Chapter 7

Paying the Price of ‘Yes’

Why is the dominant response of many salespeople ‘yes’ when a customer asks for a discount or a lower price? Why is that dominant response so difficult to change?

There are many presumably positive reasons why salespeople make concessions and agree to offer discounts. Discounting can help close a deal quickly, make customers happy, and increase sales volumes and revenue. Discounting can be a very effective tool to counter competitive pressures, whether real or anticipated.

The acceptance of discounting as a useful tactic may also be a halo effect from what salespeople experience as private consumers when they receive discounts, coupons, or free trials.1 The underlying assumption is that if such tactics enhance the personal satisfaction they derive from private purchases, such concessions could engender the same goodwill with customers in a business-related sale. Over time, their own personal experience unwittingly reinforces an urge to respond favourably whenever a client asks for a discount. Hence, salespeople's untrained dominant response is to yield to the natural inclination to say ‘yes’. It will remain their response until they change it consciously.

The studies from Zajonc offer insights into how external conditions can determine how appropriate and how successful the untrained dominant response will be. Whenever the dominant response is the appropriate course of action, it implies that the task is easier or has less at stake. Conversely, if the appropriate response is different from or antithetical to the dominant response – such as when a ‘no’ is required to a request for a lower price – it implies that the task is more difficult. This difficulty may be amplified when the task involves high stakes.

To put it bluntly: when your untrained System 1 response kicks in, it exposes you to too much compromise. The more complex, challenging, or stressful a situation is, the greater the chances are that you will not perform as well, or even screw up the task entirely, with potentially permanent consequences. You end up psyched out, not psyched up.

Scrutiny or observation can artificially boost the amount of stress in a social situation. Psychologists refer to this phenomenon as social facilitation. Imagine what this means for the performance of salespeople working in large corporations, where complexity is the norm. In their sales negotiations, the money and the management fill the role of social facilitation, heightening the pressure and enhancing the effects. There are thousands of dollars at stake for a salesperson in terms of salary, commission, and bonuses. Often millions more are at stake in terms of revenue and profit for the company the salesperson works for. Attempts by the purchasers to impose artificially tight deadlines or otherwise throw off the sales team increase the stress. The buyers are trying to ensure that their request for lower prices will draw a ‘yes’ from the salespeople when the answer should clearly be ‘no’ or at least ‘wait.’

Figure 7.1 shows how these forces apply to such sales negotiation. Think of it as a representation of the factors that can literally make your blood pressure rise. The risk of a bad outcome from a ‘yes’ increases if any of these conditions exist: there is a large financial commitment at stake, the negotiation is complex (perhaps involving multiple products, terms and conditions, timeframes, and business units), or the negotiation is taking place under unexpected or high stress (limited time, team mismatch, limited resources). These factors conspire to trigger a person's dominant response. The decisive question is whether that person will be psyched up or psyched out by these stress factors.

Figure 7.1 The Dominant Response Matrix

There are occasions when the buyer asks for a relatively innocuous concession, such as the waiving of a modest fee. The exchange is only between you and the buyer, the amount is so small that it is almost immaterial to your business, and the decision requires no escalation or additional input from your side. Such situations are most likely in the lower left quadrant of Figure 7.1.

A tense and complex negotiation with your largest key account – under an extreme and unexpected time pressure – could fall into that upper-right quadrant. If the stress, complexity, scrutiny, and potential business impact are all high, then saying ‘yes’ to a discount request in such a negotiation can lead to a disaster with negative consequences that are either permanent or will require tremendous effort to undo. The outcome of that negotiation could have consequences across your company's entire value chain.

A salesperson's immediate ‘yes’ is always a decision that limits or even eliminates their room to manoeuvre. They lose the opportunity to see if everything else makes sense in the current context and to weigh other viable options besides a discount. Having ‘no’ as the dominant response will buy the sales team time to see if a discount might in fact make sense. The team can step back, apply its System 2 judgment, and come back with either a reaffirmation of the ‘no’ or a counterproposal to the discount. Saying ‘no’ also has immediate effects on the purchasing team. One of those effects is to reinforce or re-establish your anchor by drawing attention to it again.

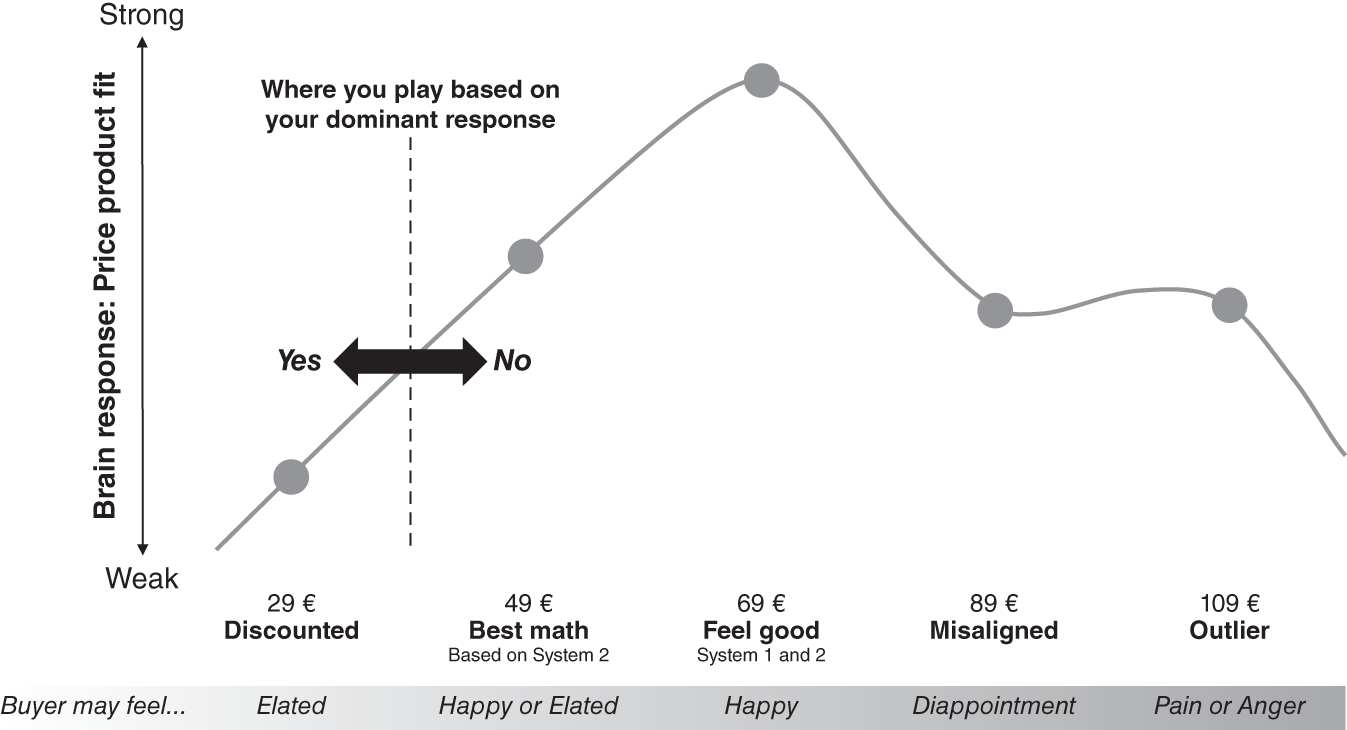

Figure 7.2 If your goal is to achieve the ‘feel-good’ price – the price that matches the most intense response in the buyer's brain – you undermine yourself every time you say ‘yes’ to a discount request

If your goal is to achieve the ‘feel-good’ price, you undermine yourself every time you say ‘yes’ to a discount request. That underscores why ‘no’ should become the dominant response. As Figure 7.2 shows, the dominant response of ‘yes’ causes the team to drift further and further away from the feel-good price.

What homo economicus says about prices and discounts

Why are discounts as risky or even disastrous, as the Dominant Response Matrix in Figure 7.1 shows? To answer this question, we turn briefly to System 2 and its representative, homo economicus.

Mainstream behavioural economics may have declared homo economicus dead, but we prefer to say undead. The ghost of that rational being still haunts the halls of most businesses, pervading everything from strategic planning to price setting. It has plenty to say about the mechanics and consequences of discounting and, from a purely mathematical standpoint, the ghost is correct. So it is worthwhile to review the classical side of discounts before we dive any deeper into more of the behavioural, psychological, and neuroscientific aspects.

Let's start with the textbook role of corporate salespeople. Sales should influence the purchasing decision in such a way that the final choice is their company's desired product at a targeted price. There is no shortage of fancy economic theories and complicated equations – and nowadays, AI-driven algorithms – to help people find the right price. Prices also come in many flavours and forms: target, ceiling, floor, equilibrium, walkaway, average, gross, and net. If you have enough time and enough data, you can find the optimal price by plotting supply, demand, and cost curves and measuring price elasticities by customer segment. That is the conventional view of pricing that you will find in any textbook, university class, or training programme.

Situation 7.1 looks at how that conventional view plays out in a real-life selling situation.

Why it is so hard to say ‘no’ to discounts

Why would people offer discounts when it is indisputable how much financial damage they can do?

There are many explanations for that behaviour. An article in Entrepreneur magazine declared that discounting, ‘is like an addiction. You're going to have to break the negotiating habit cold turkey’.3 Management and pricing specialists typically cite several reasons why salespeople surrender to the pressures to offer a discount.4 The reasons include a bad price and segment structure, a bad value story, poor training, poor management oversight, and a misaligned incentive system. In other words, these experts are alleging that salespeople default to discounts as their dominant response because they lack the right guidance, the right data-driven lines of argument, the right rules, and the right incentives. The absence of these four things creates a powerful vacuum that practically sucks the salesperson down the path of least resistance.

In turn, these presumed rationales for discounting form the basis of the solutions that companies undertake to avoid the dangers of discounts. The common denominator among these solutions is to barricade the path of resistance, or at least clog it up. The thinking is that if the company drowns the salesperson in more facts, applies more force, demands more paperwork, or conducts more oversight, then salespeople will stop giving money away in the form of discounts and lower prices.

Analogous to castle walls in the Middle Ages, these administrative burdens and rules are intended to serve as barriers to protect a company's profit pool from intrusion. These procedures can range from submission forms, to multiple signoffs, to escalation procedures. Some companies implement additional oversight and various combinations of carrots and sticks to cajole salespeople into being arch-defenders of their company's price recommendations, price negotiation guidelines, and bottom lines. These solutions boil down to one thing: impose additional burdens on salespeople, even if they represent ‘non-productive activity that creates an additional administrative burden and imposes a deadweight loss’.5

In the Old Economy, these types of hierarchical and procedural burdens may indeed protect profitability for a company in the short term. That short-term success convinces managers that these tactics are useful ways to ‘solve’ the discount problem, but all they do is address some symptoms of why salespeople discount. They do nothing to address the root cause, and paradoxically, they can even make matters worse.

The last idea we'll discuss from the homo economicus camp, appropriately, involves money. In addition to or instead of imposing burdens, some companies try to change their incentive systems, with the belief that more money is the answer: ‘Incent[ivize] salespeople to sell at a higher price and they will.’6 That seems like the pure definition of a rational trade-off, right? These incentive scheme changes can be blunt and straightforward, such as making commissions inversely proportional to any discounts a salesperson offers. Other such systems are quite elaborate, involving points schemes, but there are numerous studies that cast doubt on the effectiveness of additional money as a means of changing behaviour, especially over the medium and long term.

The reason why companies try to use more facts, more force, and more money to ‘solve’ the discount problem is that they haven't recognized the root cause. Salespeople don't say ‘yes’ to discount requests because they lack enough knowledge, rules, or compensation. They say ‘yes’ because that is their untrained dominant response to the buyers’ questions.

The good news – and the basis for the remaining chapters in Part II – is that behavioural economics, psychology, and neuroscience can enable salespeople to retrain their dominant responses and cure the act of discounting.

Notes

- 1. Wong, D. (2020, February 17). What science says about discounts, promotions and free offers. CM Commerce. https://cm-commerce.com/academy/what-science-says-about-discounts-promotions-and-free-offers/ (accessed 27 May 2022).

- 2. The gross margin of 20% may seem high for many B2B business. The detrimental effects of discounting, however, are even more extreme, if the company's margins were lower.

- 3. Marrs, J. and Kennedy, D. S. (2012, April 30). Is your staff sabotaging your pricing strategy? Entrepreneur. https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/223410 (accessed 27 May 2022).

- 4. reasons why salespeople are quick to discount. (n.d.). Pricing Brew Journal. https://www.pricingbrew.com/insights/5-reasons-why-salespeople-are-quick-to-discount/ (accessed 27 May 2022).

- 5. Simester, D. and Zhang, J. (2014). Why do salespeople spend so much time lobbying for low prices?. Marketing Science 33 (6): 796–808.

- 6. Smith, T.J. (2016, July 3). How to stop discounting practices of salespeople from destroying your profits. Wiglaf Journal. https://wiglafjournal.com/how-to-stop-discounting-practices-of-salespeople-from-destroying-your-profits/ (accessed 27 May 2022).