CHAPTER 11

Integrating Assessment Results and Executive Coaching: Development

There is nowhere to hide. Not even the executive suite is safe from the changes sweeping business today. In fact, the impact of those changes is felt most keenly at the executive level. CEOs, COOs, CFOs, and senior VPs—like everyone else—have to hit the ground running and keep running fast. Stockholders and stakeholders demand quick results. Teams must work more efficiently under greater pressure. High-potentials and emerging leaders need to be identified and developed earlier and more effectively. Business savvy—always important—has been taken to new heights. Add to this the quest for job satisfaction and life balance, and you have the dynamic tension that creates the vital need for executive coaching.

Executive coaching is a professional process that links individual effectiveness to organizational performance. It is a strategic process that helps organizations attract and retain great leaders, enables executive teams to improve leadership and team performance, and supports senior executives responsible for making crucial business decisions and achieving outcomes. It truly provides the shock absorbers on the often bumpy road to organizational change.

The powerful advantages in the leadership development process, particularly in areas where performance goals are at risk, has moved coaching to top-of-mind for executives and HR leaders alike. Yet there is still a tremendous gap between what is expected of executives and the available resources to help them acquire both the inner core attributes and outer core skills and competencies required to achieve those expectations. Executive coaching can close that gap. The reality, however, is that while executive coaching is top-of-mind for executives and HR, only 35 percent of the organizations we surveyed in our Trends in Executive Development Research Study (Pearson, 2011) utilize executive coaching as part of their high-potential developmental programs. By comparison, 48 percent of the organizations utilize executive coaching for their VP-level and above executives. For high-potentials, organizations continue to emphasize developmental job assignments (70 percent) and custom training programs (51 percent) as their primary developmental strategies. We were surprised to learn that 65 percent of the organizations surveyed do not cite executive coaching as an important developmental strategy for their high-potential and emerging leader talent pools. I see this as a significant issue and opportunity for organizations, especially in light of what different generations expect from their employers. (For example, Generation Xers want a casual, independent, flexible environment and a place to learn; Generation Yers want a structured, supportive, and interactive environment.) More than anything else, it is critical to understand that both generations make up nearly 100 percent of any organization’s future leader pool and that both generations crave continuous growth and connectedness with people.

Executive coaching represents a powerful strategy for meeting the continuous growth and connectedness needs of your future leaders. That said, there is a lot of variability in the world of executive coaching. Like anything else, there are excellent coaches, and there are horrendous coaches. It is important to never underestimate the importance of hiring external coaches who have a solid operations mindset, who have operations experience, and who have actually been on the firing line. Building trust and empathy with high-potential coaches is everything, and I have found that having operations experience goes a long way in helping a coach build rapport, trust, and credibility with coachees. It is also important to understand the philosophy of the coaches you are considering partnering with. They should be able to verbalize their philosophy concretely, without hesitation. For example, here’s my philosophy, which comes from my website:

John’s powerful coaching approach blends in-depth diagnostic assessments that identify a leader’s “inner-core” values, character, beliefs, emotional makeup and behavioral tendencies (both mature and derailer traits) with “outer-core” assessments such as 360-Degree surveys and leadership interviews which reveal how effectively the executive executes the “outer-core” skills and competencies required for success. John works closely with the executive coachee and sponsoring team to create an individual development plan that leverages the coachee’s enduring strengths and addresses their development needs with a passionate focus on achieving measurable behavioral change and improvement.

The remainder of this chapter details how I go about my coaching work with senior executives and high-potentials. You will notice I am a believer in leveraging the coachee’s stakeholders and mentors throughout the coaching process. The strength and success of any coaching intervention is in direct proportion to how well the coach has created and facilitated a coaching process whereby the coachee actually learns more from their stakeholder and mentor interactions than the coach. The goal of any great coach is to create for their coachees a foundation for continuous self-discovery and learning that endures well after the conclusion of the coaching assignment. If you are considering partnering with an executive coach and the candidate states directly (or indirectly) that he or she is the most important variable in the development equation, I can say unequivocally that you have the wrong coach.

Typical Executive Coaching Applications

Executive coaching takes a number of forms:

• Competitive advantage consulting and coaching helps executives enhance their leadership skills to stay ahead of the curve and drive business results and financial results.

• Stretch assignment coaching creates a safety net for executives who are in critical assignments with intense time, budget, and outcome expectations.

• High-potential coaching supports executives who are identified as leaders positioned for growth and success in the organization.

• Coaching for performance provides focus, support, and strategic business knowledge to executives whose units are behind plan and at risk of failure.

• Leadership development coaching strengthens a leader’s inner core attributes and outer core skills and competencies in support of organizational goals and individual leadership success.

• Team coaching helps teams rapidly assimilate new skills and behaviors.

Regardless of the application, effective coaching follows a defined, consistent, multistage process that always promotes self-awareness, the will to change, and the execution of attributes and competencies that drive individual and organizational performance to new heights. The application of coaching, though consistent, is also customized to meet the individual needs of each coachee and the business goals of the organization.

Coaching Examples from the Archives of JohnMattonePartners, Inc.

Competitive Advantage Consulting and Coaching

An international company has a goal of increasing market share in the United States by a certain percentage in two years. To support this goal, the senior executive team wanted to corroborate that the required competencies to meet this goal were (1) the ones they had already isolated as being critical and (2) those actually possessed by the senior leaders who were responsible for achieving this goal. JohnMattoneParners (JMP) implemented its Stealth Competency Mapping Process (SCMP) to verify that they had, in fact, isolated the critical competencies. In addition, through the use of 360 interviews, executive interviews, and the use of the Hogan assessments, each leader met with JMP coaches to create individualized plans to improve performance against these goals.

Stretch Assignment Coaching

An executive was appointed the new CEO after the unexpected resignation of his predecessor following a stormy board meeting. The board gave the new CEO a challenge: Turn this company around in six months. A hiring and budget freeze was imposed by the parent company. The new CEO must get the immediate acceptance of his leadership from senior executives and quickly communicate a clear vision to the rest of the company. The previous CEO was well liked. The new CEO is reserved, but fair and objective. The new CEO asked JMP for help because he knew he may not get the objective feedback or advice early on that is required.

High-Potential Coaching

After reviewing its succession plan, a large transportation company identified two potential replacements for the VP of customer service role. Both executives met with JMP to establish goals and review the four-step process. JMP met with each executive’s stakeholders—current VP, peers, employees, and a couple of key client accounts—to collect feedback about their behavioral style, skills, and competencies. In addition, each executive was assessed using the CPI-260, FIRO-B, Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Assessment, and the MLEI. The results were presented to each coachee, and from there action plans were created to sustain their effective behaviors but improve the areas required for the new role.

After months of coaching and development, each executive’s stakeholders were asked to complete a minisurvey to determine whether they had improved. Results were tabulated, and an additional coaching meeting was conducted to review results and set another action plan. In both cases, the executives had improved in the areas identified as being critical to their success. One executive eventually was selected for this VP role; however, the other executive was selected for another VP role based on the growth and development from this experience.

Developing Leadership Skills

An executive was identified for promotion and has many of the competencies required for success except she is seen as introverted and shy, which will not play well in this role. Under stress, she becomes arrogant and aggressive, which also will not play well in this role. She is, nevertheless, a marketing genius and incredibly creative; these are the assets the organization needs in this visible role. This leader has never been coached and has received very little feedback in her career about how she comes across. JMP employed both 360-degree and objective assessments and engaged in a series of coaching sessions over the next six months. This executive began to show marked changes. She started to open up and was more expressive and outgoing, which had a dramatic impact on her team. As she connected her new behavior with improved results, she became a very strong leader and within a year had secured the promotion.

Defining the Scope of a Coaching Intervention

The scope of a coaching intervention is based on four stages:

1. Awareness

2. Analysis

3. Action

4. Achievement

Awareness

Typically the executive coach meets with the client team, which includes the executive to be coached (client), the sponsoring executive (e.g., CEO or other senior executive), the VP of Human Resources, and the client’s direct manager. The purpose of the meeting is to:

• Discuss the situation and its background and identify the goals, objectives, and expected outcomes of the proposed coaching intervention.

• Clarify management’s commitment to the client and the coaching process being offered.

• Provide an overview of the coaching process, timetable, and parameters of the engagement.

• Identify key stakeholders (five to seven)—boss, peers, and direct reports—who can be interviewed to obtain feedback on the client’s skills and competencies. This step is often supplemented with a 360-degree survey delivered to a larger audience. If this survey step is implemented, the client team should identify respondents who are in the best position to offer objective feedback.

The executive coach meets with the client to:

• Reinforce the information discussed in the group meeting and clarify expectations as necessary.

• Develop more awareness of the situation and the commitment of the client to become the absolute best leader he or she can be.

• Conduct an in-depth interview, including life and career history, self-perceived behavioral and leadership strengths and development areas, and motivation to sustain strengths and improve developmental areas.

A typical in-depth interview protocol entails the following questions:

• Goals for the coaching relationship?

• What does a great coaching session look like to you?

• What are you most looking for in our time together?

• Do you like sessions to be more structured or less so?

• Do you prefer a fast, moderate, or slow pace?

• What else would you like me to know about you as we work together?

• If you knew you could not fail, what would you do professionally?

• What advice or theme do you live by?

• Please write a short paragraph about yourself that could be used to introduce you.

• Please write a paragraph about yourself fast-forwarded 5 years from now.

• What do you do to achieve balance mentally, physically, emotionally?

• What makes you feel stuck?

• What makes you feel successful?

• What is your self-talk about your life as a whole?

• Describe your current role?

• What other roles have you held in this or previous organizations?

• What are the biggest challenges you face in your current leadership role?

• What are your two strongest leadership strengths?

• What are your two leadership areas most in need of development?

• What is your greatest professional accomplishment? Why?

Analysis

Phase I: Assessments Launched

• Stakeholder interviews are conducted and/or 360-survey is launched.

• Client is administered any number of online, inner core assessments, such as the Hogan Suite, CPI-260, FIRO-B, Myers-Briggs, Mattone Leadership Enneagram Inventory, Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking, etc.

Phase II: Feedback Session and Planning Model Introduced

• A client/coach meeting is scheduled to (1) set expectations for the analysis meeting; (2) set expectations for the remainder of the coaching meetings; (3) review target competencies required for success; and (4) review and debrief 360 assessment, interviews, and objective assessment data.

• As part of this meeting, the client and coach transition to reviewing the Assessment Driven Individual Development Planning (IDP) Model, and Matrices.

• Typically, over the course of one to two phone meetings, the client and coach finalize the IDP. Once finalized, the IDP is shared with the client’s manager, sponsor, and HR for agreement and support of the IDP and timetable.

Action

This phase is focused on taking specific actions to sustain strengths and develop the leadership skills identified in the IDP. These actions may include:

• Trying out new behaviors and reporting back to the coach.

• Building new skills while refining others.

• Developing key relationships in the organization.

• Interviewing successful executives who have reference reservoirs the client may not yet possess.

• Reading assignments and reporting back what they have learned.

• Meeting with stakeholders to get their input on development goals and plans.

• Attending outside training programs.

• Making an important presentation to a key executive in the organization.

During this phase, the client and coach communicate regularly, either in person or on the phone, in order to discuss specific situations and maintain focus on the details of the plan.

Achievement

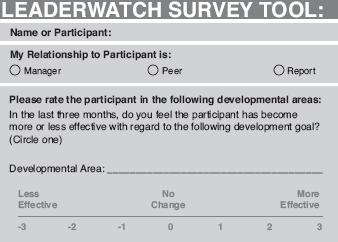

• Typically, LeaderWatch Abbreviated Surveys are sent to stakeholders to obtain feedback on the client’s improvement and progress.

• These results are debriefed with the client, and course correction is suggested if necessary.

• Once the client and sponsors have agreed that the coaching process has achieved the desired results, the coach begins a less intensive phase-down approach.

• A final, formal follow-up session can be conducted one to three months after the final coaching session to obtain feedback on achievements, celebrate accomplishments, and present the final report on the success of the coaching assignment.

Analysis/PHASE II Feedback Session and Planning Model: Suggested Flow of Meeting

• Introduce the Stealth Fighter (refer to Chapter 1).

• Explain the importance of increasing leader Capability, Commitment, and Alignment—under the umbrella of the leader’s increasing capability—creating an environment in which the leader’s direct reports become more capable, committed, and aligned.

• Introduce the concept that prescription before diagnosis is malpractice.

• The Stealth Fighter is critically important; however, the competencies required for success are even more critical. The Stealth needs a target (see Chapter 2).

• The purpose is not to assess the leader just to assess; assessment and solid diagnostic data will help the leader fly the Stealth Fighter toward the defined target.

• Provide a road map of what to expect in the session:

![]() Focus on understanding the target.

Focus on understanding the target.

![]() Analyze assessment results against the target.

Analyze assessment results against the target.

![]() Share the Wheel of Success (see Chapters 3 and 4), which identifies both the inner and outer core elements that drive success as a leader. (Hopefully, the stakeholder interviews and the 360 are aligned with the Wheel of Success.)

Share the Wheel of Success (see Chapters 3 and 4), which identifies both the inner and outer core elements that drive success as a leader. (Hopefully, the stakeholder interviews and the 360 are aligned with the Wheel of Success.)

![]() Emphasis should be placed on describing the predictive relationships that exist between the leader’s inner core, predominant behaviors, and the leader’s execution of skills and competencies that drive success.

Emphasis should be placed on describing the predictive relationships that exist between the leader’s inner core, predominant behaviors, and the leader’s execution of skills and competencies that drive success.

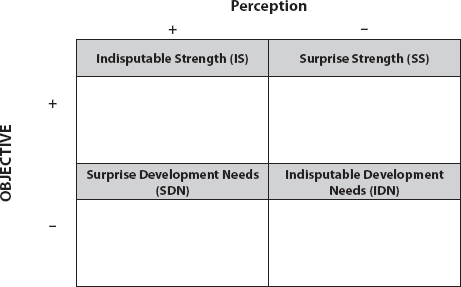

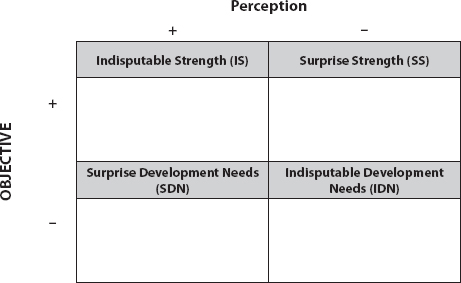

![]() First goal: After reviewing assessment data, partner to identify (a) indisputable strengths, (b) surprise strengths, (c) indisputable development needs, and (d) surprise development needs.

First goal: After reviewing assessment data, partner to identify (a) indisputable strengths, (b) surprise strengths, (c) indisputable development needs, and (d) surprise development needs.

![]() Second goal: Ensure that the goals established and action plans identified are to be tied to the Wheel of Success.

Second goal: Ensure that the goals established and action plans identified are to be tied to the Wheel of Success.

![]() Share schedule of coaching calls (e.g., one-hour session every two weeks for six months).

Share schedule of coaching calls (e.g., one-hour session every two weeks for six months).

![]() Share a typical call (i.e., review progress, new issues, and concerns, etc.)

Share a typical call (i.e., review progress, new issues, and concerns, etc.)

• Leader improvement and ROI are based on stakeholder involvement: sharing goals and action plans; getting feedback; thanking them for their feedback and guidance; etc.)

• Coach/leader partnership

![]() Stealth Fighter

Stealth Fighter

![]() Objective calibration versus Stealth Fighter

Objective calibration versus Stealth Fighter

![]() Accountability

Accountability

![]() Diligence and focus

Diligence and focus

![]() Brainstorming

Brainstorming

![]() Setting goals

Setting goals

![]() Setting action plans

Setting action plans

![]() Challenging each other

Challenging each other

![]() Accept there will be ups and downs

Accept there will be ups and downs

• Review stakeholder interview results (confidentiality) and 360 results

• Review objective assessment results

Share Assessment Driven Individual Development Planning Model, and Matrices (discussed later in this chapter).

How to Deliver 360-Degree Results

The most effective way for presenting feedback in a nonoverwhelming manner involves clustering feedback from different parts of the assessment into larger themes. Those themes span different tactical skills and competencies. It is important to do this in a balanced manner for both strengths and development opportunities. Here is a good way to get started:

• Examine open-ended feedback. In this section, raters have the opportunity to express themselves, and any themes in this section will most likely be supported by one or more behavioral indicator ratings in the report.

• Examine highly and lowly ranked behaviors. Do they cluster under certain skills or competencies?

• Go to the highest- and lowest-ranked competencies/skills in the report. Are all raters responding in a similar way, or do different rater groups perceive different strengths and development needs?

• Think about how you would summarize each strength/opportunity cluster in a nonthreatening way that is supported by different behaviors in the report. You can also refer to different examples if those were provided in the open-ended section.

• Check for variance in response patterns, such as (1) between self and others, (2) within rater groups, (3) between rater groups, (4) comparison to group and/or 360 instrument norms, (5) perception gaps (between self and other) by each rater group.

Examining Open-Ended Feedback Themes

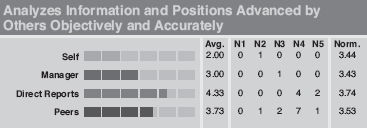

In most 360 instruments, there is an open-ended section in which raters can express their opinions and perceptions. When given an opportunity to provide open-ended feedback, raters express what comes to mind first in regard to strengths and development needs. To best prepare for your debrief and coaching session, study the open-ended feedback to identify themes that emerge (see Exhibit 11.1).

Exhibit 11.1: Open-Ended Feedback Form

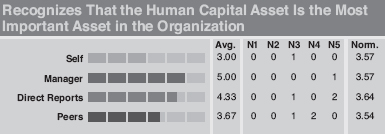

Response Pattern Variability

The response patterns of different rater groups give you information about how the coachee is perceived by different rater groups. With this information, you can now examine individual items where responses differ from what you would typically expect. In the example in Exhibit 11.2, the manager is providing nearly the highest score possible. However, let’s say that throughout the report, the manager has provided consistently lower scores than either the direct report or peer group. For this particular behavior, “recognizes that the human capital asset is the most important asset in the organization,” however, the manager is seeing something very different and in this case very positive. With this information, you now have a good sense for what that manager appreciates and emphasizes.

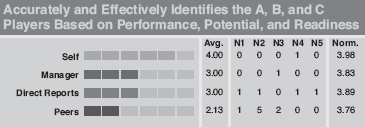

Intragroup Item Variability Analysis

Item frequency distributions (i.e., how many raters provided what score) can give you an insight into how evenly or unevenly a perception is distributed. You should be looking for:

• Items where almost all raters provided higher scores and no one provided a low score; those would be “indisputable strengths.”

• Items where raters are expressing concern.

Although in most cases it is expected that the coachee could receive lower scores from some raters, special attention should be paid to the context of the competency and specific behavior. For example, just one low rating in a behavior that is critical (see Exhibit 11.3) could be enough to warrant further follow-up. In this example, one peer provides the lowest rating while five provide the next lowest rating. This should be further examined and explored to see the exact behaviors that are driving these perceptions.

Exhibit 11.2: Rating Form

Intergroup Item Variability Analysis

It is also helpful to examine how similarly or differently the various rater groups respond to a specific item, in a way that may also magnify differences in the expected response pattern. In the example in Exhibit 11.4, the response provided by the coachee and the manager is substantially lower than the response provided by the direct reports.

Norm-Based Variability Analysis

If group and/or instrument norms are available, they can provide strong insight into how the strengths and development needs evidenced by your coachee compare to those of the larger population. The ability to compare your coachee’s results to norms help you understand:

Exhibit 11.3: Rating Form

Exhibit 11.4: Rating Form

• The degree to which the coachee evidences the leadership behaviors and competencies that are associated with strong leadership performance (i.e., based on aggregate/norm-based results).

• The particular strengths or development needs that should receive more attention.

The Importance of Feedback

• Feedback allows leaders to know how they are doing.

• Leaders can feel isolated; much of their agenda is confidential, so they can discuss their work with few people.

• Coaching from their boss may be in short supply, other than formal performance reviews.

• Direct reports may be too mindful of the power relationship with their manager to give open and honest feedback.

• Promotion to a more senior role often means that the challenges increase while support falls away.

• When you meet with your coachee, before looking at the data, make sure you have had the opportunity to review your interview data (see earlier section on Awareness).

Dealing with Resistance

Leaders might resist or reject feedback. Typical responses include:

• “I used to be that way, but I have changed.”

• “This was a bad time to ask for feedback.”

• “My strengths are right, but my weaknesses are wrong.”

• “My raters clearly did not understand the questions.”

• “Those people don’t really know me well.”

Remember to ask a lot of questions:

• “How do you want to use the data?”

• “What is happening in your present situation?”

• “Were you surprised by any of your feedback?”

• “What positive themes do you see?”

• “What development opportunities do you see?”

• “What changes do you want to explore making?”

Common mistakes made by leaders when receiving 360 feedback:

• Resisting or explaining away the results

• Looking only at numbers as opposed to themes

• Focusing on the boss’s ratings

• Discounting the results by attributing them to personality issues

Three common situations are as follows:

• You hear, “It isn’t me—it’s the culture here.” Your response is, “What could you do as a leader to help change it?”

• You hear, “None of this is new to me—I’ve heard it before.” Your response is, “Well, why isn’t this news?” (You might learn that the coaches are working on this area, or you might find they don’t know how to start improving. Your exploration of this will bring you in different directions.)

• You hear, “This is who I am.” Your response is, “Are you getting the success you want?”

Suggestions for Giving Feedback

• Remind the coachee that good feedback is simply information. It is not an assessment of the leader’s worth as an individual.

• Emphasize that the coachee always reserves an important choice: to accept or reject the feedback given. However, by rejecting the feedback, the coachee also rejects the choice that goes with behaving differently, which may yield the desired results.

• Acknowledge that there are many potential sources of distortion in the data but that does not invalidate the data.

• If your coachee becomes extremely defensive, you might say something like, “This process was meant to be positive and helpful. It seems to me that you are not seeing this as helpful. How would you like to proceed?”

• Always keep your cool as a coach.

• Remind your coachee of the Stealth Fighter. It’s all about increasing Capability, Commitment, and Alignment.

Best Practices in Dealing with Multirater Feedback

Don’t be afraid to seek out your coachee’s raters, especially if disparities exist in the 360 assessment results. (Hopefully, you will have agreed to this with the coachee, sponsoring executive, and the coachee’s manager at the outset of the coaching assignment. Regardless, please get permission.) When you do follow-up, ask feedback providers to prioritize the strengths and development needs of your coachee.

• Never turn your notes over to the coachee.

• Have your coachee summarize the discussion at various points to validate that they are capturing the essence of the feedback.

• Ask your coachee to isolate the positive and negative themes.

Transitioning to Individual Development Planning

Once you have worked through the assessment results (assuming you have reviewed both objective assessments and 360 results), it is time to aggregate the data in order to identify:

1. Indisputable strengths.

2. Surprise strengths.

3. Indisputable development needs.

4. Surprise development needs.

These predominant themes form the foundation for setting goals and identifying action steps, required resources, and likely obstacles.

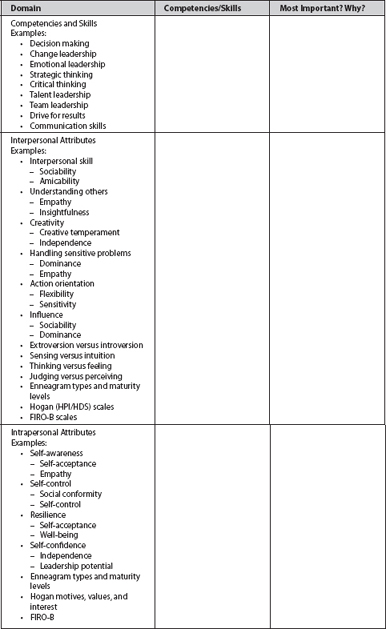

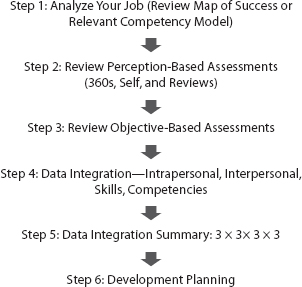

In the next few pages, you will read about a powerful tool we call the Assessment-Driven Individual Development Planning Model, and Matrices (Exhibit 11.5), which you should review with your coachee in this meeting. Over the next two weeks, you should have your coachee take the lead in completing steps 1 through 5 (see Exhibit 11.6), while staying in contact with you for guidance and feedback as they progress through the exercise. Step 6, the final step, should be done in concert either on the phone or ideally in person, where you and your coachee can identify the specifics of the plan (more on this later).

Exhibit 11.5a: The Assessment-Driven Individual Development Planning Model and Matrices

One additional note to consider regarding the Assessment Driven Individual Development Planning Model, and Matrices is that this tool can be used outside the executive coaching process by incumbent managers working in partnership with their own manager to identify and agree upon targeted strengths and development opportunities as part of the normal performance review cycle. If, in fact, objective assessments have been utilized to generate more granular and targeted information. This becomes a powerful way for incumbent managers and their own managers to work through the assessment results looking for both confirming and discrepant information. In situations where there are no objective results to consider, this tool can still provide structure and accuracy to the IDP process. Here are the suggested steps, which often are supported by internal/external coaches:

1. Assessment(s) are completed.

2. Reports are delivered to the incumbent manager and the incumbent’s manager.

Exhibit 11.6: The Six-Step Individual Development Plan (IDP) Process

3. The incumbent manager and manager separately complete the Assessment Driven Individual Development Planning Model, and Matrices, utilizing the most recent performance review information and objective assessment results (if applicable)—steps 1 through 5.

4. The incumbent and manager meet to discuss and work through their own versions of steps 1 through 5. They work together to finalize the Individual Development Plan (IDP) (step 6).

Step 1: Analyze the Job

The starting point in building an Individual Development Plan (IDP) is to identify the critical strategic competencies, tactical skills, interpersonal skills, and intrapersonal attributes required for success in your coachee’s role as a leader (refer to Exhibit 11.5a). Have your coachee review the Map of Success and/or other leadership competency models and spend a few minutes thinking about his or her role and the critical factors that determine success in the role.

Coachees should write down the strategic competencies (e.g., critical thinking), tactical leadership skills (e.g., talent leadership), interpersonal skills (e.g., extroversion), and intrapersonal skills (e.g., self-awareness) required for leader success. Once they are listed, ask the coachee to describe in his or her own words what they think is the absolute most important requirement for each area.

Step 2: Review Perception-Based Assessments

Multirater assessment data are critically important to understanding what coachees do and how they do it on the job. If you have multirater feedback such as 360 assessment results, you can use this section to summarize the results (refer to Exhibit 11.5b). With 360 data, you should put more weight on how others (i.e., your coachee’s manager, peers, and direct reports) perceive your coachee as opposed to your coachee’s self-ratings. However, in the absence of 360 results, you should use your coachee’s most recent performance review results, again placing more weight on the manager’s perception of the coachee’s strengths/development opportunities. Have your coachee review their multirater and/or performance review information and think about what the results reveal about the strengths and opportunities for development in each area. Have the coachee note the strengths and opportunities in the space provided and write down the specific multirater item or statement that was most important in leading them to that conclusion.

Step 3: Review Objective-Based Assessments

Objective-based assessments that measure a person’s inner core attributes, such as their self-concept, values, beliefs, predominant thinking, emotional patterns, and behavioral interpersonal tendencies, are all designed to help people understand why they do what they do. People’s inner core attributes (i.e., intrapersonal) are at the foundation of being able to predict how they behave and the skills and competencies they execute. Inner core attributes are typically enduring in that they have been developed, shaped, and reinforced, making them also challenging to change (refer to Exhibit 11.5c). Some objective assessments, such as skill-based simulations (e.g., TalentSim), don’t measure inner core attributes, but they do measure an individual’s performance potential to be able to execute the required skills and competencies that are associated with success in a leadership role. Assessments such as the Hogan Personality Inventory, the Myers-Briggs, the FIRO-B, the CPI-260, and others measure the critical intrapersonal and interpersonal attributes (and sometimes leadership competencies) that drive success as a leader. The Watson-Glaser II is an example of an inner core assessment that measures critical thinking patterns.

Exhibit 11.5b: The Assessment-Driven Individual Development Planning Model and Matrices

| Domain | Strengths/Opportunities | Multirater Items/ Examples |

| Strategic Competencies and Tactical Skills | Strengths: Opportunities: |

|

| Interpersonal Attributes | Strengths: Opportunities: |

|

| Intrapersonal Attributes | Strengths: Opportunities: |

Review the findings of the assessments you gave to your coachee with the coachee. Have your coachee record the strengths and opportunities for development in each area.

Exhibit 11.5c: The Assessment-Driven Individual Development Planning Model and Matrices

| Domain | Strengths | Opportunities |

| Strategic Competencies and Tactical Skills | ||

| Interpersonal Attributes | ||

| Intrapersonal Attributes |

Step 4: Data Integration—Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Skills/ Competencies

It is now important to compare and contrast your coachee’s objective assessment results with whatever perception-based assessments you have utilized across all three areas of defined leadership success: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and tactical/strategic competencies. It is important to note that most 360 assessments are not focused on measuring intrapersonal attributes; sometimes, however, raters are asked to evaluate behaviors that reflect inner core attributes such as self-awareness or self-image. Such attributes cannot be observed directly by others but can be inferred based on the behaviors exhibited. Have your coachee complete the matrix. The coachee can use his or her own self-perceptions to define the horizontal axis of the matrix. It is more appropriate to utilize 360 assessment and/or your coachee’s performance review feedback results to complete the horizontal axis of the matrices for the Interpersonal Attributes and Skills/Competencies.

Each matrix combines two axes: Objective Assessment Results (vertical) and Perception Assessment Results (horizontal). The result is four distinct quadrants (see Exhibits 11.7-11.9):

• Indisputable Strengths (IS): Objective assessment results reveal strengths that confirm perceptions (++).

• Surprise Strengths (SS): Objective assessment results reveal strengths that are discrepant with perceptions (+−).

• Indisputable Development Opportunities (IDO): Objective assessment results reveal development opportunities that confirm perceptions (− −).

• Surprise Development Opportunities (SDO): Objective assessment results reveal development opportunities that are discrepant with perceptions (−+).

Step 5: Data Integration (3 × 3 × 3 × 3)

In the following three matrices, have your coachee carry over the two strengths and development opportunities that he or she believes are the most important to the success. If necessary, go back and have your coachee review their work at step 1 to align what is important with what is required for success in the role. After identifying two for each quadrant, have the coachee eliminate one from each quadrant. That will leave one strength or development opportunity per quadrant, and the summary matrix will contain no more than 3 per quadrant—hence the 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 (see Exhibit 11.10).

Exhibit 11.7: Interpersonal Matrix

Exhibit 11.8: Interpersonal Matrix

Exhibit 11.9: Skills/Competencies Matrix

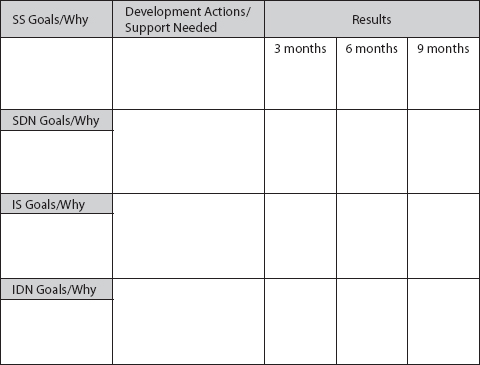

Step 6: Individual Development Plan

Step 6 is the actual creation of the coachee’s Individual Development Plan (IDP) (Exhibit 11.11). This step ensures that your coachees’ insights about their strengths and development needs (with your help) are leveraged in support of becoming the best leaders they can be and helping the organization achieve its goals.

• Work with your coachee to identify one or two development goals for each category: (1) surprise strengths, (2) surprise development needs, (3) indisputable strengths, and (4) indisputable development needs.

• Assist your coachee to be as specific as possible in writing the goals. For example, “Improve my ability to negotiate roles and responsibilities in the newly acquired sales organization” is more useful than “Improve my negotiation skills.”

Exhibit 11.10: Summary Matrix

Exhibit 11.11: Individual Development Plan

• Your coachee should also write down why the identified goals are important. This helps build commitment to the goals.

• In the second column, your coachee should write down the action(s) to take in order to achieve each goal. Emphasis should be placed on (1) what the coachee will do now to either sustain identified strengths or commit to making a change and (2) identifying other development activities that need to be pursued, such as reading assignments, interviewing other executives, projects to attempt, courses to take, and the like.

• Your coachee should also identify what support is needed from others in order to execute the change, in terms of resources, time, among other things. Having a coach whom he or she can trust and respect may be the single most important factor in achieving these development goals. As a result, you must support your coachee with regular check-in meetings and feedback.

• Finally, ask your coachee to think about the obstacles they will encounter in reaching their goals and what they can do to overcome them.

Nine-Box Placement and Executive Coaching

The Nine-Box Performance and Potential Matrix is a well-known and useful model that has been used for the past 20 years by HR leaders and line managers to help determine a leader’s or emerging leader’s value to the organization, as defined by their current performance and future potential. A simplified version of the Nine-Box appears in Exhibit 11.12. The numbers 1 through 9 are assigned to each box, where typically 1 corresponds to individuals who are seen to be the best in terms of current performance and who also offer the most promising potential.

The Nine-Box model has been used most often as part of an organization’s succession planning process. Typically, the focus has been on those classified as 1s, 2s, or 3s. These individuals typically receive the most detailed development and succession plans. People assigned to boxes 4 through 8 have historically been neglected. Given limited resources and time, this may make sense. Yet all the individuals, regardless of the boxes to which they are assigned, are still employed by the organization and are at least contributing something in their role (except the 9s, of course). Therefore, for the organization to successfully propel itself (as a Stealth Fighter) toward its goal, attention must be given to coaching the leaders and future leaders who are represented in boxes 4 through 8. Dr. Jon Warner, of Warner RESULTS Coaching, has done breakthrough work in the area of targeting executive coaching to individuals based on their Nine-Box placement.

Exhibit 11.12: A Simplified Nine-Box

Boxes 1, 2, and 3

Clearly, the individuals assigned to these boxes are generally well regarded and are worthy of receiving executive coaching attention. For those in box 3, the main focus should be helping them become ready for their next career step. For those in box 2, the main focus should be helping them lift their current performance before moving on or up. Finally, for the stars in box 1, the focus should be sustaining their focus and ensuring that they are retained.

Even though those in boxes 1 through 3 attract as much as 80-90 percent of the internal and external coaching effort, there is a definite need (as just mentioned) to pay close attention to the individuals in boxes 4 through 8 (who comprise 70-80 percent of the entire managerial population.

Box 4

Individuals in box 4 often operate below the radar because they work hard. However, sometimes hard work can disguise underlying problems, such as a leader’s inability to delegate or be a team player. This can lead to otherwise talented leaders not spending enough time developing their own inner and outer core, which can be a big problem if they manage many people. In essence, despite being recognized as top performers in their current positions, these individuals are not regarded as having high potential.

Box 5

At the other corner of the grid is box 5. These individuals are often far more visible or known in the organization because they likely demonstrated high potential earlier in their careers (and therefore have been promoted) and/or continue to show flashes of even higher potential. However, despite their tremendous upside, these individuals are presently underperforming. Coaching is critical here because it can ensure that any lack of confidence or competence is identified and managed. Often these individuals need help in building their confidence or experience. With the help of a coach, they can learn how to perform effectively.

Box 6

Individuals in box 6 are different from the others in the Nine-Box because they may be capable of moving into any of the other boxes on the grid quite quickly. Some individuals in this box may be on the way up or on the way down. Only development and time will tell. However, whether moving up or down, people in box 6 share the same challenge: They have to prove to higher management that they are solid performers with solid potential.

Because approximately 25–30 percent of the managerial population may be assigned to box 6, coaching interventions are critical for two reasons. First, individuals may need direct and ongoing help to move forward (e.g., planning, organizing, communicating more effectively, etc.). Second, these individuals may easily start to slip backward if they are not coached, quickly resulting in a competence shortfall by those they manage or deal with. Even those in box 6 may start to feel underappreciated and overlooked. Being such a large population, they present a critical need for more coaching time than they typically receive.

Box 7

Although individuals in several of the boxes can block the progress of others, individuals in box 7 are more likely to block others simply because they have low or even no potential movement and are making minimal contributions. Similar to those in box 4, these individuals can operate under the radar and may become visible only when a high-performing/potential individual working with them criticizes them, or they lose a valued employee to a competitor. A coaching intervention may be critical to ensure that there are no immediate at-risk issues resulting from this individual’s contribution shortfalls. Typically, these individuals respond well to coaching, especially if the coaching brings new ideas they have not considered.

Box 8

These individuals have the capacity to contribute but do the minimum when it comes to performance and results. Individuals in this box are often highly intelligent but may see their work to be repetitive or not challenging enough. They may see themselves as merely passing through and therefore fail to hold either themselves or others accountable for getting things done efficiently and effectively.

From a coaching perspective, this box represents a large population of people on the overall grid. The coaching focus should be aimed at creating more engaging and challenging work.

Defining Action Steps

On-the-Job Development

• Learning by doing

• Reading assignments

• Job rotational assignments

• Presentation to a senior executive

• Assigned to lead a project

• Interviewing senior executives who possess needed talents (reference reservoirs)

• Assessment center activities/simulation-based training

Competency-Based Training Courses

• Internal or external course(s) designed to enhance specific competencies (e.g., emotional intelligence)

Leadership Development Programs

• Are designed to provide leaders with a common learning experience.

• Allow trainees to connect and learn from other leaders inside or outside the organization.

• Typically provide high-potential leaders with three to five days of intensive leadership training.

Typical High-Development Practices

• Increase decision-making authority.

• Expose trainees to a new functional area.

• Are an opportunity to launch a new project.

• Turn around a business.

• Increase direct reports (number and quality).

• Include executive coaching.

• Include courses in emotional intelligence/people management.

The Roles of Stakeholders/Mentors in Building Positive Lasting Change

Given that your coachee has received valuable feedback and has targeted development actions, you should encourage him or her to follow up with their stakeholders to encourage ongoing support and development. This is usually completed during one-on-one meetings (see Exhibit 11.13) There are multiple benefits:

• It demonstrates a willingness to listen to input and respond appropriately.

• It promotes a culture of candor and openness.

• It models a continuous improvement mindset.

• It invites others to support the coachees to help them carry out their action plans.

Typical Agenda for a Stakeholder/Mentor Meeting

• Introduction:

• Thank them for taking the time to provide feedback.

Exhibit 11.13: Stakeholder/Mentor Letter

Dear Mentor/Stakeholder:

Thank you very much for being a critical stakeholder and partner in my quest to become the absolute best leader I can be. I realize I cannot achieve my goal without you—your valued input, guidance, support, and feedforward. That’s right: not feedback but feedforward! More on this below. I have prepared a list of suggestions that I hope you will consider prior to our meeting(s):

• Let go of the past. The 360s are done, the coach interviews have been completed, and the assessment results have been debriefed with me. When we continually bring up the past, we demoralize the people whom we are trying to help change. Whatever happened in the past happened in the past. It cannot be changed. By focusing on a future that can improve (as opposed to a past that cannot improve), you, the key stakeholder, can help me achieve positive change. (I have learned from my coach that this process is called feedforward, instead of feedback). Example: Instead of saying, “I agree you need to improve your decision making. I remember when you …,” instead say, “I agree you need to improve your decision making. Let’s discuss some concrete strategies that you can start implementing now that will help you achieve that goal.” Even if you don’t know me very well, using a feedforward approach will enable you to still talk about future-oriented strategies that I can start implementing—immediately.

• Be helpful, supportive, and honest.

• Pick something to improve yourself. I will be very honest with you about what I plan to change about my leadership style. As part of this process, I will ask for ongoing suggestions. I would suggest that you, as a stakeholder, select an area that you want to improve in and to ask me for feedforward suggestions on how you can achieve your goals. This makes the entire process a two-way instead of a one-way process. This helps you, the stakeholder, act as a fellow traveler who is also trying to improve. If every manager in our organization worked with their stakeholders and mentors in this way, think of the massive positive changes we would be making, individually as leaders and collectively as a leadership team. Thank you very much for your support and consideration of these important points.

Best Regards,

– Express to them how helpful the entire process has been to you.

– Orient them to what you have accomplished to date.

– Indicate that your goal through executive coaching is to become a stronger and improved professional, leader, and person and, as part of that, you recognize that you cannot achieve this goal without the input, guidance, and support of those who are closest to you.

– Tell them that you consider them one of those close/valued professionals and that therefore you would be most appreciative if they would consider providing you with input, guidance, and support, both in terms of listening to and reshaping your IDP as well as providing ongoing support, guidance, and input.

• Share results:

– Identify two strengths.

– Identify two development needs.

• Share action plans:

– Share anticipated outcomes based on actions.

– Ask for feedforward suggestions on the plan.

– Request ongoing support and feedforward.

– Ask them to share what they are working on as leaders and offer your feedforward suggestions.

– Thank them again.

LeaderWatch™ Abbreviated Surveys and Follow-Up

LeaderWatch™ Abbreviated Surveys are a tool you can use to measure the progress of your coachee in several defined development areas. By measuring your coachee’s progress, you can help ensure that targeted behaviors are changing. This monitoring is not only essential to ensuring the success of your coachee, it is a great way to prove and verify the ROI associated with the coaching experience. We recommend that this tool be distributed three months after the IDP is finalized and then every three months thereafter. The process of administering a LeaderWatch™ Abbreviated Survey is beneficial in two ways: (1) it reinforces to the stakeholders that your coachee is dedicated to becoming the best leader possible, and (2) it actively involves the stakeholders in your coachee’s ongoing development as a leader. That said, it is vital to keep the LeaderWatch™ Survey simple and time efficient. Key steps are:

1. Distribute the survey to stakeholders (Exhibit 11.14).

2. List the two or three development areas your coachee is working on.

3. Review responses and summarize data (ensure confidentiality).

4. Present the results to your coachee and then the coachee’s manager and sponsor.

Exhibit 11.14: The LeaderWatch Abbreviated Survey Tool

5. Remember to emphasize the progress made (recognition) but also the need for never-ending progress.

Final Thoughts

I hope you will be able to put the information in Talent Leadership to immediate use in your organization. To further assist you in this pursuit, I would like to conclude this book by offering what I call my Twenty 2020 Concept. These are the 20 definitive talent leadership and executive development elements/practices that your organization needs to implement and execute now in order to successfully mitigate operating risk and to ensure its viability and survival through the year 2020 and beyond:

1. Promote leaders and identify future leaders and position them in the leadership pipeline based on the relevant competencies required for success now and into the immediate future (i.e., 5 to 10 years).

2. Identify at least two candidates who are ready now and two future candidates for each mission-critical role throughout the organization.

3. Promote top-shelf executive talent that is vetted using multimethod executive assessment and senior executive opinion.

4. Reduce top-shelf executive talent turnover with thorough onboarding when introducing an executive to a new position and by having regular career and development discussions, ensuring that each executive is nurtured, properly challenged, and developed with a strong emphasis on coaching and mentoring.

5. Establish a succession management process that is perceived to be fair and open. A critical factor in retaining high-potentials and emerging leaders is letting them know they have been identified as valued assets and then following through with targeted coaching and development opportunities. It is likewise as critical to let your valued assets know (as well as those who are not yet on any lists) that lists are not fixed and that there is no guarantee of any future promotion if they are identified as high-potential. The only guarantee you must follow through on is that you will commit resources to help your valued assets become the best they can be.

6. Insist on user-friendly succession management processes and tools.

7. Effectively and correctly identify high-potential and emerging leaders using multimethod executive assessment.

8. Implement talent review meetings that effectively integrate performance, objective assessment data, potential, and readiness information.

9. Conduct talent review meetings to accurately calibrate a candidate’s potential and readiness based on integrated diagnostic information.

10. Ensure talent review meetings, include isolating development plans for successors and high-potentials.

11. Include talent review meetings that focus on leveraging diversity and setting development plans/goals for minority successors.

12. Ensure that senior management is involved and supports the executive development and succession management process.

13. Create executive development and coaching programs that are linked to the overall strategy of the company as well as the leadership competencies required for success now—and into the future—based on current and anticipated market conditions and resulting business strategy.

14. Set executive development programs and coaching goals that are linked to objective assessment results.

15. Create a way for executives, their managers, and human resources to track developmental progress; don’t be afraid to course-correct high-potential lists based on recalibrated performance, potential, and developmental progress information (i.e., high-potential lists should be fluid, meaning that executives can enter or exit the high-potential pool based on their development progress).

16. Drive multifaceted (i.e., 70–20–10) executive development programs.

17. Have executives and future leaders create individual development plans (IDPs) based on a combination of subjective feedback from their manager, objective assessment, results, and results from succession planning meeting with the help of a coach.

18. Arrange for executives and future leaders to partner with stakeholders and mentors in creating their IDPs.

19. Have a personal passion and plan for ensuring that leadership development efforts produce an effective return on investment.

20. Possess a passion and plan for ensuring that leadership development is a continuous process, not event driven.