11 Abstracts

Photography took the place of eighteenth and ninteenth century naturalistic painting. Starting with impressionism, painting went in its own direction and has increasingly liberated itself from a natural way of viewing the world. The exception was the realistic movement that emerged from naturalism. In painting, the realistic movement had the task not only to depict reality, but also to represent deeper traits of reality.

Photography had taken over the representation of nature, but photography also had to liberate itself from the restricted representation of reality. Thus, the movement to take photography out of the convention of realistic representation began at the turn of the century with the Russian photographer Aleksander Rodchenko and in the 1920s with Hungarian photographer László Moholy-Nagy and his famous Photograms.

It may seem that an endless variety of abstraction methods have been used in photography. However, what does abstraction really mean? According to the dictionary abstraction is “detachment from material things.” Thus, abstract thoughts start detaching themselves from objects and developing their own inner life, and exactly the same holds true for pictures. If painting makes reality into an abstract and presents a new creation of shapes and colors, then the fact is that photography is always the portrayal of an objective world. And yet for photography, the concept of abstraction also means a detachment from the world of objects. When, for example, the abstract structure of a picture becomes the meaning, photography has detached itself from the actual object. Although pictorial meaning is based on an abstract structure, as frequently stressed in the example images throughout this book, most viewers are accustomed to noticing only the pictorial meaning. Only when the subliminal pictorial structure is seen abstractly (i. e., detached from the object) and found to be interesting will the pictorial meaning become powerful. In order to test the abstract structure of a very objective photo, it’s a good idea to turn the image upside down because then it will to lose its connection to reality and its abstract basic structure will become visible to the eye. This structure is the basic pattern that pervades the image, the interplay of lines and shapes of all kinds. A master of abstract design was the painter Vassily Kandinsky. He developed an entire philosophy about how the most varied shapes could be placed next to one another to create tension. He saw this as an act of creation.

In photography, the art of good design is to work out a composition for the subjective interplay of forms that is the basis for all objects and to frame the objects with the viewfinder in such a way that an exciting abstract pictorial structure is created. In summary, meaning can become dominant over form, meaning and form can be balanced, or the abstract shape can eclipse meaning. A detailed view can sometimes tell a bigger story than a complete view can.

However, it is risky to photograph structures because one can quickly fall into rigid formal images that have lost their meaning. The photos taken in amateur photo clubs are full of these kinds of structural pictures. Although they are certainly good for practicing composition, because they train you to abstract reality, they are purely formal pictures. The pictures should be about meaning that has become so abstracted that through the photograph you come close to the nature of the respective object.

On the other hand, the abstraction may be so successful that you can see a well-known object in a new way. For example, the Dadaists declared their collages (old, ripped-off advertisements and the like) to be art and placed them in museums. They detached these old, tattered advertisement scraps from a conventional concept to see them in a new light and rediscover their tactile appeal and sensory nature.

Kurt Schwitters was a Dadaist artistic leader, and in photography, the surrealist László Moholy-Nagy was one of the masters of abstract structures. His photograms of faces were abstract, but also deeply spiritual. In his best-known portrait, he placed his own cheek on the photographic paper. The photo resembles the image of a planet in the night sky.

Just as one cell in our body contains the fingerprint of the entire body, a detail should provide information about the entire structure from which it originated and not be a formal end in and of itself.

Traces of Time

Those things in which time has etched its traces can be especially interesting. Although things like disintegrating walls or rusted-out gates often become casualties of renovation, there are still exceptions, as is the case here in Brunswick (figure 11–1). It is a mystery how time changes everything that we humans attempt to straighten out and order into a uniform monotony, converting it back to the original organic state. This image almost lets you feel the texture of the wall. It is important for a structure not to become the object itself but rather to describe a mysterious content.

The photo was taken with the normal focal length of an analog Nikon F4. Getting involved in taking shots like this invites strange looks from passers-by. Most people tend to think that the sights that everyone photographs are the ones worth looking at, and is it crucial to free yourself from this type of clichéd thinking when you are out shooting. After all, the letters on this wall tell a story about the riddle and passing of time.

Light and Shadow

The photo in figure 11–2 is characterized by a diagonal pattern of shadow lines that create a strong contrast. It shows the right side of a rusty door whose hinge can still be seen at the top. The dividing line between the door and its surrounding wall lies exactly on the vertical harmonic dividing line. The image is brought to life by the structure’s tactile appeal, emphasized by the sunlight falling obliquely on the surface, causing even the small uneven areas of the door to cast shadows. This delicate structure is overlapped by the rough structure of the two large shadows, the four small shadows, and the shadow in the upper-right corner. These long shadows lend the photo its power and tension. The door is in Jerusalem’s Old City, and the effect of time is noticeable here as well. You should not forget that when looking at such an image, you can detach yourself from the concept itself. In other words, if you associate the photo just with the concept of “old rusty door” and reduce it to this concept when looking at it, you devalue the picture. Images are much more than the linguistic concepts that attempt to explain them. The more you detach yourself from such concepts, the more you will allow an image such as this one to exert its influence through its varied textural appeal, and the more you will be able to enjoy it.

Formalism with and without Content

The small photo (figure 11–3) depicting the mirrored structures of the two towers of the Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt demonstrates what I mean by pure formalism. The interplay of the graphic lines is unquestionably interesting, and a longer telephoto lens would have possibly made it even more interesting. Yet there is something missing in an image that has been reduced to a pure graphic design, as shown clearly by the larger photo (figure 11–4). In this photo, form is no longer the content. Both towers represent the pictorial content, but now we see a figure with open arms reflected in the façade as if ready to jump off the roof of a tower. The photo has now acquired a totally different meaning that makes the observer wonder: Is it a symbol of a crucified person in AD 2001? Does such cold skyscraper architecture invite one to commit suicide? Certainly not; architecture has its imposing side after all. And yet such a photo moves the viewer to reflection, as opposed to the previous photo. Here, the symmetrical composition of the structure is only the fabric from which the content has been woven: The left side appears multilayered due to the reflection, whereas the right side is almost monochromatic.

This photo was taken with an analog camera, a 200 mm telephoto lens, and a tripod (so I could stop down and shoot with a slower shutter speed).

Structures as Fantasy Stimulators

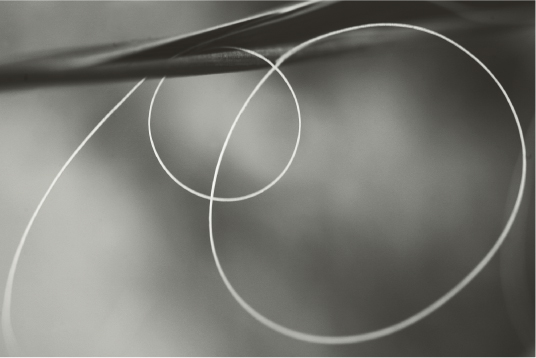

We dealt with clichéd photos earlier in this book. The structure of a tree bark (figure 11–5) is by no means a clichéd photo, but a detailed photo such as this one is so common that it has lost its appeal. Among other things, the art of abstract photographs consists of discovering something that is really unique and has not often been seen. This is more so the case with the larger photo (figure 11–6). This image shows the fibers at the end of a palm leaf, although you could be forgiven for thinking that it is a diagram demonstrating mathematical set theory. Simple, minimal shapes are often the most powerful.

When shooting macro subjects such as this, photographers nearly always have to battle with a lack of sufficient depth of field. You can increase the available depth of field by using a small aperture, although a small aperture would have given the background in this photo too much emphasis, thus distracting the viewer from the more important circular shapes in the foreground. The photo was shot digitally using a 50 mm macro lens and converted to black and white using Photoshop. Contrast was significantly increased.