CHAPTER 2

CHOOSING YOUR PORTFOLIO

As I entered the symphony office, I thought about all that I had learned so far, and while I felt overwhelmed, I believed that I had a structure that I could now follow. I scheduled a meeting with the director to go over the upcoming season and see what his ideas were.

Maestro Fernando's back was to me as I knocked on his open office door. He had a set of headphones on and was conducting the music spread before him on an oversized music stand.

He must have felt my presence because he turned around and switched off the turntable.

“Hey, Jerry,” said Fernando. “I'm sorry. I was going through the second movement of the Firebird Suite.”

“Oh, I love that piece,” I replied. “Are we playing it next season?”

“You didn't get a copy of next year's season? You should have said something,” Fernando replied as he rifled through one of over a dozen stacks of paper. If anyone needed some portfolio management, it was Fernando. I didn't feel I was in the position to suggest it. Not because I lacked a firm grasp on the concept; it was more that Maestro Fernando was not known for graciously taking advice.

“Here,” he said as he handed me a list of concerts scribbled on two sheets of notebook paper. I looked at all the pieces he wanted to add and began panicking a bit. There were a lot of big pieces that required a lot of players. There were sequences of numbers under each piece.

“What are those numbers?” I pointed to the page: Wagner, Prelude to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg; Ravel, La valse (Commissioned Piece); Stravinsky, The Firebird Suite (1919 version).

- 2+1, 2, 2, 2, 4, 3, 3, 1

- 12, 12, 12, 10, 8

- 1 timp, 1 tri, 1 cym

- Harp

“You've never seen that notation?” asked Fernando with a slightly annoyed tone. “Are you sure you're ready for this?”

Maestro Fernando wasn't on the committee to choose an orchestral manager, nor was he a decision‐maker; that was left to the board. I don't believe I was his first choice. We had always been friendly to Fernando, but because I had been on the Orchestra Committee, he and I had bumped heads on a couple of items, such as breaks during rehearsal. His view had been that we needed to continue playing, and they might let the musicians out a little early if they covered all the pieces, but that rarely happened. In fact, he was renowned for going overtime, which meant time and a half for every minute we went past the designated time.

“To be honest, I'm just learning; I'd appreciate any help you can provide me,” I answered.

“Well, I don't have time to teach you how to be an orchestra manager. Those numbers refer to the number of players we will need for each piece.”

That would be helpful when creating a budget for the year. It would be hard to gauge what special instruments like a saxophone would cost, as they were not contracted players, but at least I could build a range into the budget that I would submit to the board of directors.

I looked over the entire season. There were six regular concerts, four chamber concerts with a new string quartet in residence, and a series of in‐school concerts. This year we were going to do concerts with the local choral society. I always enjoyed these concerts; the choir was close to two hundred strong, and the concerts were the highlights of the Christmas and Easter seasons.

Two of the concerts had empty spots in their lineup. “What pieces are we playing here and here?” I asked.

“I thought Sam would have told you already,” said Fernando. “We have commissioned two new pieces by Kimberly Goodwich for our Masterwork concerts. These pieces are to honor our centennial. They are not completed yet, and so they don't have titles.”

Sam Colbern was the symphony director. He dealt with all the business aspects of the symphony. I had not had a chance to talk to Sam before meeting Fernando, and now I regretted that a bit. Sam was the one who had made the decision to hire me for the position.

“Do we know the instrumentation for those pieces?” I asked.

“Not yet, but I will make sure you have the numbers in plenty of time before rehearsals.”

That wasn't comforting for two reasons. The first was the most immediate; I had to create a budget to submit to Sam and the board. I didn't want to pad the numbers, so I would have to ask the board to be aware that there could be a higher cost if we needed many more instruments.

The second issue was that if there were a need for a number of extra musicians, it might be difficult to find them. I was usually booked for gigs six months to a year in advance. Finding someone last minute could be difficult and expensive because I wouldn't have much negotiating room if we were desperate.

“I'm going to have to set up auditions this summer,” I said. “I wanted to make a few changes.”

Again, I saw a small wince on the maestro's face. “And those are?”

“Well, I want to make them blind auditions. You know, I would put up a screen, and they would be given a number. There have been complaints in the past that auditions were not fair because the committee could see the musicians.”

“Who said that?” replied the maestro. “Are people saying I'm not impartial?”

I knew this was going to be a sore spot with Fernando, so I was prepared. “All of the major symphonies – New York, Chicago, Boston – have blind auditions. I just want our symphony to be up to date with the trends of bigger symphonies.”

I knew this would appeal to Fernando's ego. He felt our symphony, which was a midsized orchestra, could play as well as any other major symphony. I actually applauded that sentiment because it pushed us to play better.

“Okay, but I still want to have last say on who the contract musicians are,” replied Fernando. “I am the music director, and that is my job.”

“Of course,” I said. “I will put together a process for that as quickly as possible.”

“What else do you want to change?”

“Well, I'd like us to audition for sub musicians. I also would like to be able to pay them a little more.”

“I don't mind auditioning sub musicians, and maybe some of the people who don't get a contract position could be considered for a sub position. But let me be clear – I don't deal with money at all. I don't want to know about it or talk about it. That is between you and Sam to figure out.”

I made a mental note not to bring it up again with Fernando, but it could tie my hands a bit. I saw a number of specialty instruments and larger ensembles on the season schedule, and they might be hard to fill if I didn't have the budget for them. It was something I would have to talk to Sam about. The maestro wouldn't care what it cost as long as a position was filled with the highest‐caliber musician possible. It fell to me to figure out how that would happen.

“I hate to cut our meeting short, but I need to get to lunch with some of the donors. I don't really like these types of events, but Sam often reminds me that without donors, subscribers, and endowments, I would not have a job.”

“That was pretty much it for now,” I said, even though there were a few more items I had hoped to discuss. “Can we meet again soon to talk through some other items?”

“Sure, but be aware. In three weeks, after the meeting with the board, I will be gone guest conducting in the Hamptons for about five weeks. You can send me emails, I suppose. I'll be back in town about two weeks before we begin our first rehearsal. I guess you'll need to schedule those auditions in the next couple of weeks before I leave town.”

I panicked; my heart beat hard and I broke out in a sweat. I had wanted to do auditions in July, but now I would have to schedule them sometime in the next couple of weeks. I needed to contact Dr. Richardson about how best to organize this audition. But first, Sam and I needed to speak.

MEETING WITH SAM

I waited at the table for Sam to arrive. I already had a cold pint of ale waiting for him. Even though it was just past noon, I knew Sam would appreciate it.

Sam McPhee had become the executive director a couple of years ago. He came from a business background of working at places like Nike and Pro‐Star. His background wasn't in music, and while he seemed to have an appreciation for classical music, he didn't really understand musicians and their special temperaments.

This often put him at odds with Fernando, one arguing artistic integrity and the other dollars and cents. Sam and I hit it off at an after‐concert party, sharing similar tastes in food and drink, and we both liked playing golf. He would often invite me for a round at the local country club, followed up with lunch, usually his treat. Today I was paying the bill because I needed his attention and advice.

Sam was my direct report, and so I needed to make him happy with my work if I expected to continue in my position. My wife was not happy with my choice to take the position in the first place; she felt I was in over my head and that it was going to stress me out. She wasn't totally wrong, but I wanted to give it my best effort before throwing in the towel.

One of the things I liked about Sam was his bright smile and high‐spirited nature. He loved telling jokes and was always positive about things no matter what was happening. I wished I had his eternal optimism. I hoped some of it would rub off on me today.

Sam walked in, with his bald head and his ruddy complexion. He had no hair now, but I could imagine locks of red hair in his youth. He had grown up in Scotland, and even though he had lived in the United States longer than he had in Scotland, he still had a significant accent.

He sat down in the booth and shook my hand warmly.

“Good to see you, Jerry.” As he sat down, he looked at the frosting pint in front of him. “Is this for me?”

“It is!”

“You know me so well.” Sam took a few sips and wiped the foam from his mustache.

The waitress came by and we gave her our order. By the time she walked away, Sam's glass was almost empty.

“Do you want another one?”

“Of course I do, but I want to be able to drive back to the office, so I need to pace myself.”

We chuckled.

“How do you like your job so far?”

“Well, I'm trying to figure it all out,” I admitted. “I appreciate the opportunity, and I'm trying my best to get organized. I'm unclear what you need of me and timelines and such.”

“Oh, no worries,” said Sam with his eternal optimism. “You'll figure it out.”

“Yeah … I wish there was a guidebook or something,” I chuckled. “My biggest challenge is the upcoming board meeting. They'll be expecting a report from me about the season's budget, and I won't have exact numbers.”

“Well, how close will you be?”

“There are some pieces that haven't even been written yet, so I won't know the personnel needs of them. I don't have any budgets for the quartet in residence. Also, I don't have any budget for the in‐school concerts because I don't have a list of how many there will be or what the personnel requirements will be.”

“All great concerns. We can fill in the gaps with last year's budget for now. What numbers do we know?”

There was that eternal optimism. I handed him the sheet with the concerts and the personnel numbers. I was pretty sure he cursed under his breath, and his face turned a cherry color.

“This is absolutely ridiculous. He knows we were a little short on donations and ticket sales last year,” said Sam in an angry tone. “If we submit these numbers, there is a good chance that the board may vote for a pay cut. Maybe I will have that second beer.”

He cursed under his breath, but I couldn't quite catch the words.

“A pay cut?” I asked. “No! We are barely paid what we're worth now, and I was going to ask for a small raise for the orchestra.”

“Well, then I would say we will have to figure out ways to cut our costs,” Sam said. “Even if they don't feel the cut this year, next year they will if we're too far over budget.”

This was becoming worse by the moment. I was glad that I had a meeting with Dr. Richardson tomorrow. I needed to get organized and get my head wrapped around program management, or I'd be sunk.

We finished our lunch, and I grabbed the ticket before he could.

“Come on, you're my employee now,” said Sam.

“I know, but I need your guidance on this, so I don't mind paying.”

“Don't worry, Jerry, you got this. I know better than anyone that Fernando can be difficult to deal with, especially when it comes to money, but I have your back. Make sure I have to budget in enough time, and I can fill in the gaps. You'll get the hang of this, I promise.”

As I walked to my car, I hoped Sam was right. Perhaps Laura was right; maybe I did take on too much. Even though Sam seemed confident in my skills, he had not provided much about how I should prioritize my time and what projects needed to happen first.

Tomorrow was a new day, and I hoped Dr. Richardson could help me, or at least point me in the right direction.

MEETING WITH MENTOR

“Thank you so much for meeting with me, Dr. Richardson,” I said. “This is all a little overwhelming.”

“No worries,” Richardson said. “My wife and I appreciate the tickets for next season, and I never mind someone else paying for my gourmet coffee addiction.”

I told Richardson about my meetings with Sam and Fernando. He listened, nodded his head, and scribbled a couple of notes.

When I was done, he took a big sip of coffee.

“You're right; there is a lot of material to consider,” said Richardson. “Just take a deep breath and relax. There are a number of things that could sidetrack you from your main goal, which sounds like the upcoming budget meeting. Do you remember when I talked about portfolios in my class?”

I grinned and shrugged. “To be honest, I never imagined I'd be in the position that I am in now. Can you give me a little refresher?”

Richardson chuckled. “No problem.” He took a couple more sips of his coffee while he gathered his thoughts. He opened up a folder he had brought and handed me some papers.

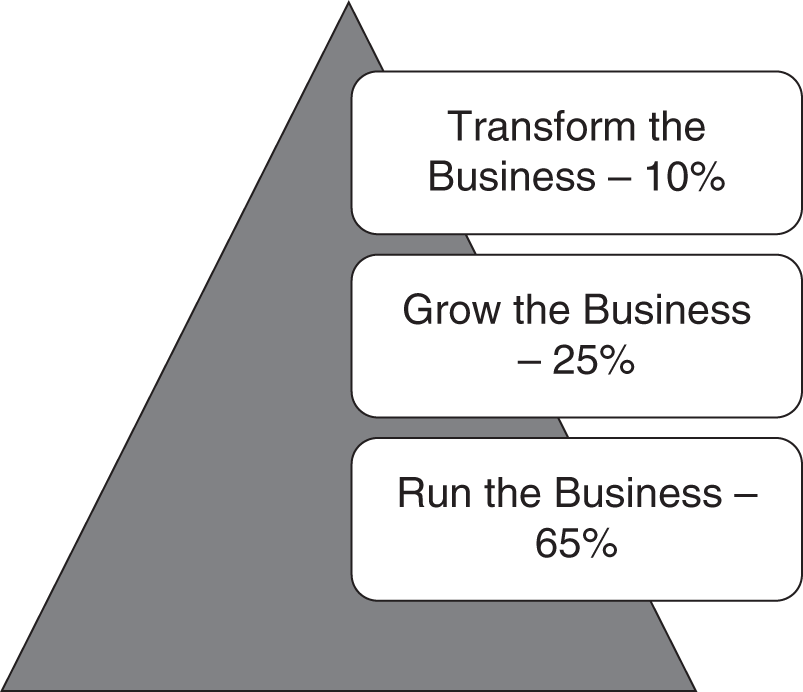

“One of the key ways to organize a portfolio of projects is to organize them by what's known as a portfolio mix or categorization. This portfolio mix contains three buckets. One is transforming the business, another growing the business, and finally running the business. So think about your orchestra. You want to break the projects in the portfolio into three categories – transforming the symphony, growing the symphony, and running the symphony. You following me so far?”

“Yeah, some of it is coming back to me.”

“The transforming part of the symphony project can be projects like televising the symphony orchestra on major television, or having a very famous conductor or composer write a premiere piece just for that orchestra.”

“Most of the things are happening this year,” I mused.

“To grow the symphony,” Richardson continued, “you could find ways to cut costs by streamlining a process or reducing paperwork, making it faster for symphony musicians to get paid. You may even decide to obtain two additional endowments that will add funds to the orchestra's budget.”

“I do want to make paying symphony members easier by switching us over to direct deposit.”

“Finally, running the orchestra portion, you could develop projects related to keeping the symphony running smoothly by having a database of symphony musicians and alternates who can quickly be called upon.”

“I want to streamline getting musicians their music sooner and prevent parts from being lost. My plan is to work with the symphony librarian, Reggie, to digitize the music. Would that fit in the running portion?”

“Yes, absolutely. You're getting it.”

“But how do I prioritize these things? I mean, I could organize them, but what do I do first?”

Richardson pointed at a paper in front of me. (See Figure 2.1.)

Figure 2.1 Categorizing investment types.

“Figure out what pieces need to be in place or created to execute. Once you have a list of projects that are categorized based on the transform, grow, and run categorization, you will need to determine and evaluate how you can execute those projects. First, you want to evaluate what projects are currently under way, and then you'll want to weed out any projects that are not in line with the overall strategy for the orchestra this season.”

I was a bit nervous. I didn't want to take up too much of Dr. Richardson's time, but at the same time, I was feeling lost.

“I feel like I'm monopolizing your time,” I said. “Do you want me to pay you anything?”

“Yes, you can buy me another cup of coffee,” Richardson said. “But in the meantime, I want you to consider some questions as you begin to organize your project portfolio. One is how many projects can the symphony absorb at any given time?”

“I'm not sure,” I said. “Since this is my first year doing it.”

“Perhaps that's a good question for Sam then.”

As Richardson talked, I scribbled down notes on a small steno notebook I had brought.

“Here are some other questions to add to that. Does the symphony have the capacity to deliver the selected portfolio of projects that are being considered? Does the project portfolio need to be synchronized to adjust to the demands and provide some buffer so that the orchestra is not getting overwhelmed with too much activity?”

I wrote down the questions as quickly as I could, barely having time to absorb their meaning.

“Once you've evaluated each project, you can create a simple valuation process where you either weigh the projects or you use a subjective weighing within each category; we also need to understand the urgency of each request as well as the risk of completing the project. You need to determine how difficult the project will be to implement and what is the cost of implementing the project.”

“This seems like a lot,” I said. “Will I have to figure all of this out before the budget?”

“Much of it, yes, but there are tools that can be used to help streamline this process. To begin with, you are creating your portfolio for your own use. So you can keep it simple and use a spreadsheet. I also have a friend London who has a tool called Transparent Choice. It's a very easy tool to use for managing a portfolio of projects and helps you make decisions about which ones to execute first. You can have other members of the orchestra committee weigh in on which projects they think should happen first. This helps with buy‐in and execution because you are establishing a team and not taking all the tasks on for yourself.”

“That would be terrific. What was the name of that again?” I asked.

“Don't worry; I can provide you a link, and we can discuss that next time when you have a look at it.”

“I'll go grab you that coffee,” I said. While the barista steamed the milk and poured the espresso into the cup, I received a text from Dr. Richardson.

I sat down with our fresh lattes, and Dr. Richardson had another little stack of papers in front of him.

“I know you're really nervous about submitting your budget request to the board. There are a couple of tools you can use that we talked about in class that you probably don't remember.”

My cheeks burned a little, and I tried not to make eye contact. He pushed the papers over to me.

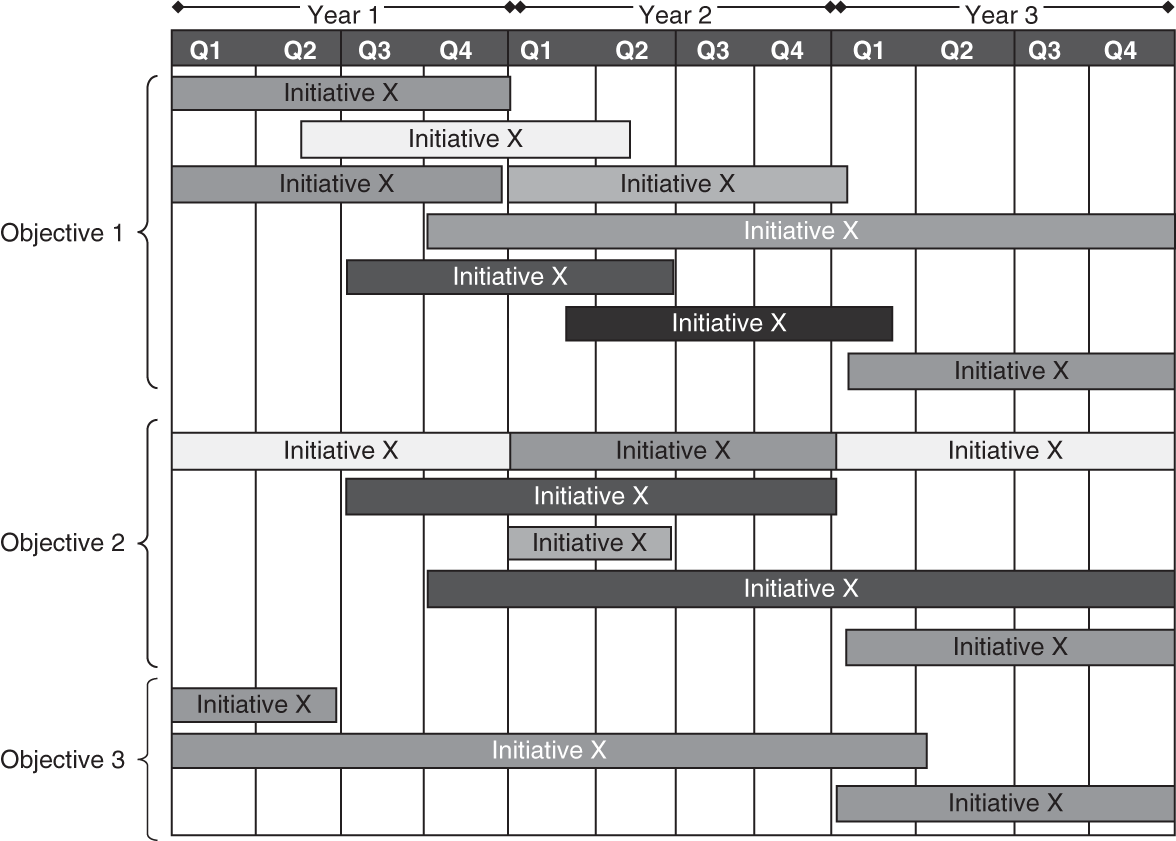

“One of the tools is the portfolio roadmap, and the other one is a cost‐benefit analysis.” (See Figures 2.2 and 2.3.)

I looked at the large chart on the first page.

“For the portfolio, the roadmap is really an investment roadmap that provides short‐, medium‐, and long‐term views of how the projects will be laid out and which projects will get done first. The roadmap facilitates dialogue and helps build agreement with an organization regarding the funding required for the projects to be completed and the resources required or resource allocation plan as it aligns with the overall goals and objective for the symphony.”

I looked over the map of objectives and initiatives.

Figure 2.2 Portfolio roadmap.

Figure 2.3 Cost‐benefit analysis.

“So I don't have to implement everything the first year. That's why you asked me about how many projects the symphony can handle at one time.”

“Precisely. You can create a similar portfolio roadmap and submit it to your board.”

“Wow, I'll actually look like I know what I'm doing,” I laughed.

“You'll be a pro by the time the season is over.” Richardson put another paper in front of me.

“This is the cost‐benefit analysis document or spreadsheet you can use for each project. It contains information like the total investment and how much it will cost. It can be used as a guesstimate of the total benefit that the organization can expect because of doing this project. It addresses any assumptions around the benefits as well as whether there are hard benefits like real dollars, soft benefits like intangible items, or strategic benefits. This will show the orchestra in a new light now that there are things like discount rates, payback periods, net present value, and discount ROI.”

Richardson must have seen my eyes glaze over a bit.

“At this point, I don't think we need to go into those types of details for this list of projects,” he continued. “But those are some things to consider. Do you have access to the online course I was telling you about?”

“Yeah, but I think I misplaced the link,” I admitted.

Dr. Richardson quickly typed on his phone, and mine dinged, letting me know I had just received a text.

“I highly recommend you take time and look at that course. It teaches a lot of the same things I teach in my class, but you can do the lessons from the comfort of your home or office. Look it over, and it will walk you through and give you all the details around how to leverage all the components of a business cost‐benefit analysis. It will show how each project should have a benefit‐cost analysis along with the roadmap. This should give you what you need to present to the board regarding obtaining budget approval. I hope this helps.”

“You have no idea,” I replied. “This is exactly what I need. I promise I will be a better student than I was in your class.”

“Jerry, you weren't a bad student. A distracted one, and I understand. Your focus was on music. I am very impressed you decided to expand your horizons a bit, and the symphony is lucky to have you.”

“One last thing,” said Dr. Richardson as he pushed a stack of stapled papers. “This is a great Harvard case study that will give you an even deeper understanding of portfolio management. I would suggest getting an account and downloading some of their other studies. They are excellent and much more eloquent than I am. I'll send you the link.”

HARVARD CASE STUDY

MDCM, Inc. (B): Strategic IT Portfolio Management, https://hbr.org/product/mdcm-inc-b-strategic-it-portfolio-management/KEL172?sku=KEL172-PDF-ENG

“Again, Dr. Richardson, I can't thank you enough.”

“You keep buying me coffee, and you can have my ear for whatever you need. I can point you to what you need to do, but you have to put in the work.”

As I drove home, I thought about all of the things Dr. Richardson had shared with me. As I got closer to home, my stomach twisted a little. Laura was still on my case about the new position. Maybe if I shared with her the progress I was making, she would change her mind. That was a big maybe.

IT'S ALL ABOUT THE BASS

“Did you get my text?” asked Laura as I barely got in the door.

“Yes, but I haven't had time to get to all those stores,” I replied.

“What have you been doing all day?” Laura asked. “Your bass is over there, so I know you didn't have a rehearsal.”

I looked at the floor. I was not looking forward to this conversation.

“I had to go to the symphony office, and then I met with Dr. Richardson.”

“You what? You didn't take that job after you promised to turn it down?”

“I didn't promise anything,” I replied. “You asked if I could turn it down. But I decided to give it a shot. Look, if I can't make it work, I'll quit.”

“Then you need to quit because it's not working out,” snapped Laura. “I need you to be able to run errands and do things with the kids.”

I didn't want to remind her that she wasn't working, but I thought better of it.

“Listen, I can go out later and get those things. I wanted to be here when Corey got home.”

“Never mind,” she said as she grabbed the keys from my hand. “I'll handle it. I don't know why you insist on taking this job. You don't have any experience with it, and it doesn't pay enough for you to be away from home. I really hope for all of our sakes that you'll reconsider.”

Linda came out of her room and said, “Mom, why are you doing this to Dad? I'm proud he is doing this new position. I think it's cool.”

“You'll think it's really cool the next time you want to go to Betty's house, and your father is too busy to take you.”

Laura didn't wait for a reply; she walked out of the house.

Linda gave me a big squeeze. “I'm sorry, Dad; I think Mom is being really unfair.”

“Oh honey, don't worry about it. Everything is going to be just fine.”

At that moment, the door burst open, and Corey came running into the house.

“Hey, Dad,” he said as he dropped his backpack on the counter.

“Uh, the door, Corey,” I said.

The doctors described Corey as having ADHD. I had to remind him constantly about closing doors.

“Oh yeah,” he said without skipping a beat and ran to close the door.

“Hey, buddy, I have some good news I wanted to share with you.”

“What?” Corey's face brightened.

“I heard from one of the other players today. They have a student bass that I can buy. I'll be able to pick it up next week.”

“Really, Dad? Are you serious?”

“I am, but remember our deal. You need to practice every day. I'll invest in the instrument; you need to invest the time.”

“I will … I promise.”

I hadn't exactly cleared the bass thing with Laura. She didn't want the kids to follow in my footsteps as a musician. She felt they were destined to have careers in medicine or even technology. She didn't want them to struggle as I had as a professional musician. I disagreed. I loved my career, and just because I played in the orchestra didn't mean I couldn't also be good in business. I was determined to make my new job work and learn as much as I could from Dr. Richardson.

Dr. Richardson's Tips

- One of the key ways to organize a portfolio of projects is to organize them by what's known as a portfolio mix or categorization. This portfolio mix contains three buckets. One is transforming the business, another growing the business, and finally running the business. So think about your orchestra. You want to break the projects in the portfolio into three categories: transforming the symphony, growing the symphony, and running the symphony.

- For the portfolio, the roadmap is really an investment roadmap that provides short‐, medium‐ and long‐term views of how the projects will be laid out and which projects will get done first.