Chapter 4

Wiring the School for Socioemotional Learning

One common theme of the post-pandemic world is the increased interest in socioemotional learning (SEL) among schools and educators. Not that SEL wasn't plenty familiar to most educators already, but two years marked by increased stress, isolation, and loneliness for thousands of kids “turbocharged” interest in it, as education policy expert Rick Hess recently put it.

Not only have many young people been through challenging and difficult experiences, but in many cases long periods of isolation have resulted in diminished social skills that have left them less able to manage everyday conflicts and challenges now that they're back in schools. Doug recently met with school leaders in Texas and asked them about the emotional and psychological status of their students. Had they come back to school behaving differently? Of the more than 180 people in the room perhaps 3 or 4 did not agree that students had changed. One leader described how students were impatient with each other and how misunderstandings or small slights escalated quickly. “Even with their friends, the slightest things cause a flareup.”

“They struggle to show each other the basic empathy they all need,”1 another said. There were academic effects too. “They give up much more quickly in the face of difficulty than kids did before the pandemic,” an administrator opined and the room nodded as one. And in particular, they reported that classroom behavior was dramatically worse—the rate of disruptions was higher, the basic willingness to do as asked was lower, and highly emotional responses to the setting of limits were more frequent.

So it's an especially critical time for schools to ensure that students thrive not just academically, but also psychologically and emotionally. That idea is a “variation on a historical theme,” Hess and Tim Shriver, board chair of the Collaborative for Academic Social and Emotional Learning, recently wrote. “Since the dawn of the republic, teachers and schools have been tasked with teaching content and modeling character.”

A few weeks after Doug's meeting in Texas, we convened a group of school leaders to ask their opinion their students' emotional well-being. “On a socioemotional level, we have seen less development and maturity from students than we have in previous years at a particular grade level,” Rhiannon Lewis, a school leader at Memphis Rise in Memphis, Tennessee, told us. “The ability to self-regulate is a bit less developed, and we can only guess that this is due to the lack of socioemotional support during the pandemic that has left this long-term impact.” David Adams, CEO of the Urban Assembly's 23 district schools in New York City, noted:

“I've seen students become more sensitive in interactions. The notion of how to interact, that there are social norms that are guiding you—my students are really having difficulty navigating conflict. Escalation comes a lot faster than it used to. Persistence is another challenge—persisting in work, persisting in relationships. Some of the things that were more taken for granted need to be really more explicitly taught.”

Adams's comments reveal one of many carry-on effects for students when they struggle to connect with each other and resolve minor difficulties. It means disrupted relationships between and among young people. Losing a friend over some initially small incident seems especially sad in a time when young people so badly need every valuable connection.

So an increased emphasis on SEL is a worthwhile response to the present context, and in this chapter we'll try to sketch out specific approaches and general rules of thumb for rebuilding social and emotional capacity in students. But we also offer some caveats, because helping students navigate challenging situations is challenging in and of itself. SEL interventions can be faddish. They can be rushed into service with little evidence to support them. And there's the risk that we'll be lured into believing that a single action or program can solve the issue we face. Most likely to help, we think, is the careful selection of manageable strategic efforts that focus on rewiring daily social interactions and cognitive habits to build socioemotional capacity in students. In Chapter 3 on rewiring the classroom, we talked about the need to maximize frequent, often small signals of belonging. In writing about building socioemotional health, we argue for wiring the building to send constant, often small signals to reinforce mindsets and behaviors that foster well-being.

One benefit of that approach is that it can help us avoid what UK education writer Joe Kirby calls hornets: “high-effort, low-impact ideas” of the sort that schools may do out of best intentions. Good schools, Kirby notes, have to avoid doing every good thing so they can focus on the most important things and “put first things first.” A hornet isn't a counterproductive or ineffective idea. It's a moderately helpful thing that keeps us from focusing on activities that help students more. Resources are finite, even when our hope and caring for young people is unlimited. Using up time and effort on moderately useful activities tires out staff and degrades their ability to teach well and be emotionally present for students.

More SEL is not necessarily better, in other words. Consistency, quality of offerings, and return on effort should be the goals. We have a lot to accomplish in schools right now—it's a once-in-a-generation learning crisis as well—and most importantly, only well-run activities build students' sense of belonging and well-being. A class to build SEL skills two or three mornings a week with every teacher in the school leading a section might be a difference maker, but only if all of those teachers were well prepared with excellent lesson plans that are interesting and helpful to students. If the teachers aren't prepared and don't teach well, if the room in which we're talking SEL doesn't walk the SEL walk and make students feel signals of belonging and inclusion like we saw in Chapter 3, it won't help much. Indifferently run activities don't move the needle much. And well-run activities—as Chapter 3 also showed—require planning, preparation, and training.

Rather than pressing every lever, we should choose the most effective ones. This applies to everything we do in schools, but it's especially relevant in a discussion of SEL because another challenge is that it can be vaguely defined and because positive outcomes can be presumed to result from good intentions alone.

Consider a recent report by the highly regarded Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) called “10 Years of Social and Emotional Learning in US School Districts.”2 It defined SEL as “the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills and attitude to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships and make responsible and caring decisions.” That’s a sprawling definition to put it mildly, and a goal with a definition that excludes nothing is problematic operationally. What activity can a staff member propose under the aegis of improving SEL and have school leaders realize that it's of secondary importance or not germane at all?

The report's approach to data doesn't help much either. Its retrospective analysis of ten years of investment in SEL across multiple large districts offers little insight on which methods or ideas worked best and delivered maximum return for effort. They highlight a small number (three) of less-than-overwhelming data points, including a district that “reported an overall improvement in school climate, as measured by student responses on the annual climate and connectedness survey … [of] four percentage points (from 68% to 72%) and student perceptions of caring others increased by two percentage points (from 63% to 65%).” There's no analysis of the correlation to specific actions, never mind causation.

A tiny improvement in a subjective survey instrument in a district where dozens of factors (including randomness) could have driven a marginal perception of change does not exactly build an unimpeachable case for the report's conclusion: sustained districtwide focus and expanded funding are required. Such a strategy doesn't make it more likely SEL programs will work. It merely opens the idea to concept drift—if everything is SEL, nothing is. And it makes it more likely that wide-ranging nonstrategic efforts will be ineffective or consume scarce resources.

A final caveat: it's important to remember that teachers are not trained mental health professionals. We should be cautious about presuming their capacity to delve into areas where social workers and counselors are better suited and more qualified.

START WITH VIRTUES

Fortunately, we think there is a path forward—one that starts with but need not consist exclusively of character education, an element of SEL that involves the intentional naming and reinforcing of virtues that make the community and its members more likely to thrive and succeed. What are virtues? you might ask. University of Pennsylvania psychologist Angela Duckworth describes them as “ways of thinking, feeling and acting that we [can] habitually do that are good for others and good for ourselves.” Implicit in that definition of virtue is both an individual and a group dynamic—one reason why we think character education is so important. Virtues are “positive personal strengths”3 that help individuals succeed, that help them feel happier and more fulfilled, and that also build community. A school full of character and virtue is likely to be a place where people feel valued, important, and connected.

To clarify, there are a variety of approaches schools can take to socioemotional learning; we will describe several in this chapter and our assumption is that different schools will have different needs. But we argue that one foundational piece of the solution for many schools is an emphasis on building virtues though character education. For some schools, rebuilding atrophied social skills or investing in mindfulness will also (or alternatively) be important. In other cases, providing interventions for a narrower group of students who struggle most will be critical. Of course, there are other beneficial programs schools can consider. Many of them are excellent and we don't propose what we describe here to be comprehensive. Rather, we offer an approach we think can deliver immense benefits in well-being and belonging to a large number of students at a manageable cost of time and effort and can be implemented by most educators without significant additional training. It's a sensible approach that can add broad value at a time when schools are pulled in a dozen directions.

KNOWLEDGE, PERCEPTION, AND REASONING

Character education focuses on instilling virtues that allow individuals and communities to thrive. To do that, the Jubilee Centre on Character Education's “Character Education Framework” advises, schools should emphasize virtue knowledge (helping students to understand what virtues are and why they are beneficial), virtue perception (helping students to notice virtues more readily as they occur in the world around them and how they shape the community), and virtue reasoning (supporting students in making decisions about when and how they apply those virtues in their own lives).4

That's a compelling recipe for long-term learning, but character education has its skeptics too. To some people the idea smacks of paternalism—how can one person say what characteristics are virtuous? To others it smacks of politicization—character virtues will be a vehicle for proselytizing values in an agenda that is not their own.

We argue that we are always teaching values, whether we realize it or not. By seeking to focus transparently on a set that is as close to universal and as optimally beneficial as we can get, we can mitigate these concerns. We should seek out traits that the greatest number of parents (and hopefully students) place value on and that we have reason to believe will really help students, doubly so if we maintain a focus on virtues that build both connection among community members and also foster learning—the ultimate purpose of school.

One of the themes of this book is being attentive to process in order to gain more buy-in from stakeholders. Character education is a perfect example of a time to be intentional about process. By being transparent about what virtues it has chosen and why, and by asking parents for input on the virtues it chooses, a school can reassure parents who may be skeptical and ensure their trust in how the school seeks to support their children. To state the obvious, this is important because our work as educators is to help parents to raise their children. We, your authors, frequently use the expression “our kiddos” or “our students” but that is merely an expression, a signal of our commitment to and caring for the children and families we serve. Effective character education (and SEL more broadly) requires input from and connection with all stakeholders–students, faculty, and families—but especially parents. It should reflect their values. Our private values may not jibe perfectly with every member of the school community but we can and should seek consensus values, the best possible representation of the things we all agree on most, and that is a process that will require input and listening.

So the process should start by explicitly naming virtues the school aspires to uphold and reinforce. As Angela Duckworth also points out, character education and socioemotional work more broadly are not guesswork. There is science—a great deal of it—to help guide us toward the most important virtues and traits that most build well-being and connectedness.

As a starting point in thinking about character virtues, we love this chart5 developed by the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues in the UK. They differentiate four types of virtues: intellectual virtues (such as critical thinking and curiosity), moral virtues (such as compassion and respect), civic virtues (such as service and civility), and performance virtues (such as teamwork and perseverance). Even before we get down to a discussion of which virtues matter most, the idea of seeing them in categories, each with a broader purpose, is helpful. It helps to answer the question of why. Our goal is for young people to be equipped to “pursue knowledge, truth, and understanding,” to be prepared to “act well in situations that require an ethical response,” to be able and willing to contribute to “the common good” in a variety of situations, and to have a set of “enabling” skills like determination and resilience that can help them accomplish the first three—and most other goals in their lives. To us as parents, family members, and educators, the power of the chart is as much in those categories as the individual virtues. Reading it helped us to see the broader purpose in character work and how different parts fit together. We suspect that a parent—even a skeptical one—glimpsing such a framework would feel reassured and informed.

So start by choosing and naming virtues, but remember that understanding “why”—the purposes of the virtues in a well-lived and healthy life—is critical. We don't personally recommend choosing all or even most of the virtues proposed in the Jubilee Centre's framework. There are far too many to focus on and reinforce well. A few key ideas deeply understood and valued are better than a list of terms. And frankly, some are inevitably more important than others. Choose a handful—we'd suggest five to seven—that align with your mission and are most compelling to the parents in your school's community, and then build them into the fabric of the school. For what it's worth, we think the authors of the framework would agree. In describing “examples” of virtues that would fall into each of the four categories, they show that their assumption is that people will chose, select, and prioritize these or others. We like that too because the words matter. Do we, your authors, perceive a difference between diligence and perseverance, for example? Yes, we do.6 Which word you pick—and how you define it—matters.

BUILD THEM INTO THE FABRIC OF YOUR SCHOOL

Once you've chosen virtues, the next step is to build them into the fabric of the school. The key to instilling beneficial habits of mind for young people is to reinforce them throughout the school day. Strong character and healthy mindsets are far less likely to thrive if they only come up during a specific block of time! Character can and should be reinforced while community members are doing other things; perhaps it's best reinforced that way. After all, if you truly value compassion, you should value it and look for it everywhere. It's better to show appreciation for it throughout the school day than to design an hour, twice a week, when we attend to things like compassion. It can start there perhaps, but the important part is the message that we should always be thinking about the people we want to be.

Another way of putting this is that to be successfully instilled in the life of a school, virtues should be taught, caught, and sought;7 that is, students should understand what they are and how they are beneficial, then the school should set out to increase their visibility so that they are clearly valued and are more readily apparent as community norms. Over time, the culture should attempt to socialize students to internalize the virtues—to seek them because they perceive them to be part of who they are or want to be. They should also be modeled intentionally and consistently by the adults.8

Making sure virtues are taught means providing not just definitions but also examples and applications. This might start at a schoolwide community meeting or perhaps a grade-level meeting where the reasons why the virtues matter are shared, perhaps with a few personal stories from the adults. We're big believers in active practice when learning vocabulary in academic classes. Active practice means giving students the definition of a term (rather than asking them to try to guess at it) and then allowing them to apply it in challenging situations. Jen Brimming did that with the word “reprehensible” in the video from Chapter 3. Students are engaged because they are asked to apply a term they know in complex and challenging cases: Why is it bad to steal but reprehensible to steal from a charity? Why is being a hypocrite reprehensible? Which characters from various books we've read are reprehensible and why?

Building knowledge of virtues could look similar. At a grade-level or schoolwide meeting, you could explain briefly that gratitude means showing appreciation and thanks for the things people do for you, and then ask students (perhaps via a series of Turn and Talks) to reflect on a series of questions about it:

- What's a situation in which a student might show gratitude to a teacher?

- What's a situation where a teacher might show gratitude to a student?

- Saying “thank you” is a common way to show gratitude but there are other ways. What's a way you might show gratitude that does not involve saying anything?

- How might you show gratitude to someone who found your dog after it ran away? How might you show your gratitude to them if it turned out they didn't speak any of the same languages as you?

- What's something people forget to show gratitude for?

- What's something a pet might show gratitude for, and how might he or she show it?

- Do we always have to express gratitude to a single person? Try to think of an example of how and why you'd express gratitude to something other than one individual.

Questions like these require thinking and reasoning on one hand and discretion and adaptation on the other. They grow students' understanding of a concept but also ask them to think about how they would apply it in their own lives. How each student answers the last question is a personal reflection. Later you might ask students to think even more deeply about it:

- What's a time when you didn't show gratitude when you wish you had?

- Describe a time when someone showed gratitude to you that you still remember.

We say “later” in describing when you might ask this second group of questions because there are very few concepts we can master in one interaction. Learning requires constant discussion, reflection, and expansion over time. We need to keep talking about virtues to make them meaningful. Better to spend ten minutes discussing gratitude five times over the course of a month than to spend one hour discussing it once and then letting it drop.

We were struck recently by a video we observed of Equel Easterling teaching virtues in his classroom at North Star Clinton Hill Middle School in Newark, New Jersey. His session was focused on introducing the concept of gratitude. (As we'll discuss later, research somewhat suggests that gratitude is perhaps the single most powerful virtue for student well-being.)

Equel starts by asking students what gratitude is. They provide examples and descriptions. Then he defines the term formally and asks them to reason about it based on a video: How were the people in the video showing gratitude and why was it valuable? Notice the degree of peer-to-peer discussion and the degree to which the environment is full of belonging cues—how students listen carefully to one another, reference and build off of one another's ideas, and generally make each classmate feel like their words matter. As we noted before, an intervention designed to enhance socioemotional health only works if the environment emphasizes student well-being as much as the content does. As the video closes, Equel's students put gratitude into action immediately, writing letters to a teacher so they feel the benefits of expressing appreciation right away.

But, again, even a thoughtful reflection isn't enough on its own. Behaviors and mindsets are made habits via frequent application. A virtue becomes part of the fabric of a school community via repeated application and the magnification of constant signals that affirm its importance. The research on this is clear: the perception that something is a norm among group members is the biggest influence on motivation and behavior. Job one is ensuring that the institution and the people within it are always looking for examples of virtues and have systems to make them appear as visible and valuable as possible.

We'll discuss that idea more in a moment when we discuss the “mechanisms” of culture building, but we pause here to note that encouraging students to demonstrate virtues allows them to feel the positive emotions that accompany positive (i.e. virtuous) behaviors. The fact that being “virtuous” generally feels good is often overlooked, but for the most part humans have evolved to feel good when they demonstrate virtuous behavior. Generosity feels good to most of us because it benefits the groups we have evolved to rely on and cements our connections to them. We have evolved to find it gratifying so that we are more inclined to do it. So helping students to engage in positive prosocial behavior is likely to make most students feel good about themselves, to recognize the parts of themselves that are already virtuous, and to enjoy the feeling of contributing to and being appreciated by the community. Students themselves are often not aware at first of how positive and affirming this feels. In fact this is a topic good virtue instruction can subtly draw students' attention to. You could add a question to a reflection on gratitude such as the one we were describing earlier that asked something like: “Think of a time you expressed gratitude to someone whom you are close to. How did you feel afterwards?” Or similarly, with a virtue such as generosity or compassion or honesty: “How did it feel to you afterwards?”

Of course, not every single student will feel good about engaging in virtuous behavior. There will always be people who show less desire to demonstrate positive behaviors and invest in shared well-being, but the number who do engage positively once they experience how it feels to do so in a community that values it may surprise you—and them! Most young people want to feel belonging. They want to feel like they are contributing members of a worthy group. They can be convinced otherwise; they can seek belonging in counterproductive groups and take on antisocial behaviors, but for the most part we think that if we—and other students—model, explain, and show appreciation for prosocial behaviors, most young people will choose to seek them.

We sometimes think of character as fixed—that a student who behaves a certain way just is that way he is. But like anything else, people (young people, especially) change as the cultures around them exert influence. They “progress … through a trajectory,” as the Jubilee Centre puts it, which begins with their understanding virtue and then experiencing it and responding to incentives—both intrinsic and extrinsic—to make a habit of it. Ideally this process feels good, and over time virtues become for them “autonomously sought and reflectively chosen virtue.”

THE CASE FOR GRATITUDE AND RESILIENCE

We love the way Equel Easterling made a virtue meaningful in the lives of his students. We love the way his classroom communicated belonging to students in the way they interacted with one another as they discussed virtues. But we also love his specific choice of virtue gratitude. Arguably he chose the single most important virtue of them all.

We've noted the necessity of making choices among the virtues to build into a school's culture. Five to seven is our target number. And that means hard choices. The list of potential virtues is long. So we want to make the case for a few virtues that we think are especially beneficial to student well-being and belonging. In fact they're so important that we think schools should find a way to make them a part of their culture in durable and meaningful ways, even if they choose not to pursue a virtue-based character education approach. As we noted previously, there is quite a bit of science on the drivers of well-being and happiness. There's also quite a bit of science on what causes people to overcome adversity. In that research these two concepts rise above the rest.

Gratitude, as we discussed briefly in Chapter 1, is underrated. A recent publication by Harvard Medical School noted that it is “strongly and consistently associated with greater happiness. Gratitude helps people feel more positive emotions, relish good experiences, improve their health, deal with adversity, and build strong relationships.”9 The direction of the benefit is in some ways unexpected. We presume that showing gratitude is primarily beneficial to the recipient, because showing someone appreciation makes them feel special, more important, more valued. The surprise is that it is even more beneficial to the person expressing the gratitude.

Expressing gratitude regularly has the effect of calling students' attention to its root causes: there are good things in their world worth appreciating and giving thanks for. And then one of the most durable findings of social science kicks in: “Scientists estimate that we remember only one of every one hundred pieces of information we receive and the rest gets dumped into the brain's spam file. We see [and remember] what we look for and we miss the rest,” Shawn Achor writes, “and what we look for is a product of habit.” Students who look for good things in their world see more of them and find the world looks like a more supportive place with a clear place for them in it. After a while this becomes a habit, Achor notes. He calls it the Tetris Effect. Like a chronic player of the video game Tetris, who starts to see its component shapes everywhere, students who practice looking for things they can appreciate and who articulate why those things are worth appreciating start to see reasons to feel good about their world everywhere. By thinking about why those things are worthy of gratitude, they come to understand better why some things are valuable in life. This becomes more or less automatic (a “cognitive afterimage,” Achor calls it) and a kind of optimism is instilled.

This is often accompanied by physiological benefits such as a reduction in blood pressure, Emiliana Simon-Thomas, science director at the Greater Good Science Center at Cal Berkeley notes. It can “slow the heart rate, and contribute to overall relaxation.” Gratitude she says is a “de-stressor” that sooths the nervous system.10 And of course it builds social connections to bond and appreciate one another. Social connections are one of the healthiest things people can have; people with stronger, more positive social connections are routinely healthier physically and live longer. Achor writes:

“Few things are as integral to our well-being. Consistently grateful people are more energetic, emotionally intelligent, forgiving and less likely to be depressed, anxious, or lonely. And it's not that people are only grateful because they are happier. Gratitude has been proven to be a significant cause of positive outcomes.”

So when we observe Equel asking his students to write letters of appreciation, they—not the receiving teachers—are actually the ones whom the exercise benefits. It helps them to notice the people in the world who seek to help them. It causes them to feel like the world—or their world—is on their side. From where they're sitting, it seems like a better place.

Back in 2016, on a visit to Michaela Community School in London, Doug observed an example of an exercise in building gratitude. In retrospect, its benefits to students' socioemotional health are even clearer than they were at the time. At the end of lunch, a teacher stood and offered pupils at the school the chance to stand and express gratitude for anything they felt was important in front of the gathered group of students (about half the school). It's important to note that it was entirely voluntary. No one was required to say anything. They were not told who or what they might want to show gratitude for. It was an example of “virtue reasoning.” Students decided for themselves whether they wished to express gratitude to someone, and if so, for what. And most of them did. Their hands shot into the air. Almost everyone in the room wanted to be chosen to say thanks.

Was this perhaps because, having made a habit of doing so daily, the students felt the psychological benefits? Were they responding to the fact that it made them feel happy and, well, virtuous? Contributing members of the community? Did it feel adult and mature to have the wherewithal to throw off the narrow lens of childhood (it's all about me) and embrace the people in the world on whom you relied? To affirm the presence of a village around you?

Whatever the reasons, students stood and thanked their classmates for helping them study. They thanked their teachers for expecting a lot of them and helping them. One student thanked the lunchroom staff for cooking for them—the school ate family-style meals with real cutlery and plates and (as we discuss in Chapter 2) this resulted in real face-to-face conversations. For a person used to US school meals eaten in the blink of an eye off plastic trays, it was eye-opening, a ritual that clearly built belonging and reinforced social skills.

Given how strongly many people hate speaking in front of large groups, it's worth noting that each of these eagerly proffered expressions of thanks was made impromptu and while standing in front of more than a hundred people. And yet the gratitude seemed to come pouring out of them until the teacher in charge said it was time to go back to class. The ritual seemed to give the students who spoke a sort of stature. It expressed the idea that the appreciation of a student like Havzi or Camilla, when earned, was important enough for a room full of people to hear about and take note of. Part of the message was that their appreciation, their opinion, was a valuable and important thing. No wonder there were more hands than the staff could ever call on.

Doug wrote elsewhere about how unexpected it was:

“I found myself wondering about it for a while afterwards. Here were kids … who might have faced difficulty at home and on their way to school. Many had left (or even lived still in) places racked by violence and difficulty. But … their days were punctuated not by someone reminding them that they had suffered or been neglected by society, but by the assumption that they would want to show their gratitude to the world around them.

“What did this mean? Well, first of all, it gave rise to a culture of thoughtfulness. Everywhere I looked students did things for one another. In one class a student noticed another without a pencil and gave her one without being asked. In the hallway a student dropped some books and suddenly three or four students were squatting to pick them up. When students left a classroom they said, ‘Thank you’ to their teacher.”

It wasn't just that everyone seemed to be thanking everyone else and seeking to do something worthy of gratitude. They seemed to take pleasure in it. Many students chose to say “Thank you, Miss” or “Thank you, Sir” to their teachers as they filed out of the room after class, but the tone was always cheery. Students bounced out of class.

In writing about the power of gratitude, Shawn Achor notes that the important thing is not just to name things you are grateful for but to say—and therefore think about—why. This causes you to think about the things you value most in the world. Thus a tiny detail from lunch at the Michaela School also sticks in Doug's memory. The teacher running the gratitude session occasionally gave students feedback. “That was excellent, Camila. You were very clear about why you appreciate how hard your mother works.” “Thank you, Havzi. Could you briefly say why Luke sharing his snack with you was meaningful?”

As we leave the scene in the school's cafeteria, it's worth noting a key framing of the psychologist Martin Seligman's work. Seligman found, we have noted, that happiness does not consist merely of pleasure. It consists of meaning and engagement as well. People who experience happiness consisting of all three aspects lead the happiest lives. What is true then of our grateful students is true of examples throughout the book. When people feel connected to other people and to something larger than themselves, and when they lose themselves in an activity or endeavor and when the things they work toward feel important—achievement or service or community or family—then they are happy, far happier, in fact, than if they ardently pursue pleasure and pleasure alone. Surely that has broader implications for SEL lens work.

It's worth sharing a bit more about Seligman himself here. He is the founder of positive psychology, a branch of psychology that looks to study why things go right in some people's lives. Prior to Seligman and a few colleagues making the case, psychology focused almost exclusively on what goes wrong in people's lives, why it happens, and how to fix it when it does. Obviously that's important work, but it's only part of the story of humanity. What goes right is equally important. Rather than looking at what goes wrong when people struggle, positive psychologists want to know what makes them thrive, even in the face of difficulty. Of course there are students in our schools for whom we have to ask, “What's going wrong here?” But for the great majority of our students the question is: What can go right? What can enable them to thrive and flourish? What behaviors and habits and mindsets can we instill in them to make it more likely that they do so? There are a series of things we can do in schools to take on that latter challenge, and instilling gratitude appears to be one of them.

BUILDING RESILIENCE

Another key body of research in the annals of socioemotional well-being also has to do with studies of what goes right in people's lives, but in this case why some people respond with resilience when confronted with adversity or even trauma. Given how much students have been through in the past few years, it's doubly relevant now.

Columbia University Teachers College clinical psychologist George Bonanno has written extensively on the topic, particularly in his book The End of Trauma: How the New Science of Resilience Is Changing How We Think About PTSD. Bonanno finds that people are strong and surprisingly inclined to resilience. This does not mean that they do not suffer and struggle emotionally in the face of adverse experiences. Being upset after a difficult experience is normal and recovery often takes time, but Bonanno stresses that most people do recover, even from highly adverse events. Of course some do not; of course we need to be ready to identify those cases and provide them with access to the care they need, but the message of resilience is also clear: our children are strong. The great majority will overcome even extreme difficulty and it's important to remind them of this, and not suggest that we think they are fragile or damaged by their experiences. In fact, Bonanno's research suggests, most people follow what he terms the “resilience trajectory,” a common path back from adversity or duress.

Bonanno is realistic about the research on resilience and overcoming trauma and the limits of what it can tell us. We only know a little about why some people bounce back and why some struggle for more prolonged periods or perhaps never quite get over a terrible experience. There's more we don't know than we do know, but at the core of the ‘resilience trajectory,’ the path back from adversity Bonanno finds—an idea called the “flexibility mindset.” People who have this mindset are the most likely to thrive after hardship. People with a “flexibility mindset” tend to share “three interrelated beliefs…optimism about the future, confidence in [their] ability to cope and a willingness to think about threat as a challenge.” It is “essentially a conviction that we will be able to adapt ourselves to the challenge at hand, that we will do whatever is needed to move forward,” he writes. “These beliefs interact and complement each other in a way that multiplies their individual impact. And collectively they produce a robust conviction…‘I will find a way to deal with this challenge.’”

If we can instill a flexibility mindset in people who have faced difficulty, Bonanno argues, we give them the best possible chance to return to a state of well-being and flourishing. As with gratitude, we think weaving the component parts of the flexibility mindset (and thus the resilience pathway) throughout school cultures and magnifying the signals that reinforce it are critical actions for educators to take.

One key additional piece of research on the topic of resilience comes from Bonnie Benard, a social worker whose books include Resiliency: What We Have Learned and Resilience Education. Benard notes that the environment, not just the individual, plays a role in responses to adversity. There are in fact “protective factors” in certain environments that increase the chances that people who are part of those communities will thrive and show resilience in the face of adversity. “The characteristics of environments that appear to alter—or even reverse—potential negative outcomes and enable individuals … develop resilience,” Benard writes, are, first, the presence of “caring relationships.” These relationships “convey compassion, understanding, respect, and interest, are grounded in listening, and establish safety and basic trust.” The second thing environments that promote resilience do is send “high expectation messages.” That is, they “communicate not only firm guidance, structure, and challenge but, and most importantly, convey a belief in the youth's innate resilience.” Lastly, organizations that foster resilience give young people “opportunities for meaningful participation and contribution” that includes bearing “real responsibility, making decisions, expressing opinions and being heard.”11

Reading Benard's description, we are struck by its applicability to the classrooms we portrayed in Chapter 3. They are learning places and they are “protective” places. Teacher relationships “convey compassion, understanding, respect, and interest” and so, interestingly, do peer-to-peer relationships. They certainly manage to send “high-expectations messages” consistently. They are full of firm guidance, structure, challenge, and belief. And again they clearly give young people opportunities for meaningful participation and contribution. Students have voices but perhaps most strongly of all feel heard.

The characteristics of protective places Benard describes give us a pretty good recipe for how a good school or a good classroom should run, and so again one of our takeaways is that in addition to the many things we also do, running a great school and a great classroom is also critical to positive mental health for young people. Doing our core work exceptionally well is a key part of what it's going to take to help students thrive.

HOW A MOMENT BECOMES A MECHANISM FOR DEVELOPMENT

During the pandemic, Hilary's family adopted a few regular traditions and rituals, one of which was playing a game where family members drew a card with a written question on it. Everyone around the table answered aloud. Some of the prompts were simple (What's your favorite season?) Others presented more of a challenge (Who is the funniest person in your family?). Hilary quickly realized that much of the “challenge” was socioemotional in nature, managing the human side of answering. Beyond the question Who really is the funniest? are considerations like: “If I answer truthfully, what if I hurt someone's feelings by saying they aren't the funniest? Do I fib? Do I not answer the question? I could say, ‘Oh, everyone is funny,’ but that's really the same as saying nobody is. What if I say I think I'm the funniest? Then what will people think of me?”

As time rolled on, and more and more of these conversation cards were pulled, it was not lost on Hilary how the discussions they evoked were lessons in how we understand, model, and develop character. In those dinner conversations her family wrestled with issues like honesty, fairness, and courage. A simple game provided practice and experience exploring family members' values, how they would or could exhibit virtue and model character in their daily lives.

But even more than that, the questions provided the opportunity to learn how to navigate the dynamics of relationship building and connection through frequent, low-stakes opportunities at trial and error. There were small but not always simple interactions amidst a group where safety and caring were established. Actually no one got upset when I said someone else was funniest. They took it as an opportunity to celebrate that person too. Hmm, people didn't think it was that funny when I said it was me.

Low-stakes trial and error in a supportive environment is a very powerful thing for learning to make your way in the world.

While these moments happened at home, they are typical of how recurring events can become an opportunity to develop the building blocks of interpersonal skill or character. The daily game became what we call a “mechanism”—a recurring setting in which questions were raised and reflections about self were normalized. Schools with strong, vibrant “protective” cultures tend to use such mechanisms especially effectively, particularly when they can infuse them with a sense of community, belonging, and psychological safety.

A “community meeting” is one of the most common—and for our money, effective—mechanisms a school can leverage. “Meeting” is a time when a large portion of the school—ideally the entire “village”—comes together; such times are perfect for stressing togetherness and reinforcing shared values, especially those values that help young people thrive and connect. If we share a culture, if we are a village, there should be times we all get together to talk about what matters most.

Scheduling short, well-planned schoolwide, gradewide or even single-classroom “meetings” is powerful in part because we can all see one another. A village conceives of itself as a village in many ways because there are times when everyone turns out for an event, when everyone can see each other. It's even more powerful when there are rituals and traditions—we greet each other in a consistent way. Or we dance, sing, or tell stories. Taken together this says, “We are an ‘us.’”

Here, for example, is a picture of one of our favorite principals, Nikki Bowen, at morning meeting with her students at Excellence Girls Charter School in Brooklyn, New York.12 Students are gathered in the school gymnasium. Teachers, sitting beside students, are engaged in a chant or song, a ritual that occurs frequently at meeting. Nikki is walking toward the center, getting ready to orchestrate the proceedings.

Notice the way students are seated. They are in groups by homeroom and in tidy rows. This manner of seating suggests the intentionality and importance of the meeting. It's carefully arranged because it matters. And students can all see one another—it helps to see “us” to conceive of “us”—and be seen. Yes it's also true that it's easier to create an orderly happy productive environment when you can tell at a glance that everyone is seated where they should be, but mostly the arrangement is about feeling seen and heard by everyone. You can raise your hand to speak and everyone can see you. Each class has its own place to sit. (Having a place means you belong!) There's space in the middle for people to be invited forward to share ideas or be honored or perform in some way. It's a shape built for “togetherness.” Nikki circulates, talking values, cueing songs, and asking questions of students. She regularly uses “meeting” as an opportunity to call out class groups and individual members of the community for special praise.

It's not just Nikki talking, though. Other teachers often lead at meeting. Sometimes students do. And no matter who is leading, the rest of the community participates actively, often via Turn and Talk and Call and Response. It looks and feels like Jen Brimming's class from Chapter 3 but at 10 times the scale. And there's a lot of singing: the Hope Chant, the Respect Chant, the Optimism Song. “We woke up the neighbors each morning with our school pride and togetherness,” Nikki recalls.

Here are the words to one of their school songs. See if you can spot the themes that recall the ideas in Chapter 1:

This is the school that has the girls who work hard all day long!

We're great thinkers, dynamic speakers

And we will change the world!

How will you change the world?

By being my best self!

Your best what?

My best self!

But it only takes you?

No it takes me, it takes you, it takes all of us, it takes our sisterhood.

Cuz girls are … smart, girls are strong,

Girls are helpful, girls are special, girls are POWERFUL!

Morning meeting is short, by the way: 10–15 minutes, sometimes less. But you can get a lot done in a short time when you have clear goals and familiar, well-established rituals.

You could use the meeting to ask students the sequence of gratitude questions we shared on page 138, for example. Or you could also use it as an opportunity to reinforce a virtue like, say, consideration. Doing that at meeting might sound something like this:

Before we head to class, I want to share two small examples of consideration I saw among students this week. One was a tiny moment many people might not have noticed. On Wednesday, I noticed a student in seventh grade drop his binder in the hallway. His papers and things scattered but it wasn't a big deal because right away and without being asked, three or four classmates helped him gather and organize his stuff. By that I mean they didn't just hand his stuff back to him, but they helped put pages back in order and held one set of notes while he put another back into his binder. I noticed Anthony Watkins, Desi James, and Lucia Rodriguez, and I know there were others. Thank you to those I recognized and those who were just as helpful but I wasn't able to see in such a thoughtful group. Two snaps, please, for those community members whose consideration made this a more supportive place to go to school, a place where you always know you can rely on your classmates.

But consideration can also be intellectual. So I just want to describe briefly the discussion I heard in Ms. Breese's grade eight history class. The topic was the Bill of Rights, and more specifically what was guaranteed to citizens under the Second Amendment. People did not agree, as is common in a democracy, but Ms. Breese's students did an exemplary job of both listening carefully and disagreeing respectfully. I heard lots of students say things like, “I see your point but …” David Lopez even summarized a classmate's argument that he didn't agree before he added, “But I'd like to give another interpretation.” It was an exceptional example of how we can disagree and also remain a respectful and connected community. So two stomps on two for Ms. Breese's fourth-period grade eight history. One-two!

We've written out these hypothetical scripts in detail because we think the specific words and framing matter, and because we think that's how a great school leader would do it. The purpose in this case is both to “catch” students exemplifying school virtues and to make meaning of those events. Catching virtuous moments is nice. Catching them and having a great and positive setting in which to share them is better. That's the power of meeting or some other mechanism. With a good place to celebrate them, now you have an incentive to go hunting virtues.

As our examples above imply, we especially love it when school leaders call out tiny moments that might otherwise have gone unnoticed. It's important to help students see how those actions make the school better and more welcoming for everyone. We want to make it more likely that positive actions get noticed and that students understand the value in them. And while our example is from a schoolwide meeting, it could just as easily come from a grade-level meeting, or one held in a single classroom.

Another detail about the examples above: we ended them both with the larger “village” giving affirmation, in this case in the form of snaps, stomps, or claps. We think it's important to add something symbolic to show that the whole community places value on the actions, not just the person speaking. That's one reason we love “two snaps” or “two claps” or “two stomps.” They're fast and physical ways we can have the school community express affirmation of people and give its blessing to an idea. Since those affirmations get used a lot, just snaps alone are not enough (as they were in Chapter 3). In meeting you need to be able to mix it up: “Two snaps and two stops for Abed!;” “Two claps and an ‘Oh yeah’ for Desiree.”

Though as we've mentioned, “meeting” can be done at a grade level or even in a single classroom, it's ideal when it connects students across levels of the school and makes what feels like separate groups feel like one. When Denarius interviewed a group of students about what they liked and valued about his school (described in Chapter 1), he was surprised to find that 1) students loved meeting, and 2) what they loved most was the chance to see and interact with students from other grade levels.

There are a variety of ways to do “meeting” in other words, and a school doesn't have to choose just one. “We have community circles to build connectivity across a single grade-level and use a schoolwide Friday celebration to honor student leaders in front of the whole school every Friday,” one school leader told us. They use a series of meetings with differing groups joining for different purposes. One theme we'd point to is that quality is more important than length. You want meetings to pop with energy and positivity. You want people to leave wishing it was a little longer. Don't belabor things. If there's more to say on a topic, bring it back again at the next meeting. If a meeting expresses our values, those values should include honoring people's time and planning things carefully.

Another way to acknowledge students who show character and virtue would be to create a simple and symbolic icon: a laminated heart made in the school colors or a picture of the mascot, for example. A school leader could say, “I'm going to put the green and gold heart on the wall outside Ms. Breese's class this week in appreciation for what I saw.” Or “I'm going to put the Hawk's Crest in the spot in the hallway where those students were so helpful.” Now the school has a very simple system for describing virtuous behavior (morning meeting), a system for the group to express approval and appreciation (stomps, claps, etc.), and a third tiny, simple system for helping people remember them and placing additional appreciation on them. It has built a series of butterflies, to use Joe Kirby's phrase.

VISUAL CULTURE

The idea of putting an icon—the Hawk’s Crest—outside a teacher's room or in a hallway to honor the values expressed there is a great example of another crucial mechanism for reinforcing character and belonging: visual culture. The walls can talk too—and schools can design them in a way that speaks the language of virtues and values. Including quotes from current and previous students, images of students doing virtuous things, or quotes from key members of the community are typical ideas. Happily they are butterflies—extremely low-lift actions, great for a leader to delegate to a group of teachers who love this kind of thing—but have huge influence on creating a warm and supportive community.

Consider the impact of what one school we know did. They placed a large printed photo of each student with their first name at the bottom in the front hallway: name plus face. So simple. Suddenly it was ten times easier for both adults and peers to use students' names. One of the simplest ways to show people they belong is to call them by their names. If the school secretary knows your name, if the custodian knows your name, if the fifth-grade teacher knows your name even though you're in fourth grade, you feel known. And of course it's also a great memory refresher for adults. See a student and realize you're unsure of his or her name? Dash on over to the picture wall and doublecheck. Next time, you're sure to remember!

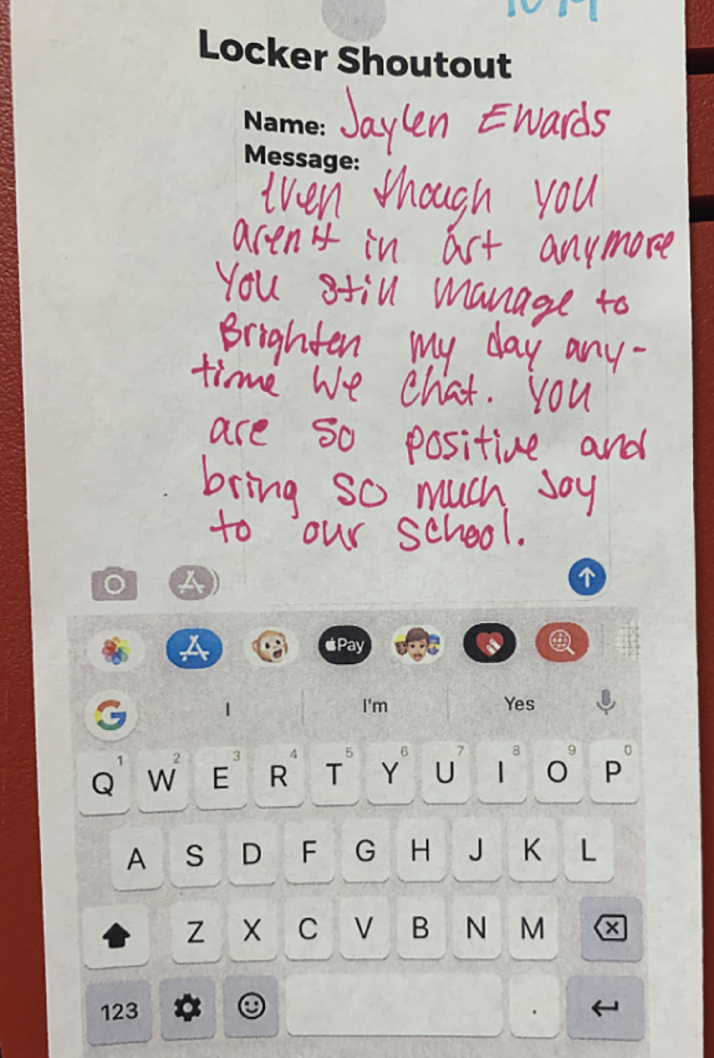

Or consider something we saw on a recent visit to Memphis Rise Academy in Memphis, Tennessee, where we noticed a system called Locker Shoutouts. Members of the community can grab a tiny appreciation form that looks like the one shown in the photo. On it, they write a short appreciation that they attach to a student's locker. On our visit we noted a student named Jaylen had received a note from one of his teachers expressing appreciation for his enthusiasm in class.

It's a simple system that makes it easy for the good things to be appreciated and made more visible. In addition to Jaylen finding the note on his locker seen here, another student, Sarah, had written an appreciation to a classmate, Magda, for helping her figure out a math problem at lunch. Yes, Magda must have felt great returning to her locker to find the small token of gratitude. Yes, Jaylen must have felt a keen sense of belonging at the school. But so too Sarah must have felt good to be able to show her appreciation. And think also about how the students in the school see the world differently, wandering down the hallway and noticing lockers dotted with appreciation for the goodness members of the community are constantly demonstrating. It makes the school feel like a more positive, welcoming, and supportive place. And since our perception of group norms is the most important driver of our behavior and motivation, it encourages students to seek to match those positive and healthy norms.

Notice, by the way, that Locker Shoutout is printed with an image of a keyboard at the bottom. That might seem strange but it's a subtle hint. Elsewhere we discuss the importance of teaching students positive social media habits. The keyboard suggests to students: This would look just as good on your phone. This is the kind of thing that you could post to build a positive and supportive online community.

And in fact, social media skeptics though we are, we think a school could experiment with an electronic version of the locker shoutout that could make the goodness of community members even more broadly visible and could model for students how to use social media to show appreciation rather than to denigrate.

As a principal, Denarius spent a lot of time planning out visual culture. Here are a few examples of how he used it to build culture at Uncommon Collegiate Charter High School.

At the top of this image, you can see the virtues Denarius's school has chosen. They're visible throughout the school but here are paired with images of people who've exemplified those virtues and whose stories students are familiar with (they talk about them at meeting!). In addition, taking the time to post honor roll students shows the importance of academic achievement. Notice that the materials are carefully posted, perfectly spaced and aligned, and the walls are clean and tidy. This expresses the idea that we value what is posted.

Lots of schools post quotes from famous people. We like that too. But we love the idea of this quotation from one of the school's alumni.

Or check out this wall: another beautifully framed quotation from a graduate and a colorful board where people can say “thank you” to staff members. It's a triple whammy: it's beautiful, it gives students the gift of sharing gratitude, and it makes teachers happy and motivated and appreciated. It's easy and appealing to do something good for the community and good for yourself!

THE MECHANISMS OF WIRING

We've talked about what to talk about with young people to help develop their well-being (virtues! gratitude! resilience!) and shared a few examples of when and how schools might engage those conversations (meeting!). But as we've mentioned, conversations about beneficial mindsets and habits are best when they're woven into the fabric of the school—when, like belonging cues in the classroom, they are constant small signals.

So here are a few more times and places that can be harnessed as culture building mechanisms in service of SEL development.

Arrival

Check out the video Shannon Benson: Good Morning in which Shannon, then the dean of students at North Star Academy Clinton Hill in New Jersey, and his colleague, Anneliese Tint, greet students and parents at the door in the morning. What could better remind you that you belong than being welcomed with a warm greeting and a handshake? In most cases Shannon greets students by name (in a few more weeks he'll have them all). There are also short greetings and interactions with parents. It's a great way to build relationships and make sure parents feel welcome too.

Here are some types of interactions we see:

- Small playful moments: Shannon jokes with Johnny about his water bottle.

- “Everything okay?”: Shannon checks in with one boy to make sure everything went okay after school the day before.

- Practical details: Shannon takes the opportunity to walk over to a student's car to check in with Mom about a missing permission form. So much better than a phone call!

- Tiny reminders about culture: Shannon subtly reminds Johnny how to greet an adult by saying, “Good morning, Johnny,” in a deliberate tone. He's calling Johnny's attention to the fact that he is modeling the greeting he expects back.

- Teachable moments: One girl is welcomed back warmly, but Shannon asks what she needs to say to her teacher about her behavior the day before. She cheerily replies, “I'm sorry,” and Shannon affirms that whatever happened yesterday has not diminished her in his eyes. (“That's not who you are.”) He explains why it's important to take responsibility and they high-five; she is happy to make amends and be back to normal. Note also that the student's mother is aware of the incident—they've talked about it by phone—but Shannon reassures her that everything is okay.

Honestly, the whole arrival feels like a scene from a village in a bygone era, when community courtesy and connection were stronger, more prevalent, more central to people's lives.

There are a thousand ways a school could use arrival to shape culture, set expectations, and build belonging. Recently, for example, we watched Dan Cosgrove, principal of Uncommon's Roxbury Prep Middle School, greeting students as they arrived. He stood at the school's front door and welcomed students by name. He showed students several positive self-talk phrases reinforcing resilience he'd printed on a card and asked them to choose one of the phrases and think about a time when they could use it.

Arrival, in other words, is an ideal time for building community and shaping healthy mindsets—it's a mechanism. It allows staff members to connect and build relationships and set the tone for the day. (Note the handshakes and eye contact; notice that as Shannon and Anneliese greet students, they greet them back.) It's just the sort of social skills students didn't practice during the pandemic and don't practice when their lives migrate online.

Meals

Meals are another ideal time to shape culture. Eating together is a time of meaning and importance in almost every culture and faith. We tend to pray at meals. We invite people to eat with us as one of the deepest signs of welcome. We celebrate by feasting.

And in fact, we've seen several examples so far of how schools have harnessed meals to express culture.

Earlier we saw how London's Michaela School used the end of lunch to create a public setting where students could express gratitude. There were more details to the meal that built culture, though. Students rotated responsibilities like clearing plates, bringing over the meals, and pouring drinks out of plastic pitchers. The meal was family style, and students and teachers chatted meaningfully while they ate. And the school also often wraps up a lunch with communal recitation of poetry. It's a powerful moment intellectually. (Student are proud to know the poems by heart and prouder yet to be able to quote them to you.) To hear and to join with a hundred booming voices reciting in unison is a powerful experience.

In Chapter 2 we saw how Cardiff High School used the informal time after lunch to allow students to engage informally in a variety of ways to build atrophied social skills: chess and table tennis and cards. Marine Academy also used family-style meals. It's worth noting that if it seems expensive or logistically challenging for schools in the US, communal meals don't have to happen every day. They could be on Fridays, or the days before vacations. Or there could be a “principal's table,” where students were invited on a rotating basis or could earn the right to join based on the exemplification of character.

Breakfast also has the potential to serve as a culture builder. Stacey Shells Harvey, CEO of ReGeneration Schools in Chicago and Cincinnati, quickly recognized this need post-pandemic. During the first days of return, students were required to sit six feet apart, as in so many other places. They were masked. Only so many students could be in any given space at a time, so breakfast moved to classrooms. There was a lot of logistical talk about getting and returning trays and milk cartons. In such an environment, informal conversation withered. Perhaps this sounds familiar.

But the odd silence remained, even when masks came off and desks moved (slightly) closer. Stacey noticed an awkwardness during breakfast; there was still almost no morning chatter. And she noticed that some kids would be searching the room with their eyes for a connection they didn't know how to start. So she implemented an idea called “Breakfast Questions,” written by teachers on a rotating basis and approved and reviewed by administration. They're posted each morning in the classroom, three per day, for students to discuss. The questions are engaging and interesting, a combination of playful and slightly more serious:

- Which make better pets, cats or dogs?

- Agree or disagree: the book is always better than the movie.

- Who would be the best celebrity to hang out with and why?

- Agree or disagree: the world today is better than when your parents were kids.

- Should schools be able to punish students for mean posts on social media?

- Would you rather be the worst player on a team that always wins or the best player on a team that always loses? Discuss.

In Stacey's case, students discuss these questions as a whole class, but students could just as easily discuss them in smaller groups at cafeteria tables. The idea is to foster conversation and build social skills through daily practice. Her school also uses the Habits of Discussion technique discussed in Chapter 3, and the approach to discussion here works in synergy with that even if the topics are much more informal. Students look at each other, rephrase, and try to connect ideas. “It has to be volleyball, not ping-pong,” Stacey told us. “We tell the teachers, ‘Its kid, kid, kid and then back to you to ask another question—often in lieu of giving your answer. You want to keep them talking to each other.’”

Even games can be useful in fostering connection and building social skills. Elisha Roberts, chief academic officer of Strive Prep in Denver, Colorado, shared an experience she witnessed during the meeting of the school's speech and debate club. In the activity, sometimes described as group counting, students had to count out loud from 1 to 25 (or higher) as a group without an assigned order, without two people talking over each other. If two people said “eighteen” at the same time, they had to start over. The purpose of this activity was to heighten students' consciousness of their peers, develop patience, and work as a group to complete a challenging task. Success required reading nonverbal cues, establishing eye contact, and learning patience and cooperation. Elisha noted that students became aware of the social cues in the room, and that it helped students to build trust with their peers by cooperating and achieving something. They happily played it at the beginning of each meeting and it became a kind of tradition. Although this sort of game could be played anywhere, it seems ideal for something like breakfast or lunch.

Hallways

Impromptu meeting places can also be wired for connection. Hallways are a great example. One of the unusual features of Rochester Prep, a school Doug helped found, was tables in the hallway. The idea was that on a rotating schedule, teachers would sit at the tables during free periods, preparing lessons and grading papers. But part of their job was what was called “passive supervision” (“passive” for short).

The adults were just there quietly working most of the time, but it turned out that having them in the hallway changed middle schooler behavior. A student coming out of a classroom into an empty hallway behaves (or is tempted to behave) differently from one coming out into a hallway where his or her math teacher is sitting at a table 20 yards away, glancing up from the laptop to say, “Morning, Alex.” Being seen changes decisions about behavior. It is a subtle reminder that causes people to choose to do what is right.

Usually the teacher on passive would ask a student a question (“How are you, Alex?”) but also, “Where are you going?” or “Do you have a hall pass?” or something similar as well. And even though the tone was warm, these interactions still felt a bit off, like the first thing teachers thought of when they saw a student was whether they had a hall pass. It felt like a missed opportunity.

This raised a question for the staff: What should be the first thing teachers said to a student they saw and why? The answer was that the best response was for teachers to ask questions about the things students were learning. Message: I see you and I see a scholar. So teachers on passive (and those merely seeing students in the hallway at non-passing times) would try to do something like this:

Hi, Alex. What class are you in?

Oh, history? Love it. What are you guys talking about today?

Oh, the Civil War? Cool. Have you talked about the Battle of Gettysburg yet?

No? A lot of historians think it was the turning point of the war. I'm sure you'll hear all about it.

Or: You have? Cool. Such bravery, right? Question for you then: Why do historians say it was so important in shaping the outcome of the war?

Ok, one more question because I know you gotta go [pointing to bathroom pass] and get back to class, but let's see how you do. Within ten years either way, when did the Civil War start? Not bad! 1861! Look at you, you showoff!

Ok, good chatting. Get things done and get back to class quickly so you don't miss anything. And be ready for the Battle of Gettysburg. I'm sure Mr. Hassell will talk about it.

Okay, yeah. Let me know when he does. I might ask him to let me join class that day.

Or

Hey, there. You on your way to the bathroom?

Okay. Remind me of your name?

Oh, Alex. Of course! I'm getting older, Alex. You have no idea how many things I forget.

So listen, I'm quizzing people on their math facts today. You gotta get at least two to pass my table.

Yeah, I know, otherwise you'll be stuck here with me! Yuk, right?

Okay, let's start with some two-digit multiplication. Think you can do 15 times 11 in your head?

No? Okay, we'll start easier. First do 15 times 10. Okay, great, 150.

Wanna take a shot at 15 times 11 now? Yessiree, 165.

What about 15 times 12?

Okay. No more math problems for you, no matter how much you ask!

See you soon, Alex.

Oh wait … Alex!

What's 15 times 11?

165. Great job!

There were so many benefits to the arrangement. Fewer things went wrong in hallways between classes and the unspoken message throughout the school was this: When a member of the school staff sees me, their first thought is to treat me as a scholar. Students felt known and seen and teachers got to choose things to talk about that were an expression of themselves. (“I'm getting ready to teach this poem to my seventh graders. See if you can guess the title!”). One teacher posted a map on the wall so he could ask geography questions more easily. The result, to paraphrase educational consultant Adeyemi Stembridge, was kids connecting to adults through content. Young people found that learning things was a great way to build relationships with people around them.

The idea for worktables in hallways came from a reference in John McPhee's book The Headmaster: Frank L. Boyden of Deerfield. “In his first year,” McPhee writes of the book's subject, “he set up a card table beside a radiator just inside the front door of the school building. This was his office … because he wanted nothing to go on in the school without his being in the middle of it.”

The idea, in other words, started with the school leadership setting out to increase its own understanding of the daily life of the school—to be connected. First, they started working in hallways. (We spend a bit of time in this book criticizing the tech sector; here we pause to praise the rapid increase in laptop battery life they have achieved and the clear benefits to educators!) They found that they quickly came to understand the school a lot better. And they found that pausing every 50 minutes or so at passing times to greet or redirect or wave to or remind students in the hallway was beneficial in building relationships too. The idea worked so well that teachers were added to the rotation. It also helped establish a fair amount of mutualism among staff. It's harder to be the teacher who ignores students behaving poorly or being rude to a classmate in the hallway when you have shared responsibility for spaces beyond your own classroom.

The point here is that hallways, and the time students spend there, pose an opportunity for schools: it's overlooked time that could be used purposefully. The first step, we'd argue, is ensuring orderly hallways where respect among students is the norm. If that doesn't exist—if students fear the hallways or brace themselves for the negativity they will endure or dish out there—it's hard to feel a strong sense of community. One small trick that can help—at least in middle school when classes are almost all single-grade—is staggered passing times. The sixth graders from 10:31 to 10:37 and the seventh graders from 10:39 to 10:45. This gives you a smaller number of students to manage and so it's easier to shape the culture of interactions. Asking teachers merely to stand by their doors and “keep an eye on things” during passing time also helps in many of the ways “passive supervision” did.

What else could you do with your hallways? Could a teacher circulate with a daily quiz offering, a prize for the student who can identify, say, three countries on a world map or three pictures of world leaders? Could there be a display where students could pause to write notes of gratitude or appreciation? Could there be music playing from a small speaker with students who had exemplified school virtues allowed to set the playlist for the day (subject to approval of the adults, of course)? We're sure there are far more brilliant ideas out there. The key is to see hallways as a potential mechanism, a recurring moment that provides the opportunity to build character and positivity and belonging into the fabric of the day.

“Advisory,” a daily or weekly meeting with a small group of fellow students (often from multiple grade levels) and a teacher, is another potential mechanism. Advisory might start the day and advisors could take attendance or at least sit somewhere in the school—a cafeteria table, their office, or a bench in a hallway or at a period just after lunch—where students could “check in” to start the day or linger and chat briefly. It's much nicer—and more welcoming—to check in with a small and welcoming group sitting around a table than in a typical classroom. Alternatively, advisory could happen at the end of the week: a brief check-in to make sure all homework assignments are complete or perhaps even step back and reflect, in a journal or via a gratitude exercise (i.e. three things I'm grateful for and why), in a small group.

STRATEGIC INTERVENTION

Students' social skills have in general almost certainly atrophied as a result of both pandemic and epidemic, but for some students the decline has been steep enough that they will struggle to build effective relationships. For these young people, conflicts will be more frequent or go unresolved. Potential connections will wither. They will be present in school but far less connected than their peers, possibly even alone in the crowd because they lack the skill to engage their peers. Schools will have to be even more prepared than before to teach certain students to socialize, especially those for whom merely providing an opportunity to connect is not enough.

At one school we know, the most adept connector on staff—a dean of students—invites certain students to lunch in the faculty conference room in the main office—a place that feels special and grown up. Kids are invited to come for lunch and sometimes allowed to bring along a friend if they want. Typically, most of the invitees are kids who are doing just fine—thriving even—it's a mix-and-match kind of thing, which has the benefit of causing students to connect with peers outside their social group. But a few of the invitees are carefully chosen because they struggle to connect. They are, without knowing it, the reason for the lunch. The conversation is mostly lighthearted. Sometimes he prepares a few questions in advance (they are a lot like Stacey Harvey's Breakfast Questions). Sometimes he reads a short article from the news and invites students to discuss. But he's always working and shaping the conversation, trying to draw in the kids who need drawing in, trying to subtly remind the kids who need to interrupt less not to interrupt. He's super-intentional to model eye contact and body language. Sometimes he'll offer a bit of feedback: “That's interesting, David, but maybe Shayna would like to finish the point she was making first.” He's coaching social skills. Sometimes afterwards he'll pull a student or two aside and say, “You did a really nice job of showing your appreciation for Iyana's story,” or “I'm going to invite you back next week and I want you to try to see if you can join the conversation without interrupting.”

If students can benefit from guidance and instruction on the how-tos of face-to-face conversation, the same is true for online interaction. In fact, we think it's a productive move for schools to consider offering students simply useful guidance on how to use social media in a way that's least damaging to their emotional well-being. (This could be schoolwide or for students who struggle with it or are involved in situations caused by it.)

One of the reasons some researchers think social media can be so destructive to young people, for example, is the constant feeling of comparison it evokes. There's a friend at a basketball game. There's another at the beach. There's a friend in a carefully presented photo to make it look like she's having the time of her life at a concert. All that comparison to a selective sample of other people's lives can wear you down.

It's also hard to find out through social media all the things people are enjoying (or appear to be enjoying) that you were not invited to.

Might it be useful to be aware that the version of other people's lives you see online is distorted? That you should avoid using social media most when you are feeling down and therefore most vulnerable to feelings of exclusion? It probably can't hurt.