8

Scenario Thinking

What we agree with leaves us inactive, but contradiction makes us productive.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe1

In Chapter Three, we described how Deutsche Post DHL CEO Frank Appel and members of his executive team debated a tough issue over balancing short- versus long-term demands. The question: Should they use year-end cash to show good financial results today or invest for tomorrow? Executives from finance and the company's divisions each represented their stakeholders—shareholders versus customers. They each took a stand to advocate for the silo of their interest. They believed it important to forcefully represent their point of view.

As it turned out, we simplified the story. The executive team members at Deutsche Post DHL faced much more than one paradoxical problem. They faced many of the contradictions that bedevil global corporations today: continuity versus disruption, globalization versus localization, sustainability versus profitability. They wrestled especially over the issue of sustainability. As far-sighted and skilled executives, they asked some interesting questions: What would happen to their company or any company with mass migrations of people, the boom of megacities, changes in disease patterns and severity, the development of new power sources, and other climate-related changes?

We have learned in such situations to use a key tool called scenario thinking. Scenario thinking is a formal method for questioning assumptions, exploring alternatives, and analyzing the upsides and downsides of multiple possibilities. It is a disciplined way of looking at current and future factors shaping your world, your industry, and your markets, and then analyzing how your organization can plan for and react to future possibilities. Scenario thinking forces you to loosen control enough to rise above conventional wisdom and your own biases.

Deutsche Post DHL executives wanted to explore what the world could be like in five or ten years. They wanted to know what would affect their current organization and their investments in businesses for the future. Hiring an outside consultant to help them assess technological, demographic, and social change, they came up with five scenarios:

- An out-of-control global economy with countries exploiting natural resources and competing with each other for these resources.

- Megacities growing at astonishing rates.

- Lifestyles becoming more customizable.

- Paralyzing protectionism creating barriers to competition around the world.

- Climate change creating global resilience and local adaption.

These scenarios helped Deutsche Post DHL shape a larger discussion about the strategy of the company and which strategic options to pursue—options for both individual businesses and the collective whole. The discussion included people's judgment as to the likelihood that various scenarios would materialize and how well equipped the company was to handle them if they did.

In many paradoxical situations, data don't reveal what's right—in spite of impassioned arguments by finance staffers, operations professionals, and others marshaling dozens of slides and spreadsheets. Numbers alone simply can't point to the right outcomes, because they don't show the entire picture, and they are often based on a set of assumptions that may or may not be correct. Debates over data thus lead to arguments that go nowhere. Who's to say what all the dots of data mean? What's in the black and gray space in between? Nobody can say.

Scenario thinking can help teams pull back from such disagreements, or at least have a more informed and constructive dialogue about differing points of view. It calms the discussion and creates a mechanism for alignment as everyone works together to connect the dots. As people explore situations and develop assumptions together, shared insights emerge. As they test the ideas within a group dynamic, individuals with different views can line up because they are operating outside their usual space—free of baggage and many biases. They don't have to insist on consistency.

Chapter Seven discusses the first way complete leaders can use their heads to resolve paradoxes. This chapter takes up a second. If you want to expand your team's creativity, anticipate possibilities, and assign probabilities, bring people together with scenario thinking. This would be no different from a family reimagining its future by constructing scenarios of moving to three different towns. In one, a university provides a solid economic foundation and cultural environment. In another, an attractive climate and abundant water provides lush agricultural opportunities for self-sustenance. In the third, a burgeoning tech sector provides an economic base for product development, exports, and innovation. The scenarios get everyone thinking more deeply.

The Value of Scenario Thinking

Because of scenario thinking's mind-expanding effect, we encourage leaders to use it regularly. By playing out a story—instead of following a strategic trend line to seek a solution to a supposed puzzle—you can go in fruitful new directions. Cross-cultural research on decisionmaking styles reveals that 75 percent of people in Western societies are fact-based while only 25 percent are intuitive. If you're an engineer or other linear thinker by training, you require a 90 percent probability of success before making a decision—and if the probability dips below that percentage, you delay your decision to gather more data. However, scenario thinking can free fact-based people from their normal mental constraints.

This effect was confirmed by a novel study of 129 executives and workers from ten organizations in which researchers tracked people's commitment to various mental models of their organizations. Employees with political models of their organization—autocratic, bureaucratic, technocratic, or democratic—reduced their reliance on that model after a session of scenario planning. People with financial mental models—believing company control resided in the accounting department—reduced their reliance on their model as well. “From a practical perspective,” wrote the investigators, “this research provides support for the use of scenario planning in organizations as an effective tool for helping employees think differently.”2

Other researchers have shown that scenario planning helps firms capture a range of value, including a better ability to perceive, interpret, and respond to change and improve organizational learning. A 2013 study examined seventy-seven big European firms across various industries that engaged in scenario planning activities. The researchers defined the companies as top-, medium-, and low-performing (according to sales growth) to gauge any differences in value contribution. The data showed that all companies benefited from scenario planning activities, especially in their increased perception: “gaining insights into changes in the environment” and “reducing uncertainty.” But the high-performing firms, the ones that reported the best results, also cited benefits ranging from identifying “opportunities and threats for our product and technology portfolio” to “fostering conversation about the overall strategy of the company.”3

Our experience is that scenario thinking stretches people's perspective. The stories embedded in scenarios extend plot lines in a way that facts cannot. Many younger, more creative companies such as SmarterComics, SynLabs, and BeachMint, which extol creative thinking as their source of growth, engage naturally in scenario thinking. Older, more established companies, where people are asked to push the boundaries of logical, rational, defensible positions backed by multiple PowerPoint slides, normally don't do as well and can benefit the most by exploring it.

The Practices of Scenario Thinking

Over the years, we have developed four scenario-thinking steps to help you push the boundaries of what many people think is possible or logical:

- Take someone else's perspective.

- Define future possibilities.

- Filter scenarios with facts and intuition.

- Diverge and converge.

These steps constitute a coaching method that can guide you in thinking imaginatively about paradox, triggering new thoughts and encouraging people to devise a range of provocative future possibilities, as well as estimating the risk associated with them. As Chapter Seven, the steps require tapping a diverse set of people to engage in the process. Who has the best feel for the future environment? These people should be on the team.

Practice 1: Take Someone Else's Perspective

The first step in scenario thinking is to make a conscious effort to adopt another person's point of view. This simple practice of empathy often opens participants up to understanding, if not accepting, what is important to others. To be emotionally intelligent, you need to get inside another person's head in a way that you can feel what they feel and understand what they are experiencing. This is necessary advance work for scenario thinking.

Most people in top positions are locked into one perspective and consider that perspective vital to being a strong leader. Such certainty in the face of ambiguity, however, blocks their grasp of the motivations and viewpoints of others. The practice of perspective taking sounds simple, but in our experience, a shift of viewpoint is one of the hardest challenges for people in a fast-moving, global, connected world. Ironically, with so much choice, when you select the data, media sources, and even friends to reinforce your own reality and view of others, you become less in touch with what's going on around you. The Internet, though rich in many ways, can actually make us poor in seeing the other side of things.

We often encounter executives who complain about the changing workforce, and we find older leaders in particular cite the lack of commitment and motivation of younger people. These complaints often come from top executives, the best paid, invariably from another generation. They don't believe younger generations want to work hard or make a difference. We have found just the reverse is true, so in such cases, we put together a focus group of young people and convene a meeting behind a barrier that allows top executives to hear but not see the younger workers.

In a facilitated discussion, the younger workers quickly open up about their work lives, in spite of knowing top executives are listening. The flow of the conversation? We ask workers what it's like to work at the company, and they often say it's frustrating, that it's hard to get things done, that they are unclear about the strategy or direction of the company. The executives are surprised; in their experience, at their level, it's easy to get things done and the strategy is clear. We ask workers what it's like to work with their supervisors, and they say it's difficult, that it's hard to get their supervisors' attention because they are so busy, that they don't get a lot of feedback on how they're doing. The top executives easily get other people's attention and mostly know where they stand.

The conversation continues in like vein, the workers becoming more candid as time goes on, and the executives becoming more surprised with each comment. The top brass begins to see that the workers take company values seriously—even more seriously than the executives in some cases. They work hard at advancing their careers, in spite of volunteering in their communities and taking care of families. They are committed and motivated—but they hit roadblocks the top executives never experience.

We then bring the workers to the other side of the barrier to meet the executives, and the conversation takes a congenial turn. The executives ask the questions. They want to learn about the workers' jobs, community work, recreation on weekends, difficulties in balancing work and family, and so on. The executives develop genuine empathy as they realize they are talking to idealistic, committed, hardworking people. They drop jaded stereotypes and invariably leave the session making essentially the same comment: “I had no idea!” They didn't realize they had people of that caliber, who faced so many challenges. In the session, they were touched by a different world.

Short of such a facilitated event, you can develop your perspective taking with the following exercise: Think of a business situation in which you're trying to influence someone you work with—a direct report, a boss, a customer, an outside partner that you know is resisting your leadership agenda. Ask yourself: How am I trying to move this individual? What are my most important purposes, concerns, and values? What are the other person's purposes, concerns, and values? The key is to articulate the other person's wants credibly and convincingly while at the same time clarifying your own objectives.

Now begin to look for the intersection of your own purposes and concerns with those of the other person. What is that person attempting to accomplish or achieve through the behavior in question? Can you see it objectively and compassionately? Refrain from judging that behavior—but try to describe it. What does the person really require? How might this requirement be different from what you had previously assumed? What specific thing might you do or say to fill this need? These questions will help you flex your empathy muscle, which puts you in the right frame of mind to proceed with scenario thinking.

Practice 2: Define Future Possibilities

The next step in scenario thinking is to define some future possibilities that stem from the contradictory forces of paradox. For instance, the paradox that vexes most managers is control versus delegation. On one hand, you may recognize the need to give your direct reports more responsibility and autonomy so you can do more and they can better respond to the issues they face—issues that increasingly require more creative approaches. On the other hand, you feel confident that your insight will speed the decision-making tempo, and you are tempted to intervene, offer guidance, and check up on progress.

Now craft three future scenarios that might affect this situation. For example:

- Two years from now, your boss is promoted, you are in your boss's job, and you now require a flatter structure, a competent individual in your role, and you need to stretch your own capacity because you have been asked to do more and perform at a higher level.

- Three years from now, you're remarried, your blended family has three adolescents, you need to spend more time at home and less at the office or traveling. At the same time, you have a different boss with whom you are not aligned and who expects you to work longer hours and travel more.

- Four years from now, you're managing almost all of your team virtually—some work from home, some are located in other parts of the world, and your company has moved to a hoteling space model and eliminated your office completely. Not only do you lack the ability to monitor anyone's work, the culture of the company now requires trust over supervision.

Think about how your control-versus-delegation decisions could be changed by each of these scenarios. What are the negatives and positives? How will you experience them as the future unfolds? If you in turn apply different mindsets to your scenarios, what actions might you take? Does a purpose perspective give you new insight? A reconciliation perspective? An innovation perspective?

Now consider instead a situation at the corporate level. For instance, at PwC, the global accounting and advisory firm, a team sought to understand the future of talent. What would the future workforce be like? How would it operate? What picture of that future should an executive team consider?

When PwC tackled this issue, it focused on eight opposing forces that it felt would most influence the way people will work in 2020: business fragmentation versus integration, collectivism versus individualism, technology controlling people versus technology giving way to the human touch, and globalization versus protectionism. The PwC team winnowed the forces to the four most important: fragmentation versus integration and collectivism versus individualism. Those forces then governed the creation of four scenarios, which in the process of refinement were reduced to three.4 (See Figure 8.1.) These gave PwC a way to understand how talent shortages, technology advances, sustainability efforts, and demographic and cultural shifts will affect the nature of work in the future.

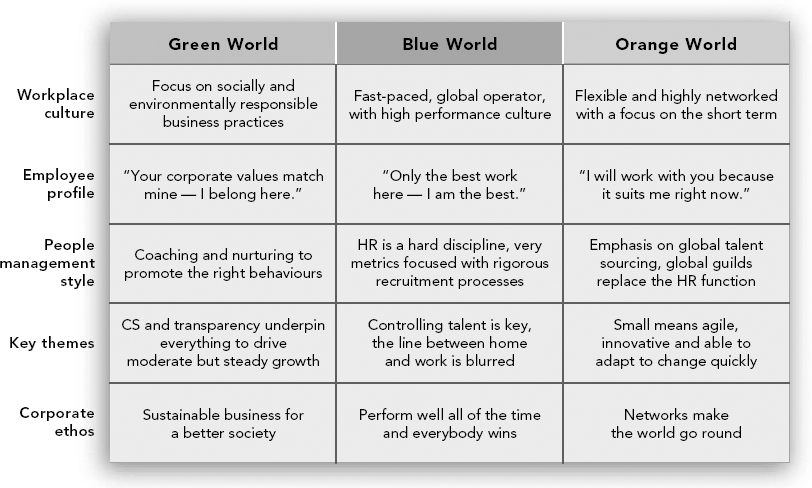

In describing these three scenarios, PwC issued a report, “Managing Tomorrow's People: The Future of Work to 2020.” The report describes different cultural, talent, managerial, and individual implications for tomorrow's workforce. (See Figure 8.2.) This of course will help PwC prepare for managing people tomorrow, and it can also help other companies.

The future states PwC described are relevant not because they predict the future but because they suggest implications executives must consider to prepare for tomorrow. The future will probably not be green, blue, or orange. It will be a world with a combination of factors represented in the three scenarios. As a leader, your task is not to select which world your company will operate in but rather to understand the options and in turn the skills you want to develop in your people today. At the same time, you want to be looking for signals that suggest the actual emergence of certain scenario components. For leaders used to producing strategic plans with single visions of the future, scenario thinking frees up creative thought, allowing you to lay out alternatives and get the company ready to respond.

Practice 3: Filter Scenarios with Facts and Intuition

The third step in scenario thinking is to assimilate each scenario with the help of added data, statistics, metrics, reports, studies, and research. That is, look ahead to dealing with the implications of these future worlds. What will you do? What will your company do? Who can help you? For example, in the hoteling scenario, what specific capabilities would you require to lead in this increasingly likely world? What companies are doing this successfully now? What techniques do role models use who lead others virtually?

Figure 8.1. Three Worlds of 2020

Source: “Managing Tomorrow's People: The Future of Work to 2020” (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2007).

Figure 8.2. Implications for Three Worlds

Source: “Managing Tomorrow's People: The Future of Work to 2020” (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2007).

PwC offers a good example of adding facts to deepen scenario thinking. On top of drafting scenarios, the company interviewed more than 2,700 graduates who had been offered jobs with PwC. Some results confirmed conventional thinking about the future; some defied received wisdom. For example, most soon-to-be-hired Millennials (73 percent) surprisingly expected to work regular (rather than flexible) hours, no matter their country of origin. The vast majority (over 80 percent) deliberately sought work where the firm's approach to corporate responsibility reflected their values—a figure that was nearly the same in the United States and China, at roughly 90 percent.5

As important as the facts are, add intuition to the mix. What do your instincts tell you about the various scenarios? Do you think you would be more controlling or less when working in a more technology-rich environment? How do the facts you've collected inform your hunch about the future and how it will change or evolve? Your intuition, albeit influenced by biases, stems from a rich library of implicit knowledge—unarticulated wisdom that allows you to weigh in on the validity and risk of different scenarios. You can only infer the future from current facts, but by using intuition you have a valuable source of added insight.

In a Harvard Business Review article, Pierre Wack elaborated on merging facts and intuition for better scenario thinking. Wack, a pioneer in the field, believes that intuition is not just a tool to help leaders face difficult choices, it actually helps leaders creatively expand their view of the world. Writes Wack: “Scenarios deal with two worlds: the world of facts and the world of perceptions. They explore for facts but they aim at perceptions inside the heads of decision makers. Their purpose is to gather and transform information of strategic significance into fresh perceptions. This transformation process is not trivial—more often than not it does not happen. When it works, it is a creative experience that generates a heartfelt ‘Aha!’ from your managers and leads to strategic insights beyond the mind's previous reach.”6

One technique we use to get leaders to employ their intuition is to ask team members to suggest how they see a particular paradox-related story about the future unfolding. Then we put key words from each person's story on a chart and use that device to discuss what is likely and unlikely to take place in this future scenario. Is the current obsession with growth likely to be relevant five years from now? How important will sustainability be in this scenario? We can also ask practical questions about what leaders can do now. For example: What type of cost approach do we need to begin building today?

Practice 4: Diverge and Converge

The final step in scenario thinking is to diverge your thinking and then converge it. To do so, share strategic or personal scenarios with a diverse range of people, both within and outside your circle: direct reports, peers, consultants, partners, and students. The more people involved in building scenarios, the more accurate the scenarios are likely to be. With a diverse group, you can churn out possibilities and take conversations in wide-ranging, unexpected directions—just as at Deutsche Post DHL and PwC.

We are suggesting a form of crowdsourcing, involving a wide range of people and perspectives, to increase the amount of creativity and knowledge integrated into each scenario. In bringing together diverse viewpoints to inform scenario thinking, you challenge the assumptions embedded in each scenario. Of all the things we've considered and discussed, what assumptions do we think are most valid about the future? What degree of likelihood (and risk) would we associate with each scenario? What plan of action seems feasible given each scenario? How well would we respond to each scenario if it were to occur?

When Deutsche Post DHL wanted to test various scenarios and strategies, it brought together groups of younger high-potential leaders around the world and asked them to critique, challenge, or reinforce different assumptions and scenarios. The company assumed that technology would play a larger role in logistics and that younger employees, being more wired and technology savvy, could provide the best input. The executives were right—the young leaders challenged, revised, and ultimately produced a much better product that took into account the future role of tools the younger managers knew intimately—social media, mobile computing, location tracking, massive analytics, and so on.

The younger workers understood better than their older counterparts the impact of social media, online shopping, and the impact of one's network on buying decisions. In the unfolding Deutsche Post DHL strategy, many strategic choices about how to serve customers in the future were shaped by the input of these younger colleagues, who played an important role in the strategic planning process by offering a different perspective on the impact of technology.

Following diverging and converging, leaders will find the scenarios that best suggest ways of managing paradoxes. For most companies, managing the paradox of preserving the core traditional business versus investing in adjacencies to develop future businesses bedevils management teams and leaders. Scenario thinking is particularly helpful in dealing with this paradox, as the tendency is often to go with the known core when money becomes tight. Should Deutsche Post DHL consider new businesses suggested by scenarios or stick to its knitting? As noted in Chapter Three, as an effective CEO Frank Appel voted to invest in the future of his businesses. But the right action depends on the circumstances, and Appel will naturally reconsider the actions as circumstances change.

Follow Up by Acting

If you're a senior leader, consider the question posed by Marcel Cobuz, senior vice president for innovation at Lafarge: “Do you have a breed of managers who see paradoxes everywhere, or are people simplifying the world?” If you think strictly in terms of implementing a single strategic plan, you may be simplifying the world into a puzzle. With so many contradictory forces acting, no single plan can get the future right. Understanding the implications of paradox calls on complete leaders to rein in their urge for control, consistency, and closure. Instead, they want to play out the different possibilities for resolving the tensions of multiple contradictions. Scenario thinking is the tool for doing so.

Once you have gone through these four steps, you should have advanced your skill in comparing and contrasting alternatives, a tremendously valuable capability in jumping over the line to deal with problems in a complex, volatile world. But beware a common mistake: Failing to do anything in response to your scenario thinking. This is the point where scenario thinking most often breaks down as a tool to deal with an organization's contradictory forces. You may go through the exercise pro forma rather than as an engaged participant. You fail to ask yourself: What core insights have emerged from this process? You don't ask the critical question: What can I actually do with this wisdom? You generate ideas, but you don't turn these ideas into usable plans and actions.

We return to this challenge in Chapter Twelve. In the meantime, note that the costs associated with not acting grow exponentially as you become a more senior leader. The intensity of choice and intensity of consequences both mount. That very intensity should be an incentive for redoubling your efforts to find common ground in scenario thinking, and in turn, uniting with your collaborators in common action.