CHAPTER 4

Reframing strategy

Strategic design is the organisation’s principal creative and learning activity

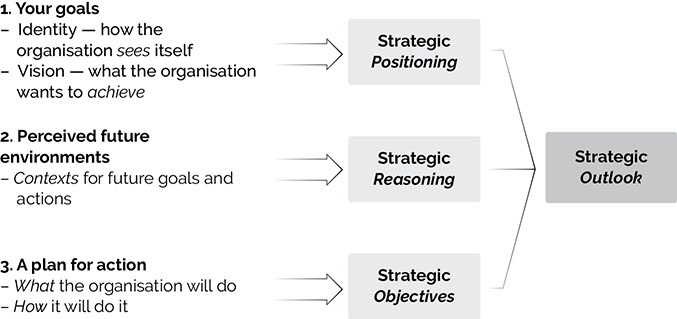

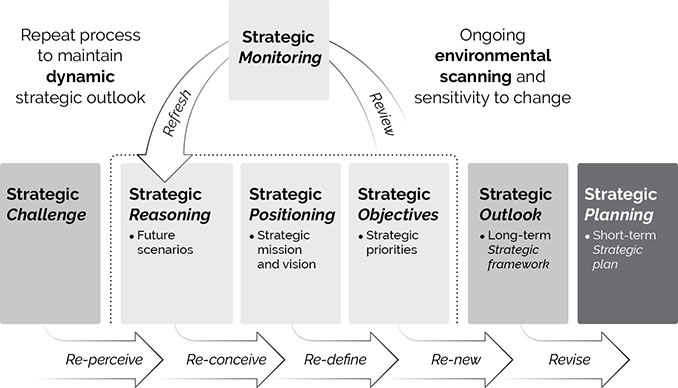

Organisations are poor at strategy. They treat it as an afterthought, something they’ll get to when time permits. Or else it’s an incremental planning exercise, a dour number-crunching routine or an inconvenient obligation that just has to be done. Of course, if you have these feelings of indifference or even disdain towards strategy, then you’re hardly going to invest any more time and resources into the process than you feel are necessary. Instead, the go-to approach for many businesses resembles the following: It’s hardly surprising, then, that organisations continue to be blindsided by unforeseen change when their strategy processes have been reduced to this cliché, focused on output rather than learning, creativity and originality. Companies adopt this approach because they don’t know any different. It’s an approach that results from a number of misconceptions that continue to limit the role and influence of strategy within organisations, namely: Strategy is not planning. Strategic design is about setting the organisation’s future direction and goals. It involves two significant creative steps: Strategising is about perception and conception. It requires imagination, creativity, innovation and entrepreneurialism. Planning, on the other hand, is about doing and getting things done. It’s about operations and implementation. Planning requires a different set of attributes: attention to detail, adherence to process and budgetary constraints. Planning is about operating within the broader context of the directional strategy; it is downstream from strategising. Strategist Gary Hamel makes his distinction between planning and strategising pretty clear.1 He argues that, Planning is about programming, not discovering. Planning is for technocrats, not dreamers. Giving planners responsibility for creating strategy is like asking a bricklayer to create Michelangelo’s Pieta. And this distinction between planning and strategic design is crucial. It sets the tone for how, and by whom, strategy is developed. In the absence of such a distinction, strategic processes and participants continue to be misaligned with purpose, with the output simply reinforcing the dour stereotype of strategy and strategists. When strategy isn’t differentiated from planning, it is viewed as a dry, serious and arduous activity that focuses on number-crunching, data tables and forecasts. It then follows that the people best equipped to perform such roles are those with skills in such activities. And this is what many strategy teams resemble. There’s an unspoken belief in business that the development of strategy is the domain of some exclusive club, best carried out by the organisation’s ‘best and brightest’ behind closed doors. These people are chosen because of their industry experience or their MBA qualifications or, in the ultimate snub to strategy, because they just don’t fit in any other department. What is obviously missing from this approach is an appreciation of the creative aspect of strategy development. While the process might be rigorous and appear sound on a spreadsheet, it is seldom likely to produce more than incremental strategic changes, the proverbial ‘last year plus 5 per cent improvement’. In a volatile environment, where the organisation needs to regenerate its strategic outlook, creativity should always take precedence over a dour, financially driven approach. When strategy development is viewed as a dour and incremental affair it often takes on an output focus, where the aim is simply to get the job done, to produce a document. It’s even seen as an inconvenient interruption to the real work of day-to-day activities — ‘This is something we just have to get through’. Companies that focus on producing output in order to meet their internal obligations are most likely to adhere to the clichéd approach to strategy development outlined earlier. In turbulent times, the purpose of strategic design is to generate a new and distinct strategic outlook that is fit for the future. In this environment, strategy development cannot be accepted as some obligatory exercise in incrementalism best performed by number crunchers behind closed doors. Instead, strategic design calls on the skills of creative and innovative thinkers, people with the imagination to conceive future change and the entrepreneurial ability to apply meaning to the organisation. Indeed, strategic design is the organisation’s principal creative and learning activity; it is the foundation of corporate entrepreneurship and innovation (see figure 4.1). Figure 4.1: layers of organisational creativity and innovation Strategic design, the process of generating a new and distinct strategic outlook, is the foundation of corporate entrepreneurship and innovation. Reframing strategy as a creative learning exercise in turn reconceives it as a process-oriented activity, rather than an output-oriented one. From this viewpoint, the purpose of strategic design is no longer to satisfy the internal requirement for a new document every three or four years. And rather than being done under sufferance, strategy formulation should be embraced with the same enthusiasm as any other creative or innovative exercise. The perception of strategic design as a creative learning activity is founded on five interconnected principles: Let me explain each principle in further detail. An all-encompassing strategic outlook represents the organisation’s holistic view of its future external and internal environment, its strategic reasoning, positioning and objectives (see figure 4.2). Such an outlook is the organisation’s unique fingerprint. Figure 4.2: the organisation’s fingerprint The all-encompassing strategic outlook is a corporate asset that cannot be replicated. Competitors may be able to respond to what you do, but they can never know the intricacies of your strategic reasoning — how you’re seeing the future environment, and why. This is why your strategic outlook is such a corporate asset. The quality of this strategic resource is ultimately determined by: Improvement in business performance begins with taking a resource-based view of strategy. Such a view values the company’s strategic outlook in the same light as its more tangible assets — its people, products, infrastructure, distribution networks and finances. In fact, given that the acquisition, development and use of other resources springs from this perspective, the strategic outlook sits alone as the corporation’s ultimate asset. Once it is reframed as a resource, the folly of treating your strategy as the product of a weekend retreat, or as the private domain of a select few, becomes obvious. Instead, like any valuable resource, strategy requires ongoing investment. It requires time and energy for development, resources for support and a process for optimal outcomes. It’s generally accepted that the essential activities of management are ‘decision making’ and ‘problem solving’.2 Indeed, senior management is the reward for consistently good judgement. So why do these same senior executives remain notoriously poor at foreseeing or responding to significant changes in their business environment? One argument is that managers have different skill sets from strategists, that their superior decision-making skills are incongruent with the creative aptitudes necessary to design strategies for the future. But I don’t agree. Decision making, like creativity, relies on forming a judgement based on stimulus. The problem lies not with the tradesman, but with the tools. When managers hear the word process their thoughts instantly turn to innovation gridlock, red tape, inaction and the like. ‘Only bureaucracies have processes!’ they insist. And it’s true, processes can stifle creativity and action. They can certainly test your patience. But just as often this perception of process as straitjacket is derived from the temporal exhaustion and need for instant fixes that result from a lack of corporate foresight — ‘We need a new product/strategy now!’ (refer to the section ‘Scenario benefits are too far away’ on page 23). No process, no matter how efficient, will survive the demands of such suffocating urgency. It doesn’t have to be this way. In fact, information overload and increasing business volatility have created the conditions in which internal processes have never been more important. And just as strategy should be viewed as an internal resource, so your process for designing strategy should be considered a dynamic capability delivering strategic value that is difficult to imitate.3 In particular, an internal strategy process becomes a valuable corporate asset when it unlocks latent or constrained business potential by enabling: Contrary to popular belief, these outcomes are not restricted to ‘sexy’, smaller start-ups seemingly unrestricted by process. Size doesn’t matter. It’s not the lack of process that enables entrepreneurs to seize opportunities earlier; it’s their lack of attachment to ‘what is’ and their ability to detect significance in weaker signals of change. Properly executed strategic processes are about unlocking entrepreneurial potential, not suppressing it. For an organisation investing in strategic design, this means embedding a process that is: This process is outlined in figure 4.3 (overleaf). Figure 4.3: an integrated and dynamic strategic process Such a process is an investment in the corporation’s ultimate asset, its strategic outlook. This approach to strategy design, with its emphasis on internal creativity, learning and collaboration, represents the company’s investment in its strategic resource. In effect, it’s an exercise in asset generation, beginning with one view of the world and the organisation’s position within that world, and emerging with an original and differentiated strategic outlook that is a better fit for the future environment. Such a process respects the prioritisation that strategy deserves, and produces the distinct outlook that company boards and shareholders demand. In March 2013 Domino’s Pizza in Australia undertook a major media campaign raising awareness of an impending announcement that was set to be the ‘biggest in 20 years’. ‘You’ve DEMANDED CHANGE and we’ve pushed ourselves to RESPOND,’ spruiked CEO Don Meij, the very public face of the campaign. Such was the weight of promotion that you couldn’t help but be intrigued by the upcoming ‘game changer’ innovation. Would we soon be receiving drone-delivered pizzas? Would eating more pizzas be the key to future weight loss? So what was all the fuss about? Why, the introduction of new topping choices and square pizza bases, of course. The consumer ridicule was instant and the feedback was clear: ‘What an underwhelming announcement!’ But really, should we have been so surprised? While Domino’s might provide a high-profile example, it’s hardly an isolated case of incrementalism dressed up as innovation. The fact is most companies struggle with strategic and innovation creativity. And the major factor behind this struggle is thinking that remains ‘anchored in the present’.4 Surrounded by the pervasive behaviours, policies and infrastructure of today, it’s nigh impossible to imagine new ways of working that aren’t ‘anchored in the present’. And without breaking free from today’s worldview, managers will always find it hard to innovate or to transform their business for the future in a timely manner. Anchoring restricts the organisation to repeatedly producing incremental, ‘faster horse’ strategies5, when a new type of thinking is required. We see examples of such incrementalism everywhere: doing things better within the current paradigm (cost cutting, outsourcing, shared services, reduced packaging sizes), rather than doing things differently to meet or establish a new paradigm. Overcoming strategic incrementalism therefore requires an escape from the overbearing context of the present. Scenarios hold the key to this perceptual freedom. To the uninitiated, scenarios can sometimes suffer from an image problem. They’re associated with risk management or safety first, ‘robust’ strategies designed to work across multiple scenarios. In other words, they’re seen as conservative, the Volvo of the planning world. And it’s true, scenarios are incredibly useful for highlighting risk and understanding uncertainty. However, their greater value lies in uncovering strategic options and innovation opportunities. I believe scenarios serve three purposes across what you might call a decision-making spectrum: a conservative purpose, a confirming purpose and a creative one. In turn, these deliver organisational benefits in the form of risk awareness, confidence to act and insight discovery (see figure 4.4). Figure 4.4: scenarios and the decision-making spectrum Scenarios serve several purposes, delivering strategic benefits to the organisation in the form of risk awareness, confidence to act and discovery of fresh insights. The conservative purpose is served in terms of risk minimisation, identifying and understanding future uncertainty. This purpose tends to be protective, akin to the new coach of a losing sports team saying, ‘Let’s get our defence right before we start building our attack’. But ultimately you need to score to win. And the other two purposes are far more attacking, more entrepreneurial. The first of these is confirming emerging thinking, providing the deeper understanding that supports previously held instincts and providing the catalyst that allows you to act with confidence. At a strategic planning workshop for an architectural design agency, scenarios were developed from which a strong theme of future suburban renewal emerged. In this scenario, local councils promoted policies to improve the proportion of residents who could work locally. As a result, community connection increased as people spent more time within their community and less time commuting to and from it. With reduced commuting, outer suburbs that were dominated by concrete and tarmac would begin to transition from a transportation culture to more of a village feel, with design placing greater emphasis on place and community interaction. For the client, future opportunities in urban design were obvious. ‘We need to increase our investment in this area. It’s something we’ve discussed before but never felt compelled to act on.’ The scenarios had confirmed their thinking. While the idea wasn’t new, their clarity was. The scenarios had provided the impetus to act. Freed from the constrictions of the present, scenarios open up strategic thinking by providing different, future contexts from which the organisation can approach its strategic challenge. This different backdrop is the essential stimulus for unlocking creativity and discovering new insights. Mentally unshackled from ‘what is’, managers are able to hold up a mirror to their existing operations and competencies and assess strategic responses from a different perspective. This is the transformational impact of scenarios: helping the organisation to reperceive the future external environment, and using these fresh perceptions as the basis for reconceiving the organisation’s identity, vision and objectives. This transformational impact is what makes scenarios so powerful. Suddenly strategies that have been historically successful, or that continue to be successful in the present, are no longer assumed to be the eternal truths they were. More importantly, new strategies emerge that were previously blocked by the boundaries of today’s paradigms. It’s the different, future contexts, allowing managers to develop new worldviews, that present these opportunities in a new light. Chapter 11 provides extensive coverage of a strategic planning project I facilitated during 2012–13 for the State Library of Victoria, ‘What is a public library in 2030?’ It’s worth noting here the transformation in thinking that scenarios enabled over the course of this project. Before the development of two scenarios for 2030, and based on the interview responses from multiple industry stakeholders, my initial thinking was that one of the key issues for public libraries concerned the future of digital publishing rights, a perspective framed by the historical paradigm of libraries and books and the growing popularity of ebooks. This issue, while clearly important, represents classic incremental thinking. The use of scenarios allowed new thinking to emerge that transcended the libraries as books paradigm. Suddenly, libraries could be legitimately conceived as creative hubs where content was generated as opposed to being managed and distributed, or as community hubs that facilitated active learning as opposed to passive content consumption. The issue of digital publishing rights consequently slipped down the order of importance as new, transformational strategic outlooks for public libraries emerged. Strategic design is about organisational learning. This is hardly a new idea6 7 8, but it was a concept I personally wrestled with for many years. Often during those times I was even dismissive of the idea, despite the fact that many of the scenario planners and strategists I most admired had written so enthusiastically on the topic. During those years I was an unconscious subscriber to the strategy as output school of thought. To me, strategy was about doing, organisations were about getting things done, and learning was something you did on your own time. When the penny finally dropped, it was a profound breakthrough for me. Of course strategy is about learning! It’s the learning that enables original insights to surface. It’s the learning that elevates strategy to a creative process. The learning that occurs during the strategy process is in the form of a deeper understanding of the ‘forces, relationships, and dynamics’9 driving changes in the business environment, and their possible future impacts. This understanding provides the platform from which new thinking emerges. Without this learning, it’s very hard to generate an original perception of the future and hence an original strategy. And this is the struggle in which many businesses find themselves today, having adopted a disempowering approach to strategic design that essentially outsources the learning component of decision making. Overwhelmed by the almost unlimited availability of information, managers instead rely on forecasts that have been filtered by the judgement of others: consumer demand forecasts, market performance forecasts and so on. In effect, writes Peter Beck, former planning director of Shell UK, managers have abdicated their involvement in the decision-making process ‘in favour of the experts’10: ‘In what respect is he then a decision-maker?’ he asks. ‘In fact, the real decision-makers are the people … who sift available information, assess the … situation, and take decisions.’ The result of this abdication in favour of forecasts is a lack of organisational learning, which leads to a lack of strategic creativity, strategic originality and strategic fit. Participatory strategic design enables learning because it requires managers to roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty; to exercise their own judgement in exploring the forces shaping their business environment. The emphasis here is not on surface-level outcomes, but rather on the forces driving these outcomes. In turn, this hands-on approach is empowering in that it enables managers to develop their own feel for the future. As for thousands of budding scenario planners, one of the first ports of call in my quest to better understand the method was The Art of the Long View by Peter Schwartz. This classic book had introduced scenarios to the masses since 1991 and appeared as a reference in most articles on scenario planning. So it was with great anticipation that I opened to the first page: ‘This book is about freedom.’ Cue my disappointment and confusion. Freedom? What an underwhelming opening, I thought. Scenarios aren’t about freedom. They’re about the future. What’s that got to do with freedom? It took me almost a decade to fully appreciate the wisdom of this opening line. Scenarios are about freedom. And the learning outcomes from creating scenarios provide this freedom. Having explored the factors influencing their operating environment, how these factors might evolve and their possible future impacts, managers emerge from the scenario process with a broader and deeper understanding of the environment in which they have to function and compete. In turn, this learning provides a liberating dose of clarity: In this sense, the organisational learning that occurs is empowering. Scenarios are about freedom. They allow you to act with confidence on the original insights you generate. In turn, this confidence provides another nail in the coffin of the stereotype of scenarios as a conservative tool for risk management. According to Peter Beck, in practice the opposite actually tends to be true: ‘The more the decision makers feel that they understand their environment, understand the dangers but also perceive potential opportunities, the more are they able to take riskier decisions.’11 ‘Most managers are “energetic problem-solvers” busy working in the “here and now” trying to “solve problems”,’ suggests George Burt in an essay reviewing Pierre Wack’s work. The problem, he argues, is: ‘Few managers invest in learning about those systemic structures that are the root cause of such problems that is driving their actions’12 (see figure 4.5). Figure 4.5: strategy as output In the absence of systemic understanding, organisations continue to be overwhelmed by problems in the ‘here and now’. The learning from scenarios ‘slows down change’. Rather, change still occurs at the same pace; it’s just not perceived to be disruptive or overwhelming, because the organisation is able to detect and make sense of it earlier and is rehearsed in its response. After all, it’s not the rate of change itself but the lack of preparedness for change that constantly leaves managers feeling out of breath. This effect of slowing down change can be likened to the different experiences of two drivers, an expert and a novice, approaching an intersection at 60 kilometres per hour. To the expert, the intersection approaches slowly; their perception of speed is moderated by a familiarity with the situation and their preparedness for what needs to be done. To the novice, on the other hand, the intersection approaches all too fast — the perceived suddenness of change stemming from a lack of preparation. With an understanding of the underlying drivers of change and their possible outcomes, the organisation is vulnerable to fewer surprises from external developments. In effect, it moves from the defensive state of perpetual responsiveness to a proactive position of anticipation and confirmation. Henceforth, surprises are subtracted from the future. You see headlines or issues or trends and you have an understanding of why they are occurring. While competitors continue to be caught unaware by unforeseen changes, you are seeing the unfolding of anticipated scenarios (‘That makes sense’), providing the impression that the pace of change has indeed slowed down. Of course, rehearsing the future is nothing new. Scenarios, simulation and visualisation have been commonplace for years in high-risk or high-performance fields where: Figure 4.6: who rehearses the future? Elite operators in highly uncertain, high-stakes, high-performance industries recognise the benefits of rehearsing the future. So why not corporations? The benefits of future rehearsal are undeniable in environments that are uncertain, involve high stakes or demand elite performance, where the aim is to make the future familiar. Of course, the military, the airline industry and professional sports are going to embrace scenarios, simulation and visualisation if they improve decision making and future performance. These operators are elite in their field and can’t afford to leave any stone unturned in the pursuit of better results. The characteristics of these future-rehearsing industries are not unique. Many can be applied equally to a competitive business environment. That the environment is uncertain is a given. The stakes are obviously high when decisions can have such an impact across people’s livelihoods and communities. And most successful business managers would regard themselves as high performers. So why is it that the vast majority of organisations still prefer to ‘play with reality itself’13, rather than learning from the safe house of scenarios? Slowing down change and the confidence that comes from making decisions in familiar situations are the business benefits from rehearsing the future. When significant changes do occur, you’re not overwhelmed or rushed. You’ve been here before. You’ve rehearsed your responses and their possible consequences. And because of this experience, you make better decisions. You know what to do when early signals of change arise. For the unprepared organisation, periods of significant transition are typically marked by confusion (‘What’s happening?’), uncertainty (‘What should we do?’) and reprisals (‘Who’s to blame?’). Caught by surprise, managers tend to react with hasty, inadequate responses that merely demonstrate their misreading of the situation, or else they are struck by strategic inertia, frozen by their inability to fully comprehend what is happening. Consider the actions of US car executives in recent years. In the wake of the financial crisis in 2008, and with their iconic companies facing bankruptcy, they flew to Washington in their private jets to petition the government, cap in hand, to bail them out. Unsurprisingly, they were scorned for being ‘out of touch’ by the public and politicians alike. The next time these industry leaders made their way to the White House they arrived in eco-friendly vehicles, belatedly determined to demonstrate that their companies were moving with the times. Or the Victorian taxi industry, which I discuss further in chapter 6. Rocked by the unforeseen emergence of Uber as a competitor, and perhaps unaware of the dearth of community goodwill, the industry decided to get on the front foot via a Twitter campaign. In an attempt to bolster their position in the minds of the community, and in a clear case of overreach, they launched a hashtag campaign called #YourTaxis, inviting the public to share their positive taxi experiences on social media. You can guess how that ended. After only a couple of hours, the campaign had to be shut down and the industry was no longer in any doubt about their customers’ dissatisfaction. What these examples demonstrate is that when confronted with unexpected circumstances, and in the absence of any future rehearsal, often the best you can hope for is to scramble your way forward. On the other hand, for the prepared organisation, discontinuities provide an opportunity for purposeful growth and a rapid gain in market share. Note: The significant strategic benefit of slowing down change is covered further in chapter 13. In an oft-quoted 1982 article in Fortune magazine titled ‘Corporate Strategists Under Fire’, Walter Kiechel III declared, ‘90% of organizations fail to execute on strategy effectively’.14 The authority of this relatively high failure figure has been debated ever since. Another feature on why business leaders fail, published almost 20 years later, estimated that in 70 per cent of cases the failure of CEOs could be put down to poor strategy execution.15 Whether 50, 70 or 90 per cent of strategies are poorly executed is beside the point. The fact is the figure remains too high and companies continue to be notoriously poor at implementing their plans. This poor conversion rate is strategy’s albatross, and I was reminded of this burden when preparing for a workshop for a large regional council: ‘Be aware’, I was informed, ‘that the CEO thinks most strategies are nothing more than a marketing exercise and that 9 out of 10 corporate plans are rubbish.’ So why does successful strategy execution remain such a problem? Perhaps the answer lies in how we define and subsequently treat strategy. When we think of strategy we tend to think of the act of strategic design, the formulation component of the process. Execution of this strategy is thought of as a separate activity undertaken by a different set of individuals. In other words, the two activities are treated as distinct — the thinkers do the thinking, the doers do the doing, and never the twain shall meet (see figure 4.7). Figure 4.7: the separation of strategic design and implementation Businesses have traditionally treated the activities of strategic design and strategy implementation as distinct, which has contributed to poor execution effectiveness. The result of this ‘artificial separation’16 is a lack of: Removing this schism, it would seem, is central to improving strategy execution. Why can’t the ‘doers’ be involved in the strategy design? Is there the implicit assumption that the implementers ‘aren’t smart enough’ or ‘don’t know enough’, and therefore any resultant strategy would be ‘dumbed down’? This view was made apparent to me when I was working with a CEO and one of his general managers in putting together a list of employees to take part in an upcoming scenario planning project. When the name of one employee was mentioned, the CEO briefly considered their involvement before shooting it down with the statement, ‘He’s not really strategic’. How condescending, I thought. As organisational learning pioneer Arie de Geus has said, ‘Brilliance is not a monopoly of a company’s top levels, neither is producing solutions the prerogative of specialists.’17 Perhaps for too long, too much emphasis has been placed on the primary design component of strategy, to the detriment of the secondary, equally important component, execution. After all, excellent design cannot overcome poor execution, and neither can excellent execution make up for any shortfalls in design. Strategic success requires that design and implementation be treated as equal and integrated components of strategy (see figure 4.8). And this means bringing the ‘thinkers’ and ‘doers’ together during the design stage. Figure 4.8: a participatory strategy process Strategic success depends on the integration of strategy design and implementation; they are not mutually exclusive. When strategic design and implementation are treated as distinct, communication of the strategy to the broader organisation tends to follow a familiar pattern: a briefing session is scheduled where those next in line down the hierarchy are informed of the new strategy; in a corporate form of Chinese whispers, attendees (the ‘chief implementers’) are then expected to brief their staff, and so on. In many instances, these meetings might condense months or even years of research, modelling and iterative conversations into a one-hour PowerPoint presentation. To expect that the audience, those responsible for putting this theory into practice, will be able or willing to grasp, remember or buy into the complexities, logics, implications and opportunities inherent in these presentations is a big ask. And yet this is exactly what is expected: ‘We’ve done our job — now it’s up to you.’ If company-wide strategic understanding, belief and ownership are so low, is it any wonder that strategic implementation is poor? In fact, while individuals vary in their ‘learning styles’, it is generally agreed that passive learning methods such as lecture-style formats are among the least effective modes from which people learn, and that more interactive methods such as group discussions or simulation (learning by doing) lead to higher learning and retention rates. And this makes intuitive sense; the more involved learners are in the activity the more likely they will be to remember and utilise the materials they have learned. Translate this theory to improving strategy processes within a company. Rather than being recipients of the completed strategy product, the ‘implementers’ would be active participants in its formulation. They would be involved in the conversations about external forces influencing their industry’s future. They would discuss the possible implications these forces represent to their company, and they would consider the organisation’s response. It’s from these conversations that shared learning, and a shared language, emerges. For the organisation, the result of such collaborative strategic design is a far broader base of understanding of the company’s strategic reasoning (‘I understand why we’re doing what we’re doing’). From this understanding springs belief (‘I have confidence in what we’re doing’) and ownership (‘I am committed to what we’re doing because I was involved in its development’). Understanding, belief and ownership are the keys to improved execution (see figure 4.9). And as others ‘down the line’ are updated, it’s from a position of first-hand knowledge and passion — the corporate strategy now has an army of internal advocates. Figure 4.9: strategic momentum Participatory strategic design mobilises the organisation’s intellectual resources, along with its energy and passion. Arie de Geus categorises corporate decisions as either routine or non-routine. Routine decisions are those for which management and employees already have the necessary knowledge and experience that allow them to respond effectively. These decisions can usually be made quickly and fairly instinctively. Non-routine decisions, on the other hand, tend to be larger in scale, often requiring major internal changes in response to external change. These decisions are far less common and far more important, as they define a company’s future direction at critical junctures. Non-routine decisions also tend to take ‘an inordinate amount of time to be implemented’, especially when treated as the domain of an exclusive club: We found that decisions taken by isolated small groups [external consultants] producing a brilliant idea always seemed to run into difficulties when it came to implementation - the rest of the company did not want to do it or did not understand it … Therefore, it seemed important that the implementers are part of the learning and decision-making process, otherwise an awful lot of time is wasted in the implementation phase.20 In other words, participatory strategy development speeds up non-routine decision-making. In his book The Living Company, de Geus describes the four typical stages of the decision-making process as perceiving, embedding, concluding and acting21: Expressed linearly against time (t0–t4), these four phases appear, with the aforementioned breakdown in implementation indicated, in figure 4.10. Figure 4.10: de Geus’s four phases of decision making Driven by a belief that the critical success factor in any decision-making process is speed measured between perceiving and action (t1 ➔ t4), de Geus helped to instigate the use of collaborative ‘play’ in decision making, allowing managers to experiment using simulation and scenarios. Not only did the rate of institutional learning accelerate (another critical success factor!), but so too did the speed of decision making. In fact, for non-routine decisions, the introduction of a collaborative approach to experiential learning through the use of scenarios improved the speed of decisions by a factor of 2. Necessary, fundamental changes to the business were now being implemented at twice their former speed22 (see figure 4.11). Figure 4.11: accelerating decision making Participatory scenario development, with its emphasis on organisational learning, can halve the time between perceiving and acting on strategic issues. Yet even this significant improvement doesn’t fully capture the benefits derived from collaborative strategy development. While de Geus emphasises the improved speed between organisational perceiving and acting (t1 ➔ t4), further improvement still lies in the initial act of perceiving (t0 ➔ t1) (see figure 4.12). Figure 4.12: earlier decision making The priming effect of scenarios improves managerial sensitivity to external change, further accelerating the decision-making process. Emerging from the scenario process with an enhanced understanding of industry dynamics and possible future outcomes, the organisation now has a framework for anticipating external changes. Such a framework enables it to perceive changes or issues of significance earlier, thereby reducing the perception gap (t0 ➔ t1). This is the priming effect of scenarios. Note: The significant benefit of increased organisational sensitivity to early signals of change is covered extensively in chapter 13.

Strategy is planning

Strategy is dour

Strategy is output

It’s time to rethink strategy

Strategic principles

1. STRATEGY AS RESOURCE

2. STRATEGY AS PROCESS

3. STRATEGY AS CREATIVITY

Reperceiving scenarios

Transformational scenarios

4. STRATEGY AS LEARNING

Acting with confidence

Slowing down change

Making the future familiar

5. STRATEGY AS PARTICIPATION

Participatory learning

Speeding up decision making