Organization of the Firm and Competition Law

We now move from common law into civil law. Firms generally take one of three forms: corporation, partnership, or sole proprietorship. There exists a variety of additional options, such as a syndicate, limited partnership, and other corporate structures. While the vast majority of enterprises operating in any country are organized as sole proprietorships, most individuals are employees of corporations and the majority of market transactions are conducted by corporations. In this chapter, we will examine firm organization, their economic reasons, and delve specifically into corporate law since this organizational form is the most important to the economy writ large.

Key Economic Concepts

antitrust arbitrage control General Theory of the Second Best |

monopoly grant natural monopoly ownership price discrimination |

Theory of the Firm Vickrey auction X-inefficiency |

Key Legal and Political Concepts

bankruptcy collateral damnum absque injuria ex ante ex post fiduciary duty |

indefinite lifespan indemnify limited liability per se rule public interest public–private partnership |

resale price maintenance rule of reason unlimited liability |

Benefits and Costs of Various Firm Organizations

Sole proprietorships are completely owned by only one individual. In some cases, married couples can jointly run the sole proprietorship under the theory of community property. Income is passed through to the owner’s income tax statement using Schedule C of the U.S. tax return. The sole proprietor runs the business and makes all decisions but is also solely responsible for company debts. Although this is theoretically unlimited liability, federal bankruptcy law does limit the total amount that can actually be collected. The paperwork associated with starting a business of this type is minimal. Debt financing is usually not an option beyond that available to an individual normally due to comingling of company and owner assets and liabilities. There is also no equity financing option. A major problem for the sole proprietor is raising funds.

Suppose an entrepreneur needs $1 million to start his or her firm but only a 40 percent chance of succeeding, a rate of success that is actually quite high relative to other firms. If the individual decides to borrow the money, they would face an exorbitant interest rate. If I can receive 2 percent on my money in a riskless endeavor by putting it into the bank, I would need to receive a 155 percent rate of interest just to break even on the deal based on expected returns. How did I arrive at this rate of interest if I am not a Mafioso? Simple: I need an expected return of 2 percent, which means I expect to receive back 102 percent of my investment in a year. However, 60 percent of the time, I lose everything. We calculate the return with x denoting what I need to receive in order to break even:

0.4(x) + 0.6(0) = 102

0.4x = 102

x = 102 / 0.4 = 255, which is the $100 in principal plus $155 in interest to be paid.

This high rate of interest is also why payday loans and other loans to poor credit risks command such high interest rates. If there is a high chance of default, the risk becomes unreasonably high to bear unless interest rates become usurious in nature. To allow individuals to borrow at reasonable rates, banks and other lending institutions insist upon personal loans and pledging of adequate collateral (oftentimes the personal residence of the entrepreneur) to secure the loan. There are other solutions that can be creatively derived but these would involve rather high transaction costs and might lead to endeavors of questionable legality (such as having a loan shark break one’s legs if one fails to pay the vigorish, otherwise known as the vig, the interest charged, oftentimes weekly, by the loan shark).

Is there another way to do this? Yes, we can form a partnership. Partnerships are a more complex form of organization and are a contractual form of organization whereby each partner assumes certain risks and receives certain rewards as specified in the contractual agreement that establishes the partnership. Every individual in the partnership has unlimited liability for the actions of the partnership unless they are protected under a limited partnership clause, which functions in a similar fashion to indemnification. An example of a type of arrangement that lacks such a limited partnership clause is found at Lloyd’s of London, which technically runs as a syndicate in that losses (and gains) are limited to the actual lines in which investors (known as names) assume risks. Thus if you invest in Lloyd’s of London’s ship insurance business, you are personally on the hook for all potential losses but only within that business line. If the earthquake insurance business is doing poorly, claims cannot be exacted against those in the ship insurance business. However, this also means that if the ship insurance business is doing poorly, revenues from a profitable line (for the sake of argument, personal injury insurance) cannot be used to pay for these losses. This compartmentalization limits the potential magnitude of losses but also reduces risk diversification, which is oftentimes the best means of reducing nonsystemic risk.

Issues with sole proprietorships are magnified under partnerships. If a sole proprietor dies, the proprietorship dies with them but a partnership is automatically dissolved every time a partner exits the business, including upon death. While this can be overcome with suitable contractual arrangements, transaction costs are very high. For example, a partnership can purchase life insurance on each partner’s life in order to maintain the capital necessary to continue but that means paying a premium each year that will likely increase dramatically as individuals age.

As a company grows in size, additional problems crop up. While the sole proprietorship can transfer ownership at will, the partnership must get the agreement of all partners. Furthermore, as you grow, you may find it beneficial to hire professional managers, but transferring control provides additional downsides due to unlimited liability: would you want to cede control of your company to professional managers who can harm your interests to such an extent that your own personal assets would be at stake? Yet failing to do so might limit growth opportunities since entrepreneurs rarely have the managerial skills necessary to conduct larger enterprises.

In order to limit such liability, sole proprietors might transfer risk through contracting by making the management company indemnify the sole proprietor against harm. Indemnification occurs when someone else takes on the responsibility for any loss caused by them. Indemnification can occur between any two parties. For example, authors indemnify publishers against charges of intellectual theft by representing the work produced is uniquely the author’s own work. However, indemnification only goes so far. If the individual is “judgment-proof” such as that occurs when there are few assets relative to the potential liability from which a plaintiff can recover, there will often be an attempt to go after the party with the larger amount of financial resources, a strategy known as a deep pocket search. Furthermore, why would a management company wish to engage in such indemnification unless they are compensated for that risk with a very lucrative management fee structure that brings us right back to the original lending problem that caused us to move on to the partnership form of organization in the first instance?

Alternatively, an owner could simply sell his or her interest to the workers themselves and create a worker cooperative. This allows the owner to cash out his or her interest and the workers would have the necessary incentives to carry on the enterprise in the owner’s absence. Or would they? While the sole proprietor has an interest in maximizing the value of the firm even as he or she plans to exit the business since the expected present value of the enterprise can be capitalized in its sale price, the worker has no such incentive once he or she leaves the firm. This is because a worker cooperative is a type of partnership in which the shares of the firm are nontradable and thus while they are entitled to a claim on current profits, either paid out as dividends or retained as earnings, it is unclear how to value potential future streams of income without a viable market mechanism to validate the overall value of the firm. This leads to a time horizon problem in which each worker views projects through a short-term lens that ends when he or she retires. Furthermore, it may lead to the company placing too much emphasis on worker retention since each worker realizes gains from both his or her employment contract as well as a residual claim on profits. As such, worker cooperatives can be less agile and adaptable to change than other enterprises. Even the claim that worker cooperatives will better take of workers is somewhat suspect. Unless all workers are equally exposed to workplace hazards, there is a public goods problem that is created with workers who are not as exposed to such risks being less likely to desire to reduce those risks than is optimal and those workers who are more exposed being more desirous to reduce those risks. While this can be overcome, as will be explored in the following chapter on environmental law, using negotiation strategies, such negotiations carry with them enormous transactions costs that may swamp any potential benefits from such mitigation.

The third method of organizing a firm is known as a corporation. While sole proprietors need no contractual form and partnerships have their origins in contract law, corporations originated as creations of the state. In exchange for a monopoly grant, they were required to carry out certain tasks in the “public interest” and really were “public–private partnerships” designed to raise large sums of private investment to carry out certain capital-intensive or risky activities the government supported. While certain mining corporations had already been in existence for hundreds of years, the modern corporation can be said to have originated with the Dutch East India Company in 1602. For the first time in history, the public trading of ownership interests (called stock) could occur in such a way that virtually anyone could participate. The Amsterdam Stock Exchange was created specifically to facilitate such trades.

That is not to say that stock did not trade among individuals before. Corporate stock had been issued for several hundred years, especially in the area of mining, which required vast sums of capital and high risk. There had also been “markets” of a sort such as the Leipzig trade fair where one could buy stocks in various German mining concerns as far back as the 14th century and the Venetians moneylenders used to carry around slates on which they quoted prices. There had even been a stock exchange in Antwerp where corporate bonds were traded. However, an exchange in which buyers and sellers could come together to trade common stock of a company and where arbitrage effectively conveyed information about a company’s perceived value and brought it in line with others in the market quickly and systematically—that was a new concept.

Joint-stock companies traded shares on an open exchange and had an indefinite lifespan (unlike partnerships or sole proprietorships), but did not enjoy limited liability. While limited liability was granted as a favor at times by the government, it was not until 1811 when New York enacted the first general limited liability law to help out its nascent manufacturing base that the modern corporation blossomed into its fullest form. The results were transformative. Market capitalization, which up until the mid-1800s was predominantly composed of bonds, shifted dramatically toward stocks by the latter half of the 19th century. Still, the potential for losing one’s investment never went away as countless investors have learned with every bear market.

Limited liability allowed investors to avoid active participation in decisions. Unlimited liability joint-stock companies also had separation of ownership from control, but they were playthings of the wealthy, not the masses, and the wealthy could significantly influence decisionmaking when they owned a significant portion of the stock. With the democratization of the stock market and widespread individual ownership of corporate stock, separation of ownership from control was no longer a matter of desire but rather one of necessity.

Unfortunately, separation of ownership from control creates a principal–agent problem. This can be addressed by requiring the officers of the corporation (the managers who are the agents in this example) to have a fiduciary duty to the owners of the company. This means that the owners (the stockholders) can sue the managers if they perform in any manner other than that which advances the stock owner’s best financial interests. Note that emphasis on financial interests, however. With a large disperse ownership, one could not maximize all potential interests. So the law has created a requirement to advance only the financial interests of the owners. Interestingly, this actually makes the corporation inefficient from the standpoint of economic theory since when you cannot maximize any one dimension, you shouldn’t maximize any of the other dimensions either but instead should seek a compromise if you want to continue to exhibit Pareto optimality. This result is an application of the economic theory known as the General Theory of the Second Best.1 An easy way of thinking of this is to suppose that you placed equal emphasis on profits and the environment. If it is impossible for me to maximize both, I should maximize neither in order to achieve an economically efficient outcome. This is because I want to ensure that each dollar that is spent gives me the most utility as opposed to the most money. It is a reason why we don’t work to exhaustion and why we don’t only consume one type of food. As there is diminishing marginal utility for any particular activity, the only way to maximize utility in the face of a constraint is to not maximize anything for which there is a tradeoff. Since there is a tradeoff between corporate profitability and environmental sustainability in the minds of at least some shareholders, one cannot guarantee that one will be economically efficient if one pursues only profits. Indeed, the fact that the agents (the managers of the corporation) are subsuming all goals but one (profits) when the owners themselves, if they were sole proprietors, would likely pursue other goals means that the principal–agent problem is not solved by appealing merely to their financial interests to the exclusion of all others.

Limited liability allows greater liquidity since approvals of stock transfer no longer required the assent of other owners. Before limited liability, the transfer of ownership to someone who was potentially judgment-proof due to low asset ownership created a negative externality for all other stockholders. They couldn’t allow dilution of liability to adversely affect their own interests. This creates a problem for bondholders: since owners no longer have unlimited personal liability, bondholders have an increased probability of default and a decreased potential amount of recovery in case of such default. This is yet another reason why the preferred form of raising capital has shifted to stock issuance from bonds.

Limited liability corporations still borrow considerable amounts of funds and bondholders still lend to corporations despite these risks. Why? The answer is that the market (as usual) has the answer: corporations pay higher borrowing costs due to limited liability than they would enjoy in the absence of limited liability. This is one reason why corporate bond debt (even at the AAA rating) costs more than similarly priced debt for the U.S. government, which only has an AA rating. After all, the U.S. government, by the very nature of its debt in that it only borrows in its sovereign currency, need never default. That does not mean that the U.S. government will never default, for it can do so and has done so in the past with the most recent default being in the Spring of 1979 when it failed to pay $120 million of bonds on time, an error that caused interest rates on government debt to spike about six-tenths of a percent for at least 6 months.2 Though the reason for failing to pay was described as “technical glitch” at the time, it nevertheless belies the notion that the U.S. government has always paid its bondholders in full and on time.

So what can a bondholder do to ensure that corporations pay them back? They can, of course, require the corporation to waive limited liability but they can already fully price the risk of default based on available information into the interest rate and so is unnecessary for publicly traded companies. However, there is still the risk that circumstances will change, not just that the corporation’s plans will cease to come to proper fruition but, more importantly, the corporation could seek to take on “excessive debt” that dilutes the likelihood of being fully paid back. Furthermore, the corporation might take funds from one project and apply them to another. To guard against these potentialities, bondholders (and banks that directly lend to corporations) may require securitization of debt or enforcement of covenants that preclude the corporation from engaging in activities that would materially affect its ability to fully realize its bond obligations.

For the corporation with liabilities that exceeds its assets, the law provides, similarly to that of an individual, the possibility of bankruptcy. Of course, personal bankruptcy provides a true upper limit to even the unlimited liability required of the sole proprietor or the investor in a partnership. It might, therefore, seem unnecessary for corporations to also have a bankruptcy option. After all, a corporation that has liabilities in excess of its assets is only required to hand over the assets to the creditors, while the shareholders can walk away with no further liability than the loss of their investment. However, the right of bankruptcy exists for both debtors and creditors. While the debtor can discharge debts in a voluntary bankruptcy and thus limit overall payments to creditors, the creditor can force a debtor into bankruptcy through an involuntary process as well.

This serves to protect the creditor from having other creditors because the more creditors that a firm has, the more likely one creditor will take an action that harms another creditor. An example of this is that which happened to Simulations Publications Inc. when it failed in 1982. SPI was, at the time, the largest producer of war-games in the world but it still did not use this position to secure any type of market power and it was still a tiny company with only a few million dollars a year in sales. Its most important asset was the magazine Strategy and Tactics, which had 30,000 subscribers.3 However, close to 1,000 of these were lifetime subscribers who had paid a $300 one-time subscription fee in exchange for a perpetual subscription.4 A subscriber pays money up front with the promise of receiving issues in the future and that makes them creditors of the company at least until the end of their existing subscriptions but these subscribers were due a perpetuity ad infinitum. Given the high interest rates that occurred at the time, these perpetuities were actually not worth very much. In 1982, the annual subscription price was $20 and the prime lending rate was at 17%. A perpetuity’s value is the annual rate divided by the interest rate. This leads to a nominal value of about $120. That wouldn’t have worked given the contractual terms of the lifetime subscription stated subscribers could cancel their subscriptions and receive their $300 back less a $2 per issue cost for each issue that they had previously received. With that in mind and based on when lifetime subscriptions were offered, the owed amount to these 1,000 lifetime subscribers would have been about $250 each or $250,000. In addition, there were about 30,000 other subscribers. Assuming that each subscriber still had half their subscription remaining, the total amount owed to subscribers alone was in excess of $500,000.

That was the least of SPI’s worries. It had tapped out all its borrowing options and had even taken $300,000 from venture capitalist firm, Alan Patricof Associates, which was upset at the burn rate that SPI was running through the money. It was at this point that SPI turned to the publisher of Dungeons & Dragons, TSR, a company that was about 10 times larger, for a nearly half million dollar loan and used much of the proceeds to pay off the venture capitalists in full. SPI secured the loan by pledging all of its intellectual assets. In so doing, TSR became a secured creditor and moved to the top of the list. When TSR called the loan a few weeks later, SPI could not pay and TSR took the collateral, which essentially made SPI worthless as an entity. Upon looking over the books, TSR was shocked to see the extent of its potential liabilities and refused to honor the existing subscriptions. Claiming that it took possession of assets but not liabilities, TSR ended up paying off a few of the corporate creditors but did not honor the subscriptions or the preorders.5

This example illustrates what can happen when a side deal to allow for the clean exit of an investor occurs before a company can be placed into involuntary bankruptcy. If SPI had been moved into bankruptcy, subscribers and individuals who had preordered product might have had an opportunity to recover at least some of the cash that they had expended. This problem would occur as well if the company simply paid off some creditors in advance of others. Those creditors who were paid off in full end up diluting the remaining assets that could have served the other creditors. Therefore, bankruptcy protects the positions of creditors who might not have as detailed knowledge as others of the financial precarity of the firm in question. Of course, the problem could also have been solved by ex ante contracts between creditors and the SPI as well as between subscribers and SPI but such contracts would have necessitated greater disclosure of the financial problems of SPI to their subscribers, which might have dimmed the desire of individuals to subscribe in the first instance, thus speeding up the failure of the company. Given the small value each subscriber had in the overall company, it would have been too expensive for any to place SPI into involuntary bankruptcy. Only one of the larger creditors could have done so and TSR effectively shut them up by paying them off. The irony was SPI’s underlying value lay in its customer base, which TSR destroyed by refusing to honor the subscriptions or preorders.

Rather than force a company into involuntary bankruptcy, a company can voluntarily place itself into bankruptcy and undergo corporate reorganization. In such a plan, corporate debt is converted into stock and existing stockholder shares are diluted as a result. Existing shareholders almost always prefer this option since it typically preserves at least some capital for them. Management always prefers this option since it allows them to remain in place as debtors in possession through the reorganization planning process, which can last up to 6 months. Creditors can object to this transference but if the firm has more value as a collective entity with existing management in place, it can end up not only preserving value for the creditors but actually help them receive more money than they initially would have been entitled to under the original repayment plan. Furthermore, at times, insolvent firms may still be valid going concerns if only they can solve short-term liquidity problems brought about by a need to pay off current liabilities. When credit markets seize up, such as that which happened in the 2007–2009 recession, even wellmanaged firms can find themselves facing liquidity constraints and debt repayment requirements that could make them temporarily insolvent. However, if they can find a way to outlast this period, they could end up returning more than their obligations to everyone concerned.

Alternatively, the firm cannot cover its total costs but still can cover variable costs once debt payments are alleviated. In such cases, liquidation reduces overall payments to the creditor. Consider a firm that owes $100 million at 10 percent interest and it is supposed to pay $10 million each year in principal payments until the debt is satisfied. Suppose further, the firm has $5 million in equity and makes an operating profit before considering the loan of $15 million a year. This year, the firm must make a $20 million payment on its debt but the $20 million payment necessitates the complete wipeout of all equity. The firm is technically bankrupt and the following year, the firm will be unable to make its required payment of $19 million ($9 million in interest and $10 million principal payment) since it would then have a loss of $4 million with no equity from which to draw. The problem for the creditors is forcing the firm into bankruptcy will mean they will be paid just $20 million total (this 1 year’s payment). However, if they suspend payment of interest, the firm can continue to pay them $10 million every year indefinitely. Alternatively, they can demand a principal payment of only $5 million this next year. Although the firm now takes 20 years to pay off the loan, the creditors can recoup their entire investment.

A pesticide plant has a gas leak that exposes half a million people to toxic gases. A tobacco company sells a product it knows to be highly addictive and carcinogenic. An automobile manufacturer sells a car that it knows is defective and decides against recalling it, reasoning that the payment of a few dozen accidental death claims will be less than the cost of replacing defective parts. All of these actions constitute torts that give rise to potential involuntary debts on the part of the corporation. Provided these actions can be considered accidental, they can be covered by insurance but deliberate malfeasance is not covered and the corporate veil can be pierced, allowing potential exposure to unlimited liability for the shareholders in such circumstances.

This is not ordinarily the solution proffered since shareholders are not usually responsible for these actions. In circumstances where the shareholder himself or herself is the source of the tortuous behavior (such as when a subsidiary corporation of a parent corporation is borrowing and the assets of the subsidiary corporation are misrepresented by the parent corporation or in the case of a closely held corporation where the owner and manager are one and the same person), piercing of the corporate veil may be appropriate. Similarly, a closely held corporation formed for the sole purpose of reducing exposure may find itself having this plan backfire if it is determined that its principals deliberately engaged in risky behavior to the point of negligence because they were counting on the limited liability afforded to them as being a corporate entity.

Companies engaged in risky activities might choose to be undercapitalized relative to potential liability. Instead they distribute profits through enhanced dividends, basically playing a game of Russian Roulette until a tort manifests itself. Since tort victims have the same standing as other unsecured creditors, such firms not only find themselves with limited share capital but also high secured debt. Larger companies protect themselves from large-scale liability by creating wholly owned subsidiaries to engage in these activities. Because subsidiaries are not being created for purposes of misrepresentation but rather serve a valid corporate use (since in their absence, the firms will be merely spun off and end up severely undercapitalized anyway), it is unlikely a court will allow the exposure of the parent corporation’s assets to pay a tort judgment of its subsidiary.

Another way to solve this from the corporate standpoint is to securitize your accounts receivables or sell them outright. When I ran a small gaming company, we used to find ourselves running low on cash since accounts receivables were due in 90 days while accounts payables were due in 30 days. We would sell our invoices at a discount to collect cash up front, a process known as factoring. At that point, our assets were transformed from accounts receivables to cash, which is obviously much more liquid. If the firm then turns around and distributes this cash to its investors or if it pledges its invoices to a secured creditor, this money is off-limits to tort victims.

Transaction Cost Theory of the Firm

Businesses necessitate enclosing certain types of transactions within a legal structure and prohibiting them from occurring outside of that structure, thus effectively prohibiting free trade that would make both parties better off. So why creates businesses? The answer is, once again, transaction costs. Each time we buy, we conduct a deliberative search and acquisition process that can be quite costly, especially for small items. These costs, associated with each transaction, are called transaction costs and can become quite a significant proportion of the overall bill.

Suppose the night before Valentine’s Day, I wish to purchase a gallon of milk, three pounds of apples, two pounds of hamburger, a box of oatmeal, one dozen roses for my wife, a set of batteries, a light bulb, a video game for my youngest daughter, a book for my oldest daughter, and a pair of pants for myself because I have been losing so much weight. I could get some of these items at the grocery store, but not all of them, and the grocery store is much closer than is Wal-Mart. In addition, the grocery store is currently having a special deal on flowers. Wal-Mart has all of these items but it also has a long check-out line. The prices are better on the video game at GameStop, where I can buy the game used (my daughter does not really care if the game is used or new), and I can get a better deal on the pants if I go to the Men’s Wearhouse.

If I want to minimize overall costs, I need to consider factors other than price. There are direct costs, such as gasoline and increased maintenance costs of longer drives. More importantly, are indirect, or opportunity costs, including the time it takes to drive to each location and the time spent in each store. I could decide to spend less time driving and order some items from Amazon but everyone wants everything right now, so that isn’t much of an option and it represents yet another cost: the cost of waiting. There is also the aggravation associated with it all. I could try to ask my wife to do these things but since it is almost Valentine’s Day, it will probably end up costing me significantly more than flowers to make it up to her—the last time I didn’t buy her flowers, I ended up having to buy her a diamond necklace at Macy’s. Ouch!

So what do I do? I wait until everyone is asleep, jump in the car, and go to Wal-Mart and buy everything except for the flowers since they are sold out. Luckily, on my way home from the store, now certain that I will have to pay for a necklace once again this year, I spy a still-open florist shop that is selling a dozen roses for $80, about twice what it would have cost if I had thought about ordering them in advance, but that still beats the price of the diamond necklace, so I buy it.

So, why did I go to Wal-Mart instead of driving all over town? Wal-Mart effectively minimized my overall costs (including transaction costs). Business organization is similar in nature. Think about the costs associated with a hamburger restaurant. There are acquisition costs associated with acquiring a new customer. There are costs of the food that is used in meal preparation. While it may be possible for a restaurant to acquire its meat and bread cheaper if it shops around, the consistency of the product may not be as high as if the restaurant purchases goods from one supplier. Similarly, if the restaurant decides to become a franchisee instead of going it alone, it is possible that customer acquisition costs can be lowered significantly. While this is going to cost the restaurateur in terms of a high franchise fee to go with one of the national chains and it will mean an inability to differentiate the product from those of the other franchisees, buying into a national restaurant chain will typically entail a location monopoly for the restaurant over a few square miles when it comes to that particular chain’s locations. This opportunity cost is capitalized in terms of the franchise fee that the restaurateur pays to the national chain.

Businesses internalize production when transaction costs associated with markets are so great that it would overwhelm cost savings associated with competition. On the other hand, if cost savings from competition outweigh transaction costs, businesses will contract with others to provide those services. As companies grow, they end up finding that it makes more sense to internalize operations since transaction costs associated with going to the market tend to dominate (or they sign an exclusive contract that is an intermediary position from conducting continual market transactions and internalizing the activity). That is because every time a business engages in a market transaction, it pays a transaction cost and, when businesses grow, they tend to become more efficient in their operations, thus reducing benefits from the marketplace. As when I go to Wal-Mart for everything, businesses find that internalizing operations reduces transaction costs to such an extent that it compensates them for extra costs associated with not entering into the competitive marketplace for commonly purchased items.

In writing this book, I placed myself into competition with similar books in the field of law and economics. Thus, sales of my book may reduce sales to other authors. In fact, I might cause them grave harm. But do any of them have a legal action against me?

While certainly my actions result in an externality for them, this is what is referred to as a pecuniary externality, one that manifests itself in changes in pricing rather than directly affecting the production or consumption of another. In order for them to have just action against me, I would have to behave in an anticompetitive manner, rather than a competitive one.

The earliest case law is found in Hamlyn v. More, Y.B. 11 Hen. 4, fol. 47, Hil., pl. 21 (1410) (Eng.) in which two schoolmasters tried to enjoin a third from providing schooling in the town of Gloucester, arguing that the action of entering into competition caused a decline in their livelihoods, reducing the customary fees from 40 pence to a mere 12 pence per term. Justice Hankford noted that although there were damages, it is possible that there was no injury (damnum absque injuria), just as the case when a mill opens near another mill, thus causing a loss of business. However, if the other mill dammed up the stream so that water no longer flowed to the second mill, the second mill owner would have cause for damages under the law of nuisance. This is the first time that the distinction between pecuniary externalities (in the first instance) and real externalities is manifested in legal doctrine and the court decided in favor of the defendant.

Virtually all things cause pecuniary externalities. My decision not to purchase a computer causes a loss of business from the seller of that computer but this is not a tort either. The key determination in deciding whether something is tortuous is whether there is an interference with an inherent right. In an earlier case from more than a hundred years before, Prior of Coventry v. Grauntpie, De Banco Roll, Hil. 2 Edw. 2 (No. 174), r. 151 (1309), the court found that the granting of a monopoly by the government could forestall competition since allowing others to compete would interfere with a right that was explicitly granted by force of law.

Antimonopoly Law

On the other hand, when rights are not granted by force of law, a cause of action can be made against the monopolist provided the monopolist acquires or attempts to maintain the monopoly through anticompetitive means. Contrary to what many believe, having a monopoly is not illegal. Indeed, if one were to take it to the extreme, all property rights convey some type of monopoly power to their rights-holder. I have a monopoly over the use of my intellectual property as well as my physical property in that no one can utilize these without my consent. However, this isn’t typically what an economist means by a monopoly. By a monopoly, an economist means that the company is the sole provider of the good or service and that there are no close substitutes. Thus, although Burger King has a monopoly over the Whopper sandwich, it is not a monopoly because the Big Mac from MacDonald’s is a close substitute.

Monopolies arise in two basic ways. First, is a pure monopoly, which arises either because of sole control over a basic resource (such as might occur if a company owned all of the diamond mines around the world) or by grant of force of law. Examples of these are patents that grant a monopoly over the implementation of an idea for a limited duration of time, and government franchises such as the monopoly that your electric company likely has in your city or town.

Second, a monopoly could naturally arise as it is economically efficient for there to be only one provider of a good or service. This occurs when there are very high fixed costs, resulting in a situation in which the lowest long-run average cost will not be achieved unless there is only one firm in the market. Economists call this type of monopoly a natural monopoly. Such monopolies (and monopolies in general) produce at an inefficient pricing point unless they are regulated since the profitmaximizing Price does not equal Marginal Cost (P ≠ MC). As the firm lowers price, it must bestow the same reduction on all market participants, so Price exceeds Marginal Revenue (P > MR). As firms produce where Marginal Revenue = Marginal Cost (MR = MC), this implies P > MC. Furthermore, since firms must at least make their average costs in order to stay in business, allocative efficiency cannot be achieved unless the monopoly is subsidized. Because this is usually politically unpopular, monopolies are usually regulated and allowed to produce where their average costs are covered, as illustrated in Figure 5.1. If at least their average costs are not covered, the firm would have to be subsidized.

Economists have identified three major complaints about monopoly: (1) deadweight losses, (2) rent-seeking behavior, and (3) X-inefficiency. Deadweight losses occur when firms are not allocatively efficient and thus P > MC. Rent-seeking behavior occurs when individuals either within a firm or within a regularity or legislative body raise the regulated price to enrich themselves. X-inefficiency is an increase in the marginal cost of doing business that occurs when firms are not subject to competition and thus do not achieve cost minimization.

Anticompetitive Measures

Anticompetitive measures are illegal activities that reduce competition. They may be practiced by monopolists or by firms that are in imperfectly competitive markets and that have the power to set price as opposed to being price takers. While state laws regulate intrastate commerce, the Federal Government’s jurisdiction only applies to interstate commerce. The definition of interstate commerce is both broader and narrower than what many believe. In Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, et al. 259 U.S. 200 (1922), the Supreme Court ruled that Major League Baseball was not engaged in interstate commerce despite teams crossing state lines, noting “a firm of lawyers sending out a member to argue a case, or the Chautauqua lecture bureau sending out lecturers, does not engage in such commerce because the lawyer or lecturer goes to another state.” Yet, in Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964), it ruled that racial discrimination in restaurants was unconstitutional because it harmed interstate commerce, even if the restaurant did not significantly engage in such commerce.

The Sherman Act of 1890 makes conspiracy to restrain trade or use anticompetitive means to monopolize a market illegal. Actions may be brought by the government or any party injured due to anticompetitive actions. The Supreme Court said the “purpose . . . is not to protect businesses from the working of the market; it is to protect the public from the failure of the market. The law directs itself not against conduct which is competitive, even severely so, but against conduct which unfairly tends to destroy competition itself.”6 Many early cases were not directed against corporations but were against labor unions to force them to return to work. When workers ignored court injunctions against striking, they were found in contempt of court and sentenced to prison. Eugene V. Debs, the famed labor organizer, was convicted of contempt of court for refusing to disband a strike. His conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court, which laid the groundwork for antagonism between labor unions and the court system for two generations.7

Whether anyone is actually harmed in the process is immaterial so long as it is “by and of itself” illegal under the per se rule. In United States v. Addyston Pipe and Steel Co. 85 Fed. 271 6th Cir. (1898), the court determined that an agreement is per se illegal if its purpose is to restrain trade. This is different from the “rule of reason” in which an agreement that serves another legitimate purpose is only illegal when the restraint on trade that results from that agreement is either unnecessary or broader than necessary to serve that legitimate purpose. In other words, a violation of the rule of reason occurs when the restraint on trade is unreasonable.

The Clayton Act of 1914 specifically exempted unions from its effects and prohibited mergers and acquisitions, tying or exclusive dealings, or price discrimination where these significantly reduced competition. It also prohibited the creation of interlocking directorates wherein one or more individuals appear on the board of directors of competing companies.

When government mandates price fixing, like minimum wages, its actions cannot be construed as anticompetitive, but the Supreme Court has been equivocal regarding private price fixing. It ruled resale price maintenance that prohibited retailers from selling below a price specified by a manufacturer was per se illegal in Dr. Mills Medical Co. v. John D. Park and Sons Co., 220 U.S. 373 (1911) but ruled in Schwegmann Bros. v. Calvert Distillers Corporation, 340 U.S. 928 (1951) that it was legal, provided state law allowed it. It found prohibiting retailers from charging more than a specified price was a per se violation in Albrecht v. Herald Co., 390 U.S. 145 (1968), leading many firms to add the proviso “Available at participating retailers only” when sales were advertised, but it overturned that ruling nearly 30 years later in State Oil Company v. Barkat U. Khan and Khan & Associates, Inc, 522 U.S. 3 (1997).

From an economics perspective, these latter decisions make for better public policy since price ceilings can reduce customer uncertainty over retail pricing, while retail price maintenance polices allow retailers to engage in nonprice competition and offer superior service and salespeople who are knowledgeable about the products sold to consumers.

Mergers

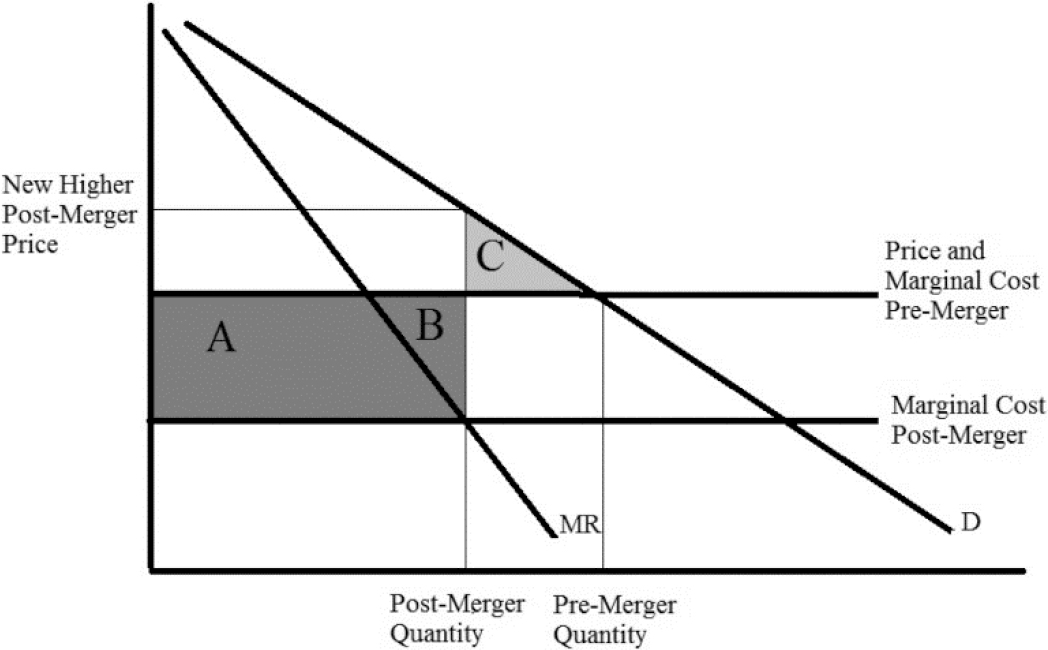

Market tradeoffs exist when firms engage in technologically beneficial mergers. If the government uses a total welfare test to approve mergers, some mergers should be approved even though they tend to create market power. If there are synergies to be found that reduce costs, society benefits in allowing these to occur whenever cost savings from the merger exceed deadweight losses from greater monopolization.8 Figure 5.2 illustrates this. Before the merger, the two firms engage in competition but after the merger, they become a monopoly, raising the price of their product. Cost savings are demonstrated by A and B (since the combined firm realizes increased efficiencies of scale) and the deadweight loss associated with monopolization is shown by C. In terms of efficiency, if Area C > (Area A + Area B), the merger should be rejected but if Area C < (Area A + Area B), the merger should be approved.

Figure 5.2 Economics as an antitrust defense

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is the practice of charging different prices to different customers. When firms have monopoly power, price discrimination serves to reduce the associated deadweight loss but it also tends to reduce consumer surplus. There are three forms of price discrimination.

In first-degree (or perfect) price discrimination, every customer pays the highest price that he or she would be willing to pay to receive the product. This eliminates all consumer surplus but allows the producer to sell along the full range of the demand curve so there is no deadweight loss either. While this is never possible in practice, in the case of unique items that which comes close to this is what is referred to as a Vickrey Auction. In a Vickrey Auction (similar to what occurs on eBay), the winner of the auction receives the item at the price of the second-highest bid plus a small charge to ensure that theirs is the highest bid, but since this total is no higher than the actual bid of the winner, there is an incentive to provide one’s true reservation price (in the case where two bids are the same, the earlier bid takes precedence and no additional charge is required).9

In second-degree price discrimination, buyers receive quantity discounts, paying a lower price for buying in bulk, while in third-degree price discrimination, buyers pay a different price depending on their membership in a particular group. For example, children pay less for entrance to a movie theater than do adults and students pay less for software than other customers.

Unless the third-degree price discrimination requires the consumer to overcome a hurdle (such as clipping coupons), arbitrage needs to be eliminated for it to make business sense. Individuals receiving the discounts cannot simply turn around and hand reduced-price items to a third party who does not qualify for the discount. That is why children do not receive discounts on popcorn at the movie theater. The cinema can bar entry by an adult on a child’s ticket but can’t stop the adult from eating the child’s popcorn (though the crying child might preclude that activity!).

In many states, differential pricing based on gender is illegal unless it is based on actual cost differences. Life insurance companies can charge men higher rates since they are statistically likely to die earlier and barbers can charge less for haircuts typically sought by men than those given to women given the time required to cut hair may differ by gender, although pricing in such cases may be challenged when the actual cut sought is identical. However, charging men and women different prices solely based on gender where there is no cost differential is a little more questionable. In California, under the Gender Tax Repeal Act of 1995 and the Unruh Civil Rights Act of 1959, an event such as a “Ladies Night” is illegal since the effect is to charge male patrons more than female patrons even though both are receiving identical services.10 However, under Hollander v. Copacabana Nightclub, 624 F. 3d 30 (2d Cir. 2010), such actions are not a violation of either federal or New York state law.

When discrimination concerns a retail establishment, price discrimination is illegal under the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936 unless it can be justified by either cost considerations or to meet a competitor’s price. The cost consideration argument, however, needs to be qualified since the quantity discount needs to be actually and reasonably available to all, not merely available to all in name only. In Federal Trade Commission v. Morton Salt, 334 U.S. 37 (1948), the Supreme Court ruled that when a quantity discount was available to only a limited number of large buyers, it was illegal: “The legislative history of the Robinson-Patman Act makes it abundantly clear that Congress considered it to be an evil that a large buyer could secure a competitive advantage over a small buyer solely because of the large buyer’s quantity purchasing ability.”

Interestingly, the Act allows affected companies to sue not just the company offering the discount but also those receiving the discount. In addition, trying to protect wholesaler margins by offering different prices to wholesalers and retailers can also be illegal when wholesalers enter the retail business in an effort to utilize these discounts to undercut the competition under the Supreme Court decision in Texaco, Inc. v. Hasbrouck, 496 U.S. 543 (1990).

Remedies

When a violation occurs, remedies usually take the form of injunctions against the specified activity. However, these injunctions may be difficult to enforce without additional measures. As such, consent decrees usually are offered wherein a series of steps are listed that the company must engage in or a penalty will be enacted up to or including divestiture to reduce monopoly power. Alternatively, damages can be awarded that serve to disgorge the profits that were realized from the monopoly action either in the form of rebates to consumers or by paying the penalty directly to the federal coffers.

1. Why might an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) run by a trustee have a better incentive structure than a worker cooperative, in which the company is run directly by the workers?

Employees may prefer to maintain their jobs than improve profitability. In addition, workers nearing retirement would have shorter time horizons and thus make decisions that were not always in the long-term best interests of everyone in the firm.

2. Predatory price discrimination, the selling of a good or service below average variable cost or marginal cost, has often been a complaint directed at large successful companies. Why does this argument make no economic sense?

Any firm that actively charged below its costs would soon find that it could not compete. Either the company must be charging less with the hope that it can sufficiently increase production so as to see a sufficient reduction in its marginal costs due to greater economies of scale to justify the price reduction (and therefore it no longer would be charging below cost) or it must be doing so as a threat and plans to raise prices as soon as competition evaporates. The problem with this strategy is that the threat of competition never goes away unless it is completely eliminated and, even then, it cannot be assured of being eliminated unless the price set by the monopolist is sufficiently low so as to preclude new entrants. The only way around this is by executing a credible threat to forestall future competition, but this entails building excess capacity, which itself is costly, but which serves to reduce marginal costs (while simultaneously increasing fixed costs) and thus lowers the threshold amount wherein a price can be declared predatory. However, once that capacity is built, economies of scale kick in, which means that a law against predatory pricing tends to establish natural monopolies!

3. Harris Teeter, a supermarket in North Carolina, offers a 5 percent discount on Thursdays to people above the age of 60 years. There is nothing that prevents someone from bringing his or her parents to shop with them for groceries that the younger shopper will actually be using. Does this violate the argument that third-degree price discrimination requires arbitrage be eliminated for the policy to make business sense?

No, Harris Teeter’s policy is really more of a gimmick than an attempt to practice third-degree price discrimination. Like Ross, a national discount clothing store that offers seniors a 5 percent discount on Tuesdays, its policy is more akin to advertising, serving to generate repeat business from a particular clientele. While either could just as easily lower prices for everyone on those days, these well-known policies serve to reinforce the brand among a group that tends to be more brand loyal than younger consumers.

1. While prices are higher under monopolies, costs can be higher as well since a lack of competition means that there is little incentive to control costs. What does this mean in the long-run for potential maintenance of monopolies?

2. How does limited liability distort incentives for corporations?