Tax considerations are a critical part of organizing a business. The cost of operating a business, from setup fees to legal expenses, can ultimately be dwarfed by the effect that taxes have on how much money a freelancer gets to pocket. This chapter introduces some basic concepts about business taxation. Tax is a large and byzantine topic, one that is mostly beyond the scope of this book. The goal of this chapter is to touch upon some basic topics that might factor into your decision about how to structure your business, so you can do further research on areas of particular relevance to your situation. Readers should note that as this book was going to press Congress was debating significant changes to the way business income is taxed. The values and examples in this chapter can help you come to grips with important tax concepts, but many of the specifics may be changing soon.

Obtaining a Federal Tax ID Number

Every small business should have its own IRS employer identification number, or EIN. The IRS offers a fast, free online system for obtaining an EIN,1 or you can fill out Form SS-4 and submit it by fax or mail. The EIN is unique to your business and helps the IRS link up your business’s taxable events to the business and ultimately to you as the owner.

One good reason to get an EIN is to avoid having to disclose your Social Security number to clients. Chances are that every business client will ask for an IRS Form W-9, on which you can provide your Social Security number or, alternatively, your EIN. Businesses that pay contractors $600 or more in a year are required to report the payments on Form 1099-MISC, which includes the contractor’s tax ID. You’ll receive a copy of the 1099 from the client and will report it as part of your annual tax return.

State Franchise Taxes

States usually impose taxes other than income tax on business entities. An important one to know about is franchise taxes, which can be a flat fee or can vary depending on the company’s income. Franchise taxes can be an ugly surprise, in part because they aren’t subject to the sort of deductions that are available in the income tax world. For example, California imposes a minimum franchise tax fee of $800 on all LLCs and corporations doing business in the state.2 Texas does not impose franchise taxes on businesses with less than $1,100,000 in annualized revenue, but businesses below the threshold must file a No Tax Due Report with a total revenue figure and other details.3 Know your state’s requirements before you decide what kind of entity to form.

Employment Taxes

Freelancers who are used to working for an employer may be surprised to learn just how expensive employment taxes can be. In federal terms, “employment tax” means a combination of two taxes on wages: Social Security (in 2017, 6.2 percent paid by both the employee and the employer, for a total of 12.4 percent of wages) and Medicare (in 2017, 1.45 percent paid by both the employee and the employer, for a total of 2.9 percent of wages); these two taxes combine for a 15.3 percent tax rate on wages in 2017.4 In 2017, the maximum wages subject to Social Security tax is $127,200; there is no equivalent cap for the Medicare tax.5

Your state may collect other kinds of employment tax as well. Ordinarily, both the employer and employee pay the tax on the salary paid to the employee, but only the employer gets to claim employment taxes as a deductible expense. In a self-employed situation, you will still be able to deduct half of your employment taxes, but the math can be more or less favorable depending on how your company pays you and how your company is treated for tax purposes. A bit later we’ll look at an example of how this could play out.

Income Tax Treatment of Business Entities

For federal income tax purposes, one can think of the business structures discussed in this book as falling into two categories: pass-through or tax-regarded. Each of these categories is defined by how tax authorities treat the business and its distributions to its owner.

Category 1: Pass-through Entities

In a pass-through business structure, the owner (or owners) of the business report the company’s income and losses on their personal income tax returns on IRS Schedule C. The business entity is disregarded for federal income tax purposes. Sole proprietorships, which have no formal existence apart from their owner, fall into this category. Partnerships and LLCs also receive this treatment by default, though they can elect to be treated as a tax-regarded entity (see below) by filing the appropriate election with the IRS and, quite often, state tax authorities. Conversely, a corporation must choose to be treated as a pass-through entity, otherwise it will have to pay separate income taxes.

Keep in mind that an entity being pass-through doesn’t free it from filling out paperwork; every business entity, even pass-through entities, files forms with the IRS at tax time. This ensures that the IRS knows what to look for on the owners’ personal returns. Federally disregarded entities can also be subject to other kinds of tax that don’t get passed through to their owners, such as employment, state, and local taxes. For example, California collects a 1.5 percent income tax from S corporations.6

Category 2: Tax-Regarded Entities

A tax-regarded business entity files its own tax return and pays income taxes on any money it earns, applying corporate income tax rates. By default, a corporation is treated as a separate taxpayer from its shareholder. An LLC can elect to be treated as a corporation by filing an election with the IRS. Any earnings the owner receives from the company are taxed again at personal tax rates. This is often described as double taxation, because both the company and its owner are paying income tax.

To reiterate, here’s a quick summary of how these categories break down for the most likely business forms for freelancers:

The Potential Benefits of Tax-Regarded Entities

At first blush double taxation sounds bad. The government takes a cut of whatever revenue the company earns, and takes another cut of what the freelancer takes from the company as earnings. Nonetheless, operating a tax-regarded company can be preferable in certain tax situations, especially in businesses with high income. There are several basic reasons for this.

First, a tax-regarded entity can claim a tax deduction for salary paid to its owner-employee. The IRS permits entities taxed as corporations to deduct salary only if the salary is not “excessive.” To determine whether the salary is excessive, the IRS will look at a number of factors, including typical salaries of comparable professionals. Any salary paid in excess of this amount will be treated as dividends. Unfortunately, the IRS doesn’t have strict guidelines on what qualifies as “excessive” salary, so if you expect to be a high income earner, it is worth consulting with a tax adviser to figure out what makes sense for your situation.

Second, dividends are not subject to employment taxes. Although dividends are not deductible expenses for a tax-regarded entity, they are also not subjected to employment taxes. Using the dividend approach, the company must pay its employee-owner a “reasonable” salary, essentially according to the same vague rules used to identify “excessive” pay. Then the company, following the requirements of the company’s organizing documents and state law, declares a dividend, distributing its surplus to the shareholder as a return on the shareholder’s investment in the company. The owner pays ordinary income tax on the resulting payment, but avoids the employment tax hit.

Dividends are subject to a number of technical requirements that must be followed to avoid the IRS treating them as taxable salary. First, they need to be formally approved by a written consent of the company’s management, that is, by a corporation’s director or by an LLC’s member. Skipping this step and simply transferring money from your company’s account to your personal account will look like ordinary salary; going back to paper over these transfers can be considered fraud. Second, dividends normally can only be declared if the distribution to the owner will not cause the company to become insolvent, that is, the company’s debts won’t exceed its assets after the dividend is paid. This can be trickier to determine than it might seem. Because of these technicalities, freelancers who want to take advantage of the dividend approach quite often need the help of a tax professional, accountant, or lawyer to make sure everything is done the right way.

A third potential advantage of tax-regarded entities is that they can retain profits for operating expenses. A tax-regarded entity need not pass on its cash to its owner. Instead, it can hold on to its cash and use it for future expenses, like buying expensive equipment. This avoids double taxation altogether by not converting the money into salary or dividends, and avoids employment taxes.

High income earners (roughly speaking, those who earn $100,000 or more annually) would probably benefit the most from having a tax-regarded entity. By taking a portion of profits as salary, and the rest as dividends, the result may be a lower tax bill. There are some expenses associated with doing things this way, such as the need for a formal payroll system, and the increased necessity of professional help, that might make it undesirable for a lower income earner.

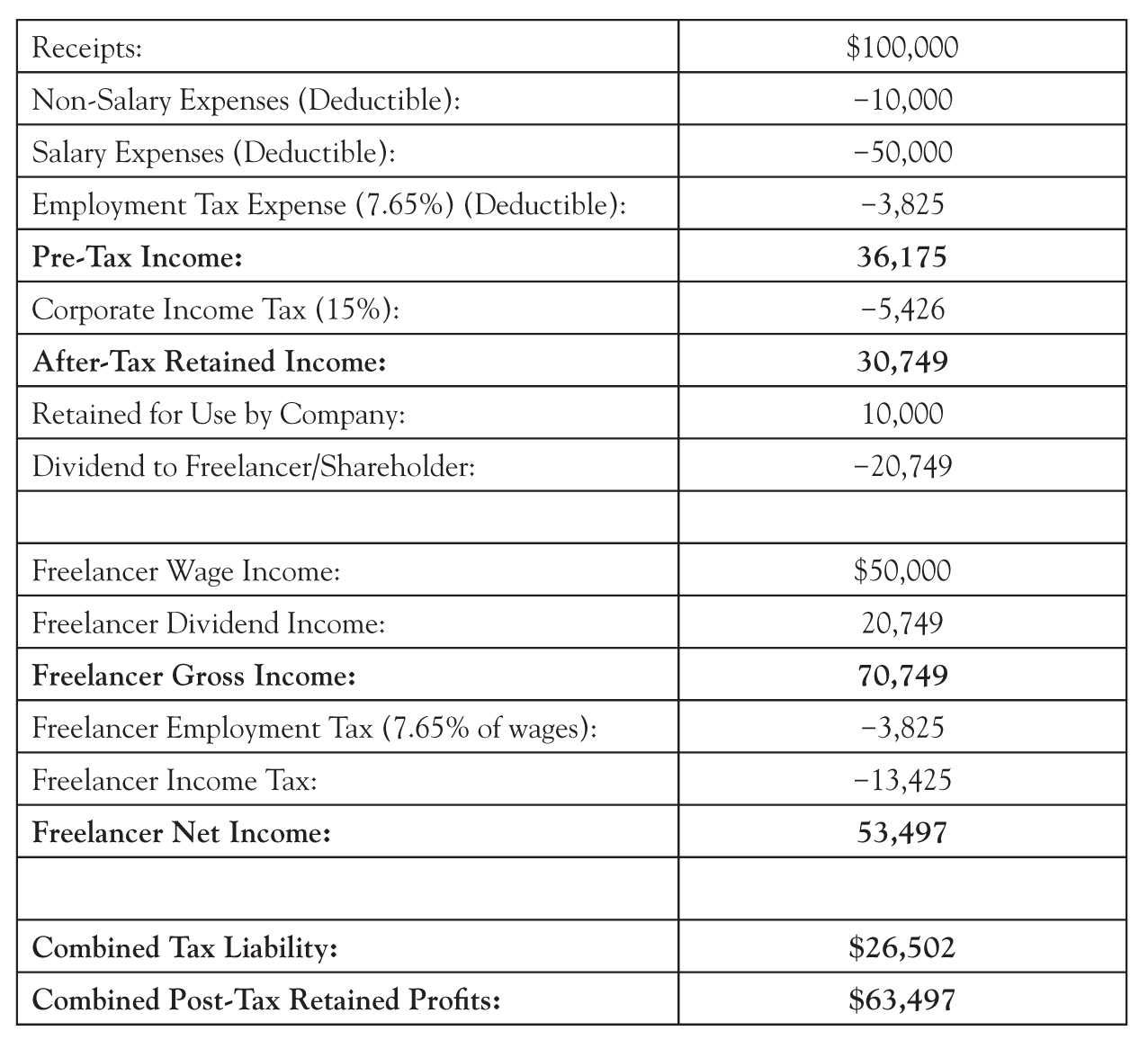

A Tax Example: Tanisha

Here is a simplified example that shows how operating a tax-regarded company might benefit its owner. This example leaves out a lot of important factors that contribute to a calculation of income tax, like standard deductions. The point is to help you understand how “double taxation” might be a net benefit.

Tanisha is a freelance videographer with a corporation, Super Video Inc. Over the course of a year, the company has $100,000 in earnings. The company had $10,000 in unreimbursed expenses for things like phone, Internet, travel, equipment, and professional fees. The example uses the tax rates applicable to a single filer in 2017.

Tanisha may have good reasons for leaving Super Video Inc. as a tax-regarded entity, thanks to the advantages she gains from the relatively low corporate tax rate, the deductibility of wages, and the limited applicability of employment taxes. She pays herself a salary of $50,000, which she determines is about the average for videographers in her area. She plans to use $10,000 of the company’s remaining after-tax profits to upgrade her cameras and lenses, so she leaves that portion in the company’s account and plans to transfer the company’s after-tax surplus to herself as a dividend. Using these figures, the company has a total of $63,825 in deductible expenses ($50,000 in salary, $3,825 in employment tax [7.65 percent of $50,000], and $10,000 in ordinary expenses). This leaves the company with $36,175 in taxable income. The company’s income will be taxed at the corporate tax rate (15 percent in 2017 for federal taxes), leading to a corporate federal income tax bill of $5,426.

After factoring out $10,000 to be retained by the company for future equipment purchases, Tanisha puts on her director hat to sign a short written consent authorizing the company to pay her a shareholder’s dividend of $20,749, representing the remaining surplus profits for the year. On her personal tax return, Tanisha pays the other, nondeductible half of the employment taxes on her $50,000 salary (again, $3,825, or 7.65 percent of $50,000) and personal income taxes on the $50,000 salary plus $20,749 in dividends. Tanisha’s tax rate tops out at 25 percent, which results in a personal income tax of $13,425.7 Tanisha’s bottom line for the year is a net personal income of $53,497, with $10,000 retained by the company, and a combined tax bill of $26,502.

If, on the other hand, Tanisha has properly filed a Subchapter S election to have the IRS treat Super Video Inc. as a pass-through entity, the tax treatment is quite different. Because Super Video Inc. is an S corporation, it does not pay dividends. As a technical matter, S corporations pay distributions to their shareholders, who must report their allocation of the company’s net profits and losses on their personal income tax returns regardless of whether they actually receive payments from the company. This means that Tanisha reports all of the company’s earnings and losses on her personal tax return, so it will not save her any money to retain cash at the company. As a starting point, she has earned $90,000, or the company’s net receipts ($100,000) less its ordinary expenses ($10,000). She must pay both her personal half and the company’s half of the employment taxes due on this amount (15.3 percent of $90,000, or $13,770). She gets to deduct the business’s half of this amount, $6,885, from her $90,000 income for calculating her personal income taxes, netting her an adjusted gross income of $83,115. Her personal income tax on this amount is $16,517, leaving her with a net personal income of $59,712 and a total tax liability of $30,287.

Is your head hurting yet? Here’s a summary to help you sort out the numbers:

Tax-Regarded Entity (C Corporation)

Pass-through Tax Entity (S Corporation)

In this example, Tanisha saves more than $3,700 in taxes by operating as a tax-regarded entity, thanks to three things. First, the corporate tax rate is lower than the personal rate. Second, by having the company retain some earnings instead of paying them out as wages, she has avoided paying employment or personal income tax on that amount. And third, Tanisha avoids paying employment taxes on a significant chunk of her profits by taking it as a dividend rather than salary.

Keep in mind that the example above is simplified almost to the point of being unrealistic. Importantly, it doesn’t take into account state income and employment taxes, which can have a big effect on a business’s bottom line. There are also important long-term tax consequences that can come into play, especially for businesses that will have substantial assets like expensive video equipment. When it comes to shut down the company, the tax consequences of liquidating the company’s assets can be significant.

There are two key points to this example. First, it shows that the choices you make about how your business is organized and run can have a big effect on your financial outcome. Second, it shows the value of running through a few tax scenarios using your anticipated revenue and expenses. Explore how state and federal tax rules treat your big expenses, like health care premiums and equipment. Would you benefit from keeping cash in your business, where it will be taxed at lower rates than your salary? Do you anticipate earning enough to take advantage of a mixed strategy of salary and dividends? Consider using one of the many online tax calculator tools to help you in your research. You may be pleasantly surprised by how much you can save by making certain choices.

The Mechanics of Tax Treatment Elections

As discussed in Chapter 4, corporations that operate with their default treatment as tax-regarded entities are called C corporations, or C corps. Corporations can elect to be treated as pass-through entities, by becoming S corporations, or S corps. LLCs are the opposite of corporations: by default, an LLC is a pass-through entity, but it can elect to be taxed as a C corporation.

Freelancers who form a legal entity and plan to use the default tax treatment, there are no special steps to take at the time the company is formed, other than obtaining a tax ID number for the business. But for those who plan to change the company’s default treatment, there are important steps that must be taken on time to avoid a lot of costly headaches.

Corporations that wish to be treated as S corporations file IRS Form 2553 Election by a Small Business Corporation, also known as a Subchapter S election.8 This form gets signed by each of the corporation’s shareholders. As of this writing, the form must be filed with the IRS no more than 2 months and 15 days after the beginning of the tax year when the election is to take effect. The IRS treats the 2-month period as ending on the day before the corresponding day of the first month. Keep in mind that the first tax year for a new corporation is always shorter than a full year, because the company will be formed after the January 1 holiday. For example, a corporation that is formed on May 23 measures its 2 months to July 22, then adds 15 days to arrive at a deadline of August 6.

A member of an LLC that wishes the IRS to treat the company as a corporation—that is, as a C corp—can file an IRS Form 8832 Entity Classification Election.9 The form needs to be filed with the IRS within 75 days of its effective date. New businesses probably will want the effective date to be their formation date.

Missing the deadline for a Subchapter S or Form 8832 election ordinarily means that the election won’t be effective until the next tax year. A company that files late ordinarily gets taxed according to its default rules for the year in which the late filing was made. The IRS allows companies that accidentally miss the deadline to argue that it should be treated as though the filing was made on time, by asserting that they missed the deadline for “reasonable cause” and have taken diligent steps to correct the mistake. The IRS doesn’t have an official explanation of what “reasonable cause” means, but authorities suggest that it is fairly forgiving of situations where the responsible person simply forgot to take care of the filing.10 Nonetheless, being at the mercy of a petition to the IRS is not a good place to be. Better to complete your election filing on time.

James and the Giant Mistake

James is an experienced freelance medical editor who works for several large pharmaceutical firms. For various reasons, he and his accountant decide that his best option is to form an S corporation for his editing business. The accountant handles the paperwork for forming the company, using standard forms. When the company is formed, the accountant forgets to file the company’s Subchapter S election.

Two years ago, James, relying on his accountant’s word, has filed his taxes with the assumption that the corporation’s election to be treated as an S corporation is effective. As his business changes, James decides that the corporation is no longer needed, so he files the paperwork to dissolve it, again using his accountant’s advice to complete the transaction.

After the company is dissolved, James gets a letter from the IRS notifying him that his corporation has failed to pay taxes and is now subject to penalties. James promptly finds a new accountant and also decides to hire a tax lawyer to help him navigate the mess. Fixing the problem will not only require paying penalties and professional fees, James will have to revive his dissolved corporation, revise his tax filings of the last 2 years, and submit a new Subchapter S election together with an explanation about his accountant’s negligence in hopes that he can still get the tax treatment he wanted for a company that he thought was already wound up.

___________

1 Internal Revenue Service. 2017. Apply for an Employer Identification Number (EIN) Online. www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/apply-for-an-employer-identification-number-ein-online.

2 For more information see the State of California Franchise Tax Board website, www.ftb.ca.gov.

3 For more information see the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts website, comptroller.texas.gov.

4 Internal Revenue Service. 2016. (Circular E), Employer’s Tax Guide, Publication 15, Cat. No. 10000W. pp. 23-24. Note that an additional Medicare tax of 0.9 percent is collected on wages in excess of $200,000 in a calendar year. Id.

5 Id. p. 23.

6 State of California Franchise Tax Board. 2016 California Tax Rates and Exemptions. 2017.www.ftb.ca.gov/forms/2016-California-Tax-Rates-and-Exemptions.shtml?WT.mc_id=Business_Popular_TaxRates#ctr.

7 The example uses 2017 single filer tax rates for personal income. Income taxes are calculated progressively. In 2017, the progressive tax brackets were 10 percent for the portion of income that is from $0 to $9,325, 15 percent for $9,326 to $37,950, and 25 percent for $37,951 to $91,900. Kyle Pomerleau. 2016. “2017 Tax Brackets.” https://taxfoundation.org/2017-tax-brackets/, (accessed August 1, 2017). In 2017 the corporate income tax rate was 15 percent on taxable income up to $50,000. See PwC. 2017. “United States Corporate – Taxes on corporate income.” http://taxsummaries.pwc.com/ID/United-States-Corporate-Taxes-on-corporate-income, (accessed August 1, 2017).

8 Internal Revenue Service. 2017. “Form 2553, Election by a Small Business Corporation.” www.irs.gov/uac/form-2553-election-by-a-small-business-corporation, (accessed August 1, 2017).

9 Internal Revenue Service. 2016. “Form 8832, Entity Classification Election.” www.irs.gov/uac/form-8832-entity-classification-election, (accessed August 1, 2017).

10 Internal Revenue Service. 2017. “Late Election Relief.” www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/late-election-relief, (accessed August 1, 2017).