Appendix A

India? Really?

Countering Skepticism about Transferring Practices from India to Developed Countries

Over the last five years, as we have shared our research with colleagues, we have encountered skepticism about our thesis that India can offer lessons for health-care reform in the United States.

“India?” people ask. “Really?”

“Yes, India!” we reply, time and again.

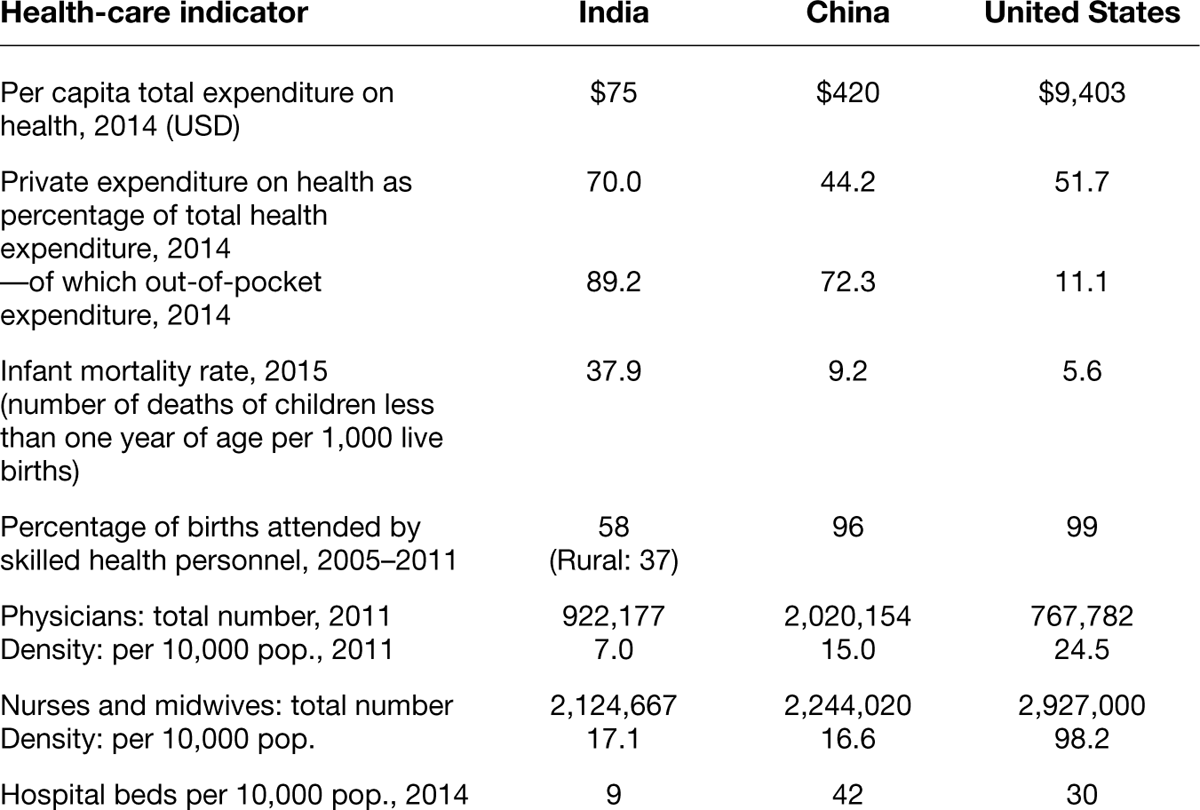

But the question is understandable. After all, India’s overall performance in the health-care sector leaves a lot to be desired, compared with the United States and even with China (see table A-1). So we would like to address some recurring doubts. Skeptics’ concerns typically fall into one of two camps: skepticism about the exemplars’ results and skepticism about reverse innovation. Let’s take them one at a time.

TABLE A-1

Health-care statistics: India, China, and the United States

Source: Compiled from World Bank and World Health Organization databases and from World Health Statistics 2017: Monitoring Health for the SDGs.

Skepticism about Results: Are Indian Exemplars Really Achieving High-Quality, Low-Cost Care for All, and Are They Really Making Money at It?

Here we address five frequently asked questions from economists, insurers, patient advocates, and hospital CFOs. To help with this discussion, table 1-2 in chapter 1 presented prices for a range of medical procedures in India and the United States. A second table in this appendix, table A-2, provides more in-depth information on the prices, quality, volume, subsidized care, and financial results of one of our exemplars, Aravind Eye Care System, in 2012–2013, when we began our research.

Aravind Eye Care System, FY 2012–2013

New York Eye and Ear Infirmary was ranked no. 11 among all eye hospitals in the United States by U.S. News & World Report in 2012 and is the highest-ranked eye hospital for which volume and financial data were publicly available.

Indian rupees (INR) were converted to US dollars (USD) at the rate of 1 USD to 50 INR, the rate prevailing in 2012–2013.

n/a = not available

Were the hospitals’ bills really that low, or were there hidden charges?

They were really that low. The prices shown in table A-2 are bundled prices—that is, they include the full price of the listed procedure, including diagnostics and follow-up care and any unanticipated tests or procedures required in a particular case. These prices were usually transparent to the patient, as they must be in India, because insurance coverage is limited and patients must pay out of pocket. Upgrades were sometimes available for nonmedical amenities such as private hospital rooms. These were typically priced separately. As you can see, the Indian exemplars didn’t just charge low prices. They charged ultra-low, comprehensive prices.

For example, Aravind’s fee for a comprehensive eye exam was only $1, which was low enough to encourage everyone to get tested (see table A-2). Its price for cataract surgery included consultations before the procedure, hospital and operating-room charges, a surgeon’s fees, medications, recovery, room and board, and postoperative consultation. For poor patients, Aravind also provided free screening, free eyeglasses, free accommodations, and free transportation from their villages if they required surgery.

Similarly, Narayana Health’s price of $2,100 for a coronary artery bypass graft included preoperative tests, surgery charges, a doctor’s fees, medicines, and postoperative recovery. This is not a subsidized price. In fact, Narayana’s cost, as opposed to price, was even lower, estimated at between $1,100 and 1,200 for each open-heart surgery.

Finally, at our maternity-hospital exemplar, LifeSpring, the price for a normal delivery was $120. That price included prenatal care (including multiple consultations with obstetricians, three ultrasounds, lab work, and an HIV test), the delivery itself, medicines, and hospital-stay charges. A cesarean delivery cost $180 more, to cover the surgery. In all cases, LifeSpring also provided one month of postnatal care, including government-sponsored vaccinations and one visit each with an obstetrician and a pediatrician. LifeSpring posted these prices prominently in its hospital lobbies so patients would know exactly how much a delivery would cost well in advance of receiving the bill.

Was the care actually high-quality, despite these ultra-low prices?

Yes, just take a look at the quality metrics in table A-3. Our hospital exemplars are exemplary for a reason. All of the physician founders of these hospitals trained to very high standards, four of them in the United States and the United Kingdom, and quality health care was their mission. Several of the hospitals were accredited by Joint Commission International (JCI) or by its Indian equivalent, the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (NABH). One hospital, Aravind, chose not to seek accreditation for fear that accreditation would stifle experimentation and curtail innovation, but as shown in tables A-2 and A-3, Aravind’s outcomes were as good as or better than those of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service. LifeSpring, the maternity hospital, was not big enough to seek accreditation.

Indian hospitals: quality-of-care indicators

n/a = not available

- Joint Commission International (JCI) is the international arm of the Joint Commission, an independent, nonprofit organization that accredits more than 15,000 health-care organizations in the United States. Its Indian equivalent is the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (NABH). Accreditation by JCI was usually limited to the group’s flagship hospitals, whereas NABH accreditation was more widespread.

- The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute provides information on cancer statistics in an effort to reduce the cancer burden among the US population. It is maintained by the National Cancer Institute belonging to the US government.

- Based on case study of Narayana Health by T. Khanna, K. Rangan, and M. Manocaran, “Narayana Hrudayalaya Heart Hospital: Cardiac Care for the Poor,” Case 505-078 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2005), p. 3. Also, Narayana Health’s patients were probably at higher risk than US patients for four reasons: 1. As the largest cardiac hospital in India (and the world), Narayana accepted patients with complications who may have been turned down by other hospitals. 2. Indians tend to have weak hearts. 3. Indians generally go for heart surgery in advanced stages of disease. 4. Poor hygienic conditions and higher pollution outside the hospitals may increase postoperative complications and mortality.

- Metrics used by American Journal of Therapeutics.

Some of the exemplar hospitals also benchmarked themselves against international standards for medical care, including rates of complications for different procedures. The data suggests that their medical outcomes were comparable to those prevailing in the West. For example, the five-year survival rates for patients with breast cancer (stages 1 through 3 combined) at HCG Oncology averaged 86.9 percent from 2003 to 2009, compared with an average rate of 89.2 percent for such patients in the United States in the same period. Deccan Hospital patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis for kidney failure showed outcomes statistically identical to those of US patients undergoing hemodialysis, the more expensive treatment commonly used in the United States.

Aravind, the eye hospital, has come under particularly close scrutiny, perhaps because of its wildly successful run of more than forty years in India. Rigorous studies by renowned ophthalmologist David F. Chang of the University of California, San Francisco, and others have shown that medical outcomes for Aravind’s revolutionary manual small-incision cataract surgery were generally comparable to those of the costlier and more sophisticated procedure known as phacoemulsification.1 In fact, in an editorial in the British Journal of Ophthalmology, Chang argued that the technique produced better outcomes than phacoemulsification in developing countries where cataracts are more advanced and severe (typically for having gone too long untreated).2 In other work with Aravind colleagues, Chang found that the streamlined sterilization methods and unconventional operating-room protocols used at Aravind did not produce higher infection rates than those associated with traditional methods and protocols, and that Aravind’s outcomes were as good as those of hospitals with smaller volumes and a slower pace of surgery.3

Did the hospitals really cater to the poor or just to the rich?

Targeting the rich is a surefire way to succeed in health care in poor countries like India. Elites, tycoons, high-ranking politicians, and expatriate managers—these people get sick and die as regularly as do the poor, and they are willing to pay handsomely for medical care. But our Indian exemplars were not concierge medical practices. As explained in chapter 1, the Indian exemplars extended care to all, often providing free or subsidized care for the poor. For instance, at LifeSpring, with its chain of maternity hospitals located in and around the city of Hyderabad, most patients were the urban poor, who paid prices that were 50 percent to 70 percent below those charged in other private Indian hospitals.

Don’t most of these Indian innovations involve pretty simple procedures and practices?

Some do, some don’t. We do profile three Indian hospitals that performed ordinarily straightforward interventions such as cataract surgery and maternity care, but the other four Indian exemplars dealt with many complex procedures involved in cardiac care, renal care, and cancer care. Moreover, these latter four hospitals used many of the same management innovations that we observed in hospitals tending to eye care and maternity care. Thus, the breakthrough business model for health-care delivery that we describe in chapters 2 and 3 has broad applicability to all medical procedures and hospital practices. And here’s something else to think about: The field of medicine keeps improving. What was complicated in the past has become more straightforward today. We believe that as time goes on, innovations pioneered in India will become relevant to a wider swath of medical procedures and management practices.

Did the Indian hospitals really make money?

Yes, they did make money, and decent amounts of it, as we explained in chapter 1. Although it was a nonprofit hospital and served the highest proportion of free or subsidized patients among the hospitals we studied, Aravind had an EBITDA margin and a net profit margin that were the highest in our sample. LV Prasad Eye Institute enjoyed similar success since its founding, covering all its operating costs as well as its training and research expenses, with money left over each year.

So, yes, it’s true. These seven Indian hospital systems have achieved what US health-care reformers have been talking about, dreaming about, and fighting about for decades: high-quality, low-cost health care for everyone, and money in the bank at the end of the day.

Skepticism about Reverse Innovation: Can US Hospitals Really Apply Indian Practices?

We noted in chapter 2 that India presented three realities that laid the groundwork for value-based competition: (1) a huge, low-income population that mostly paid for health care out of pocket, (2) a shortage of health-care resources, and (3) an unfettered industry. Conditions in the United States are exactly the opposite on each of these fronts (see the sidebar “Indian versus American Health-Care Context”): The largely middle-class population relied on third-party insurers to pick up most of its health-care costs. The country generally enjoyed a surplus of medical resources (though those resources were unevenly distributed). And health care was highly regulated.4 For many years, the United States eschewed value-based competition in favor of “regulated competition,” including the country’s fee-for-service payment system, which distorted incentives for industry players. As a result, US health care evolved in entirely different ways than Indian health care.

While Indian patients shopped around for value, US patients became indifferent to price because of third-party payment for health care, which also added administrative complexity and costs to the system. Because most hospital costs (e.g., doctors’ and nurses’ salaries, depreciation on buildings and equipment, administrative overhead, and interest expenses) were fixed, hospitals were eager to drive up volume and utilization. A built bed became a filled bed as supply drove demand. Fee-for-service reimbursement encouraged providers to perform unnecessary tests and procedures and didn’t reward better care, only more of it. The net result was that US health care became extraordinarily expensive and uneven in quality.

A doubter might still note that even if our characterization of the Indian exemplars’ results is accurate, won’t differences between the American and Indian contexts limit what can be transferred and applied to US health care? Yes, of course there will be limitations and adaptations, but what impresses us is how much can be transferred to good effect.

Let’s take a look at the five questions we’ve been asked most often about reversing the Indian innovations.

What about labor costs? Don’t they account for most of the cost savings in India?

Surprisingly, no. Nurses, paramedical staff, and administrators were certainly paid less in India than in the United States, sometimes dramatically so. Some earned only 2 percent to 5 percent of what such workers in a US hospital would earn. But medical specialists, who accounted for more than half the salary bill in a typical Indian hospital, were a different story. Many Indian doctors trained and practiced in the United States or the United Kingdom before returning to work in India. They were highly skilled and financially savvy. They knew their worth on the global market. Cardiothoracic surgeons, nephrologists, ophthalmologists, and oncologists in India typically earned anywhere from 20 percent to 74 percent of what their American counterparts did.5 For example, Aravind’s ophthalmologists earned $50,000 annually compared with the $253,000 that was the average for US ophthalmologists, and Narayana’s senior cardiothoracic surgeons grossed between $150,000 and $300,000, compared with $408,000, the median income for their US counterparts.

We calculated what the cost of an open-heart surgery at Narayana Health would have to be if the salaries of its doctors and other staff were adjusted to match US levels. Even with commensurate wages factored in, and no reduction in headcount to match lower US staffing levels, Narayana’s cost for open-heart surgery would still be only 3 percent to 12 percent that of a comparable procedure in a US hospital (see table A-4). The labor-cost differential just isn’t that important.

TABLE A-4

Open-heart surgery at Narayana Health: salaries are only part of the equation

Moreover, our Indian hospitals faced cost drivers that American hospitals didn’t. For example, imported devices such as stents, valves, and orthopedic implants, as well as high-end equipment such as CT scanners, PET-CT scanners, MRI machines, and cyclotrons were subject to transportation costs and import duties. The cost of capital in India could be as high as 14 percent per annum, more than double that in the United States. And the cost of land in urban areas such as Bangalore and Hyderabad was very high—two-thirds that in Manhattan. As a result, Narayana’s 21-point labor-cost advantage relative to Cleveland Clinic, for example, was mostly offset by a 17-point disadvantage in its cost of supplies, pharmaceuticals, and other direct expenses (see table A-5). Overall, the result was a win-some, lose-some cost structure for Indian hospitals compared with that of hospitals in the United States.

TABLE A-5

Cost structure of Cleveland Clinic versus Narayana Health

Notes: Cleveland Clinic categories as reported in its 2012 Annual Report. Narayana Health data matched to Cleveland Clinic categories to the extent possible. Supplies included stents, valves, etc. Pharmaceuticals included medicines, reagents, blood from blood banks, etc. Other services included radiology, power and fuel, linen/laundry, food catering, bad debt, and clinical research. Administrative costs included repairs and maintenance, housekeeping, waste disposal, traveling and conveyance, telephone, printing and stationery, rent, security, insurance, business promotion, rates and taxes, and other costs, including unspecified amortization.

Narayana Health’s sales and assets, in Indian rupees (INR), converted to US dollars (USD) at a rate of 1 USD to 50 INR, the rate prevailing in 2012.

What about volume? How can the United States ever achieve India’s economies of scale?

True, India has four times the population of the United States, and Indian hospitals do enjoy cost advantages based on economies of scale. But consider three things. First, population and health-care markets can vary independently. US volumes may be lower than India’s in some areas (e.g., eye care) but higher than India’s in many other areas (e.g., heart disease, kidney problems, obesity-related problems, and Alzheimer’s). Second, even for medical procedures for which US volumes are lower in the national aggregate, individual hospital chains or specialty hospitals might attract sufficiently high volumes to see similar economies of scale. Finally, many of our Indian exemplars achieve cost advantages in ways unrelated to volume. For this reason, countries much smaller than the United States—e.g., Finland and Sweden—have adopted Indian-style innovations with significant gains.

But aren’t these Indian hospitals spared the overhead costs of running educational and research programs?

No. The higher cost position of major US hospitals cannot be explained by the fact that they often have twin missions: both treatment and research and training. Five of the seven Indian hospitals we profiled also engaged in applied research and knowledge building through clinical innovations, and they functioned as teaching hospitals that invested heavily in training medical staff. In fact, they graduated more medical professionals than most hospitals in India. Aravind Eye Care alone was estimated to have trained one in six ophthalmologists working in India, for example, while also training thousands of young women to serve in the newly created occupation of midlevel ophthalmic paramedic in its own hospitals and clinics across India.

The Indian hospitals also allocated resources to develop and perfect clinical innovations as doctors adapted procedures to rein in costs and deal with local problems. For example, the vast majority of coronary-bypass procedures at Care Hospitals and Narayana Health employed an unconventional “beating-heart” approach, as described in chapter 3. Given the shortage of cornea donors, LV Prasad Eye Institute developed a novel method of corneal slicing that allowed a single cornea to be used to treat two patients. Similarly, Aravind mastered manual small-incision cataract surgery, which was faster to perform and required less-sophisticated equipment than standard Western practices. In the same way, HCG Oncology perfected novel procedures for treating breast, neck, and throat cancers. All of these incubator and dissemination efforts involved overhead expenses similar to those at teaching hospitals in the United States.

But isn’t regulation killing innovation in the United States? Indian hospitals don’t face that problem!

It is true that Indian health care is less regulated than US health care. In fact, the Indian regulatory environment is pretty lax, although this was starting to change slowly in 2017. India also has far fewer malpractice suits, and hospitals are less pressured by unions and insurance interests. These pressures on the US health-care system certainly inhibit its efficiency and its ability to innovate. But by the same token, India is likely to be a better laboratory for health-care-delivery innovations than the United States. Not all Indian innovations will reverse easily, and some likely cannot be reversed at all. But many can be transferred directly, or with adaptations, and some will show such promise that they will invite disruption of the burdensome US system.

Unless there is a system-level change, how can US hospitals really benefit from Indian-style innovations? Can bottom-up change really work?

Absolutely. We have seen it, and we describe several Indian-style innovations under way in the United States in part two of this book. No doubt, there is a system-level problem in the United States, and one of the symptoms is inertia. But systems do change. Over time, US regulations can and will change so that innovations to lower cost, expand coverage, and improve quality will become easier to adopt. Both the market and the public good demand it. We hope this book will catalyze bottom-up changes that will encourage top-down policy reforms, so that the two will be mutually reinforcing.

So, here’s the bottom line: while the Indian exemplars, vis-à-vis US hospitals, did enjoy labor-cost advantages and a lighter regulatory burden, other costs were actually higher in India and other pressures were similarly burdensome. It would be a mistake to dismiss the Indian experience as irrelevant for rich countries, just as it would have been a mistake in the 1960s to dismiss the experience of Japanese manufacturers such as Toyota.