Chapter 19

The Power of the Next Small Thing

Coming up with decoys or finding ways to use the power of now to your advantage, for example, may be sexy and creative challenges that people want to be part of. But there are also many small ways to influence the balance of power and change perceptions. These tasks may not come to mind immediately as powerful tactics, but they can help you set and reset frames, now and in the future. We highlight three of them in this chapter.

Restrict the other negotiating party's options

A party's personal power is diminished when something constrains their options or their flexibility. An example of a buyer imposing a power-limiting constraint is to set a deadline. By saying ‘we need a deal by the end of the week’, a buyer instantly leaves the seller with fewer degrees of freedom. Why does restricting options or imposing constraints diminish personal power? The reason is that it creates additional hurdles for the other party to overcome.

Overcoming a hurdle has a depletive effect. You only have so much capacity to deal with hurdles properly. The better way to succeed in a challenging situation is not to overcome hurdles, but to eliminate hurdles and not have them to begin with. Your best opportunity lies in exerting as much control as possible over the environment or frame. The more options you have, the better your chances are to eliminate variables and manage your environment. This is analogous to why we reframed the question of discounting in Part II to make it easier to say ‘no’ rather than harder to say ‘yes’.

Surround yourself with strong allies

A party can enhance its power by cultivating relationships with other powerful parties that will lend their support if necessary. This obviously includes others in your own organization, but can also include business partners along the supply chain to strong outside references. Allies can even include members of the buyer's organization, such as the R&D team, senior executives, or even the buyer's customers.

The dimensions and density of your network matter. Having a strong network within your own organization increases your personal power, both inside your company and in the eyes of your customer. The company VoloMetrix examined the email exchanges of salespeople in a large organization and concluded that ‘having a large and healthy network in your own organization’ is a key success factor, because it enables salespeople to ‘get the right people with the right expertise to the right place at the right time.’1 It also helps salespeople convey a ‘holistic understanding of what their entire company can offer to the buyer above and beyond the current transaction’. When selling the dream, a unified group effort enhances a buyer's perception of the supplier's competencies and capabilities more than any single salesperson could do on their own. Similar to a primate projecting its size in order to look more powerful and avoid a conflict, salespeople can increase their ‘size’ and power by coming across as the spearhead of a larger competent team rather than an individual actor.

Like all other recommendations in this book, there is hard scientific evidence for this. One of Kai's lines of research deals with the Cheerleader Effect and the Banker Effect. The former is well-established and characterizes the phenomenon that individuals in a group picture appear more attractive than when presented alone. The Banker Effect was discovered by Kai and his research colleagues Sonja Lehmann and Romy Eisenbichler. In a controlled online research investigation, the team flashed pictures of people – sometimes as part of a group and sometimes by themselves – to respondents who were asked to evaluate them on various criteria on scales from 0 to 100. They found out that the same individuals shown in a group are perceived to be not only more attractive, but also estimated to earn higher salaries and be slightly more intelligent. The Banker Effect, which indicates successful careers, is not a mere derivative of the Cheerleader Effect, as Lehmann demonstrated in an extensive multivariate analysis. The lesson for salespeople here is that presenting yourself as part of a group – whether in person or on a Zoom call – will enhance your perceived competence.

This is related to network density, which indicates how tightly knit those groups are. One of the more fascinating examples of network density occurs when a smaller company has an ally or friend in a high place within a much larger buyer's organization. This is another manifestation of the Invisible Game. The implicit threat – being able to go up the ladder and call in a favour if something goes wrong – confers power on the smaller party that it could never have on its own. We sometimes refer to this as scandalizing power, because no one on the buying team wants to attract that kind of negative personal attention. A System 1 response kicks in to prevent the buying team from undertaking any steps that could expose them and their careers to unnecessary risks. This is a subtle but important way to use personal power to limit another party's options. By taking certain responses off the table, the buying party is more likely to respond in a way that benefits the sellers. At the same time, the smaller selling party needs to be careful not to overplay its hand. Hollow threats and ‘crying wolf’ will diminish the power that the mere threat of scandalizing power exerts.

Controlling the mundane parts of the Visible Game

The first two sets of actions – restricting the other side's options and surrounding yourself with allies – have more of a strategic nature. They may make the third set of mostly tactical actions look mundane. These actions include setting the agenda, the timing and duration of a meeting, the seating plan within the meeting room, and who writes and distributes the minutes. Given the chance, many people will happily leave that work to the other party, because it's neither sexy nor apparently essential.

Yet that impression is deceptive. Each of these actions can play subtle and powerful roles in projecting power.

Let's look in detail at a few areas that can nudge the entire trajectory of the negotiation in your favour: the agenda and the minutes. These two aspects matter for two overarching reasons. First, any form of communication – but especially one that might travel beyond the people within the core teams on each side – is an opportunity to exercise personal power on something that seems dry, objective, and solely in the domain of paper power. Second, the frame and context – assuming that you own it – can become one of your strongest competitive advantages if you ensure that it lasts beyond the meeting.

The agenda can also determine people's perceptions during the meeting and also affect its outcome and its aftermath. To say that this is ‘expectations management’ is not sufficient, because precisely how you manage those expectations is what makes the difference between setting the frame or obfuscating it and potentially ceding the initiative to the other party.

It is tempting to view this exercise as low value, the kind of drudgery assignment a junior team member might do. It may also be tempting to let the buying team do that ‘grunt work’ so that you can focus on higher value activities. But we see setting a meeting agenda as a vital part of framing a negotiation.

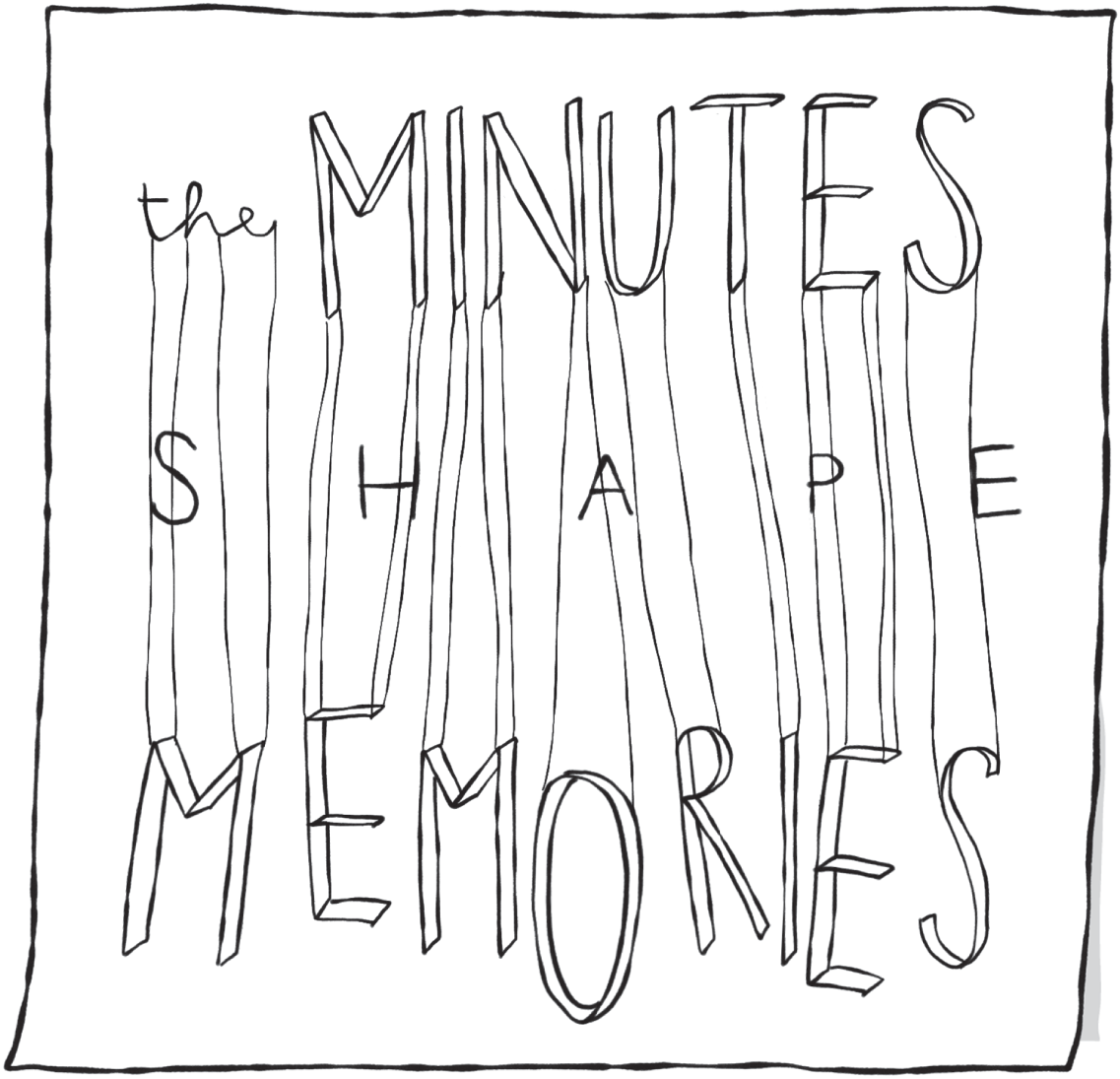

You should also never underestimate the importance and power of writing the minutes. What happens after the meeting can prove to be even more important to enhancing personal power and establishing greater paper power. When your team writes the minutes, you decide what gets circulated outside the group, what information gets kept for future generations, and what information is suppressed or forgotten. This makes writing the minutes a high-value assignment that your team should try to do after every meeting.2

At a minimum, it provides you an opportunity to capture the events of the meeting in the best possible light for your team and company. In the best cases, it can alter the course of a negotiation. It also allows you to inform three audiences about what happened, and do it on your terms. The first audience is the attendees themselves, but that is not as obvious as you might think. You should write the minutes both for the current and future ‘versions’ of the attendees. The attendees may all read the minutes at a later date with a different mindset or different set of needs than they had at the meeting.

The second audience is those people who were not in attendance, including senior executives, managers from other functions such as product development, or even outside investors. The minutes allow them to experience and understand what happened at the meeting. The third audience is the relevant future reader who may not, currently, even be part of your or the buyer's organization. Teams often use meeting minutes to bring new colleagues up to speed, or as a template or benchmark for future negotiations.

The way you express what happened is also important. The minutes are not a dry record that merely expresses the agenda items in past tense with checkmarks. They represent the writer's selective memory and can serve as prompts, similar to the technique of prompts we described in Part II.

Specific words matter, as a study from the late 1970s showed.3 In one landmark study into memory and recall, respondents were asked to view films of automobile accidents, followed by questions about the speed of the cars involved. The question ‘About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?’ led to higher estimates of speed than the question ‘About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?’ One week after seeing the film the respondents returned to answer another 10 questions, which included ‘Did you see any broken glass?’ The verb ‘smashed’ led not only to higher estimates of speed, but also to a higher number of positive responses about whether they had seen any glass. That last point is especially intriguing, because the videos the respondents watched did not show any broken glass.

The experiment demonstrates how leading questions and statements can influence responses. The study's authors also concluded that a complex occurrence leaves two kinds of information in a person's memory. The first is one's own perception of the original event. The second is external information supplied after the fact. Over time, information from both these sources may be integrated in such a way that people are unable to tell which specific detail came from which source.

Practically speaking, this means that writing the minutes is a subjective exercise, not an objective one. The choice of words puts the writer in a powerful position to not only decide what gets recorded, but also how it will be remembered. The minutes help you get people to see what you want them to see when they read between the lines. The meaning of the minutes is greater than the sum of their words.

What the minutes contain, and what they end with, will affect what readers retain. The minutes are a powerful and enduring communications tool. In a world in which people have increasingly short memories and can suffer from information overload, creating a memorable permanent record that people can access later can provide significant leverage to the team that writes the minutes.

Notes

- 1. Fuller, R. (2014, August 20). 3 behaviours that drive successful salespeople. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/08/3-behaviors-that-drive-successful-salespeople (accessed 28 May 2022).

- 2. Rehbock, G. (2022). Hello from the other side! insights 37: 10–11.

- 3. Loftus, E.F. and Palmer, J.C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: an example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior 13 (5): 585–589.