6

Applying the Panarchy Principle

Acquiring knowledge at school is one thing, but we also have to learn what the real world is like. MoM TiSH introduces us to the dynamics of society.

So far, we have discussed the need for transformation, a platform, a transformation task force, and new skills in systems engineering and community building disciplines in this task force. We filled our toolbox to model this transformation. However, to be effective, this requires getting everyone on the same page regarding the shared mental models so that they can move from one tread to the next.

In this chapter, we will look at community building. The engineering and medicine disciplines in the task force need to understand the dynamics of community building and how to take it into account when designing new technology-enabled care platforms.

Where we pointed to INCOSE for great resources on systems engineering, we will also refer to the systems innovation network for community building. First, we will introduce the ecocycle and panarchy models and introduce supporting ecocycle submethods to define the dynamics of community building. This will provide a brief overview of awareness on the dynamics of change on all levels, though one chapter is not enough for a deep dive.

Then, we will learn how to use the principle of interdependent ecocycles to determine people’s states of mind and help plan the transformation. Overcoming inhibition is important in ecocycles as it might slow down the transformation.

In this chapter, we’re going to cover the following main topics:

- Transitioning from tread to tread

- Understanding ecocycles and panarchy

- Applying the panarchy principles to TiSH

- Understanding people’s state of mind

Transitioning from tread to tread

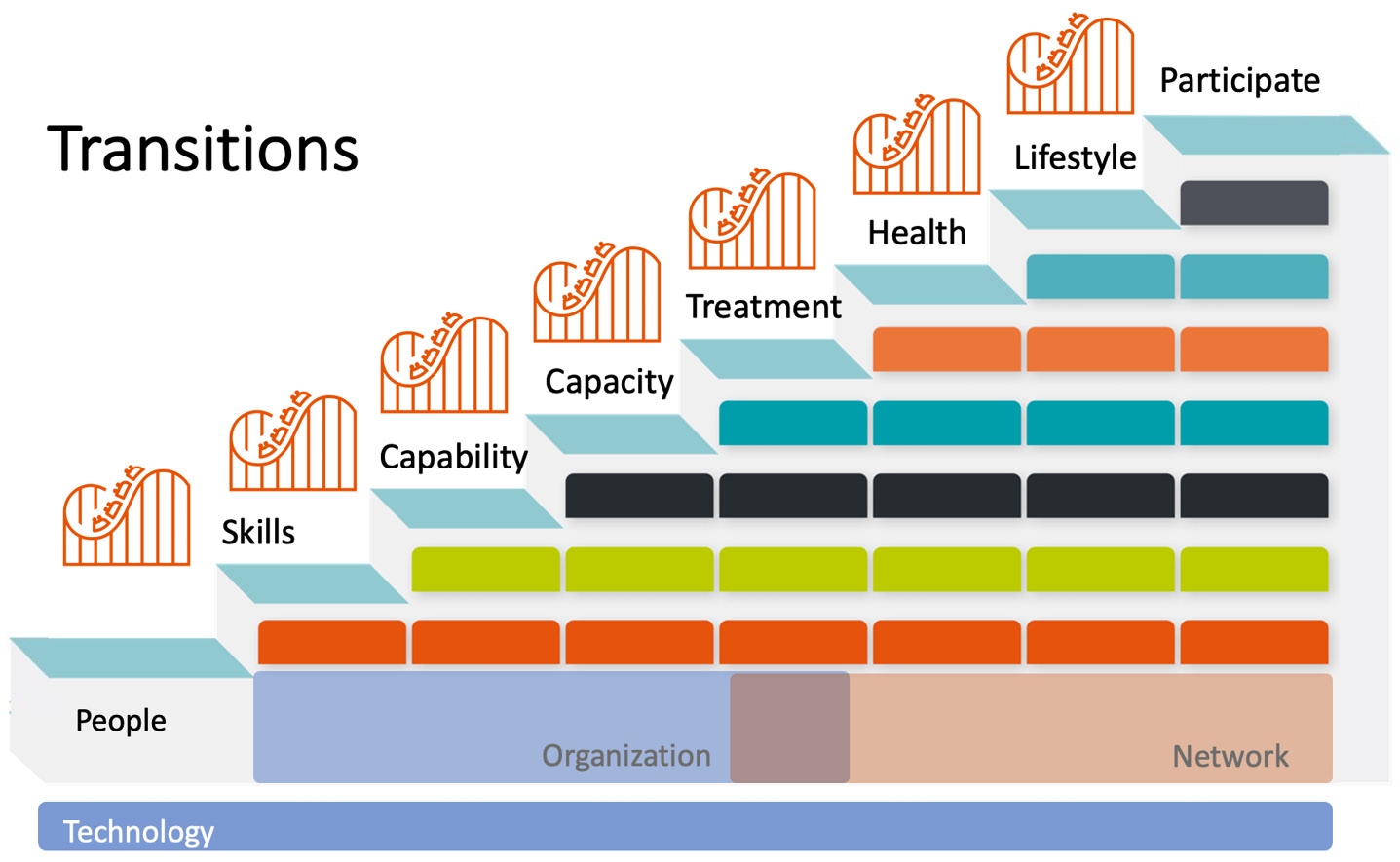

This is a good moment to have another look at the TiSH staircase that we presented in the previous chapter. In that model, we presented treads and stages of transformation. What we haven’t discussed in that model was how to get from one tread to another. This is where transformation hits: with every step that we take to the next tread, we will find that these treads are rollercoaster rides. We need to carefully plan and time our ride and be aware of the fact that it will move at different speeds as circumstances such as bends, loops, and hills will change. The TiSH staircase might appear as something in which we can plan everything, but the reality is that we can’t always plan where our feet are concerning our heads on every step.

We take this rollercoaster metaphor to symbolize the dynamics of change. These dynamics have different grounds but people’s state of mind is something that can be determined; then, these insights can be used to define the transitions taken in the transformation:

Figure 6.1 – Transition rollercoaster for each tread

Each higher tread means growing in scale with each transition. This starts with individuals and then ever bigger groups of people with new goals to achieve.

The first tread is the transition to having enough people with the right digital skills. The second is the transition to capable TEC teams, the third is the transition to enough capacity, and so on. If the transformation can be done tread by tread, then this is manageable, but what we see in the real world is that the transitions on all treads take place simultaneously at different speeds. These transitions also influence each other. If people are not skilled enough, then this will inhibit the transition on higher treads. Another example is that if the rules on health values are not clear, this will cause certain treatments not to be reimbursed. The transitions influence each other from both sides.

We need to understand the rollercoasters on each transition and how they influence each other for a successful transformation. This is where ecocycles and panarchy come in.

Understanding ecocycles and panarchy

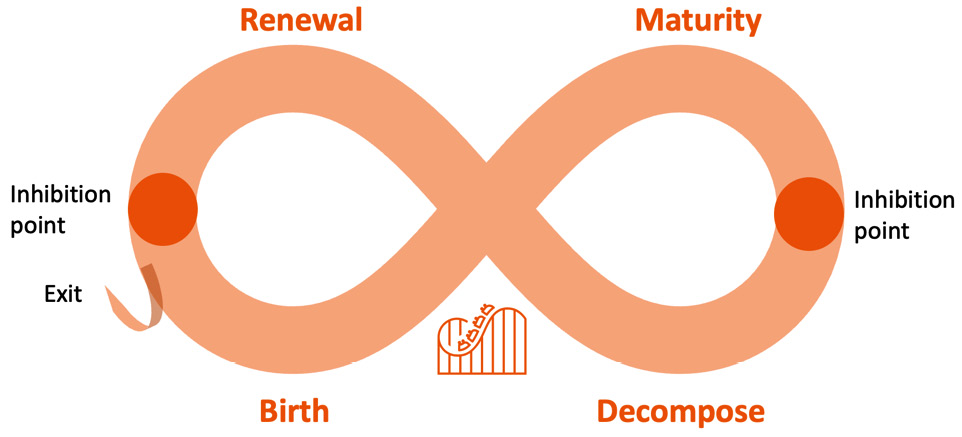

The metaphor of the rollercoaster needs some more definition to be practical; we need to know more than that it could be a bumpy ride ahead. Therefore, we must introduce the generic ecocycle model to determine people’s and the organization’s state of mind:

Figure 6.2 – The adaptive ecocycle

This ecocycle can be viewed as a rollercoaster, which consists of the following four states of mind:

- Maturity: Things are continuing as usual; there’s no need for change

- Decompose: The old has to go; something new is needed

- Renewal: New ideas are explored

- Birth: New ideas are put into practice and grow toward the new normal

There are also two inhibition points. The inhibition point on the right denotes not letting go of the old. People feel that something has to change but do not make the step to do so. The inhibition point on the left denotes not deciding to invest in the new way. People know what to do but experience a lack of funding.

Different people tend to be in different states of mind, and not all states are fruitful enough to invest time into building new common understanding. The urgency for change must be commonly felt. It’s in the Renewal state that common understanding has the best opportunity to change.

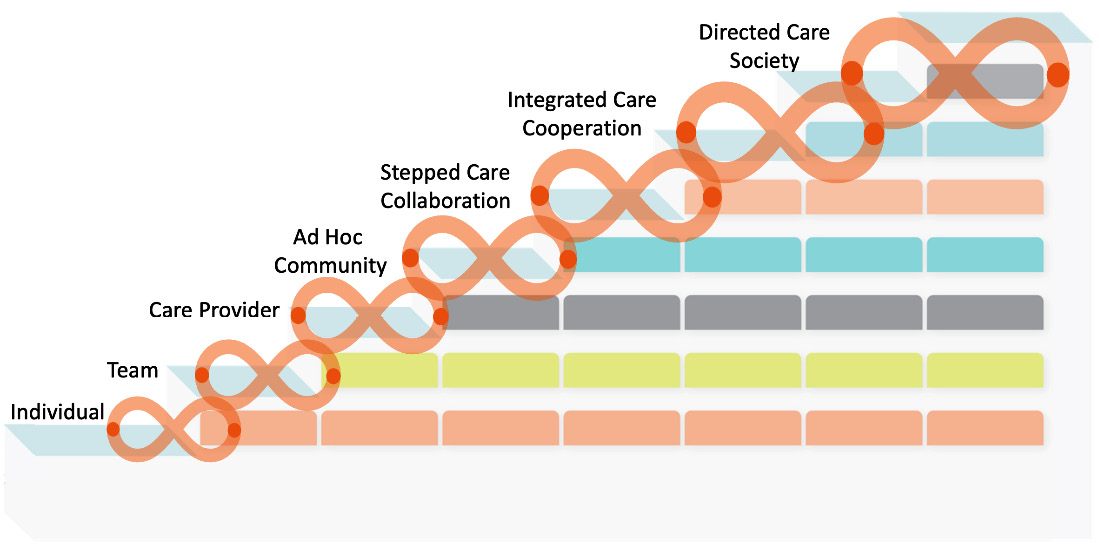

This ecocycle can be applied to all scales of people and all transitions, from the individual using the technology to groups of people in teams, organizations, and networked care forms:

Figure 6.3 – The adaptive ecocycle on all TiSH scales

Determining where on each scale the prevailing state of mind is and where the inhibitions points are will help in planning the transformation.

This way of viewing complex systems is called a panarchy, a complex study that seeks to explain how economic growth and human development interact and depend on ecosystems and institutions. In our experience, we have applied this to healthcare too: assessing the (global) growth in healthcare and how ecosystems in healthcare interact with each other. Something key in panarchy is the adaptive ecocycle: how do individuals and groups adapt to changing circumstances across the scale from individuals and departments in healthcare institutions to networks in the societal ecosystem?

In our situation, the vast potential of technology plays a significant role in this. Some of these technological circumstances can be influenced; others can’t. What is the overall impact on healthcare and how can we deal with this in the transformation? Panarchy is, as mentioned previously, complex, but in this chapter, we will try to explain how it’s relevant to the transformation of healthcare and how it gives insight into the design and helps execute the transformation.

We need insights into creating an understanding of how to model the behavior of individuals, teams, organizations, and networks in different circumstances and situations. Simply put, how can we get people in organizations, teams, and team members, as well as their clients and suppliers, on the same page and get them to share a common understanding on how they achieve goals?

People will find themselves confronted with circumstances that develop faster than they can comprehend. They will discover that networked care will increasingly become more important and how technology is accelerating that. The development of technology might be faster than teams can absorb. This is exactly what the concept of panarchy and ecocycles can model and describe.

Tip

To learn more about panarchy as a concept, we recommend reading a paper by Paul. B. Hartzog entitled Governance in the Network Age. His definition of panarchy is complexity + networks + connectivity = panarchy. He describes panarchy as an emerging complexity of social and political structures that continuously form new networks that interact with each other and are supported or even propelled by technology. The forming and the levels of interaction take place at various speeds, causing some networks to be more advanced and others to lag. This is what we see today in healthcare at different scales: individual, local, regional, national, and even global.

Other sources where you can learn more include Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems, by Gunderson and Holling, and the Ecocycle Planning section of the Liberating Structures website, https://www.liberatingstructures.com/31-ecocycle-planning/.

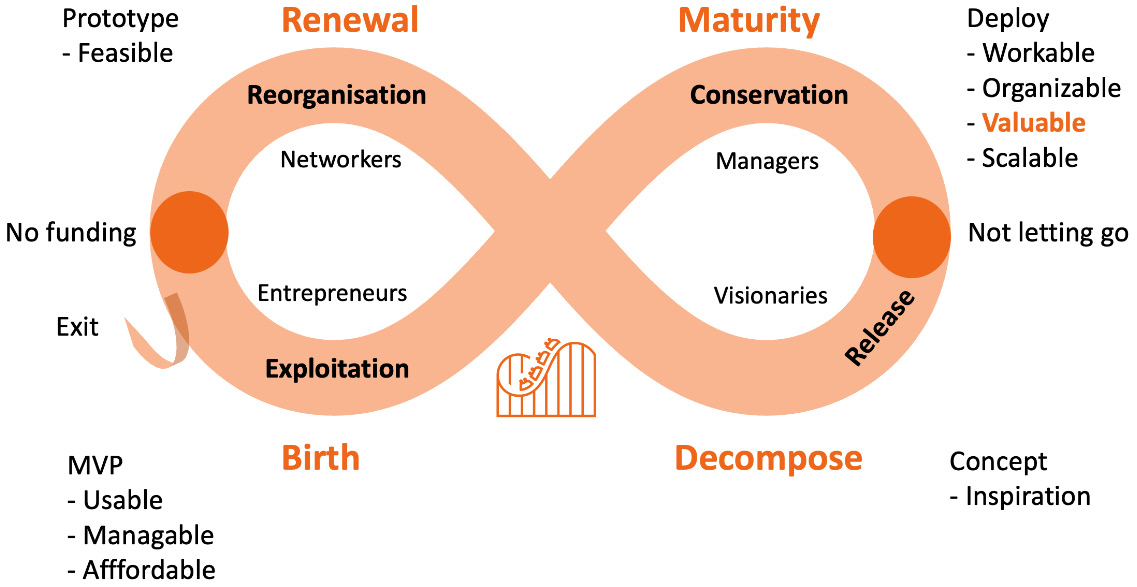

To be able to understand the dynamics of the panarchy, we are building on the basic ecocycle. First, we must add some extra characteristics for each stage of the ecocycle and the roles involved:

Figure 6.4 – The adaptive ecocycle – stages, roles, and criteria

The four stages in the adaptive ecocycle are as follows:

- Exploitation: This is the phase of birth and fast growth. Here, we can think of the introduction of new technology and/or a way of working in a society that is rapidly adopted by a population.

- Conservation: In this stage, we see stabilization; for example, the new technology is adopted by a larger population and, as such, maturing because they see the benefits and value.

- Release: The growth declines because, for example, the populations need changes that require different technologies or, due to changed circumstances such as a different attitude to privacy, populations abandon the new technology or service as a whole, seeking something new to fulfill the changed requirements.

- Reorganization: This is about renewal. Because of changed conditions such as demographics, the technology needs to be renewed to address the new circumstances. From this point onward, the cycle starts over again or exits.

Each stage has different people involved with different roles. Exploitation is led by entrepreneurs who start – or give birth – to new endeavors; the managers mature the endeavor and conserve its advancements. In this stage, it takes a creative visionary to become the game-changer who releases themselves from conserved thinking by decomposing the new needs into new possibilities. The networkers integrate new possibilities to renew the available solutions and enablers. These renewed possibilities inspire entrepreneurs.

Each of these roles has a different perspective and criteria they look at. The visionary is looking for inspiration and ideas, whereas the networker seeks the feasibility of the idea, preferably with a prototype or proof of concept. The entrepreneur looks at usability, manageability, and affordability, starting with a Minimal Viable Product (MVP), whereas the managers are looking to see whether the platform is workable, organizable, valuable, and scalable. The term valuable relates to our value stages.

Another characteristic is that the stages do not take up equal time, nor do they behave as clockwork. Think of Exploitation and Conservation as the lift hill of a rollercoaster (Figure 6.4). A ratchet clicks with every advancement to assure the gained improvements. The Release and Reorganization stages are more like the rest of the track, providing enough kinetic energy to complete the entire course under a variety of disrupting conditions and start the cycle again. This metaphor gives insight into two crucial points on the track: the release point on top of the hill, with the option of not letting go if it’s not safe, and boarding the new ride. Who wants to buy or invest in new tickets? Both can inhibit the carts to move further.

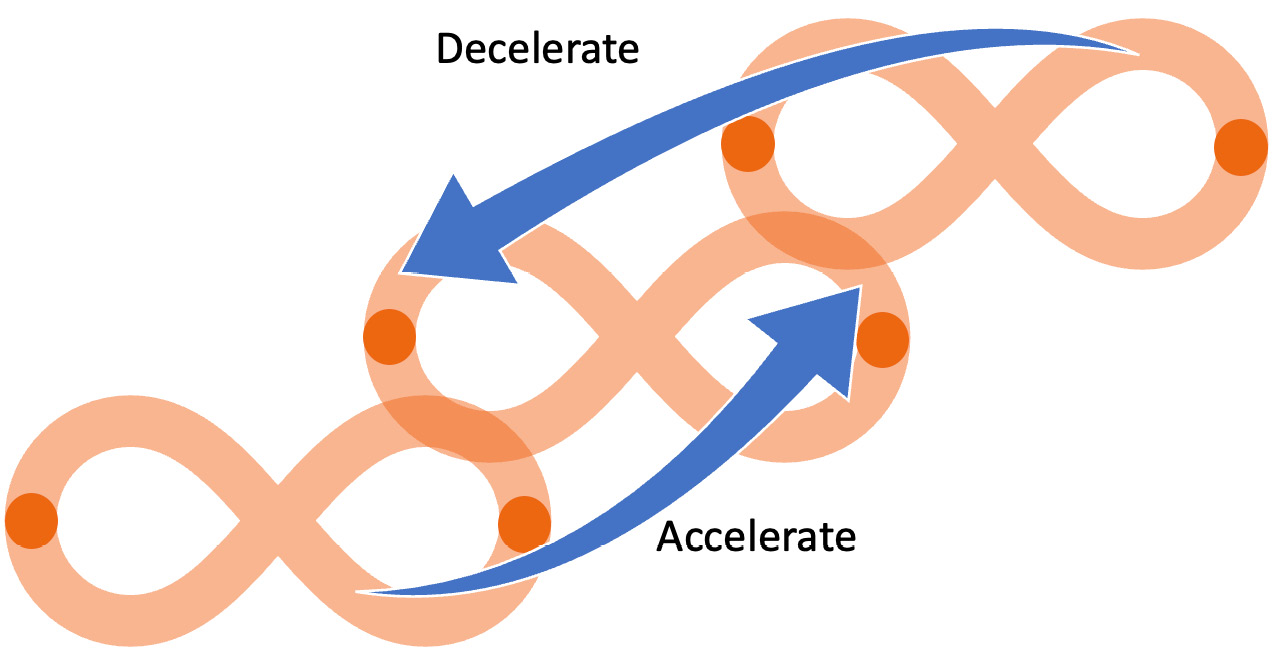

These inhibition points are influenced by the ecocycles of the other treads. As shown in Figure 6.5, these connections make up the panarchy:

- From new ideas in the Release stage to the last phase of the Conservation stage one tread up, the revolution from below accelerates the transformation

- From the experience gathered in the Conservation and Renewal stages, the tread acts as a conservative force, which decelerates the transformation from above:

Figure 6.5 – The panarchy connections

For example, if a new technology is picked up by a visionary, this can trigger the team if they are at the end of the Conservation stage and starting to come across dilemmas. Only then will they consider this new technology and let go of the current way of working.

If the team does let go and comes up with a new way of working, it’s the next inhibition point that has to be overcome before the Exploitation stage can begin. The organization’s previous experience, culture, and heritage will influence the team in the Renewal stage and probably tell them that value must be created for the organization. In our case, this is the capacity to provide reimbursable health services. If the organization itself is in another stage of its ecocycle, it becomes less clear what the influence is. A natural way is when the ecocycles synchronize where they overlap in the panarchy. If the individuals already have the right skills for the new technology, it’s easier to start the Exploitation stage in the team to build their capabilities. When that is matured, this can form the basis to start building enough capacity in the organization.

With these loosely coupled but further independent dynamics of each tread ecocycle, the transformation task force will not be able to plan the transformation. What it can do, however, is understand the dynamics and use those dynamics to facilitate transitions when the timing is right.

Understanding is also key to driving each ecocycle. The task force can facilitate common understanding activities with the methods presented in this book or others if they’re more suited for the specific situation.

It’s the task force that must identify these stages and act with common understanding activities when the time is right.

On an amusing note, it can be said that the task force has to wait for the right alignment of planets on their cycles, just like an astrologist does.

Planning the ecocycles

Technology releases can occur daily, but learning new skills takes weeks. Applying these skills to the teams takes months, (re)organization takes many quarters, and networked care can take years to a decade. However, we can accelerate the cycle times by creating a common understanding.

Here is how to achieve this:

- Determine in which ecocycle stage each tread is.

- Plan and execute common understanding sessions with the shared mental models suitable for each tread.

- Involve the treads below and above the panarchy to help the accelerators trigger the release and the decelerators avoid not getting funded, respectively. This must be aligned with the stage of the ecocycle as shown with the blue arrows in Figure 6.5.

- Use common understanding to agree on the transitions required and make plans accordingly.

Now that we are aware that ecocycles and panarchy help us understand people’s state of mind and the growing pains of change, let’s learn how this helps us further understand the complexity of transformation in healthcare. We will do that in the next section.

Applying the panarchy principles to TiSH

We will start this section with a general remark that applies to almost every transformation, but specifically to digital transformation. Typically, technology moves faster than the organizations that need to adopt the technology. Healthcare is no exception to this rule. However, transformation is a journey. It requires a plan and planning to get where you want to be as an individual, team, organization, or network, which helps you define what you need to complete the journey. That’s where the TiSH staircase comes in: it describes the different transitions in that journey.

With every transition to a new tread, we must prioritize, balance, and consider viewpoints while focusing on the bigger picture, which is the ultimate goal that we are trying to achieve. Let’s take the necessary steps.

The challenge is that DevOps development and releasing the new technology will potentially be faster than the adoption of that technology in organizations and society at large. We can see this in the TiSH staircase: every person that is confronted with new technology must go through a transition, as well as all the treads above that. If we do a release from DevOps, we must consider how this is impacting the treads in the staircase. Monitoring the stories on perceived value on all treads becomes the essential source for renewal.

From the bottom up of the TiSH staircase, we have technological revolutionary forces driving innovation; from the top down, we will be confronted by constraining forces that simply need time to understand and adapt to the innovation. The power of TiSH is having a common understanding – with shared mental models – to achieve the goals. The key is that technology accelerates the (eco)cycle time, which can lead to revolution (fast adoption) when needs are understood well.

To understand when those needs surface and can or will be told, we can use the ecocycles in the panarchy from bottom to top. This will help with the DevOps part of the platform with a needs-based release as it will know when and how to listen based on the following:

- Individuals that recognize their state of mind

- Teams in their development state

- The organization stage

- The care networks stage

Let’s explore the panarchy for this purpose.

Defining the individual ecocycle

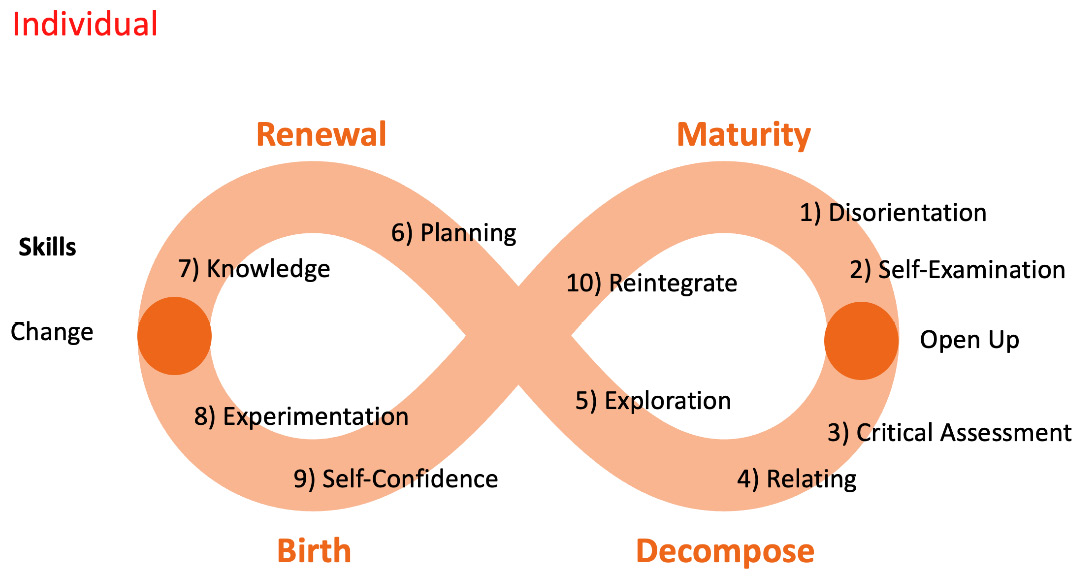

The first thing technology encounters on the TiSH staircase is the individual user and their ecocycle. Let’s have a closer look at how people adopt innovations. We have chosen to use the Mezirov model for that. It describes the transformational learning phases a person goes through in adopting innovations:

- Disorientation: A dilemma that challenges the current normal situation.

- Self-Examination: Reflect on the current situation; is it sustainable?

- Critical Assessment: Question whether previously held beliefs are future-proof.

- Relating: Recognize you are not alone.

- Exploration: Possibilities in the new situation, new roles, and relationships.

- Planning: Plan to implement the changes.

- Knowledge: Strengthen your skills and learn what you need to adapt.

- Experimentation: New roles and ways of working.

- Self-Confidence: Built competence and capabilities (group).

- Reintegrate: The new way of data-driven working as the new normal.

We can plot these phases onto our ecocycle pattern, as shown in the following diagram:

Figure 6.6 – The individual ecocycle

What is the connection between technology and this individual ecocycle? The influence between the ecocycles is complex but can be modeled in such a way that we can apply our reasoning to it.

But how do individuals get caught in a dilemma? This happens because they are team members. It’s the transformation of the teams where the dilemmas originate.

Note that from the exploration learning phase, the individuals can influence the teams they are part of to accelerate the team ecocycle. On the other hand, if the team is performing well, it can inhibit how newly gained skills are applied to the experimentation phase.

Common understanding can be improved by organizing Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act (OODA) sessions to build a shared mental model of how technology can help organize healthcare at the activity level. To determine what topics should be addressed in such sessions, the Activity Triangle can be used as a template.

Defining the team ecocycle

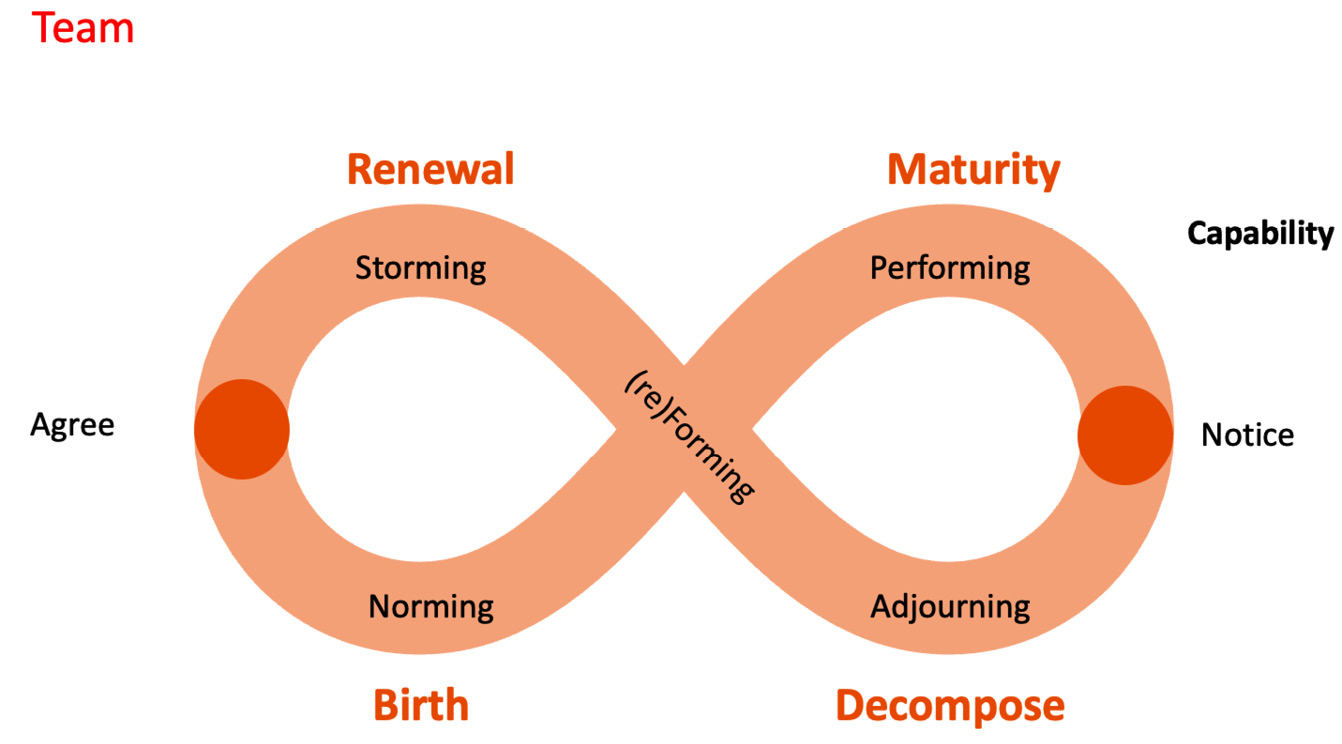

If we move one level up to the teams, we can look at Tuckman’s model of Team Dynamics. We discussed this model in Chapter 5, Leveraging TiSH as Toolkit for Common Understanding. Tuckman describes how teams go through different stages – forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning – to get to know each other and then jointly define how the purpose and goals can be best met as a team. The team ecocycle is shown in the following diagram:

Figure 6.7 – The team ecocycle

The step from adjourning to (re)forming is the point at which the organization’s influence can cause the current way of working to be released. Note that not all teams will go through this cycle at the same time. It will probably start with a more progressive team in the organization.

The organization can influence the inhibition point to let the team agree on new norms if the organization does not see how their value in increased capacity would be realized.

The task force can organize common understanding sessions on customer or health journeys to discover the value of teams working with new forms of technology at the touchpoints on that journey.

Defining the organization ecocycle

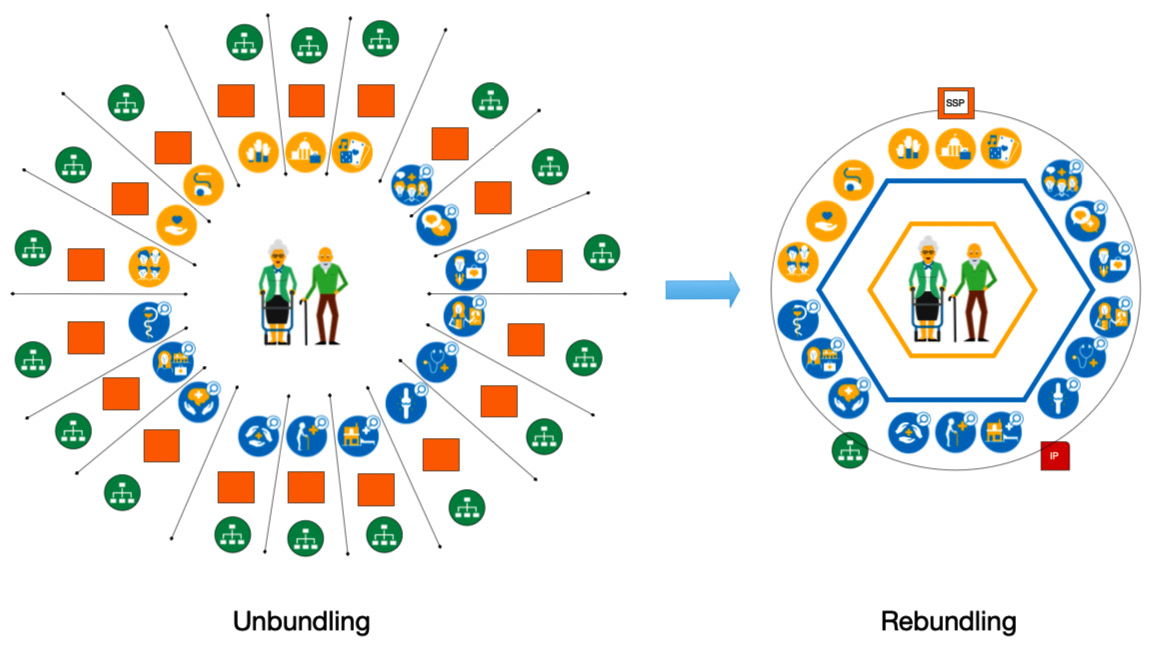

The next level is organizations. For this, we can use Rendanheyi again. We discussed the concept of Rendanheyi in Chapter 4, Including the Human Factor in Transformation, where we described it as an organization wherein the employer doesn’t listen to the one that sits higher in the hierarchy of the organization, but to the user or, in our case, the patient:

Figure 6.8 – Unbundling and rebundling healthcare organizations

This is all about the patient’s health experience or HeX. Care organizations that adopt Rendanheyi would be better equipped to listen directly to the patients and provide care regarding the exact needs of the patient. The organization is unbundled into micro-enterprises and then rebundled into ecosystem micro-communities for customer-focused operations, demolishing existing silos in the organization. The organizational silos are demolished, so to speak, and the care teams are enabled by the shared service platform (SSP) with shared resourcing, which is governed by the industry platform (IP).

How can we put this in the ecocycle pattern? Each development stage can follow the platform design toolkit (PDT) phases and Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Enabling Organization (EEEO) toolkit from Boundaryless.io to achieve this value with the following:

- Exploration

- Strategic design

- Validation and prototyping

- Growth hacking

Without going into detail now, the takeaway from this approach is to concentrate on customer value and not fixed procedures or guidelines. In Chapter 9, Working with Complex (System of) Systems, Chapter 10, Assessments with TiSH, and Chapter 11, Planning, Designing, and Architecting the Transformation, we will dive into micro-enterprises and ecosystem micro-communities in more detail.

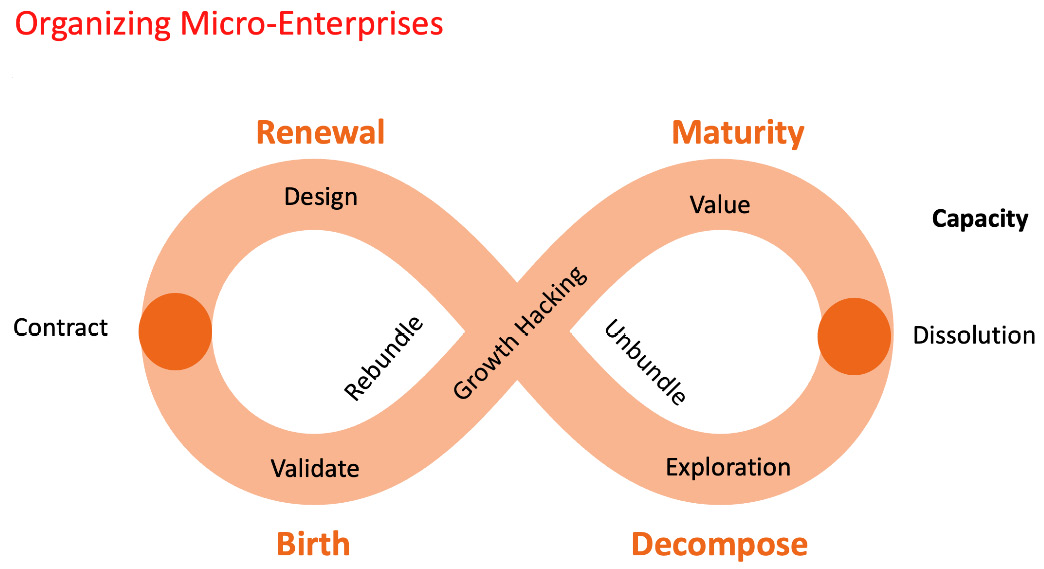

We can plot the platform design phases in the ecocycle to organize micro-enterprises, as shown in the following diagram:

Figure 6.9 – The ecocycle for organizing micro-enterprises

The value at the organizational level is in creating enough capacity in micro-enterprises to provide healthcare required by the patients. It’s the capacity to deliver that creates revenue. The panarchy connections, as put forward in Figure 6.3, are that in the Exploration stage, the organization can inspire the upstairs networked care treads to consider letting go and get involved and accelerate transition because capacity is available. On the other hand, if no added value is recognized, this will lead to the inhibition to contract the organization to build the capacity for delivering the new networked care. This transformation can be accelerated by organizing common understanding in HeX sessions so that more focus is put on the patient and how to optimize the value in the care network with a platform.

The challenge now is how to transition to the next networked treads, as shown in Figure 6.10 in the next section. After all, the team of teams and organizations need to adapt to these forms of networked care. We can do this by following the unbundling and rebundling cycles, as per the networked care type:

- From unbundling traditional hierarchical structures in organizations to rebundling virtually in connected organizations for ad hoc networks around patients. The organizations know of each other’s actions. They are visible to each other.

- Rebundling again via teams collaborating and forming the HeXagon by understanding each other regarding why they are involved in the network and coordinating accordingly in a formalized way.

- Using the acknowledged platform that supports the HeXagon to plan what has to happen in the integrated care plan.

- Building the ecosystems for directed care in the HeXagon to jointly determine the best cause of action.

The panarchy connections explore new ways to utilize the platform and trigger upstairs and being of value as a prerequisite to downstairs getting contracted.

Defining the care network ecocycle

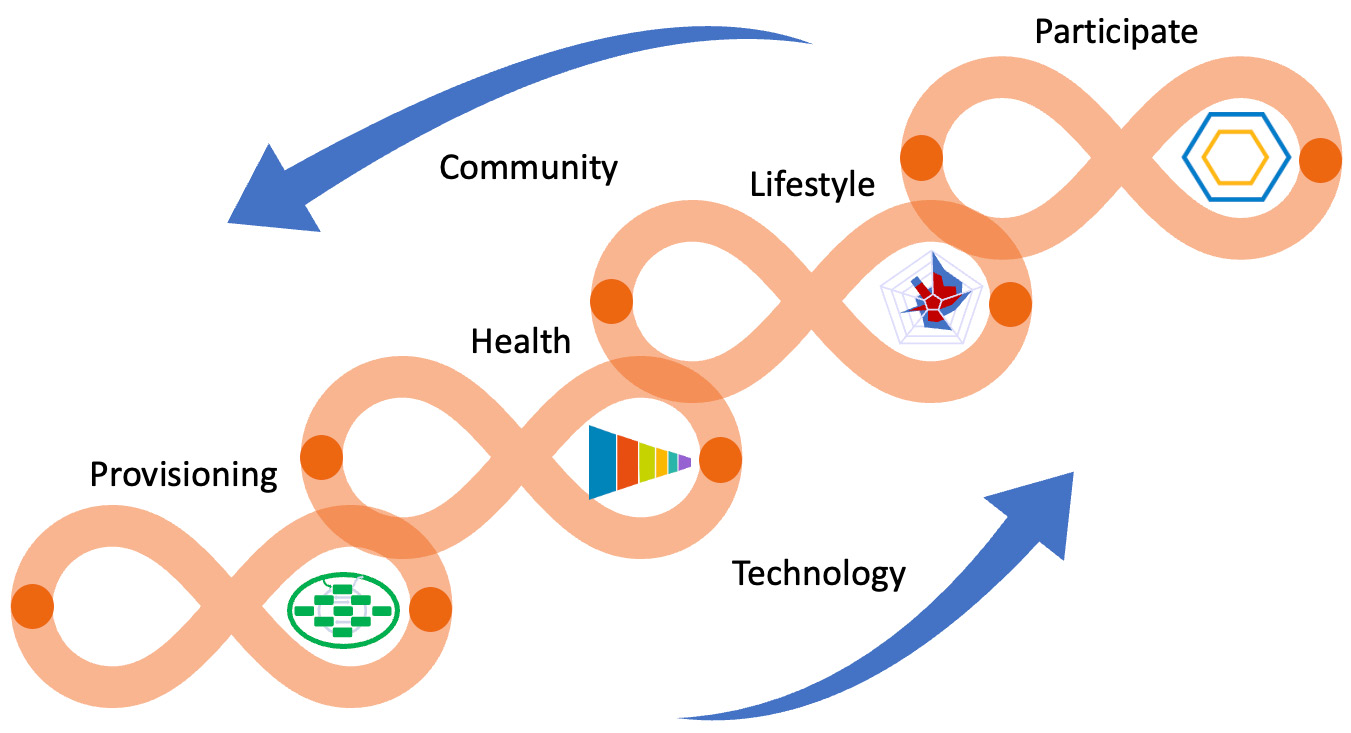

We can define the care network ecocycle by getting a common understanding of respective case management, stepped care, integrated care, and directed care models:

Figure 6.10 – The care network ecocycle

The platform consists of the technology that triggers the acceleration and the community that decelerates to determine the value before applying the platform. Both forces are essential to driving the transformation.

From the perspective of teams, they can experience the evolution toward a true ecosystem while still in the claws of the hierarchy, then the loosely forming virtual network around the patient and the serious steps of the team of teams and the platform, and finally, the ecosystem.

Note

To understand the developmental stages of networks, the works of David Ronfeldt are insightful. His TIMN model stands for Tribal (kinship), Institution (hierarchy), Market (competition), and Network (connection).

It’s the willingness to let go of the hierarchy that prepares the ground for unbundling. The lack of value seems to be the most obvious reason for the dilemma. Therefore, asking what true value we will deliver to patients and people is what leads to reasoning in how value is added to the ultimate outlook on participation. As Stowe Boyd writes:

That’s why we are transitioning to platforms that support ecosystems, and the organizational form best suited to this is the “team of teams” model, such as Rendanheyi. Platform ecosystems will favor the team of teams organizational model for the participating companies.

Now that we have built our panarchy and established the interaction between the ecocycles, it’s time to learn how the task force addresses the inhibition points. Therefore, we have to go back to people again. It’s their state of mind that will determine how the transitions take place. Can we identify certain archetypes of behavior in change and can we look at this at the group level to understand why an individual, team, organization, or care network is at that point in their ecocycle?

Understanding people’s states of mind

In the previous section, we discussed two main movements in transformation: technology-driven acceleration and community deceleration or inhibition. Simply put, technology is developing faster than the community is accepting and capable of adopting new technology. Often, this is explained by the fear of that new technology, but that’s rarely true. The issue is that people are not trained to use the technology properly or they are not convinced of the added value. This is probably the main reason developers have a poor understanding of the real needs. The latter is typically fed by perception. Misperception or myths lead to inhibition, especially since one of the characteristics of societies is solidarity and protecting other people. Myths are widely spread and often rigidly fixed, reinforcing inhibition. Only some disruption will break this force. This force is called understanding customer needs. With this force, DevOps can create real value.

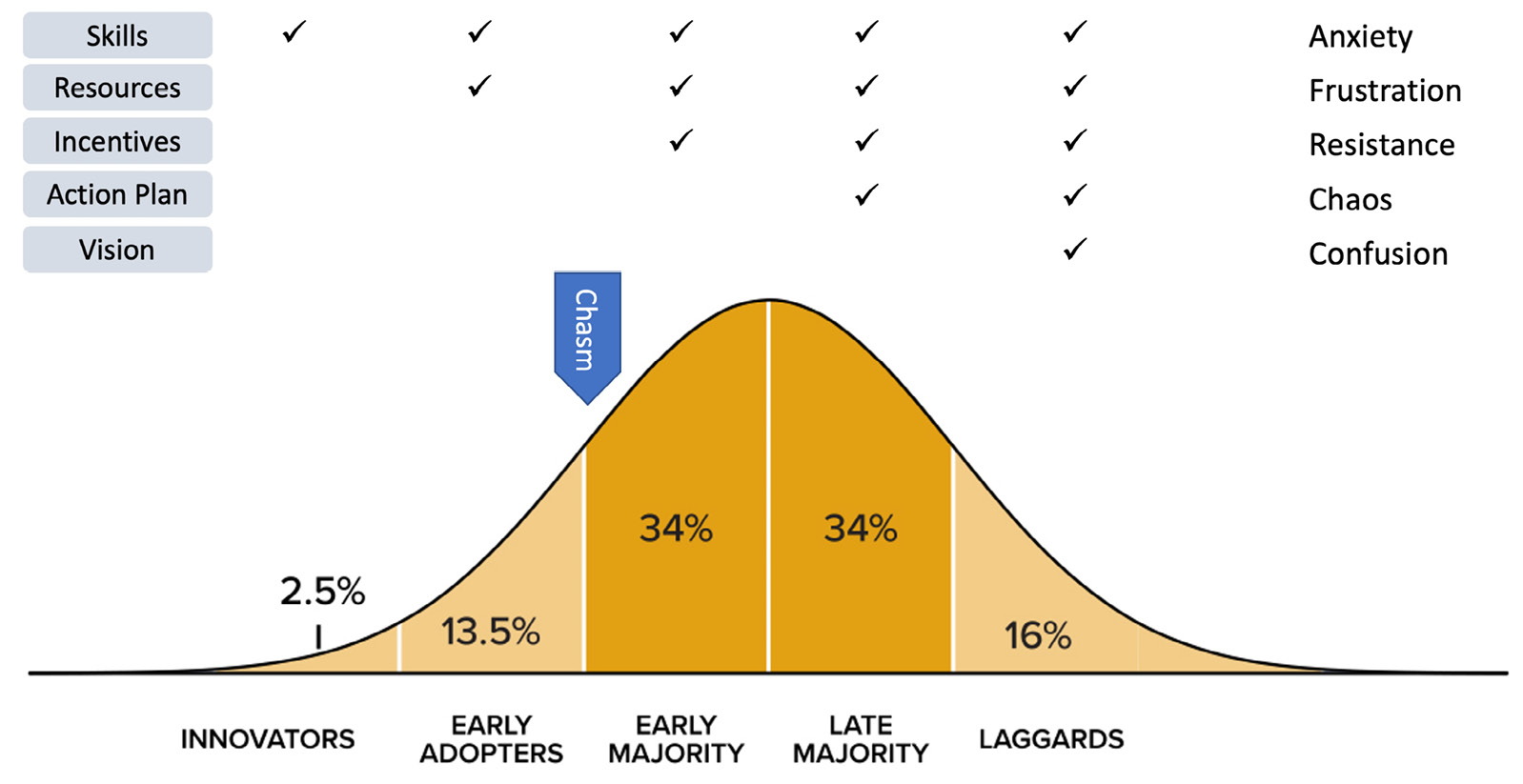

How do we overcome inhibition by understanding the needs of the people involved? Let’s present some widely used transformation models to understand their stories and behaviors: Lippitt-Knoster, Rogers, Moore, and the already explained Mezirow. The Lippitt-Knoster model might be a good tool to start with since it describes the emotions of the people involved. This is very useful in our human-centric approach. Lippitt-Knoster describes the various ingredients to make a complex transformation successful. This model is shown in the following diagram:

Figure 6.11 – The Lippitt-Knoster model for Managing Complex Change

Next to the formal ingredients is the need to create change and transformation, which also addresses the emotions associated with change. This can be very helpful when exploring ideas and designs. As architects, we must take the following steps:

- Start with a Vision and an Action Plan (through mission, goals, and strategy). This prevents false starts and Confusion.

- Make sure that the (digital) Resources are working perfectly together, including the support of these resources. The users must be encouraged to develop their Skills while addressing Anxiety and Frustration.

- Make sure Incentives are in place (create personal actionable urgency) and avoid anticipated Resistance.

It should be clear that behavior is an essential, if not the most important, element in transformation in each tread, especially in the speed at which innovation is or has to be adopted. There has to be a clear incentive or urgency. If a project is not giving the expected functionality and support, the transformation stops here with a lot of frustration and anxiety. This is the fundamental challenge for the architect: they need to find a solution for this. At the very least, they must be able to understand the consultants and medical staff regarding what the requirements must be. However, architects should also have an understanding of how users will respond to the introduction and adoption of innovative solutions. The architect can use this to define the incentive to get to faster adoption. Again, the digicoaches, e-nurses, and lead users play an important role in this.

Another well-known model is the Rogers adoption curve, which divides any group into five distinct types of behavior. Combined with Lippitt-Knoster, you can get an indication of who will be the first and last to adapt to a new way of digital working. An innovator only requires some skills to participate to overcome anxiety. Early adopters are typically satisfied if the technology is working and can avoid frustration. They are the typical lead users:

Figure 6.12 – The Lippitt-Knoster model combined with Rogers’ adoption curve and Moore’s chasm

In our transformation, we will be adopting new technology to provide care, but to make that a success, we need care providers to be trained in the use of this technology. That’s where the digicoaches come in – professionals that will guide other care providers in adopting the new technology, mostly by learning that this will lead to better outcomes and eventually a better outlook for the patient. This process will follow the adoption curve, as recognized by Rogers. This curve shows the distribution of perceived risk and subsequent emotions and risk avoidance of people. More perceived risk means a longer time to adapt.

A notorious inhibition point is between the early adaptors and early majority, as described by Moore in Crossing the Chasm. We will come across him again in this book.

In other words, adopting new technology and innovations might be more about behavior than about acquiring (technical) skills, which is the playing field of e-nurses. Make no mistake: the technical skills must be trained too, but it starts with adoption. This is where the following steps take place:

- Use the innovators in the DevOps team, and initially in the start-up phase.

- Use the early adopters as lead users and contact the users in the scale-up phase.

- In the scale-up phase, members of the early majority are instrumental in getting user feedback about their role as digicoaches, which is supported by floor walkers from IT and e-nurses.

Here, we can see the importance of including these roles in our TEC teams. Lead users, digicoaches, and e-nurses (or other medical roles) are crucial to letting the teams adapt quickly to new technologies. Moreover, we can think of these roles as the driving forces in adapting and accepting the technology itself.

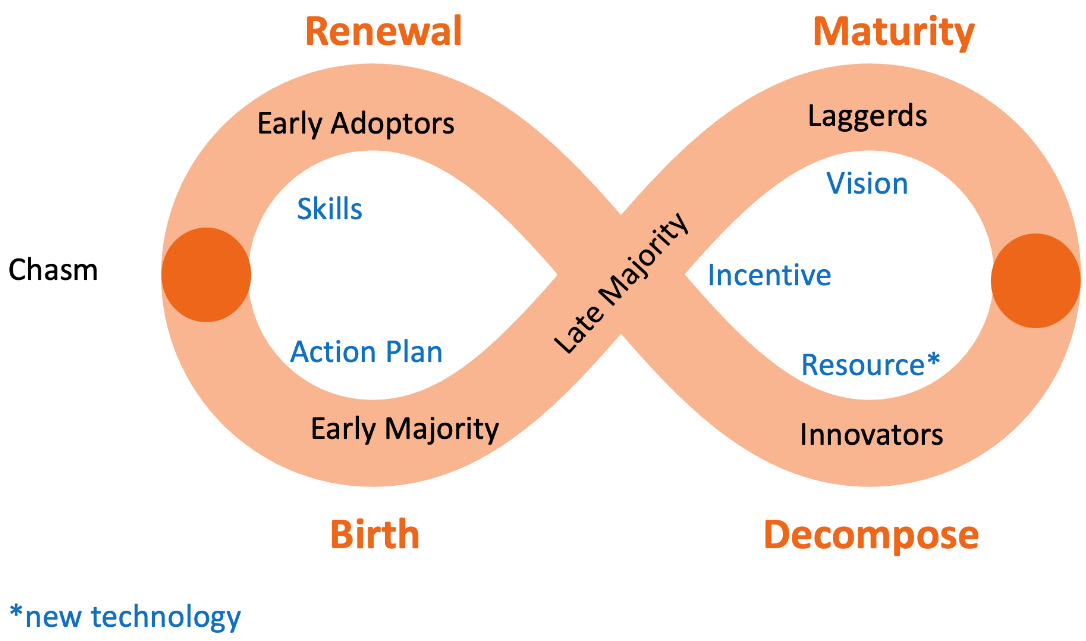

If we combine Lippitt-Knoster and Rogers/Moore, we can define the ecocycle to start understanding behavior in transformation. This is the essence of shared mental models – assessing on what level we are, agreeing upon that, and deciding where we want to go:

Figure 6.13 – Ecocycle combining Lippitt-Knoster and Rogers/Moore

The preceding figure shows that only involving innovators and early adaptors will not lead to success. However, new technology can trigger an innovator to come up with ideas. Early adopters can take this idea further once they master the necessary skills. An action plan should be available to overcome the chasm. The late majority and laggards are the people who mostly look at the achieved value and not the technology itself. Therefore, their stories are very valuable indeed.

While listening to these stories, ensure that you get a balanced view of the different people and their state of risk avoidance, learning, and circumstances, for health professionals as patients and next of kin alike. Otherwise, you end up jumping to the wrong conclusions and solutions.

Also, be aware of the Dunning-Kruger effect, in which people (individual treads) tend to overestimate the short-term value of technology and underestimate the long-term value. This makes it difficult to estimate when technology will be adopted at scale. Sometimes, this is called the VUCA world, which stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous. The best remedy we can think of for now is involving the lead users, digicoaches, and e-nurses. They should have a good grasp of the required needs.

By knowing when and how to listen to stories, given the state of mind of the storytellers, we can see the added value of community builders. Where can you find them? Like systems engineers have their INCOSE community, the community builders also have communities. One of them is known as Systems Innovation or Si Network (https://www.systemsinnovation.network/feed). They are an online collaborative platform for systems thinking and systems change. They work to empower the diversity of individuals and organizations in learning and applying systems innovation ideas and methods toward tackling complex challenges. This also applies to the healthcare sector and helps medical staff, management, and engineers.

Before starting the transformation, be sure that the task force taps into this community.

Summary

We have to agree on a common goal and a model for how to reach that goal. The challenge is that circumstances constantly change at different speeds. This is what panarchy is about: it describes how economic growth and human development interact and depend on ecosystems. In this chapter, we applied the principles of panarchy to the development of healthcare using ecocycle planning. These ecocycles help us take the subsequent steps on our TiSH journey.

The challenge in any transformation is that events happen at different speeds. We used the example of adopting technology: introducing a new technology happens faster than how individuals, teams, and organizations can adopt the new technology. Adoption requires planning to help us get where we want to be as an individual, team, organization, or network.

We also learned about inhibition: we can have technological acceleration, but there will be forces that cause inhibition and decelerate the adoption of technology. There must be something in it for individual professionals and, ultimately, for teams and organizations to start adoption. It has to fit their state of mind, both individually and in groups. We looked at the Lippitt-Knoster model for Managing Complex Change and the Rogers adoption curve, which showed that we need to include new roles in healthcare such as digicoaches and e-nurses to become early adopters. They will tell the stories that will feed DevOps.

All this requires a shared understanding of the goals and objectives and the agreed-upon structures that our healthcare teams will work with. Organizing common understanding activities when people are in the right state of mind is the way for the transformation task force to accelerate the transformation and build shared mental models.

In the next chapter, we will build further on these shared mental models.

Further reading

To learn more about the topics that were covered in this chapter, take a look at the following resources:

- Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems, by L. Gunderson and C.S. Holling, 2001

- Evolution of the Platform Organization, by Stowe Boyd, Work Future at https://www.workfutures.io

- Systems Innovation Toolbox at https://www.systemsinnovation.network/topics/7192272