8. Testing Strategies

Professional developers test their code. But testing is not simply a matter of writing a few unit tests or a few acceptance tests. Writing these tests is a good thing, but it is far from sufficient. What every professional development team needs is a good testing strategy.

In 1989, I was working at Rational on the first release of Rose. Every month or so our QA manager would call a “Bug Hunt” day. Everyone on the team, from programmers to managers to secretaries to database administrators, would sit down with Rose and try to make it fail. Prizes were awarded for various types of bugs. The person who found a crashing bug could win a dinner for two. The person who found the most bugs might win a weekend in Monterrey.

QA Should Find Nothing

I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again. Despite the fact that your company may have a separate QA group to test the software, it should be the goal of the development group that QA find nothing wrong.

Of course, it’s not likely that this goal will be constantly achieved. After all, when you have a group of intelligent people bound and determined to find all the wrinkles and deficits in a product, they are likely going to find some. Still, every time QA finds something the development team should react in horror. They should ask themselves how it happened and take steps to prevent it in the future.

QA Is Part of the Team

The previous section might have made it seem that QA and Development are at odds with each other, that their relationship is adversarial. This is not the intent. Rather, QA and Development should be working together to ensure the quality of the system. The best role for the QA part of the team is to act as specifiers and characterizers.

QA as Specifiers

It should be QA’s role to work with business to create the automated acceptance tests that become the true specification and requirements document for the system. Iteration by iteration they gather the requirements from business and translate them into tests that describe to developers how the system should behave (See Chapter 7, “Acceptance Testing”). In general, the business writes the happy-path tests, while QA writes the corner, boundary, and unhappy-path tests.

QA as Characterizers

The other role for QA is to use the discipline of exploratory testing1 to characterize the true behavior of the running system and report that behavior back to development and business. In this role QA is not interpreting the requirements. Rather, they are identifying the actual behaviors of the system.

The Test Automation Pyramid

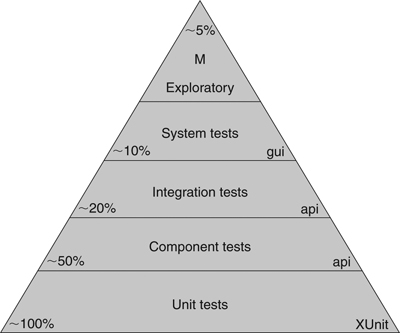

Professional developers employ the discipline of Test Driven Development to create unit tests. Professional development teams use acceptance tests to specify their system, and continuous integration (Chapter 7, page 110) to prevent regression. But these tests are only part of the story. As good as it is to have a suite of unit and acceptance tests, we also need higher-level tests to ensure that QA finds nothing. Figure 8-1 shows the Test Automation Pyramid,2 a graphical depiction of the kinds of tests that a professional development organization needs.

Figure 8-1. The test automation pyramid

Unit Tests

At the bottom of the pyramid are the unit tests. These tests are written by programmers, for programmers, in the programming language of the system. The intent of these tests is to specify the system at the lowest level. Developers write these tests before writing production code as a way to specify what they are about to write. They are executed as part of Continuous Integration to ensure that the intent of the programmers’ is upheld.

Unit tests provide as close to 100% coverage as is practical. Generally this number should be somewhere in the 90s. And it should be true coverage as opposed to false tests that execute code without asserting its behavior.

Component Tests

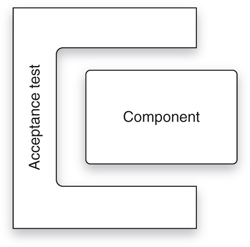

These are some of the acceptance tests mentioned in the previous chapter. Generally they are written against individual components of the system. The components of the system encapsulate the business rules, so the tests for those components are the acceptance tests for those business rules

As depicted in Figure 8-2 a component test wraps a component. It passes input data into the component and gathers output data from it. It tests that the output matches the input. Any other system components are decoupled from the test using appropriate mocking and test-doubling techniques.

Figure 8-2. Component acceptance test

Component tests are written by QA and Business with assistance from development. They are composed in a component-testing environment such as FITNESSE, JBehave, or Cucumber. (GUI components are tested with GUI testing environments such as Selenium or Watir.) The intent is that the business should be able to read and interpret these tests, if not author them.

Component tests cover roughly half the system. They are directed more towards happy-path situations and very obvious corner, boundary, and alternate-path cases. The vast majority of unhappy-path cases are covered by unit tests and are meaningless at the level of component tests.

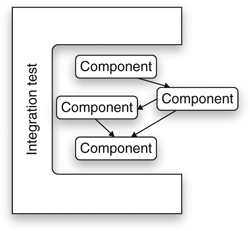

Integration Tests

These tests only have meaning for larger systems that have many components. As shown in Figure 8-3, these tests assemble groups of components and test how well they communicate with each other. The other components of the system are decoupled as usual with appropriate mocks and test-doubles.

Integration tests are choreography tests. They do not test business rules. Rather, they test how well the assembly of components dances together. They are plumbing tests that make sure that the components are properly connected and can clearly communicate with each other.

Integration tests are typically written by the system architects, or lead designers, of the system. The tests ensure that the architectural structure of the system is sound. It is at this level that we might see performance and throughput tests.

Integration tests are typically written in the same language and environment as component tests. They are typically not executed as part of the Continuous Integration suite, because they often have longer runtimes. Instead, these tests are run periodically (nightly, weekly, etc.) as deemed necessary by their authors.

System Tests

These are automated tests that execute against the entire integrated system. They are the ultimate integration tests. They do not test business rules directly. Rather, they test that the system has been wired together correctly and its parts interoperate according to plan. We would expect to see throughput and performance tests in this suite.

These tests are written by the system architects and technical leads. Typically they are written in the same language and environment as integration tests for the UI. They are executed relatively infrequently depending on their duration, but the more frequently the better.

System tests cover perhaps 10% of the system. This is because their intent is not to ensure correct system behavior, but correct system construction. The correct behavior of the underlying code and components have already been ascertained by the lower layers of the pyramid.

Manual Exploratory Tests

This is where humans put their hands on the keyboards and their eyes on the screens. These tests are not automated, nor are they scripted. The intent of these tests is to explore the system for unexpected behaviors while confirming expected behaviors. Toward that end we need human brains, with human creativity, working to investigate and explore the system. Creating a written test plan for this kind of testing defeats the purpose.

Some teams will have specialists do this work. Other teams will simply declare a day or two of “bug hunting” in which as many people as possible, including managers, secretaries, programmers, testers, and tech writers, “bang” on the system to see if they can make it break.

The goal is not coverage. We are not going to prove out every business rule and every execution pathway with these tests. Rather, the goal is to ensure that the system behaves well under human operation and to creatively find as many “peculiarities” as possible.

Conclusion

TDD is a powerful discipline, and Acceptance Tests are valuable ways to express and enforce requirements. But they are only part of a total testing strategy. To make good on the goal that “QA should find nothing,” development teams need to work hand in hand with QA to create a hierarchy of unit, component, integration, system, and exploratory tests. These tests should be run as frequently as possible to provide maximum feedback and to ensure that the system remains continuously clean.

Bibliography

[COHN09]: Mike Cohn, Succeeding with Agile, Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2009.