11

Engagement and Use Start a Flywheel

For Web3 projects, the steps of engaging users and then converting them to use the product are closely intertwined in the marketing process. This chapter describes how a potential user who has already discovered a project comes to engage with it more deeply, often by joining a Web3 community. Once this potential user has engaged, the project can retarget them with calls to action (CTAs) to convert them to using products and taking other useful steps to help grow the project. Engagement and use are a chicken and egg. Users who are excited about products often join their communities, eager to help out. Engaged community members reliably serve as beta testers and early adopters for products and features. This chapter also covers the importance of a project's early community to its long‐term success and strategies for how to gather the right members.

Product Websites

To recap, the goal of discovery is to reach a target audience with a brand message. If the brand message is effective, it sends the potential user into the next step of the marketing funnel: engagement. Discovery channels are all the channels where a potential user might first encounter a brand. The most common in Web3 are search, social media, earned media, and events. Then, depending on the channel where the potential user first discovers the brand message, engagement can take place on a variety of channels.

If the potential user is already motivated to find a solution to their problem and therefore discovers the product through Google Search, the next step toward engagement often looks like clicking through to the product website. Using Google Analytics and other tools, marketers can easily measure how frequently people searching for their keywords convert to website visits. The websites with the highest search rankings and descriptions that match what matters to target audiences will yield the most conversions.

If a user first discovers a project on social media, at an event, or through word‐of‐mouth, they may immediately search the project name and visit the website or look up the project on a social media channel. Social channels should be optimized to drive engagements, for example, like following the account, joining another community channel, and visiting the product website. More on this in the next sections. But many roads of discovery lead to the product website, which is the marketer's home turf for driving engagements. The most important engagements for marketers are those that enable the project to reach, or retarget, the potential user again, ideally leading to conversion to using the product. A project's website is the perfect place to accomplish this.

Wherever they came from, once the visitor arrives on the project website, they are greeted with a new set of signals. Unlike the discovery channel where the potential user first encountered the brand message and chose to engage with it, the website is completely under the control of the marketer. If the website doesn't work to convert the visitor to take the desired CTA, there is no faulting the algorithm, journalists who ignore the key message, or the noise in the background at an event. The product website is the marketer's playground, their owned storefront, to express the memetic package of words and images that is their brand exactly how they want, displaying their knife's‐edge message exactly as designed.

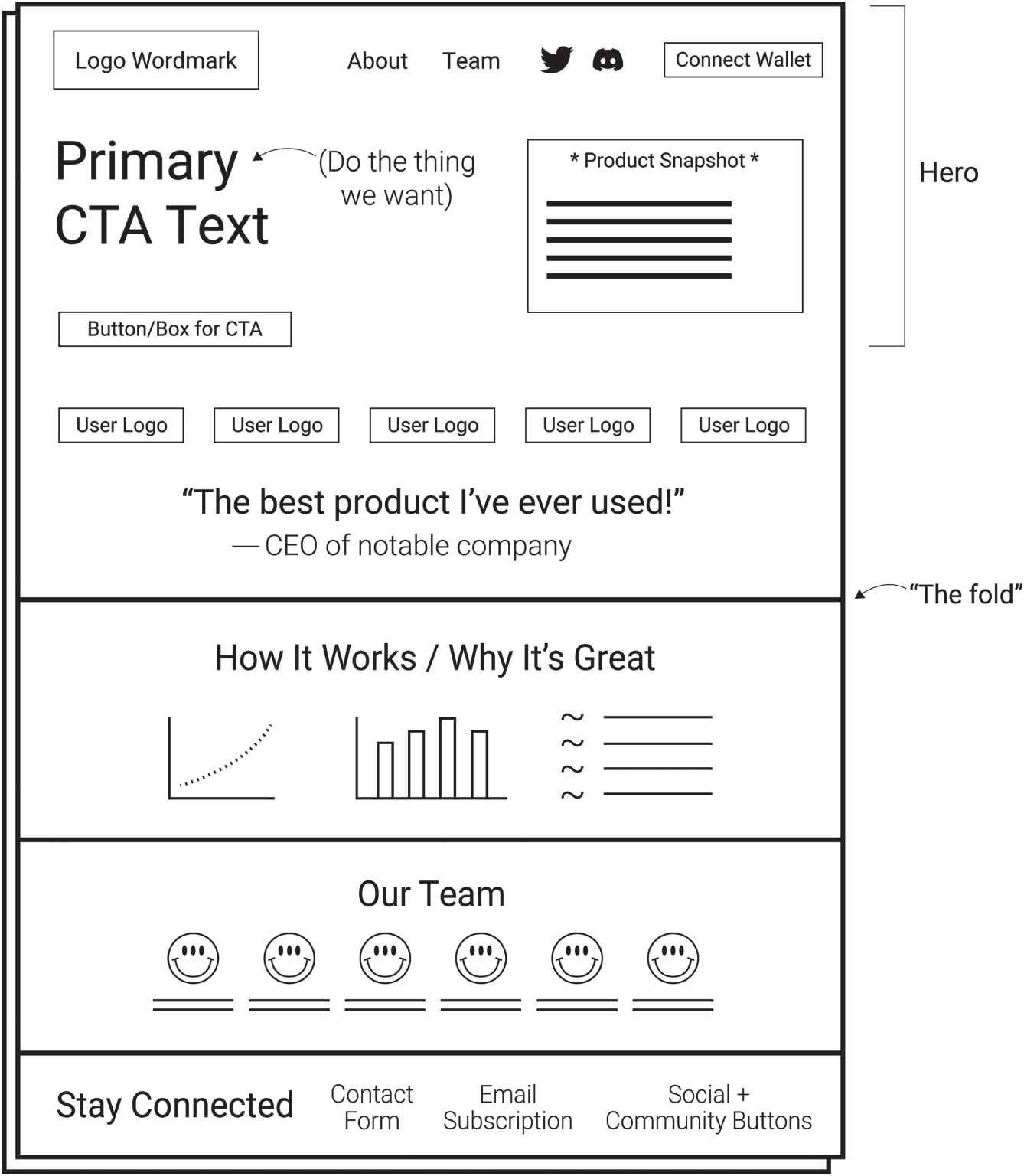

Figure 11.1 mocks up a basic layout for a Web3 product website, indicating placement of key design and marketing elements.

Figure 11.1 A basic Web3 product website

On a product website, the prime real estate is the hero, or what appears “above the fold” before a visitor needs to scroll. Analytics tools generally show that visitors are only willing to scroll so far. The further down the page, the more visitors have stopped scrolling, so the hero is the only section that all visitors see, assuming the website load time wasn't so long that they closed the tab. This happens, and marketers should assiduously work to avoid it; most visitors are ruthless and will only wait a fraction of a second for a page to load.

Each element on a product website should occupy this prime real estate directly in proportion to the importance of the CTA to the success of the project. Ideally, marketers should identify a single primary CTA, and this should occupy the largest and most important position on the hero. Some examples of Web3 projects' primary CTAs to convert to use are “Sign up for the beta,” “Register for the whitelist,” “Download x,” or “Join the DAO.” The CTA is often near the key brand message. Often there is a product screenshot to the right or left of the primary CTA, which ideally signals to potential users that the product has an easy UX, increasing the chances of conversion into use. Marketers can use analytics tools to A/B test website copy and images to maximize the chances of conversion while being careful not to implement language—even if it converts the best—that doesn't tightly match the primary value proposition of the product; otherwise, users may convert to use originally but then fall out of the funnel at the stage of retention, disappointed that the product doesn't solve their problem.

Although the primary CTA should get the most prominent placement on a product website, the hero can also feature other, secondary CTAs. On the top right often are buttons that link to Twitter, Discord, or any other social and community channels the project manages. Dapps often place buttons for users to connect their Web3 wallets in the top right‐hand corner. On the top‐left or center is usually a navigation bar with headings such as “Team,” “Blog,” “About” or “How it works” and sometimes the name of a token or product feature with more information about it. Sometimes these are connected to dropdown menus. To optimize for discoverability on search, these headings can be named after the most frequent search terms for the project. Some projects also have sign‐up boxes for email newsletters. For projects that haven't launched yet, an email sign‐up box can be the primary CTA, allowing the project to retarget potential users when a product beta or token becomes available. Marketers should make sure to include key CTAs in the hero section. Less important CTAs, along with more detailed information for more motivated visitors who want to learn more, can occupy lower sections of the page that require the visitor to scroll.

Web3 marketers may or may not choose to implement Google and Facebook tracking pixels on their websites. When our department at ConsenSys first met with the team at Truffle (the leading Ethereum development framework within the ConsenSys mesh), we presented a number of ideas to help Truffle better understand its audience and how well its website was working. Truffle was excited about our presentation but hesitant to add tracking pixels to their website, a step that seemed obvious to members of our team trained in Web2 best practices. Truffle was ideologically opposed to the Web2 practice of surveilling users and refused to add the pixels, even if they could help increase their user base faster, which was their primary business goal. We didn't push back. Instead, our marketing team learned something about our audience that day. The developers who were Truffle's target audience disliked the practice of collecting data on users. Any website visitor can easily click “inspect element” or “view source” to identify a tracking pixel in the page's HTML. Although probably only a small minority of visitors would actually refuse to use the product due to the pixels, or worse, vocally complain on social media, at that point in the history of Web3, those ideologically driven technologists were our key target audience, those most likely to become Truffle power users. The brand risk of implementing a pixel wasn't worth the potential benefits to user growth.

Though Truffle may or may not use tracking pixels on its website today, we still periodically encounter teams who wish to refrain from using Web2 marketing technologies, especially for user data collection. For example, at Serotonin we worked with Orchid, a Web3 VPN. As a privacy tool, they wished to target audiences concerned with online privacy, who are also more likely to inspect a page's HTML. Implementing tracking pixels was out of the question; we would develop novel methods for monitoring our marketing funnel. Sometimes this means finding alternative A/B testing and analytics tools, such as Matomo, which offer some data while respecting user privacy. But the lesson broadly applies to Web3 marketers who must be flexible, pay attention to audience preferences, and not overly depend on practices from Web2.

A good product website evolves alongside the product. We recommend Web3 projects publish a simple splash website as soon as they have determined their visual and verbal branding, knife's‐edge key message, and primary CTA. A prelaunch project's primary CTA catches the potential users who discover the project on various channels and are willing to engage, in a holding tank, allowing the project to target them again later when it's ready to convert them into use. Without a CTA in place to act as a holding tank, projects may drive discovery through channels such as social media, search, at events, or through word‐of‐mouth, but all these activities will be inefficient at producing ROI for the project because the energy can't be captured anywhere. Without driving toward a backstop that can capture interest, usually a product website with a CTA, top‐of‐funnel marketing activities are basically useless.

Between launching their website and social channels and actually launching their products, projects should concentrate on growing their owned audiences on social media and community channels and email newsletters. They should use these channels to keep their engaged communities up to date on progress with their products, sharing information about their teams and the technology they are building, including any announcements, events, partnerships, funding rounds, or asks for the community to get involved, such as with community management or a bug bounty program. Once a product is live, the project's website needs to change its primary purpose from funneling engaged potential users into holding tanks to be reached later for conversion into use, to converting visitors directly into using the product. It's time for the website's primary CTA to shift.

Marketers designing product websites should keep in mind that they're still fighting against the forces of indifference, inertia, and skepticism at the engagement stage of the marketing funnel. Just because a potential user has arrived at the website doesn't mean they will convert. The content of the product website needs to convince them to answer the call to action. Potential users are always wary of new, less‐established projects, especially in a sensitive space such as Web3, where connecting one's wallet to the wrong dapp or sending crypto to the wrong address can result in hacks or value being permanently lost. The content of the website must include knife's‐edge messaging to dispel indifference by convincing the potential user they really have a problem, and inertia by demonstrating the product is the best solution. It must also assuage skepticism by reassuring the potential user that others like them are using the product; that the product is endorsed by trusted third parties like notable investors, partners, and code auditors; and that it's been proven over time with a history of use.

The “wall of trophies” and “instant incumbency” strategies that follow have worked for Web3 projects. They may or may not work for you. Whether you decide to use or adapt these—or develop your own—should depend on first knowing your audience.

Wall of Trophies

The wall of trophies tactic pairs well with the Chainlink strategy. As early as possible, projects should strive to attract users who resemble the users in the broader audience they want to target. They should broadcast these partnerships using the Chainlink strategy, harnessing them to drive top‐of‐funnel discovery on search and social, and also showcase their partners' logos prominently on their websites, sometimes even in the precious hero section near the primary CTA. Website visitors who see the names of prominent users—perhaps companies just like theirs, or larger and more notable ones, or well‐known individuals who use the product—will be less skeptical and more likely to take the CTA.

If no comparable companies or individuals use a product, a potential user takes a longer path toward use stymied by more inertia, because they need to either do research for themselves or, if they represent a team, generate a detailed argument to convince colleagues that the product is right for their business. A prominent wall of trophies enables many potential users to skip this time‐consuming step and convert directly into use or another CTA. If a project sees that its competitors are already using a tool, this can be even more compelling, because it doesn't want to miss out on an advantage.

Walls of trophies can take many different shapes. For some projects, the trophy to display isn't partnerships with other companies, it's metrics like total value locked (TVL). The mechanism is the same. A DeFi protocol with high TVL demonstrates to a new potential user that other DeFi users just like them are willing to deploy their funds in this protocol. For this reason, DeFi dapps and liquidity pools often prominently showcase these types of metrics near their primary CTAs.

The EEA website we launched in February 2017 was a simple splash page with a logo, key message, and a social button to follow on Twitter. The most prominent image in the hero was a wall of logos that included Microsoft, Intel, JPMorgan Chase, Accenture, and more. The primary CTA was an email capture bar to submit a request to join the EEA. Many companies large and small filled out the form, and soon the EEA had a long list of qualified leads waiting to join the organization.

Projects of all sorts and sizes shouldn't hide their users under a bushel. Instead, they should feature walls of trophies on their websites, the logos of their most valued partners, cutting through blocks of skepticism, indifference, and inertia to drive conversion.

Instant Incumbency

Because of the risks inherent with Web3 dapps, potential users are often wary of new projects and companies. It doesn't help if their teams are populated by pseudonymous Twitter accounts, especially if the accounts have few followers. In combination with the wall of trophies and Chainlink strategies, new projects should consider the approach to their brands that we call instant incumbency. If a project is competing with larger, more established incumbents or institutions, it helps to look legitimate. That means adopting the visual and verbal style of more established competitors into their brand look and feel, perhaps with a modern touch unique to the project's new brand that helps it stand out against the background of what the audience expects. A brand that feels like an incumbent overnight isn't an exact copy of another brand; it needs its own twist, but it can take inspiration.

Marketers should pay attention to any channels or interaction points between potential users and the brand that consciously or unconsciously signal that a brand is small and new. For example, when I joined ConsenSys, which was at the time small and new, our website, blog content, and even automatic signatures on employees' email included detailed descriptions of what ConsenSys was. This sent the message to potential audience members that we didn't expect people to already know about ConsenSys. With all we were doing to build Web3, our team knew ConsenSys was positioned to become a significant technology player. We would get there faster if potential partners, especially at large institutions, saw us as a more mature and established company.

Our team removed any language that suggested to counterparties that we assumed they weren't familiar with us. We still featured an “About” page on our website where visitors could read about ConsenSys, and we included the standard blurb at the bottom of a press release with language about the company; our goal wasn't to prevent new visitors from learning about ConsenSys. But we consciously stopped presenting ourselves as a startup that people probably didn't know. Once we scrubbed these explanatory lines from all the channels where they existed, when new target audience members discovered our brand for the first time and didn't recognize it, they assumed the error was on them. I think they wondered, “How could I not have heard of ConsenSys?”

Some Web3 projects, such as those that emerged during DeFi foodcoin summer, intentionally brand themselves as being new and exploratory. Their websites featured a 1990s vaporwave aesthetic, cartoons, and cat memes. These brands were perfect for the mostly young, often technically proficient risk‐takers who identified themselves as degens. Here the “instant incumbency” mindset wouldn't have worked. Every project should construct its brand and key assets like its website out of a deep understanding of their target audience and what matters most to them. At Serotonin, our process for working with a new project always starts with building a visual and verbal brand, the foundation of any further marketing efforts, based on our understanding of their target audience. A high‐quality brand, defined as matching its audience, increases the likelihood that engagements will convert into use.

Fostering Community

After a new potential user discovers a project, they may decide to engage with it by visiting its website. Alternatively, they may visit its social media account. When the new potential user arrives on the social channel—let's say a Web3 project's Twitter page—without necessarily consciously thinking about it, they perceive from the size of the project's following whether it's large and established, with many community members, or whether it's small, new, or unable to attract a following. Pushing against the headwinds of indifference, skepticism, and inertia, they may decide to follow the account if they think the content is interesting or want to hear updates from the project. The new potential user might click through the links in the Twitter bio and arrive at the project's website, a collection page on an NFT marketplace like OpenSea, or another location where they could be converted via CTA to make a purchase or use a product.

They also might click links in the Twitter bio that send them to the project's community channels. These are simply communications platforms where members of a Web3 community may gather, not to be conflated with the overarching idea of community in Web3, which refers more abstractly to the group of people connected with a Web3 project, who may or may not have joined a particular platform. For most Web3 communities, these platforms are Discord and Telegram. Slack, WhatsApp, and others are used also, but less frequently. The reason Discord is so popular with the Web3 community is that it was early to implement plugins that connect with Web3 wallets. This enables Web3 projects to spin up Discord channels and make them available only to holders of a particular fungible token or NFT or a certain quantity of that token. For many of the most popular NFT collections, these token‐gated communities are the invite‐only members clubs of the internet, each behind a different velvet rope, with its own custom criteria for entry. Inside them, members access updates from project teams, exchange information and ideas, get to know and trust each other, organize events and meetups, contribute to projects, and form new ones of their own.

The concept of community in Web3 can sound annoyingly high‐minded or abstract to outsiders, but it actually means something specific. It refers to the single category that forms when a Web3 project collapses those of investor, builder, and user into a single economically aligned group. Participants in this group contribute to the project fluidly and in self‐defined ways, sometimes contributing to its code base, answering a challenge or participating in a bug bounty for a reward, and sometimes deploying capital into the project. Their incentives can run the full gamut from extrinsic to intrinsic. Some communities are primarily social groups that offer participants a sense of identity and shared purpose.

For example, Friends With Benefits is a token‐gated community on Discord that requires 75 FWB fungible tokens in a Web3 wallet to join. Its members, generally Web3 enthusiasts in the cultural sphere of arts and entertainment, organize parties and get‐togethers, share new projects and job opportunities, or exchange “alpha”—scoops about trading tokens or NFTs. A different example: the well‐known NFT project Bored Ape Yacht Club has a Discord server for its community. Some channels on their Discord are open to the public; others are token‐gated and visible only to holders that connect their Web3 wallets and verify that they own a Bored or Mutant Ape. Similarly, these members are sharing insights and answering each other's questions. They gain special early access to information about the project and are in direct contact with its founders and leadership.

Indeed, in the largest and most established communities, project founders are actively engaged, making themselves visible and available. Even celebrities launching NFT collections should make themselves regularly available to their communities. Authentic and regular access is one of the perks Web3 audiences expect. Serotonin worked with Pace Gallery, one of the largest art galleries, to launch a Discord community for their NFT platform just as it was about to launch an NFT series by Jeff Koons, one of the world's most famous living artists. To their surprise, we insisted that Koons himself do an AMA (“ask me anything” session) on Discord and engage directly with the community there. This project also shows that access, although important, doesn't have to be extreme: Jeff Koons didn't have to be available on Pace's Discord around the clock, but his AMA engaging directly with the community there—on their home turf, as it were—demonstrated his (and Pace's) sincere commitment and interest in Web3.

Considering what these communities offer, the notion of community in Web3 is more profound than it originally appears. Our atomized, individualistic culture can be painfully lonely. Many of us felt this way especially during the pandemic. As we enter a world in which our physical reality is more constantly mediated by and enmeshed with digital reality, it's easy to assume that we'll be driven further apart. However, this isn't necessarily true—Web3 offers us new structures to come together. These communities are an early example of a new type of structure, a unit for both group sense‐making and economic survival.

The formation of Web3 communities is philosophically fascinating. Almost every technology that has made the most impact on humanity has allowed people to collaborate in larger groups, and Web3 is no exception; Web3 communities and DAOs demonstrate this point. But when it comes down to actually managing Web3 communities on platforms such as Discord and Telegram, we come back down to earth. These communities require granular day‐to‐day operations to get off the ground and then continue to thrive and grow. Communities on Discord meet regularly on weekly or monthly phone calls, during which project leads usually update the group on progress and road map. Most DAOs have their own communities on Discord whose members are the members of the DAO. These DAO communities participate in similar activities, but they also use the channels to discuss their votes on investing opportunities and new members.

In the context of the marketing funnel, the CTA to join the community usually appears at the engagement stage: it can be a primary or secondary CTA on a product website or a CTA on a social media account. On the shallowest level, community channels, like social media channels, function as holding tanks for potential users who are willing to engage, enabling projects to continually retarget them with CTAs to convert to using a product. Although this framing makes sense in a Web2 context, it's far too reductive a way to understand how communities function in Web3. The community isn't a group waiting to be marketed to by the project; they become part of the project themselves. In Web3, the marketer merges with the community, the community with the marketer. We all become one.

But nirvana isn't achieved overnight. Before launching a community channel, projects should make sure they are configured and staffed properly. The day‐to‐day of Discord channels is often run by pseudonymous mods (moderators) who can be anyone, at any level of seniority. Especially at first, team members should plan to make themselves available to be mods. Third‐party community moderation services exist, and they are better than nothing, but really, we tend to recommend the team behind the project be the ones moderating the community. They can hire teammates from firms with this experience, but from the perspective of the newly forming community, it should be run by its own team. As the community grows, project teams sometimes offer the most engaged community members incentives to begin serving as mods themselves. This is especially helpful to projects that attract global communities and therefore look to secure 24/7 coverage.

It's important for projects to let communities do their own thing. Members will set up their own subchannels and launch their own conversations. Marketers should pay careful attention to see what their communities do organically that works in service of the project's success. Then their job is to fan those flames, as in our examples of Crypto Coven's “Web2 me vs. Web3 me” campaign and Moonbirds supporting the emerging Ladybirds subcommunity. These projects noticed their communities were doing something helpful and, instead of clamping down and insisting all ideas need to come from project headquarters, offered these self‐organizers the resources and authority to grow the movement in their own direction. This is exactly what we did early on at ConsenSys, organizing a network of Ethereum meetup leaders and providing them with content and resources.

On the flipside, it's important not to let things get too out of hand. It's contingent on community mods to clearly set the rules—usually on the #general or #welcome channel that users first see—and enforce them, sometimes even banning members. If a community channel becomes all speculators talking about price or starts violating community standards for behavior with inappropriate content, it becomes a place where target audience members don't want to live.

The Community Spaceship

It matters a great deal who a community's first members are. They disproportionately set the tone for the rest of the community that forms. Once a community grows to a certain size, the original project team effectively loses control over the tone of the community and whether their target audiences will want to join it. The early days when they are in control is the time the project team can make the most impact by curating members. A good analogy for starting a Web3 community is an alien arriving on a spaceship, sending down a ladder somewhere, having humans climb the ladder and board the spaceship, then flying back off into space. The aliens are then stuck with those humans on a spaceship forever. Where should the aliens let down their ladder? What kinds of humans do they want on their spaceship? Given the long‐term consequences, the aliens should consider carefully before arriving on earth. The stakes are high: getting the right community members is far more important than community size at the start.

Most projects' ideal community members aren't just in it for rewards; they can be interested in the technology generally, using the product, contributing toward a larger mission or set of values, or connecting with others. Some communities, however, are explicitly economically driven, such as the DAOs that make governance decisions for a DeFi protocol. It can be essential in this context that community members practice rational self‐interest and discuss tokenomics and math. The tone and content of the MakerDAO Discord server will be different from that of Bored Ape Yacht Club's. If a project has a token or NFT associated with it, all the holders of that token are generally considered community members, and many elect to join community channels like Discord to connect with people with similar interests, stay informed about the state of their assets, and contribute where they can to the project's success.

Who holds a project's token and their incentives to buy and sell the token can impact short‐ and long‐term token price. If a project distributes tokens to people who don't care about the project, those people will most likely sell them, and without sufficient buy pressure, the token price will collapse. However, if a project distributes a token by a mechanism such as retroactive distribution proportional to community members' history of using the product, those members are more likely to retain the tokens, join and participate in community channels, and continue using the product.

Where Web3 projects find their earliest community members and token holders can determine the fate of their projects. For most projects, the ideal is growth over time as the project builds and executes its road map, adding on new fundamentals and markers of success. Airdropping tokens to anyone who performs a certain action can generate large communities or social followings overnight, but this and other, similar short‐term tactics can lead to long‐term struggles with community tone and token price. Similarly, projects that buy followers or community members can expect them to be mercenary. The best way for Web3 marketers to attract community members is to clearly present the value proposition of their products and communities with knife's‐edge messaging, ensure that messaging gets discovered on top‐of‐funnel channels, and deliver against their promises.

At Serotonin, we usually suggest Web3 projects form communities before they launch a token or NFT collection. That way, there is already pent‐up demand for the product. Bootstrapping a community before launching a token gives project founders the opportunity to test whether target audience members are receptive to their value proposition, and to tweak that value proposition until they find a fit with an audience. They should continue to iterate their offering until they're sure that their community will be receptive to it, never hesitating to ask their community members directly, Would you be interested in x? or, What would you change about y? Projects can learn a great deal from their early communities to increase the chances that launches and drops achieve their goals.

We also often recommend that new projects offer their early communities value in a Web3 context before asking them to pay for something. This helps build trust and attract the types of community members who are interested in the actual project. One example of perfect execution of this strategy is the NFT influencer Gmoney, who whitelisted the wallet addresses of people who had attended certain conferences based on the POAP tokens in their wallets (proof‐of‐attendance protocol, a protocol that generates tokens that prove someone has attended an in‐person event), and allowed those wallets to claim an Admit One pass, an NFT that enabled them to access his token‐gated community channel on Discord. A whitelist, sometimes called an allow list, is a pre‐vetted list of public wallet addresses that are allowed to perform a particular action on‐chain, such as claiming a claimable. Admit One community members on the Discord server received direct access to Gmoney and information about the project. Because of Gmoney's reputation for good taste in NFTs and supporting NFT communities, the Admit One NFTs quickly became valuable, sometimes priced as high as $15,000, even though he originally gave them away for free. It was only after building this goodwill on top of his strong existing reputation that Gmoney launched his NFT fashion line, 9dccxyz, whitelisting Admit One NFT holders for early access to purchase items from his collection.

Building community first, and giving away items for free to start, may sound overly generous or like too much prework before starting to capture revenue—at least to those with a Web2 mindset looking to round up “consumers” and charge them money. There is, however, a strong logic behind the practice. Even if a Web3 project doesn't immediately profit financially from its first community formation efforts or its first token or NFT launches, it has still performed an economically valuable activity by establishing an on‐chain history of wallet interactions with the project. These wallets can be retargeted indefinitely and become the marketer's dream for customer relationship management (CRM—for more on which, see Chapter 12 on retention) and over time, put the project in a position to perform a retroactive distribution to token holders already proven to like using the product, people who would be more likely to buy or hold than sell. Though early Web3 community‐building strategies can sound counterintuitive at first, marketers should keep in mind the North Star of building a healthy community that grows over time.

Content

Marketers must be able to furnish their chosen channels with content. On social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram, that can mean custom images. On YouTube and TikTok, that means videos. Before marketers spin up a particular channel, they should make sure they have engaged the correct staff, either internally or through agencies or partnerships, to ensure the channel stays active with a regular cadence of publishing new content. Nothing looks worse to a visitor than an empty channel with no posts, engagements, or followers, or one that posts inconsistently with an irregular voice and message.

Marketers shouldn't launch channels until they have the proper staffing in place and a future‐looking content calendar so the team always knows what content will be published around the corner. The marketing team should set objectives and key results (OKRs) for content performance, not focused on publishing a certain amount of content per time period, but on the outcomes produced by the content (for greater detail, see Chapter 8, “Set Key Metrics”). A few examples of outcomes content can produce are: an x% increase in website traffic, y number of social media engagements on a post, or driving z number of qualified leads into an email capture. The content itself, whether it's in the form of social posts, blogs, op‐eds, industry reports, or event presentations, should be closely tailored to fit the interests of its target audience and reiterate key brand messaging. Reiterating this messaging in blog posts helps websites gain domain authority and rank higher on search, even if not every post drives a massive amount of traffic. Projects should ensure that they publish blog content with each of their main keywords in the title to increase the chances that they rank for those terms (for more on blogs and search ranking, see the “Search” section in Chapter 12). The more relevant the content is to its target audience, the more they will open and share, compounding the benefits of discovery.

Once target audience members sign up for an email list, join a community channel, or follow a social media account, the project is in a position to continuously reengage them with content, including CTAs to start using a product or try out a new feature. Social media platforms are mostly algorithmic, which means projects can't reach their full audiences at will with new content. On a community channel or email listserv, there's less intermediation, and marketers can decide when they want to share content, as long as audiences will pay attention. We typically recommend, if projects have the staff to create and distribute emails, and if the channel makes sense for their audience and business goals, that they spin up email marketing. Discord or Telegram could suddenly disappear. The Twitter algorithm could change one day to privilege certain types of accounts over others. And certainly, MailChimp and other email platforms could have problems, but there's nothing more dependable than a spreadsheet with the addresses of audience members who have agreed to receive emails. Email is one of the few channels a project can truly own, and it can become an excellent way to distribute content.

Content and email newsletters don't always need to convert users to using a specific product; they can be helpful for building a store of goodwill that can later be used toward converting users. Early on at ConsenSys, we didn't always have a product or token launching, but we realized the burgeoning Web3 community needed a regular source of updates about everything being built on Ethereum. Our marketing team began writing a regular newsletter, and our email list became a destination for anyone curious to learn about the Ethereum ecosystem, not just those who wanted to receive product marketing messages from ConsenSys. When we did have a product to market, we were able to reach a larger and more engaged audience because of all the time we'd spent building credibility and adding editorial value in the past.

Content can be a godsend for projects that haven't yet launched their products. When projects come to us at Serotonin, they often want to start building social followings and communities, but they aren't sure what to say to them without having a product actually live yet. The answer is content. Prelaunch projects should think of themselves as niche content brands. A Web3 privacy project can spin up a blog series and newsletter about Web3 and privacy. A prelaunch DeFi protocol can create educational content about how newcomers can start using DeFi. A woman‐led NFT collection can publish lists and analyses of the best women‐focused NFT communities or create a network of other women‐led NFT projects and cross‐amplify each other's content on social media. If projects generate demand through content and concentrate it on specific channels, when they are ready to launch products, they need simply to open the floodgates. Content‐focused marketing activities can and should start long before launch.