Essential Skills of Intrapreneurs

You have your culture and infrastructure ready. You might even have received a couple of good ideas from your employees. You and your leadership team have excitedly sponsored some of them, hoping they would drive future businesses. But three months have gone by, and nothing much has happened. Then six months in, your employees tell you they’re still at the initial stage, just clarifying the details. A year later, nothing has been launched. You are, quite rightly, wondering what went wrong. And the answer is usually quite simple: your employees may be passionate but they’re not equipped to be intrapreneurs just yet.

If you are looking to groom intrapreneurial talents, use this chapter as a guide to developing your people. Learn the basic concepts of the required skills and understand how they will help your organization innovate. Evaluate your list of potential intrapreneurs, which you identified in Chapter 3, against the list of skills in this chapter. See where the gaps are and explore how you can help your intrapreneurs acquire those skills. You can also use this chapter to review whether or not you have the skills to innovate for your organization. See which skills are new to you and how you can upskill to lead the organization by example.

The breadth and depth of skills required by employees vary over time. Traditionally in large corporations, employees specialize in one domain and work on a set of predefined tasks throughout their careers. The early twentieth-century work system was designed to maximize productivity. It made employees experts in a particular area and little beyond that. This group of employees is called the “I-shaped talents,” with the vertical part of the letter “I” representing their depth of domain expertise. In an article published in Harvard Business Review in 2001, Hansen and Oetinger introduced the T-shaped manager.1 This is a new kind of executive who breaks out of the traditional corporate hierarchy to share knowledge freely across the organization (the horizontal part of the T) while remaining fiercely committed to individual business unit performance (the vertical part).

In 2013, Tom Wessel, author at SolutionsIQ, suggested that as the team matures, the next evolution is Pi-shaped. According to Wessel, Pi-shaped makes an excellent metaphor for truly adaptive team members. Rather than one area of expertise, a Pi-shaped team member possesses two. But now, with rapid technological advancement and the changing market landscape in the era of Industry 5.0, it is time to move on from Pi-shaped talent. Dr. Esin Akay refers to comb-shaped talents—employees whose skills are broad but with multiple areas of expertise in the shape of a comb.2 These multiple expertise areas might never be deep enough as the knowledge of a truly deep specialist is only in one area. However, this is not a disadvantage considering the interconnected and interdependent world that we live in. Comb-shaped talents are agile, lifelong learners and they collaborate with others by having sufficient depth in several domains. Figure 7.1 illustrates how the I-, T-, Pi-, and comb-shaped talents are different in terms of breath and depth of knowledge.

To become intrapreneurs, employees need to develop themselves as comb-shaped talents. In terms of depth, they need to adapt and swiftly learn domain expertise based on the ideas that they are working on. In terms of breadth, they should develop broad business knowledge to enhance how they lead the team to commercialize the idea. Comb-shaped talents truly differentiate themselves by their ability to learn fast and adapt to various settings.

Being intrapreneurial starts with one’s mindset but mindset alone is not sufficient for coming up with a great idea and making that idea a reality in a large organization. In the rest of this chapter, we will talk about the various skills an intrapreneur needs to master. Depending on the domain areas that you are innovating in, the subject matter will differ. For example, if you are working for a logistics company and looking into ideas for automated goods tracking, an intrapreneur might need IoT device knowledge. Those in the banking industry exploring instant, cross-border payments might need to study blockchain technology. What you need to learn in the form of vertical expertise depends on your field, the current applications, and the relevant technology trends.

Figure 7.1 I-, T-, Pi-, and comb-shaped talents

That said, there are fundamental skills that every intrapreneur should develop, which apply across industries and domains. There are four broad categories of essential skills:

1. Disciplined innovation process. A set of skills and methodologies that you need to acquire and learn to identify problems, come up with ideas, and validate and convert ideas into a profitable business. It also includes skills that help you build a bridge between an idea and the actual launch. It helps you organize the project in a structured manner so you and your team have a clear path of execution.

2. Leadership. Skills that you need to inspire, lead without authority, motivate, and collaborate with other people inside and outside of your corporation.

3. Navigating the organization. Skills that you need to navigate a large organization and convince the stakeholders to move your idea forward.

4. Communications. Skills that you need to effectively communicate your ideas with other people.

Figure 7.2 summarizes the essential skills that an intrapreneur needs to master.

Figure 7.2 Four skills that intrapreneurs need to master

Questions for corporate leaders:

• Which talent shape (I-, T-, Pi-, comb-) do the majority of your employees belong to?

• Do your employees possess the skills of intrapreneurs?

In the rest of this chapter, I present the methodologies and tools published by innovation pioneers, my own experience of using them, and how others have used them. An experienced intrapreneur should choose the tools based on the situation, adjust the framework to fit the purpose, and understand what works for the people in their corporation. For further reading about each of these skills, consult the recommended resources in each section.

Disciplined Innovation Process

While creativity requires freedom to grow, innovation requires discipline. Amateurs come up with ideas occasionally, like accidental thoughts. But innovation practitioners who generate numerous ideas rely on disciplined innovation methodologies to spark continuous inspiration. Learn the following innovation methodologies to understand how to generate unlimited ideas, evaluate whether those ideas are good enough, and break down big ideas into new launches.

First, let’s look at the cycles involved in delivering an innovative product. Three innovation methodologies guide you through the cycle, from understanding the problem to launching and scaling a product. The innovation methodologies are:

1. Problem-solving using design thinking

2. Launching minimum viable product (MVP) using lean startup

3. Scaling the product using agile

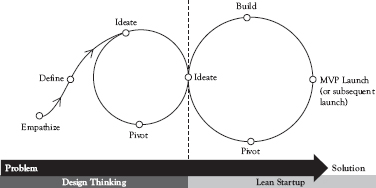

Each methodology addresses different objectives using different tools and techniques. There are also overlapping areas of these methodologies. Combining these innovation methodologies provides a structured framework for you to execute your ideas. Figure 7.3 is a diagram that shows how a combination of design thinking, lean startup, and agile can work together. This figure helps visualize what the cycle of innovation looks like when design thinking and lean startup methodology are combined.

Figure 7.3 Cycle of innovation combining design thinking and lean startup

The execution of innovation projects is often not linear, with one stage ending and another phase starting without overlapping. So corporations should not segregate the phases to be carried out by entirely different teams and design collaboration only at the touchpoints of different phases. The use of different methodologies and activities should be viewed as a continuous and iterative process.

Problem Solving by Design Thinking

Most people know design from graphic design or packaging design, which relates to the appearance of a product. It’s not surprising as these are visual and relatable; we can see and touch the design. Design thinking is something different. It is a process of customer-centric creative problem solving.

People who’ve gone through education and become industrial designers, user experience designers, or user interface designers often practice design thinking. But you do not necessarily need to be trained as a designer. It doesn’t matter whether or not you can sketch, use design software, or speak design language because design thinking is a problem-solving skill. I’ll discuss the approach and the process but it’s just as important to practice it hands-on by applying it to real problems.

The best way to avoid this problem is with the following four-step process: empathize, define, ideate, and validate.

Empathize

Empathy is the ability to emotionally understand what other people feel, to see things from their point of view, and imagine yourself in their place. It is you putting yourself in someone else’s position and feeling what they must be feeling.3 It’s a powerful ability that allows you to connect with different people, even though you might not come from the same background or have not experienced exactly what they have been through. Empathize guides problem solving by first understanding the customer. According to “The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design” by IDEO,4 empathy is a “deep understanding of the problems and realities of the people you are designing for.”

Empathize is an important stage that facilitates subsequent ideation of good product design. Emi Kolawole, editor-in-residence of Stanford University d.school, said, “I can’t come up with any new ideas if all I do is exist in my own life.”5

Questions for intrapreneurs:

• What is your personal experience of empathy toward others?

• When was the last time you applied empathy to your customers?

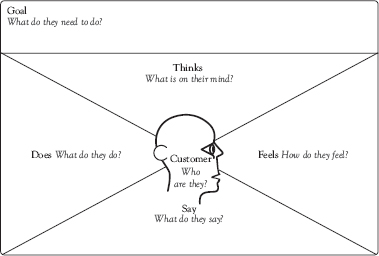

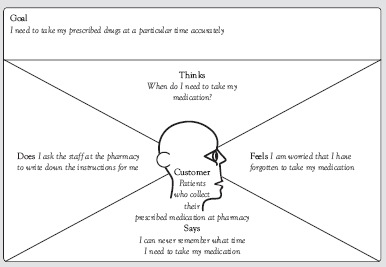

Depending on the problem you are trying to solve, the first step is to visualize your customers’ attitudes and behaviors, bringing them to life on an empathy map. An empathy map allows you and your team to articulate and form a common ground of understanding with customers to discover their needs. Figure 7.4 is a template of an empathy map.

Here’s a step-by-step guide to completing the empathy map:

1. Customer. Profile your customer by giving them a name, age, job, and lifestyle. Build a comprehensive profile by giving more details. The best approach is to profile a real customer that you have dealt with.

2. Goal. What is your customer’s goal? Think of the bigger picture beyond the immediate problem that you are solving. Is the customer thinking about their next promotion, achieving financial freedom, work–life balance, or retirement? This helps you visualize how solving the problem aligns with their prioritized goals.

3. Says. Quote what the customer says during their daily life or your interaction with them. What words does the customer use to describe their problem?

4. Thinks. Capture what the customer is thinking. What is on their mind? What matters to them? What are they thinking but are reluctant to say? Discover why they are hesitant to unveil their real thoughts.

5. Does. What action does the customer take? How did they try to solve it in the past? What alternatives have they tried?

6. Feels. What is the emotional status of the customer? How do they feel about this problem? Are they worried, concerned, excited, or annoyed?

An empathy map is something you can kickstart anytime since it is an early-stage exercise. There are various sources of information that you can bring into it. The team can collectively profile customers by:

• Past customer interaction. If you have direct interaction with customers, you can refer to your experience with them. Quote what they have told you or what you have observed in the past about the issue.

• Sales input. If you do not have direct access to customers, go to a salesperson who owns the customer relationship and seek their help to provide insights. Tell the salesperson that you are working on solving a problem for the customer and will require their help to crystalize the need. Try not to lead the conversation into a discussion of solutions as this is too early.

• Customer service data. Data can be a good tool as they present an unbiased view of what the problem is. You can see how the customer deals with the problem. How many calls or complaints did your company get that are relevant to the problem? What did the customer say when they made the call? Were they emotional about the issue?

• Interview a customer. This is a good source but it needs to be managed with care. It depends on the relationship you have with the customer. If the customer is very open and welcoming, by all means, do it. But if you are not directly handling the relationship or the customer does not have a particularly warm relationship with you, start with your internal resources instead of talking to them. At this stage, since you do not have much to offer in terms of problem definition or solution, the customer could be confused about why you need a conversation.

When you do talk to customers to understand how they view the problem, it is important to differentiate what they say they want versus what they actually need. For that reason, the technique of asking the “5 Whys” can be helpful. The “5 Whys” was originally developed by Sakichi Toyoda and was used within the Toyota Motor Corporation during the evolution of its manufacturing methodologies. It was a critical component of problem-solving training, delivered as part of the induction into the Toyota Production System. Taiichi Ohno, the architect of the Toyota Production System, said that the basis of the approach was to ask “why?” five times whenever we find a problem. By repeating “why?” five times, the nature of the problem, as well as its solution, becomes clear.6 In the context of design thinking, the “5 Whys” are applied similarly but the Whys are asked in such a way as to discover the root desire of the customer.

You should focus on the customer first and not the idea. In fact, this is a common mistake. People are obsessed with ideas that will change the world, and immediately they start thinking about how to make them happen. But once they jump ahead to focus on the solution, they never go back to understand the actual problem or what the customer really wants. Skipping the empathize phase can quickly lead to failure if the final solution can’t help the customer. Or you might end up with a quick fix, catering to a superficial problem but not the customer’s real need. This could make the product weak and you would lose the opportunity to address the problem with a game-changer.

Define

With the insights gathered from the empathize phase, you have sufficient information to proceed to the define phase. Define is a phase in which you synthesize all the information you gathered in the empathize phase. The target outcome is to have a clearly defined and actionable problem statement.

A problem statement defines the unmet need of a customer. The insights you synthesized from the empathy map, and also the “5 Whys,” should be considered when you frame the problem statement. Later on, when you brainstorm solutions in the ideation stage, the solutions should always point to solving the problem you have defined. A clearly defined problem statement keeps the team focused and provides a clear goal and objective.

The format of a problem statement is as follows:

As (the customer), when I (in a scenario/conducting the job to be done), I would like to have (ideal experience), so that I can (achieve my primary goal).

When you form the problem statement, you need to examine it and see whether it fits the following criteria to make it a good problem statement for the subsequent innovation phase.

1. Does it identify the customer? Is there any description of the customer that you are targeting? Are they young graduates? Are they owners of small businesses? Are they working couples with children? Make sure you describe the customer who is experiencing the problem.

2. Does it focus on the need of the customer? The customer’s perspective always comes first under the design thinking methodology. The problem statement should focus on describing the customer’s goal and need, instead of those of your corporation. Try to avoid having your corporation’s perspective in it. For example, a good problem statement should contain wording like “Working couples with children (customers) need a convenient way to prepare for meals so that they can spend more quality time together” instead of “Our company needs to design a convenient way of preparing meals for working couples with children so that we can capture market share and make more profit.”

3. Is it sufficiently broad? Is the scope of the problem broad enough to explore solutions? There is usually more than one way you can solve a problem. The problem statement should not point to one, and only one, solution. It should also not contain a description of the solution itself. However, the problem should not be so broad it has no focus. It is impossible to solve all of the world’s issues using a single problem statement. Try not to include too many problems of different causes.

It’s important to validate the problem statement and pain point. Validation is an important gatekeeping exercise in the design thinking process. Before you proceed to explore the solution, you need to validate whether the problem you have identified is something the customer really wants to be solved. The problem statement you have crafted and the visual presentation of how it works currently is good artifact to start with. Create a simple discussion guide to facilitate the conversation with your customer, building on the information you already have. A simple discussion guide can include questions like:

1. From our research, we have identified the [problem statement]. How do you relate to this statement?

2. Can you walk us through the process the last time you performed this task? How did you feel?

3. From the study, we believe there are some pain points involved. [Visualize the pain points in the as-is scenario.] Which pain point do you relate to?

4. Is there any other pain point that we have missed? Can you describe it?

5. Which pain point(s) is/are the most pressing?

6. How would solving these pain points make you feel?

From the discussion with an engaged customer, you should have sufficient information to validate the problem statement. The bottom line is that your subsequent work should be based on a problem that the customer recognizes as an actual problem, one with enough pain that they want it to be solved now, if not yesterday.

Questions for intrapreneurs:

• From your past experience, do you frame and validate your problem statement before moving on to working on the solution?

• How do you think the technique might help in your upcoming projects?

Ideate

After you have framed and validated the problem statement, it is time to move on to the ideation phase. You will now brainstorm solutions that can solve the problem that’s been defined. Ideation is probably the most exciting part of the design thinking process. It is the stage to set your mind free and explore as many ideas as possible before you land on any. Ideation works better as a group exercise so I would strongly suggest that you form your team (refer to Chapter 8, “Diversity as Multipliers”) or seek relevant stakeholders or allies to brainstorm together. The more ideas you can gather during this stage, the better the results could be. The quantity of ideas matters at the early stage of ideation as you want to capture diverse thinking.

To shift the mindset of the team from focusing on problems, you can make the transition by forming a “How might we…?” statement. A “How might we…” statement looks something like this: “How might we design a solution that can [achieve the goal of the customer described under the problem statement]?”

If I had asked the public what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse.

—Henry Ford, founder of Ford Motor Company

Some people mistake design thinking as hearing what the customer says and providing them with what they asked for. It is, in fact, much deeper than that. The best solution might not be what the client has explicitly asked for or could have imagined. The perfect solution most likely has not yet appeared on the market, since you are still trying to solve the problem. Do not limit yourself only to solutions that you have heard from customers or what other companies are doing. Encourage weird or wild ideas during brainstorming. Do not criticize any idea at this stage. But at the same time, you need to stay away from groupthink at the beginning of the ideation phase. Based on my experience, a good way to arrange ideation without groupthink is as follows:

1. Form a diverse brainstorming group. Gather people of diverse backgrounds and domains in a room for ideation. Try to not have more than half of the people from the same domain. Get everyone in sync on the problem the team is brainstorming. Given them sufficient background in the way of insights drawn from the empathize phase. Provide everyone with the problem statement and the “How might we?” statement.

2. Start with individual brainstorming in silence. Set a time-bound individual exercise during which each person needs to come up with at least five ideas on their own. There should not be any upper limit on the number of ideas. Everyone has to work silently and no conversation among group members is allowed at this stage.

3. Share. Each member takes turns and shares their five ideas. The objective is to allow other members to understand the high-level concept of the solution, not the details. Set a time limit for each team member, for example, five minutes. Ensure everyone has a chance to go through all their ideas. Be open to listening to others’ ideas and try not to interrupt any sharing, debate whether the idea works, or attempt to change anyone’s idea.

4. Synthesize. On a whiteboard, group all similar or relevant ideas together until you have different clusters of ideas. Name each cluster using a broad solution name. Now the group should have several concepts for broad solutions.

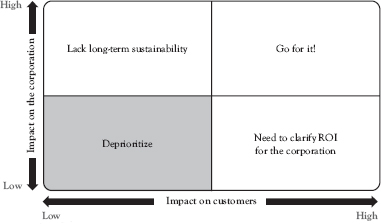

Now that you have those broad-solution concepts, you need to prioritize the solutions to be explored, since you cannot act on all ideas at once with finite resources. When considering which idea to prioritize, you can use the idea prioritization matrix. In the matrix, one axis should be the impact on customers and the other should be the impact on your corporation. Finding the right solution to solve the customer problem is the main objective, but it would be meaningless if it does not benefit your corporation at all. Once you have the matrix up, allow the group to discuss what they think of each idea. Place the idea concepts onto the matrix to visualize where they sit. Figure 7.5 shows a two-by-two matrix that guides leaders and intrapreneurs to prioritize the ideas.

Validate the Idea

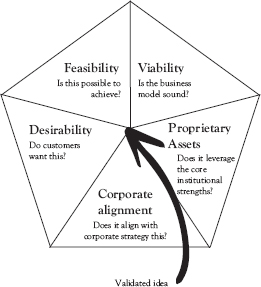

Once you have prioritized an idea, you should proceed to validate it. The idea is still very much a concept at this stage and there is no guarantee that it will work. Certainly, there is no way your corporation would write a half-million-dollar check to invest in an idea based on a high-level concept. To build credibility, you need to validate it from different perspectives by considering three aspects: desirability, feasibility, and viability. A good idea should fulfill all three aspects. Passing it through the lens of validation, you should be able to tell whether a product is wanted by the customer, whether it can be built, and whether it makes commercial sense.

Figure 7.5 Idea prioritization matrix

Desirability, feasibility, and viability are common validations required for any entrepreneur who is launching a new business. However, intrapreneurship demands more. Since intrapreneurs are innovating within a corporate context, corporate strategy and proprietary assets also need to be considered. Let’s go into all of these in more detail. Figure 7.6 shows the sweet spot of a good intrapreneurship idea.

Desirability: Is your idea what your customers desire?

During the empathize phase, you validated the problem. Now you should validate whether the solution you propose is what the customer wants. Usually from the customer’s perspective, it is a question of whether your solution solves the right pain points. A good validation approach is to build a low-fidelity prototype from your idea to share with customers and ask for their feedback. The beauty of a low-fidelity prototype is that it is cheap and fast to make and it can take any form as long as it helps to illustrate your idea. It could be a flow chat, concept presentation, mockup model, wireframes, or some sketched-out screenshots. Plan a discussion guide with a list of questions you want to validate with the customer. Stay open and do not force the solution onto them. Let them tell you what they think works or does not work. Ask the customer whether they consider your solution to be a painkiller that addresses their biggest pain or just a vitamin that eases the issue.

Figure 7.6 Validating an intrapreneurship idea

Feasibility: Is your idea concept possible to achieve?

You can have the most perfect idea and yet it is meaningless if the idea cannot be achieved in the real world. A time machine is a good example! People want it so badly that it keeps appearing in movies and fiction. It is a perfect solution for any regret you have in life. But technology-wise, it just cannot be built. Humanity cannot yet bring the solution to life. So a good idea needs to be possible and work as promised. Are the capability and technology that the idea relies on mature enough, and do they even exist? To test whether the idea can be developed, conduct a proof of concept. Break down the important components of the idea, for example, front end, back end, logic, platform, and interface, and design experiments to test risky assumptions around those components.

Viability: Can you build a viable business model from the idea?

After you have validated that customers do want your idea and it is achievable, the next important question is whether you can make a commercial case. It does not matter how good your solution is if customers do not want to pay for it or if the price is not sufficient to cover the costs of building and maintaining it. Validating viability can be challenging when your solution does not exist today. But you can estimate what the solution is worth. One approach is to look into whether customers are already paying for this problem to be solved. If there are alternative solutions in the market today, check out their cost. See how they compare with your idea. Hopefully, your idea is better than the existing ones (and it should be) and you can use the price as a baseline and charge a premium. However, this baseline approach might not be for the best if your solution really offers a best-in-class experience. That is, it’s a true painkiller compared to all existing solutions. Benchmarking with those for pricing might not reflect its true value. Plus, if you are working on a problem with limited existing solutions, the benchmark might not be accurate. In that case, you can find out what it really costs your customers today for not solving the problem. How much time and effort are they spending? How many people do they hire to handle the current problem? These are more accurate factors that enable you to quantify the price your customers are paying.

Corporate alignment: Does your idea align with your corporate strategy?

As an intrapreneur, you are innovating within a corporation. Eventually, you hope that your idea will become a new product, a new solution, or even a new business for your corporation. Therefore, you should seek alignment with the corporate strategy. That would include the problem that you are working on, the customers you are targeting, and the ideas that you explore. Imagine if you are working in a food and beverage company that operates a fast-food chain as its sole business. But you discover a problem in the pharmaceutical industry that you are passionate about working on. Clearly, the target customers are entirely different from the fast-food customers. Your idea is to launch a new pharmaceutical business. I am not saying it’s absolutely impossible. But it would be rare for a food and beverage corporation to take such a big risk if it is not already in the strategic plan. So look at the strategic plan that your corporation has for the next three to five years and see where your idea might sit in that plan. It will help tremendously when you pitch the idea to management.

Proprietary assets: Does your idea leverage core institutional strengths?

Each corporation has its core strengths and proprietary assets, which are exhibited in its technological know-how, patents, operational model, branding, clientele, financials, partnerships, and so on. Does your idea build on the strengths and assets of your corporation? How much does it rely on existing strengths or does it require an entirely new build? It is more sensible to sponsor an idea that can be built using 80 percent of the existing corporate capability and build 20 percent new capability than the other way around. On the other hand, consider how your idea, when accomplished, brings new proprietary assets that complement existing assets. Ask yourself how your idea strengthens your corporation’s competitive advantage.

Intrapreneurship in Action: IBM—Pivoting Into a Design-Led Intrapreneurial Enterprise

In 2012, IBM hired a new CEO, Ginni Rometty. On her second day in post, she told the employees that customer experience would be fundamental to the transformation of IBM.7 Phil Gilbert, head of Design, and Karel Vredenburg, director of Design, were given a mission by Ginni to create a global sustainable culture of design and design thinking. Before joining IBM, Phil worked for Lombardi, a company IBM acquired in 2009. According to Karel, Lombardi did not have any technology that was new to IBM but it did have an awesome way of designing it. Phil also created a version of design thinking for large enterprises.

With the mission defined by Ginni, the question the team had was how could they make that happen in an organization with 380,000 employees? Karel and his team took on the challenge. Given the scale of IBM, the transformation was a multiyear mission. At the time, IBM had about 200 designers. In the space of five years, it hired designers in the fields of visual design, user experience, industrial design, and design research. By 2017, it had about 1,600 designers and 44 design studios around the world. Phil and Karel scaled design thinking across product, service, sales, and human resources functions. They built a design-led culture by focusing on user outcomes and building diverse and empowered teams.

Design thinking changed the way people approach problems at IBM. Using design thinking, IBM teams are able to build solutions from the users’ perspective and create truly differentiating value for those solutions. To make the transformation sustainable, a special program was created. Employees were provided with tools, best practices, and a community that enabled them to study for an IBM design thinking badge. The plan has been a great success. In 2013, just seven teams obtained design thinking badges. By 2017, over 100,000 employees and hundreds of teams achieved this accolade.

Launching MVP by Lean Startup

Now that you have an idea you believe can solve the problem, it’s time to put it into development. Some product ideas are huge and challenging to pull off. If your idea is big, there could be a lot of components you need to take care of. It is wonderful to imagine that your idea solves everything but we all know that, in reality, it cannot. And for you to execute the idea, you would not be able to deliver all the features in one go. It is simply impossible given the limited time and resources. If you choose to launch only when all the features are ready, you’ll end up delivering the product two years from now and the market demand will already have shifted.

The more sensible way is to think big and start small. You should plan to deliver a good-enough product in a quick turnaround time, hit the market, gather learnings, and revise your offering accordingly. To achieve that, you need to define your MVP, which includes a subset of all the features of your ultimate product. In his book The Lean Startup, Eric Ries defined the MVP as a “version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort.”8 A good example of MVP is LinkedIn. LinkedIn was first launched in May 2003. At that time, it had only the basic features of user profiles and a search function to help people find other users and send e-mail requests. Looking at the interface, it was nothing fancy.

If you’re not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you’ve launched too late.

—Reid Hoffman, cofounder of LinkedIn

The purpose of the MVP is to:

• Build a good-enough product.

• Test your hypothesis and assumptions.

• Gather learnings from the market.

• Use the learnings to pivot.

• Help plan the next launch.

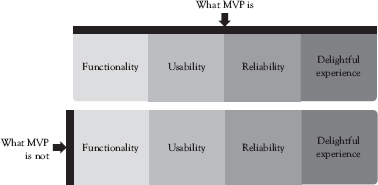

Even though the MVP is a good-enough version, it should NOT be:

• An incomplete product that does not serve its purpose

• A semifinished product

• A broken experience

As you can see in Figure 7.7, an MVP should offer some elements of functionality, usability, reliability, and a delightful experience. If an MVP has none of those things, you need to go back to the drawing board. The figure illustrates what an MVP is and is not.

Figure 7.7 What an MVP is and what it is not

When I worked in a digital banking department, I was designing an instant loan platform for small e-commerce businesses. Traditionally, when the owner of an e-commerce business wants to obtain a loan, they contact a relationship manager. The relationship manager asks them to supply paper documents (e.g., incorporation certificate, financial reports from the last three years) to evaluate the business viability and profitability. They then decide whether or not the customer should be granted a loan and how much the loan amount should be. The problem for the customer was that the process was manual and time-consuming. The customer needed to meet the relationship manager, deal with all the paperwork, and typically wait one month from the initiation of the request to get money in their account. Second, 70 percent of small e-commerce businesses are only one or two years old and would not have three years’ worth of financial reports. What they did have to provide evidence of their business records were transactions on the e-commerce platform. But the bank’s risk assessment process was rather rigid and it did not have a risk-assessment algorithm to process these transaction data. At that time, my team’s idea was to provide a digital platform via which small business owners could submit loan applications based on their transactions. They would obtain instant results on the application and get the loan disbursed in their bank account within 24 hours.

Our team started to break down the components into two large categories: a digital experience and a reliable underwriting algorithm. We presented the solution idea and, since the bank did not have an algorithm that could process data other than historical financial reports, we suggested partnering with an external financial technology provider. Our team’s suggestion was to build an MVP that would provide enough of a digital experience to the customer. It would include an algorithm that would manage the percentage of bad loans under a percentage similar to the current small business loan portfolio.

The plan was to test it for six months and evaluate the pilot result. The management team was relatively risk-averse and very concerned about the algorithm, even though there was a contractual clause that protected the bank, including the cosharing of loss and a guarantee from the FinTech to absorb losses beyond the agreed level. The decision was to pilot the algorithm first and since digital experience is relatively easy to build, it would be catered for in the next phase. The pilot was constructed in such a way that the customer would fill in a simplified, physical application form and submit it with three months’ worth of historical data downloaded from the e-commerce site. The result of the loan application would be available in one week. If approved, the loan would be disbursed to them within one day. It shortened the turnaround time from four weeks to just one. Does that sound good enough?

What we did not know was that we were heading for a total failure. Some 12 weeks into the pilot, we’d only received a handful of applications. The response rate from customers was extremely low. Even customers who had applied once never returned. We were devastated and the management questioned the market demand for such a product. We decided to talk to customers to find out why.

We approached some customers who were offered the pilot but did not make a submission. We sat them down in a focus group and asked them why. One customer asked us, “If you are still asking me to fill in a form, what is the difference from the old application method?” Another customer said, “I am operating an e-commerce site and you expect me to download the data in a paper format? Why wouldn’t you have a digital way of getting my data?” We tried to explain that we set out to test the algorithm first and in the next phase, include the digital experience. The customer replied, “The one thing that I wanted from this product was to get an instant loan digitally. Did your algorithm test help me with that?”

We were embarrassed to hear these comments but they spoke the truth. When we defined our MVP in this project, we focused too much on what we, as the bank, wanted to test, instead of what our customers needed. The MVP was broken and did not live up to the vision we had set. In short, we’d made a huge mistake in coming up with an MVP that did not meet the expectations of customers. When we rethought what the customers actually wanted, it was just a simple way of applying for a loan that gave them instant approval and money in the bank.

Shortly after the meeting, we called off the pilot. We went back to the whiteboard and revised the MVP definition. We made it an end-to-end digital process for customers with minimal core features including an application page, back-end algorithm, and result page. We relaunched another MVP version one month later and it was a hit.

Remember that each MVP launch is a learning opportunity. It is, of course, a win if your MVP hits the ground running and receives good feedback. But even if it does not work, try to understand why from your customers and improve your offering. This is what the MVP is designed for—launch and learn.

How to Define Your MVP

To define your MVP, you can start by breaking down the big idea into components. Combined with the validation results you have obtained in the problem-solving phase, you should be able to prioritize the components of your MVP. Here is a four-step guide on how you can define your MVP:

1. Referring to your customer journey, what are your customer’s goals?

2. List their pain points by the level of pain.

3. Using 1 and 2 above as a reference and the 2×2 MVP features prior-itization matrix later, layout the proposed features based on the level of impact and urgency.

4. Prioritize the features.

Figure 7.8 provides a framework for intrapreneurs to prioritize features for an MVP.

MVP launch is not about building the perfect version but it should provide a good-enough solution that addresses the customer pain points. For backend operations, it might be challenging to have all functions fully developed and integrated for the first launch. As long as it is assembled in a way that the key functions are fulfilled and it does not jeopardize the customer experience, it is a go. Remember, you can always get feedback and pivot after you launch the MVP.

Figure 7.8 MVP features prioritization matrix

Intrapreneurship in Action: Defining MVP of PillPack

To illustrate how MVP and design thinking can be applied in solving a problem and building a product, let’s look at an example focused on a pharmacy problem. The example demonstrates how the methodology helps progress the idea in each phase. This is a real-use case, while some of the information that describes how the methodologies are applied is based on my interpretation as a practitioner.

Background

TJ Parker worked at his parent’s pharmacy when he was a teenager. Patients would visit the pharmacy with prescriptions from their doctors.9

There were usually long queues inside the pharmacy as most patients needed to visit physically to get the medication. TJ would help pack or refill the medication for the patients according to their prescription.

Empathize

TJ observed that various types of medication were prescribed, each with different consumption frequencies (e.g., twice a week, three times a week, taken in the morning, and taken after lunch). To help customers remember when to take their pills, TJ would write on the medication bottles. But to check whether they needed to take a medicine at a particular time, the patients had to go through every bottle to confirm. It was time-consuming and made the patients insecure.

Using TJ’s observation, here is a sample of a patient’s empathy map. Figure 7.9 attempts to mock up the empathy map of PillPack target customers.

Building Domain Knowledge and Forming the Team

On his journey to solving the problem, TJ trained as a pharmacist, obtaining a Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree from the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences. Despite his strong domain background, TJ did not go solo. He met Elliot, an associate at Founder Collective and cofounder of MIT’s Hacking Medicine program. Elliot was an engineer by training and a passionate advocate of customer-centered health care. TJ and Elliot partnered up and set sail on their journey.

Frame the Problem Statement

Based on the insights gathered from patients in the pharmacies and the empathy map, the problem statement could be something like this:

Figure 7.9 Sample of an empathy map

“As a patient who has to take multiple prescription medications, I want a simple way to keep track of what I should consume at different times.”

Validating the Problem

TJ took what he’d observed and synthesized the problem statement. Then he needed to validate whether the problem was real. Based on his work at the pharmacy, he talked to patients about the issue. On top of that, TJ and Elliot also researched the fact that 30 million U.S. adults (that’s one in 10) take more than five prescription medications a day.10 By gathering customer feedback and macro data, the problem as defined was validated.

Ideate

To start the ideation phase, the conversion of the problem statement into the “How might we?” statement could look like this:

How might we design a solution such that patients who need to obtain or refill their medication based on a prescription from their doctors have a simple way to keep track of what they should consume at different times?

TJ started to brainstorm possible solutions to this problem. The potential ideas included:

• A widget that reminds the patient about the meditation

• An application that reminds patients about the medication and reduces confusion

• A smart pillbox for patients to plan their meditation ahead of time

• Packing the drugs for customers each day and sending them the medication

Some of the ideas got invalidated, including the widget, the reminder application, and the smart pillbox, because the problem was more complex than those solutions could solve. TJ and Elliot decided to focus on building an online pharmacy that delivers drugs to patients in per-dose packets.

Define and Launch the MVP

The online pharmacy was not a small idea to execute. TJ and Elliot had to break down the components of such a huge platform. To make the idea work, bring the best experience to customers, and start the business, you can imagine the numerous features and capabilities the team would have to explore, including:

• User-friendly packaging design

• Automatic medication labeling

• An efficient overnight delivery system

• Powerful software platform that takes care of subscription, logistics, and customer database

TJ and Elliot finally launched the solution, PillPack, in 2013 but it was nothing like the idea described above. TJ mentioned in an interview with Founder Playlist that in the early days of the venture, his team would buy plastic food containers from Chinese distributors and blue decals from a printing shop in Cambridge.11 They would ship 200 or 300 boxes a week and every Wednesday night, the team would spend six hours assembling them. They would manually cut openings into boxes so that patients could pull out the packs when they received them. They launched the product purely to get feedback from customers. That was PillPack’s MVP.

Pivot and Scale Upon MVP Launch

After rounds of pivoting, TJ, Elliot, and their team revised the product based on market feedback and upgraded several capabilities thanks to the investment they’d secured. Today, PillPack offers customers:

• Personalized roll of presorted medications, convenient dispenser, and any other medications that cannot be placed in packets, such as liquids and inhalers.

• Medication label with a picture of each pill and notes on how it should be taken.

• Real-time notifications and an online dashboard for customers to control their shipments, refills, and copays. Customers can also e-mail, text, or call their PillPack pharmacist at any time to ask questions or clarify instructions.

• Best-in-class experience supported by PharmacyOS, a software platform that helps manage each customer’s medications, coordinate refills, and renewals, and ensure that each shipment is sent on time, every time.

PillPack is licensed nationwide in the United States. From its launch in 2013 to 2015, it shipped more than 5 million packets of medication. In 2019, PillPack was acquired by Amazon at a valuation of $753 million.12

Agile Project Management

Intrapreneurs need to learn to manage the execution of ideas. In “Disciplined Innovation,” you gained insights into how to break down big ideas into activities. Next, you need to plan the activities and make progress to push the idea forward. You need to build momentum and execute swiftly. If you are lucky, you might have a partner who is a professional certified project manager on your team to implement the project management approach. If not, there are quick tools and hacks for learning and managing it by yourself.

Traditionally, large corporations use the “waterfall approach” to manage projects. Once the project scope is confirmed, the project manager lays out the tasks from start to finish and assigns owners to execute them. Most workflows are linear and sequential. The waterfall approach is appropriate for large-scale projects with well-defined requirements and expected outcomes of high certainty. Since it involves extensive planning with sequential execution, the room for change in scope is limited and flexibility is low.

For intrapreneurs developing a new solution who want to move quickly, other approaches are required. Agile project management, which breaks down big projects into smaller parts, is more suitable for managing innovation. Agile focuses on constant and frequent deliverables. There is a strong focus on execution via collaboration. You might know agile as an approach for software development but, in fact, it is a methodology and mindset that can be applied across different types of innovation projects. In this section, we will cover the common agile methods and tools that can help you move your project forward. By learning it, you can apply agile to manage the progress of your design thinking and MVP activities.

Moving With Speed Using Sprint

Agile makes progress using a Sprint approach. Sprint is a time-bounded period in which the team sets for themselves to deliver a defined scope of work. Instead of managing a project over six months with 100 tasks, Sprint sets a specific scope of work ranging from one to four weeks. During a Sprint, the team agrees on the key tasks for delivering the relevant results during that period. Once they have completed that particular Sprint, the team comes together to evaluate the outcomes, including what is done, what is not, and what they want to focus on in the upcoming Sprint.

The team can decide how long a Sprint should be. The typical practice is to start on a Monday and end on a Friday. If it is a two-week Sprint, it starts on a Monday and ends on Friday the following week, with a total of 10 workdays in between. Using a Sprint to manage tasks and progress keeps the team focused and provides clarity on the priority of tasks. It also builds momentum for the team since the milestones are set in the near term in a manner that’s achievable. It is not a good idea to have too long a sprint (anything beyond four weeks) as it’s supposed to be fast moving.

Scope-Setting Using Sprint

Scoping is the first step in a Sprint. You and your team need to define the tasks you are onto. To achieve the agreed scope, the team has to collectively determine:

• What is the goal of this Sprint? Validate some key assumptions, test the feasibility of some features, come up with a high-level business model, and so on.

• What are the tasks involved? Based on the goal, what activities do you need in this Sprint?

• What are the target deliverables of each task? Decide what outcomes the team wants to achieve at the end of the Sprint.

• Who can carry out the work? Which team members are available for this Sprint?

• Who should work on what? Based on the skills of the team members, who would lead and/or partner together to complete which task?

Scrum Meeting With Kanban Visual

Setting up regular touchpoints with the team during a Sprint is important as all team members should be aware of any progress and roadblocks. One of the most efficient ways to keep track of the project progress is to set up a 5 to 10 minute standup or scrum meeting with your team, either in-person or virtually. The meeting frequency depends on the maturity of the project, for example, once per week for an early-stage idea or daily for a project in flight. To facilitate the meeting, you can use a Kanban board.

Kanban was developed in the 1940s by Taiichi Ohno, an industrial engineer and businessman working at Toyota Automotive. It was created as a planning system to control and manage work and inventory at every stage of production in an optimum manner.13 A Kanban system takes care of the entire value chain, from sourcing raw materials to manufacturing to delivering the goods to customers. Much later, in 2004, David J. Anderson, a veteran of the software industry, started to apply the Kanban method to the field of information systems and software development. Kanban has since been applied as a method of tracking progress in various types of projects, or basically anything for which you would like to see gradual progress. One of the most commonly used tools of the Kanban method is the Kanban board. I have been using the Kanban board to track project progress and, over time, I have found that the simplest version works the best and can be applied to various types of projects. Figure 7.10 is a template of the Kanban board.

Bring the Kanban board into the meeting to visualize progress. Each meeting should be run in a way that everyone gets the chance to share the following:

1. What have you done?

2. What are you doing?

3. What else do you plan to do?

4. Is there any roadblock that you face?

The primary objective of this standup meeting is to provide a quick update on team activities, not to deep-dive into any task. If there is a roadblock, the team should quickly identify items for action or escalation. Anything that cannot be resolved in this 10-minute meeting should be followed up in a separate setting with the appropriate stakeholders.

Intrapreneurship in Action: Airbnb Team Built Online Experiences in Just 14 Days14

Intrapreneurship plays a critical role in business success, especially during turmoil when a big change is required within a short time. Airbnb was a good example. In 2020, the travel industry was impacted by the pandemic. Borders were closed and travels were restricted to stop the spread of the virus. Businesses in the airline and hospitality industries were at risk. Airbnb’s business, which is dependent on traveling activities, was inevitably affected. One of the products, Experience Worldwide, which offers guests in-person experiences, has experienced a significant decline due to the limitation of in-person activities. The program was put on pause to keep its hosts and guests safe. It does not affect Airbnb alone, but also the hosts who rely on the income generated from the program.

The Experience team who is in charge of the product was on to an urgent task to explore alternative revenue channels. Proactively listening to the hosts, the Experience team has observed the need for a new product for virtual experiences. The team started to collaborate with cross-functional teams including engineering, product, design, content, operations, marketing, and research.

To manage the project in a highly efficient manner, they have used:

• A project kickoff to solicit input from a broad range of stakeholders;

• Daily standups to ensure alignment across teams;

• Project tracker to visualize the work and help identify roadblocks; and

• Extensive testing by launching early and often.

The team has built an end-to-end product called Online Experience in just 14 days. It allowed them to support their host community while continuing to provide the guests with unique opportunities to stay connected during difficult times.

The product was a great success. Hundreds of thousands of guests around the globe have signed up for Online Experience. The initiative has transformed Airbnb’s business model and expanded its business with a new income channel.

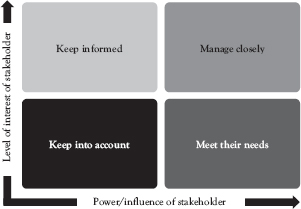

Map Your Internal Stakeholders

To strategize how to push an idea forward, you will need to think about the people in the organization who can support you, as well as those you need to spend the effort to convince if you anticipate pushback. Mapping your internal stakeholders helps you visualize the motivations of different people, their level of interest in your idea, and the role they play in your plan. Start mapping stakeholders right from the start of a project and review it periodically. This is not project material that you would show to your stakeholders. It is a confidential document only to be shared among a small number of core team members. Figure 7.11 is the template of the internal stakeholders map.15

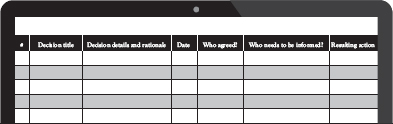

Keep Track of Decisions

A decision log is equally important for managing a big project or an early-stage idea. During the process of exploration, observations and validations result in decisions on which path to pursue. Along the way, more stakeholders come to the table and, based on their feedback or input, the direction of your idea might have changed or been adjusted. You will need to keep track of all those changes and the rationale for the decisions. This is to avoid back and forth arguments or overlooking information after a couple of months when no one remembers what was said and why a particular decision was made. Intrapreneurs should get into good habits by tracking decisions when the idea is in the development phase. The minimum you should do is write up a short minutes document after each meeting, with clear decision points and contributors. These should be shared with everyone involved in the meeting and the project.

Figure 7.12 Decision log template

A recommended approach is to keep a decision log, a document that records all the critical decisions made throughout the exploration of the idea and the project. A well-maintained decision log will help to:

1. Eliminate ambiguity and misunderstanding about a decision.

2. Inform members who are not present in the meeting.

3. Save time recalling who said what and why.

A good decision log should include information describing the issue discussed, the decision made, the time it is made, who agreed to it, the rationale it is based on, and the relevant action item (Figure 7.12). It might only take you two minutes to keep track of each decision. You might find it tedious to diligently maintain such a log but, believe me, you will find it very handy when you need to refer to it.

Leadership

Leadership was very different 20 years ago. With digitalization, technology advancement, and the exponential growth of social media, businesses today are facing a rapid pace of change. Leadership skill requirements have also been evolving. A leader is no longer simply a person who has direct authority over others. In fact, what the world needs today is effective leadership that is more of a mentality than a title. Anyone can lead effectively, even without authority, if they have developed the right skills. Obviously, there are many important skills in the domain of leadership. This section will focus on those that intrapreneurs should develop to achieve success in bringing innovation to their organizations.

Lead by Influence, Not Authority

Leadership is a choice you make rather than a place you sit. In other words, leadership comes from influence and not from your position. For this reason, even when you’re not in front, you’re still leading those around you.

—John Maxwell

As an intrapreneur, you have to collaborate widely with a diverse group of people. Most of those do not report to you. If you are in a senior position, you might be able to flex your muscles and apply your authority. However, that might not work all the time, especially with people who are sitting outside of your reporting verticals. The good news is that intrapreneurs don’t need to rely on authority to lead. Leadership by authority is rigid and is not the best way of encouraging collaboration. People follow authority because they have to, not because they want to.

To lead without authority, you need to work on three things: building trust, seeking alignment, and creating vision.

• Building trust. Build your brand and reputation and let people who have worked with you advocate for you. You can achieve this by (1) delivering excellent quality of work, (2) demonstrating high integrity, and (3) building a sincere relationship with your work partners.

• Seeking alignment. Find the common ground between you and different work partners. Find out your common key performance indicators or how your idea would benefit them. Understand what your stakeholders want and always think of what you can offer them. Refer to “Stakeholders Management” under “Navigating a Large Organization” in this chapter.

• Creating vision. Have a clear vision of what you want to achieve. Apply storytelling to share the purpose of your idea and illustrate how bringing your ideas to life impacts the world and your customers. Refer to “Storytelling” under “Communications” in this chapter.

• What is your leadership style?

• Have you met an influential leader who led without authority in your organization?

Lead Through VUCA

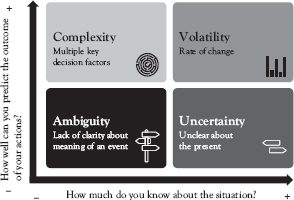

We live in a time of unpredictable changes and a rapid pace of change. Digitalization, Industry 5.0, and the pandemic are just three examples of this. So how can leaders of all kinds navigate an uncontrollable environment such as the one that exists in business today? One tool that has been gaining popularity is called VUCA. The concept of VUCA was coined by the U.S. Army in the 1990s to describe the post–Cold War world at that time in terms of four factors: volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.16

• Volatile (V). Change is rapid and dynamic.

• Uncertain (U). The future is hard to predict.

• Complex (C). Factors for consideration are many and they are interconnected.

• Ambiguous (A). Information is too incomplete to draw any conclusion.

Figure 7.13 Dimensions of VUCA

The importance of leadership through VUCA has been emphasized to entrepreneurs and leaders in large corporations. But intrapreneurs also face their own set of VUCA challenges during the process of innovating for their corporations:

• V: Customer behaviors are changing rapidly. Their expectations are shaped by the experiences brought to them by innovative companies like Facebook, Google, Uber, and Airbnb. The industry that your corporation operates in is likely to have intensified competition from startups and other tech giants that are expanding into the field. Coupled with that, technological advancement is happening at a high speed which makes newer and better solutions more readily available.

• U: No one can predict when your business will be disrupted. There is no guarantee that the competitive advantage your corporation has today will still be there tomorrow. When you work on a new idea, a new market, or a new business model, it’s always uncertain whether or not it will be a success before it is launched.

• C: Navigating a large organization is complex. You will need support from a wide group of people to get it over the line. There are also strategies, risks, and regulations that come into play. Understanding a complex problem in depth is not easy and it requires extensive research to discover the root causes. Building an idea from scratch, deploying technology, and assembling all the pieces are not simple tasks.

• A: You might never have 100 percent of the information before you call for a decision, whether it is deciding which problem to focus on, which idea to explore, or how to form the MVP for the first launch. When your idea goes beyond your corporation’s core competencies or targets a new segment or market, it is hard to have all the data available.

Given all of the aforementioned, intrapreneurs should build on the four areas to successfully navigate VUCA:

• See opportunity in each change. Even the most drastic change brings new opportunities. During the pandemic, a lot of people had to work from home or in a kind of hybrid mode between the office and home. This posed challenges to operating businesses without disruption. Food and Beverages (F&B) and retail businesses have taken a strong hit with lockdowns and social distancing rules. The cessation of traveling impacted airlines, hotels, and travel agencies. The pandemic had a wide adverse impact across various industries, small businesses in particular. In mid-2020, research by McKinsey & Company showed that between 1.4 million and 2.1 million U.S. small businesses could close permanently as a result of the first four months of the pandemic.17 This problem wasn’t just confined to the United States, with businesses in Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa encountering the same issues. However, even in the darkest times, there are opportunities. Amid the slow economic growth, the pandemic led to a surge in e-commerce and accelerated digital transformation. The share of global retail trade for e-commerce rose from 14 percent in 2019 to about 17 percent in 2020.18 Companies operating online delivery, virtual meetings, and digital tools have benefited from the change in consumer behavior. Perhaps the most famous example is Zoom, a video conference tool. Its number of daily users rose from an average of 10 million worldwide in December 2019 to 300 million in April 2020. The company’s share price rose ninefold, from $62 in April 2019 to $559 in December 2020. Volatility provides opportunities. It is not easy to navigate but it offers chances for people who stay on top of trends and are willing to look around for signs.

• Keep up with innovation and technology. The world is uncertain with all of the ongoing changes. To bridge the gap between problem and solution, you need to keep yourself updated with emerging technology trends and innovations in the market. One of the traits of intrapreneurs is constant learning. Thanks to news and social media advancements, access to information is fast and easy. You can keep up with the latest changes by visiting sites like TechCrunch and WIRED, subscribing to innovation newsletters, and listening to podcasts relevant to your industry.

• Move with agility. Agile is mentioned under “Project Management” in this chapter. In fact, agile is more than a project management skill. It is a mindset that you can apply to navigate VUCA. Based on Henna Inam, author of Wired for Disruption, employees need to become catalyst leaders with four types of agilities:19

1. Context-setting agility: You need to scan the environment, anticipate what might change, and frame the context in a compelling way that influences others.

2. Stakeholder agility: You need to identify, seek out, and engage key stakeholders for input and alignment. Stakeholders have both the power to help you succeed or cause you to fail. Knowing the motivation of the stakeholders can help carry you toward your goal. Refer to “Stakeholder Management” under “Navigating a Large Organization”

3. Creative agility: You need multiple views when dealing with a complex problem and to step back to examine the assumptions being made. You need to be able to get in-depth into the problem and yet expand your creativity to try ways of solving it without getting stuck.

4. Self-leadership agility: You need to engage deeply in growing your self-awareness by first envisioning the kind of leader you want to be. There might not be a clear assignment that tasks you with solving the problem. You need to be self-driven and be able to motivate others to partner with you with self-leadership, not assigned leadership.

• Be comfortable making decisions without complete information. During the process of innovation, you will not be able to get all the data before you move on to the next stage. First, always verify the source of information to ensure you are making decisions based on factual and accurate information, even if it is not complete. Second, you need to synthesize all the information on hand and review its implications. Understand which piece of information is missing that you wish to have and analyze how much effort and time are required to find that missing piece. Most often, it is not realistic to wait until the data are complete. In that situation, intrapreneurs need to know how to break down the assumptions behind the decisions and move quickly to test them. Decide what parameters you need to measure to validate whether your decision is the right one and find a way to measure them. These parameters can include customer signup, retention, throughput rate, transaction uptake, and so on, depending on what the decision is. Once a decision is made and executed, observe the outcomes of the parameter in a timely way and respond or pivot if required.

Network Widely and Across Disciplines

Networking is an important skill for entrepreneurs as they venture into the unknown—they cannot be experts on everything and they need to tap into the resources of their network. If anything, networking is even more important for intrapreneurs because office politics comes into play. However, some people are hesitant when it comes to networking. It might seem like they are asking for favors or else they are not comfortable talking to people they don’t know.

In fact, networking is about building relationships. It shows your sincere curiosity about other people. Networking should never start with your desire to get something out of the relationship. It starts with a simple and genuine thought that you are interested in someone else’s story. And when you approach networking outcomes, you should always think first of what you can share or give rather than ask for. People tend to withdraw if your first goal of networking is selling or asking for help.

Many people in corporations view networking as a tool only for job hunting or getting their next assignment. That is, after all, the conventional way people harnessed their network. For intrapreneurs, though, the real impact of networking is far more than that.

How Can Intrapreneurs Benefit From Networking?

• Inspiration. Innovation can happen when you connect the dots across trends in different industries and fields. An application that works in one domain might be transferrable to others. Building a diverse network can help you widen your lens and draw inspiration from interacting with others.

• Domain expertise. Depending on the problem or solution you are working on, you should build a network with people who have a strong understanding of the domain. They have extensive insights based on their first-hand experience of the issues and they might also have made attempts to solve the problem but have not been able to. The sharing of learnings could be invaluable.

• Sponsorship. For an idea to take flight in an organization, intrapreneurs have to seek sponsorship from the management and relevant stakeholders. Networking with them helps you understand what motivates them and how you can better align with their thinking, increasing your chances of getting their support.

• Intrapreneurial rapport. Intrapreneurship is a process that requires persistence to steer through. Having a network of other intrapreneurs, inside or outside of your own organization, can help build a rapport system. You can exchange best practices and learnings along the journey.

Who Should you Build Your Professional Network With?

Networking is an investment of effort and time. Cast your net wide but, at the same time, try to prioritize as you need the energy to build new networks and maintain existing ones. Consider having the list of people below as your networking targets:

• Stakeholders in your corporation

• Other intrapreneurs in your corporation

• Cross-industry innovators or intrapreneurs

• Subject-matter experts

• Startups that are working on similar problems

• People who have experience with the technology you are exploring for the solution

How Do you Build and Expand Your Network?

If you have been working in the same corporation for a long time, you might find your network becomes confined to your own department or team over the years. It is easy to fall into the trap of only connecting with the people you work with. There is nothing wrong with building a strong and deep network with your co-workers. But you might be missing the opportunity to widen your perspective as people who work around you tend to have similar thinking processes and shared knowledge of the same domain. You should try to expand your network. Below are some great places for intrapreneurs to network beyond their team:

• Reconnect with your old network—people who have made a career change or are no longer in your current circle.

• Attend internal town hall and corporate sharing sessions.

• Volunteer for an internal task force or think-tank.

• Attend industry and technology conferences and connect with the speakers and attendees.

• Sign up as a speaker at events to share your knowledge.

• Volunteer at industry events.

• Be a committee member of an industry group.

In my personal experience, I have found that the more you give, the stronger the network you can build from that engagement. An example of a network I benefited from was the internal digital task force for which I volunteered when I was working as a relationship manager in my early career. That was not part of my job scope. The digital task force was formed in the early days of digital transformation and, at that time, I did not know much about technology. It was an unofficial group in which some employees volunteered to imagine and brainstorm ideas that could benefit the future of the bank. By participating in the group, I forged close bonds with people who shared the same passion for digital transformation. With all the knowledge shared among members, I gained insights into exciting trends and learned a lot within a short timeframe. The network carried me a long way and some of the co-workers I met in the group became good friends.

Another example is Women in FinTech Singapore, a networking platform under the Singapore FinTech Association. I have a strong interest in the FinTech scene in Southeast Asia and I started to attend FinTech events when I relocated to Singapore. From the group, I built an extensive network of people working in the field. Later, I decided to become a committee member of the group to drive engagement. The group allowed me to stay close to industry progress and also meet interesting people who widened my horizons.

The main takeaway is that you should find out which professional networks you would like to engage with. If you have an interest in that group, start by participating in events, getting to know the team, and if you are keen, considering whether you can contribute or play a role such as becoming a committee member. If you’re short of time to commit too much, you can still stay close and build your network from it.

Getting Comfortable With Virtual Networking

Since the start of the pandemic, meeting people in person has been challenging. Many industry conferences, seminars, and roundtables have gone online. Besides these events, people have also been shifting their professional networking to virtual settings. Even if our normal, in-person lifestyles resume postpandemic, virtual networking is here to stay. But if you’re facing a challenge building a network remotely, you are not alone. Instead of seeing virtual networking as a second-best option, try to leverage social media and virtual tools. With the help of technology, you can break down geographical and timezone barriers to reach out to people around the world. These are things you can do to build your network virtually:

• Follow groups on social media: Research groups related to specific topics or industries on LinkedIn, Facebook, Clubhouse, Instagram, and so on. Since the start of the pandemic, many industry and technology groups have established a social media presence for marketing. Use keywords to search for the groups’ pages. Start following them and subscribe to their mailing lists to stay on top of updates and events.

• Postevent: When you attend a webinar, roundtable, or conference, make a note of the speakers or panel members with whom you want to connect. If they have shared contact details, you can reach out by sending a note to them. Start by thanking them for their contribution to the event and say that you found the information helpful or inspiring. You can share that you have relevant experience and express your interest in connecting for a further deep dive on the topic. Because you have attended their session and find the topic relevant, the person is more likely to be open to connecting than a cold contact.

• 1-2-1 using LinkedIn: Research people’s profiles on LinkedIn. Identify people you find interesting, who have a similar career, or who are interested in a similar topic. Reach out to them with a note. Your note should be sincere and not too common like “Let’s connect” or “Please add me to your network.” Understand what you have in common, why you want to connect, and how connecting might benefit them. A good example could be: “Hi John, your professional network is very impressive. I am working as/aspire to develop myself as a [role]. Since you’ve been in a similar field, I would like to connect with you and hope we can exchange ideas.” Do understand that LinkedIn outreach is always a probability game. Think how many people you replied to or connected with when you receive an invitation from a cold contact. Do not overthink it. Just do it and if it does not work, simply move on.

Navigating a Large Organization

One of the fundamental differences between an entrepreneur and an intrapreneur is the environment. Entrepreneurs are very much on their own, free to explore what they want to build using their business instincts. Intrapreneurs are, of course, working in large corporations. If navigated well, the corporation offers an excellent platform and resource for the intrapreneur to leverage. On the flip side, it could also create constraints and roadblocks that an entrepreneur in the outside world would never expect to deal with. Let’s take a look at a few of the things intrapreneurs have to deal with.

Stakeholder Management

Entrepreneurs can start working on their own ideas based on their gut feelings or what their business instincts tell them the next big thing might be. They need no permission to start. Of course, the risks they take are high but they have the freedom to explore. This is not the case if you are an intrapreneur. To explore a new idea in a large corporation, you need to convince your stakeholders by finding alignment. You need to make sure what you are exploring is beneficial to your organization and that you are trying to make an impact on the business.

When I worked in the digital department at a regional bank, I met a wonderful mentor, Mok. At that time, Mok was the managing director of the community business portfolio. He was a sincere, humble, and approachable leader. Despite facing constant business challenges and having to stand up to other departments, he always found a way to resolve issues leaving everyone satisfied. He seemed to have the magic touch so I went to seek his advice. He did not lecture me on the topic. Instead, he told a story. That story has certainly changed the way I look at stakeholder management. I will share it with you now.

The Story of the 18th Cow