Why do interviews go wrong?

THIS CHAPTER LOOKS AT:

- What typically goes wrong, and why

- The misguided assumptions we make about interview results

- Seeing the difference between long shots and near-misses

- The 10 per cent rule

- What decision makers say about the process

NOT QUITE THE RESULT I WAS LOOKING FOR ...

Having looked at what a great performance looks like, time for some diagnostics about what can go wrong. Interviews do sometimes get you unpredictable results. If you knew exactly why, you’d adjust your performance unassisted and you wouldn’t need this book.

Some activities in life are fairly predictable, but job interviews present several multiple, mysterious realities:

- Questions came up that you didn’t expect.

- You found it difficult to think up good examples under pressure.

- The interviewer did all the talking.

- You didn’t get a chance to talk about the things you had in mind.

- The interviewer seemed to be talking about a different job to the one you applied for.

- You never really warmed up.

- It seemed to go brilliantly but you never heard anything again.

- It went OK, but you aren’t sure that the interviewer will remember you.

Even experienced workers or people who have been on the job market for a long time are not terribly good at interpreting what happened in an interview. Candidates often say ‘it was a terrible interview’ and get invited back, while others say ‘it went like a dream’ and get an impersonal rejection letter.

JOINING THE DOTS

Just as frustrated authors collect rejection slips from publishers, some candidates proudly count ‘no’ letters. When an employer is sifting paper applications, the chances of getting short listed are always pretty small if the field of applicants is large. If there are 500-plus people chasing a job the odds are against getting an interview, no matter how brilliant your application is. That’s an important reality check that cuts through the randomness of the job market (but see Chapter 19 for more on your job search ‘statistics’).

‘There are two types of interview’, explains career consultant Robin Rose. ‘The first is a structured interview, probably by a HR professional, which looks in detail at skills required for the job. This is essentially for ruling people out. If you can match the basic requirements of the job you can probably get through this without difficulty; the second is a selection interview where the criteria are not about skills and experience but about why you should be offered the job. In the second type, a positive attitude really matters.’

Second-guessing a recruitment decision is a slippery game. With a lack of real evidence, you may draw your own, wrong, conclusions. If you get a ‘no’ letter it’s very tempting to believe you can join the dots and decide how and why you didn’t get an offer. You might blame the lack of professionalism of the interviewer. Even more likely, you will blame yourself: ‘I don’t interview well’ is a far more common statement than you might think.

SEEING THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ‘NO’ AND ‘NEARLY YES’

There is a big difference between an interview that rules you out, and one that very nearly rules you in. Don’t read more into the interview result than you actually see. You may have put in a convincing performance but just lacked a little bit of sector knowledge. You may have been up against an internal candidate who was informally promised the job 18 months ago. Let’s be clear: most times the real reasons for hiring decisions will always be completely hidden from you.

The offer of an interview probably means that you have the skills and knowledge to do the job, but sometimes with more junior jobs these things are not tested until you are in the room. So if your interview feedback is ‘post holders need the European Computer Driving Licence’, it’s a good reminder to:

- double check employer requirements in advance;

- either get the minimum qualifications you need or learn to talk about appropriate, equivalent experience.

THE 10 PER CENT RULE

New businesses are often founded on an interesting principle. You don’t have to invent a completely new service or product, and you can even set up in direct competition with other businesses, as long as you offer something that is different by 10 per cent – you might be 10 per cent faster, cheaper, better quality. That 10 per cent is enough edge.

The same rule applies to improved job interview performance. Think of a recent interview experience. If you were able to answer all questions positively and clearly with good evidence, then the job probably fits the ‘nearly yes’ category. Well done. That means you are getting results. You probably don’t need to reshape what you do, but next time you need to do something 10 per cent better – better answers, better voice, better body language, better evidence. Small changes have huge leverage.

WHY DO PEOPLE (STILL) GET INTERVIEWS WRONG?

The nation’s favourite interview strategy is still ‘I’ll wing it’. This often means ‘I don’t know what they will ask me but I will just be myself’.

Imagine your boss invites you to a meeting next month about your long-term prospects. This meeting will have a big impact on the next stage of your career. No sensible person would go into that meeting without being prepared to talk about achievements, special skills and knowledge, preferred working conditions, and the future. Job interviews often have the same life impact, yet we approach them planning to improvise.

WHAT GOES WRONG?

Candidates are notoriously poor at judging their own performance in all kinds of assessments, including interviews. So, whether you thought it was a good or bad interview may not be relevant. You have no idea who you are up against, and probably only half an idea of what the interviewer is looking for. Don’t get stuck in ‘if only’ mode: ‘If only I had more experience, better qualifications, more confidence ...’ Behind this wish to reinvent yourself is a huge misunderstanding – that an employer is looking for, and will find, the perfect candidate. All recruitment is a compromise – employers rarely get exactly what they are looking for. Recruiters will tell you that the person who gets hired is the one who matches most areas. In addition, it is not always the best candidate who gets the job, it is often the person who performs best at interview.

Who is well placed to answer the question about what typically goes wrong in a job interview? Employers. Sometimes it’s an HR perspective, but the most important viewpoint is that of a line manager or business owner – in other words, someone whose success depends on a good appointment.

Successive surveys point to a staggeringly obvious fact. Employers keep meeting candidates who have not organised themselves for the interview. This comes through in a number of ways:

- Failure to organise the application – candidates are not sure what CV they used, what forms they have completed, or which job they are applying for.

- Failure to organise research – on the requirements of the job and the nature of the organisation. Candidates just haven’t thought about the employer’s wish list.

- Failure to organise self – presentation, dress, manner, attitude, speaking style. Candidates just haven’t thought enough about the way they will come across.

- Failure to organise evidence – of skills, achievements, failures, high points. Candidates just haven’t thought enough about what they have done.

These four critical areas are all dealt with in depth in the chapters ahead. However, when pressed further, employers often zoom in on one critical factor – evidence.

DIFFERING PERSPECTIVES ON EVIDENCE

Having spent about a quarter of a century training interviewers and nearly as much time debriefing candidates after job interviews, it’s hard not to keep a mental checklist of the things that come up all the time.

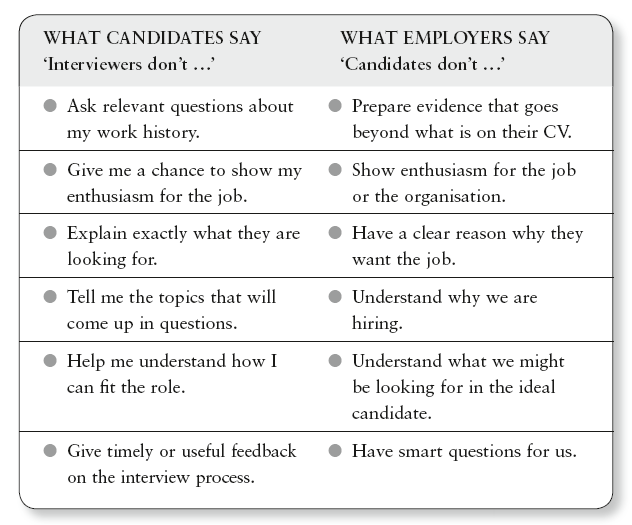

The odd thing is that these change very rarely, even if jobs are scarce or good candidates are hard to find. Employers and candidates tend to say the same things repeatedly, and it’s interesting that they are often two sides of the same coin:

The picture is often mirrored, but there is an important difference between the two. It is an employer’s job to make the interview go well; it is your job to make the interview go well for you. To complain that an interviewer didn’t give you the chance to talk, didn’t want to hear about your achievements or didn’t discover your secret talents is rather like an aggrieved politician complaining that in a TV interview he was asked all the wrong questions. It’s your job to get the key evidence across, whether the question is asked or not.

That may sound unrealistic or feel pushy, but it isn’t – it’s just about recognising that you need to decide from the outset to put in an above-average performance, and to do that you need an above-average mindset. You need to decide in advance that you are not going to make the mistakes that others make, that you are not going to be the kind of ‘problem’ candidate who makes an interviewer’s life difficult. You are going to be the kind of candidate an employer wants to retain, even if there isn’t a job available right now.

THE BASIC EMPLOYER SHORT LIST

Before we get too deep into the candidate mindset, do remember that employers are not terribly sophisticated in their decision making. The US National Association of Colleges and Employers in 2010 published a list of five top skills required by employers (the Association of Graduate Recruiters in the UK has a similar checklist). Where have you demonstrated these skills and qualities?

- Verbal and written communication skills

- Strong work ethic

- Teamwork skills

- Analytical skills

- Initiative.

Employers surveyed also valued interpersonal skills, flexibility and adaptability, computer and organisational skills. The interesting thing is that employers still feel the need, even in a recession, to spell out these basic requirements. It cannot be the case that candidates do not possess most of these qualities. It is far more likely that they do not know how to communicate them.

I GET THE INTERVIEWS BUT NOT THE JOB

It’s a common problem. There are individuals out there who do brilliantly on paper, nearly always get short listed, but don’t seem to get the right results. Many candidates never get beyond an uncomfortably formal exchange of information. They make every answer sound pre-rehearsed, and not always exactly related to the question. At the end, the interviewer feels like an information download has occurred, but it hasn’t felt in any sense like a conversation.

Make a clear distinction between wild shots and likely hits. Random applications for jobs you have little to offer will always give you random and confusing results. However, if you are genuinely getting interviews for the sort of job you could do well, where you really do have relevant skills, qualifications and motivation, and you are constantly getting rejection letters (Chapter 19 tackles this topic in depth), you need to think about doing something differently. Notice that phrase: think about doing something differently. As outlined above, this doesn’t mean a complete overhaul – small tweaks to your performance may be enough. Starting to think differently means not just doing all the right things, but doing them much more consciously, seeking an edge at every point. Read on to see how.