Chapter THREE

The Terrible

Profit Amid Depression

In the 1930s, the number of radio sets in use continued to increase. In 1930 an estimated 40% of America’s homes had radios. Considering the state of the economy, that was a large number. Listeners heard more and more vaudeville-type shows. As the Depression proved the beginning of the end for vaudeville theaters, or houses, as they were called, the performers tried to re-create their acts on radio, some successfully breaking into network radio and others settling for a job—any job—at a local station. Throughout this decade, many future entertainment stars got their start working for peanuts on small radio stations.

Successful network programs were given long-term renewals, establishing a star system that continues today. Amos ’n’ Andy, for example, which had gone on the network only the year before, in 1929, contracted for five years, making its creators and stars, Charles Correll and Freeman Gosden, the highest-paid radio entertainers up to that time. As with other stars whose shows had one sponsor, their contract was with their sponsor, Pepsodent toothpaste, which in turn signed with NBC as the show’s exclusive agent.

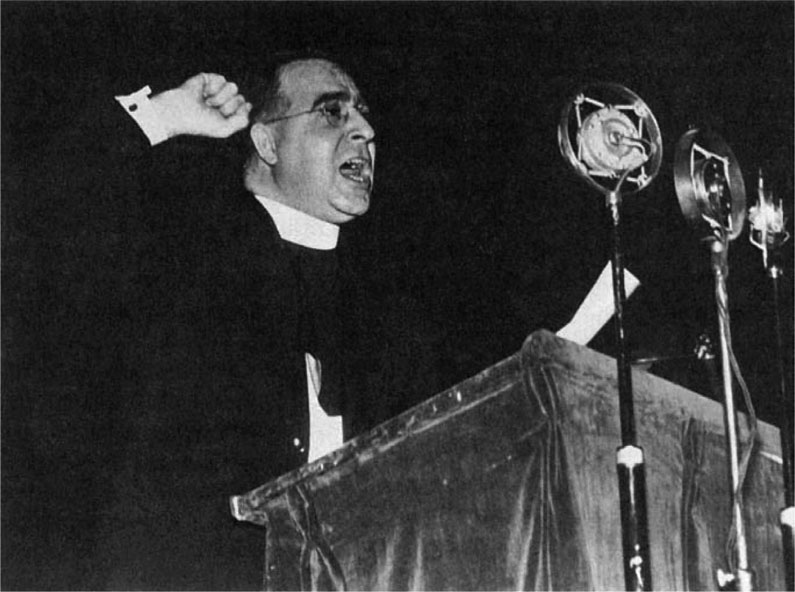

But perhaps the most significant event in programming was the introduction of regularly scheduled hard-news broadcasts on the NBC Blue Network with the reporter-commentator Lowell Thomas, who would remain a leading newscaster, first on radio, and then on television, for a half century. Another commentator who successfully used the power of the media to affect people’s minds and emotions made his debut in 1930. Father Charles E. Coughlin exploited the airwaves for the next decade with a right-wing, anti-Semitic message of “social justice” that influenced millions of economically frustrated Americans. His audience was estimated to be as high as 45 million. One type of program, however, was at least temporarily restrained. In a landmark action, the FRC refused to renew the license of Kansas station KFKB, whose owner, Dr. John R. Brinkley, had used the station for medical charlatanism. As radio audiences in general grew, the Crossley research organization, established the previous year, began extensive ratings services.

Fig 3.1 Publications such as this 1930 issue of Radio News kept radio enthusiasts well informed.

Those who were concerned about the increasing demise of educational stations and who believed that radio should be principally an educational/informational medium formed two organizations to promote educational radio: (1) the National Committee on Education by Radio and (2) the National Advisory Council on Radio in Education. Their efforts were supported by an unlikely commercial ally, newspaper publishers, who were increasingly concerned with the draining off of newspaper advertising dollars into the entertainment programs of radio. CBS introduced its own educational program designed for the classroom, the American School of the Air.

Fig 3.2 Father Coughlin’s political preaching stirred a broad range of emotions and attracted large audiences.

Courtesy Anthony Slide.

One form of education through radio, although often lacking distinction, was that of programs for children, mostly on local stations. These shows consisted mostly of performers playing music for children and telling children’s stories. A feature of many of these programs was the birthday greeting (usually sent in, of course, by a doting parent or grandparent). What a thrill for a child to wait expectantly by the radio on a birthday morning to hear his or her name announced on this magic medium for all the world to hear!

In a preview of the “media diversity” approach that would be taken by the FCC some years later, the U.S. government filed an antitrust suit against the longtime “patent allies” headed by RCA and including GE, AT&T, and Westinghouse. These companies’ control of some 3,800 patents gave them almost monopolistic control of the production, transmission, and receiving equipment of radio—and of motion pictures and phonograph records as well—and put them in a position to impose their policies and beliefs on the content of the medium. While RCA was defending itself on this front, it took a step on another that would result in its even greater growth as a radio giant: David Sarnoff was appointed president of NBC.

On the technical side, Edwin Armstrong progressed with his idea for an FM transmission system, determining that FM needed a wider bandwidth than AM to avoid interference, and he applied for the first four patents that were to be the bases for FM radio. AM wasn’t worried about FM yet, however. But it did begin to worry about TV, and CBS applied for a television license, not because it expected to begin television programming in the near future but to protect its future interests and, as the New York Times stated, “to be prepared for competition when radio is supplemented by visual broadcasting.” Technical advances in television included a demonstration by NBC of what it called a Flying Spot Scanner, a refinement of the Nipkow 1884 disk, that separated images into transmittable segments. The NBC demonstration used the cartoon character Felix the Cat as a subject on its 60-line transmission and, although the picture was quite fuzzy, it was discernible.

Fig 3.3 Expensive and elegant cabinets housed receivers so as to make them a more integral part of the parlor setting. This 1930s magazine advertisement promotes the popular RCA Radiola 62 cabinet model.

Those less optimistic about television included the magazine Radio World, which conceded that television was an interesting subject for experiment but still had a long way to go: “The more the ordinary man discovers about the halting advance of television, the more he is urged to be satisfied with radio as it is and to lay in his radio supplies for the winter.”

Radios in Cars

Although automobile radios were available by 1927, it’s hard to fathom why anyone would’ve wanted one–when the engine was running you could barely hear anything but static. The electrical energy generated by the motor produced intolerable interference. (There were other obstacles that were easier to overcome, such as making a radio small enough to fit yet sturdy enough to take the abuse of rough roads.) The static problem was solved by 1930 through a fortuitous meeting of Paul Galvin and Bill Lear. Galvin had a company that manufactured battery eliminators, a product that allowed battery-powered radios to operate on household current. Located in the same Chicago building was Lear’s radio parts business. The two united to solve the problem and chose to demonstrate it at a radio manufacturers’ gathering in Atlantic City, but because they didn’t have the fee for admission, they had to display their product outside the convention hall. The success of a functional car radio led to the formation of one of the communication technology giants, Motorola. Lear became one of the legendary inventors of the last century with, most notably, the Learjet, the first private jet aircraft, and the often ridiculed eight-track audiotape player.

1931

Both the business and the programming of radio grew in 1931. There were more commercials, more giveaway contests, more gimmicks for selling products and services, and more promotional schemes for the stations themselves. As more money became available to hire name performers, more stars from the theater, concert halls, and nightclubs tried the new medium. Even Hollywood personalities, who by and large had snubbed radio, became aware of the medium’s power to create and sustain national recognition.

Radio stations began using increasingly flexible portable equipment for what were called “stunts”—reporting live from caves, on mountainsides, even during parachute jumps. These first remotes were made possible by the assignment of shortwave frequencies by the FRC for short-distance use where wire facilities were not available.

While newspapers continued to battle the inroads of radio, one representative of the print medium joined the aural medium. Time magazine produced on CBS The March of Time, a weekly dramatization of the key news events of the previous seven days. The program caught on immediately, becoming a favorite much like 60 Minutes has in more recent years. And the print medium spawned another electronic media magazine, one that was to become the most important journal of the business of broadcasting: Broadcasting. This industry publication provided the most comprehensive coverage of the radio medium (and later of TV and cable), especially in the areas of regulation, business, technology, and programming. The business of broadcasting was to take a huge jump in another direction, too: under way was the development of Rockefeller Center in New York City, which would become known as the home of Radio City, NBC’s headquarters. But RCA was premature with an invention of one of its other divisions, the Victor Talking Machine Company. In 1931 Victor produced the first 33⅓ plastic record; however, unsatisfactory quality, lack of record players, and poor marketing delayed its serious entry into the home until after World War II.

International programming increased. Foreign leaders who had been read about in newspapers and seen in movie newsreels that were sometimes weeks out of date were now heard live on radio. One of the great playwrights of all time, George Bernard Shaw; the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini; the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi; and Pope Pius XI were among those who reached the American people from overseas by radio in 1931. The Pope’s February 12 address on world peace was the occasion for a classic network goof. The speech was being carried by NBC’s Blue Network. On NBC’s Red Network at the same time was a remote light program, The Shell Ship of Joy. When the time came for the announcer, Cecil Underwood, to give the closing network announcement for The Shell Ship of Joy, he flipped the switch for the Blue instead of the Red Network and cut into the Pope’s presentation with the words, “This past hour of fun and nonsense has come to you over KPO, San Francisco.”

Fig 3.4 A 1931 Atwater Kent (superheterodyne) “cathedral” model table receiver.

The organizations that had been formed the year before to promote educational broadcasting found a champion in Representative Simeon D. Fess of Ohio, who unsuccessfully introduced a bill in Congress that would have reserved 15% of the radio frequencies for educational stations. Of the 129 educational stations that had been operating in 1925, only 51 were still on the air. It would be some years before such reservations were actually approved. In an unrelated action involving the government, AT&T, in an effort to extricate itself from the Justice Department’s antitrust suit, withdrew from the patent-allies group.

Fifteen experimental television stations were on the air in 1931. But TV receivers were extremely expensive, and with the opposition of the radio-oriented networks it was not possible to subsidize the necessary programming to make the stations viable. Still, they hung on as best as they could, in anticipation of a rosy future. CBS was optimistic enough to begin TV broadcasting that year.

1932

The Great Depression had hit hard by 1932, and the principal escape for millions of homeless, hungry, and ill Americans—and for millions more on the edge of poverty—was radio. Losing oneself for a half hour, an hour, or an evening in jokes, laughter, and song was a welcome alternative to total despair. Tuning in to daytime dramas, in which the characters were sometimes worse off than listeners and had at least as many troubles, made life a bit more bearable. Comedians dominated radio. Eddie Cantor, star of musical comedy and vaudeville, topped the Crossley ratings with his weekly program in 1932. Another vaudevillian, Fred Allen, entered radio in 1932, offering a literate, dry sense of humor that kept his program on the air in the top 10 until it was outrated in its time slot by a quiz show, Stop the Music, in 1949. It was the beginning of the age of Jack Benny, Burns and Allen, Fibber McGee and Molly, Ed Wynn, Rudy Vallee, Al Jolson, and others who kept America laughing and singing for a few hours each week, not only through the Depression but for decades to come.

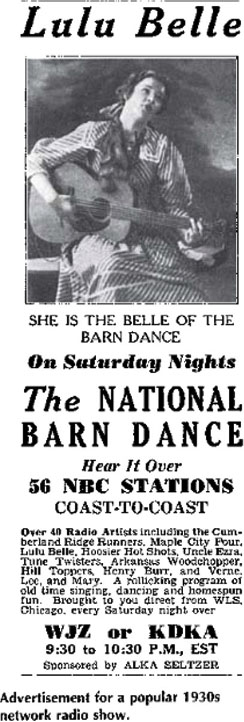

The national audience was now large enough to prompt advertisers to sponsor entertainment for targeted audiences; one such show that began its network run during the 1932–1933 season was the National Barn Dance. Another type of program that was to become highly popular, the morning talk show, also made its debut that season, Don McNeill’s Breakfast Club.

Other types of programs increased, too: soap operas, drama, mysteries, Westerns, adventure, and crime. One of the most listened-to soap operas of the time was One Man’s Family, which lasted for 28 years. Other new and growing program types included shows for women, with formats that emphasized cooking and beauty tips and that predominated until the women’s movement in the 1970s prompted less sexist and more meaningful content in so-called “women’s programs.” Another successful format was radio’s version of the gossip column, which made Walter Winchell a leading radio personality for many years.

Music continued to be the principal programming of radio, and an announcer at KFWB in Los Angeles introduced a new format that would become the standard for all radio pop music shows. Al Jarvis played records with commentary on his Make Believe Ballroom, a title and format that would be even more popularized a few years later when Martin Block did the same kind of show on WNEW in New York. Al Jarvis and Martin Block are generally considered the first radio disc jockeys, or deejays.

Radio news opened new vistas for radio journalists and for listeners. Live coverage of special events, such as the 1932 Republican and Democratic National Conventions, became commonplace. One of the most publicized crimes of the century, the kidnapping of the baby of America’s most popular hero, Charles Lindbergh, spurred extensive radio coverage, one of the first national “media events.” Radio carried not only news about the kidnapping but broadcast appeals to the kidnappers. Reporting the case daily to an eager public made the commentator Boake Carter one of the first media news stars. A few years later, in 1935, the same case—this time the execution of Bruno Hauptmann, who was convicted of kidnapping and murdering the Lindbergh baby—made a media star of another commentator, Gabriel Heatter, whose ad-libbing for almost an hour during a delay while reporting the execution held the rapt attention of millions of listeners.

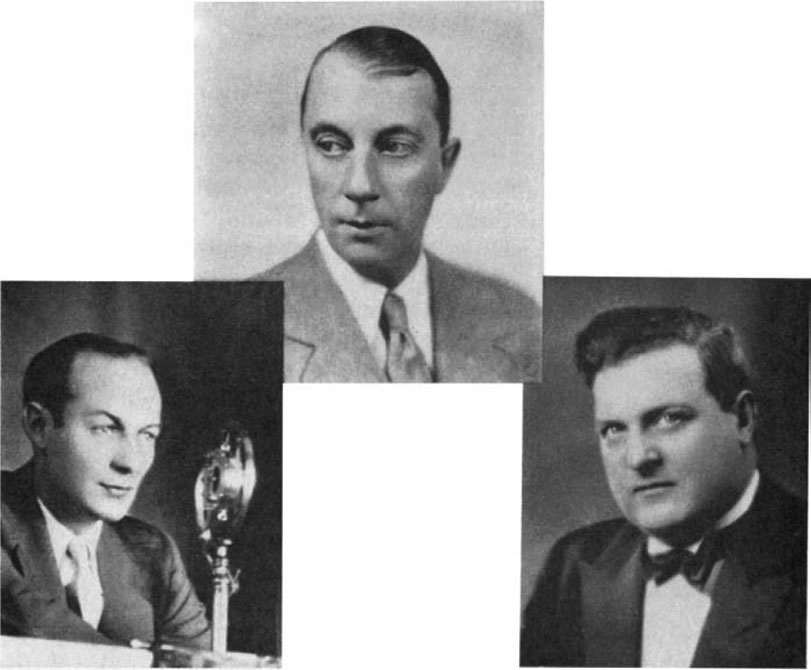

Fig 3.5 Among the earliest radio performers who became stars of the medium were Ted Husing (left), Graham McNamee (center), and Milton Cross (right).

As radio news grew, newspapers tried harder to muzzle this competition and pressured United Press (UP), a news service, to break its contract with CBS to provide 1932 election returns. The Associated Press (AP), UP’s rival, agreed to provide election results to CBS and NBC free of charge. To counter this action, UP reversed itself on election night and offered its service, as did another competitor, the International News Service (INS). By the time the newspaper “extras” came out the next day, everyone with a radio set already knew what had happened. This was the beginning of the end of newspapers’ dominance as news purveyors.

The business of radio took turns both toward and away from monopoly. The patent-allies split, RCA, GE, and Westinghouse separating by consent decree in order for the Department of Justice to drop its antitrust suit. That split gave stations more freedom. On the other hand, NBC became a wholly owned subsidiary of RCA, and William Paley, head of CBS, bought out the Paramount movie company’s holdings in the company. These events gave RCA and CBS more control.

On the television front, NBC started broadcasting from its station in the Empire State Building, the world’s tallest, constructed the previous year. In 1932, 38 experimental TV stations were on the air in the United States.

Fig 3.6 Lowell Thomas spent nearly a half century before the network microphone.

Fig 3.7 Hilmar Baukhage began his daily news broadcasts on NBC Blue in 1932. Later in the decade he would report from Europe on the rise of Hitler.

Courtesy Irving Fang.

Fig 3.8 H. V. Kaltenborn, the first radio commentator in the United States.

Courtesy Irving Fang.

The Trigger of the Press-Radio War

It reads like a plot from a soap opera, but what sparked the decisive denouement of the Press–Radio War actually occurred, and the players were not some fictional characters but large corporate entities. During the early 1930s, as the Depression deepened, tensions rose among newspapers, the wire services, and radio. By 1932 the major newspaper cartel had persuaded the wire services not to furnish news reports to radio stations. Before the 1932 Presidential election, the United Press brokered a secret deal to provide CBS with the election night returns. But word of the deal leaked out, and under pressure from a council of newspaper owners who threatened to cancel their service, the UP voided the agreement. The Associated Press also heard of the deal, but not, so they claimed, of the cancellation and made its own arrangement to supply NBC with election night returns. And so, on election night, only NBC had the most up-to-date results while its major competitor, CBS, was left far behind. Now everyone was fuming—newspapers, of course; UP, which had sacrificed much needed revenue by breaking its contract with CBS; and CBS itself, which lost to NBC listeners who sought the latest results.

1933

While the stage was set for future war in Europe, a media war broke out in the United States when the newspapers finally took drastic action to curb the growth of radio and the siphoning off of its advertising revenue. In 1933 the “Press–Radio War,” as it has been called, reached the fighting stage when the newspapers succeeded in convincing the three major news services—UP, INS, and AP—to continue offering their services only to those radio stations owned by newspaper members of the given wire service. Some years earlier, in 1928, the wire services had begun providing two reports daily to radio stations. The newspapers weren’t too worried then, but by 1933 the networks and many stations were carrying daily 15-minute news reports. Most newspapers had already stopped printing radio schedules unless stations paid them to do so. The newspapers even convinced Congress to bar radio reporters from press galleries. CBS already had a large news department and set up its own news service. But the pressures were too great, and radio capitulated at the Biltmore Conference (named after the New York hotel in which it was held).

The two major networks, CBS and NBC, agreed to refrain from gathering their own news; they would carry not “hard news” but only commentary, which would be broadcast just twice daily in five-minute segments, unsponsored, and provided by the wire services through a Press-Radio Bureau, to be established the following year. Many independent stations and even affiliates rebelled at these restrictions, however, and began to set up their own news-gathering services. Only about half the stations subscribed to the Press-Radio Bureau. It was clear that the newspapers’ strategy had not worked, and in less than a year the Biltmore agreement was undone. Although the wire services then began to provide full reports to radio again, radio realized the need for its own news-gathering services, with materials prepared specifically for radio delivery. Out of this need came the growth of network news operations, with CBS taking an early lead.

Radio news became more and more important to the American public. The new U.S. President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, inaugurated on March 4, 1933, began to take immediate, dramatic steps to cope with the economic disaster. On March 12, Roosevelt began the first of a series of radio talks to the nation that over the years would become known as FDR’s “fireside chats.” Roosevelt demonstrated the political power of radio; so effective were his fireside chats that for the first time the people felt they were in direct contact with their President, sharing problems and ideas and participating in the administration of their country. Roosevelt’s use of radio, including some 28 (estimates vary) fireside chats during his tenure in the White House, was an important factor in his election to an unprecedented four terms.

The political power of radio was not limited to the United States. The dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini, was using radio at least as effectively and was once quoted as saying that had it not been for radio, he would not have been able to gain the control over the Italian people that he did. And in its last democratic election prior to the post–Berlin Wall unification of East and West Germany in 1990, Germany elected its Nazi party leader, Adolf Hitler, as its chancellor. Hitler also used the media with great effect. The rising tide of fascism in Europe and the actions of Germany’s Hitler and Italy’s Mussolini fed U.S. radio stations with news of increasing critical interest to the U.S. public. At the same time, the public wanted to escape from the realities that kept coming closer from over the horizon, and radio entertainment provided that escape.

Fig 3.9 FDR was a frequent presence on radio in the 1930s.

Courtesy David Sarnoff Library.

Networks grew. NBC now owned 10 stations outright and was increasing its number of affiliates, as was CBS. Radio revenue decreased as the Depression deepened. Because people didn’t have money to buy products, less advertising money was available—and anyway, why advertise if people had no money to buy? It was an oppressive circle. Nevertheless, radio was doing better financially than most other businesses in the country. Among other approaches, stations offered discounts to those sponsors who paid their bills within given time periods. During this time one advertising practice was established that still exists today: The Twentieth Amendment—Prohibition—was repealed in 1933 and, although alcohol commercials were legal, CBS set a precedent by carrying only beer and wine ads and refusing those for hard liquor.

Programs and their stars became even more closely identified with the products that sponsored them. For example, Jack Benny’s program “hello” during his longtime sponsorship by Jell-O dessert was “Jell-O again, this is Jack Benny.” The year 1933 was a landmark programming year if only for one program that made its debut: The Lone Ranger. Not only did it become one of the favorite programs of all time, but it had tens of millions of people throughout the world humming and whistling classical music—its theme from Rossini’s William Tell Overture.

The Biltmore Agreement

The settlement reached after two days of what was described as the “smoke and hate filled rooms in the Hotel Biltmore” that ended the Press–Radio War appeared to be a resounding victory for newspapers. The terms imposed severe restrictions on radio just as the nation was thirsting for news. The agreement stipulated that radio was to be limited to 30-word reports, sustaining (unsponsored) to be broadcast only twice a day, one after 9:30 a.m., the other after 9:00 p.m., times selected so as to ensure that these reports would air well after the morning and evening papers had been distributed. Radio could only cover items that were at least 12 hours old, with details supplied by the Press-Radio News Service, a newspaper-created entity. However, the agreement placed no restriction, save for the 12-hour embargo, on any form of news that was labeled “backgrounding” (news analysis) or commentary. A commentator could “interpret” events, offering context and meaning, something that listeners’ desperately craved. And most significantly, backgrounding could be sponsored, obviously an enormous economic enticement for radio. Almost immediately, analysts flourished on the airwaves, and to demonstrate that these commentators were not reporting “news,” they were usually budgeted under the station’s Entertainment Division.

1934

The FCC, which continues to be the federal regulatory agency responsible for communications, was established in 1934. The Radio Act of 1927 did not give the FRC jurisdiction over telegraph and telephone carriers. Supervision of nonradio operations was divided among a number of federal offices, including the Post Office Department, the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the Department of State. In 1933 President Roosevelt directed an interagency committee to study the problem of government regulation of electronic communications. The committee recommended that a single agency be established to regulate all interstate and foreign communications by wire and radio, including broadcasting, telephone, and telegraph, with provisions for inclusion of newly developing media, such as television, that might fall into these categories. Congress thus enacted the Communications Act of 1934, which created the FCC. The FCC began operations on July 11, 1934, as an independent agency composed of seven commissioners appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate.

Section I of the Communications Act of 1934 describes the purposes of the act in creating the FCC:

regulating interstate and foreign commerce by wire and radio so as to make available … to all the people of the United States a rapid, efficient, nationwide, and worldwide wire and radio communication service … for the purpose of the national defense … promoting safety of life and property through the use of wire and radio communication … by centralizing authority [in the] Federal Communications Commission.

Various other sections and titles of the act dealt with the FCC’s jurisdiction, definitions of the various services the FCC might regulate, FCC administrative procedures, and penalties for violations of the act. Over the years, the act has been amended many times, with a number of appendices added.

Whereas the industry had virtually begged for the Radio Act of 1927, now that it was a well-established, money-making business, it didn’t like the idea of more extensive regulation. Led by its association, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), the industry generally opposed creation of the FCC, a new, more powerful federal communications office. Broadcasters were especially concerned with the FCC’s renewal authority and the manner in which the Commission might require their compliance with the “public interest, convenience, or necessity” provision of the Communications Act.

More than 60% of the country’s homes had radios in 1934, and radio sets could be found in more than 1.5 million automobiles. Some people even set up “radio rooms” in their homes; these persons were, of course, those who had large enough houses and money, not a very prevalent situation during the Terrible Thirties. But radio was so thoroughly established as a lifestyle necessity, even during the Depression, that the New Republic magazine wrote, “Radio is here! This is the art that encompasses all of the arts, the center of interest of the modern home, the culture font of today.” Even members of the poorest household did with radio what is done with television today: At the beginning of each week, they looked at the radio schedule in a newspaper or magazine to decide what they should tune in to during the next seven days.

Fig 3.10 Car radios were becoming standard equipment in the 1930s, as this magazine advertisement shows.

One area that continued to get short shrift, however, was educational radio. The National Advisory Council on Radio in Education and the National Committee on Education by Radio were unsuccessful in gathering sufficient public or political support for an amendment to the Communications Act that would have reserved 25% of the frequencies for educational use. The Association of College and University Broadcasting Stations, a group that had been in existence since 1925, when many college stations were going on the air, reorganized itself into the National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB). This organization eventually became the principal membership and lobbying group for educational radio and television and some years later was largely responsible for the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. The NAEB continued in existence until 1981, when the strengths of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), and National Public Radio (NPR) made NAEB’s organizational approach and services no longer necessary.

LAYNE BEATY FORMER NETWORK AGRICULTURAL REPORTER

It may be a coincidence that the first use of the term broadcast was agricultural, referring to the sowing of seeds. It is nonetheless fitting because in the early days of radio, when rural people lived in varying conditions of isolation, radio became a link to the outside world and a live-in companion for farmers and their families.

Those first two radio stations, KDKA Pittsburgh and WHA Madison, emphasized such services. Stations justified the use of their assigned frequencies and power by their broadcasts of market prices, updated weather forecasts, information on better farming practices, government regulations, and commercials adapted for far-flung rural listeners. In my long career, those years spent broadcasting agricultural programs were undoubtedly the most rewarding in terms of public acceptance. My listeners included not only country folk but urban professionals as well, and one network program (the old NBC Farm and Home Hour) drew mail regularly from the Wall Street area. On the air, I tried to be warm and friendly with some natural humor, not contrived, too corny, or suggestive—no inside jokes. I made as many personal appearances as possible, and this helped build listenership and goodwill for the station. Entertainment (music, etc.) and long features, early staples on farm programs before good roads and television, have disappeared, making way for shorter, more concise reports aimed at helping farmers and ranchers (and sponsors) turn a profit.

Fig 3.11 In 1947, when the United States was cooperating with Mexico to stop the spread of the costly hoof-and-mouth disease of livestock by killing and burying thousands of head of cattle in the quarantined areas of central Mexico, Layne Beaty, then the farm editor of WBAP in Fort Worth, Texas, went to the scene with his new wire recorder. Here he is pictured interviewing a top Mexican government veterinarian in Mexico City.

Courtesy Layne Beaty.

There was enough business for a fourth radio network, in addition to NBC’s Blue and Red and CBS, and four stations (WGN, Chicago; WOR, Newark; WLW, Cincinnati; and WXYZ, Detroit) joined forces as the Quality Network to boost their individual advertising revenues, although without a centralized administration. This entity shortly became the Mutual Broadcasting System, which continues today, though it, unlike the other networks, did not add television to its operations. One of the network’s stations, WLW, obtained special permission to operate with an experimental power of 500,000 watts in a bid to become, as it called itself, the “Nation’s Station”—a phenomenon that didn’t truly come to pass until decades later, with Ted Turner’s nationwide distribution of his Atlanta television station, WTBS, on cable. WLW soon became a favorite station in much of the Midwest and in the evening in other parts of the country, with substantial income from regional and national advertising. This situation continued until 1939, when the FCC, under pressure from other stations to give them the same privilege, revoked WLW’s 500 kW authorization except from 1:00 to 6:00 a.m., which had been its original hours under the experimental grant. In 1942, with restrictions on all communications due to the war, WLW was forced to go back to 50 kW full time, and this has remained the highest power for all AM stations since. (FM stations do not have this power limit.)

As audiences grew, so did advertising and, in turn, rating systems. A competitor to Crosley, Clark Hooper, made phone surveys of what the respondents were listening to at the time of the call and claimed that his method was more accurate than the Crosley next-day recall approach. Soon the Hooper ratings became dominant in the field.

The technical progress of both the old and the upcoming media continued. In 1933 Edwin Armstrong received patents he had filed as long as four years earlier for the frequency modulator limiter, the basis of FM radio, and in early 1934 he demonstrated FM for his old friend, NBC’s David Sarnoff. Unfortunately for Armstrong and Sarnoff’s friendship—and for FM—RCA and NBC were protective of AM growth and, if anything, preferred to promote TV rather than have a direct competitor like FM in the wings as the next new medium. After a year of experiments in the RCA quarters at the Empire State Building, Armstrong was told to leave. Although he gave a public demonstration of FM to the Institute of Radio Engineers in November 1934, and in 1935 the FCC allocated some channels to FM, these channels were largely unsuitable and in scattered places on the spectrum; FM would thus remain in abeyance for some years more. Another blow to Armstrong was the Supreme Court’s 1934 decision awarding to Lee de Forest the rights to the regenerative, or feedback, circuit, the key to modern radio for which both had applied for patents in 1914. RCA had a licensing agreement with de Forest and backed him with its legal resources; however, it is now generally believed that Armstrong should have got the credit for the invention.

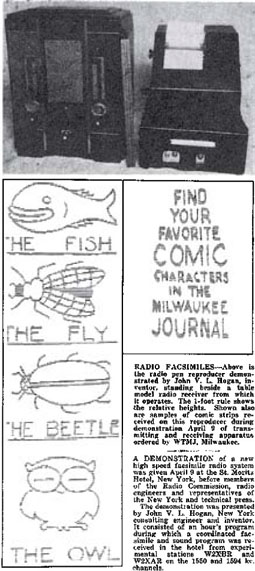

An interesting experiment that presaged the future was a 1934 demonstration of facsimile transmission through radio by its inventor, John V. L. Hogan. It was called a radio pen reproducer.

1935

Although still not close to the 99% penetration we know today, more than two out of every three homes had radios in 1935. Not only were the four national networks thriving, but some 20 regional networks were in operation. Independent stations were having a tough time competing with network affiliates, and more and more stations sought to affiliate, despite the long-term contracts and strong control demanded by the networks. As the economy began to show subtle signs of recovery, advertising grew, with ad agencies placing more than 75% of all radio commercials and concomitantly exercising even more power over programming.

Fig 3.12 This article on the “fax machine” appeared in the April 15, 1934, issue of Broadcasting magazine. Popular application of fax technology was decades away.

Courtesy Broadcasting.

Comedians continued as the public’s favorite entertainers, with such performers as Jack Benny, Eddie Cantor, Ed Wynn, Burns and Allen, Joe Penner, and Fred Allen becoming household names. The year 1935 saw the debut on radio of a musical comedy performer who overcame his first negative impression of radio to become a star of it and, later, of television and movies for the remainder of the century—Bob Hope. The Big Band era was enhanced by radio, especially through such programs as Your Hit Parade, which featured the top songs of the week played and sung by top bands and singers; teenage (and even older) dance parties were planned around the Saturday-night broadcasts of Your Hit Parade. Another of the most popular shows of all time, one that continues to spawn imitators even today, moved from a local New York station to the NBC Red Network in 1935: Major Bowes and His Original Amateur Hour. The audience called or wrote in their votes for the best amateur performer of the night, urged on by Major Bowes: “The wheel of fortune spins, round and round she goes, and where she stops nobody knows.” Some of the greatest popular and classical stars in America got their start on the Amateur Hour, including, in its first year, a skinny kid from New Jersey named Frank Sinatra.

Children found radio a companion for all reasons, from rapt concentration to background sound for doing homework (although perhaps not so distracting for the latter as TV is today). In addition to preschool programs in the morning and early afternoon, networks and stations offered adventure stories beginning at 3:00 p.m., as soon as the school day ended, up to and past 6:00 p.m., the supper hour. Those old enough to remember the rush to the radio after school through the 1930s probably recall the musical themes, the commercials, and the announcers’ introductions, as well as characters and plots of such shows as Jack Armstrong—The All-American Boy, Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, Buck Rogers—In the 25th Century, Chandu the Magician, and Bobby Benson, as well as the perennial sound of “Hi-ho, Silver, awaaay” of The Lone Ranger. Programs generally reinforced, perhaps unintentionally, the racism of the country, rarely presenting racial minorities and, when they did so, mostly in stereotyped roles. The sexism one finds in some children’s television shows today was present then: There were virtually no females in the radio adventure serials, except in secondary roles as helpmates to the male characters. And just as there is with television today, there was concern over the content of children’s programs, principally violence. In fact, both CBS and NBC adopted guidelines designed to reduce violence and promote such virtues as clean living, fair play, moral courage, and mutual respect. We know that radio, like television, has had a great impact on the thinking and behavior of youth. Many critics questioned how effectively the networks implemented their early policies regarding children’s programming.

Fig 3.13 Advertisement for a popular 1930s network radio show.

Fig 3.14 The list of popular performers of radio’s golden age included Bob Hope, Fibber McGee and Molly (Jim and Marion Jordon), and Jimmy Durante.

Courtesy WTIC.

Fig 3.15 Excerpt from a November 20, 1935, radio magazine showing the evening program schedule, top songs aired, and advertisement for a mystery feature.

Although attempts were made to address the area of children’s programming, radio news was beginning to move closer to legitimacy. In 1935 the UP began sending newspaper-style stories directly to broadcast stations. The following year UP took the next step: It created a totally separate wire service just for radio stations, with stories written especially for the audio, rather than the print, medium. Over at CBS, unbeknownst to anyone at that time, an era began as the reporter who would become broadcasting’s most famous news and documentary personality joined the network. His name was Edward R. Murrow.

1936

As part of its reorientation of broadcast regulation, the FCC supported the repeal of the Davis Amendment to the Radio Act of 1927, which had provided for equal growth of radio stations in the various geographic sections of the country through allocations by zones and states. Now the FCC could license stations on the basis of population and demand, permitting the medium to grow as the marketplace required. The FCC also began what was to become the networks’ and group station owners’ greatest concern: inquiry into monopoly practices and, to start with, the ownership of more than one station in the same community.

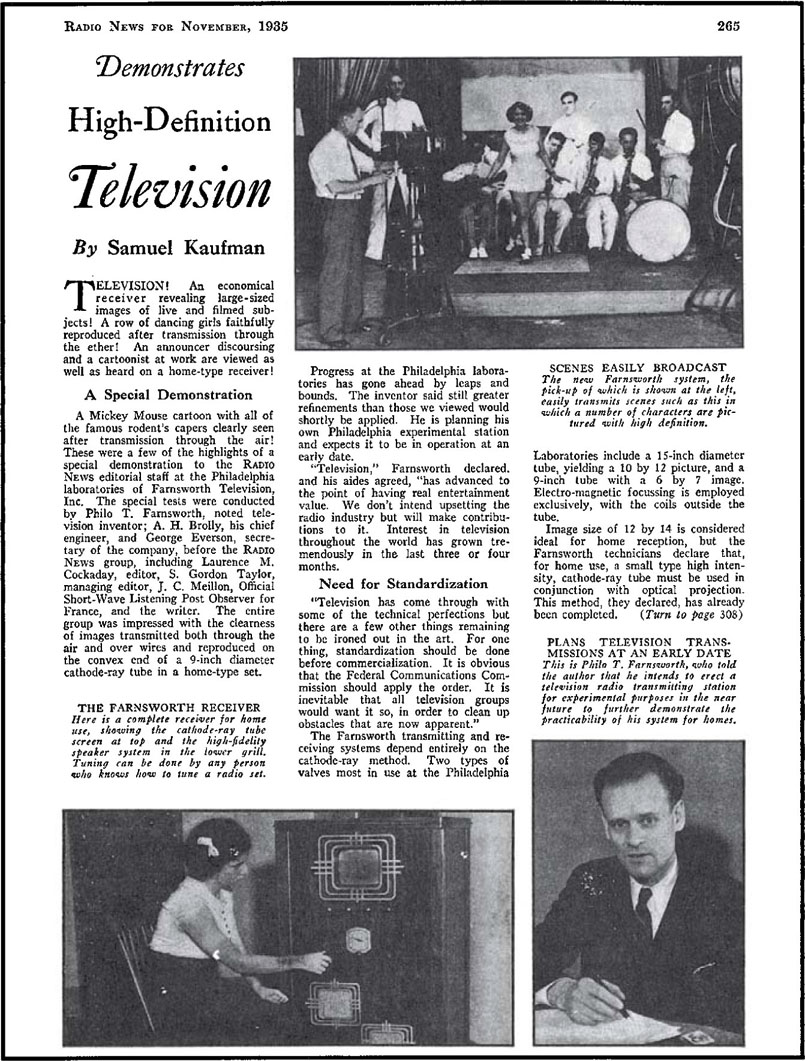

Fig 3.16 High-definition television (HDTV) was on the minds of broadcast technologists from the start, as this 1935 magazine article shows.

Fig 3.17 A radio receiver as end table. The idea was to enhance the utilitarian nature of the home living-room receiver.

While the politics between the government and the broadcasting industry were intensifying, so was the use of radio by politicians. “Sound bites” designed to convince citizens to vote on the basis of image rather than substance—the practice of television and radio in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s—had not yet been developed. But the importance of media in reaching the public was recognized sufficiently that more than $2 million—a large sum in the Depression-ridden 1930s—was spent on radio political campaigns in 1936. The Republican Party understood the impact of radio and combined entertainment and rhetoric in a program series entitled Liberty at the Crossroads, which presented issues from the Republican point of view through dramatic sketches.

Fig 3.18 Kate Smith was one of broadcasting’s beloved entertainers.

Politics on radio created controversy. The Depression, having created millions more poor, prompted the organization of political movements designed to redress the imbalance of economic power and provide opportunities for the economically deprived and for racial and other minorities. The Communist Party of the United States reached a peak of membership and influence in the mid-1930s, and in 1936 its head, Earl Browder, made a speech on CBS. All hell broke loose. Right-wing organizations picketed and protested, a number of affiliates refused to carry the program, and the conservative Hearst press even called for the government to take over broadcasting, to prevent what the newspaper chain considered subversive use of the airways. They needn’t have worried. The government didn’t take over the radio system, and to this very day the broadcast media, operating as big business and dependent on advertising from big business, have rarely given airtime to controversial, especially left-wing, political opinions.

Right-wing radical opinion was carried, however, and so effective were some of its radio commentators that one of them, Father Coughlin—described earlier and considered by many an antidemocracy, profascist demagogue—became so popular through his use of radio that he was able to form a third political party for the 1936 Presidential election. As turmoil grew in Europe, radio carried increasing numbers of reports and programs from overseas, in fact doubling the number from the year before. Of great interest to many Americans was the coverage of the 1936 Olympic Games from Berlin.

The most important contribution to the art of the sound medium, though, was in another format. In 1936 CBS began its Columbia Workshop series, which introduced some of the finest writers and highest-quality experimental dramas and documentaries that broadcasting would ever know. Writers for the series included Norman Corwin, Archibald MacLeish, Stephen Vincent Benét, James Thurber, and Dorothy Parker.

Fig 3.19 The popular CBS radio comedian Ed Wynn on Texaco Star Theater in 1936.

Vladimir Zworykin and Philo Farnsworth continued to improve television in the United States with their electronic scanning systems. The two inventors were locked in court battles to determine whose patent rights were paramount. RCA invested $1 million—a huge sum in the 1930s—in field tests of television. A coaxial cable for TV transmission was installed between New York and Philadelphia. In the meantime, however, England moved ahead, and in 1936, with the opening of a British Broadcasting Company (BBC) television studio in London, became the first country in the world to broadcast a regular TV schedule to the public.

1937

The Golden Age of Radio clearly had arrived by 1937. NBC and CBS competed for stage and movie stars to appear in their radio plays. One of the all-time classics, The Fall of the City, an allegory on the impending war in Europe, was broadcast on CBS. Its author, Archibald MacLeish, showed that radio could be a medium for poets. Arch Oboler’s Lights Out, far more chilling than the already long-running The Shadow, made its debut on NBC. CBS hired a young producer-director-actor named Orson Welles to present the new Mercury Theatre series. Ultimately, hundreds of radio plays found their way into printed form and onto bookstore and library shelves around the country. In music, NBC established the NBC Symphony Orchestra, headed by the world-famed conductor Arturo Toscanini.

Fig 3.20 After enjoying great popularity on radio, Jack Benny became a hit on television.

ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, HERMAN WOUK, AND IRWIN SHAW

Many literary figures who traditionally invested their talents in book rather than broadcast form supplemented their pre–World War II incomes with assignments in radio:

Radio could not have been more perfectly adapted to the poet’s uses had he devised them himself.

—Archibald MacLeish

I was a staff writer on the Fred Allen show. He set the style, he did much of the writing, and he was the final editor of what I and other writers contributed.

—Herman Wouk

Unfortunately, the only radio writing I did was soap operas, which I fear had little if any literary merit, and which I abandoned as soon as I got a contract to do my first play in New York. However, I do think that there was a rich tradition of writing in the area of radio drama.

—Irwin Shaw

But not everything was peaceful in radio paradise. On The Chase and Sanborn Hour on NBC, the Hollywood sex symbol Mae West did what she was expected to: deliver her lines with sultry, sexual innuendo while playing the role of Eve in a sketch set in the Garden of Eden. So upset were some self-styled moral guardians of America that political pressure resulted in Mae West being blacklisted in radio for several years.

Broadcast news was given impetus by the accidental recording of the burning of the German dirigible, the Hindenburg, on its attempted landing at Lakehurst, New Jersey. Herb Morrison, a reporter for station WLS in Chicago, had brought a disc recording machine (there was no tape yet) to make a record of his report of the landing. There was no live coverage. Morrison’s record, with his now famous words, “This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world” and, amid his sobs, “Oh, the humanity,” was aired by all three networks the next day and prompted the increased use of recordings and live coverage at news events.

The networks were gearing up for the intensifying news events in Europe. CBS sent Ed Murrow there as a war correspondent. Although actual war had not yet broken out, Hitler’s Germany was already on the march for more lebensraum.

Fig 3.21 List of top radio advertisers during the 1930s.

As radio grew, with 80% of U.S. homes having at least one set and almost 5 million autos having radios, television moved closer to public realization. The FCC reserved a 6 megahertz (MHz) channel for television broadcasting. Philco was experimenting with a mobile unit in New York City and broadcast a 441-line image of a favorite comic strip character, Felix the Cat. Seventeen TV stations were in experimental operation throughout the country.

Fig 3.22 Newspaper account of audience reaction to the Mercury Theatre of the Air production of The War of the Worlds. Courtesy the New York Times.

1938

What some historians consider the greatest event in media programming history occurred on Halloween eve, October 30, 1938. At 8:00 p.m. Eastern time, a CBS announcer began the weekly program by saying, “The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre of the Air in The War of the Worlds, by H. G. Wells.” Three announcements during the program, produced by the then 21-year-old theatrical genius Orson Welles and a somewhat older theater guru, John Houseman, made it clear that it was a fictional drama. Welles’s closing narration stated that “The War of the Worlds has no further significance than the holiday offering it was intended to be … the Mercury Theatre’s own version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying ‘boo.’ … [I]f your doorbell rings and there’s nobody there, that was no Martian—it’s Halloween!” Nevertheless, the documentary nature of the presentation, with on-the-spot reporters describing the invasion from Mars, induced many listeners to think the Martian destruction of the earth was real. Tens of thousands of people panicked. Roads in areas of New Jersey and New York given as invasion sites in the play were clogged with fleeing people. Police and fire stations in the United States and Canada were deluged with calls from those seeking help and protection.

Fig 3.23 This 1938 RCA type 44-B ribbon velocity microphone became the premier radio microphone.

Courtesy Steel Collection.

Fig 3.24 KDKA’s pre–World War II control center.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

Fig 3.25 All manner of objects were assembled to create the sounds required for the production of radio scripts.

Courtesy WTIC.

Why did so many people panic? Reports from Europe had for some time indicated the likelihood of a German invasion of neighboring countries. Only a month earlier, a meeting of key powers at Munich had avoided the immediate outbreak of war. Everyone knew it was coming as the consequence of print and broadcast coverage. The public psyche was set for an “invasion.” So powerful was Welles’s production that in subsequent years, when it was repeated in translation in other countries, it continued to result in panics and, in some instances, in riots and mob actions against stations by a public incensed that it had been fooled. Although rebroadcasts of The War of the Worlds in subsequent decades did not scare a more sophisticated America (nor did it frighten one of this book’s authors, who heard the original when he was a youngster and, having read the Wells novel, accepted it as a good science fiction play), it remains one of radio’s classics and continues to be used in broadcasting studies and classrooms. Yet in this opening decade of the 21st century, productions of The War of the Worlds are still banned in a number of countries throughout the world.

A Social Scientist Looks at The War of the Worlds

The War of the Worlds is considered one of the most important broadcasts of all time. Serendipitously, scientists were presented a “natural experiment,” an empirical, real-world examination of what is now called media effects. Before this time the most recognized study in this arena, even with its methodological flaws, was a collection of reports known as the Payne Fund Studies that explored the effects of movies. A more rigorous study by psychologist Hadley Cantril, begun almost immediately after the airing of The War of the Worlds, revealed a number of factors that correlated with believing this program was real. Cantril found that a majority of those influenced failed to make “reality checks” (checking other stations or the newspaper radio schedule), missed the opening disclaimer (there were four such announcements during the show, but by the time of the second one, at the bottom of the hour, panic had set in), were highly suggestible and tended to believe everything they heard, or held to a more literal reading of the Bible, trusting this was the prophetic end-time. But Cantril concluded that the most important factor was critical ability associated with education, since vastly fewer high school graduates and even fewer college grads believed it was a real alien invasion.

Though The War of the Worlds was fiction, the developing events in Europe were not, and shortwave broadcasts kept the American public informed. Networks began regular world news roundups. Ed Murrow covered Germany’s annexation of Austria; another famed commentator, H. V. Kaltenborn, reported the attempts at the Munich meeting to avert war and also broadcast from the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War. In other programming, daytime soap operas, game shows, and audience participation programs gained in popularity, spurring increased advertising revenue. Although much broadcast music was on records, with music transcription services used by many stations, 64% of network programming was live. Writers and producers began to gain importance, and the person whom many critics regard as radio’s foremost writer, Norman Corwin—still writing and teaching as this is written—joined CBS.

Even the FCC got into the act and warned broadcasters not to air programs that might delude or deceive the public, as some claimed The War of the Worlds did. In other actions designed to protect the public interest, the FCC began requiring annual station financial reports (a requirement that lasted until the deregulation period of the 1980s), adopted rules governing political broadcasts, and expanded its inquiry into multiple-ownership situations, specifically into network practices and their relation to and control over affiliates. This study of chain broadcasting was to have great impact on the structure of broadcasting.

Edwin Armstrong’s invention looked like it was reaching fruition. He himself, having sold his extensive RCA stock, built his own FM station in Alpine, New Jersey—W2XMN, at 50 kW—which would go on the air the following year. The FCC reserved 25 FM channels in the 41–42 MHz band for noncommercial educational stations.

Fig 3.26 Sounds used in programs were generated live throughout radio’s early years.

Courtesy WTIC.

Television was gearing up for its public debut the following year, effecting a transfer from experimental to commercial operation. NBC continued to transmit from the Empire State Building, not only to the relatively few sets in homes but to TV receivers set up in public places; Germany and Russia were doing the same thing, also trying to catch up with the British. CBS opened the first of a number of TV studios in the building above Grand Central Station in New York City. One of this book’s authors remembers rehearsing and performing in those studios well into the 1950s, by then overcrowded and lacking the facilities necessary for efficient production. Key programming in 1938 included the first telecast of a Broadway play, Rachel Crothers’s Susan and God, and the first TV on-the-spot coverage of an unscheduled news event, when NBC’s mobile unit, doing a nearby story, picked up a fire that broke out on Ward’s Island. This latter happening had additional significance in that newspapers in various parts of the country carried the story with pictures they photographed right off the TV screen.

Fig 3.27 This statue honoring Philo T. Farnsworth in the nation’s capitol is inscribed “Father of Television.”

Photo by Lee Nadel.

1939

Television made its public debut in New York at the 1939 World’s Fair. On April 30, President Franklin D. Roosevelt officially opened the fair, with NBC televising the event to some 200 sets in about a 40-mile radius in the New York area and adjacent states. The timing, situation, and publicity marked this as the first public television broadcast, although, as we know, experimental stations had been offering programs to those who had receivers for a dozen years. The FCC had not yet decided on a lineage standard and would not officially authorize limited commercial television broadcasting until the following year. But RCA’s president, David Sarnoff, saw the World’s Fair as an excellent promotional opportunity for the RCA-backed lineage standard of 441 lines/30 pictures per second and for RCA-manufactured TV sets, which were demonstrated in a “Hall of Television” in the RCA Building at the World’s Fair.

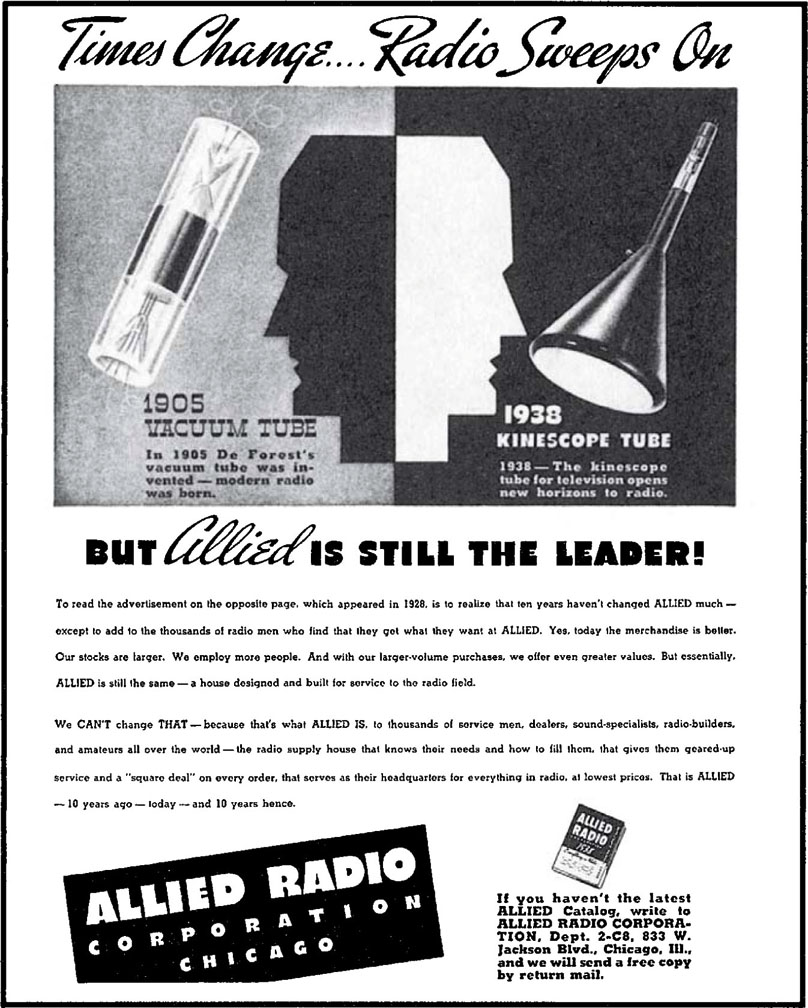

Fig 3.28 Time marches on as one new electronic medium exerts an impact on another in this 1938 magazine advertisement.

ERIK BARNOUW

BROADCAST HISTORIAN/WRITER

In 1939 Norman Corwin, a young CBS production man who had begun to impress management, was assigned to create, produce, and direct an Americana variety series to be titled Pursuit of Happiness, a CBS Sunday afternoon “public service” offering that was to include music, drama, comedy, and poetry. Corwin asked me to join him as writer-editor. I was to write the words for master-of-ceremonies Burgess Meredith, including his colloquies with guests. I was to have a budget for sketches by freelance writers. Since wars were in progress in various parts of the world, we decided on war and peace as a theme for one of the programs. For this I provided an opening from a Carl Sandburg poem, in which a little girl asks her father about war. He tells her that in wars, each side tries to kill as many of the other side as it can. The girl thinks about this a moment, then suggests:

GIRL: Sometime they’ll give a war and nobody will come.

I received word from the executive producer, Davidson Taylor, that my script was fine except for the opening, which would not do. I was asked to devise a new one. When I went to ask why, he pointed out that it was a time of wars, in which the United States might conceivably become involved. If so, it would not be good if CBS were accused of promoting draft resistance.

I was taken aback. I respected Taylor, who was knowledgeable in the arts and took his work seriously. Had I committed an error of judgment? When I told Corwin about the discussion, he was furious and went at once to vice president William B. Lewis, who had commissioned him to create the series. Word came to restore my opening. I felt gratified. The incident was characteristic of Corwin, who also took his job seriously.

The episode still resonates for me. I believe many network executives would have acted as Taylor did. The industry’s structure and tensions seem to condition people that way. They may be devoted to the Bill of Rights and cherish freedom of expression, but in troubled times they are ready, even eager, to walk in lockstep. They fall into line before a bugle has sounded. Yet in a democratic society, even after war has begun, is there really any reason why a person should not be permitted to suggest that—as any child can see—war is stupid, wreaking problems worse than it is supposed to solve?

Courtesy Erik Barnouw.

The broadcast industry supporters of the underdog got one of their few tastes of satisfaction in 1939. Vladimir Zworykin had developed the iconoscope and the kinescope, the tubes used in initial television transmission and reception, at RCA-NBC. Philo Farnsworth, who had developed a vital glass vacuum tube seal and the image dissector, had spurned an offer to work for RCA some years before and, during the ensuing years, had refused RCA’s money and pressure to buy his patents. Farnsworth and Zworykin had filed similar patent applications. In 1939, an agreement was struck between Farnsworth and RCA for cross-licensing. For the first time, RCA did not control the patents it needed and had to pay royalties to someone else for the rights.

One of this book’s authors remembers the landmark television broadcast at the World’s Fair. Like others seeing this phenomenon for the first time, he recalls the magic and excitement of standing in line and appearing in front of a camera while a friend stood at a monitor a short distance away and shouted and waved in wonder to confirm that one could actually be seen as a living, moving image at another site. Alternating places with his friend, he got in the long line again and again to assure himself that somehow the sending of one’s live image over the air wasn’t some trick and really could be believed. The other author of this book remembers visiting New York City as a small child and marveling at seeing himself on a TV screen in a department store.

NBC began regular programming at that time, adding to its World’s Fair coverage dramas, variety shows, sports, and special events. In May the first televised baseball game was presented. The New York Times, which in 1927 had reported the first test of television with the subheadline “Commercial Use in Doubt,” now reported that baseball could not be successfully shown on television, stating, “Baseball is a thrill to the eye that cannot be … flashed through space.”

Despite NBC’s efforts, people weren’t buying TV receivers in the way they had purchased radio sets almost two decades earlier. The cost of the RCA TV sets shown at the World’s Fair ranged from $200 to $600, which was, at a minimum, one to two months’ salary for a working person with a good job and as much as a year’s pay for those scraping by. The millions out of work couldn’t get money for food, much less for a luxury like television. But the potential was there, and by the end of the year eight manufacturers had produced some 5,000 TV sets.

Fig 3.30 Excerpts from a 1939 magazine advertisement promoting religious programming on radio.

Courtesy RCA.

Spurred by Edwin Armstrong, FM offered additional potential competition to AM, with 150 applications to the FCC for stations. Armstrong had demonstrated with his own FM station that his invention had several advantages over AM, including no static, comparable range with less power, and noninterference with other FM signals. The FCC barred educational stations from applying for AM frequencies, beginning the process that would result in almost all noncommercial or public radio stations licensed in the FM band. Today only some two dozen educational stations, most of them holdovers from the 1920s, are still broadcasting on AM.

The business of broadcasting found it necessary to both protect itself from a public that was beginning to be concerned with the impact of the media and to exert its own growing muscle for its own economic interests. The FCC issued a memo expressing concern with certain kinds of program practices, including lack of fairness in covering both sides of controversial issues, false or misleading advertising, frequent interruption of programs with commercials, excessive advertising, obscenity and profanity, racial and religious bigotry on the air, violence and torture on children’s programs, promotion of liquor, and too much recorded music. To prevent the enactment of federal regulations regarding such programming, the NAB issued a “Radio Code” that set new standards of practice regarding children’s programs; the number of commercial minutes allowed per hour in prime time; coverage of controversial issues principally in news and feature programs rather than in programs paid for by special interests (an action that, to some critics, meant keeping off the air any minority opinions); and fairness in news reporting. But compliance with the code was voluntary and had relatively little impact on actual broadcast practices. Radio stations, continuing their battle against paying music-use fees to ASCAP, decided to form their own music organization. Through the NAB, Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), was founded. Although BMI did acquire the rights to a fair amount of music, it was not able to replace ASCAP as the key provider, and the NAB-ASCAP contract negotiations continue today.

DAVID BORST

COFOUNDER, INTERCOLLEGIATE BROADCASTING SYSTEM (IBS)

The Intercollegiate Broadcasting System was founded in February 1940, when representatives from 13 colleges gathered at Brown University to plan the growth of campus-limited broadcasting at their schools. Ten of these colleges, Brown, Columbia, the University of Connecticut, Cornell, Holy Cross, Pembroke, Rhode Island State (now the University of Rhode Island), Saint Lawrence, Wesleyan, and Williams, are listed as charter members of IBS, although stations were in operation at only half of them. Dartmouth, Harvard, and the University of New Hampshire also sent representatives. To understand why this meeting was held, one must go back to the fall of 1936, when George Abraham and myself entered Brown. To enable his fellow students to hear his classical recordings and to permit two-way communication between rooms in his dormitory, George interconnected the output circuits of half a dozen radios in the building. The popularity of this novel scheme caught my attention, and I extended it to my dorm across the street, and even further. Before long a network of lines spread over the Brown campus, linking dozens of dormitory rooms.

Serious programming was inaugurated the following year over the “Brown Network,” and conversations were diverted to a second line paralleling the first. This second line was used to originate programs from points all over the campus, feeding into the main programming line at a central switching point. Approximately 100 radios were connected to receive the programs from the main program line. That’s how college radio was launched.

Reprinted with permission from The Journal of College Radio, a publication of the Intercollegiate Broadcasting System (IBS).

Fig 3.31 Excerpts from a 1939 magazine advertisement promoting religious programming on radio.

Courtesy RCA.

Fig 3.32 Brown Network board meeting (1940) in George Abraham’s dormitory room. George Abraham is in the center, and David Borst is on the far right.

Courtesy Dr. George Abraham.

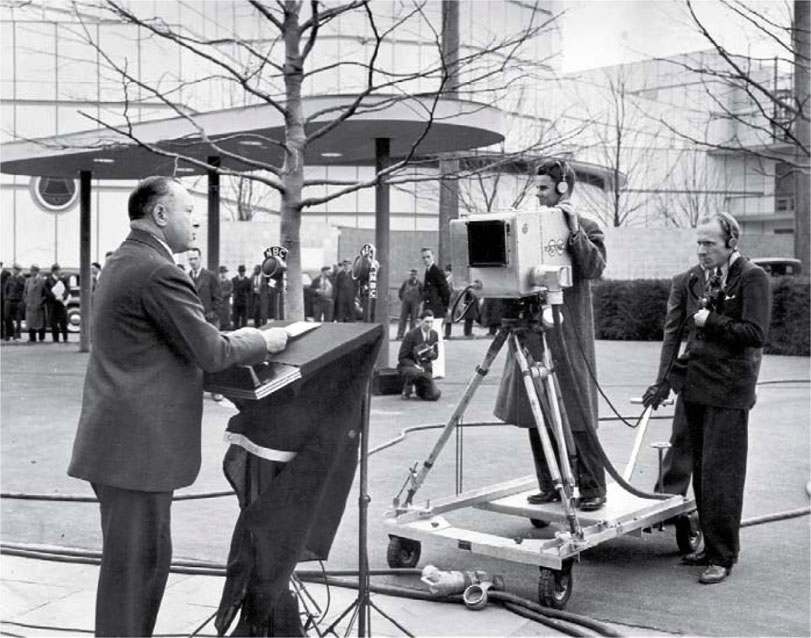

Fig 3.33 David Sarnoff debuts TV at the 1939 World’s Fair.

Courtesy David Sarnoff Library.