways in which inhabiting space reinforce collective identifications and communal activism. In L’Urbanisme aujourd’hui, he wrote:

For an individual, for a group, to inhabit is to appropriate something. Not in the sense of possessing it, but as making it an oeuvre, making it one’s own, marking it, modelling it, shaping it… . To inhabit is to appropriate space, in the midst of constraints, that is to say, to be in a conflict—often acute—between the constraining powers and the forces of appropriation.

(Lefebvre in Stanek, 2011: 87)

In The Production of Space, Lefebvre noted the appropriative potential of squatter communities but did not discuss the strategies through which squatting could in fact lead to the creation of spaces truly appropriated by their users. My contention is that under specific conditions the very nature of squatting (the context of illegality, the lack of pre-existing infrastructures, the practises of self-construction) may facilitate a more critical and purposeful engagement of people with their lived space. In order to understand under what conditions such a process may take place it is useful to consider the relationship between appropriation and spatial scales. Lefebvre proposed three scales for the analysis of space: A “private” realm, an interim level and a global level. He noted that even in the best of circumstances—when the indoor space of family life is truly appropriated by its users—the outer spaces of a community life are still mostly dominated (Lefebvre, 2003b: 86–90).

Focusing on the case of Orcasitas, I wish to point to some ways in which squatting (as an on going daily practise) can indeed lead to the appropriation of space, at both the private to the intermediate levels. This process, in its turn, can bring about the creation of communitarian “counter-spaces”: spaces that are designated a specific function but through varied uses are invested with additional functions and meanings. These counter-spaces (a water fountain which functions as the community’s meeting place and “billboard”; a barber’s shop turned into the headquarters of a neighbourhood association etc.) are locations where new subjectivities and new forms of knowledge regarding the nature of inhabitance are produced.

What is known today as the barrio of Orcasitas was originally made up of three different neighbourhoods: Meseta de Orcasitas, OrcaSur and Poblado Dirigido de Orcasitas. The first two formed between 1955 and 1962 as a result of illegal self-construction. The patterns of squatting and of community life in Orcasitas were representative of hundreds of other squatters’ settlements all over Spain. The uniqueness of Orcasitas lies in the way in which its dwellers struggled against eviction and challenged legal notions of entitlement already under the dictatorship. By forcing the local authorities to acknowledge their claim to the land they had occupied, and their status as a community of neighbours the inhabitants set a legal precedent. They also established their right to take an active part in any process of urban renovation pertaining to their barrio.

Chabolismo or barraquismo is a form of informal construction, which started to manifest itself around the periphery of Spanish cities in the 1920s. By the mid-1940s, however, squatting changed its face in Spain. From individual constructions that were scattered throughout the peripheries of large cities, it matured into dense areas covered by mass self-constructions. In Orcasitas alone 10,000 households lived in self-constructed homes by the late 1960s. A working paper composed in 1977 by the Commission for Planning and Coordination of the Madrid Metropolitan Area, stated:

With the passing of time the word chabolisimo came to signify any type of housing that was built bypassing the official procedures of urban planning… . Initially, however, chabolismo was simply an ad hoc way in which migrants and newly formed households responded to the unsolvable housing problem.

(COPLACO, 1977: 10, the author’s translation)

Constructing a chabola was clearly more difficult than renting a shared apartment in an established working class neighbourhood. Rented apartments in the centre of Madrid enjoyed better infrastructures, transportation and educational services and shopping facilities. Why, then, did so many migrant families opt for these self-constructed barrios? Barrios chabolistas provided their inhabitants with two marked advantages in comparison to other forms of dwelling: In cities with fast growing industries the squatters’ settlements were constructed in relative proximity to the new industrial complexes that provided work for many migrants. For a population deprived of any means of transportation, however, the proximity of home and work proved a marked advantage.

The chabolas as housing units also offered independence and flexibility. The uncertain status of the land enabled the inhabitants to use the perimeter surrounding their home in order to supplement their meagre earnings. The ability to grow vegetables and wheat and to raise farm animals was an advantage not found in established working class neighbourhoods. Furthermore, while in the countryside many young couples shared a house with their extended family, doing so in the city was often perceived as a failure of the migratory project. Having an independent home (even a chabola) was the hallmark of a functioning family and of adaptation to city life.

The chabolas also provided their dwellers with greater freedom to construct their lived space in accordance with specific needs and notions of what could be considered a “good home” (Raymond, 1974: 213–229). Most of the chabolas that were documented by the Spanish Ministry of Housing included a central space located at the entrance to the house, which functioned as a living room and was dedicated to socialization and eating. In some of the larger and more established chabolas this space also included a permanent kitchen. In most others the kitchen was made of a make-shift fireplace (which could be situated inside or outside of the chabola depending on the weather) and several chairs. The same space was converted at night into an additional bedroom (Ofer, 2017; 58–79). By forming make-shift bedrooms the dwellers were able to attain a certain level of coherence between the representations of “adequate” sleeping space (which dictated separation according to age and gender) and their lived (or representational) space.

The precarious structure of the chabola allowed for a temporary division of its internal space in accordance with the changing profile of the family that inhabited it. It also allowed its inhabitants to “expel’ certain functions to the outer perimeter of the house according to weather conditions and to the structure and characteristics of communal spaces in the neighbourhood. Some of those functions were “expelled” from the chabola on a temporary basis (as was the case with cooking, eating and studying) and others permanently (bathing for example, which took place outside of the chabola in the case of young children or in public bath-houses at the centre of Madrid in the case of adults).

Figure 11.1 Cooking outdoors in Orcasitas (Asociación de Vecinos del Barrio de Orcasitas, Archivo Fotográfico).

Between the years 2008–2012, I conducted interviews with some of Orcasitas’ original dwellers. In these interviews the old chabolas that had been long demolished were often referred to. María (who grew up in Orcasitas) reflected on the way in which the structure of the chabolas influenced social life within the barrio:

Here we shared everything. The houses were all open. There were no doors, only curtains. You didn’t have to knock. You simply entered, and what you saw was there for the taking. It was for everyone—neighbours, friends, family members.

(María, interview with the author, Orcasitas, Madrid)

Julio (who moved to Orcasitas from the centre of Madrid) recounted:

There were many shanty homes. Some were made of wood, others of exposed brick. They looked like tiny vacation homes. Life was good then, we all knew each other. Now everything is different, we each live in a closed apartment and it’s no longer the same.

(Julio, interview with the author, Orcasitas, Madrid)

The “homely” feeling described above was tied by many of my interviewees to the absence of “transitional spaces.” Lefebvre defined transitional spaces or objects (such as doors, windows and thresholds) that direct the movement from the inside to the outside and vice versa, defining the capacity of one space to connect or merge into another (Lefebvre, 1996: 206). In Orcasitas the open-ended structure of communal and private spaces (most notably exemplified by the lack of doors and fences) promoted a sense of intimacy and of coming together. At the same time, it is important to note that the absence of transitional spaces left the chabolas “naked” in a sense that could also be very dangerous. It enabled the atmosphere and the happenings on the street quite literally to penetrate the private living space of a family. Lacking in walls and doors some of these homes could not be protected from noises, smells or from the presence of outside intruders. The risk inherent in such penetration was felt most acutely when the neighbours were called to protect their homes from demolition, which in the early stages occurred due to the failure to bribe the local representatives of the forces of law and order and later on when the authorities attempted to evacuate the entire population in order to proceed with the process of reconstruction.

The most notable practises which can be identified with spatial appropriation in settlements such as Orcasitas had to do with the provision of services and the construction of communal spaces. As indicated earlier, these practises stood in stark contradiction to the spatial practises that were instituted by the regime within satellite suburbs.

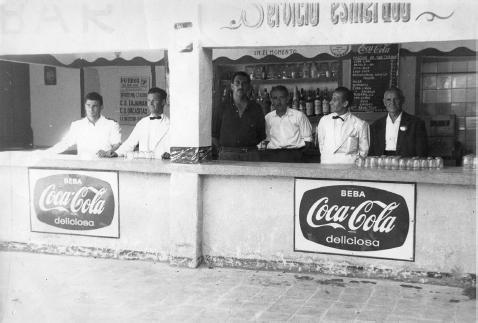

Figure 11.2 Tavern and self-constructed dancing-hall in Orcasitas.

The photos are not dated, but they were taken prior to the first wave of mass demolitions in the 1970s (Asociación de Vecinos del Barrio de Orcasitas, Archivo Fotográfico)

Figure 11.3 Tavern and self-constructed dancing-hall in Orcasitas.

The photos are not dated, but they were taken prior to the first wave of mass demolitions in the 1970s (Asociación de Vecinos del Barrio de Orcasitas, Archivo Fotográfico)

Nearly 6% of the heads of households who lived in Orcasitas in 1958 defined themselves as independent business owners. With the nearest “established” commercial area 3 km away in the barrio of Usera and no public transportation at hand, the businesses that formed in Orcasitas catered for a mixed array of needs. Of the 91 businesses I know of, 12 were bars and taverns (Ofer, 2017: 70–73). They served mainly men and therefore opened on weekends and weekdays from the early afternoon and well into the night. As indicated by their names some of them functioned as hubs of socialization according to the proprietor’s place of origin. Establishments such as La Andaluza, Soria and La Asturiana (which exist to this day) served traditional dishes and drinks and other primary products acquired during trips to the countryside. Other small businesses included a barbershop, fruit shops, bakeries, butcheries, wine shops and several shops for the sale of secondhand clothes and fabrics. To these must be added several mobile businesses for the sale of water and coal.

The Long Road Towards Spatial Appropriation

The construction of an unauthorized school, of a communal fountain, of bars and shops all provide examples of popular production of intermediate or communal spaces. The squatters (in their capacity as consumers, housewives, and parents) identified specific needs that had to be fulfilled. They then proceeded by constructing spaces that could cater for those needs and later on invested them with additional functions and meaning according to the evolution of community life. However, the appropriation of private and intermediate spaces under such conditions should not be confused with laying claim to the urban itself. Henri Lefebvre speculated regarding the potential of spatial change to bring about political change that:

so long as the only connection between work spaces, leisure spaces and living spaces is supplied by the agencies of political power and their mechanisms of control—so long must the project of ‘changing life’ remain no more than a political rallying-cry.

(Lefebvre, 1996: 59)

In order for space to be fully appropriated, it would have to be produced in a way that makes its full and complete usage possible. In this respect the appropriation and creative breaking down of spatial boundaries that took place in squatter settlements across Spain during the 1960s was an essential pre-conditions for change. But a deep and long-lasting transformation of Spain’s urban planning regimes awaited the emergence of a more extended structure of opportunities.

In 1964, the Franco regime sanctioned for the first time the formation of an array of new civic associations on the condition that those would be non political by nature and strictly supervised. Between the years 1968–1975 hundreds of new neighbourhood associations formed all over Spain. Sociologist Manuel Castells wrote of these associations:

This was a large scale movement with an immense popular base. It included [associations] from squatters’ settlements … from middle-class neighbourhoods and those arriving from neighbourhoods situated in the historical centre of Madrid… . It was founded by political activists of different ideological shades and by a multitude of people with no precise ideological inclination who were willing to fight for better living conditions… . The movement obtained the renovation of underprivileged neighbourhoods … and the construction of urban infrastructures not seen before. It reanimated popular cultural and street life … and facilitated forms of self mobilization amongst men and women. It was truly a school of democracy and leadership and made a decisive contribution to popular pressure that propelled the [Spanish] transition to democracy.

(Castells, 2009: 21)

The Orcasitas Neighbourhood Association was founded in 1970, a short time before the local authorities published a Partial Plan for the Reconstruction of Orcasitas. The aim of the plan was to clear the area covered by chabolas, expropriate the land on which they stood and reconstruct a new neighbourhood while dispersing the existing squatter community throughout the Southern periphery of the capital. Aided by a team of lawyers and architects the Orcasitas Neighbourhood Association decided to oppose the implementation of the Plan. Having rejected two modified plans, in 1976 the neighbours finally accepted a third version of the reconstruction plan which was designed according to their needs and would allow them to remain on the land that they had occupied.

The 1976 plan was formulated with the active participation of the neighbours who determined both the internal structure of their apartments and the structure of the entire barrio. How was this done? In early 1976 the architects that worked with the neighbourhood association carried a survey that was intended to verify the priorities of Orcasitas’ future dwellers. They entered the existing chabolas, interviewed the inhabitants and then recorded and analysed the information. One set of questions was intended to collect information on the socio-economic profile of the families (their joint income, the number of people living in the house, whether the family owned a car etc.). The second set included questions that were meant to give the architects an idea about the ways in which each family used its living space. People were asked if they wished to live in a house of a single or multiple floors and whether they preferred to live in a four-storey building without an elevator or a seven-storey building with one (Ofer, 2017: 125–129). They were also asked how far away from the house they were willing to park their cars in order to allow for the safe circulation of pedestrians. The preamble to the new reconstruction plan stated accordingly:

We wish to reproduce the [atmosphere] experienced by the neighbours of Orcasitas, who at the moment live in a barrio made up of a single-storey houses, and in which the street is used and valued in its original form… . We wish to mix housing spaces with other spaces intended for commerce… . We want to reduce to a minimum the height of the buildings. This is the preference expressed by all of the neighbours, who indicated they did not want to live in high-rise apartments nor be surrounded by high buildings.

(Polígono Meseta de Orcasitas, Hoja Informativa no. 3— La manzana, editada por el equipo de técnicos de la asociación de vecinos, the author’s translation)

The new barrio was divided into six residential nuclei (which included a mix of four, eight and ten storey buildings) and structured around a Civic Centre (which to this day serves as the heart of community life in Orcasitas and houses the neighbourhood association). Each nucleus was made up of 8–10 apartment buildings that were arranged around a small courtyard and a commercial space. The ground floor of each apartment building included a nursery and a playroom for the children. The aim was to create multi-scalar spaces for socialization—from the playrooms in each building, to the courtyard that united several buildings and up to the Civic Centre and its large plaza.

In 1986, the neighbours of Orcasitas celebrated the inauguration of the new barrio with an exposition on 15 years of struggle (housed in the new headquarters of the neighbourhood association). In a final act which perhaps best symbolized the control they gained over their renovated living space, the neighbours named their streets. The action of naming indicated a move from the stage of an active struggle to the stage of memory conservation. Calle de la Remodelación (re-modeling), calle de los Encierros (lock-downs), Plaza del Movimiento Ciudadano (Citizens’ Movement) are some of the more interesting names in present-day Orcasitas.

José Manuel Bringas, who was the first architect to join the technical advisory team in Orcasitas, wrote about the process of informed election that culminated in a plan for the new barrio:

there are those who talk negatively of the architects [turned] activists. I did not infiltrate the association under the pretext of advising the people in order to agitate and propel them into a struggle against those in power. Anyone who knows the story of the struggle in Orcasitas personally would burst out laughing when hearing these accusations. In the Mesta no one had to agitate, no one! Not the president [of the association], not the members of the directive committee, not the technical advisors. The entire Meseta agitated if the people were made aware that something threatened their re-modeling project… . In this type of work the ‘technical advisor’, in his capacity to offer technical or academic solutions, can not be replaced by a neighbour. At the same time it is important that he or she understand that their job is to accompany the neighbours in managing [and assessing] the solutions that are being offered to them. No more and no less than that.

(Meseta de Orcasitas, 1982: 7–8, the author’s translation)

Figure 11.4 The Structure of a Housing Nucleus, including Towers, Four-storey Apartment Buildings and Commercial and Recreational Spaces (Polígono Meseta de Orcasitas, Hoja informativa no. 3—la Vivienda, Equipo de técnicos de la asociación de vecinos de Orcasitas).

Bringas’ words point to developments that allowed the dwellers of Orcasitas to progress from the appropriation of their lived space and onto claiming the city in a fuller sense. Achieving the latter necessitated an understanding that controlling and shaping lived space had political implications. A right to the city was a right for spatial appropriation as well as for political participation. As Mark Purcell noted Lefebvre’s right to the city was not a suggestion for reform. Rather, it was a call for:

a radical restructuring of social, political, and economic relations, both in the city and beyond. Key to this radical nature is that the right to the city reframes the arena of decision-making in cities: it reorients decision-making away from the state and toward the production of urban space. Instead of democratic deliberation being limited to just state decisions, Lefebvre imagines it to apply to all decisions that contribute to the production of urban space. The right to the city stresses the need to restructure the power relations that underlie the production of urban space.

(Purcell, 2002: 102)

He further elaborates:

Because the right to the city revolves around the production of urban space, it is those who live in the city—who contribute to the body of urban lived experience and lived space—who can legitimately claim the right to the city. Whereas conventional enfranchisement empowers national citizens, the right to the city empowers urban inhabitants. Under the right to the city, membership in the community of enfranchised people is not an accident of nationality or ethnicity or birth; rather it is earned by living out the routines of everyday life in the space of the city.

(Ibid.)

In the case of Orcasitas, spatial appropriation clearly generated new forms of urban knowledge. The development of a new professional and communitarian platform (in the form of a neighbourhood association) enabled such knowledge in its turn to be translated into a professional idiom and transferred into the realm of policy making. However, it is enough to look at present day Orcasitas in order to understand the limitations of change. The new barrio of Orcasitas was constructed as a neighbourhood onto itself. It might have been conceived as a perfectly formed barrio on the inside, but throughout the 1980s and 1990s it had little sustainable ties with the city around it. On a practical level this is best manifested by the fact that Orcasitas was only directly connected to the Madrid Metro line in 2008. More disquieting, however, is the fact that in the decades following the renovation the barrio was referred to in the Madrid press either in relation to its successful past struggle or as a current hotbed of criminal activity and of drug trafficking. While the neighbours struggled to combat drug consumption within the community, many outsiders viewed drug trafficking as one of the characteristics of the barrio itself. In other words, the empowering struggle and the consequent re-modelling process changed some of the existing spatial practises and the structure of representational space within the barrio. But it did not bring about a lasting change in the representations of that space as a marginalized periphery in the eyes of those living outside of the barrio.

Conclusion: A Democratic City versus an Open City

The current chapter analyses the ways in which micro-level research into the formal and informal practises of urban planning can benefit from Lefebvre’s spatial analysis. It also raises several theoretical questions to which Lefebvre only briefly alluded in his work. Lefebvre’s triad model provides us with a valuable framework for the analysis of spatial production. It highlights the ways in which space is produced through the evolution of competing practises and representation promoted by different stakeholders. However, Lefebvre did not refer explicitly in his work to the possibility that contradictions might surface between the spatial representations and the practises promoted by the same stakeholder (such as the state, city-council etc.). In reality this might happen quite often. The political and economic forces which are engaged in monitoring and shaping urban space often share common goals. But even in the rare cases where complete correlation exists between the needs and aspirations of economic and political actors, contradictions might still surface between the spatial practises which those actors promote and the representations employed in order to justify them. Under such conditions the experience of lived space (affected as it is by both) can either work in order to minimize tensions and “cover up” the contradictions, or in order to make these tensions explicit, thereby undermining the process of spatial domination. If the latter occurs we may see the beginning of a process by which urban space is claimed by its users.

In the Spanish case, the new administration which elected followed the transition to democracy clearly sought to change the exiting urban planning regimes. In Madrid, Barcelona and Bilbao the local authorities spent a large percentage of their budgets on the extension of public infrastructures. Peripheral neighbourhoods were finally brought into contact with the city through the construction of an extended system of roads, electricity and water provision facilities. Green spaces and recreational facilities were expanded all throughout the city. However, the process by which the urban was developed as a space characterized by a single gravity point (structured around a main locus of industry, services and infrastructures) and multiple peripheries was never fully reversed. The “periphery” was connected to the “centre” and gained recognition as an integral part of the city but never became a centre in itself.

The process by which the incorporation of lessons gained from the experience of informal urbanization into the new urban planning regime took place highlights, in my view, the difference between the idea of a democratic city and an “open” city. It is the latter which embodies more fully Lefebvre’s notion of the “right to the city.” Sociologist Richard Sennett defined the open city as a city in which constant interaction exists between physical creation and social behaviour (Sennett, 2006). Sennett suggested three design characteristics that may influence the “openness” of a city: the existence of ambiguous edges between parts of the city where different groups can interact; the creation of incomplete forms so that as the function of a building or a space changes historically so will its form; and the planning for unresolved narratives of development allowing the planner to follow rather than determine the development of urban space.

It is on the first account that the Plan for the Reconstruction of Orcasitas failed most profoundly. Urban reconstruction plans for the metropolitan area of Madrid that were approved following Spain’s transition to democracy worked to diminish the hierarchical structure which the planners of the 1940s and 1950s strove to implement. The Plan for the Remodelling the Neighbourhoods of Madrid (Programa de Barrios en Remodelación) which was executed between the years 1979–1988, for example, created multiple commercial, cultural and educational hubs throughout the city. It also reformed the workings of the local administration, enhanced its contact with ordinary citizens, and decentralized the provision of services to the local population. However, the border between the southern periphery of the capital and its centre remains as unambiguous as the river Manzanares, which marks it. While the population of the southern barrios crosses the river in search of work, commerce and entertainment the periphery still has very little to offer in the minds of those living on the other bank of the Manzanares.

Finally, both Sennett’s concept of the “Open City” and Lefebvre’s concept of “right to the city” are based on an understanding the urban is not only the hegemonic scale at which planning is carried-out but that it should also be the level at which the political community is defined. Under the new liberal democratic state the urban continued to expand, while this particular re-scaling of the concept of citizenship was never defined as a corresponding goal. In the decade following 1986, trucks of neighbours from the southern periphery of Madrid would still occasionally pour into the capital’s central Plaza. Men, women and children protested crowded classes, lack of transportation services, the administration’s failure to deal with increased unemployment and drug-related problems. However, the dream of a more participatory form of government never materialized. The activists who strove to achieve higher levels of civic participation felt excluded from the beating heart of the local and the national administration. The willingness of democratic authorities to allow the “community” to take an active part in designing and regulating its living-environment was limited. Within the framework of a liberal democracy the Spanish state guaranteed an extended list of essential rights. Continued civic participation at all levels of governance, however, was never perceived as one of those rights. But it was precisely the right for active, innovative and creative participation based on the insights derived from an on-going practice of inhabiting the city, which lay at the heart of the Orcasitas success. Without it, as most neighbourhood activists understood, the ability of ordinary citizens to shape their lived space could not be sustained over time.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 54/10).

References

Anders, F. and Sedlmaier, A. (Eds). (2017). Public Goods versus Economic Interests: Global Perspectives on the History of Squatting. Abingdon: Routledge Studies in Modern History, Routledge.

Brenner, N. and Elden, S. (2009). Henri Lefebvre on state space and territory. International Political Sociology, 3(4), 353–377.

Brenner, N., Marcuse, P. and Mayer, M. (2012). Cities for People Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. London: Routledge.

Brun, J. and Rhein, C. (1994). La ségrégation dans la ville (pp. 21–57). Paris: L’Harmattan.

Bilbao Larrondo, L. (2006). La Vivienda en Bilbao: Los años sesenta. Años de cambio. Ondare. Cuadernos de Artes Plásticas y Monumentales, 25, 81–86.

Box Varela, Z. (2008). La fundación de un régimen. La construcción simbólica del franquismo (Tesis doctoral). Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Brillembourg, C. (2006). José Castillo: Urbanism of the informal. Bomb Magazine, 94(winter), 28–35. Retrieved from http://www.bombsite.com/issues/94/articles/2798 Google Scholar

Capel Sáez, H. (1962). Las Migraciones Interiores Definitivas en España. Estudios Geográficos, XXIV, 600–602.

Castells, M. & Portes, A. (1989). World underneath: The origins, dynamics and the effects of the informal economy. In A. Portes, M. Castells, L. Benton (Eds.), The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries (pp. 11–37). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Castells, M. (2009). Productores de ciudad: el movimiento ciudadano de Madrid in Pérez. In V. Quintana and P. Sánchez León (Eds.), Memoria Ciudadana y movimiento vecinal. Madrid 1968–2008 (pp. 21–32). Madrid: Catarata.

COPLACO (1977). Informe sobre participación pública en el planeamiento metropolitan. Madrid: Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo.

de Souza Briggs, X. (2005). Social capital and segregation in the United States. In Varady D. P. (Ed.), Desegregating the City: Ghettos, Enclaves and Inequality (pp. 79–101). New York: State University of New York.

Elden, S. (2004). Understanding Henri Lefebvre. Theory and the Possible. London: Continuum.

Grafmayer, Y. (1994). Regards sociologiques sure la segregation. In La Ségrégation dans la ville (pp. 85–117). Paris: L’Harmattan.

Higueras, Arnal, A. (1967). La Emigración Interior en España. Madrid: Ediciones Mundo del Trabajo.

Hoskyns, T. (2014). The Empty Place. Democracy and Public Space. London: Routledge.

Le Corbusier (1973). The Athens Charter (translated by A. Eardely). New York: Grossman Publishers.

Lehman-Frisch, S. (2011). Segregation, spatial (in)justice, and the city. Berkeley Planning Journal, 24(1), 70–90.

Lefebvre, H. (1976). The Survival of Capitalism: Reproduction of the Relations of Production (translated by F. Bryant). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1976–78). De l‘État. Paris: UGE.

Lefebvre, H. (1991a). The Production of Space (translated by D. Nicholson-Smith). Oxford: Blackwell.

Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities (translated and introduced by E. Kofman and E. Lebas). Oxford: Blackwell.

Lefebvre, H. (2003a). Key Writings (edited by S. Elden, E. Lebas and E. Kofman). London: Continuum.

Lefebvre, H. (2003b). The Urban Revolution (translated by R. Bonnano). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Leloup, X. (1999). “Distance et différence entre nationalité: La ségrégation résidentielle des populations étrangères dans un contexte urbain.” Recherches Sociologiques, 1.

Mayer, M. (2012). The “right to the city” in urban social movements. In N. Brenner, P. Marcuse, and M. Mayer (Eds.), Cities for People Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City (pp. 63–85). London: Routledge.

Meseta de Orcasitas (1982). Boletín Informativo, no. 1 (abril).

Ofer, I. (2017). Claiming the City and Contesting the State Squatting, Community Formation and Democratisation in Spain (1955–1986). London: Routledge.

Park, R. E. (1926). The urban Community as a Spatial Pattern and Moral Order. In R. H. Turner (Ed.), Robert E Park on Social Control and Collective Behavior. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Purcell, M. (2002). Excavating Lefebvre: The right to the city and urban politics of the inhabitants. GeoJournal, 58, 99–108.

Purcell, M. (2003). Citizenship and the right to the global city: Reimagining the capitalist world order. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(3), 564–590.

Raymond, H. (1974). Habitat, modèles cultureless et architecture. In H. Raymond, J. M. Stébé and A. Mathieu Fritz (Eds.), Architecture urbanistique et société (pp. 213–229). Paris: L’Harmattan.

Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158.

Sambricio, C. (2004). Madrid, vivienda y urbanismo: 1900–1960. Madrid: AKAL.

Sennet, R. (2006). The Open City, LSE Cities. Retrieved from https://lsecities.net/media/objects/articles/the-open-city/en-gb/

Shields, R. (1999) Lefebvre, Love and Struggle. London: Routledge.

Siguán, M. (1959). Del campo al suburbio. Un estudio sobre la inmigración interior en España, Madrid: C. S. I. C.

Stanek, L. (2011). Henri Lefebvre on Space. Architecture, Urban Research, and the Production of Theory, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Terán, F. (1982). Planeamiento urbano en la españa contemporanea (1900–1980). Madrid: Alianza Universidad Textos.