EXHIBIT 12-1

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

| 12-1 | Define financial statement fraud and related schemes |

| 12-2 | Understand and identify the five classifications of financial statement fraud |

| 12-3 | Explain how fictitious revenues schemes are committed, as well as the motivation for, and result of, committing such fraud |

| 12-4 | Explain how timing difference schemes are committed, as well as the motivation for, and result of, committing such fraud |

| 12-5 | Describe the methods by which concealed liabilities and expenses are used to fraudulently improve a company's balance sheet |

| 12-6 | Understand how improper disclosures may be used to mislead potential investors, creditors, or other users of the financial statements |

| 12-7 | Recognize how improper asset valuation may inflate the current ratio |

| 12-8 | Identify detection and deterrence procedures that may be instrumental in dealing with fraudulent financial statement schemes |

| 12-9 | Understand financial statement analysis for detecting fraud |

| 12-10 | Identify and characterize current professional and legislative actions that have sought to improve corporate governance, enhance the reliability and quality of financial reports, and foster credibility and effectiveness of audit functions |

CASE STUDY: THAT WAY LIES MADNESS1

“I'm Crazy Eddie!” a goggle-eyed man screams from the television set, pulling at his face with his hands. “My prices are in-sane!” Eddie Antar got into the electronics business in 1969, with a modest store called Sight and Sound. Less than twenty years later, he had become Crazy Eddie, a millionaire many times over and an international fugitive from justice. He was shrewd, daring, and self-serving; he was obsessive and greedy. But he was hardly insane. A U.S. Attorney said, “He was not Crazy Eddie. He was Crooked Eddie.”

The man on the screen wasn't Eddie at all. The face so dutifully watched throughout New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut—that was an actor, hired to do a humiliating but effective characterization. The real Eddie Antar was not the kind of man to yell and rend his clothes. He was busy making money, and he was making a lot of it illegally. By the time his electronics empire folded, Antar and members of his family had distinguished themselves with a fraud of massive proportions, reaping more than $120 million. A senior official at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) quipped, “This may not be the biggest stock fraud of all time, but for outrageousness it is going to be very hard to beat.” The SEC was joined by the FBI, the Postal Inspection Service, and the U.S. Attorney in tracking Eddie down. They were able to show a multipronged fraud in which Antar:

- Listed smuggled money from foreign banks as sales

- Made false entries to accounts payable

- Overstated Crazy Eddie, Inc.'s inventory by breaking into and altering audit records

- Took credit for merchandise as “returned” while also counting it as inventory

- “Shared” inventory from one store to boost other stores' audit counts

- Arranged for vendors to ship merchandise and defer the billing, besides claiming discounts and advertising credits

- Sold large lots of merchandise to wholesalers, then spread the money to individual stores as retail receipts

It was a long list, and a profitable one for Eddie Antar and the inner circle of his family. The seven action items were designed to make Crazy Eddie's look like it was booming. In fact, it was. It was the single biggest retailer of stereos and televisions in the New York metropolitan area, with a dominant and seemingly impregnable share of the market. But that wasn't enough for Eddie. He took the chain public, and then made some real money. Shares that initially sold at $8 each later peaked at $80, thanks to the Antar team's masterful tweaking of company accounts.

Inflating Crazy Eddie's stock price wasn't the first scam Antar had pulled. In the early days, as Sight and Sound grew into Crazy Eddie's and spawned multiple stores, Eddie was actually underreporting his earnings. Eddie's cousin, Sam Antar, remembered learning how the company did business by watching his father during the early days. “The store managers would drop off cash to the house after they closed at ten o'clock, and my father would make one bundle for deposit into the company account, and several bundles for others in the family,” Sam Antar said. “Then he would drive over to their houses and drop off their bundles at two in the morning.” For every few dollars to the company, the Antars took a dollar for themselves. The cash was secreted away into bank accounts at Bank Leumi of Israel. Eddie smuggled some of the money out of the country himself, by strapping stacks of large bills across his body. The Antars sneaked away with at least $7 million over several years. Skimming the cash meant tax-free profits, and one gargantuan nest egg waiting across the sea.

But entering the stock market was another story. Eddie anticipated the initial public offering (IPO) of shares by quietly easing money from Bank Leumi back into the operation. The company really was growing, but injecting the pilfered funds as sales receipts made the growth look even more impressive: Skim the money and beat the tax man, then draw out funds as you need them to boost sales figures. Keeps the ship running smooth and sunny.

But Paul Hayes, a special agent who worked the case with the FBI, pointed out Crazy Eddie's problem. “After building up the books, they set a pattern of double-digit growth, which they had to sustain. When they couldn't sustain it, they started looking for new ways to fake it,” Hayes said.

Eddie, his brothers, his cousins, and several family loyalists all owned large chunks of company stock. No matter what actually happened at the stores, they wanted that stock to rise. So the seven-point plan was born. There was the skimmed money waiting overseas, being brought back and disguised as sales. But there were limits to how much cash the family had available and could get back into the country, so they turned to other methods of inflating the company's financials. In the most daring part of the expanded scam, Antar's people broke into auditors' records and boosted the inventory numbers. With the stroke of a pen, 13 microcassette players became 1,327.

Better than that, the Antars figured out how to make their inventory do double work. Debit memos were drawn up showing substantial lots of stereos or VCRs as “returned to manufacturer.” Crazy Eddie's was given a credit for the wholesale cost due back from the manufacturer. But the machines were kept at the warehouse to be counted as inventory. In a variation of the inventory scam, at least one wholesaler agreed to ship Crazy Eddie truckloads of merchandise, deferring the billing to a later date. That way Crazy Eddie's had plenty of inventory volume, plus the return credits listed on the account book. And what if auditors got too close and began asking questions? Executives would throw the records away. A “lost” report was a safe report.

Eddie Antar didn't stop at simple bookkeeping and warehouse games; he “shared inventory” among his nearly forty stores. After auditors had finished counting a warehouse's holdings and had gone for the day, workers tossed the merchandise into trucks. The inventory was hauled overnight to an early morning load-in at another store. When the auditors arrived at that store, they found a full stockroom waiting to be counted. Again, this ruse carried a double payoff. The audit looked strong because of the inventory items counted multiple times, and the bookkeeping looked good because only one set of invoices was entered as payable to Eddie's creditors. Also, the game could be repeated for as long as the audit route demanded.

Eddie's trump card was the supplier network. He had considerable leverage with area wholesalers, because Crazy Eddie's was the biggest and baddest retail outlet in the region. Agent Paul Hayes remembers Eddie as “an aggressive businessman: He'd put the squeeze on a manufacturer and tell them he wasn't going to carry their product. Now, he was king of what is possibly the biggest consolidated retail market in the nation. Japanese manufacturers were fighting each other to get into this market . . . So when Eddie made a threat, that was a threat with serious potential impact.”

Suppliers gave Crazy Eddie's buyers extraordinary discounts and advertising rebates. If they didn't, the Antars had another method: They made up the discount. For example, Crazy Eddie's might owe George-Electronics $1 million: by claiming $500,000 in discounts or ad credits, the bill was cut in half. Sometimes there was a real discount, sometimes there wasn't. (It wasn't easy, after Eddie's fall, to tell what was a shrewd business deal and what was fraud. “They had legitimate discounts in there,” says Hayes, “along with the criminal acts. That's why it was tough to know what was smoke and what was fire.”)

Eddie had yet another arrangement with manufacturers. For certain high-demand items—high-end stereo systems, for example—a producing company would agree to sell only to Crazy Eddie. Eddie placed an order big enough for what he needed and then added a little more. The excess he sold to a distributor who had already agreed to send the merchandise outside Crazy Eddie's tristate area. And then the really good part: By arrangement, the distributor paid for the merchandise in a series of small checks—$100,000 worth of portable stereos would be paid off with 10 checks of $10,000 each. Eddie sprinkled this money into his stores as register sales. He knew that Wall Street analysts use comparable store sales as a bedrock indicator. New stores are compared with old stores, and any store open more than a year is compared with its performance during the previous term. The goal is to outperform the previous year. So the $10,000 injections made Eddie's “comps” look fantastic.

As the doctored numbers circulated in enthusiastic financial circles, CRZY stock doubled its earnings per share during its first year on the stock exchange. The stock split two-for-one in both of its first two fiscal terms as a publicly traded company. As chairman and chief executive, Eddie Antar used his newsletter to trumpet soaring profits, declining overhead costs, and a new 210,000-square-foot corporate headquarters. Plans were underway for a home-shopping arm of the business. Besides the electronics stores, there was now a subsidiary, Crazy Eddie Record and Tape Asylums, in the Antar fold. At its peak, the operation included forty-three stores and reported sales of $350 million a year. This was a long way from the Sight and Sound storefront operation where it all began.

It was almost eerie how deliberately the Antar conspirators manipulated investors and how directly their crimes affected brokers' assessments. At the end of Crazy Eddie's second public year, a major brokerage firm issued a gushing recommendation to “buy.” The recommendation was explicitly “based on 35 percent EPS [earnings per share] growth” and “comparable store sales growth in the low double-digit range.” These double-digit expansions were from the “comps” that Eddie and his gang had cooked up with wholesalers' money and by juggling inventories. CRZY stock, the report predicted, would double and then some during the next year. As if following an Antar script, the brokers declared, “Crazy Eddie is the only retailer in our universe that has not reported a disappointing quarter in the last two years. We do not believe that is an accident . . . We believe Crazy Eddie is becoming the kind of company that can continually produce above-average comparable store sales growth.” The brokers could not have known what Herculean efforts were needed to yield just that impression. The report praised Eddie's management skills. “Mr. Antar has created a strong organization beneath him that is close-knit and directed . . . Despite the boisterous (less charitable commentators would say obnoxious) quality of the commercials, Crazy Eddie management is quite conservative.”

Well, yes, in a manner of speaking. They were certainly holding tightly to the money as it flowed through the market. According to federal indictments, the conspiracy inflated the company's value during the first year by about $2 million. By selling off shares of the overvalued stock, the partners pocketed over $28.2 million. The next year they illegally boosted income by $5.5 million and retail sales by $2.2 million. This time the group cashed in their stock for a cool $42.2 million windfall. In the last year before the boom went bust, Eddie and his partners inflated income by $37.5 million and retail by $18 million. They didn't have that much stock left, though, so despite the big blowup they only cashed in for about $8.3 million.

Maybe he knew the end was at hand, but with takeovers looming, Eddie kept fighting. He had started his business with one store in Brooklyn almost twenty years before, near the neighborhood where he grew up, populated mainly by Jewish immigrants from Syria. Despite these humble beginnings he would one day be called “the Darth Vader of capitalism” by a prosecuting attorney, referring not just to his professional inveigling but to his personal life as well. Eddie's affair with another woman broke up his marriage and precipitated a lifelong break with his father. Eventually he divorced his wife and married his lover. Rumors hinted that Eddie had been unhappy because he had five daughters and no sons from his first marriage. Neighbors said the rest of the family sided with the ex-wife. Eddie and his brothers continued in business together, but they had no contact outside the company. Allen Antar, a few years younger, should have been able to sympathize—he had also been estranged from the family when he filed for a divorce and married a woman who wasn't Jewish. (Allen eventually divorced that woman and remarried his first wife.) Later at trial, the brothers Antar were notably cold to one another. Even Eddie's own lawyer called him a “huckster.”

But this Darth Vader had a compassionate side. Eddie was known as a quiet man, and modest. He was seldom photographed and almost never granted interviews. He was said to have waited hours at the bedside of a dying cousin, Mort Gindi, whose brother, also named Eddie, was named as a defendant in the Antars' federal trial. His cousin Sam remembers him as “a leader, someone I looked up to since I was a kid. Eddie was strong, he worked out with weights; when the Italian kids wanted to come into our neighborhood and beat up on the Jewish kids, Eddie would stop them. That was when we were kids. Later, it turned out different.”

Eddie had come a long way. He had realized millions of dollars by selling off company stock at inflated prices. This money was stashed in secret accounts around the world, held under various assumed identities. In fact, Eddie had done so well that he was left vulnerable as leader of the retail empire. When Elias Zinn, a Houston businessman, joined with the Oppenheimer-Palmieri Fund and waged a proxy battle for Crazy Eddie's, the Antars had too little shareholders' power to stave off the bid. They lost. For the first time, Crazy Eddie's was out of Eddie's hands.

The new owners didn't have long to celebrate. They discovered that their ship was sinking fast. Stores were alarmingly understocked, shareholders were suing, and suppliers were shutting down credit lines because they were being paid either late or not at all. An initial review showed the company's inventory had been overstated by $65 million—a number later raised to over $80 million. In a desperate maneuver, the new management set up a computerized inventory system and established lines of credit. They made peace with the vendors and cut 150 jobs to reduce overhead. But it was too late. Less than a year after the takeover, Crazy Eddie's was dead.

Eddie Antar, on the other hand, was very much alive. But nobody knew where. He had disappeared when it became apparent that the takeover was forcing him out. He had set up dummy companies in Liberia, Gibraltar, and Panama, along with well-supplied bank accounts in Israel and Switzerland. Sensing that his days as Crazy Eddie were numbered, he fled the United States, traveling the world with faked passports, calling himself, at different times, Harry Page Shalom and David Cohen. Shalom was a real person, a longtime friend of Eddie's, another in a string of chagrined and erstwhile companions.

It was as David Cohen that Eddie ended his flight from justice and reality. After twenty-eight months on the run, he stalked into a police station in Bern, Switzerland—but not to turn himself in. “David Cohen” was demanding help from the police. He was mad because bank officials refused to let him at the $32 million he had on account there. The bank wouldn't tell Cohen anything—just that he couldn't access those funds. But officials discreetly informed police that the money had been frozen by the U.S. Department of Justice. Affidavits in the investigation had targeted the account as an Antar line. It didn't take long to realize that David Cohen, the irate millionaire in the Bern police station, was Eddie Antar. It was the last public part Crazy Eddie would play for a while. He eventually pled guilty to racketeering and conspiracy charges and was sentenced to eight-two months in prison with credit for time served. This left him with about three and a half years of jail time. He was also ordered to repay $121 million to bilked investors. Almost $72 million was recovered from Eddie's personal accounts. “I don't ask for mercy,” Eddie told the judge at his trial. “I ask for balance.”

Eddie's brother, Mitchell, was first convicted and given four-and-a-half years, with $3 million in restitution burdens, but his conviction was overturned because of a prejudicial remark by the judge in the first trial. Mitchell later pled guilty to two counts of securities fraud, and the rest of the charges were dropped. Allen Antar was acquitted at the first trial, but he and his father, Sam, were both later found guilty of insider trading and ordered to pay $11.9 million and $57.5 million, respectively, in disgorgement and interest.

What happened to the Crazy Eddie stores? In 1998, Eddie's nephews attempted to revive the legacy and held a grand opening for a new electronics store in New Jersey. At the beginning of the new millennium, the store's doors closed and Crazy Eddie shifted focus to become a dotcom retailer. But by 2004, the company had once again faltered and closed, this time amid allegations that it had resold unauthorized products online.

OVERVIEW

Financial statement fraud has been a hot subject in the press for many years, and it does not appear to be slowing down anytime soon. High-profile scandals have challenged the corporate responsibility and integrity of major companies, prompting U.S. legislation such as the Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Financial statement fraud isn't limited to the United States, however. In 2009, the chairman of a leading Indian outsourcing company, Satyam Computer Services, revealed significant financial statement fraud had been taking place for the past several years. He claimed that the company's assets were inflated by $1.04 billion and revenues were overstated by 20 percent. In 2011, newly appointed CEO of Olympus Corporation in Japan, Michael Woodford, exposed one of the biggest and longest-running accounting frauds in Japanese corporate history. Woodford was fired from the company less than two months after becoming CEO for questioning the company's accounting practices. For one, a scheme was set up to conceal $1.7 billion in investment losses, and almost $700 million in M&A fees were paid to the company's financial advisors.

It wasn't too long ago that companies, including Sunbeam, Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, Adelphia, Qwest, Tyco, HealthSouth, and AIG, also graced the headlines for fraudulently misstating their financial position. Top management teams, including chief executive officers (CEOs) and chief financial officers (CFOs), of these companies, and of many more, have been accused of cooking the books. Ongoing occurrences of financial statement fraud by high-profile companies have raised concerns about the integrity, transparency, and reliability of the financial reporting process and have challenged the role of corporate governance and audit functions in deterring and detecting financial statement fraud.

DEFINING FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD

The definition of financial statement fraud can be found in a number of authoritative reports (e.g., The Treadway Commission's Report of the National Commission on Fraudulent Financial Reporting (1987) and the AICPA's Statement on Auditing Standards No. 99 (henceforth referred to as the Generally Accepted Auditing Standard AU 240, “Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit”). Financial statement fraud is defined as deliberate misstatements or omissions of amounts or disclosures of financial statements to deceive financial statement users, particularly investors and creditors. Financial statement fraud may involve the following schemes:

- Falsification, alteration, or manipulation of material financial records, supporting documents, or business transactions

- Material intentional omissions or misrepresentations of events, transactions, accounts, or other significant information from which financial statements are prepared

- Deliberate misapplication of accounting principles, policies, and procedures used to measure, recognize, report, and disclose economic events and business transactions

- Intentional omissions of disclosures or presentation of inadequate disclosures regarding accounting principles and policies and related financial amounts (Rezaee 2002)

Generally Accepted Auditing Standard AU 240, entitled “Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit,” issued by the Auditing Standards Board (ASB) of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), defines two types of misstatements relevant to an audit of financial statements and auditors' consideration of fraud (AICPA 2012). The first type is misstatements arising from fraudulent financial reporting, which are defined as “intentional misstatements, including omissions of amounts or disclosures in financial statements to deceive financial statement users” (AICPA 2012). The second type is misstatements arising from misappropriation of assets, which are commonly referred to as theft or defalcation. The primary focus of this chapter is on misstatements arising from fraudulent reporting that directly causes financial reports to be misleading and deceptive to investors and creditors. Fraudulent financial statements can be used to unjustifiably sell stock, obtain loans or trade credit, and/or improve managerial compensation and bonuses. The important issues addressed in this chapter are how to effectively and efficiently deter, detect, and correct financial statement fraud.

COSTS OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD

Published statistics on the possible costs of financial statement fraud—including those from the 2011 Global Fraud Survey that were included in the previous chapter—are estimates, at best. It is impossible to determine the actual total costs because not all fraud is detected, not all detected fraud is reported, and not all reported fraud is legally pursued. Nonetheless, it is safe to say that the full impact of financial statement fraud is astonishing. In addition to the direct economic losses resulting from such manipulations are legal costs; increased insurance costs; loss of productivity; adverse impacts on employees' morale, customers' goodwill, and suppliers' trust; and negative stock market reactions. Another important indirect cost of financial statement fraud is the loss of productivity due to dismissal of the fraudsters and their replacements. While these indirect costs cannot possibly be estimated, they should be taken into consideration when assessing the consequences of financial statement fraud. Loss of public confidence in quality and reliability of financial statements caused by the alleged fraudulent activities is the most damaging and costly effect of fraud.

Financial statement fraud is harmful in many ways. It:

- Undermines the reliability, quality, transparency, and integrity of the financial reporting process. Executives at Beazer Homes USA (Beazer), a former Fortune 500 company located in Charlotte, North Carolina, encouraged the manipulation of corporate earnings to meet financial goals. In this fraud, Beazer executives manipulated the company's financial statements by reducing net income during strong financial periods and providing it with excess balances and reserves, allowing it to “smooth earnings” during times of underperformance. In 2009, Beazer entered into a deferred prosecution agreement, acknowledging culpability, and agreed to pay restitution of $50 million. In 2009, General Electric (GE) agreed to pay a $50 million fine to the SEC to settle charges that it misled investors through fraudulent accounting practices in 2002 and 2003. Prior to the 2009 settlement, GE had already restated some of its financial statements for the years 2001 through 2008. In the wake of scandals such as those involving General Electric, Enron, WorldCom, Adelphia, and Tyco, these types of high-profile financial restatements and enforcement actions by the SEC against big corporations for alleged financial statement fraud severely undermine public confidence in the veracity of financial reports.

- Jeopardizes the integrity and objectivity of the auditing profession, especially of auditors and auditing firms. Auditing firms are considered “public watchdogs.” They are tasked with determining whether clients' financial statements are free of material misstatement, whether due to error or fraud. When a large-scale fraud happens under the watchful eye of an auditor, however, the auditor's credibility is shattered. Arthur Andersen, one of the former “Big Five” CPA firms, dismantled its international network and allowed officers to join rival firms after it became embroiled in a scandal involving its shredding of documents related to its audit work for Enron. Although the Supreme Court ultimately overturned Andersen's conviction for obstruction of justice, the accounting firm had already irreparably crumbled in the wake of the document destruction debacle.

- Diminishes the confidence of the capital markets, as well as market participants, in the reliability of financial information. The capital market and market participants, including investors, creditors, employees, and pensioners, are affected by the quality and transparency of financial information they use in making investment decisions.

- Makes the capital markets less efficient. Auditors reduce the information risk that may be associated with the published financial statements and thus make them more transparent. The information risk is the likelihood that financial statements are inaccurate, false, misleading, biased, and deceptive. By applying the same financial standards to diverse businesses and by reducing the information risk, accountants contribute to the efficiency of our capital markets.

- Adversely affects the nation's economic growth and prosperity. Accountants are expected to make financial statements among corporations more comparable by applying the same set of accounting standards to diverse businesses. This enhanced comparability makes business more transparent, the capital markets more efficient, the free enterprise system possible, and the economy more vibrant and prosperous. The efficiency of our capital markets depends on receiving objective, reliable, and transparent financial information. Thus, the accounting profession, especially practicing auditors, plays an important role in our free enterprise system and capital markets. However, many of the recent accounting scandals provide evidence that the role of accountants can be compromised.

- Results in huge litigation costs. Corporations and their auditors are being sued for alleged financial statement fraud and related audit failures by a diverse group of litigants including small investors in class action suits and the U.S. Justice Department. Investors are also given the right to sue and recover damages from those who aided and abetted securities fraud.

- Destroys careers of individuals involved in financial statement fraud. In 2011, the former chief accounting officer of Beazer Homes was convicted on seven of eleven counts of fraud for the use of false information to finance and sell homes and to manipulate corporate earnings. Top executives are being held personally accountable for the integrity of their company's financial statements. Convicted fraudsters are barred from serving on the boards of directors of any public companies, and auditors are being barred from the practice of public accounting.

- Causes bankruptcy or substantial economic losses by the company engaged in financial statement fraud. WorldCom and Enron make up two of the ten largest bankruptcies in U.S. history. Total assets at the time of filing were $104 billion for WorldCom and $66 billion for Enron.

- Encourages regulatory intervention. Regulatory agencies (e.g., the SEC) considerably influence the financial reporting process and related audit functions. Past perceived crises in the financial reporting process and audit functions ultimately encouraged lawmakers to establish accounting reform legislation in the form of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act. This Act was intended to drastically change the self-regulating environment of the accounting profession to a regulatory framework under the SEC oversight function.

- Causes devastation in the normal operations and performance of alleged companies. Even if a company manages to escape bankruptcy as a result of financial statement fraud, it won't likely do so without experiencing immense financial and reputational damage. Normal operations and performance are bound to suffer as the company faces stock price volatility, difficulties in raising capital, layoffs, fines, legal fees, diminished sales, and other negative consequences.

- Raises serious doubt about the efficacy of financial statement audits. The financial community is demanding high-quality audits, and auditors need to effectively address this issue to produce the desired assurance.

- Erodes public confidence and trust in the accounting and auditing profession. One message that comes through loud and clear these days in response to the increasing number of financial restatements and alleged financial statement fraud is that the public confidence in the financial reporting process and related audit functions is substantially eroded.

FICTITIOUS REVENUES

Fictitious or fabricated revenue schemes involve the recording of sales of goods or services that did not occur. Fictitious sales most often involve fake or phantom customers, but can also involve legitimate customers. For example, a fictitious invoice can be prepared (but not mailed) for a legitimate customer although the goods are not delivered or the services are not rendered. At the beginning of the next accounting period, the sale might be reversed to help conceal the fraud, but this may lead to a revenue shortfall in the new period, creating the need for more fictitious sales. Another method is to use legitimate customers and artificially inflate or alter invoices reflecting higher amounts or quantities than actually sold.

Generally speaking, revenue is recognized when it is (1) realized or realizable and (2) earned. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) Topic 13, “Revenue Recognition” (codified in FASB ASC 605, “Revenue Recognition”), to provide additional guidance on revenue recognition criteria and to rein in some of the inappropriate practices that had been observed. FASB ASC 605 states that revenue is typically considered realized or realizable, and earned, when all of the following criteria are met:

- Persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists

- Delivery has occurred or services have been rendered

- The seller's price to the buyer is fixed or determinable

- Collectibility is reasonably assured

FASB ASC 605 concedes that revenue may be recognized in some circumstances where delivery has not occurred, but sets out strict criteria that limit the ability to record such transactions as revenue.

Properly accounting for revenue is one of the most important and complicated challenges facing companies today. Revenue recognition has always been one of the top accounting and auditing areas of risk. The current conceptual guidelines for revenue recognition are found in FASB Concepts Statement No. 5, “Recognition and Measurement in Financial Statements of Business Enterprises” and FASB Concepts Statement No. 6, “Elements of Financial Statements.” Concepts Statement No. 6 defines revenue as “inflows or other enhancements of assets of an entity or settlements of its liabilities (or a combination of both) from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or other activities that constitute the entity's ongoing major or central operations.” However, because conflicts can arise between the guidance contained in the two applicable Concepts Statements, the FASB is currently working to develop coherent conceptual guidance on revenue recognition to eliminate existing inconsistencies and to provide a basis for a comprehensive accounting standard on revenue recognition.

As part of this initiative, the FASB and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) have partnered on a project to tackle the issue of revenue recognition with the goal of promoting convergence of international accounting standards. The Boards' current perspective on this subject concentrates on “changes in assets and liabilities.” The concept of realization or completion of the earnings processes is not an integral part of their focus in this regard. This is consistent with FASB Concepts Statement No. 6. Although the Boards have arrived at several tentative decisions as part of the project, these decisions do not change current accounting policy until they have gone through extensive due process and deliberations.

Case 1760 details a typical example of fictitious revenue. In this example, a publicly traded company engineered sham transactions for more than seven years in order to inflate their financial standing. The company's management utilized several shell companies, supposedly making a number of favorable sales. The sales transactions were fictitious, as were the supposed customers. As the amounts of the sales grew, so did the suspicions of internal auditors. The sham transactions included the payment of funds for assets while the same funds were returned to the parent company as receipts on sales. The management scheme went undetected for so long that the company's books were eventually inflated by more than $80 million. The perpetrators were finally discovered and prosecuted in both civil and criminal courts.

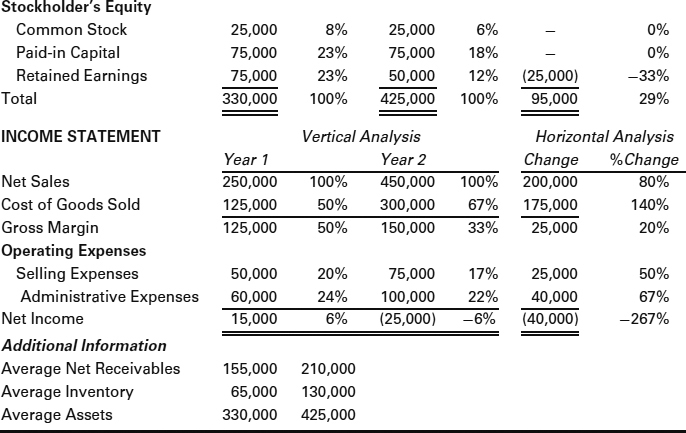

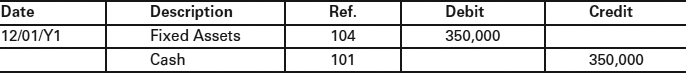

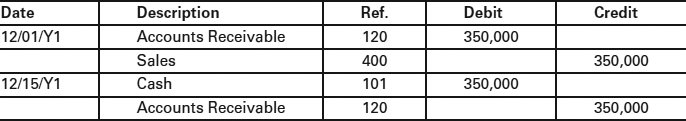

An example of a sample entry from this type of case is detailed below. To record a purported purchase of fixed assets, a fictional entry is made by debiting fixed assets and crediting cash for the amount of the alleged purchase:

A fictitious sales entry is then made for the same amount as the false purchase, debiting accounts receivable and crediting the sales account. The cash outflow that supposedly paid for the fixed assets is “returned” as payment on the receivable account, though in practice the cash might never have moved if the fraudsters hadn't bothered to falsify that extra documentary support.

The result of the completely fabricated sequence of events is an increase in both company assets and yearly revenue. The debit could alternatively be directed to other accounts, such as inventory or accounts payable, or it could simply be left in accounts receivable if the fraud were committed close to year-end and the receivable could be left outstanding without attracting undue attention.

Sales with Conditions

Sales with conditions are a form of a fictitious revenue scheme in which a sale is booked even though some terms have not been completed and the rights and risks of ownership have not passed to the purchaser. These transactions do not qualify for recording as revenue, but they may nevertheless be recorded in an effort to fraudulently boost a company's revenue. These types of sales are similar to schemes involving the recognition of revenue in improper periods since the conditions for sale may become satisfied in the future, at which point revenue recognition would become appropriate. Premature recognition schemes will be discussed later in this chapter in the section on timing differences.

Pressures to Boost Revenues

External pressures to succeed that are placed on business owners and managers by analysts, bankers, stockholders, families, and even communities often provide the motivation to commit fraud. For example, in addition to other charges, General Electric (GE) was alleged by the SEC to have manipulated earnings for two years in a row in order to meet performance targets by recording $381 million in “sales” of locomotives to financial partners. Since GE hadn't ceded ownership of the assets and had agreed to maintain and secure them on its property, the transactions were, in reality, more like loans than sales. GE settled the SEC's charges in 2009 for $50 million, neither admitting nor denying guilt.

In a different case, the former Chairman of Satyam Computer Services, B. Ramalinga Raju, resigned from the board after revealing that he had systematically falsified accounts as the company expanded. He admitted to inflating cash balances and overstating revenues by 20 percent. In 2011 Satyam, now called Mahindra Satyam Ltd, and its auditor, PricewaterhouseCoopers, agreed to pay $125 million and $25.5 million, respectively, to settle claims filed by shareholders. That same year, Satyam and PwC agreed to pay a combined $17.5 million to settle claims made by the SEC and the PCAOB.

In another example, in Case 2303, a real estate investment company arranged for the sale of shares that it held in a nonrelated company. The sale occurred on the last day of the year and accounted for 45 percent of the company's income for that year.

A 30 percent down payment was recorded as received, with a corresponding receivable recorded for the balance. With the intent to show a financially healthier company, the details of the sale were made public in an announcement to the press, but the sale of the stock was completely fabricated. To cover the fraud, off-book loans were made in the amount of the down payment. Other supporting documents were also falsified. The $40 million misstatement was ultimately uncovered, and the real estate company owner faced criminal prosecution.

In a similar instance, Case 710, a publicly traded textile company engaged in a series of false transactions designed to improve its financial image. Receipts from the sale of stock were returned to the company in the form of revenues. The fraudulent management team even went so far as to record a bank loan on the company books as revenue. At the time that the scheme was uncovered, the company books were overstated by some $50,000, a material amount to this particular company.

The pressures to commit financial statement fraud may also come from within a company. Departmental budget requirements including income and profit goals can create situations in which financial statement fraud is committed. In Case 1664, the accounting manager of a small company misstated financial records to cover its financial shortcomings. The financial statements included a series of entries made by the accounting manager designed to meet budget projections and to cover up losses in the company's pension fund. Influenced by dismal financial performance in recent months, the accountant also consistently overstated period revenues. To cover his scheme, he debited liability accounts and credited the equity account. The perpetrator finally resigned, leaving a letter of confession. He was later prosecuted in criminal court.

Red Flags Associated with Fictitious Revenues

- Rapid growth or unusual profitability, especially compared to that of other companies in the same industry

- Recurring negative cash flows from operations or an inability to generate cash flows from operations while reporting earnings and earnings growth

- Significant transactions with related parties or special-purpose entities not in the ordinary course of business or where those entities are not audited or are audited by another firm

- Significant, unusual, or highly complex transactions, especially those close to period end that pose difficult “substance over form” questions

- Unusual growth in the number of days' sales in receivables

- A significant volume of sales to entities whose substance and ownership is not known

- An unusual surge in sales by a minority of units within a company, or of sales recorded by corporate headquarters

TIMING DIFFERENCES

As we mentioned earlier, financial statement fraud may also involve timing differences—that is, the recording of revenue or expenses in improper periods. This can be done to shift revenues or expenses between one period and the next, increasing or decreasing earnings as desired.

Matching Revenues with Expenses

Remember, according to generally accepted accounting principles, revenue and corresponding expenses should be recorded or matched in the same accounting period; failing to do so violates GAAP's matching principle. For example, suppose a company accurately records sales that occurred in the month of December, but fails to fully record expenses incurred as costs associated with those sales until January—in the next accounting period. The effect of this error would be to overstate the net income of the company in the period in which the sales were recorded and also to understate net income in the subsequent period when the expenses are reported.

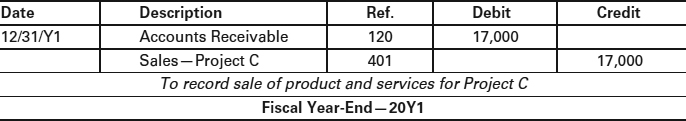

The following example depicts a sales transaction in which the cost of sales associated with the revenue is not recorded in the same period. A journal entry is made to record the billing of a project, which is not complete. Although a contract has been signed for this project, goods and services for this project have not been delivered, and the project is not even scheduled to start until January. In order to boost revenues for the current year, the following sales transaction is recorded fraudulently before year-end:

In January, the project is started and completed. The entries below show accurate recording of the $15,500 of costs associated with the sale:

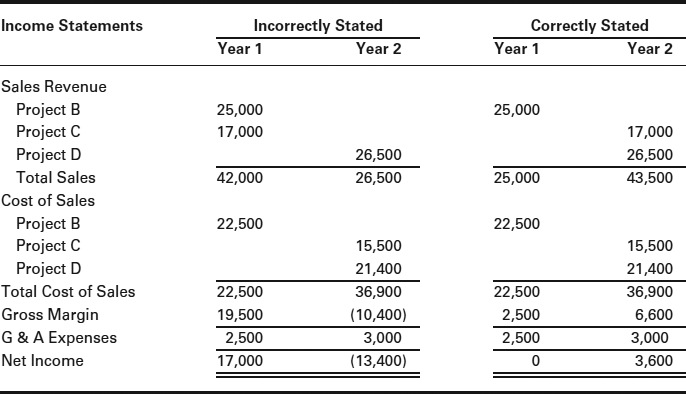

If recorded correctly, the entries for the recognition of revenue and the costs associated with the sales would be recorded in the accounting period in which they actually occurred: January. The effect on the income statement for the company is shown on the next page.

This example depicts exactly how failure to adhere to GAAP's matching principle can cause material misstatement in yearly income statements. When the income and expenses were stated in error, year 1 yielded a net income of $17,000 while year 2 produced a loss ($13,400). Correctly stated, revenues and expenses are matched and recorded together within the same accounting period showing a net income of $0 for year 1 and $3,600 for year 2.

Premature Revenue Recognition

Generally, revenue should be recognized in the accounting records when a sale is complete—that is, when title is passed from the seller to the buyer. This transfer of ownership completes the sale and is usually not final until all obligations surrounding the sale are complete and the four criteria set out in FASB ASC 605 have been satisfied. As mentioned previously, those four criteria are:

- Persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists

- Delivery has occurred or services have been rendered

- The seller's price to the buyer is fixed or determinable

- Collectibility is reasonably assured

Case 861 details how early recognition of revenue not only leads to financial statement misrepresentation, but also can serve as a catalyst to further fraud. A retail drugstore chain's management got ahead of itself in recording income. In a scheme that was used repeatedly, management enhanced its earnings by recording unearned revenue prematurely, resulting in the impression that the drugstores were much more profitable than they actually were. When the situation came to light and was investigated, several embezzlement schemes, false expense report schemes, and instances of credit card fraud were also uncovered.

In Case 2639, the president of a not-for-profit organization was able to illicitly squeeze the maximum amount of private donations by cooking the company books. To enable the organization to receive additional funding, which was dependent on the amounts of already-received contributions, the organization's president recorded promised donations before they were actually received. By the time the organization's internal auditor discovered the scheme, the fraud had been perpetrated for more than four years.

When managers recognize revenues prematurely, one or more of the criteria set forth in FASB ASC 605 is typically not met. Examples of common problems with premature revenue recognition are set out below.

Persuasive Evidence of an Arrangement Does Not Exist

- No written or verbal agreement exists

- A verbal agreement exists, but a written agreement is customary

- A written order exists, but is conditional upon sale to end users (such as a consignment sale)

- A written order exists, but contains a right of return

- A written order exists, but a side letter alters the terms in ways that eliminate the required elements for an agreement

- The transaction is with a related party, but this fact has not been disclosed

Delivery Has Not Occurred or Services Have Not Been Rendered

- Shipment has not been made and the criteria for recognizing revenue on “bill-and-hold” transactions set out in FASB ASC 605 have not been met

- Shipment has been made not to the customer, but to the seller's agent, to an installer, or to a public warehouse

- Some but not all of the components required for operation were shipped

- Items of the wrong specification were shipped

- Delivery is not complete until installation and customer testing and acceptance has occurred

- Services have not been provided at all

- Services are being performed over an extended period, and only a portion of the service revenues should have been recognized in the current period

- The mix of goods and services in a contract has been misstated in order to improperly accelerate revenue recognition

The Seller's Price to the Buyer Is Not Fixed or Determinable

- The price is contingent on some future events

- A service or membership fee is subject to unpredictable cancellation during the contract period

- The transaction includes an option to exchange the product for others

- Payment terms are extended for a substantial period and additional discounts or upgrades may be required to induce continued use and payment instead of switching to alternative products

Collectibility Is Not Reasonably Assured

- Collection is contingent on some future events (e.g., resale of the product, receipt of additional funding, or litigation)

- The customer does not have the ability to pay (e.g., it is financially troubled, it has purchased far more than it can afford, or it is a shell company with minimal assets)

Long-Term Contracts

Long-term contracts pose special problems for revenue recognition. Long-term construction contracts, for example, use either the completed contract method or the percentage of completion method, depending partly on the circumstances. The completed contract method does not record revenue until the project is 100 percent complete. Construction costs are held in an inventory account until completion of the project. The percentage of completion method recognizes revenues and expenses as measurable progress on a project is made, but this method is particularly vulnerable to manipulation. Managers can often easily manipulate the percentage of completion and the estimated costs to complete a construction project in order to recognize revenues prematurely and conceal contract overruns.

Channel Stuffing

Another difficult area of revenue recognition is “channel stuffing,” which is also known as “trade loading.” This refers to the sale of an unusually large quantity of a product to distributors, who are encouraged to overbuy through the use of deep discounts and/or extended payment terms. This practice is especially attractive in industries with high gross margins (cigarettes, pharmaceuticals, perfume, soda concentrate, and branded consumer goods) because it can increase short-term earnings. The downside is that stealing from the next period's sales makes it harder to achieve sales goals in the next period, sometimes leading to increasingly disruptive levels of channel stuffing and ultimately a restatement.

Although orders are received in a channel-stuffing scheme, the terms of the order might raise some question about the collectibility of accounts receivable, and there may be side agreements that grant a right of return, effectively making the sales consignment sales. There may be a greater risk of returns for certain products if they cannot be sold before their shelf life expires. This is particularly a problem for pharmaceuticals, because retailers will not accept drugs that have a short shelf life remaining. As a result, channel stuffing should be viewed skeptically as in certain circumstances it may constitute fraud.

Recording Expenses in the Wrong Period

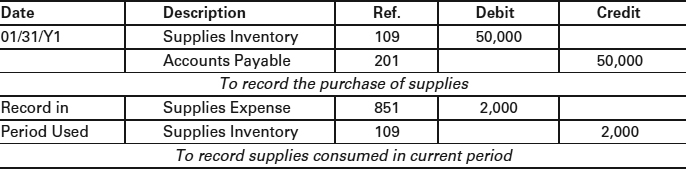

The timely recording of expenses is often compromised due to pressures to meet budget projections and goals, or due to lack of proper accounting controls. As the expensing of certain costs is pushed into periods other than the ones in which they actually occur, they are not properly matched against the income that they help produce. Consider Case 1370, in which supplies were purchased and applied to the current-year budget but were actually used in the following accounting period. A manager at a publicly traded company completed eleven months of operations remarkably under budget when compared to total-year estimates. He therefore decided to get a head start on the next year's expenditures. In order to spend all current-year budgeted funds allocated to his department, the manager bought $50,000 in unneeded supplies. The supplies expense transactions were recorded against the current year's budget. Staff auditors noticed the huge leap in expenditures, however, and inquired about the situation. The manager came clean, explaining that he was under pressure to meet budget goals for the following year. Because the manager was not attempting to keep the funds for himself, no legal action was taken.

The correct recording of the above transactions would be to debit supplies inventory for the original purchase and subsequently expense the items out of the account as they are used. The example journal entries below detail the correct method of expensing the supplies over time.

Similar entries should be made monthly, as the supplies are used, until they are consumed and $50,000 in supplies expense is recorded.

Red Flags Associated with Timing Differences

- Rapid growth or unusual profitability, especially compared to that of other companies in the same industry

- Recurring negative cash flows from operations or an inability to generate cash flows from operations while reporting earnings and earnings growth

- Significant, unusual, or highly complex transactions, especially those close to period-end that pose difficult “substance over form” questions

- Unusual increase in gross margin or margin in excess of industry peers

- Unusual growth in the number of days' sales in receivables

- Unusual decline in the number of days' purchases in accounts payable

CASE STUDY: THE IMPORTANCE OF TIMING2

What about a scheme in which nobody gets any money? One that was never intended to enrich its players or to defraud the company they worked for? It happened in Huntsville, Alabama, on-site at a major aluminum products plant with over $300 million in yearly sales. A few shrewd men cooked the company's books without taking a single dime for themselves. Terry Isbell was an internal auditor making a routine review of accounts payable. He was running a computer search to look at any transactions over $50,000 and found among the hits a bill for replacing two furnace liners. The payments went out toward the last of the year, to an approved vendor, with the proper signatures from Steven Leonyrd, a maintenance engineer, and Doggett Stine, the sector's purchasing manager. However, there was nothing else in the file. Maintenance and repair jobs of this sort were supposed to be done on a time-and-material basis. So there should have been work reports, vouchers, and inspection sheets in the file along with the paid invoices. But there was nothing.

Isbell talked with Steven Leonyrd, who showed him the furnaces, recently lined and working to perfection. So where was the paperwork? “It'll be in the regular work file for the first quarter,” Leonyrd replied.

“The bill was for last year, November and December,” Isbell pointed out. That was because the work was paid for in “advance payments,” according to Leonyrd. There wasn't room in the work schedule to have the machines serviced in November, so the work was billed to that year's nonrecurring maintenance budget. Later, sometime after the first of the year, the work was actually done.

Division management okayed Isbell to make an examination. He found $150,000 in repair invoices without proper documentation. The records for materials and supplies, which were paid for in one year and received in the next, totaled $250,000. A check of later records and an inspection showed that everything paid for had in fact been received—just later than promised. So it was back to visit Leonyrd, who said the whole thing was simple. “We had this money in the budget for maintenance and repair, supplies outside the usual scope of things. It was getting late in the year, looked like we were just going to lose those dollars, you know, they'd just revert back to the general fund. So we set up the work orders and made them on last year's budget. Then we got the actual stuff later.” Who told Leonyrd to set it up that way? “Nobody. Just made sense, that's all.”

Nobody, Isbell suspected, was the purchasing manager who handled Leonyrd's group, Doggett Stine. Stine was known as “a domineering-type guy” among the people who worked for him, a kind of storeroom bully. Isbell asked him about the arrangement with Leonyrd. “That's no big deal,” Stine insisted. “Just spent the money while it was there. That's what it was put there for, to keep up the plant. That's what we did.” It wasn't his idea, said Stine, but it wasn't really Leonyrd's either, just a discussion and an informal decision. The storeroom receiving supervisor agreed it was a grand idea and made out the documents as he was told. Accounting personnel processed the invoices as they were told. A part-time bookkeeper said to Isbell she remembered some discussion about arranging to spend the money, but she didn't ask any questions.

Isbell was in a funny position, a little bit like Shakespeare's Malvolio, who spends his time in the play Twelfth Night scolding the other characters for having such a good time. Leonyrd hadn't pocketed anything, and neither had Stine; being a bully was hardly a fraudulent offense. There was about $6,000 in interest lost, supposing the money had stayed in company bank accounts, but that wasn't exactly the point. More seriously, this effortless cash-flow diversion represented a kink in the handling and dispersal of funds. Isbell wasn't thinking rules for their own sake or standing on ceremony—money this easy to come by just meant the company had gotten a break. The next guys might not be so civic-minded and selfless; they might start juggling zeros and signatures instead of dates.

Under Isbell's recommendation, the receiving department started reporting directly to the plant's general accounting division, and its supervisor was assigned elsewhere. Doggett Stine had subsequently retired. Steven Leonyrd was demoted and transferred to another sector; he was fired a year later for an unrelated scheme. He had approached a contractor to replace the roof on his house, with the bill to be charged against “nonrecurring maintenance” at the plant. But the contractor alerted plant officials to their conniving employee, who was also known to be picking up extra money for “consulting work” with plant-related businesses. Rats, Leonyrd must have thought, foiled again.

CONCEALED LIABILITIES AND EXPENSES

As previously discussed, understating liabilities and expenses is one of the ways that financial statements can be manipulated to make a company appear more profitable. Because pretax income will increase by the full amount of the expense or liability not recorded, this financial statement fraud method can have a significant impact on reported earnings with relatively little effort by the fraudster. This method is much easier to commit than falsifying many sales transactions. Missing transactions are generally harder for auditors to detect than improperly recorded ones, because there is no audit trail.

There are three common methods for concealing liabilities and expenses:

- Liability/expense omissions

- Capitalized expenses

- Failure to disclose warranty costs and liabilities

Liability/Expense Omissions

The preferred and easiest method of concealing liabilities/expenses is to simply fail to record them. Multimillion-dollar judgments against the company from a recent court decision might be conveniently ignored. Vendor invoices might be thrown away (they'll send another later) or stuffed into drawers rather than being posted into the accounts payable system, thereby increasing reported earnings by the full amount of the invoices. In a retail environment, debit memos might be created for chargebacks to vendors, supposedly to claim permitted rebates or allowances but sometimes just to create additional income. These items may or may not be properly recorded in a subsequent accounting period, but that does not change the fraudulent nature of the current financial statements. One of the highest-profile liability omission cases of recent vintage involved Adelphia Communications. John Rigas, Adelphia's founder, purchased a small cable company in Coudersport, Pennsylvania for the sum of $300 in 1952. By 2002, it had grown to the nation's sixth-largest cable television company, with more than five million subscribers and $10 billion in assets.

Rigas, of Greek heritage, named his company Adelphia Communications Corporation, after the Greek word for “brothers.” He and his brother Gus ran the company as their own—a style that came back to haunt him after the company went public. Later, his three sons Tim, Michael, and James—along with son-in-law Peter Venetis—became active in Adelphia's management. The family controlled the majority of the company's voting stock and constituted the majority on the board of directors. Accordingly, the family used Adelphia's money as their own. They also used company assets as their own. Three corporate jets took family members on exotic vacations, including African safaris. John Rigas was particularly egregious in his spending. At one time, he racked up personal debt of $66 million, forcing his son, Timothy, to put his father on a “budget” of $1 million a month in personal draws.

Adelphia CFO Timothy Rigas engineered the financial manipulations. He was in charge of manipulating the books to inflate the stock price in order to meet analysts' expectations. Investigators later discovered that the family members had looted the company to the tune of some $3 billion. The money transfers were made by journal entries that gave Adelphia debt that hadn't been disclosed. Among other things, the Rigas family used the funds to:

- Acquire other cable companies not owned by Adelphia

- Pay debt service on investments

- Purchase a controlling interest in the Buffalo Sabres Hockey Team

- Pay $700,000 in country club memberships

- Buy luxury vacation homes in Cancun, Beaver Creek (Colorado), and Hilton Head Island, as well as two apartments in Manhattan

- Purchase a $13 million golf course

The Rigas family's problems started with overexpansion in the late 1990s when they purchased Century Communications for the sum of $5.2 billion. By 2002, Adelphia's stock had fallen to historic lows and the company was unable to make payments on the debt it incurred to make acquisitions.

In July 2002, the SEC charged Adelphia with, among other things, fraudulently excluding over $2.3 billion in bank debt from its consolidated financial statements. According to the complaint filed by the SEC, Adelphia's founder and his three sons fraudulently excluded the liabilities from the company's annual and quarterly consolidated financial statements by deliberately shifting those liabilities onto the books of Adelphia's off–balance sheet unconsolidated affiliates. Failure to record this debt violated GAAP requirements and precipitated a series of misrepresentations about those liabilities by Adelphia and the defendants. This included the creation of (1) sham transactions backed by fictitious documents to give the false appearance that Adelphia had actually repaid debts when, in truth, it had simply shifted them to unconsolidated entities controlled by the founder and (2) misleading financial statements that, in their footnotes, gave the false impression that liabilities listed in the company's financials included all outstanding bank debt. This led to a freefall of Adelphia's stock; less than three months later, the company filed for bankruptcy.

Often, perpetrators of liability and expense omissions believe they can conceal their fraud in future periods. They often plan to compensate for their omitted liabilities with visions of other income sources such as profits from future price increases.

Just as they are easy to conceal, omitted liabilities are probably one of the most difficult financial statement schemes to uncover. A thorough review of all post-financial statement-date transactions, such as accounts payable increases and decreases, can aid in the discovery of omitted liabilities in financial statements, as can a computerized analysis of expense records. Additionally, if the auditor requested and was granted unrestricted access to the client's files, a physical search could turn up concealed invoices and unposted liabilities. Probing interviews of accounts payable and other personnel can reveal unrecorded or delayed items, too.

Capitalized Expenses

Capital expenditures are costs that provide a benefit to a company over more than one accounting period. Manufacturing equipment is an example of this type of expenditure. Revenue expenditures or expenses, on the other hand, directly correspond to the generation of current revenue and provide benefits for only the current accounting period. An example of expenses is labor costs for one week of service. These costs correspond directly with revenues billed in the current accounting period.

Capitalizing revenue-based expenses is another way to increase income and assets, since they are amortized over a period of years rather than expensed immediately. If expenditures are capitalized as assets and not expensed during the current period, income will be overstated. As the assets are depreciated, income in subsequent periods will be understated.

The improper capitalization of expenses was one of the key methods of financial statement fraud that was allegedly used by WorldCom, Inc., in its high-profile fraud, which came to light in early 2002. The saga of WorldCom, at one time the second-largest long-distance carrier in America (behind AT&T), began in 1983, when Bernie Ebbers drew a business plan on the back of a napkin at a coffee shop in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Ebbers and his partners, attempting to benefit from the breakup of AT&T, decided to purchase long-distance time and sell it to local companies on a smaller scale. They named the fledgling business Long Distance Discount Service (LDDS).

Up until that time, Ebbers didn't know much about the telecommunications industry. He graduated from a small Mississippi college with a degree in physical education. He'd previously owned a small garment factory and several motels.

But LDDS turned out to be a success. The company was buying and selling a commodity—long-distance service—but it didn't have to invest in the costs of buying and installing expensive telephone lines. Along the way, LDDS acquired a half-dozen other communications companies.

In 1995, the business was renamed WorldCom, and the new company went on an acquisition rampage, purchasing over sixty companies. WorldCom's crown jewel was a $37 billion merger in 1997 with MCI, a much larger company. The following year, it bought Brooks Fiber Properties and CompuServe. In 1999, it attempted to acquire rival Sprint in a $115 billion merger, but the Federal Communications Commission blocked the deal to prevent breach of antitrust laws.

Because of increasing competition in the telecommunications industry, WorldCom's spectacular growth started slowing dramatically resulting in a precipitous drop in its stock price. To reverse declining margins, the company started reducing the reserves it had established to cover the undisclosed liabilities of companies it had acquired. Between 1998 and 2000, this amounted to $2.8 billion.

However, in the opinion of management, the reduction in reserves was insufficient. Scott Sullivan, the CFO, directed certain WorldCom staffers to reclassify as assets $3.35 billion in fees paid to lease phone networks from other companies and $500 million in computer expenses, both operating costs. Rather than suffering a $2.5 billion loss in 2001, the company reported a $1.4 billion profit. Andersen LLP, WorldCom's external auditors, uncovered none of these machinations.

In 2002, Sullivan directed a WorldCom employee to classify another $400 million in expenses as assets. The employee complained to Cynthia Cooper, CFE, WorldCom's internal auditor, who directed her staff to conduct an investigation. Cooper's team first discovered that the $500 million in computer expenses reclassified as assets had no documentation to support the expenditures. Then they uncovered another $2 billion in questionable entries.

Internal auditors met with the audit committee in June 2002 to explain their findings. On June 25, WorldCom made a public announcement that it had inflated revenues by $3.8 billion over the previous five quarters. Within three weeks, the company had filed for bankruptcy. Subsequent investigations would show that WorldCom had overstated its profits and income by about $11 billion.

These improper accounting practices were designed to, and did, inflate income to correspond with estimates by Wall Street analysts and to support the price of WorldCom's stock. As a result, several former WorldCom Executives, including former CEO Bernie Ebbers, former CFO Scott Sullivan, former Controller David F. Meyers, and former Director of General Accounting Buford “Buddy” Yates, Jr., were charged with multiple criminal offenses and received prison sentences ranging from one to twenty-five years for their participation in the scheme.

Expensing Capital Expenditures

Just as capitalizing expenses is improper, so is expensing costs that should be capitalized. An organization may want to minimize its net income due to tax considerations or to increase earnings in future periods. Expensing an item that should be depreciated over a period of time helps accomplish just that—net income is lower and so are taxes.

Returns and Allowances and Warranties

Improper recording of sales returns and allowances occurs when a company fails to properly record or present the expense associated with sales returns and customer allowances stemming from customer dissatisfaction. It is inevitable that a certain percentage of products sold will, for one reason or another, be returned. When this happens, management must record the related expense in a contra-sales account, which reduces the amount of net sales presented on the company's income statement.

Likewise, when a company offers a warranty on product sales, it must estimate the amount of warranty expense it reasonably expects to incur over the warranty period and accrue a liability for that amount. In warranty liability fraud, the warranty liability is usually either omitted or substantially understated. Another similar area is the liability resulting from defective products (product liability).

Red Flags Associated with Concealed Liabilities and Expenses

- Recurring negative cash flows from operations or an inability to generate cash flows from operations while reporting earnings and earnings growth

- Assets, liabilities, revenues, or expenses based on significant estimates that involve subjective judgments or uncertainties that are difficult to corroborate

- Nonfinancial management's excessive participation in or preoccupation with the selection of accounting principles or the determination of significant estimates

- Unusual increase in gross margin or margin in excess of industry peers

- Allowances for sales returns, warranty claims, and so on that are shrinking in percentage terms or are otherwise out of line with industry peers

- Unusual reduction in the number of days' purchases in accounts payable

- Reducing accounts payable while competitors are stretching out payments to vendors

IMPROPER DISCLOSURES

As we discussed earlier, accounting principles require that financial statements and notes include all the information necessary to prevent a reasonably discerning user of the financial statements from being misled. The notes should include narrative disclosures, supporting schedules, and any other information required to avoid misleading potential investors, creditors, or any other users of the financial statements.

Management has an obligation to disclose all significant information appropriately in the financial statements and in management's discussion and analysis. In addition, the disclosed information must not be misleading. Improper disclosures relating to financial statement fraud usually involve the following:

- Liability omissions

- Subsequent events

- Management fraud

- Related-party transactions

- Accounting changes

Liability Omissions

Typical omissions include the failure to disclose loan covenants or contingent liabilities. Loan covenants are agreements, in addition to or part of a financing arrangement, which a borrower has promised to keep as long as the financing is in place. The agreements can contain various types of covenants, including certain financial ratio limits and restrictions on other major financing arrangements. Contingent liabilities are potential obligations that will materialize only if certain events occur in the future. A corporate guarantee of personal loans taken out by an officer or a private company controlled by an officer is an example of a contingent liability. The company's potential liability, if material, must be disclosed.

Subsequent Events

Events occurring or becoming known after the close of the period may have a significant effect on the financial statements and should be disclosed. Fraudsters often avoid disclosing court judgments and regulatory decisions that undermine the reported values of assets, that indicate unrecorded liabilities, or that adversely reflect on management integrity. Public record searches can reveal this information.

Management Fraud

Management has an obligation to disclose to the shareholders significant fraud committed by officers, executives, and others in positions of trust. Withholding such information from auditors would likely also involve lying to auditors, an illegal act in itself.

Related-Party Transactions

Related-party transactions occur when a company does business with another entity whose management or operating policies can be controlled or significantly influenced by the company or by some other party in common. There is nothing inherently wrong with related-party transactions, as long as they are fully disclosed. If the transactions are not conducted on an arm's-length basis, the company may suffer economic harm, injuring stockholders.

The financial interest that a company official might have may not be readily apparent. For example, common directors of two companies that do business with each other, any corporate general partner and the partnerships with which it does business, and any controlling shareholder of the corporation with which he/she/it does business may be related parties. Family relationships can also be considered related parties. These relationships include all lineal descendants and ancestors, without regard to financial interests. Related-party transactions are sometimes referred to as “self-dealing.” While these transactions are sometimes conducted at arm's length, they often are not.

In the highly publicized Tyco fraud case, which broke in 2002, the SEC charged former top executives of the company, including its former CEO, L. Dennis Kozlowski, with failing to disclose to shareholders hundreds of millions of dollars of low-interest and interest-free loans they took from the company. Moreover, Kozlowski forgave $50 million in loans to himself and another $56 million for fifty-one favored Tyco employees. Tyco's board approved none of the charges.

Kozlowski also engaged in undisclosed non-arm's-length real estate transactions with Tyco or its subsidiaries and received undisclosed compensation and perks, including rent-free use of large New York City apartments and personal use of corporate aircraft at little or no cost. The SEC complaint alleged that three former executives, including Kozlowski, also sold restricted shares of Tyco stock valued at $430 million dollars while their self-dealing remained undisclosed.

In addition, Kozlowski participated in numerous improper transactions to fund an extravagant lifestyle. In January 2002, several empty boxes arrived at Tyco's headquarters in Exeter, New Hampshire. They were supposed to contain art worth at least $13 million to decorate the modest, two-story facility. In fact, the art—consisting of original works by Renoir and Monet—was actually hanging on the walls in Kozlowski's lavish Fifth Avenue corporate apartment; the empty-box ruse had been staged in an effort to avoid New York State sales tax of 8.25 percent.

Less than six months later, Kozlowski resigned just before he was accused of evading payment of taxes on the art. But the art, paid for by Tyco, was just the tip of the iceberg. A subsequent investigation would accuse Kozlowski and CFO Mark Schwartz of systematically looting their employer for more than $170 million. Both men were later found guilty of twenty-two charges and sentenced to up to twenty-five years in prison.

Most of the stolen money was simply charged to Tyco even though it personally benefited Kozlowski. For example, his compensation was reported at $400 million, but, in addition, Tyco paid for such outrageous charges as:

- A $16.8 million apartment in New York City for Kozlowski

- $13 million in original art

- A $7 million apartment for Kozlowski's ex-wife

- An umbrella stand that cost $15,000

- A $17,000 traveling toilette box

- $5,960 for two sets of sheets

- A $6,300 sewing basket

- A $6,000 shower curtain

- Half of a $2.1 million birthday party for his wife

- Up to $80,000 a month in personal credit card charges

Although Kozlowski's embezzlements were not material to the financial statements as a whole, they were nonetheless substantial and vividly portray the ultimate in corporate greed.

Accounting Changes

FASB ASC 250, “Accounting Changes and Error Corrections,” describes three types of accounting changes that must be disclosed to avoid misleading the user of financial statements: accounting principles, estimates, and reporting entities. Although the required treatment for each type of change is different, they are all susceptible to manipulation by determined fraudster. For example, fraudsters may fail to properly retroactively restate the financial statements for a change in accounting principle if the change causes the company's financial statements to appear weaker. Likewise, they may fail to disclose significant changes in estimates such as the useful lives and estimated salvage values of depreciable assets or the estimates underlying the determination of warranty or other liabilities. They may even secretly change the reporting entity, by adding entities owned privately by management or excluding certain company-owned units, in order to improve reported results.

Red Flags Associated with Improper Disclosures

- Domination of management by a single person or small group (in a non-owner-managed business) without compensating controls

- Ineffective board of directors or audit committee oversight over the financial reporting process and internal control

- Ineffective communication, implementation, support, or enforcement of the entity's values or ethical standards by management or the communication of inappropriate values or ethical standards

- Rapid growth or unusual profitability, especially compared to that of other companies in the same industry

- Significant, unusual, or highly complex transactions, especially those close to period-end that pose difficult “substance over form” questions

- Significant related-party transactions not in the ordinary course of business or with related entities not audited or audited by another firm

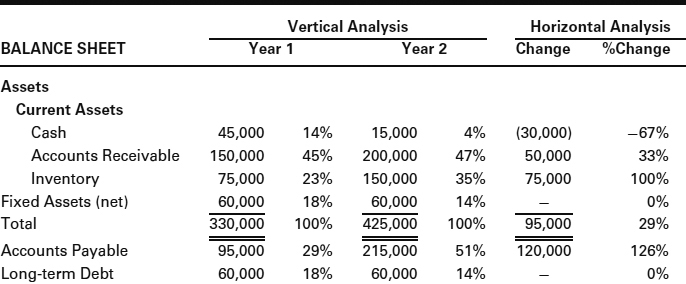

- Significant bank accounts or subsidiary or branch operations in tax-haven jurisdictions for which there appears to be no clear business justification