Strategy Quality and Strategy Success

This chapter explains why and how a strategy can be quality managed to deliver successful results.

The book does not wipe out the possibility to pursue a tacit strategy, i.e. a strategy living inside somebody’s head and not documented anywhere; on the contrary, it points out that anyone with a little luck can have a lot of success simply by doing what they believe is right. The problem with a strategy based on pure luck is that we cannot learn from it, there is no way we can repeat the process that leads to the high quality strategy.

In order to be able to quality manage a strategy; such a strategy must be established and implemented based on sound and visible processes that can be documented, evaluated, improved, and (re-)used.

The processes described in the book with their organization, standards, and results cover the full strategy lifecycle from establishment to successful implementation or abolition.

The initial knowledge in my companies was based on more than 10 years of practice in project and program management governing information system development and implementation in support of strategic business change and development initiatives.

We have never regarded our methods, techniques, and standards as proprietary or confidential. There are a few reasons for this attitude:

• Once an idea is born, it is the foundation for even better ideas—if you share it.

• We want to share our knowledge with our clients and other partners.

• We do not regard our methods as unique or the best, but we want them to be world class and at least as good as the best.

• We learn as much from clients and partners as they learn from us.

• We are here to have fun, not to live in fear that someone will steal our ideas.

In order to be able to transfer our knowledge, we had to document our methods and techniques in such a way that we could teach it.

All the employees in my companies were encouraged to teach even if they had not tried it before. After all, we were introducing new ways to improve business and manage change and quality in corporations, so without the capability to teach we were not able to transfer our knowledge fast enough to the clients and to new employees.

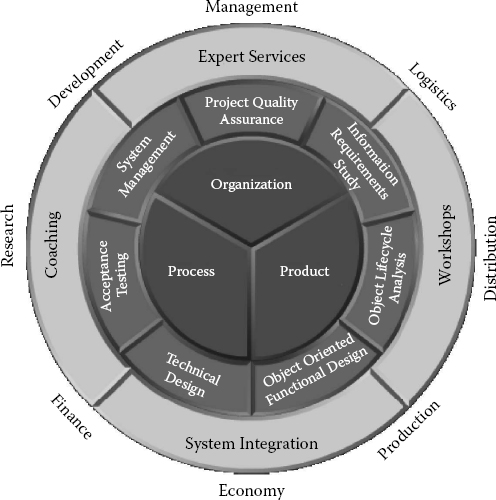

Based on this need for knowledge transfer and sharing, our methods of agile quality management and our agile principles in general were developed under the name of the Lyngso Model (Figure 1.1), which is a comprehensive collection of methods and techniques for the conduction of strategic initiatives.

FIGURE 1.1

Lyngso method and technique framework.

All our clients had a copy of the manual that explains how we use the methods, techniques, and standards free of charge. In this way, they could verify what the ideas were behind the work performed by our coaches and facilitators. It was our way to present our quality management system to the clients.

The development of our methods and techniques has never stopped.

Over time, many strategy management standards have been developed, for example, the IS0 9000 public family of standards, the continuous quality improvement with Six Sigma from Motorola, the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) concerned with organizational method maturity from Carnegie Mellon’s Software Engineering Institute (SEI), COBIT, and ITIL.

We continually verify that our agile methods comply with these standards. This is not as difficult as one might think because of the following:

• Our standards are based on specific methods and techniques, which is basically never the case with the public standards that make reference to best practice, but do not show what this best practice is.

• The public standards advise you to establish methods and techniques for the type of work that your organization does, but not how to do this.

• We deliver services based on our specific standards that are continuously improved from working experience.

• We present why and how we have done something. The public standards present what to do and to some extent why, but only in rare cases how.

Enterprise Information Systems, Business Behavior, and Business Organization are continuously kept synchronized and adapted to the environmental conditions and opportunities in order for the enterprise to obtain the maximum benefits from technology, market opportunities, knowledge, and experience.

If this synchronization is not done, your enterprise will encounter serious problems such as the following:

• Competitive industry will squeeze you out of the market by better usage of technology to offer better products with better performance at the same or lower price.

• Your clients find other more attractive ways to obtain the benefits that you used to offer by replacing your products and services with new ones.

The industry examples are legion. Nokia has lost market share to Apple and Samsung, supermarkets are replaced with shopping centers, European production of basic products such as cloth has been moved to China and India, Novo Nordic has obtained a dominating position on the insulin market based on innovative products, etc.

The needed synchronization is a never-ending process of change. The change is managed in order to ensure that the most competent resources get involved at the right time to produce the solutions that are the best fit to the market conditions and the client needs and expectations, when these solutions are ready for the market.

The synchronization of enterprise Information Systems, Business Behavior, and Business Organization takes place within strategic initiatives (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2

Synchronized strategy framework.

Strategic initiatives most often comprise planning, development, and implementation of new Information Systems and adaptation to already implemented ones in support of:

• Establishment of new business

• Changes to organization structure

• Implementation of new technology

• Implementation of improved production methods

• Implementation of improved logistics

The information system makes it possible to obtain the required result of the strategic initiative, but the information system is worth nothing if it does not correspond to business processes that deliver real customer benefits.

In the case of the pharmaceutical factory implementation, the first information systems delivered had left quite a few industrial processes under human control, such as, for example, physical and geographical movement of important production elements. When the quality manager had inspected a great number of quality problems, it became clear that 90% of all problems originated in the manual processes. There were no room for such problems in the long run, so today all logistic movements are handled in an integrated process and the error percentage has been reduced to close to zero.

1.2.1 The Importance of Synchronization

Let me tell you about a failed strategic initiative of Information System improvement that ended up in a pure catastrophe because the synchronization of business behavior, organization, and information systems was not done.

A major distributor of big and small electrical household equipment decided to swap its Information System because the current system was getting very expensive to maintain and was very slow.

The IT installation comprised an old-fashioned mainframe with attached PC workstations that the distributor wanted to swap with state-of-the-art Microsoft-based servers with Windows workstations.

The employees and connected clients and partners were used to and very competent in the usage of their current Information System functionality that supported the business processes well nationwide.

The business owner had a friend who was developing and selling a contemporary COTS (Commodity Off The Shelf) system addressing the needs of major equipment distributors. On paper, this new system was based on contemporary IT technology fitting the needs of the major distributor.

As the new COTS application was built for equipment distribution, it was deemed not necessary to establish a requirements specification that would have had to be done by very expensive business consultants.

Therefore, the system was bought from the friend who also became responsible for swapping the business Information System and for training the future users.

The swap consisted of data transfer from the old system to the new one, which was supposed to be much better than the old one—although “better” was defined only as “faster response time and a more user-friendly web-based user interface.”

An Accept-Test was established after the data had been transferred to the new system. This Accept-Test was a mere demonstration of the new system for the future users thereof. All questions of a critical nature were wiped away with answers such as “This will be available once in operation and once you have been trained in using the new system.” The questions and answers were not documented, and the business owner accepted the new system to go into production immediately.

The start of usage happened as a big bang once all data had been transferred from the old system—of course, only the data relevant for the new system—and the system had proved available to all future users technically speaking.

The future users were:

• Shop owners placing orders and receiving equipment to their local warehouse and in response to client orders.

• Central and distributed personnel managing stock, purchase, logistics, and finance.

Once the users opened their wonderful new system, the problems began:

• The products were there, but only once.

• Stock locations were simple sub-structures to the central warehouse without specific pricing, purchasing, and delivery conditions.

This was completely different from the old system, which had been established as a real Information System in support of their specific business strengths and needs.

The new “solution” was based on business conditions dreamed up by the COTS software vendor.

The COTS software vendor offered very expensive adaptations with delivery lead times that were unacceptable. Furthermore, the COTS vendor would not maintain specific adaptations to the COTS software.

Unbelievably, this is a true 2012 story, and the poor employees and shop owners are still struggling with manual adaptations allowing them to do their business only based on homemade spreadsheets even today in 2013.

In 1986, I established my first company, Lyngso Information Industry, with the objective of delivering strategically aligned Information Systems to our clients.

The background for the “Information Industry” part of the name was that we could promise delivery of fully accepted Information System solutions based on safe estimates emanating from standard dialogues with all pertinent stakeholders in the context of fully standardized processes for business analysis and for object-oriented solution design.

These dialogues take place in scenarios that ensure motivation and best possible contribution from all involved stakeholders to such a degree that these stakeholders want to take ownership of the result—collectively and without conflicts.

It is a basic agile principle of our methodology that we strive to make the client take ownership of whatever is delivered.

We will contribute to the client solution by delivering whatever tools, techniques, and solution components we happen to have the competence to deliver. The final solution inclusive of the knowledge transferred or shared belongs to the client.

Our methods and techniques cater to Strategic Initiative establishment and governance that align Information System development, implementation, support, and governance in any industry with corporate strategy.

The methods and techniques have been used successfully in industries such as:

• Oil and gas production

• Logistics

• District heating production and distribution

• Electricity distribution

• Pharmaceutical production

• Public sector

• Healthcare

• Finance (bank and insurance)

Wherever we have contributed to strategically aligned corporate information system solutions we have left our documented standards used for this work with the clients for them to use it without any restrictions.

It is a real pleasure to come back more than 10 years later to find that the standards are still in use in the organization.

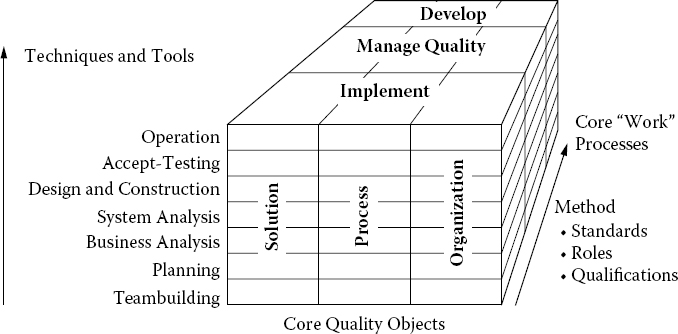

Our first clients declared that it was the first time they saw a true strategic angle to Information Technology and Information System solution development and implementation. Today, more than 25 years later, we are not first anymore, and probably not even unique, but we do have some stories to tell (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3

The strategy management framework.

All method components are explained with respect to the core quality objects:

• Organizational requirements

• Process requirements

• Solution requirements

The Core Work processes of Implementation, Development, and Quality Management are all established in support of agile behavior, where the concurrent involvement of competent resources ensures fast adaptation to unexpected and risk-managed situations and events.

The standard processes and documentation used in the core processes contribute to efficient progress tracking and quality management from the start of a strategic initiative to the delivery of the expected result.

The concrete techniques and tools that are used in all development, implementation, and quality management processes ensure the full traceability of all results from idea to solutions in operation. Traceability is especially important while working agile, where results are adapted to changes in stakeholder demand.

The methods have been developed to be used during the different phases of strategic initiatives, where the strategic initiative can be an information system engineering project; but the methods and techniques have also been used for pure business process engineering such as the establishment of a new factory.

1.3.1 Agile Strategy Quality Management

The techniques and standards for team building and object-oriented business analysis and solution design have been developed to solve the broader and more complex tasks of strategic Information System planning, development, and implementation governed by Agile Strategy Quality Management.

The Agile Quality Management standards used in strategic initiatives comprise:

• Identification and activation of stakeholders to be involved

• Communication

• Team building

• Decision making

• Documentation

The Quality Assurance and the Quality Control methods of Agile Strategy Quality Management ensure that the key-stakeholders are satisfied with the delivered solutions.

The standards are established to be complementary to and sometimes replace components in industry specific or national method standards for delivery of solutions with the quite ambitious objective that:

The standards can be understood concurrently by the most hard-core technicians, by the top-level visionary leaders, and by all other strategic initiative stakeholders.

Each strategic initiative stakeholder expects different types of benefits from the initiative, and each one reviews and tests the solution to be delivered for his or her own reasons, that is, the proper WHY that you need to understand.

The agile ongoing quality assurance of the solution, the organization, and the processes of a strategic initiative has contributed to the success of the methods used.

A fundamental capability of the methods is that they allow rapid solution development in order to be able to capture the solution benefits while they are relevant. This capability is ensured by early visualization of the complete solution structure and by ensuring that solution elements can be delivered and made productive early during a strategic initiative; that is:

• Complex solutions are broken down into fully functional business solution components without losing the overview of the total solution.

• Early delivery of solution components allows experience to be gathered early for improved estimation, planning, and optimal adaptation to risk events and conditions.

• Early usage of solution components allows the users to gain benefits and to avoid major problems.

In the context of methodology, it should be remembered that no method is perfect and that a great number of different industry, enterprise, or national specific standards exist. While establishing our specific methods we have tried to provide the following advantages compared with such other methods and standards:

• People and communication come before processes, and processes come before documentation standards for the very simple reason that no process can run without resources, and even well-chosen people cannot perform well without good processes to govern their work.

• Documentation standards are simple and cover only the necessary elements. The documentation standards can be seen as content suggestion or as checklists. The methods promoting documentation standards differentiated between complex and simple projects are doomed to fail because they never fit all projects.

• By providing only basic standards and norms, you give the teams the ability to expand to standards of their own that are required for the production of best quality or at least feasible results on their specific tasks. Again, the freedom to act is in focus.

• Your challenge as a leader, manager, or coach is to find the best people and build the best teams and to provide them with standards that work without constraining their ability to perform and adapt the standards to their needs.

• The methods have one basic requirement to all standard documents, which is that they must answer all WHY questions when used, for example:

• Why has the team been established the way it is?

• Why is this objective important for the enterprise?

• Why is this activity conducted the way it is?

• Why does this solution component function the way it does?

• Why is this test done?

• Why is this suggested improvement an improvement?

1.3.2 Quality Management Objects

Quality management comprises three process management classes with explicitly defined organization requirements, procedures, and result standards:

• Quality assurance ensures that a solution will satisfy the stakeholder needs and requirements. This is handled by establishing agreed standards for all resources, procedures, and solution elements to be involved or delivered.

• Quality control is the ongoing effort to maintain the integrity of a method to be able to achieve the required solution quality. We use communication, interview, and review techniques combined with advanced testing and verification procedures supported by standard quality management information systems to perform and document quality control.

• Quality improvement is the purposeful change of a method to improve the reliability of achieving a required solution. We have improved our standards and techniques periodically based on Lessons Learned.

For each quality management process class we use three quality objects as a foundation for evaluation of the performance of this process class:

• The Solution object defines the properties that are required from the solution to be delivered.

• The Process object defines the properties that are required for high performance delivery of the required solution.

• The Organization object defines the properties that are required for efficient communication, competence establishment, and decision making.

Our work with clients and partners has allowed a continuous improvement of our standards, techniques, and tools based on a vast base of gathered and documented experience and knowledge, some of which I want to share with you.

1.4 STRATEGY AND STRATEGIC INITIATIVES

Corporate leadership establishes the strategy of a corporation. The strategy tells you why the organization has been established the way it is:

• Organization structure and geographical locations

• Products

• Business operations

The strategy comprises:

• The corporate vision statement that “paints” a picture of how the corporation would like to be observed and how it observes itself in the future.

• The corporate mission that tells a story about how the corporation intends to contribute to the happiness of its stakeholders. This is the strategy quality objective.

• The confidential corporate objectives known by and sometimes contractually committed to by management tells you the direction followed by the corporation, for example:

• Internationalization

• Growth by acquisition

• Profitability (Return on Investment, Return on Equity)

• Sustainability

• Technological superiority

All organizations whether public or private have a strategy and perform business activity governed by this strategy more or less successfully.

Key performance indicators (KPI) and benchmarks measure the strategy quality and success.

Corporate management translates the strategy into detailed organizational constructions, business procedures, and strategic initiatives that can ensure and improve the strategy quality.

1.4.2 The Strategic Initiatives

The strategic initiatives establish the WHY, the WHAT, the WHEN, the HOW, and the WHO concerned with sustaining, changing, and improving business procedures and infrastructure in support of the corporate strategy.

Strategic Initiatives usually comprise information systems establishment or improvement in support of business operations. When my companies have been involved with corporate strategic initiatives, this has always been the case.

Strategic Initiatives are programs or projects.

The agile principles of our methods framework ensure that the strategy stakeholders are happy all the time.

Unfortunately, happiness is not the nature of Strategic Initiative stakeholders and especially not when corporate strategy and Information System implementation is concerned. Most often conflicts and disagreements between owners, operators, and unions about how to handle and manage the strategic initiative pave the way for mistrust and insecurity.

There is a long history of failed strategies, missed opportunities, and Information Systems that never were delivered, disasters that unfortunately enough support the normal stakeholder suspicion and mistrust.

On top of these bad experiences, the normal resistance to change and the classical differences in objectives between management and employees pave the way for unhappy stakeholders.

The agility is there to overcome the constraints of mistrust and suspicion among strategic initiative stakeholders. The core agility principle is:

Each process from the definition of the initial need for change to the final delivery of the agreed solution contributes to stakeholder trust, mutual respect, motivation, and willingness to take ownership of the solution components delivered.

This is the philosophy behind our processes, tools, and techniques. They involve the stakeholders in such a way that they feel that the results obtained belong to them. In this way, each process contributes to the motivation for the next one.

People creating software established the initial agile principles (“The Agile Manifest”) that you can look up on the web. This limits its formulation to very specific software development activity, which will not cover the needs of strategic initiatives and Information System development and implementation that involve many other elements than software and software development.

Our principles of Agile Strategy Management comprise the following:

The highest priority is to satisfy the stakeholders through early and continuous delivery of valuable solution components. We understand why the stakeholders need the solution and we know that the stakeholders like the solution.

Working solution components are the primary measures of progress.

Working solution components are delivered frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale. The delivery process is Simulated Accept-Testing where the developers of the solution present it to future users, who discuss it with the developers and test it out after thorough education and support.

Changing requirements are welcome, even late in development. The agile processes harness change to obtain improved stakeholder benefits.

Development, Implementation, and Quality Management stakeholders work closely together throughout the project. This is ensured by the environment of technology, communication facilities, space, and more. One of our basic requirements is a War Room where the involved parties assemble all that is needed to generate and evaluate the solutions required for decision making.

Projects are built around motivated individuals. It is ensured that they have the environment and support they need. As the individuals in the project teams have been selected based on their skill, experience, and competence, we can and will trust the teams to get their jobs done. This is the “no excuse for failure” principle. If the team claims that it needs something to get the job done, then it gets that something.

We do not establish or accept conflict during solution implementation; instead, we ask for a mutually agreed solution and progress without further discussion. Once the solution is in place, we are happy to evaluate if something could have been done differently and better.

The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is regular face-to-face conversation. One or more War Rooms cater to this behavior. We have even gone so far as to establish a contract-based situation where software development and solution implementation work was allowed to take place only in the War Room. No solution component could be brought in from the outside and nothing produced inside could leave the War Room before it had been fully Accept-Tested and signed off for IT and business operation. The War Room was a set of containers with approximately 500 m2 of spaces for work, education, and testing fully and securely supported by the central IT infrastructure.

Agile processes promote sustainable development. This principle ensures that processes can be repeated and evaluated for possible improvement.

Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility. Time is devoted to ensure that state-of-the-art technology is used, which again implies that the technology used is a solid foundation for the solutions that use it. Good design ensures normalized processes and data, which ensure integrity and valid integration in support of the agreed business needs. Once the business needs change it is easy to adapt good design, while bad design reveals itself under such conditions.

Only agreed necessary work is done. We list work not to be done explicitly only if doubts are raised. This is the Lean principle to avoid doing not required or not needed work.

The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams. The self-organizing does not ensure this situation, but the fact that teams have been put together in such a way that self-organizing is possible. We ensure that teams can:

• Make decisions

• Initiate work

• Do the work

• Evaluate the progress and the results

This makes simulated Accept-Testing great fun because the delivered solutions do work, although they may be improved in a meaningful (Lean) way.

At regular intervals, the teams evaluate how to become more effective, then tune and adjust their behavior accordingly. The evaluation comprises communication between teams and their environment of resource providers and other key-stakeholders.

The teams have fun:

• We celebrate visibly our successes, also the small ones.

• We do not hesitate to show appreciation of others.

• We are not jealous, but we like a good fight.

• An individual achievement is a team victory.

The fun part can comprise games that require professional knowledge and, quite often, professional development. The games provoke friendly competition in a team and between teams. The games are a great way to get to understand and respect the value of different personalities in a team. The teams do not need rules of the game imposed from outside the team, but they can easily adapt to such rules if needed.

A strategic initiative can be concerned with reaching many different objectives regarding different business situations.

This initial set of objectives provided by corporate leaders is an indication of what kind of business and stakeholders that must be involved in the establishment of the strategic initiative. In most cases in which we have been involved, these objectives were not precisely defined to establish the full scope of the strategic initiative on their own.

Only when we have asked key-stakeholders about their points of view on the objectives do we get a more precise idea about the scope that can comprise elements such as:

• Budget

• Competition

• Environment

• Technology

• Legal issues

Therefore, the first action in the establishment of a strategic initiative scope is to identify and to have open dialogues with potential key-stakeholders to be involved with the initiative, while you respect that you do not know what the real scope is—yet.

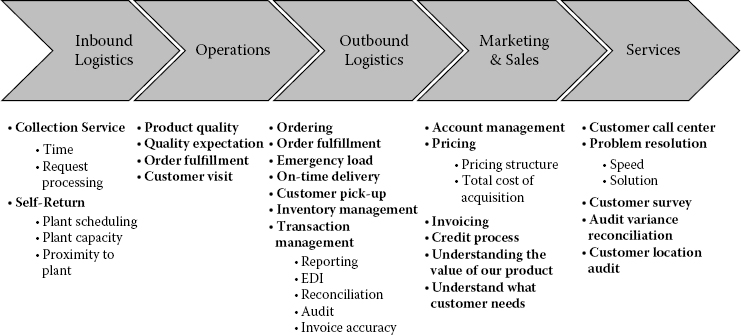

In order to identify all stakeholders to get involved or to be communicated with you need to look at the complete value chain (Figure 1.4).

A complete quality assured scope and stakeholder definition will follow later through a well-defined quality managed standard procedure such as Process Quality Assurance (PQA).

The result of the dialogues with the potential key-stakeholders is documented in an invitation to the group of identified key-stakeholders to participate in a PQA workshop.

In the workshop, the participating key-stakeholders define a more detailed scope of the strategic initiative:

• They present their individual visions of the initiative result.

• They present what they think the initiative mission is and how they can contribute to this mission.

• They define the initiative success factors and the agreed critical success factors.

• They define the set of activities required to fulfill the success factors.

FIGURE 1.4

Value chain example (from http://bettyfeng.us).

The PQA workshop establishes mutual respect among the participating stakeholders. The success factors replace the initial objective.

The full scope of the strategic initiative has only been defined when the complete plan for execution and delivery of detailed results has been signed off.

Imagine a toy manufacturer who wants to have a bigger share of the sale per outlet and at the same time have a higher contribution per outlet. The outlets are toyshops, supermarkets, catalogs, web-shops, etc. that make autonomous decisions about how to display and promote the toy manufacturer’s products.

What is the scope?

Right, there is no simple answer to this question!

Within this larger scope, you discover a broad range of benefits that can be obtained based on one or more appropriate strategic initiatives.

You also find threats emanating from, for example, differentiating prices between rich and poor countries or from misplacing stock locations giving too high transportation costs.

1.7 STAKEHOLDER IDENTIFICATION

In order to establish a strategically aligned solution, you deal with a multitude of stakeholders representing all the roles directly involved with development, implementation, quality management, usage, governance, etc. of the solution, as well as the not always visible stakeholders that potentially benefit or suffer from the strategic initiative and its solutions.

When establishing a strategic initiative you make a serious effort to get to know all the stakeholders that are concerned, that is, to have a dialogue with key persons and organizations that potentially could benefit or suffer from it. This is especially true for the less visible and less obvious stakeholders such as unions, politicians, government, legal bodies, and potential competitive businesses and partners.

In several cases, leaving out potential key-stakeholders has led to the complete failure of the strategic effort. Some real and recent examples of less efficient stakeholder management are addressed next.

Scandinavian mythology addresses the stakeholder identification problem explicitly with the Balder case, which most children learn about in Scandinavian schools and very well explains why stakeholder knowledge is crucial to strategy success.

The Vikings told the Nordic myths. Their stories are still told; now in books, poems, and films or as bedside stories. They represent some of the first documented storytelling and explains generation after generation the virtues and the dangers of the Aesir gods, how the world was established, and how the different natural events such as the sun and the moon were generated.

The two primary gods were Odin and Thor. Odin was the wise leader, the strategic thinker, while Thor was the strong manager who used his force to ensure the success of his sometimes fancy ideas.

Balder was the son of Odin and Frigg. He was the most handsome of the Aesir gods and on top of this very intelligent when it came to writing and reading runes. However, he did not like to fight. All gods and humans loved Balder. He was married to Nanna.

One day Balder told Nanna that he had dreamed of his own death. Nanna was very worried and went to Odin, who could see into the future, but Odin could not see anything. Odin got worried and saddled his eight-legged horse Sleipnir to ride to see Voelva, who was buried at the entrance to Hades (the world of death). She might know something. Odin saw a table prepared as if they were waiting for guests in Hades. Odin dug up Voelva and asked her whom they were expecting. She did not want to answer, but Odin pressed her to admit that they were expecting to receive Balder. “He will be killed by an arrow from his brother Hoder’s bow,” she said.

Odin came back home with the terrible news. Nanna and Frigg were very sad; but Frigg did not give up easily. To prevent that Balder died she went out into the world to ask all things to promise that they would not hurt Balder. She succeeded in doing this.

The Aesir gods were happy that Balder now was safe. They arranged for a big party where Balder would be used as shooting target. The party progressed well and stones, arrows, and even Thor’s hammer did not do any harm to Balder.

Loke was a terrible troublemaker god. He wanted to see if he could make more harm to Balder than the others. He disguised himself as an old woman and went to Frigg to ask her if there really were not anything that she had not asked. Frigg admitted that the small mistletoe had not been asked.

Loke cut an arrow out of the mistletoe and gave it to Hoder so that he could shoot with that arrow. Hoder refused because he was blind, but Loke offered to give him a hand. Loke placed the arrow on Hoder’s bow and helped him to direct the shot. The arrow went straight through Balder, who died on the spot.

Normally the place for dead gods was Valhalla, a paradise with eternal eating and drinking and friendly fighting; but only if the god had died fighting. As this was not the case with Balder he was doomed to go to Hel in Hades.

The god Hermod road to Hel in Hades, where he met Balder and his wife Nanna, who had died of grief on the funeral pyre of Balder. Hermod asked Hel if there was a chance to get Balder and Nanna back. Hel told him that if all living and dead creatures would cry over Balder they could get him back; but if only one creature refused she would keep them.

The Aesir gods were happy to hear this and arranged for everybody to cry. They succeeded until they passed by a cave with an old woman called Tok. She would not cry. The Aesir gods thought that this attitude was strange and went back to the cave, but Tok was gone. Odin analyzed the situation and declared that it must have been Loke disguised as an old woman. “Go and find him,” said Odin.

Loke had built a house on a high mountaintop, where he could see anyone who would attack him, but he did not believe that this would save him in the end. He therefore turned himself into a fish. This was counting without Thor, who finally caught Loke.

Loke was bound to a stone. A poisonous snake was hanged above him to let its poison drip on his head. Loke’s wife Sigyn collected the poison in a cup. Every time she emptied the cup, the poison hit the head of Loke and his body shook so hard of pain that the earth was quaking.

Balder and Nanna are still living with Hel in Hades.

How often have we left out a stakeholder from attention or involvement in a process because we thought that this potential stakeholder had no real importance to our project?

I was involved with a large program to automate a private bank giving all clients access to full web banking. Focus was on technology and functionality and all of this was successfully implemented and even Accept-Tested and approved before the disaster was discovered.

The bank clients only got involved to enter transactions after the fully integrated solution was technically functional and had been approved from “Friends and Family Testing.”

System usage was expected to reach 3000 transactions per day 3 months after the release date.

The solution never had more than 300 transactions performed by the users in one day and in 90% of the cases, known Friends and Family testers performed these transactions.

Millions of dollars were wasted to such an extent that the stock price fell considerably.

The future users were recognized as stakeholders, but an appropriate dialogue was not established with these stakeholders before it was too late.

1.7.3 The DANCOIN Cash Card Case

Another project my organization was involved with was the development and implementation of a Cash Card in Denmark—the DANCOIN case. Several worldwide-recognized patents came out of this exciting project.

The technical development was a great success. Partners such as banks, credit card facilities, and local transportation were directly involved with development and implementation.

A whole city was set up for Accept-Testing end-to-end of the integrated solution with service providers and central bank cash and transaction cost clearing. This acceptance test was a great success also seen from a publication and advertising point of view with press and television coverage.

So, why did the Danish cash card not have success contrary to basically the same card implemented in Rotterdam, Holland?

The failure to succeed occurred because of lag of communication with the corporate management people from the core stakeholder, the local transportation organization, HT:

• In parallel with the DANCOIN development HT developed its proper card and card reader device for its buses and train stations without coordinating this effort with the DANCOIN project.

• On the eve of going live, HT refused to implement a DANCOIN reader.

• Only inferior usage such as a few parking terminals, a few laundries, and some unmanned newspaper kiosks went into production.

This was not enough to pay off the DANCOIN investment and HT had enough resources to simply write off its part of the investment.

Once we have defined and agreed to the larger scope and the required activities and their leaders and managers, we are ready to build the teams for solution establishment, risk, and change management.

The method to get the teams built and to establish agreement about what the solution will be is the continued PQA process. The initial PQA Workshop invitation and the Workshop itself is the very important initiation of the PQA Process.

PQA is a core element of Strategy Quality Management. PQA ensures a precise scope definition broken down into activities, deliverables, resource requirements, process ownership, and management responsibilities.

The PQA process will most often comprise several cascading PQA Workshops and processes with specific invitations and stakeholders for each one, that is, the activities defined on higher PQA process level are candidates for their own more detailed PQA processes with focus on a partial solution delivery.

PQA is Risk Management based, but the focus is Opportunity rather than Threat.

The PQA point of departure is the client’s needs of change in his or her current situation of strength and weakness facing the stakeholders that among many others comprise clients and current and potential competition and partners.

PQA not only documents what the scope is, it also documents why the scope is defined the way it is. This ensures the agility of the PQA defined scope because if any why-case changes, then the scope must change. The organization to change the scope is explicitly defined in the PQA result.

The PQA documentation is dynamic in nature. Change management and periodic evaluation of the scope ensures that the definition of the scope of work that governs the development and implementation of the strategic initiative solutions is up to date at any point in time. For each deliverable solution component, the agreed timing, cost, and organization are precisely defined, and risk is managed.

All deliverables (solution components) are realized through three basic processes:

• Implementation that defines business functional requirements and establishes the foundation for Accept-Testing.

• Development that defines technical functional requirements and technology development, implementation, and usage.

• Quality Management that ensures that business implementers and solution developers work closely together (often face-to-face) and evaluate deliverables on a regular basis that allows for adaptation to changed conditions and gained experience in order to ensure full stakeholder satisfaction with the final solution.

1.8.1 No Excuse for Failure Principle

Much too often we have seen projects and major programs moving along with weakly defined organization of responsibility and activity defined on a level where management is impossible.

Such situations lead to crucial lack of commitment from all involved stakeholders because:

• Results do not show up.

• Results show up too late to be useful.

• Results show up without the quality that was never agreed on or documented.

The “no excuse for failure” principle implies the following:

• Involved human and technological resources are fully qualified to deliver the required and documented solution.

• The involved resources are allocated and committed in such a way that their work is done and that the results are delivered without costly interruption, delay, and cost overrun.

The “no excuse for failure” principle ensures that all involved stakeholders are visibly committed and motivated from start to close out of the strategic initiative.

1.8.2 Simulated Accept-Testing

Communication of real measurable results is performed on a regular basis during Simulated Accept-Testing (SAT), which allows the not directly involved business and development stakeholders to evaluate intermediate results.

SAT performance allows timely and pertinent decisions about required changes to take place without disturbing the progress of complete solution delivery.

The SAT communication ensures that final Accept-Testing becomes a mere formality because all involved stakeholders already know exactly what they can expect from the delivered solution components during final Accept-Testing.

1.9 ASSESSMENT AND RECOVERY OF PROJECTS IN TROUBLE

Whenever my organization is called upon by major international organizations to deliver our core services of coaching and facilitation, their strategic initiatives are in trouble. Most often, they have tried to implement a solution for months just to discover that no progress (except for spending time and money) has been achieved.

1.9.1 Medical Factory Implementation

We got involved in a major program to implement a big factory to produce medical equipment using cheap raw material to deliver an end product of high quality to be used worldwide at a price to be acceptable even to poor people.

The program was run like a project with one project manager facing several internal key-stakeholders with considerable internal power and many external stakeholders with legal and political power. The external stakeholders were delivering:

• Buildings

• Production machinery

• QA equipment

• Logistics equipment

• Internal machine control information systems

• Administrative information systems based on the SAP Enterprise Resource Planning COTS software package

The internal key-stakeholders were:

• The future factory manager

• The CEO

The work to be done was defined at a very low level (work packages by contractor) and a lot of work overlapped between contractors.

Arbitration between contractors and project manager was handled at weekly project meetings.

More and more conflicts between all parties surfaced very early. An important reason was that more than one contractor made key decisions and that these decisions were contradictory or at best not visibly aligned with the overall project objectives. This was caused by weakly defined objectives.

The project was finally declared in trouble because major deliveries were slipping without clear responsibility for the delay.

It was obvious that a program organization was needed to govern all stakeholders. Furthermore, a clearly defined unambiguous requirements specification for each contractor was needed and had to be agreed on by all parties.

Our contributions to this program that has since delivered one of the most successful solutions in the history of the pharmaceutical industry were:

• Establishment of a program organization based on visible high-level objectives (critical success factors) and clearly defined high-level activities that each one was a major project on its own. The organization, the objectives, and the activities were approved by top corporate management that became visibly involved in the program management. The project manager of the building implementation said: “This process should have been used from the beginning to avoid the troubles that started more than a year ago …”

• Coaching of the contractor responsible for delivery of the complete factory control system (a network of control computers connected to the numerical control on all production and quality control equipment).

• Our coaching comprised the establishment of the detailed project plan. We also delivered the method and coaching to develop the normalized data structure and content, and the normalized process structure common to all control computers

• The normalized data and process structure allowed fast corrections of failures and resolution of problems, and ensured an efficient interface with the SAP-based order and production planning and control environment.

• The normalized data and process structure was used and verified early in Simulated Accept-Testing to prove the efficiency of the solution to be developed and delivered.

• We coached the setup and execution of Simulated Accept-Testing supervised by corporate management (the program management team) that signed off on the solution development and implementation.

Our methods used were:

• Process quality assurance to establish the objectives and a complete project plan that allowed reliable estimation, forecasting, and tracking.

• An Information Requirements Study to identify all core objects with their purpose and usage and to ensure that they were complete with respect to the overall success factors for the program and the detailed success factors for the control system production and implementation.

• The Object Lifecycle Analysis to detail, define, and normalize all data and process objects in such a way that all control systems could be developed and implemented where needed, ensuring full integration among control computers and with external systems (numerical control and SAP).

• Simulated Accept-Testing to prove the feasibility of the data and process structure.

Both the pharmaceutical enterprise and the control system contractor coached by us implemented major method and organization improvements in order to benefit from the methods used also in the future.

1.9.2 Complete Swap of All IT Systems in a Private Bank

The new IT manager in a private bank brought us in to assess the situation (the project quality) of the biggest IT and business development program (only defined as a project) ever implemented in this (private and asset management) bank.

The task was that the old computers with COBOL-based Information Systems had to be swapped out and replaced with new technology. The old COBOL-based Information Systems were interfaced with multiple standalone solutions internally and externally. As most of the old in-house developed core-banking IT solutions were getting more and more inefficient, they were not candidates for swapping.

The corporate management had opted for a COTS standard system implemented on state-of-the-art IBM technology (including DB2 relational database) to be interfaced with the set of standalone solutions (mostly in house development) that they expected to survive and to continue to be used in business after the swap.

This COTS system was bought because a neighbor private bank used it and was relatively happy with its solution.

No requirements specifications were established.

A large number of external consultants and internal employees, mostly from IT, had spent more than 18 months with evaluation of the quality of the old solution components while trying to produce a GAP analysis (as is and to be definitions of the software that had never been documented before!).

There were no usable results from this GAP analysis.

Very expensive COTS vendor consultants were working on setting up the COTS system in the private bank even before complete requirements to solution infrastructure, security, safety, and technical environment had been defined. This was, of course, a complete waste of time and money.

In parallel with the GAP analysis, the future end users (bank employees and a few IT employees) were “trained” in the new COTS software that had not been adapted to their requirements (these requirements did not exist).

The users from business and IT were all deeply unhappy and frustrated with what they saw during training and demonstrations. This sporadic and very expensive training provided by the COTS vendor created more frustration and mistrust than learning.

IT management declared the project in deep trouble, stopped all GAP analysis and training activity, and laid off all involved external consultants. During this initial clean-up process, the relatively innocent internal project manager was removed from the project.

Once on board, we established a strategy to recover the project.

This meant, among other major changes, to involve the business organization deeply in planning and requirements specification, while preparing it for future solution implementation, evaluation, and testing.

In order to avoid the risk of losing a lot of capital on activity that does not deliver visibly useful results, we re-planned the program and the projects with a focus on real tangible deliverables—it was made Lean.

The deliverables were real solution components that could be developed, interfaced, and thoroughly tested to be satisfactory to the bank and the employees.

We succeeded in procuring external experts from major service organizations that agreed to deliver the solution components on fixed time and cost based on the solution requirements to be produced by the private bank.

The bank management committed to contribute to the solution requirements and the knowledge and the capacity of resources necessary for solution design, development, Accept-Testing, implementation, and operation.

Internal and external responsibilities were clearly defined, but it was also clearly defined that problems were resolved by mutual proactive solution contribution from all parties.

Payment to external sub-contractors could only be obtained after fully accepted delivery of solution components.

The involvement and re-motivation of the very frustrated user organizations inclusive of IT was established through usage of Project Quality Assurance that quickly visualized the key success factors and all the activities required to achieve the success factors. Success factors in this context are solution capabilities, business and work conditions, organizational competence, and events.

The user organizations agreed to produce requirements specifications quickly that could be used as a foundation for procuring solution providers and COTS-based solution components at a fixed price.

We supported the user management with an adapted and combined Information Requirements Study and Object Lifecycle Analysis that resulted in clearly defined use cases (or sprints) that were used as a basis for structuring the complete business requirements exposed to the potential service providers and sub-contractors.

In order to structure, plan, and track the progress of requirements spec production, we defined a very specific method for how to document all pertinent business processes to be supported by the COTS application and the interfaced standalone systems. To this end, we recommended use of a relatively easy workflow documentation standard that complemented our own Information Requirements Study and Object Lifecycle methods. This was relatively well accepted by the involved business users of the future solution because they had accepted that no solution could be delivered without documented requirements.

It was obvious that external experts from the COTS solution vendor and from organizations with broad and deep experience from implementing the COTS solution were required—and fast.

In parallel with the production of the requirements spec, we prepared the solicitation and tendering among potential sub-contractors. No current business process was left out or adapted in the requirements documentation, which minimized the negative impact from risk-exposed changes to known business processes. Suggested improvements to current business processes were allowed to be documented, but they could be used only for inspiration to the developers and implementers, not as requirements. In this way, we were able to present a complete solution process overview and the first complete work flow documentation very fast to the potential internal and external expert organizations that could perform development and solution implementation.

After 3 months of intensive negotiations and contracting, we had a complete project organization in place for development and implementation, where development consisted mainly in setting up and interfacing COTS applications and development of integration components. Implementation consisted of usage documentation preparation, training material preparation, user training, Accept-Testing, and operation setup.

Nine months later the first solution component went into production. Our contribution to this program comprised:

• Coaching and program management based on project management tools such as Project Quality Assurance, Project Planning with Professional Procurement, and Program Management with many stakeholders and many Work Package project managers.

• Coaching of business management with the establishment of the required physical environment for development and implementation with buildings (containers), rooms, networking, security, and IT. This resulted in a huge war room being made available to all program resources with ID card for entry and exit. For confidentiality reasons, involved development resources were only allowed to work on-site in the war room while fully supervised, while implementation resources from IT and business could work in their own environment when they prepared training material and system operation procedures.

• Establishment of the program organization and the project teams with more than 100 resource persons of whom more than 50% were working full time on the program.

• Progress tracking that was performed once a week with all involved project managers.

• Handling of any cross-organizational issues on a day-to-day basis at 8:30 meetings in the war room.

• Functional implementation issues were analyzed using Object Lifecycle Analysis to ensure a complete and consistent solution implementation.

• Simulated Accept-Testing was established between internal future support, external solution implementers, future end users, and, to some degree, internal management.

• The end users were only formally trained once the future solution components were ready for final Accept-Testing and production.

Frustration was avoided, confidence was re-established, and to some extent, the stakeholders were happy. Unfortunately, it was not possible to cope with all technical issues concerned with the bought COTS software, but that is another story.

1.10 STRATEGY QUALITY AND SUCCESSFUL STRATEGY

Quite often, the corporate strategy is confounded with the corporate objectives or the corporate vision, but the objectives and vision cannot be the strategy on their own because the strategy is also the way, the method chosen to meet the objectives and make the vision come true, that is, the strategic initiatives.

Strategy is not confined to decision making on a board or government level, it is just as much based on decisions made by a department, a ministry, a business unit, or a cross-organizational project or program organization performing strategic initiatives.

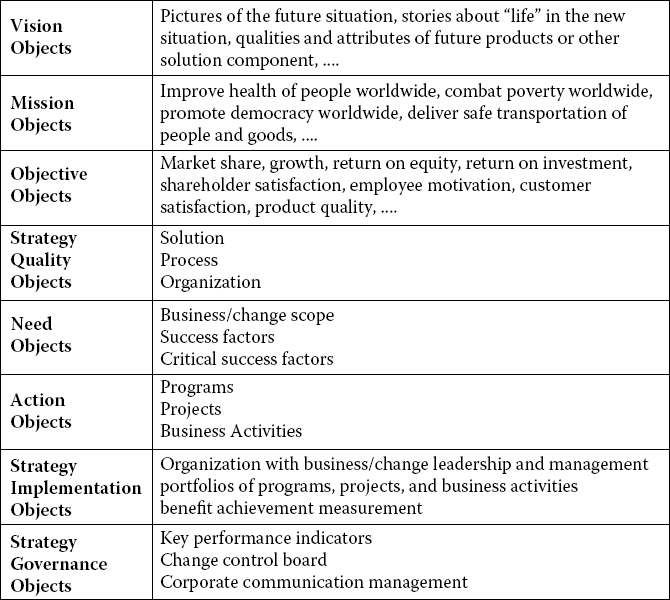

The way from corporate visions and objectives to governance of the corporate strategy that fulfils the corporate mission and makes the stakeholders happy is outlined in the simple model shown in Figure 1.5—starting from the top and moving down:

High quality strategies have all objects in the model defined, visibly agreed to by the stakeholders, and documented in order to ensure efficient communication of objectives and measures to be taken by all strategy stakeholders.

1.10.1 Strategy Quality and People

People implement the strategy by explicit definition of, and agreement to, all the quality objects shown from initial visions over performance of projects, programs, and business activity to strategy governance.

FIGURE 1.5

Quality objects from vision to strategy governance.

The choice of the people involved in a strategy is critical for the quality of the results that can be obtained by following the strategy.

Although this seems obvious, the attention to the choice of people to be involved with a strategy and strategic initiatives is much too often very low and based on the first available opportunities among friends and colleagues.

Once the choice of people to be involved in a strategy has been made and accepted, the leaders and managers must wait for major blunders or failures from a bad choice of people before a change for the better can be made.

It is very difficult to replace people on teams, especially the people leading or managing the teams, because the people that are asked to leave quite often interpret this as a personal defeat. The people that stay often regard the replacement as a management failure or weakness, which raises their suspicions of further blunders to come.

1.10.2 Strategy Quality and Risk

The result of strategic decisions is not always the fulfillment of the objectives that originally led to the decisions. When a result is accepted to be better than the objectives originally established, everything is fine—we can talk about a successful strategy, but it is not sure that we are facing a high quality strategy.

Pure luck is playing an important role in strategy and strategic initiatives because results of strategic decisions are aleatory.

Only when we visibly apply risk management and visibly control the direct outcome of our strategic initiatives from initiation to final implementation and governance can we talk about high quality of the strategy.

You can recognize a high quality strategy by the fact that the results correspond to the objective that has visibly (i.e., documented) been adjusted to what the stakeholders need and expect in the end.

1.10.3 Strategy Quality and Leadership

I will not evaluate leadership on any scale because all leaders—as it also holds true for people in general—have their own style.

There are, however, certain common characteristics of successful leaders, such as their ability to communicate with the purpose to:

• Listen

• Sell an idea

• Motivate others

• Navigate

These communication capabilities allow leaders to drive strategies through to success, even though the final result is quite different from the one envisioned when the original objectives were set.

The corporate leaders envision the initial strategy objectives, but the chosen teams involved with the strategic initiatives define the final objectives. The corporate leaders play an important role as listeners and promoters of change for the better.

One example of an excellent leader is the Danish Prime Minister Jens Otto Krag, who succeeded in getting Denmark into the European Union in 1972 with a very small majority.

Jens Otto Krag said something in 1966 that places him as one of the first documented agile leader personalities with strong navigation capability seen from a modern standpoint:

“You have a point of view, until you take on a new one.”

In 1966, many interpreted this expression as outrageous, while others were confirmed in their perception of Jens Otto Krag as a pragmatic politician who knew how to navigate.

The leaders do not make decisions too often; they make sure that the teams involved with their strategic initiatives are established in such a way that they can operate efficiently and make appropriate decisions by themselves within the scope of the initiative.

We will look deeper into team building in the next chapter.

Once an idea is born, it is the foundation for even better ideas—if you share it.

We learn as much from clients and partners as they learn from us.

We are here to have fun, not to live in fear that someone will steal our ideas.

The presented standards are specific methods and techniques used by my companies, which is rarely the case with the public standards that refer to best practice, but do not show what this best practice is.

We present why and how we have done something. The public standards present what to do and to some extent why, but only in rare cases how.

Enterprise Information Systems, Business Behavior, and Business Organization are continuously kept synchronized and adapted to the environmental conditions and opportunities in order for the enterprise to obtain the maximum benefits from technology, market opportunities, knowledge, and experience.

Strategic initiatives comprise most often planning, development, and implementation of new Information Systems and adaptation to already implemented ones.

Corporate leadership establishes the strategy of a corporation. The strategy tells you why the organization has been established the way it is.

The Strategic Initiatives establish the why, the what, the when, the how, and the who concerned with sustaining, changing, and improving business procedures and infrastructure in support of the corporate strategy.

The Agile Quality Management standards used in strategic initiatives comprise:

• Identification and activation of stakeholders to be involved

• Communication

• Team building

• Decision making

• Documentation

The agile ongoing quality assurance of the solution, the organization, and the processes of a strategic initiative has contributed to the success of the methods used.

The agility is there to overcome the constraints of mistrust and suspicion among strategic initiative stakeholders. The core agility principle is:

Each process from the definition of the initial need for change to the final delivery of the agreed solution contributes to stakeholder trust, mutual respect, motivation, and willingness to take ownership of the solution components delivered.

The first action in the establishment of a strategic initiative scope is to identify the initial objective of the sponsor and the initial keystakeholders to be involved with the initiative. You respect that you do not know what the real scope is—yet.

When establishing a strategic initiative, you make a serious effort to get to know all the stakeholders that are concerned, that is, to have a dialogue with key persons and organizations that potentially could benefit or suffer from it. This is especially true for the less visible and less obvious stakeholders such as unions, politicians, government, legal bodies, and potential competitive businesses and partners.

Once we have defined and agreed to the larger scope and the required activities and their leaders and managers, we are ready to build the teams for solution establishment, risk, and change management.

The “no excuse for failure” principle implies:

• Involved human and technological resources are fully qualified to deliver the required and documented solution.

• The involved resources are allocated and committed in such a way that their work is done and that the results are delivered without costly interruption, delay, and cost overrun.

Simulated Accept-Testing allows timely and pertinent decisions about required changes to take place without disturbing the progress of complete solution delivery.

The objectives and visions cannot be the strategy on their own because the strategy is also the way, the method chosen to meet the objectives and make the vision come true, that is, the strategic initiatives.

It is very difficult to replace people on teams, especially the people leading or managing the teams, because the people that are asked to leave quite often interpret this as a personal defeat. The people that stay often regard the replacement as a management failure or weakness, which raises their suspicion of further blunders to come.

You can recognize a high-quality strategy by the fact that the results correspond to the objective that has visibly (i.e., documented) been adjusted to what the stakeholders need and expect in the end.

The leaders do not make decisions too often, they make sure that the teams involved with their strategic initiatives are established in such a way that they can operate efficiently and make appropriate decisions by themselves within the scope of the initiative.