13 Portraits

It is the widely held belief that a good portrait is generally a well-lit depiction of smiling, young, and dynamic faces. However, that is often superficial because the artistic depiction of a person should be more than just good compositional lighting: Every person has an individual personality and spiritual beliefs and a close relationship to his or her surroundings, which undoubtedly leave their mark. A sophisticated photograph of a person should attempt to show their individual traits (including wrinkles and spots) as well as factors from their surroundings that have influenced them. Such portrait photography can be achieved from both maintaining a certain distance and from having an intimate knowledge of the person. Obviously, it is easier to take photos of friends or acquaintances than of strangers, and it is also very tempting to mount the telephoto lens on the camera and shoot voyeuristic portraits.

Usually, a better alternative would be to photograph strangers by approaching and getting to know them. If you decide on this method, it’s a good idea to engage in a conversation before making a portrait, and you should also attempt to ask unconventional, personal questions to get to know the person a little better. When doing this, it should not be a problem to have a brief relationship with the person and to move beyond conventional conversational topics. The individual being portrayed will remember such a conversation very well, and the photographer, in turn, will get a deeper understanding of this person, which is the prerequisite for a good portrait. After such a conversation, you can bring out the camera. Ideally, it would be best if someone else would remain in the room to continue the conversation so you can concentrate on taking the photo.

There are many vivid examples of good and artistic portraits in the history of photography, but there are bad ones as well. Photography began with portraits of the bourgeoisie, and the aim was to hide, rather than show, the sitter’s real personality. In the mid nineteenth century, emulsions in photographic plates were not very light sensitive, photographers had to expose for a long time, and sitters had to remain still by leaning on columns or other objects. This resulted in numerous mediocre portraits that were taken in a partially aristocratic ambience. Disdéri was such a portrait photographer; he produced visiting cards (cartes de visite) that were not much more than souvenirs. But even for a celebrity such as Nadar, clothing was almost more important than personality because it was regarded as a second skin that sometimes said more about the person.

The innovation of faster emulsions soon liberated photographers from this kind of photography. Naturally, photographers such as Eugène Atget and Bill Brandt could now go outside, and with this development came the demand to depict people in a more realistic way. Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, and Alfred Stieglitz are good examples. “I am American. Photography is my passion. The Search for Truth is my obsession,” said Alfred Stieglitz about himself in 1921. His portraits a long with those of Paul Strand, fulfill this demand.

On hearing the word portrait, one invariably thinks of Richard Avedon’s innovative portraits of the 1970s. His minimalist portraits taken before a neutral background framed by the black film border have become famous everywhere. The harsh, pitiless lighting characterizes his photographs, with no glossing over of any kind. They are deep personality studies obsessively photographed with love. Avedon himself has given this opinion about his photos: “Youth never moves me. I seldom see anything very beautiful in a young face. I do, though—in the downward curve of Maugham’s lips, in Isak Dinesen’s hands. So much has been written there, there is so much to be read, if one could only read. I feel most of the people in my book, Observations, are earthly saints. Because they are obsessed, obsessed with work of one sort or another.” Because he was obsessed as well, he is therefore undoubtedly the most distinctive antithesis to the highly-traded portraits of the Becher School follower Thomas Ruff, who has consciously covered up any indication of an individual character in his portraits.

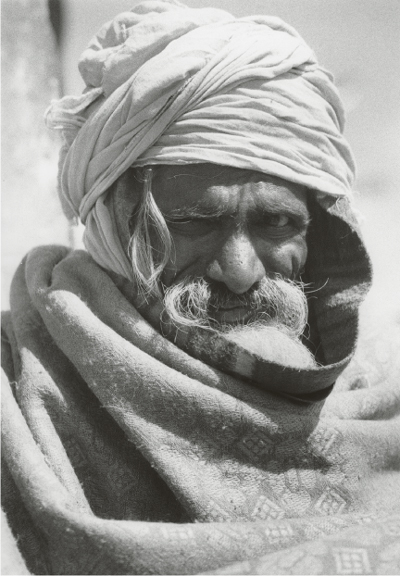

Indian Tribesman

This photo (figure 13–1) was taken at a distance from the person (in other words, with a telephoto lens). It is the result of a long stay in a remote Indian village, so it’s no quickly shot voyeuristic image. It shows an older man of the Todas tribe in southern India. The viewer should notice that the interplay of light and shadow in the man’s clothing and turban causes the photo to come to life. If an employed portrait studio photographer would have used such lighting, however, he would probably be fired, but in this kind of more sophisticated photography, you must free yourself from such conventions. It is precisely the contrasty interplay of light and shadow that emphasizes the expressive force of the person’s face. Naturally, it is essential not to allow the eyes and mouth to get lost in the shadows but to make sure they are clearly recognizable by printing the image on grade 2 (soft) paper. The fact that this person has lived all his life in a different world from ours is clearly shown here. His head and body covering, as well as his expression, show us that he has retained the customs of his remote village near Ooty in southern India where he has lived all his life. Certainly, time seems to go by very differently here, and the profound roots that this person has to his region, tribe, and family are much different than the somewhat looser affinity to life typical of the Western world. This tribesman, photographed with an analog camera and a 105 mm lens, personifies prehistory.

The Other Side of the Coin

Contrary to the previous photo, which expresses pride, security, and roots to the past, the image in figure 13–2 shows the aimlessness and loneliness of humans.

The shadows of unemployment, poverty, and neglect are nowadays an integral part of many Western societies, and for these reasons social critique photography has a great deal of legitimacy. This homeless man in New York City willingly allowed me to photograph him in his favorite spot. It was ironic, even almost cynical, that on this very day a row of posters titled “The Elegant Universe” were hanging behind him, thus opening up a whole range of interpretations for this image. The row of posters to the left suggests that they go on forever. The fact that the man was willing to allow me to photograph him indicates that he had not yet given up and had kept his dignity. Taking such a photograph is certainly a tightrope walk because on the one hand it is very important not to degrade the person with the camera and on the other hand a good portrait must also be able to tell, or at least hint at, the story of someone’s life.

The photo was taken with an analog Mamiya 645 and a 35 mm wide-angle lens.

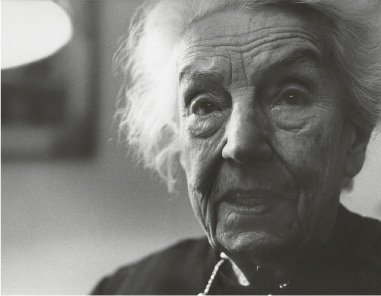

The Beauty of Old Age

According to the classical ideal of beauty, young and smooth faces are always preferred, and a portrait studio will likely use soft lenses to eliminate any hint of wrinkles. And yet, isn’t the facial landscape of the elderly perhaps more interesting than a young face? Figure 13–3 depicts a life that has stretched over 90 years and experienced, among other things, two world wars, all of which have left traces. In this image I set out to capture the multilayered character of this woman and to catch the instant that does justice to her personality. Part of the task was to emphasize and not to conceal wrinkles and uneven spots: For example, the axis of the mouth does not run parallel to the axis of both eyebrows. A conventional portrait studio would have photographed the lady from the left side to compensate for this unevenness. A photograph taken from the lower right, however, emphasizes these nonparallel axes and therefore accentuates her character.

Her expression and the slightly raised left eyebrow in the photo betray a skeptical, maybe somewhat fearful attitude, and yet the entire face expresses integrity and dignity.

The photo was taken with an analog camera using a 50 mm lens with Kodak Tri-X Pan pushed to 800 ASA. The natural interior light was sufficient to shoot with f/4 at ![]() s.

s.

Finding the Essential in the Fleeting

A good portrait captures an instant that reveals something about the person that goes beyond that instant; it is the art of good observation to recognize the essential in the fleeting. The facial expression of the woman in figure 13–4 is relaxed and rested in the brief moment captured by the photo, while her eyes look very alert and a bit mischievous. Looking at her, you would recognize personality characteristics such as sensitivity and intelligence. The special attraction of this photograph obviously lies in the fact that the woman resembles the mannequin in the display window—the young, blonde, pretty and a bit naive cliché—and she even has a similar haircut. This obvious parallel of an external attribute formally invites the viewer to make all kinds of comparisons, especially to realize that the woman does not really fulfill the cliché mentioned above.

The photo was taken digitally with the 32 mm focal length of the zoom lens and converted to a black and white using Photoshop.

Digital photography has enormous advantages for portraits because one can recognize facial expressions quite well in the camera display with the enlargement mode and, therefore, can correct unexpected surprises immediately by reshooting the photo.

Woman’s Fate in India

Compared to the fate of Indian boys, the fate of Indian girls is even less according to their wishes. Girls are, first of all, less welcome because parents must later pay a sizeable dowry, and second, the birth of boys is regarded as God’s blessing. The young girl in figure 13–5 is also from a world that is alien to us, from the rather poor Indian state of Orissa. Although she is 10 years old at most, she already has the expression of an adult, even that of an older woman. Without showing it, the photo tells a story of child labor, poverty, and oppression already evident in early childhood. It can readily be seen in this image that this girl has prematurely lost her childhood innocence. Her expression is not caused by the act of posing for the camera; it was the same before. If I had encouraged the girl to smile, I would have had a more cheerful but less sincere photo. This photo critically shows once more a sociological problem by not stopping at the so-called superficial beauty. The interplay of light and shadow intensifies the expressive force of her face. Needless to say, it was important in the photographed image to retain definition in her eyes and mouth, so the photo, which was taken with an analog camera, was printed on soft paper (grade 2).

This portrait was taken with the 105 mm telephoto lens.

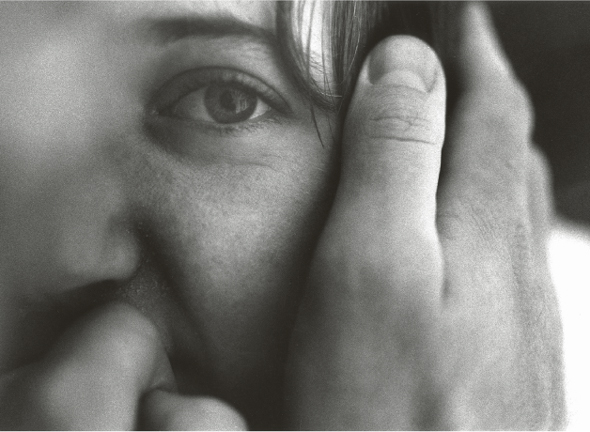

It’s Easier with People You Know

You can easily approach acquaintances, and even touch or photograph them in more intimate situations. The blunt crop of the next portrait (figure 13–6) is what makes it powerful: Only one eye is clearly seen, while the left side of the face remains fully blurred. The nose emerging from the blur can barely be recognized, but the eye is razor sharp and the hand on the right side leads once again to blurriness. The image has a certain poetry: The eye reveals some fearfulness and melancholy and the woman places her hand on her mouth while the other hand touches her face. What kind of story is hidden in this small detail? Is the hand comforting the face? Maybe the photo is telling the story of a romance. The photo does not give us a clear answer and that is precisely what makes photography so fascinating—that it is open to many interpretations. Even if the story behind the image remains mysterious, it is nonetheless emotional.

The photo was taken with a fully opened analog camera and a light-sensitive 50 mm lens on a very sensitive film.