Chapter 11

Personal Versus Paper Power: Where's Your Leverage?

There is an old sports cliché that underdogs cite after they have beaten a team considered to be superior: ‘That's why we play the games.’1 That cliché also explains why we draw a distinction between personal power and paper power. Paper power – the measure of strength in the Visible Game – relies on tangible factors and arguments that aim to determine which party enjoys an objective advantage. Personal power reflects strength in the Invisible Game. It relies on intangible factors, such as one's ability to influence decision making through frames, choice architectures, and other techniques.

The potential for an uneven balance between personal power and paper power is why sales negotiations still take place. If personal power played no role in a negotiation, then all buying decisions would come down entirely to fact sheets, Excel models, and powerful algorithms. Those objective tools may indicate which competitor is superior and should win the negotiation. But think back to the sales negotiation that Gaby described in the very first story in this book. On paper, Mr Anderson's company should have won that deal. But when the negotiations finished, the underdog Gaby was the one departing New York City with a deal in her briefcase.

Personal power is often potent enough to offset objective advantages that the buyer or another competitor may have. Shifting the balance of personal power in your favour can become the decisive success factor in an intensely competitive market, because it enables you to overcome the advantages conferred by paper power. The balance of personal power is especially important when the differences between any competing offers are slight.

But how do you enhance your personal power so that you can overcome the advantages conferred by paper power? It starts with the ability to assess the balance of personal power before a negotiation and then re-assess it during the negotiation. This often proves difficult, because no party has enough hard information about the other side to make an objective assessment of personal power. The determination, therefore, must derive from situational awareness and from the continuous process of establishing and then validating assumptions. Greater personal power gives a party the leeway to define the frames in a negotiation as well as the terms and the parameters of power in their favour.

One reason why it is vital to assess your balance of power as reliably as possible and project that power effectively is that the buyers are trying to do the same thing. They have the same fears as sellers and are subject to the same illusions and biases. Nobody wants to feel powerless, nor does anyone want the uncertainty of being subject to someone else's whims and decisions. The party who exercises more power controls the path to a decision.

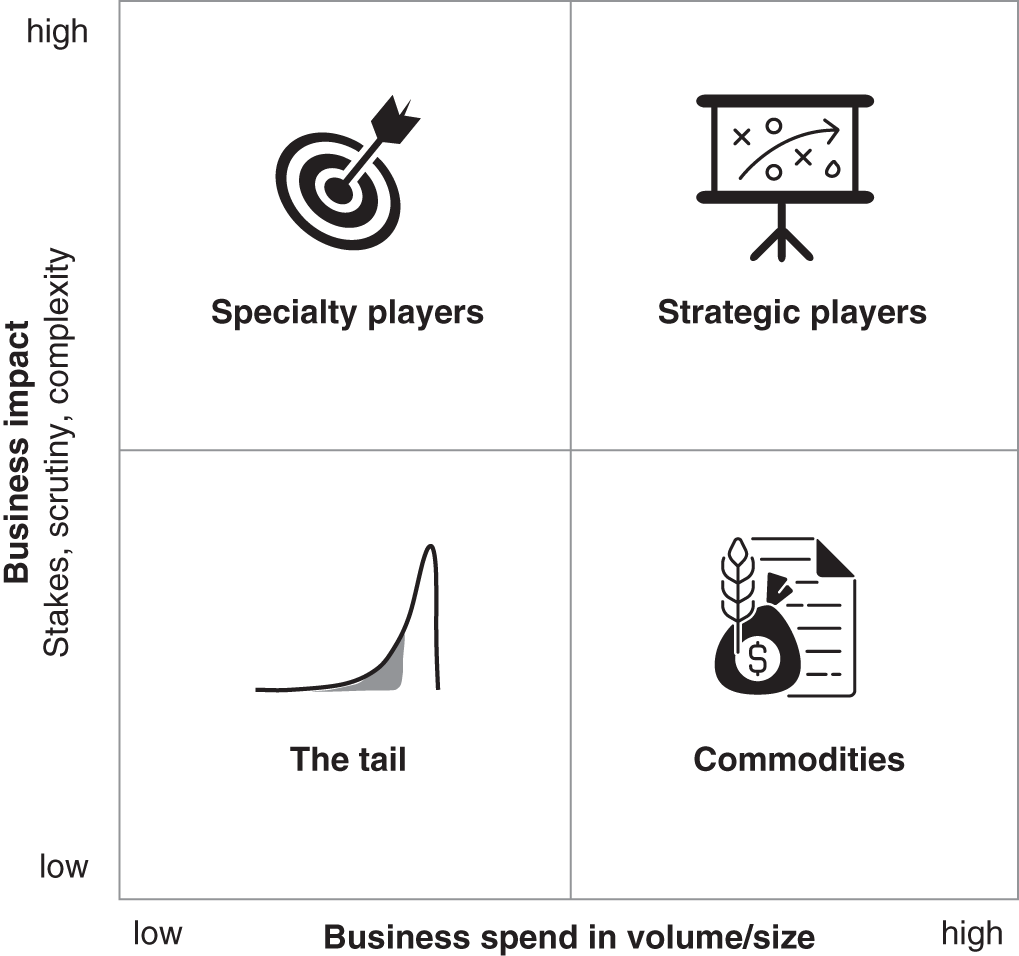

Most suppliers have a customer segmentation, but many fail to realize that their customers have their own supplier segmentations, too. The classic approach that buyers use to determine the overall balance of power between themselves and their suppliers is a segmentation matrix based on an A-B-C analysis and the well-known Pareto rule, along the lines of what is shown in Figure 11.1. This technique has evolved to become a standard approach in the professional buyer's repertoire since a manager from General Electric introduced it 70 years ago.2 For a typical company, around 20% of suppliers account for 80% of their purchasing spend. Around 15% of total spend is classified as medium-risk and the remaining 5% is usually called the tail. For personal power to matter, it is critical for a supplier or seller to be in that top 20% and have a high impact on the buyer's business.

In Figure 11.1, the importance of a supplier is a function of two factors: volume, which one could objectively measure, and impact on the buyer's business, which is more subjective but something that one could estimate with some accuracy.

Figure 11.1 Buyers still rely on the classic A-B-C analysis to decide which suppliers receive the most attention and a larger share of a very scarce resource: their time. The most relevant ‘A’ suppliers are in the buyer's top 20%

The strategic ‘A’ suppliers land in the upper-right quadrant, because they deliver large volumes, have significant impact on the buyer's business, and would be hard to replace because of their specific know-how. The ‘A’ suppliers in the lower-right quadrant still deliver large volumes, but with less overall impact on the buyer's business. They are easier to replace. They might not supply commodities in the purest sense of the term, but the loss or replacement of one of these suppliers would generally not put operations at risk. In such cases, it is difficult if not impossible for personal power to offset paper power.

The ‘B’ suppliers from the upper-left quadrant tend to be smaller versions of the upper-right quadrant ‘A’ suppliers. The ‘C’ suppliers in the lower left typically represent the tail, the large number of small suppliers to be managed with a high level of standardization and little investment of attention or time.

This conventional approach focuses on the present and the recent past. Joseph M. Juran, said to be the first person to apply the 80/20 Pareto rule in a managerial context, once described the role of A-B-C analysis by saying that a company has to distinguish between the ‘vital few’ and the ‘trivial many’ in order to determine how to allocate their time and attention.3

This makes time allocation a valuable indicator for sellers to observe and track. Buyers will try to spend the most time with suppliers that have the highest relevance to their current portfolio. When the risks of making a major mistake are at their lowest – whether in terms of money or quality – buyers will deny time to suppliers and increasingly expose them to transactional ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ behaviours. In some companies, buyers many even outsource such decisions to automated tools.

How customer transformations are changing the balance of power

Analyses such as the conventional A-B-C segmentation played a vital role in the Old Economy, when decisions depended on factors – such as sales volume – that someone could easily measure or estimate. But there is a massive shift underway in the New Economy. Buyers are focusing their attention equally on their suppliers’ current and future capabilities. They still care about the question ‘What can you do for me right now?’ but are replacing ‘What have you done for me lately?’ with the question ‘What can you do for me – and with me – tomorrow?’ The reason is that most companies – and most of your customers – are undergoing significant transformations. Change is everybody's constant, not only yours.

In today's world, no buyer can afford to put their company's future at risk. High-end innovation capabilities are the new Holy Grail for buyers, whose companies are under pressure to introduce their own new products and new models. Buyers are now enhancing their analyses by evaluating their suppliers for their transformation capabilities. Suppliers that are critical to the future success will receive red-carpet treatment.

Figure 11.2 shows how the classic buyer's segmentation matrix changes for companies that are on a journey of transformation.

Your customer strategy, including your pricing, should reflect your status as a supplier. The path to becoming a strategic supplier involves more than high volumes for products with few or no substitutes. To land in the buyer's upper-right quadrant in Figure 11.2 and stay there, a supplier needs to sell their own company's transformation journey and future innovation capabilities at the same time. You need to instil in your customer's organization a belief in a common future, one in which your superior capabilities and agility will make a difference in your customer's success. You need to make your customers dream, because you are a selling them a common future, something that doesn't tangibly exist yet. That requires a well-trained level of personal power.

Figure 11.2 To support their transformation journeys, buyers search for innovation partners with high-end capabilities. They need a supplier classification that emphasizes future capabilities. This changes the role and the importance of personal power

At the same time, you face the risk that at least some, if not all, of your current sales volume might be reallocated to the lower right quadrant. This happens if, in the eyes of your buyer, your portfolio is good for today, but less relevant for their future. Once again, the time a buyer spends with a particular supplier will serve as a valuable indicator for that assessment. You should therefore watch out for changes in buyer's behaviour and be aware of when they start devoting less attention and time to you.

The balance of personal power versus paper power

The more the nature of your relationship progresses toward the top half of Figure 11.2, the more important your personal power becomes. In the top-left quadrant, a supplier may be small, but plays an important role in the buyer's value creation. The place where personal power plays its most important role – significantly outweighing the importance of paper power – is the top-right quadrant. Those suppliers may make a strong contribution to the customer's future through differentiation, ancillary services, and integration within the buyer's value chain, including product co-development. They may also have capabilities the buyer desires to access as part of their innovation or transformation agenda. This is a fundamentally different buyer–seller relationship than in any other quadrant.

In the lower-right quadrant, paper power tends to trump personal power, and you have little or no prospect of tipping the balance. Investing significantly in any form of personal power or building up personal capital is a waste of resources for either party. The best-case effect of personal power will be weak. Switching costs and a supplier's strategic importance tend to be low and objectively measurable, even when volumes are high. Price becomes the most important decision criterion, and there is little room to influence that number through personal power. Your best options are to change the frame by changing the choice architecture or taking advantage of other means to influence decisions, as we will describe in Part III.

Relationships in the lower-right quadrant can quickly develop a transactional character. When that happens, any give-and-take in the relationship must happen within the given transaction. There is no carryover to future transactions. Thus, the chances that personal power will make a difference are minimal or non-existent. In such cases, salespeople should focus on driving a direct quid pro quo and avoid any unsolicited investments (such as discounts or gifts) predicated on the hope that the buyer will remember it and reward it later.

How do you understand your position in the buyer's segmentation?

You need to recreate the buyer's segmentation on your own, as honestly and objectively as possible. This question goes beyond ‘What role do you play for this customer?’ or ‘What value do you add?’ and defines how they classify you internally and what criteria they use to make that classification. This means answering the following questions for every one of your customers.

- How many other options does the buyer have besides you?

- What capabilities do you have that the supplier finds attractive today and tomorrow?

- How important and valuable are you to the customer, both objectively and emotionally?

- What is the source of your real, enduring value?

- Are you hard to work with or easy to work with, in terms of ordering, service, replenishment, complaints, and so forth?

This line of thinking will help you determine whether you are a member of the vital few, the trivial many, or on the cusp between the two. Try to walk a mile in your customer's shoes, as the saying goes. Sometimes givens are not truly givens. The customer might value certain aspects that you or your salespeople might be taking for granted, and conversely, may attach little value to aspects you think are extremely important. Look back into the history between both companies for significant positive events.

If you find out that you have high relevance today but will probably have much less tomorrow, that will obviously be a bitter pill to swallow. All things considered, it is better to plan for obsolescence and focus on other customers than to wake up to obsolescence unprepared.

Let's now assume you have completed these assessments and have determined where your personal power has the strongest leverage. You haven't started to play offence until you have a plan to capitalize on that leverage. The next step in preparing that plan is understanding how buyers make their decisions, which leads us to Chapter 12.

Notes

- 1. O'Conner, P.T. and Kellerman, S. (2018, November 14). The Grammarphobia Blog: That's Why They Play the Game. Grammarphobia. https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2018/11/thats-why-they-play-the-game.html (accessed 28 May 2022).

- 2. The ABC analysis first appeared in an article by General Electric's H. Ford Dickie. (1951, July). ABC inventory analysis shoots for dollars, not pennies. Factory Management and Maintenance 109: 92–94.

- 3. For more information, see https://www.juran.com/blog/a-guide-to-the-pareto-principle-80-20-rule-pareto-analysis/ (accessed 5 August 2022).