EXHIBIT 2-1

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

| 2-1 | Define skimming |

| 2-2 | List and understand the two principal categories of skimming schemes |

| 2-3 | Understand how sales skimming is committed and concealed |

| 2-4 | Understand schemes involving understated sales |

| 2-5 | Understand how cash register manipulations are used to skim currency |

| 2-6 | Be familiar with how sales are skimmed during nonbusiness hours |

| 2-7 | Understand the techniques discussed for preventing and detecting sales skimming |

| 2-8 | List and be able to explain the six methods typically used by fraudsters to conceal receivables skimming |

| 2-9 | Understand what “lapping” is and how it is used to hide skimming schemes |

| 2-10 | Be familiar with how fraudsters use fraudulent write-offs or discounts to conceal skimming |

| 2-11 | Understand the techniques discussed for preventing and detecting receivables skimming |

| 2-12 | Be familiar with proactive audit tests that can be used to detect skimming |

CASE STUDY: SHY DOC GAVE GOOD FACE1

Brian Lee excelled as a plastic surgeon. His patients touted Lee's skill and artistry when privately confiding the secret of their improved appearance to their closest friends. Exuding a serious, gentle manner, the forty-two-year-old bachelor took quiet pride in his beautification efforts—mainly nose jobs, face lifts, tummy tucks, and breast enhancements.

Lee practiced out of a large physician-owned clinic of assorted specialties, housed in several facilities scattered throughout a growing suburb in the Southwest. As its top producer, Lee billed more than $1 million annually and took home $300,000 to $800,000 a year in salary and bonus. But during one four-year stretch, Lee also kept his own secret stash of unaccounted revenue—possibly hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Once Lee's dishonesty came to light, the clinic's board of directors (made up of fellow physician-shareholders) demanded an exact accounting. The clinic's big-city law firm hired Doug Leclaire, a certified fraud examiner (CFE) based in Flower Mound, Texas, who had worked well with the lawyers earlier that year on an unrelated case, to conduct a private investigation.

“The doctors wanted an independent person to root around and document how much money was missing,” recalled Leclaire. “They also wanted to see how deep this scam ran. As far as I could determine, no one else was involved.” Lee's secretary and nurse knew that Lee was performing the surgeries, but they were unaware that the doctor was withholding patient payments from the clinic. Leclaire marveled at the simplicity of the fraud. He said Lee's ill-gotten gains came easily, given the discreet nature of his business.

Leclaire first familiarized himself with both clinic and office policies. (Doctors ran their offices as autonomous units.) During a confidential, free consultation, Lee would examine the patient and explain various options, the expected results, and his total fee. The doctor or his secretary would then discuss payment requirements.

According to Leclaire, “If the patient planned on filing an insurance claim for covered procedures—such as nonemergency, reconstructive surgery for a car crash victim whose nose smashed into a windshield—the patient must pay the deductible beforehand.” For pure cosmetic surgery such as liposuction, which is not covered by insurance, patients had to pay the entire amount by cash or check prior to the procedure. Like many plastic surgeons, Lee accepted no credit cards, presumably to guard against economic reprisals from “buyer's remorse.” The one-time payment included all post-op visits as well.

Once a patient decided to go under the knife, Lee or his secretary would schedule another appointment or review the doctor's master surgery log to schedule a mutually agreeable date and time. Lee performed the surgeries at the clinic or an affiliated hospital. In theory, a patient would check in at the reception area for a scheduled procedure and pay the secretary, who would immediately attach the payment along with an accompanying receipt to the appropriate procedure form and record the transaction on a daily report. The secretary kept all payments, receipts, and forms in a small lockbox for temporary safekeeping.

“At the end of the day, either the doctor, his nurse, or his receptionist would submit all paperwork and payments—easily totaling tens of thousands of dollars—to the clinic cashier across the hall,” explained Leclaire. “If it was late in the day, the doctor would sometimes lock the box in his desk drawer until the following day.” For procedures performed at an affiliated hospital, the patient paid in advance, and the clinic relied on someone from the doctor's office to submit the completed paperwork to the head cashier, allowing the clinic to declare its cut.

But even the best-laid plans often fail in their execution, noted Leclaire. The case that finally nailed the plastic surgeon was that of Rita Mae Givens, a rhinoplasty patient. The clinic offices were arranged so that when a patient stepped off the elevator, they could turn right and enter the clinic's main reception area, or turn left and walk down the hall to enter Lee's office reception area. Getting off the elevator on to the fifth floor, Givens proceeded to her left as Lee had earlier instructed. Givens gained admittance via Lee's private office door, bypassing the clinic secretary and receptionist down the hall on the right. As planned, the unsuspecting clinic staff never knew that Lee made the appointment with Givens nor that he performed surgery to correct her deviated septum and trim her proboscis. Givens had paid the doctor by check.

During her recovery, Givens reviewed her insurance policy, which stated that rhinoplasty may be covered under certain circumstances, or at least may count toward meeting the yearly deductible. She decided to file an insurance claim. But Givens realized she had never received a billing statement to attach to her claim form, which was mandated by her carrier. So Givens made an unplanned call to the clinic's office to request a copy of her bill, which then setoff a series of spontaneous reactions. Lee's clinic's cashier located the patient's file, but it showed no charges for the procedure performed. The cashier thought this quite odd. Givens assured the cashier that the procedure had been performed and that she had paid for the surgery with a personal check.

The cashier in turn checked with the office manager of the clinic for the corresponding record of Givens's payment. Of course the office manager failed to find the record and called the clinic administrator in on the search. Knowing that doctors sometimes forgot to immediately reconcile procedures performed at other facilities, the clinic administrator suggested they look at the doctor's surgery log, under the time and date that Givens had provided, for any clues. Meanwhile, the office manager asked the patient to provide a copy of her canceled check, which they later discovered had been endorsed and deposited in the doctor's personal bank account.

The clinic administrator verified that Lee had performed the surgery but had never submitted the payment to the head cashier. When confronted, the doctor admitted his wrongdoing. The administrator alerted the board, which then hired Leclaire to investigate.

The private eye interviewed Lee several times over the course of the investigation. Leclaire described Lee as very apologetic and helpful in reviewing his misdeeds. The doctor only stole payments from elective surgery patients, he explained, so as not to alert any insurance providers who may have requested additional documentation from the clinic. Sometimes Lee helped himself to payments in his secretary's lockbox before turning it in to the head cashier. Sometimes he swiped a payment directly from a patient with a surreptitious appointment. He preferred cash, but often took checks made payable to “Dr. Lee.” The doctor often held checks in his desk drawer for a few weeks before depositing them into his personal bank account or cashing the checks. Lee simply destroyed the receipts that were to accompany payments, he told Leclaire. Out of a sense of professional duty, Lee scrupulously maintained all patient medical files, though.

Because the perpetrator cooperated so fully, Leclaire called this case “fun and easy.” The doctor kept meticulous records of all his actions, whether or not they were legitimate. With Lee's help, Leclaire compared the doctor's detailed “Day Timer” personal organizer against the clinic's records and readily identified the missing payments. Lee even turned over his bank statements so Leclaire could match the deposits to the booty. Lee also opened up his investment portfolio to Leclaire to quash any doubts over additional unreported revenue.

“The doctor didn't try to hide anything,” said Leclaire, who has spent twenty years conducting criminal investigations. “I was able to document everything.” In all his talks with the doctor, “Everything he told us was pretty much on the up and up.”

After spending so much time with the doctor, Leclaire finally asked Lee the one question that everyone puzzled over—Why? Greed, he said. With all his money, he still craved more. Driven like his father and brother, who are also successful, Lee had little time to enjoy sports and recreation. Wealth was the family obsession, one-upmanship the family game. “It grew to be a serious competition,” said Leclaire. “Who could amass the most? Who had the best car?”

To win the game, Lee resorted to grand larceny, which carried an enormous risk of punishment should the fraud be detected. “I kind of felt sorry for the doctor. A guy in that position could have lost everything,” Leclaire said.

After weeks of work, the law firm and its private investigator brought their findings to the board and made recommendations as requested. He prefaced his report with lessons that were learned from this case. “Weak internal controls tempt all employees, even those earning over $100,000. If given the opportunity, means, and a very slim chance for detection, there are employees who will justify the commission of a fraud in their own minds.”

Leclaire suggested they revamp their entire payment system, setting up a central billing area, posting signs to educate the patients, and assigning and spreading out distinct tasks to several office workers during the payment process. “They had no oversight,” said the investigator. He told them they needed to reconcile all steps along the way and perform routine internal audits.

This fraud escaped detection for more than four years, Leclaire told his attentive audience. The bottom line? By his audit, Lee had embezzled about $200,000.

Much discussion and a question-and-answer period followed. Some board members insisted Lee be terminated immediately. “Others showed real sympathy for one of their brethren,” said Leclaire.

“Their biggest concern was the clinic's income tax liability.” Leclaire, who had been a special agent with the IRS's criminal investigations department for nine years, assured them the clinic held no liability for uncollected income. No one wanted an IRS audit, given the clinic's history of scant oversight and the doctors' uncertainty over their own culpability, said Leclaire. They feared federal agents would snoop around and perhaps find other instances of unreported income or questionable activity. He warned that taxes would definitely be due upon restitution, however.

“The doctors had worked out an agreement among themselves.” They decided not to prosecute or terminate Lee. Of course the doctors expected Lee to make immediate and full restitution of $200,000, plus interest. (For the first installment, Leclaire picked up $15,000 in cash the doctor had lying around his modest abode.) They also insisted that Lee place another $200,000 in escrow to cover any contingencies. And naturally, the doctor would foot the bill for both the lawyers and the private investigator involved in the case.

His fellow physicians agreed to let their top moneymaker continue to practice at the clinic provided Lee went for professional counseling to correct his aberration. They would help him any way they could, they said. Encouraged to show Lee there were other things in life besides work, from then on the doctors invited him along on their fishing and hunting trips. On the advice of his psychiatrist, Lee eagerly accepted. The reformed loner even enjoyed himself.

To curb temptations, the clinic immediately instituted new policies on payment procedures. Good thing, said Leclaire: the good doctor later told him that if given a chance, “I would probably do it again.”

OVERVIEW

Skimming, as illustrated in the previous case, is the theft of cash from a victim entity prior to its entry in an accounting system. Because the cash is stolen before it has been recorded in the victim company's books, skimming schemes are known as “off-book” frauds, and since the missing money is never recorded, skimming schemes leave no direct audit trail. Consequently, it may be very difficult to detect that the money has been stolen. This is the principal advantage of a skimming scheme to the fraudster.

Skimming can occur at any point where funds enter a business, so almost anyone who deals with the process of receiving cash may be in a position to skim money. This includes salespeople, tellers, waitstaff, and others who receive cash directly from customers. In addition, employees whose duties include receiving and logging payments made by customers through the mail perpetrate many skimming schemes. These employees are able to slip checks out of the incoming mail for their own use rather than posting the checks to the proper revenue or customer accounts. Those who deal directly with customers or who handle customer payments are, clearly, the most likely candidates to skim funds.

Skimming Data from the ACFE 2011 Global Fraud Survey

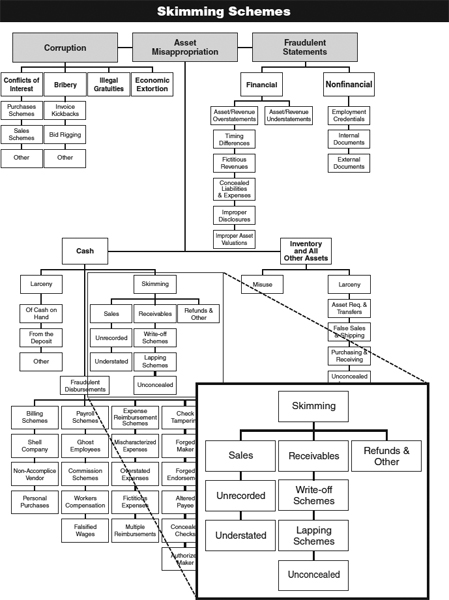

In Chapter 1, we learned that there are three major categories of occupational fraud: asset misappropriations, corruption, and fraudulent statements. We further learned that asset misappropriation schemes are the most common of these categories; of the 1,388 cases in the study, 1,204, or almost 87 percent, involved some form of asset misappropriation.

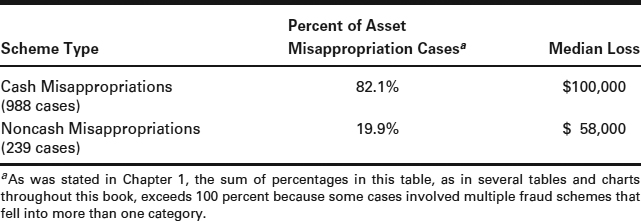

As the fraud tree (Exhibit 2-1) illustrates, asset misappropriations can in turn be subdivided into two categories: cash schemes and noncash schemes. Exhibit 2-2 shows the percentage of asset misappropriation cases and median losses for each of these two subcategories. As we see, cash schemes were much more common than noncash schemes in the ACFE's 2011 Global Fraud Survey and also tended to have a higher median cost.

It is important to note that because fraudsters often utilize a variety of tactics to pilfer the victim's money, many fraud schemes involve multiple methods of fraud. Thus, ACFE researchers asked respondents to the survey to identify both the total loss caused by the fraud and the amount of the loss directly attributable to each specific type of asset misappropriation scheme. This subdivision provides a more accurate picture of the effects of asset misappropriation schemes than previously obtained. Consequently, the median loss amounts reported throughout this text reflect just that portion of the fraud loss attributable to the specific scheme being discussed.

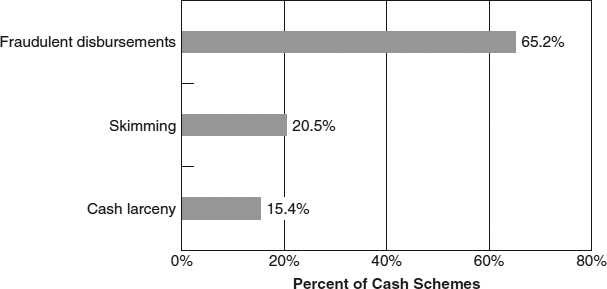

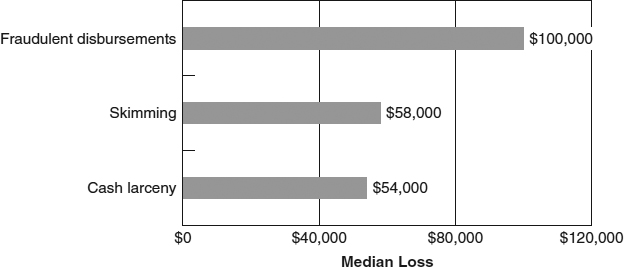

Again returning to the fraud tree, cash schemes are subdivided into three distinct categories: skimming, cash larceny, and fraudulent disbursements. Among these subcategories, fraudulent disbursement schemes were the most common, occurring in nearly two-thirds of the cash misappropriation cases included in the study. These schemes also caused the highest median loss ($100,000) of the three cash scheme categories. In contrast, skimming and cash larceny schemes were a part of 21 percent and 15 percent of the cash misappropriation cases, respectively, and caused respective median losses of $58,000 and $54,000 (see Exhibits 2-3 and 2-4).

EXHIBIT 2-3 2011 Global Fraud Survey. Frequency of Cash Misappropriations

EXHIBIT 2-3 2011 Global Fraud Survey. Frequency of Cash Misappropriations

EXHIBIT 2-4 2011 Global Fraud Survey: Median Loss of Cash Misappropriations

SKIMMING SCHEMES

Skimming schemes all follow the same basic pattern: an employee steals incoming funds before they are recorded in the victim organization's books. Within this broad whole, skimming schemes can be subdivided based on whether they target sales or receivables. The character of the incoming funds has an effect on how the frauds are concealed, and concealment is the crucial element of most occupational fraud schemes.

Sales Skimming

The most basic skimming scheme occurs when an employee makes a sale of goods or services to a customer, collects the customer's payment at the point of sale, but makes no record of the transaction. The employee pockets the money received from the customer instead of turning it over to his employer (see Exhibit 2-5). This was the method used by Dr. Brian Lee in the case study discussed previously. He was performing work and collecting money that his partners knew nothing about. As a result he was able to take approximately $200,000 without leaving any indications of his wrongdoings on the books. Had a patient not made an unexpected call for a copy of a billing statement, Lee's crime could have gone on indefinitely. The case of Dr. Lee illustrates why unrecorded sales schemes are perhaps the most dangerous of all skimming frauds.

EXHIBIT 2-5 Unrecorded Sales

In order to discuss sales skimming schemes more completely, let us consider one of the simplest and most common sales transactions, a sale of goods at the cash register. In a normal transaction, a customer purchases an item—such as a pair of shoes—and an employee enters the sale on the cash register. The register tape reflects that the sale has been made and shows that a certain amount of cash (the purchase price of the item) should have been placed in the register. By comparing the register tape to the amount of money on hand, it may be possible to detect thefts. For instance, if $500 in sales is recorded on a particular register on a given day, but only $400 cash is in the register, someone has obviously stolen $100 (assuming no beginning cash balance).

When an employee skims money by making off-book sales of merchandise, however, the theft cannot be detected by comparing the register tape to the cash drawer, because the sale was never recorded on the register. Think of the example in the preceding paragraph: Assume a fraudster wants to make off with $100, and there are $500 worth of sales at that employee's cash register through the course of the day. Also assume that one sale involves a $100 pair of shoes. When the $100 sale is made, the employee does not record the transaction on his register. The customer pays $100 and takes the shoes home, but instead of placing $100 in the cash drawer, the employee pockets it. Since the employee did not record the sale, at the end of the day the register tape will reflect only $400 in sales. There will be $400 on hand in the register ($500 in total sales minus the $100 that the employee stole), so the register will balance. By not recording the sale, the employee was able to steal money without the missing funds appearing on the books.

Cash Register Manipulation The most difficult part in a skimming scheme at the cash register is that the employee must commit the overt act of taking money. If the employee takes the customer's money and shoves it into his pocket without entering the transaction on the register, the customer may suspect that something is wrong and report the conduct to another employee or manager. It is also possible that a manager, a fellow employee, or a surveillance camera will spot the illegal conduct.

In order to conceal their thefts, some employees might ring a “no sale” or other noncash transaction on their cash registers to mask the theft of sales. The false transaction is entered on the register so that it appears a sale is being rung up when in fact the employee is stealing the customer's payment. To the casual observer, it looks as though the sale is being properly recorded.

In other cases, employees have rigged their cash registers so that sales are not recorded on their register tapes. As we have stated, the amount of cash on hand in a register may be compared to the amount showing on the register tape in order to detect employee theft. It is thus not important to the fraudster what is keyed into the register, but rather what shows up on the tape. If an employee can rig the register so that sales do not print, he can enter a sale that he intends to skim, yet ensure that the sale never appears on the books. Anyone observing the employee will see the sale entered, see the cash drawer open, and so forth, yet the register tape will not reflect the transaction. How is this accomplished? In Case 1740,1 a service station employee hid stolen gasoline sales by simply lifting the ribbon from the printer. He then collected and pocketed the sales that were not recorded on the register tape. The fraudster would then roll back the tape to the point where the next transaction should appear and replace the ribbon. The next transaction would be printed without leaving any blank space on the tape, apparently leaving no trace of the fraud. However, the fraudster in this case overlooked the fact that the transactions on his register were prenumbered. Even though he was careful in replacing the register tape, he failed to realize that he was creating a break in the sequence of transactions. For instance, if the perpetrator skimmed sale #155, then the register tape would show only transactions #153, #154, #156, #157, and so on. The missing transaction numbers, omitted because the ribbon was lifted when they took place, indicated fraud.

Special circumstances can lead to more creative methods for skimming at the register. In Case 2230, for instance, a movie theater manager figured out a way around the theater's automatic ticket dispenser. In order to reduce payroll hours, this manager sometimes worked as a cashier selling tickets. He made sure that at these times there was no one checking patrons' tickets outside the theaters. When a sale was made, the ticket dispenser would feed out the appropriate number of tickets, but the manager withheld tickets from some patrons and allowed them to enter the theater without them. When the next customer made a purchase, the manager sold the person one of the excess tickets instead of using the automatic dispenser. Thus, portions of the ticket sales were not recorded. At the end of the night, there was a surplus of cash, which the manager removed and kept for himself. Although the actual loss was impossible to measure, it was estimated that this manager stole over $30,000 from his employer.

After Hours Sales Another way to skim unrecorded sales is to conduct sales during nonbusiness hours. For instance, some employees have been caught running their employers' stores on weekends or after hours without the knowledge of the owners. They were able to pocket the proceeds of these sales because the owners had no idea that their stores were even open. One manager of a retail facility in Case 2103 went to work two hours early every day, opening his store at 8:00 a.m. instead of 10:00 a.m., and pocketed all the sales made during these two hours. Talk about dedication! He rang up sales on the register as if it was business as usual, but then removed the register tape and all the cash he had accumulated. The manager then started from scratch at 10:00 as if the store was just opening. The tape was destroyed, so there was no record of the before-hours revenue.

Skimming by Off-Site Employees Though we have discussed skimming so far in the context of cash register transactions, skimming does not have to occur at a register or even involve hard currency. Employees who work at remote locations or without close supervision perpetrate some of the most costly skimming schemes. This can include independent salespersons who operate off-site and employees who work at branches or satellite offices; these employees have a high level of autonomy in their jobs, which often translates into poor supervision, and that, in turn, to fraud.

Several cases reported as part of the ACFE studies involved the skimming of sales by off-site employees. Some of the best examples of this type of fraud occurred in the apartment rental industry, where apartment managers handle the day-to-day operations without much oversight. A common scheme, as evidenced by a bookkeeper in Case 250, is for the perpetrator to identify the tenants who pay in currency and remove them from the books. This causes a particular apartment to appear as vacant on the records when, in fact, it is occupied. Once the currency-paying tenants are removed from the records, the manager can skim their rental payments without late notices being sent to the tenants. As long as no one physically checks the apartment, the fraudster can continue skimming indefinitely.

Another rental-skimming scheme occurs when apartments are rented out but no lease is signed. On the books, the apartment will still appear to be vacant, even though there are rent-paying tenants on the premises. The fraudster can then steal the rent payments, which will not be missed. Sometimes the employees in these schemes work in conjunction with the renters and give a “special rate” to these people. In return, the renter's payments are made directly to the employee and any complaints or maintenance requests are directed only to that employee so the renter's presence remains hidden.

Instead of skimming rent, the property manager in Case 1381 skimmed payments made by tenants for application fees and late fees. Revenue sources such as these are less predictable than rental payments, and their absence may therefore be harder to detect. The central office in Case 1381, for instance, knew when rent was due and how many apartments were occupied, but had no control in place to track the number of people who filled out rental applications or how many tenants paid their rent a day or two late. Stealing only these nickel-and-dime payments, the property manager in this case was able to make off with approximately $10,000 of her employer's money.

A similar revenue source that is unpredictable, and therefore difficult to account for, is parking lot collection revenue. In Case 2045, a parking lot attendant skimmed approximately $20,000 from his employer simply by not preparing tickets for customers who entered the lot. He would take the customers' money and wave them into the lot, but because no receipts were prepared by the fraudster, there was no way for the victim company to compare tickets sold to actual customers at this remote location. Revenue sources that are hard to monitor and predict, such as late fees and parking fees in the examples above, are prime targets for skimming schemes.

Another off-site person in a good position to skim sales is the independent salesperson. A prime example is the insurance agent who sells policies but does not file them with the carrier. Most customers do not want to file claims on a policy, especially early in the term, for fear that their premiums will rise. Knowing this, the agent keeps all documentation on the policies instead of turning it in to the carrier. The agent can then collect and keep the payments made on the policy because the carrier does not know the policy exists. The customer continues to make his payments, thinking that he is insured, when in fact the policy is a ruse. Should the customer eventually file a claim, some agents are able to backdate the false policies and submit them to the carrier, then file the claim so that the fraud will remain hidden.

Poor Collection Procedures Poor collection and recording procedures can make it easy for an employee to skim sales or receivables. In Case 1679, for instance, a governmental authority that dealt with public housing was victimized because it failed to itemize daily receipts. This agency received payments from several public housing tenants, but at the end of the day, “money” received from tenants was listed as a whole. Receipt numbers were not used to itemize the payments made by tenants, so there was no way to pinpoint which tenant had paid how much. Consequently, the employee in charge of collecting money from tenants was able to skim a portion of their payments. She simply did not record the receipt of over $10,000. Her actions caused certain accounts receivable to be overstated where tenant payments were not properly recorded.

Understated Sales The cases discussed above dealt with purely off-book sales. Understated sales work differently in that the transaction is posted to the books, but for a lower amount than the perpetrator collected from the customer (see Exhibit 2-6). For instance, in Case 2210 an employee wrote receipts to customers for their purchases, but she removed the carbon-paper backing on the receipts so that they did not produce a company copy. The employee then used a pencil to prepare company copies that showed lower purchase prices. For example, if the customer had paid $100, the company copy might reflect a payment of $80. The employee skimmed the difference between the actual amount of revenue and the amount reflected on the fraudulent receipt. This can also be accomplished at the register when the fraudster underrings a sale, entering a sales total that is lower than the amount actually paid by the customer. The employee skims the difference between the actual purchase price of the item and the sales figure recorded on the register. Rather than reduce the price of an item, an employee might record the sale of fewer items. If 100 units are sold, for instance, a fraudster might only record the sale of 50 units and skim the excess receipts.

Check-for-Currency Substitutions Another common skimming scheme is to take unrecorded checks that the perpetrator has stolen and substitute them for receipted currency. This type of scheme is especially common when the fraudster has access to incoming funds from an unusual source, such as refunds or rebates that have not been accounted for by the victim organization. The benefit of substituting checks for cash, from the fraudster's perspective, is that stolen checks payable to the victim organization may be difficult to convert. They also leave an audit trail showing where the stolen check was deposited. Currency, on the other hand, disappears into the economy once it has been spent.

EXHIBIT 2-6 Understated Sales

An example of a check-for-currency substitution was found in Case 1120, where an employee responsible for receipting ticket and fine payments on behalf of a municipality abused her position and stole incoming revenues for nearly two years. When this individual received payments in currency, she issued receipts, but when checks were received she did not. The check payments were therefore unrecorded revenues—ripe for skimming. These unrecorded checks were then placed in the day's receipts and an equal amount of cash was removed. The receipts matched the amount of money on hand except that payments in currency had been replaced with checks.

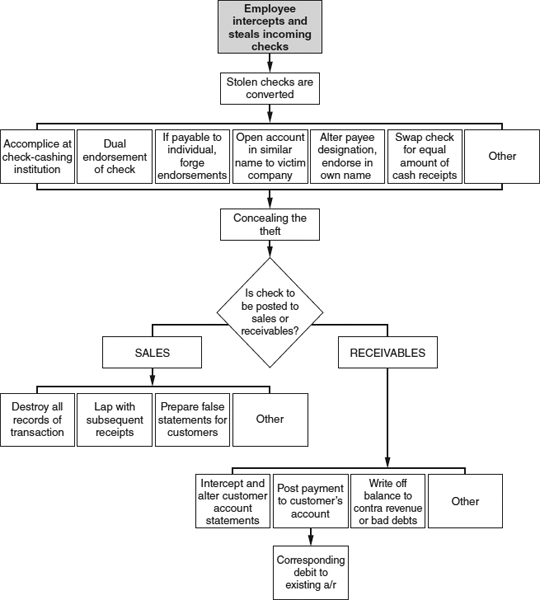

EXHIBIT 2-7 Theft of Incoming Checks

Theft in the Mail Room—Incoming Checks Another common form of skimming occurs in the mailroom, where employees charged with opening the daily mail simply take incoming checks instead of processing them. The stolen payments are not posted to the customer accounts, and from the victim organization's perspective it is as if the check had never arrived (see Exhibit 2-7). When the task of receiving and recording incoming payments is left to a single person, it is all too easy for that employee to slip an occasional check into his pocket.

An example of a check theft scheme occurred in Case 2052, in which a mailroom employee stole over $2 million in government checks arriving through the mail. This employee simply identified and removed envelopes delivered from a government agency that was known to send checks to the company. Using a group of accomplices acting under the names of fictitious persons and companies, this individual was able to launder the checks and divide the proceeds with his cronies.

Preventing and Detecting Sales Skimming Perhaps the biggest key to preventing skimming of any kind is to maintain a viable oversight presence at any point where cash enters an organization. Recall that the second leg of Cressey's fraud triangle involved a perceived opportunity to commit the fraud and get away with it. When an organization establishes an effective oversight presence, it diminishes the perception among employees that they would be able to steal without getting caught. In other words, employees are less likely to try to steal.

Therefore, it is important to have a visible management presence at all cash entry points, including cash registers and the mailroom. This is not to say that a manager must hover over cashiers and mailroom clerks at all times—too much oversight can actually produce a negative effect on employees, causing them to feel mistrusted, possibly making them resentful of management. But managers should routinely check on all cash entry points, not just to look for fraud but also to ensure proper customer service, to monitor productivity, and so forth.

Instead of a physical management presence, video cameras can be installed at cash entry points to serve essentially the same purpose. The principal benefit to the use of video cameras is not that it might detect theft (which it might), but that it might dissuade employees from attempting to steal. Incidentally, a twenty-four-hour video monitoring system can also deter any off-hours sales of the kind that were discussed earlier in this chapter.

Organizations do not have to rely solely on management to oversee cash collections. In retail organizations that utilize several cash registers, the registers are frequently placed in one “cluster” area rather than spread out through the store. One reason for this is so that cashiers will be working in full view of other employees as well as customers. Again, this serves to deter attempts at skimming.

Customers can also be utilized in the monitoring function. Have you ever seen a sign at a retail establishment offering a discount to any customer who does not get a receipt at the time of his purchase? The purpose for these programs is to force employees to ring up sales, thereby making it more difficult to commit an unrecorded sales scheme. In addition, customer complaints and tips are a frequent source of detection for all types of occupational fraud, including skimming. Calls from customers for whom there is no record, for example, are a clear red flag of unrecorded sales. In addition, customer complaints should be received and investigated by employees who are independent of the sales staff.

All cash registers should record the log-in and log-out time of each user. This simple measure makes it easy to detect off-hours sales by comparing log-in times to the organization's hours of operation. In addition, should a theft occur, the user log will be helpful in identifying the potential culprit.

Off-site sales personnel should also be required to maintain activity logs accounting for all sales visits and other business-related activities. These logs should include information such as the customer's name, address and phone number, the date and time of the meeting, and the result of the meeting (e.g., was a sale made?). Employees independent of the sales function can spot-check the veracity of the entries by making “customer satisfaction calls” in which the customer would be asked to verify the information recorded in the activity log.

In addition to monitoring, organizations can take other steps to reduce employees' perceived opportunity to steal. For example, it is advisable, particularly in busy retail establishments, to maintain a secure area where cashiers are required to store coats, hats, purses, and so on. The idea is to eliminate potential hiding places for stolen money.

In the mailroom, employees who open incoming mail should do so in a clear, open area free from blind spots. Preferably there should be a supervisory presence or video monitoring in place when mail is opened, in order to deter thefts. At least two employees should be involved with opening the organization's mail and logging incoming payments, so that one will not be able to steal incoming checks without the other noticing.

Receivables Skimming

Skimming receivables is more difficult than skimming sales. Incoming receivables payments are expected, so the victim organization is likely to notice if these payments are not received and logged into the accounting system. As receivables become past due, the victim organization will send notices of nonpayment to its customers. Customers will complain when they receive a second bill for a payment that has already been made. In addition, the customer's cashed check will serve as evidence that the payment was made.

CASE STUDY: BEVERAGE MAN TAKES THE PLUNGE2

For most people, Florida shines brightly from postcards and televisions, as brilliant as it must have seemed to the first Europeans who hoped to find the Fountain of Youth there. The contemporary image is a little gaudier than ancient myth, but still going strong. And when most people go to Florida, the vacation schedule and the tourist industry can make it seem as if the postcard image lives and breathes.

There really is something for the entire family: a tropical paradise for Mom and Dad, lots of noise and colors for the kiddies. But televisions switch off, and tourists go home. The land remains a place where people work, where they live and breathe and raise their families. This is the story of one of those people.

Stefan Winkler worked for a beverage company in Pompano Beach, Florida. As director of accounting and controller, Stefan touched the flow of money into and out of the company at every point, though he was particularly focused on how money came in. The beverage company—call it Mogel's, Inc.—collected from customers in two ways: either the delivery drivers brought in cash or checks from their route customers, or credit customers sent checks in the mail.

The cash and checks from drivers were counted and put in the bank as route deposits; the checks arriving by mail from credit customers were filed as office deposits. Drivers gave their daily collections to a cashier who made out the route deposit slip and sent it to Stefan Winkler. Any checks from office mail came directly to Winkler, who verified the money according to the payment schedule—thirty days for some customers, sixty for others, and so on. Winkler's job was to combine office deposits and route deposits for the final accounting before bank deposit. Theoretically, then, Mogel's had two revenue streams, both of which converged at Winkler's desk and poured smoothly into the bank.

But Winkler had other plans. He siphoned off the cash from the route deposits through a lapping operation, covering the money he lifted from one account with funds from another. Winkler took large amounts of cash from the route deposits and replaced each cash amount with checks from the credit customers. He might filch $3,000 in cash from the transportation bags and put in $3,000 worth of checks from the mail. That way, the route deposit total matched the amount listed by the cashier on the deposit slip. There was no gap in office deposits, because he never listed the check as received. Instead, he would extend the customer's payment schedule outward, sometimes indefinitely. He occasionally covered the amount later with other embezzlements. Like a kiting operation, lapping takes a continual replenishment of money, forcing the perpetrator to extend the circles of deception wider if the scheme is to continue to produce. And like kiting, lapping is destined to crumble, unless the person can find a way to replace the original funds and casually walk away. Winkler probably told himself he'd replace the money sometime, preferably sooner than later. Maybe he figured he'd make a killing in the stock market or win big at the track and set everything right again. Only he knows what he was thinking; he never admitted to taking anything. Acting as his own lawyer, he announced at trial, “There are other people besides me who could have taken that money.” The prosecution, then, had to prove that Winkler, and not those other people, had actually stolen the money. How that happened is, as they say, the rest of the story. Mogel's operated in Pompano Beach as a subsidiary of a larger company from Delaware. Oversight was casual; auditors generally prepared their reports by dispatches from the local office. This gave Winkler as accounting director lots of room to maneuver. But perhaps there was too much room.

Over the course of a year and a half, Winkler's superiors became increasingly dissatisfied with his performance. Winkler was, fatefully enough, fired on the Friday morning before auditors were to arrive the following Monday. He didn't have the money to replace what he'd stolen, so he used the time to rearrange what he could of his misdealing and throw the rest into disarray. He took cash receipts journals, copies of customer checks, deposit slips, and other financial records from the office and removed his personnel file. He altered electronic files, too, backdating accounts receivable lines to make them current and increasing customer discounts. Examiners would eventually discover “an extremely unusual general ledger adjustment of $303,970.25” made just before Winkler was fired. As the prosecuting attorney, Tony Carriuolo, puts it, “He attempted, through computers and other manipulations, to alter history.”

When the auditors arrived on Monday, they started the long haul of reconstructing what had actually happened. This was, as Carriuolo and certified fraud examiner Don Stine put it, “the fun part, even though it was exhausting, of piecing together what happened and who did it, with documents missing and nothing that we could use to point directly at Winkler and say, ‘There it is, he did it.’” Auditors for Mogel's set about evaluating the mess Winkler had left behind, working through bank statements, total deposit schedules, accounting records, and reports from delivery drivers.

They caught on to Winkler's method during the first efforts to reconstruct the previous two years' activity. An auditor found two checks totaling $60,000 on a route deposit slip, but no entry in the accounts receivable brought forward for that month. (This was for July, a little over a month before Winkler was fired.) The deposit slip, someone pointed out, was not in the cashier's handwriting but Winkler's.

Still, making the case would not be as simple as locating route deposits with checks in them. Some customers paid with checks, and the company's cashier routinely used route money to cash employees' paychecks. Thus, deposits regularly contained checks as well as cash. Examiners would have to cover each deposit and its constituent parts, and compare this against what actually hit the bank and the accounts receivable entries in the office deposits. Carriuolo says, “I can't tell you how many times we had to compare the deposit slips from the cashier—some of which we had, and some we didn't—with the actual composition going to the bank.” Because Winkler had removed so much from the office, sometimes the only way to verify what had come through the mail was to go to customers and reconstruct payments based on their records.

Once the auditors had gone through the material, they hired Don Stine to confirm their findings and help Carriuolo make the case against Winkler. Reviewing their work, Stine agreed that approximately $350,000 had been taken, and that Winkler was the man. Mogel's left themselves wide open for this hit because they had no controls covering what happened with the checks that came in the mail, in effect giving Winkler “total authority” to manipulate the accounts. Stine says that the situation at Mogel's is all too common, with managers and employees not recognizing a financial crime in progress until it's too late. “There are plenty of things to alert people—missing deposit slips, cash and credit reconciliations between a company and a customer that don't match. There are signs, but it doesn't hit them in the head, and then when something comes out, they say, ‘How did this happen?’” Auditors did ask by phone why customers were paying later and later, but they took Winkler's word for it when he put the delays down to computer systems and reorganizations inside the companies.

First contacts with Winkler didn't pan out. He skipped meetings, stonewalled, and acted sullen and defiant. “I didn't do it,” he said. “Trust me. Other people had access, they could have done it, too.” But Stine and Carriuolo were ready for this. Winkler admitted that several clerks and cashiers had worked at Mogel's during a two-year period, but that losses had occurred continually. Unless the company was consistently hiring crooks in those positions, Carriuolo argued, the answer lay elsewhere. Besides, the manipulations required someone with accounting skills above the level of the average clerk. The one constant, it turns out, was Stefan Winkler. Two other workers had actually been there during the entire time period, but they had neither the access nor the skills necessary to redirect cash flow on the scale that had occurred.

And there was the physical evidence. When he came to Mogel's, Winkler was in a bind. He had lost his house, and his finances were a mess. But his tenure at the beverage company brought a wave of prosperity. He bought luxury watches, expensive clothing, and several cars, among them a $40,000 Corvette—paid for in cash. Winkler set up several businesses, including a limousine service, a jewelry distributorship, and facilities for a daycare center he planned to establish with his wife. He spent lots of money gambling, which he used as an explanation for his Rich and Famous mode of living. “I gamble a lot. I win a lot,” he said. “The pit bosses in the Bahamas taught me how to play, so I win almost all the time—simple as that. Just lucky, I guess.” Stine knew this was bunk. Nobody was that lucky, not over two years. Winkler's wave of wealth pushed the “Lifestyle Changes, You Lose” button in the game of fraud examination. “You see this in many of these employee defalcation, or employee fraud, cases,” comments Stine. “Someone is making $50,000 a year, but they're buying a $500,000 home, driving a $75,000 car. And unless someone died and left them an inheritance, it doesn't add up.”

In the civil trial for fraud and negligence, Winkler maintained his innocence—and his arrogance. Carriuolo and Stine presented evidence to show how the route deposits cash had been embezzled and covered for by the office deposits, explaining to the jury with charts and graphs and crash-course accounting presentations what crimes had occurred. The employee records, and the broad authority necessary to pull the scheme off, pointed the finger at Winkler. No one else, Carriuolo maintained, had the “unique access to, and knowledge of Mogel's Inc.'s computerized accounting systems” besides Winkler. Winkler's response? He dismissed (or lost) his attorney and declared he would represent himself. Little or no legal expertise was necessary for his defense: “It wasn't me, it must have been one of those other guys.” When he cross-examined Don Stine, who has twelve years in litigation consulting, Winkler announced he had only one question: “Mr. Stine, do you know for certain who took the money?” Stine answered, “No,” not with absolute, unconditional, onto-logical certainty. Happy to show there was no smoking gun, Winkler rested his case.

But the jury was unconvinced by Winkler's tactics. After a brief recess, they returned a guilty verdict for the $353,000 lost by Mogel's, plus treble damages, for a total judgment of over a million dollars. And it seems that Winkler remains unreconstructed, since he was recently named in a complaint filed by the company he worked for after Mogel's. His high life keeps seeking new lows.

Obviously, receivables skimming schemes are more difficult to conceal than sales skimming schemes. When fraudsters attempt to skim receivables, they generally use one of the following techniques to conceal the thefts:

- Lapping

- Force balancing

- Stolen statements

- Fraudulent write-offs or discounts

- Debiting the wrong account

- Document destruction

Lapping Lapping customer payments is one of the most common methods of concealing receivables skimming. Lapping is the crediting of one account through the abstraction of money from another account. It is the fraudster's version of “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” Suppose a company has three customers: A, B, and C. When A's payment is received, the fraudster takes it for himself instead of posting it to A's account. Customer A expects that his account will be credited with the payment he has made, but this payment has actually been stolen. When A's next statement arrives, he will see that the check was not applied to his account and will complain. To avoid this, some action must be taken to make it appear that the payment was posted.

When B's check arrives, the fraudster takes this money and posts it to A's account. Payments now appear to be up-to-date on A's account, but B's account is short. When C's payment is received, the perpetrator applies it to B's account. This process continues indefinitely until one of three things happens: (1) someone discovers the scheme, (2) restitution is made to the accounts, or (3) some concealing entry is made to adjust the accounts receivable balances.

In the Mogel's case study, we saw that one of the ways Stefan Winkler concealed his thefts was to lap payments on customer accounts. Anecdotal evidence indicates that lapping is perhaps the most common concealment technique for skimming schemes. It should be noted that, though lapping is more commonly used to conceal skimmed receivables, it could also be used to disguise the skimming of sales. In Case 2128, for instance, a store manager stole daily receipts and replaced them with the following day's incoming cash. She progressively delayed making the company's bank deposits as more and more money was taken. Each time a day's receipts were stolen, it took an extra day of collections to cover the missing money. Eventually, the banking irregularities became so great that an investigation was ordered. It was discovered that the manager had stolen nearly $30,000 and had concealed the theft by lapping her store's sales.

Because lapping schemes can become very intricate, fraudsters sometimes keep a second set of books on hand detailing the true nature of the payments received. In many skimming cases, a search of the fraudster's work area will reveal a set of records tracking the actual payments made and how they have been misapplied to conceal the theft. It may seem odd that someone would keep records of his illegal activity on hand, but many lapping schemes become increasingly complicated as more and more payments are misapplied. The second set of records helps the perpetrator keep track of what funds he has stolen and what accounts need to be credited to conceal the fraud. Uncovering these records, if they exist, will greatly aid the investigation of a lapping scheme.

Force Balancing Among the most dangerous receivables skimming schemes are those in which the perpetrator is in charge of collecting and posting payments. If a fraudster has a hand in both ends of the receipting process, he can falsify records to conceal the theft of receivables payments. For example, the fraudster might post an incoming payment to a customer's receivables account, even though the payment will never be deposited. This keeps the receivable from aging, but it creates an imbalance in the cash account. The perpetrator hides the imbalance by forcing the total on the cash account, overstating it to match the total postings to accounts receivable.

Stolen Statements Another method used by employees to conceal the misapplication of customer payments is the theft or alteration of account statements. If a customer's payments are stolen and not posted, his account will become delinquent. When this happens, he should receive late notices or statements that show that his account is past due. The purpose of altering a customer's statements is to keep him from complaining about the misapplication of his payments.

To keep a customer unaware about the true status of his account, some fraudsters will intercept his account statements or late notices; this might be accomplished, for example, by changing the customer's address in the billing system. The statements will be sent directly to the employee's home, or to an address where he can retrieve them. In other cases, the address is changed so that the statement is undeliverable, which causes the statements to be returned to the fraudster's desk. In either situation, once the employee has access to the statements, he can do one of two things.

The first option is to throw the statements away, but this will not be particularly effective if the customer ever requests information about his account after not having received a statement.

Therefore, the fraudster may instead choose to alter the statements, or to produce counterfeit statements to make it appear that the customer's payments have been properly posted. The fraudster then sends these fake statements to the customer. The false statements lead the customer to believe that his account is up to date, keeping him from complaining about stolen payments.

Fraudulent Write-Offs or Discounts Intercepting the customer's statements will keep him in the dark as to the status of his account, but the problem still remains: as long as the customer's payments are being skimmed, his account is slipping further and further past due. The fraudster must find some way to bring the account back up to date in order to conceal his crime. As we have discussed, lapping is one way to keep accounts current as the employee skims from them. Another way is to fraudulently write off the customer's account. In Case 2435, for example, an employee skimmed cash collections and wrote off the related receivables as “bad debts.” Similarly, in Case 442, a billing manager was authorized to write off certain patient balances as hardship allowances. This employee accepted payments from patients and then instructed billing personnel to write off the balance in question. The payments were never posted, because the billing manager intercepted them. She covered approximately $30,000 in stolen funds by using her authority to write off patients' account balances.

Instead of writing off accounts as bad debts, some employees cover their skimming by posting entries to contra revenue accounts such as “discounts and allowances.” If, for instance, an employee intercepts a $1,000 payment, he would create a $1,000 “discount” on the account to compensate for the missing money.

Debiting the Wrong Account Fraudsters might also debit existing or fictitious accounts receivable in order to conceal skimmed cash. In Case 1996, for example, an office manager in a health care facility took payments from patients for herself. To conceal her activity, the office manager added the amounts taken to the accounts of other patients that she knew would soon be written off as uncollectable. The employees who use this method generally add the skimmed balances to accounts that either are very large or that are aging and about to be written off. Increases in the balances of these accounts are not as noticeable as in other accounts. In the case above, once the old accounts were written off, the stolen funds would be written off along with them.

Rather than using existing accounts, some fraudsters set up completely fictitious accounts and debit them for the cost of skimmed receivables. The employees then simply wait for the fictitious receivables to age and be written off, knowing that they are uncollectable. In the meantime, they carry the cost of a skimming scheme where it will not be detected.

Destroying or Altering Records of the Transaction Finally, when all else fails, a perpetrator may simply destroy an organization's accounting records in order to cover his tracks. For instance, we have already discussed the need for a salesperson to destroy the store's copy of a receipt in order for the sale to go undetected. Similarly, cash register tapes may be destroyed to hide an off-book sale. In Case 788, two management-level employees skimmed approximately $250,000 from their company over a four-year period. These employees tampered with cash register tapes that reflected transactions in which sales revenues had been skimmed. The perpetrators either destroyed entire register tapes or cut off large portions where the fraudulent transactions were recorded. In some circumstances, the employees then fabricated new tapes to match the cash on hand and make their registers appear to balance.

Discarding transaction records is often a last-ditch method for a fraudster to escape detection; the fact that records have been destroyed may itself signal that fraud has occurred. Nevertheless, without the records it can be very difficult to reconstruct the missing transactions and prove that someone actually skimmed money. Furthermore, it may be difficult to prove who was involved in the scheme.

Preventing and Detecting Receivables Skimming Receivables skimming schemes typically succeed when there is a breakdown in an organization's controls, particularly when one individual has too much control over the process of receiving and recording customer payments, posting cash receipts, and issuing customer payments. If the accounting duties associated with accounts receivable are properly separated so that there are independent checks of all transactions, skimming of these payments is very difficult to commit and very easy to detect. For example, when force balancing is used to conceal skimming of receivables, it causes a shortage in the organization's cash account, since incoming payments are received but never deposited. By simply reconciling its bank statement regularly and thoroughly, an organization ought to be able to catch this type of fraud. Similarly, when an individual skims receivables but continues to post the payments to customer accounts, postings to accounts receivable will exceed what is reflected in the daily deposit. If an organization assigns an employee to independently verify that deposits match accounts receivable postings, this type of scheme ought to be quickly detected—or, more likely, will not be attempted at all. It is also a good idea to have that employee spot-check deposits to accounts receivable to ensure that payments are being applied to the proper accounts. If a check were received by Customer A but the payment posted to Customer B's account, this would indicate a lapping scheme.

As was discussed earlier, lapping schemes can become very complicated and may require the perpetrator to spend long hours at work trying to shift funds around in order to conceal the crime. Ironically, it is very common in these cases for the perpetrator to actually develop a reputation as a model employee because of all the overtime he puts in at the office. After the frauds come to light, the employers frequently express shock not only because they were defrauded, but also because they had considered the perpetrator to be one of their best employees. The point is that a lapping scheme can only succeed through the constant vigilance of the perpetrator. Because of this fact, many organizations mandate that their employees take a vacation every year, or regularly rotate job duties among employees. Both of these tactics can be successful in uncovering lapping schemes, because they effectively take control of the books out of the perpetrator's hands for a period of time; when this happens, the lapping scheme will quickly become apparent.

It is also important to mandate supervisory approval for write-offs or discounts to accounts receivable. As we have seen, fraudulent write-offs and discounts are a common means by which receivables skimming is concealed; they enable the fraudster to wipe the stolen funds off the books. However, if the person who receives and records customer payments has no authority to make these adjustments, then the perceived opportunity to commit the crime is severely diminished.

While strong internal controls are a valuable preventative tool, the fact remains that fraud can and will continue to occur, regardless of the existence of controls designed to prevent it. Organizations must also be able to detect fraud once it has occurred. Some detection methods are very simple. For example, fraudsters sometimes conceal the theft of receivables by making alterations or corrections to books and records. Physical alterations to financial records, such as erasures or cross-outs, are often a sign of fraud, as are irregular entries to miscellaneous accounts. Audit staff should be trained to investigate these red flags.

It is also important for organizations to proactively search out accounting clues that point to fraud. This can be tedious, time-consuming work, but computerized audit tools allow organizations to automate many of these tests and greatly aid in the process of searching out fraudulent conduct.

The key to successfully using automated tests is in designing them to highlight the red flags typically associated with a particular scheme. For example, we have seen that fraudsters often conceal the skimming of receivables by writing off the amount of funds they have stolen from the targeted account. To detect this kind of activity, organizations can run reports summarizing the number of discounts, adjustments, returns, write-offs, and so on, generated by location, department, or employee. Unusually high levels may be associated with skimming schemes and could warrant further investigation. Because some fraudsters conceal their skimming by debiting accounts that are aging or that typically have very little activity, it may also be helpful to run reports looking for unusual activity in otherwise dormant accounts.

Trend analysis on aging of customer accounts can likewise be used to highlight a skimming scheme. A significant rise in the number or size of overdue accounts could be a result of an employee's having stolen customer payments without ever posting them, thereby causing the accounts to run past due. If skimming is suspected, an employee who is independent of the accounts receivable function should confirm overdue balances with customers.

There are several audit tests that can be used to help detect various forms of occupational fraud. In each chapter of this book where fraud schemes are examined, we will provide a set of proactive computer audit tests that are tailored to that particular category of fraud. These tests were developed and accumulated by Richard Lanza, working through the Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation.2

PROACTIVE COMPUTER AUDIT TESTS DETECTING SKIMMING3

SUMMARY

Skimming is defined as the removal of cash from an organization prior to its entry into the books and records. Most skimming schemes follow the same basic pattern: an employee steals incoming funds before they are recorded by the victim organization. These schemes can be subdivided based on whether they involve the theft of sales or receivables. The character of the incoming funds affects how the frauds are concealed, which is the key to sustaining an occupational fraud scheme.

Because skimming schemes are off-book frauds, they leave no direct audit trail. This can make it difficult for victim organizations to detect that cash has been stolen, let alone detect who committed the crime.

The most basic skimming scheme involves the unrecorded sale of goods. There are a number of variations of sales skimming. These include register manipulations, after-hours sales, skimming by off-site employees, understated sales, check-for-currency substitutions, and theft of incoming checks received through the mail.

Receivables skimming is more difficult than sales skimming, because the payments that are stolen are expected by the victim organization. In order to succeed at a receivables skimming scheme, the perpetrator must conceal the thefts from the victim organization and, in many cases, from the customer whose payment was stolen. Receivables skimming is generally concealed by one of the following methods: lapping, force balancing, stolen statements, fraudulent write-offs or discounts, debits to the wrong account, or document destruction.

ESSENTIAL TERMS

Skimming Theft of cash prior to its entry into the accounting system.

Sales skimming Skimming that involves the theft of sales receipts, as opposed to payments on accounts receivable. Sales skimming schemes leave the victim organization's books in balance, because neither the sales transaction nor the stolen funds are ever recorded.

Off-book fraud A fraud that occurs outside the financial system and therefore has no direct audit trail. There are several kinds of off-book frauds that will be discussed in this book. Skimming is the most common off-book fraud.

Understated sales A variation of a sales skimming scheme in which only a portion of the cash received in a sales transaction is stolen. This type of fraud is not off-book, because the transaction is posted to the victim organization's books but for a lower amount than the perpetrator collected from the customer.

Check-for-currency substitution A skimming method whereby the fraudster steals an unrecorded check and substitutes it for recorded currency in the same amount.

Receivables skimming Skimming that involves the theft of incoming payments on accounts receivable. This form of skimming is more difficult to detect than sales skimming, because the receivables are already recorded on the victim organization's books. In other words, the incoming payments are expected by the victim organization. The key to a receivables skimming scheme is to conceal either that the payment was stolen or that the payment was due.

Lapping A method of concealing the theft of cash designated for accounts receivable by crediting one account while abstracting money from a different account. This process must be continuously repeated to avoid detection.

Force balancing A method of concealing receivables skimming whereby the fraudster falsifies account totals to conceal the theft of funds. This is also sometimes known as “plugging.” Typically, the fraudster will steal a customer's payment but nevertheless post it to the customer's account so that the account does not age past due. This causes an imbalance in the cash account.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

2-1 (Learning objective 2-1) How is “skimming” defined?

2-2 (Learning objective 2-2) What are the two principal categories of skimming?

2-3 (Learning objective 2-3) How do sales skimming schemes leave a victim organization's books in balance, despite the theft of funds? the theft of funds?

2-4 (Learning objective 2-3) Under what circumstances are incoming checks that are received through the mail typically stolen?

2-5 (Learning objective 2-4) How do “understated sales” schemes differ from “unrecorded sales”?

2-6 (Learning objective 2-5) How is the cash register manipulated to conceal skimming?

2-7 (Learning objective 2-6) Give examples of both skimming during nonbusiness hours and skimming of off-site sales.

2-8 (Learning objective 2-8) What are the six principal methods used to conceal receivables skimming?

2-9 (Learning objective 2-9) What is “lapping,” and how is it used to conceal receivables skimming?

2-10 (Learning objective 2-10) List four types of false entries a fraudster can make in the victim organization's books to conceal receivables skimming.

DISCUSSION ISSUES

2-1 (Learning objective 2-3) Sales skimming is called an “off-book” fraud. Why?

2-2 (Learning objective 2-3) In the case study of Brian Lee, the plastic surgeon, what kind of skimming scheme did he commit?

2-3 (Learning objectives 2-5 and 2-12) If you suspected skimming of sales at the cash register, what is one of the first things you would check?

2-4 (Learning objective 2-3) Assume that a client who owns a small apartment complex in a different city than where he lives has discovered that the apartment manager has been skimming rental receipts, which are usually paid by check. The manager endorsed the checks with the apartment rental stamp, then endorsed her own name and deposited the proceeds into her own checking account. Because of the size of the operation, hiring a separate employee to keep the books is not practical. How could a scheme like this be prevented in the future?

2-5 (Learning objectives 2-8 and 2-11) What is the most effective control to prevent receivables skimming?

2-6 (Learning objectives 2-3 and 2-7) In many cases involving skimming, employees steal checks from the incoming mail. What are some of the controls that can prevent such occurrences?

2-7 (Learning objectives 2-7 and 2-11) In the case study of Stefan Winkler, chief financial officer for a beverage company in Florida, how did he conceal his skimming scheme? How could the scheme have been prevented or discovered?

ENDNOTES

1Several names and details have been changed to preserve anonymity.

1. Throughout the text, numbered case examples are provided to illustrate the various occupational fraud schemes. These examples are derived from responses to ACFE Fraud Surveys.

2Some names have been changed to preserve anonymity.

2. Richard B. Lanza, CPA, PMP, Copyright 2003, Proactively Detecting Occupational Fraud Using Computer Audit Reports, by The Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation, 247 Maitland Avenue, Altamonte Springs, Florida 32701-4201 U.S.A. Reprinted with permission.

3. Lanza, pp. 41–44.