Chapter 2. Each of Us

A bird the size of a leaf Fills the whole lucid evening With his note And flies.

When Individuals Step Up Their Game, the Overall Game Gets Better

At the midpoint in my career, one day I found myself considering a set of difficult questions: What would make me a more valuable contributor? Could I be strategic? What aspects of myself should I cultivate to be the best at what I do? Are there things I could learn to be more influential? How could I make more of a difference?

These questions surfaced shortly after I had won a key argument about how my firm’s marketing department should spend a $2 million budget most effectively to achieve the revenue target. I cared a great deal about how they spent the money, because I was directly accountable for a significant $58 million chunk of revenue (out of $400 million overall).

I was, of course, quite sure that my position on how to spend the money was correct. I had studied the issues carefully, formed airtight arguments that supported my position, and worked the halls to build political alliances. To further increase my chances of winning, I told people why my opponent, the marketing lead, didn’t really “get” the business. And I had no trouble publicly highlighting the flaws in the logic of her arguments and opinions.

In the end, the decision was rendered in my favor and I received grand accolades from the higher ups. I won. I won because I had armed myself with facts and details. I won because I was argumentative enough and persuasive enough to convince stakeholders and decision makers alike that I was right. But at some level I also won by attacking a colleague.

Unfortunately, I did not feel like I had won. I felt hollow. Yes, I had won the battle (as I had many times before), but somehow I didn’t feel triumphant; I felt troubled. Something wasn’t right.

Up to that point, my work experience had led me to the idea that external trappings of leadership were the goal: actionable insights, responsibilities of budget and people, advanced degrees, drive and determination, status, organizational power, title, etc. And after winning that battle, I had more of that stuff than before. Yet I did not enjoy the outcome. Something—some valuable quality—was missing. If it wasn’t missing from the results, then where was it missing? I realized that it was missing from the substance of my being inside this corporation. By “substance of being,” I’m referring to my identity, and to the quality and nature of my interactions with everyone I worked with. In fact, to some degree, I did not really work with many of my colleagues. I worked near them or around them, but not with them. I was not, in a word, collaborative. I worked at being a high-performance individual player, but not a company player.

Before that experience, I had never thought about the choices I was making in terms of who I was and how I would be at work. Until I understood that disappointing win, I didn’t get that how I won mattered a great deal. It turns out that, in this case, it mattered in several ways, and each way became a lesson.

It mattered personally. Remarkably, I already held a core belief in collaboration. But in my striving, I had lost the sense for how that needed to play out within the organization. It sounds trite, but Lesson 1 was that I had been neglecting one of my own values to respect all people, and as a result I had violated that core value. And that’s why I was troubled.

Lesson 2 was that stepping on other people to force the “right” decision contributed to an environment where others did not want to speak up. When the multitudes of voices are stifled or silenced, ideas and initiative get lost. My behavior, along with executive support for it, undermined the sense of safety that lets people take risks inside the organization. My actions were creating the opposite of a collaborative culture. So, even if my spending preference was good for the firm, my style of winning did not benefit the organization.

Did it help me personally? Actually, no. Lesson 3 was that I didn’t benefit in the long run, since many colleagues lost their ability to trust me, which made my job a lot harder after my “victory.”

Each of these lessons is about the way I got what I wanted. I certainly did not aim to be “The Villain” of the story, but I did not know a better way at the time to get the “right” outcome. Like others, I was missing a mental model that would help me see how my behavior helped define a culture that lowered the effectiveness of the whole company. In retrospect, I could see that what each of us does is only part of our contribution. We also need to know how to show up, how to act toward others...in other words, how to be. My internal crisis was about how to excel as an individual while enabling a work environment that would lead the organization as a whole to a bigger success. And this crisis led me to spend the last 10 years reexamining people’s individual roles in business overall and, specifically, in the domain of strategy. This chapter is about how each of us can play a more effective role inside companies.

Perspective Change

Without a change in our individual “how,” a larger organizational shift to collaborative strategy is not possible.

The question becomes, “How does each of us create the most value for ourselves as individuals while enabling value creation for our teams and for the business as a whole?” Each of us, of course, works at creating value at all these levels, and more. Our firms seek to add value to the larger industry, and that industry hopes to add value not just for the shareholders but to society at large. Creating value fuels businesses. It’s why we come to work, because I’m fairly sure most of us don’t get out of bed each morning just to push paperwork around (or win an argument on how a marketing budget is spent). At our best, each one of us comes to work to create and to contribute to the larger whole.

Curiously, I don’t know many people who define success in terms of adding value.[6] Even fewer talk about the personal choices that underlie that definition. Instead, most of us fixate on other indicators as measures of success, starting with GMAT scores, top-10 schools, and graduate degrees. Then it’s where we worked, and to whom we reported or had lunch with. Or it’s our title, or which VC funded our startup at what valuation.

Although we wave these banners as proof of success, they are more symbolic of positional power than of value created. The symbols certainly don’t express the many small, tough choices people make day in and day out that translate into value creation inside a system. Outward symbols don’t measure talent, contribution levels, passion, wisdom, or leadership ability. Titles, degrees, and affiliations might hint at the choices someone has made for how to be at work, but they are not the choices themselves, nor are they indicators or measures of value created.

To be deeply successful, we must recognize how significantly our individual approach impacts the effectiveness of the teams and larger organizations in which we work. This is a fundamental shift in perspective from the plain “what” we do to the richer “what and how” we do work.

Tip

Outward signs (titles, affiliations) don’t measure the choices we’ve made for how to be at work, nor do they indicate value created.

At what time is the how of our work especially important? It is most important during times of stress, when we most need others to share their best ideas to define a new map forward. In short, nowhere is our “what and how” approach more important than when we are collaborating to set direction for the company by creating strategies.

So how do we do this? This chapter is about how each of us can shift our perspective away from an exclusive focus on the “what” of what we do, and include the “how” of how each of us works.

Beyond the Title

Think about your work not in terms of what you do, but in terms of the role you play. Your role is not just your title, but includes sets of behaviors, tools, and approaches to create value for and with your organization. The individual’s role in collaborative strategy demands that each of us learn how to make new choices about who we are going to be at work, regardless of our job title or where we happen to be employed at any given moment. Our assignment is to break the systemic issues we discussed in Chapter 1.

Regardless of your formal title, you play various roles at work. Sometimes it involves leading people and sometimes not. Most leadership books tend to emphasize how to use leadership to improve the way people work. Very few books are written about how we as individuals can improve the way we all work together by altering the little choices we make in how we go about creating and adding value. Despite this gap, most of us have little trouble picturing a model collaborator. We may work with someone like that: the kind of person everyone hopes is on their team. Hardworking, high integrity, curious, easy to get along with, but also able to ask the tough questions and challenge everyone to do their best. It’s easy to think in terms of playing the role of the great team member, but it’s often hard to define the specific actions or behaviors.

I hope this chapter will stimulate a New How for how each of us shows up at work, and about how each of us interacts with our colleagues. My goal here is not to tell you exactly what to do, but to provide a construct; it’s up to you to decide what you want to take in and commit to. So, before you dig in, take a moment and reflect on the following questions. How do I contribute today to the organization’s larger success, independently of my formal title, positional power, or budget authority? Am I enabling the larger organization, and specifically my colleagues, to be successful through my individual way of being?

Do you have your answers to those questions? OK. Then let’s proceed.

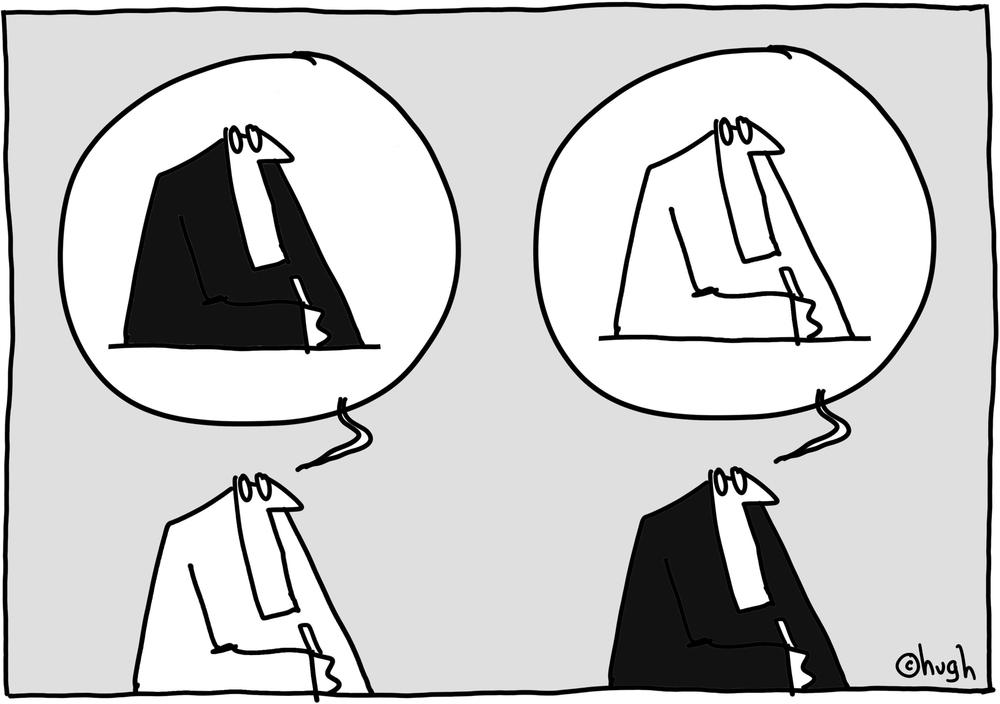

In the quest to consider a new way to engage at work and to become who each of us wants to be professionally, we need to let go of traditional definitions of workplace roles, which are sometimes more troublesome than useful in this area of collaborative work. There is a vast crevasse between people in the role of employee and people in the role of executive in business today. Generally speaking, people in each group view their counterparts as “the other.” Strategy creation and execution missteps generate reactions like “The execs didn’t get the strategy right” or “The employees failed to execute.” This classic us-versus-them dynamic contributes to the Air Sandwich described earlier, where the strategy is based on a clear vision and future direction on the top layer, and day-to-day actions are represented on the bottom, but virtually nothing connects the vision to direction to reality.

This us-versus-them pattern promotes a situation in which both the executives and the employees look for “plausible deniability” of responsibility for any poor results. If things don’t work out as well as they should have, they can just blame “the other” and avoid considering how they themselves might be implicated. And when we struggle to make progress, the divisive us-versus-them battles impede the larger organization from moving forward together and sharing the ownership for creating new strategies.

To counter this us-versus-them dynamic and establish conditions that improve our chances for winning, each of us must get beyond the artificial boundaries that traditional role designations define and reinforce. Do your best to stick those traditional, formal, or organizational labels in some mental cupboard. In place of those confining roles, I suggest that you consider becoming a co-creator.

Each of Us: Co-Creator

Being a co-creator is a new way of characterizing yourself, one that lets you focus on the value you can create, independent of the formal role you have. It gives you a way of morphing from an individual asset limited by organizational hierarchy to a contributor who recognizes that everything you do creates a ripple effect in the organization (Figure 2-1).

As co-creators, each of us takes on a certain amount of additional responsibility for improving the process of creating and executing well-formed strategies. Each of us becomes responsible for co-creating the basis of success. And this is critical, because the business world is moving to a place where creativity drives results and ideas are becoming the core of strategic and competitive advantage.

Once upon a time, some firms had more access to data and information than others. Some firms had more skill at slicing and dicing. In that time, heavy-duty data analysis was enough to form a competitive advantage. Today, everybody has access to vast amounts of high-quality information and the tools to crunch it. What matters now is the ability to act on that information: to conceive—now—the nugget of hidden opportunity in a given situation. The key is being able to work with one another and come up with new ideas, build on those ideas, and then add insights based on the data that empower us to act in unique and differentiated ways.

It’s not as if we used to be robotic “knowledge workers,” copying and collating and answering email, but now any sign of routine activity is going out the door. Given the growing supremacy of ideas, we need a new moniker for individuals at work, one that matches how critical ideas are becoming for the growth and vitality of our companies. This designation is a co-creator. A co-creator is an advocate, a champion, and a lobbyist for the creation, development, and adoption of the best ideas to help the company win. Co-creators work as an important part of the organization, engaging people to create powerful new solutions to tough problems, regardless of their formal roles in the organization.

Fixing the way your company creates strategy and adopting a more inclusive process requires shifting how you participate and act. Each of us has contributed to the situation we find ourselves in today. Each of us has made choices in the past. Perhaps you kept quiet instead of questioning something your boss proposed, or chose not to contribute on a project because it wasn’t your “assigned” role, or held back while others developed strategy because it “wasn’t your responsibility.” Or maybe it wasn’t what you did but how you did it. Did you only half-heartedly suggest an idea that, in fact, you believe in strongly? Did you take a cheap shot at someone else’s idea rather than making a constructive suggestion? What are the results of choices you made in the past? These behaviors likely debilitated the creation of new business solutions. The point here is not to dwell on the past, but rather to recognize that there is room for change.

Tip

A co-creator focuses on advocating, championing, and lobbying for the best idea to help the company to win, regardless of his or her role in an organization.

When we make these poor choices, we are stepping back instead of stepping up. When people lean back, the strategy creation process doesn’t get all the fuel it needs to generate a well-formed strategy that would enable the company to succeed. Critical information about the company’s situation in the market might be missing. Information about the organization’s true capacity is absent. Almost certainly, the resulting strategy would lack some degree of commitment on the part of those who need to implement it.

And that’s got to change. The shift involves two things. The first is your willingness to speak up and give voice to your point of view about what you know to be true. The second is to remember that a decision not to act or not to speak is just that: a decision. It’s when this voice is let out that it can change the outcome. Held quiet, it never has a chance.

Until now, the executive team has owned strategy the noun, and no one has taken ownership of strategizing as the verb. Executives historically have claimed responsibility for setting the direction that produced “the strategy,” and drove a culture that established the Air Sandwich. By not treating strategy as a recurring, progressive process throughout the organization, these executives are encouraging poor business outcomes.

Here is a story about Arthur, the vice president of product management for an $8B consumer products company. Arthur’s story highlights how we can add more value as a co-creator:

Arthur is a very intelligent executive in an interesting situation. Year after year, his company is losing market share and he isn’t doing anything about it. Arthur feels constrained by the expectations that he believes his boss, the CEO, has of him. Arthur’s formal role is to set product direction. The company is facing a set of complex industry trends and dynamics that are making the firm’s products increasingly irrelevant in their current markets. Arthur has a strong gut sense of what the company needs to do to turn the situation around. Arthur is in an ideal position to see what direction the company needs to go and how the company ought to get there. Despite all this, Arthur is sitting on the sidelines.

Interestingly, in private, one-on-one meetings, Arthur will say, “Look, I only have charter for ‘x'—I’m only allowed to do ‘y.’” As a result, Arthur won’t bring up his ideas to the other executives, let alone lobby or champion for them inside the organization to make them actually work, because he doesn’t believe he has that authority.

What should Arthur do? If Arthur can’t drive product strategy, who can?

While none of us wants to see ourself as like Authur, we all do this to some degree. We limit ourselves to what we believe others expect of us (based on our role or job description). So in this way, this chapter is about you: it’s about you being able to champion ideas regardless of any specific role you have, and take on a role to help people see ideas in such a way that they want to act on them. It is about you, not as a “direct report” or as somebody who is a leader of others, but you as a co-creator—of insights, of creativity, of innovation, of contributions to your organization. Let’s go forward recognizing that although coming up with new ideas and being smart is essential, it isn’t enough to succeed. Being smart is just the beginning of being a co-creator. Smarts let you be the champion for the right thing, which is incredibly important. The difference is that you don’t just want to make a smart argument, you want to turn those smarts into a focus on championing for the right solution.

So what will it take for you to become the strongest contributor to strategy creation that you can be? Let me share a secret: it’s not about getting smarter. Sure, strategy frameworks, business models, market knowledge, and domain expertise are essential to strategy creation. But creating great strategy also involves being a good participant in a strategy creation process. And being a good participant is about engaging people in a difficult process, seeing together what matters in a given situation, and together making difficult trade-offs with insight. In other words, becoming the strongest contributor possible involves the set of choices you make in your interactions with others to achieve shared success.

Five Practices for Busting Out

No matter what you do or where you sit in your organization, you are always making choices. You make choices of action and inaction. You make choices about which ideas matter, which ideas you want to champion, when to assert your point of view, and what is worth advocating for the business to consider.

Some choices are about leading people and leading the processes. We’ll cover those kinds of choices in detail in Chapter 3. Right now, let’s look at how each of us can participate in strategy creation as a peer.

We want to achieve two objectives with respect to choices. First, we want to be more thoughtful and less automatic in all our choices, not just the big ones. And second, we want to establish a clear sense of “targeted intentionality”—that is, we need to be aware of the subtle impact on the big picture that we are looking to achieve through the sum of our small and large choices. The tools that we will use to achieve these objectives are embodied in the following five practices. These practices will help raise your level of consciousness about choices that you are already making at work every day. If the practices seem a bit edgy, it is because they are intended to stimulate your thinking as you reimagine ways you can be more influential in how strategy gets created and how you contribute your ideas to the mix. Co-creating is also challenging, and you may find that some of the practices are at the edge of (or even a bit outside) your comfort zone. You may find that you will be expanding your comfort zone as you engage in co-creation. The practices are also designed to help you see the larger impact of your choices.

The five practices are:

Call out

Be fully present

Understand the why

Live in a state of discovery

Embrace contradiction

Let’s explore each of these practices in depth, to start thinking about how using these steps when you do strategy creation in your company will change the culture of work.

Call Out

Often in folklore we hear about powerful magical dragons or beasts we could control if we just knew their names. Calling stuff out within organizations is just like that. When we call things out, we take away their power. Calling out brings issues to light and helps an organization address them. In our role as co-creators, we must fully engage ideas that matter, even when they are unpopular. Co-creators will make choices that demonstrate a bit of boldness as they challenge the status quo by identifying and discussing topics that may have been previously taboo. Such individual choices encourage everyone on the team to participate in a conversation.

Do you see the issues when revenue forecasts are missed? Do you see gaps between divisions where ideas are getting lost? Do you see pertinent information being withheld? This ability to see and—more importantly—to call out what you see is the first thing you can do to start leading change.

Calling out starts with understanding the current state of your organization with as much curiosity and clarity as you can. Your ability to call out depends on your ability to see. Get clear on where your organization has strengths, weakness, blind spots, and patterns that don’t serve the needs of the company. Identify where there are issues that need to be addressed. Find a way to talk about it that is direct and honest, but holds back on judgment or blame. When you call out, you say things like: “I see us addressing only A here and not B” or “It appears the root cause of this issue is X, Y, and Z” or “This issue can be traced back to last year, when we terminated a product line.” Seek to express observations without blame or judgment.

Calling out adds clarity to a discussion. It helps everyone recognize the company’s current state, and gets people to deal with the reality of a situation, instead of what they think is happening or want to believe is happening. When issues go undeclared, then teams, divisions, and even whole companies can spend their time and resources on projects that don’t create value for the organization. Work at seeing these issues, and when you see them, call them out. Be the kid who called out that the emperor wasn’t wearing any clothes. If you have a naked emperor, everybody should know about it.

Here are three recurring scenarios in companies where calling out isn’t happening:

The company fails to acknowledge why customers are defecting, so people work on product features instead of fixing the customer service experience, for example.

The company wishes to defeat the competition, but rather than giving customers the features they need, the company focuses on new technology.

The company does not recognize that a viable alternative to its products or services has entered the market, and continues to raise prices, unaware that their offering is becoming obsolete.

These examples show why calling out is valuable in terms of strategy. Calling things out helps prepare your business for what is around the corner. Despite its value, many seem to avoid it, as though the truth is “distracting” or too scary to think about (Figure 2-2). That’s like driving down a narrow and busy road in the dark: should you turn on your headlights or leave them off?

That said, calling out can be challenging. Have you ever kept your mouth shut in a meeting because you thought you’d be crucified if you dissented from the group norm? Have you held back your opinion because you wanted more time to research the issue? Have you ever agreed to something with the positive belief that somehow your team could figure it out? Calling out takes courage and commitment, because there is always ambiguity. I might be crucified. I’m not sure if research would support me. It’s possible my team can deliver to that aggressive date. In these situations, it’s easier to:

Convince ourselves that others know better (without actually checking)

Focus on only a part (the safe part) of what is there

Keep quiet (even though you’re sure)

All these alternatives to calling out are tactics to avoid pain. Pretending that others know better is an easy way to avoid the responsibility for fixing it. Similarly, when you focus on one part of what exists, you limit your responsibility and risk. After all (you tell yourself), dealing with part of a problem is better than nothing. But only when the full set of issues is known and the choice is explicit.

Working on one piece as a way to avoid issues comes with a risk: you may be solving a symptom instead of the root cause.

Keeping quiet is one of the techniques that all of us use (I’m not immune, either) to avoid extra work or embarrassment. After all, even Abraham Lincoln said: “Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak out and remove all doubt.” He was joking, of course; he didn’t move the nation forward by keeping silent. Nor can we move our companies forward by doing the same.

We adopt these human tendencies to protect ourselves, but consistently avoiding short-term pain is a trap that results in long-term problems. When we make the choice to begin calling out, we are being subtly courageous, taking appropriate action even though we know there is a risk of short-term pain.

Remember that the aim of calling out is not to be negative or critical. It is not about doomsaying or “talking trash,” both of which focus on the negative. Doomsaying dwells unproductively on potentially negative outcomes that have already been raised and considered. Trash-talking is exaggerating the faults of an organization or its products. Neither has any constructive intent, and neither is part of calling out. Calling out is an inherently positive activity, because until your company can identify its issues, the team cannot jointly decide how to respond to it.

As you begin to engage in calling out, you will find many opportunities. Should you leap at every opportunity to declare the unspoken truth? You will need some practice to develop a sense for the best situations and best language to use when calling out. But that skill will only come through exercise. The thing that doesn’t work is avoiding calling out altogether.

Once you see what needs to be solved and name it, the next action you can take to lead change is to begin a dialogue and engage the issues. Did Wonder Woman walk away from the tough stuff? No, she got out her Golden Lasso of Truth and got down to business...and you should, too.

Be Fully Present

Woody Allen said that 80% of success is showing up. What is the other 20%? Fully showing up! Be fully present! Be bold! Show your views. Show your ignorance. Show your worries. Ask “dumb” questions. One of the most important choices you make at work every day—consciously or not—is how you choose to show up!

Many people think they are not supposed to question or weigh in, because they don’t have a certain title, or a certain authority, or a certain level of leadership. None of us needs a designated role to have a point of view. That’s old-school thinking, and it’s totally unhelpful when creating great strategy.

Strategy creation is about understanding, debating, and co-building ideas. Generating great strategies is the creative act of people on a team. Why does that matter? Because if you’re not in the room to advocate, deliberate, and contribute what you have to offer—essentially, to fight over the value of ideas for the benefit of the company—then you and your firm are missing a huge opportunity. Just by saying that you don’t agree, or that you don’t know enough yet, or that you’ve identified conditions that need to be met, your participation is key to making the whole thing work. Without each of us showing up with our best contribution, we cannot change the way strategy gets created. We must show up and engage.

Many people think that they should have an answer before they raise a question. Why? They feel they are expected to “know” something—and sometimes to know everything. Again, why? What is the point of Q & A if everyone is supposed to know the answer? It’s worth a moment to consider also why so many of us feel that asking questions makes us look stupid. Some speakers don’t like questions for various reasons, and try to discourage them. They may also see Q & A as a time for showing off. These speakers may make fun of people who ask questions, which has the side benefit of entertaining others in the room. But, other speakers do a great job of encouraging questions. “That’s an excellent question!”, they will say. How do we respond when we are asked questions? How does our response influence the culture of our firm?

Culture plays a big factor in how we limit ourselves. In the high-tech Silicon Valley culture, being smart is paramount. The implication: looking stupid should be avoided at all costs. If you show up at a dinner party badly dressed and use poor social manners, people may find you eccentric, but VCs won’t be scared off. Even personal hygiene is, ahem, not an absolute requirement. But looking stupid? No, no! God forbid you might look stupid (gasp!). See Figure 2-3.

Now, step back and think about this. Is it really so terrible to look foolish once in a while? It’s not. And it’s certainly better to look dumb and learn than to keep quiet and stay uninformed. If we’re not willing to risk being seen as ignorant by saying “I don’t know” every once in a while, we won’t leave ourselves open to learning. It’s a small act of courage to admit that you have more to learn. And there’s a good chance that others need more information as well. Our ability to learn and grow is the single biggest factor that propels our success. Sure, it’s not fun to look stupid or silly sometimes, but the fear of looking bad can be a major obstacle to your own contribution.

Tip

It’s certainly better to look dumb and learn than to keep quiet and stay uninformed. It’s called the courage to learn.

What about you, personally? What could be blocking you from bringing your all to your work? What would it take for you to say what you actually think? What do you need to do to be fully present in your work? Spend some time on these important questions.

Fear is the main factor that prevents most people from being fully present. Fear is not always a bad thing. It is information, and its value depends on the context and how you react to it. If we always react to fear with a pattern of avoidance, that is very costly. If we treat fear as a signal to pay close attention, then it is very useful. That’s how I try to respond to feelings of fear. When I hear the voice of fear in my head, I stop and listen, because it is telling me there is probably some danger I need to account for in my thinking.

Fear can be a paralyzing force that prevents you from saying what is true for you. Or it can be a clear signal that you need to pay attention to something important. Listen not only to what people are saying, but also pay special attention to the needs or fears underneath their words.

As described in the sidebar "What They Mean to Say" on page 58, it took time to dig through the fear, but underneath it was a valid issue that the whole group needed to hear and consider.

To be fully present means being willing to share everything—your insights, your perspectives, your questions, your worries, and your fears—because you know that your contributions will benefit the group. When we don’t share and reveal with candor what we really need, critically important “stuff” goes underground, which makes it more difficult to consciously manage for optimal business outcomes and often results in unintended consequences. Pushing stuff underground creates the opposite of what we want. To improve our chances of choosing the right strategies and executing them well, we need to share with people why we want or need something. Knowing this lets others help us achieve our intended outcomes in ways that might not be obvious at first. Ultimately, it’s the benefits of transparency and a transparent culture that we aim to enable.

Being fully present and sharing your opinion has the added benefit of giving permission to other participants to show up fully and share as well. It is the opposite of hiding. It is the opposite of keeping your cards close to the vest. Author Virender Kapoor says, “It is not your intelligence quotient (IQ), but your passion quotient (PQ) that will take you to the pinnacle of success.” He’s right, and that’s the essence of being fully present.

When you are fully present, you bring your passion to the table. Learning to bring your passion is instrumental to being a better strategist. Here are some simple ways to practice being present:

Share your needs, desires, ideas, thoughts, questions, and fears with others.

Never discount the power of your voice to influence an outcome, and trust that people will take your concerns seriously.

If you notice that you have withheld something at a meeting, send a note and follow up later. There is always a second chance.

The next not-so-obvious way you can participate in strategy creation is to make sure you know the “why” of a decision.

Understand the Why

Some people feel like they shouldn’t share why decisions are made the way they are. This can include sharing what data was used to inform the decision, which people weighed in, or what risks were considered.

If, say, only a small group of leaders knows why decisions are being made the way they are, it leaves the rest of the organization in the dark. It suggests to people that there’s some “all-powerful wizard” behind the mysterious curtain who is the only one with the ability to make things happen, and that each of us is not a co-creator. It can leave the organizational players believing they have no say in what is being decided. By now, you know these two outcomes are taboo.

Everyone is better off when they know why decisions are made with as much accuracy as possible. It gives them an understanding of what matters and provides information on which to base the trade-offs constantly being made at every level. It also boosts buy-in and energy from the organization. When reasons behind decisions are not shared, the decisions can seem arbitrary and possibly self-serving. That is, they may seem like they are made for the good of the decision makers, rather than the good of the organization.

Tip

When the “why” is unknown, decisions can seem arbitrary and self-serving. When the “why” is known, it raises everyone’s ability to align subdecisions.

We need our people to bring their full brainpower to the game and devise the best ways to get from “here” to “there.” That means sharing data and assumptions freely so you get a full organization of great strategic thinking. You get people knowing what matters, so they know what trade-offs to make to accomplish the goal.

One question that comes up is whether to share contradictory data. I’m a firm believer in transparency, even when the data is not quite aligned to the planned direction. Why? Because if it turns out that something changes in the marketplace, we don’t go all the way back to the core decision, only to realize we had mixed signals early; we just might want to make a 30-degree turn on a decision to adjust. In any case, choosing to withhold contradictory data is tricky, since the people who already know that data will get the sense that the decision makers were in the dark and that the decision was flawed. Again, more informed now equals more aligned later.

Transparency ultimately gives people the power to adjust the aim when needed, and yet stay in full alignment with the larger whole. Transparency from decision makers also encourages transparency elsewhere, so that useful but inconvenient tidbits of information throughout the organization are not swept under the rug.

The good news here is that even if you did nothing other than calling things out, you still would lead change in your organization. To lead more change, you could be fully present, actively leading by example and bringing a new power to your organization. To lead even more change, you can choose to drive organizational transparency. These choices are yours, and that’s an awful lot of power one person can have.

These actions, when combined, provide a solid place to start leading change inside your organization. Remember, Margaret Mead once said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” We are the citizens in the world of our organizations. The kind of change that propels our companies forward can start with each of us, if we choose to be thoughtful and committed. Cultures change not because of some edict from on high, but when all people come together and start to act in a way that others follow. It’s when our way of thinking, being, and doing fills in the Air Sandwich that we start to create more value together.

Live in a State of Discovery

How many times have you made a decision only to realize later on that you had neglected key evidence that was right there in front of you? Why didn’t you see it? Were you bound by your own experiences, a prior way of doing things, a preconceived notion of the way things are?

This is totally human. From time to time, we all find that the way we see the world is limited by unconscious notions of what we believe reality is. But there is a contrasting conscious choice any of us can make: it’s a choice to live in a state of discovery.

Great strategy is at its very core about designing the future, and what it will take to realize that future. If we are not in a state of discovery, we limit the number of possibilities we imagine, invent, and strive for in the future. When we endeavor to live in a state of discovery, we are willing to engage new ideas and revisit assumptions. With practice, we find it easier to let go of earlier ideas to build different ones, and thus tend to be open to the contributions of others. This has an interesting byproduct. When we loosen our grip on our own point of view in order to see others’ points of view, we stop appearing “political” to others.

Living in a state of discovery is an active choice. It means consciously continuing to expand our mental frameworks, and staying open to new knowledge, new insights, and new experiences. I call this “being curious”: being inquisitive about the world, about other people’s points of view, about how things work around you, and even about new notions of yourself. If all that sounds positive and exciting, understand that living in a state of discovery also means being willing to accept facts we don’t like, and being able to see old facts in a new way.

Staying curious and open helps each of us stay mentally agile. By contrast, when we treat our experience, knowledge, or insights as “complete” or “done,” we limit ourselves to the past rather than embracing the future. As long as we restrict incoming data sets, we screen out the good ideas along with the bad. We lose essential information, constricting our ability to invent, reinvent, and create (and co-create) the future.

One common challenge in adopting a state of discovery is learning to listen. That seems obvious, but again we must resist some of our natural instincts to listen well. Listening is particularly hard when we have some perspective or concept that we truly value, a key insight or piece of data that we want to share. In our desire to “express,” we sometimes focus more on outbound flow rather than capturing inbound insights. And we know that if we impress upon those around us that we already know all that needs to happen in creating our future, we leave little room for new options in the collaboration process. The key? A balanced flow of both. We share and we learn.

In the long run, what truly matters is not what each of us knows today, but our ability to continue expanding the aperture of what each of us can see and understand tomorrow. In the short run, any of us can strengthen our skills by learning how to ask good questions.

Living in a state of discovery is an ongoing practice. It is a muscle you can constantly flex, exercise, stretch, and strengthen. By choosing to be curious and accepting of other points of view, you can move from an unconscious preoccupation with your view of reality to being open to new ideas, differing points of view, new scenarios, and unpredicted realities (Figure 2-4). This openness will strengthen relationships and certainly help each of us become a wiser strategist. This is a necessary ingredient in good collaborative strategy creation. In other words, each of us must be willing to set aside the preconceived notions we might have about somebody else, just as we need to stay open to the idea that they might have preconceived notions about us!

Learning to live in a state of discovery can be a challenge, given the day-to-day and moment-to-moment pressure we experience on the job. Here are some straightforward techniques to begin developing this critical skill:

Enter meetings with the intention of asking at least three open-ended questions. These questions should not be about gathering basic facts or about binary issues where a simple “yes” or “no” could suffice, but perhaps about what matters and what is possible. For introverts, some preparation can help them know what they want to explore. For extroverts, it is more about making sure to ask questions that create more learning.

Set a goal for yourself to be in “discovery mode.” There are times in any project where it is clear you need to know more before you even know what questions need to be asked and answered.

Stop silently criticizing yourself and others for not knowing the answer already. Interestingly, really bright people often make it harder on themselves than necessary by judging themselves for not already knowing. Judgment of yourself and others is best curtailed, because it interferes with your ability to be open to learning. To be open to a new reality is to set aside judgment, if only for a while.

Perhaps the most powerful technique for living in a state of discovery is to temporarily suspend passing judgments on seemingly conflicting data, information, opinions, and stories—in short, embrace contradiction.

Embrace Contradiction

One of the toughest things about being a strategist and a co-creator is that almost all of the easy problems have already been solved by the time you arrive. The easy issues involve decisions that are relatively straightforward and linear, with clear cost-benefit trade-offs. This means that the investments and the barriers to action are largely about money and resources. An example might be a run-of-the-mill marketing program where the decision is clear and resources need to be allocated.

Difficult problems, however, occur when you are breaking new ground. Solving such problems requires that both the means and the ends be found. They are often intuitive or holistic decisions where even the process of discovery itself can be transformative. The complexity of these types of decisions usually means they are mired in resistance that borders on open conflict. To solve the problem, the organizations and humans involved will need to change and adapt in some yet-undefined way. A typical strategic decision is a new market entry or an integration of two companies.

Strategy creation for difficult problems, therefore, is incredibly complex by its very nature. It’s rarely clear what the “answer” is, because the problem itself often is not clear. When you roll up your sleeves and dig in, you find a situation of deep complexity where no solution appears ideal. The hallmark of thorny strategy problems is that they involve contradiction—that is, they contain a set of conflicting goals or imperatives that create a tension that defies objective resolution. Either something about the future conflicts with some aspect of the present, or two aspects of the future conflict with each other. If this were not true, the problem would be straightforward. Your intuitive sense for resolution will often differ from someone else’s intuition. And that, of course, is the challenge to arriving at a solution many people can get behind.

Tip

The hallmark of complex problems is paradox.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, one of my all-time favorite authors, wrote a definitive book on Abraham Lincoln and his Cabinet called Team of Rivals (Simon & Schuster). In her book, she characterizes what so many great leaders do when dealing with contradiction. Goodwin states that when Lincoln assumed his presidency, he rounded up his “enemies” and invited them to join his Cabinet. He assembled a team of his adversaries and put them to work for him. At that time, slavery drove the business of agriculture, and agriculture was the engine of the economic growth for much of the country, particularly the South. Abolishing slavery would undercut many people’s livelihoods, changing the economic structure of the country. Depending on a person’s perspective, slavery was either vital or an abomination.

Opponents of the Civil War criticized Lincoln for refusing to compromise on the issue of slavery. Others criticized him for moving too slowly to abolish slavery. Lincoln assembled his political adversaries into his Cabinet knowing he needed their gifts. According to Goodwin, Lincoln, like other great leaders, did not merely tolerate contradictory points of view; he encouraged them. In the end, every single Cabinet member helped to shape post-Civil War America. Today, we all recognize slavery as a cruel human tragedy. But in Lincoln’s time, the issue of slavery was an economic and moral contradiction.

Contradiction is inherent in all decisions involving significant change. When each of us can live with and explore opposing ideas, we create the space to generate more creative solutions than we first thought were possible. At the time of the Civil War, many felt it would be impossible to reconcile our differences and continue as one nation. Yet we were able to change and progress.

To develop as a strategist and co-creator, each of us will eventually internalize the notion that developing good strategy for complex business problems involves opposing ideas living in tension. There is rarely just one right answer when dealing with complex business problems. Those who constantly insist on black and white perspectives will find progress a constant struggle. Don’t just tolerate contradiction; embrace it and work with it.

Learning to embrace contradiction is uncomfortable for most people. That said, it’s richly rewarding because it allows us to take on tough debates and likely uncover tacit issues, and empowers each of us to arrive at a solution that couldn’t be devised without a deep understanding of the situation.

Here are a few techniques to start embracing contradiction:

Notice how much you value certainty versus uncertainty on any given decision, or peace over conflict. There is no right or wrong answer, but you need to know where your natural set point is so you can manage it during strategy creation.

Rate how important certainty or peacemaking is to you, and try increasing your tolerance for uncertainty or conflict in small increments. If you find yourself appeasing people to create peace, you are simply camouflaging the problem and it will only continue to get worse.

Ask yourself, “How could it be possible for both things to be true?”

Without a doubt, learning to embrace contradiction is at the heart of becoming a valuable contributor in the strategy creation process. Refer to Appendix B for more information on dealing with contradiction.

Sitting Forward, Going Forward

We are constantly facing choices in our workplace. On the one hand, we constantly see issues that ought to be addressed today, if not sooner. On the other hand, we are tempted to choose the safety and comfort of checking out and “going with the flow.” Why rock the boat? Why risk being wrong? Why risk a potential conflict? Isn’t it safer to just avoid the risk of being wrong? Wouldn’t keeping quiet be a lot more comfortable than dealing with the issues head-on?

For those of us who seek to do the best thing for our firms, to be strategists and co-creators, the choices are clear, even if they aren’t easy. It might seem safer, more comfortable, and easier to sit back, but we know underneath, it’s actually not. We know that if we do this, we’re depriving the organization of what we know, our insights, and our particular perspective. Our viewpoints can be crucial to helping the company to win. And if the company doesn’t win, none of us wins.

In order to fill in the Air Sandwich, we can’t afford to play only our formal, defined individual roles and neglect what’s going on within the team and the business’s “field of play.”

Adopting the five principles in your individual role is about sitting forward. Sitting forward is a way to meet the world so that you are ready for action—ready to listen, to learn, to connect disparate ideas, to help advance options, to create, and ultimately to make something real. You are engaging with the world, not witnessing it passively. When applied to strategy creation, your involvement is highlighting what’s most important, thus shaping the criteria; making sure the right facts are gathered; weighing in on what will work or not; and ultimately making sure that any potential “gap” between the vision and making that vision a reality gets addressed and closed.

When you make a decision to sit forward, the kinds of problems you deal with may not change, but your appreciation of them will. And, hopefully, through your contribution, others will also appreciate the situation more fully.

This basic stance of collaborative engagement is what drives many people to exhibit great leadership, brilliant thinking, and decisive action. Not surprisingly, these people tend to be very successful. But success doesn’t come from action alone; success comes from a position or a stance, a deeper way of being that consistently creates engaged behavior.

You might find it beneficial to view the apparent problems and challenges in your work life as opportunities to learn something, to make you stronger, to prepare you for something that might happen in the future so you’ll be ready. Although the benefits are not always immediately obvious, when you sit forward and embrace problems instead of avoiding them, you learn and grow, and thus get stronger more quickly.

There is a saying in Eastern philosophy that goes: “If you have a fish in a pond and want it to get big and strong, put a stone in the middle of the pond. The fish will swim around and around the stone trying to get to the other side.”[7] It is in the fish’s nature to explore and move. It is a way of responding to the environment, of being active and present to what can be. Just like the fish, each of us can choose how we respond to our environment. We can choose to be passive in response to the stones in our pond, or we can engage with our environment. One mode definitely changes our relationship to our world and the stance we take when we take on new challenges. One mode makes each of us stronger.

As is evident, we can have a major impact by sitting forward. We can shift how our organizations create strategy today by calling out, being fully present, understanding the why, living in a state of discovery, and embracing the contradiction inherent in complex decisions. Each of us must do our part to find our voice and participate in the chorus of work going on around us. As we do this, we will start to change how we work together.

You’ve likely seen these practices at work in real life. Perhaps not as often as is needed, and maybe not in your current organization, but you’ve seen it. Recall your own experience of when a team is clicking and collaborating, and you’ll see that the members are living out the five practices as a norm. These practices are not inherently hard, but they do require personal strength, finding your voice to contribute as an equal member of a whole, and an intent to co-create the best solutions together.

When each of us contributes in our own way as a co-creator, no single person has to carry the load. Not the exec team. Not some smallish cadre of “strategy leaders.” We each own our piece of responsibility and the load of carrying our part. Having each of us pick up that load and change how we approach work will enable collaboration within organizations to take place systemically.

Those who lead people or projects (in addition to being co-creators) will expect to carry specific responsibilities for enabling how we work together collaboratively. That’s next.