Getting Learners to Learn

Chapter highlights: |

|

This chapter begins with three common scenes in which we find a knowledgeable person attempting to teach a novice learner. As you read each one, ask yourself the following questions:

- Why isn’t this working?

- Is it anyone’s fault?

- Have I ever been in a similar situation, either on the giving or the receiving end?

- What was the result?

Scene 1: Driven to Distraction

| Father: | All right, Gail. Now press on the clutch—no, not the brake, the clutch— with your left, not your right, foot. | |

| Gail: | Should I do it fast or slow? | |

| Father: | Push down fast, but not too fast. Now, move the gearshift into first gear. Then ease up on the clutch as you give it gas. | |

| Gail: | Do I move the gearshift fast or slowly? Do I use my left foot for the clutch? And do I push it fast or slowly? | |

| Father: | It doesn’t matter. For the gearshift, I mean. And what did you ask about the left foot? Of course, the left foot. And do it … no … no … you’re giving it too much gas! | |

| Gail: | Daddy, the car is bouncing. What do I do now? | |

| Father: | Hit the clutch! Stop pressing on the gas! Hit the brake! Oh no! Now look what you’ve done! | |

| Gail: | I hate driving! I hate you! I quit! |

Scene 2: As Easy as Cherry Pie

| Junior:: | Grandma, I love your cherry pie. Can you tell me the recipe so I can make one? | |

| Grandma: | Well, I’ll try. You need lots of flour, some sugar, eggs, and milk. | |

| Junior: | Do you need cherries? | |

| Grandma: | What a silly question! Why, of course. You can’t make cherry pie without cherries. |

|

| Junior: | How much flour? And sugar? And all the other stuff? | |

| Grandma: | Well. I guess you need about three cups of flour … or is it four? And the sugar … let me think … you know, I can’t say for sure. Isn’t that strange? And I’ve been baking these pies for more than 60 years. |

|

| Junior: | You mean you can’t tell me how to make a cherry pie, Grandma? |

Scene 3: Electrified

| Experienced customer | Now we come to a really important part of your job— | |

| agent (CA): | informing customers of a scheduled electrical shutdown. | |

| Novice CA: | Do I call them all up? | |

| Experienced CA: | No … yes … no. Well, sort of. I mean not you personally. Well, sort of personally. You record a voice message and send it out. | |

| Novice CA: | How do I know whom to call? | |

| Experienced CA: | By accessing the customer database and matching the affected transmission lines with the appropriate customer electrical address. | |

| Novice CA: | And how do I know which transmission lines are affected? Also, where’s the database? | |

| Experienced CA: | (losing patience) From the work orders. And the database is in the computer. | |

| Novice CA: | Will I find their street addresses and phone numbers there? | |

| Experienced CA: | (exasperated) No. Only their electrical addresses. You know, the alphanumeric code related to a transformer or cut-off point! | |

| Novice CA: | Huh? |

Let’s analyze what happened in those three scenes. You can compare your answers to the questions we asked you up front with our answers.

Why isn’t this working? In all of the scenes, it is obvious that learning isn’t advancing very quickly. In each case, we had a true subject matter expert (commonly known as an SME) and a novice learner. You would think that if these SMEs know so much, they should have no trouble making the other person learn. But it’s not happening because experts and novices do not process information in the same way. In fact, the greater the expertise, the less the expert thinks like a novice learner.

Surely, you have had someone give you directions in a town or location that you’ve never visited before. The dialogue goes something like this:

| Direction giver: | You get on Mill Creek Highway and head west for a few miles until you see School Road. Get off and take it north for, oh, a couple of miles to the Fairlane strip mall. Just a block before, you’ll turn into a small lane—it’s a bit hard to see because of the trees, but there’s a Johnny’s Pizza just behind it. | |

| Direction taker: | (head swimming) Where’s Mill Creek Highway? | |

| Direction giver: | You’re on Mill Creek Highway. | |

| Direction taker: | But it says Highway 10. | |

| Direction giver: | Yep. That’s Mill Creek Highway all right. Just follow my directions, and you can’t miss it. |

And have you missed it? You can see that how the expert direction giver views his world differs from the way the novice direction taker sees it. Stand by—the problems intensify before we finally navigate our way through them.

Is it anyone’s fault? The succinct answer is “no.” In each scene, including this last one, both parties desire a successful outcome. Both are fully motivated and actively engaged in the teachinglearning process, but somehow things fall apart.

What was the result? Learning breakdown. We have yet to meet someone who has not participated in one of these frustrating episodes. There is a prevalent belief that the best way to learn something is to ask an expert, despite the fact that research demonstrates, time and again, how differently experts and novices view the world—and, more specifically, how something should be learned.1

Here’s a good example: In a classic research study, novice and expert chess players were shown chess games in progress, with pieces spread all over the board. The board and pieces were then hidden after several seconds, and both the experts and the novices were asked to set up the chess pieces to reproduce exactly what they had seen. Who do you imagine more accurately placed the chess pieces?

- expert chess players

- novices.

The experts did far better. They perceived patterns, chunked the information, and didn’t clutter their shortterm memories with detail. Novices, focusing on individual pieces, fared poorly. The two groups viewed the world in markedly different ways.2

Different Types of Knowledge: Declarative and Procedural

Here’s a challenge for you. You most likely live in an apartment or house. You’re there every day, or at least frequently. To a certain extent, you are an expert on your home. In the box below, write the number of windows in your home. If you are at home, don’t go around physically counting. Access this information from your memory. Accuracy is important, so take your time.

Unless you recently replaced or bought coverings for all of your windows, you probably didn’t have the answer instantaneously. In our experiments we find that people come up with the answer the same way you probably did. First, you pictured your home. Then you wandered through it mentally. If there were levels, you went floor by floor. If we were watching you, we probably would have seen your eyes go out of focus and then actually move as you “looked inward” and walked through your home. We might even have seen your lips moving as you counted windows. That is very normal. But why couldn’t you simply state the number of windows instantaneously? After all, you’re an expert on your home. The answer to that question addresses the core of the major problem in each of the earlier scenes. Keep reading to discover why.

Become familiar with these two terms: declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge. They are key to unlocking many learning mysteries.3

Become familiar with these two terms: declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge. They are key to unlocking many learning mysteries.3

The human brain is amazing. It is an intricate system of millions of individual elements, each doing its own thing. Yet, somehow it all works. The brain is not a coherently designed and engineered organ. We are born with a brain that carries out myriad simultaneous and independent activities. Most parts of the brain are totally oblivious of the activities going on in other parts. Among the activities the brain conducts is the processing of information for learning. That information, which comes from the outside world, is taken in and transformed into knowledge. The knowledge we possess that allows us to name, explain, and talk about matters is called declarative knowledge. No other species on earth even vaguely comes close to humans in our ability to learn and use declarative knowledge.

Look at these four items and put a checkmark beside the actions you imagine require declarative knowledge:

- 1. Name the capital of France.

- 2. Ride a bicycle.

- 3. Explain the causes of World War II.

- 4. Navigate a database.

Items 1 and 3 are examples of declarative knowledge (name, explain, and/or talk about). Items 2 and 4 are examples of another important category: procedural knowledge. That type of knowledge enables us to act and do things, to perform tasks. Unlike declarative knowledge, which is almost exclusively restricted to humans in any sophisticated form, procedural knowledge is readily available to all animals.

So, how related are declarative and procedural knowledge? Let’s figure this out for ourselves. Naming the number of windows in your home required declarative knowledge. Although you are an expert about your home, you didn’t have the number readily available in declarative form. Instead, your expertise is in walking through your various rooms and locating windows—procedural knowledge. You can “do,” but not readily “say.” This is because humans process declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge very differently.

Can you ride a bicycle? Can you maintain your balance on the bicycle? Most people answer “yes” to both questions. Now explain exactly what your body does to keep the bicycle from falling down. You might mention pedaling, moving from side to side, holding on to the handlebars, and so forth. When we probe bicycle riders about exactly what they do to keep the bike steady, however, they end up saying, “I can’t explain it. I just do it.”

Most expertise develops that way. The majority of what we have learned to do has been acquired without words. By trial and error over time, we simply have built up the capability to do it. And here’s where that presents a problem in training: Organizations commonly approach someone who knows how to do something (an informal definition of an expert) and ask him or her to teach novices how to do it.

Now for a paradox: These experts have acquired their capability over time and with practice. In other words, they possess most of their expertise in the form of

(select one):

- declarative knowledge

- procedural knowledge.

In almost all cases, their expertise is in the form of procedural knowledge. But when asked to train others, usually in a short amount of time, they are expected to transmit their knowledge by explaining, giving examples, and providing contexts and cases. In other words, they teach (select one):

- declaratively

- procedurally.

The experts deliver declaratively. Then the learners have to convert the declarative knowledge from training back into procedural knowledge to meet the expectation of being able to “do” things in a new way. Simple and vivid examples of this are when a golf pro tells you how to hit a golf ball straight or a skating coach tells you how to make a quick stop when rollerblading. Much easier said (declarative) than done (procedural)!

Research on learning tells us that what we learn declaratively cannot be readily transformed into procedural knowledge unless we already possess similar procedural knowledge. The reverse is also true. Procedural knowledge does not easily convert to declarative knowledge. Therefore, although you know your home well and you mentally walked through it to count the windows, you still may have missed a few.

This conversion difficulty also accounts for the problems in our earlier scenes:

- Daddy can’t convert his cardriving knowledge (acquired procedurally) to the right declarative language. Even if he could, Gail can’t readily absorb his declarative explanations and convert them into procedural capabilities.

- Grandma knows how to bake a cherry pie, but can’t recite the recipe.

- The experienced customer agent can inform customers of electrical shutdowns, but has obviously confused his novice learner.

- The local resident can’t readily speak the clear directions that will help the tourist find his way from Mill Creek Highway.

Here’s a fun exercise that demonstrates how expertise that lets us do things (procedural knowledge) simply does not provide all the declarative details. In fact, we often don’t even have a (declarative) explanation for how to do it right (procedurally).

Correct the grammar in these two sentences:

When I were in Paris, I ate a croissant with every meal.

__________________________________________________________

If I was in Paris, I would eat a croissant with every meal.

__________________________________________________________

You most likely changed each one correctly. (When I was in Paris, I ate a croissant with every meal. If I were in Paris, I would eat a croissant with every meal.) Unless you are a grammar specialist and have the declarative knowledge, it is unlikely that you can explain (declaratively) why you corrected each of the above (procedurally).

Here is the declarative explanation: “When I was in Paris…” states a fact. This requires use of the indicative mood in English grammar. The form “was” is the correct first person singular past perfect indicative form. Yay! However, “If I were…” states a possibility, which in formal English grammar requires use of the subjunctive mood and “I were” is the correct first person form. You did it (procedurally)! Did you know all of this (declaratively)? Ah well, be that as it may, you probably get the point.4

In our testing of this exercise, very few people knew why each form was right. Several knew about the subjunctive or spoke about “conditional” situations, but no one absolutely nailed it despite the high rate of procedural success. (Incidentally, in the United States saying, “If I was…” is informally acceptable in the spoken form—more declarative information.)

With an awareness of the kind of knowledge we want our learners to acquire— declarative or procedural—we can adjust the way we present learning material to them. If it’s talkabout knowledge (for example, what or why information, fact recall, or names), we can create activities that provide what must be learned and have our learners practice declaratively. If we want them to acquire do and use types of knowledge, our strategy changes to a more handson approach. The bottom line is to match what our learners have to learn with the mode of training/ instruction/education we employ. (We’ll cover this in a more planned and organized fashion in chapter 6.)

One final note on these two types of knowledge. Gaining procedural knowledge eventually allows us to gain fluency in doing things without having to think about what we are engaged in. Running a photocopier or processing an insurance claim are procedural tasks that we can expertly deal with through practice. However, what if we change the model of photocopier to a more computerized version, with buttons and viewing panels in different places, or what if the insurance claim forms change and the rules governing how they are to be handled alter?

Methods to produce efficient procedural knowledge result in rapid fluency, so long as the conditions remain the same. Declarative knowledge allows us to generalize to new circumstances through explanations. It may slow down the performance, but it permits adaptation to new requirements. We may want our soldiers to assemble and disassemble a certain model of firearm they regularly use to the point of automaticity (act perfectly without thinking about it). What if they suddenly find themselves on the battlefield with a different firearm? Without some form of declarative, mental rules about how a variety of models work, they may get lost trying to make sure it works, flounder about in confusion, and expose themselves to increased risk.

The bottom line is that while each type of knowledge requires a specific form of instruction for desired performance, often a combination of both—explanation and practice—works to produce a more effective result.5

Key Ingredients for Learning

Cognitive psychology research suggests that three major factors influence how much and how well we learn: ability, prior knowledge, and motivation. Let’s examine each of these in detail.6

Ability

The capacity with which we were born that enables us to acquire new skills and knowledge varies among individuals. Just like height or musculature, we arrive on the scene with a certain mental (or learning) potential. It may be unfair but some of us are born taller, slimmer, more physically attractive, or able to learn more quickly than others.

This general learning ability is the intellectual capacity with which we are genetically endowed. It strongly influences our overall capability to learn. Note the word “general.” Those who have greater general ability grasp more quickly, comprehend more easily, and recall more efficiently than others do. They seem to get it faster and play it back or even enhance it better than those not as intellectually able.

Recently, many nuances have been added to the construct ability and its almost synonymous cousin, intelligence (usually defined as the ability to think about ideas, analyze situations, and solve problems, which is measured through various types of intelligence tests). While general ability is usually broken down into nonverbal ability, concrete reasoning ability, and abstract reasoning ability, researchers have stretched further into “multiple intelligences.”7 Educational psychologists now view individuals as multifaceted and have created tests to measure verbal linguistic, mathematical logical, musical, visual spatial, bodily kinesthetic, interpersonal, naturalistic, and even existential “intelligences.” In all cases, these appear to be considered inherent characteristics.

Obviously, like musculature, the way in which ability is fostered and trained can seriously affect how well one’s cerebral (and other) capabilities grow and develop. As trainers, it is important for us to note that learners vary in their ability to learn. We have to be aware of the differences in ability and compensate for those who do not learn as rapidly as others. We also have to keep the more generally able learners constantly stimulated and challenged to maintain their focus.

Although we all possess general intellectual ability, we also are endowed with specific abilities at birth. An ear for music, a golden voice, athletic agility, and artistic talent are extremely valuable specific learning abilities that are more important than general intellectual capability in certain instances. The innate, specific abilities of Michael Jordan in basketball, Barbra Streisand in music, and Pablo Picasso in art have played enormous roles in allowing those “learners” to achieve far beyond others who may have received the same “training.”8

Prior Knowledge

General and specific abilities greatly influence learning, but how much a person already knows about what he or she is being taught also strongly affects learning.9 A brilliant philosopher or mathematician may not learn as well as a less intellectually gifted carpenter when receiving some new piece of instruction about carpentry. Prior knowledge helps the learner acquire additional knowledge or skills more rapidly.

Let’s test that assertion. Below are two French verbs—one a regular verb, the other irregular. Which one is the irregular verb?

- danser

- tenir.

In chapter 2, you learned that French regular verbs end in “er.” If you picked that up then, you probably correctly selected tenir as the irregular verb above. Your prior knowledge helped here. If you missed it, that’s OK. You didn’t possess the prior knowledge, and you had to work harder. So, the more you know about something, the easier it is to acquire additional knowledge and skills in that subject.

Motivation

We all have seen the power of high motivation—the desire to achieve something. We also have seen the reverse: Those who don’t care, have no drive, or seem to lack interest in learning rarely achieve proficiency in new knowledge and skills. We often talk about motivation and its importance, but what is it? Motivation appears to be affected by three major factors: value, confidence, and mood.

Value. The more we value something, the more motivated we are about it. In figure 41, we have placed motivation on the vertical axis and value on the horizontal. Notice that as the learner attributes a greater value to what is to be learned, motivation increases. If you value being seen as someone who knows opera or football, you will become more inspired (that is, motivated) to learn about it. The higher the value attributed to what is to be learned, the greater the motivation.

Confidence. If you feel totally inept in your ability to learn something, how motivated are you to try?

- highly motivated

- unmotivated.

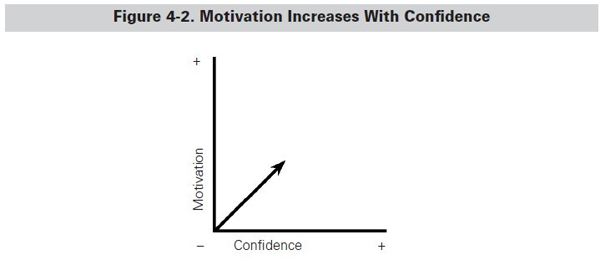

The answer, of course, is unmotivated. Low confidence in learning is strongly correlated with low motivation. As the confidence of the learner increases, so does the motivation, as illustrated in figure 4-2.

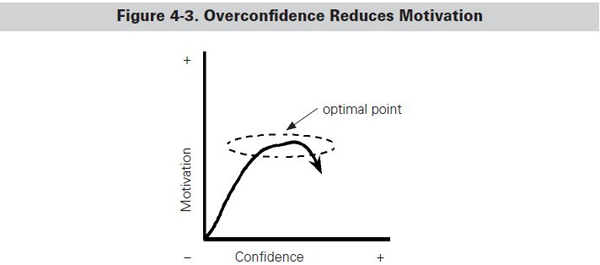

Overconfidence, however, leads to a decline in motivation. If the learner feels that “this is so easy, I don’t even need to try,” motivation plummets, as shown in figure 4-3.

The optimal point of motivation is where the learner has enough confidence to feel she or he can succeed, but not so much that the desire to learn declines. This

high point of motivation is one of challenge (“I have to work at it to succeed”) and security (“if I do work at it, I know I can succeed”).

Mood. We all know that if we’re not in the mood, our motivation to learn goes down. Personal feelings affect our mood as does the atmosphere of the learning and working environment. A positive learningworking environment tends to improve a person’s mood and, hence, his or her motivation as illustrated in figure 44. But a frivolous or manic mood might have bizarre and unpredictable effects on motivation. A positive mood is one in which you are open and optimistic without being flighty or euphoric.10

To summarize this section on the three key factors that affect learning—ability, prior knowledge, and motivation—trainers are generally content people placed in the role of helping people acquire sufficient knowledge and skills to perform something they don’t know how to do. Asking them to step outside of their area of

expertise and become totally “customer focused,” that is, learner centered, is a challenge. However, trainers can derive enormous satisfaction when they see that their charges “get it.” By watching learners and sizing up how well they can absorb what the trainer provides, by acknowledging and shoring up prior knowledge, and by exemplifying how worthwhile it is to achieve what the trainer is helping them to attain he or she will experience the high that comes from their successes. If training were just a telling task, everyone would excel at everything.11

Adapting for Differences in Ability, Prior Knowledge, and Motivation

Ability, prior knowledge, and motivation strongly affect learning. Can we, as trainers, instructors, educators, or managers of learning influence all of these? Fortunately, the answer is “yes.”

Ability

Although we can’t alter a person’s ability, we can observe and detect his or her strengths and weaknesses. As a result, we can adapt the learning system by taking the following measures:

- adjusting the amount of time for learning

- providing more practice for those who require it

- simplifying and breaking learning into smaller chunks for those who are experiencing learning difficulties

- providing additional support for those who need it

- including activities with greater challenge for those who learn more quickly

- providing alternative learning paths.

Computerized testing and assessment capabilities built into modern learning management systems, which are now very present in medium and large organizations, make determining the ability levels of learners somewhat easier. Performance tests can be created and deployed. Time to acquire skills can be tracked. Study of a learner’s learning choices and paths can also provide clues. The purpose of all of this, of course, is to better determine learner ability and provide necessary and sufficient instructional support.

Those are only a few ways of compensating for differences in learning ability. The key is to observe and acknowledge such variations and make suitable modifications to the instruction, whether through live interaction with trainers and/or peers, online, from a book, or through practical experiences on the job.

Prior Knowledge

If learners are missing prerequisite knowledge and skills, we can make adjustments to these gaps by

- creating prelearning session materials to close the gaps

- building special supplementary learning events prior to or concurrent with the learning sessions

- creating peer tutoring pairs and teams to provide mutual support for overcoming gaps

- providing overviews and summaries of prerequisite content in outline or summary form

- directing learners to online sites that can fill knowledge or skill gaps

- assigning tasks and experiences that fill in missing background and knowledge.

That’s only a starter list. Offering sources of knowledge or resources for acquiring prerequisite skills can help bring learners up to speed quickly.

Motivation

Based on the three major factors that affect motivation, we can overcome deficiencies in the following ways:

- Enhancing the value of what is to be learned. Show the learners what’s in it for them. Provide examples of benefits. Show them admired role models valuing what is to be learned. The more the learners perceive personal value in what they are learning, the more motivated they will become.

- Adjusting the learners’ confidence levels with respect to the learning content. Be supportive to build their confidence that they can learn but provide sufficient challenge so that they don’t become overconfident about it.

- Creating a positive learning atmosphere and work climate. The more open and optimistic the context you build, the more open and positive the learners will be, and that leads to greater motivation and to learning. Watch out for threat levels during training. Stress that breeds anxiety and fear of failure severely dampens learning.

Keep in mind that all learners are different. Whether as a group in a classroom, as a team at the worksite, or individually through a manual or via computer in real time or asynchronously, they come to us with widely differing characteristics. Training, in its broadest sense, is a compensation for what each of our learners lack.12 Just imagine what our job would be if all of our learners came to us with elevated general and specific learning abilities, vast prior knowledge, and tremendous motivation. Would we (check one):

- teach until they learned what we provided them?

- give them the learning resources and then get out of their way, providing only feedback and reinforcement as they progressed?

If you checked off the second box, you’re right. Talented, knowledge able, motivated learners only require learning resources and useful feed back that is corrective to get them back on track when they have erred and confirming to let them know when they got it right. The less they possess of ability, prior knowledge, and motivation, the more we trainers have to work to compensate for what they lack.

If you checked off the second box, you’re right. Talented, knowledge able, motivated learners only require learning resources and useful feed back that is corrective to get them back on track when they have erred and confirming to let them know when they got it right. The less they possess of ability, prior knowledge, and motivation, the more we trainers have to work to compensate for what they lack.

Yes, that’s our job—compensating for what learners don’t have, managing the learning context, and providing feedback and rewards for success.

Remember This

Let’s close this chapter with a summary of the main points. Of course you will have to do most of the work. Select what you believe to be the best word to fit each sentence below. Cross out the inappropriate options. Our role will be to offer feedback and provide a reward. We’re just getting out of your way.

- Experts and novices treat the same content information (similarly/differently).

- The size of a chunk of information is (larger/smaller) for a novice than for an expert.

- An expert mechanic has acquired most of her expertise (declaratively/ procedurally).

- The same mechanic, when assigned to instruct a group, usually transmits her expertise (declaratively/procedurally).

- The mechanic-instructor’s learners are then expected to go back to the job and apply the new knowledge (declaratively/procedurally).

- Often a combination of both declarative and procedural instruction— explanation and practice—works to produce a (more/less) effective result.

- Three key ingredients for learning are ability, prior knowledge, and (motivation/ information).

- The (more/less) a learner values what is to be learned, the higher his or her motivation.

- Highly motivated, able learners with excellent prior knowledge require (more/ less) teaching.

- Training activities are a compensation for what the learner (possesses/lacks).

Now here’s our feedback:

- Experts and novices treat the same content information differently. Novices’ shortterm memories rapidly fill with new content, and they easily plunge into information overload.

- The size of a chunk of information is smaller for a novice than for an expert. An expert’s chunk may contain a great deal of condensed information. For novices, each detail frequently becomes an individual chunk.

- An expert mechanic has acquired most of her expertise procedurally—by doing rather than by naming and talking about what she has done.

- The same mechanic, when assigned to instruct a group, usually transmits her expertise declaratively. She talks about, describes, and explains what she thinks she does in her work—and that may not be fully accurate or complete.

- The mechanicinstructor’s learners are then expected to go back to the job and apply the new knowledge procedurally. The aim is to get them to do the job. What a paradox!

- Often a combination of both declarative and procedural instruction—explanation and practice—works to produce a more effective result. The declarative portion provides a framework for the application. It can help learners deal with new situations, adapting procedural knowledge they have acquired.

- Three key ingredients for learning are ability, prior knowledge, and motivation. At this point, you’ve got it. You require no further explanation.

- The more a learner values what is to be learned, the higher his or her motivation. There is a straightline relationship between perceived value and motivation.

- Highly motivated, able learners with excellent prior knowledge require less teaching. Our instruction should provide only what the learner is lacking.

- Training activities are a compensation for what the learner lacks. The greater the abilities, prior knowledge, and motivation the learners possess, the less they require of us. We increase our support appropriately.

Organizations generally select trainers on the basis of subject matter expertise, and in this chapter we have seen how that leads to instructional problems. Content is not enough.

We are dealing with adult learners. Their success is our success. So let’s proceed to the next chapter to discover how we can get into our learners’ heads and hearts to help them learn.