82

10001500

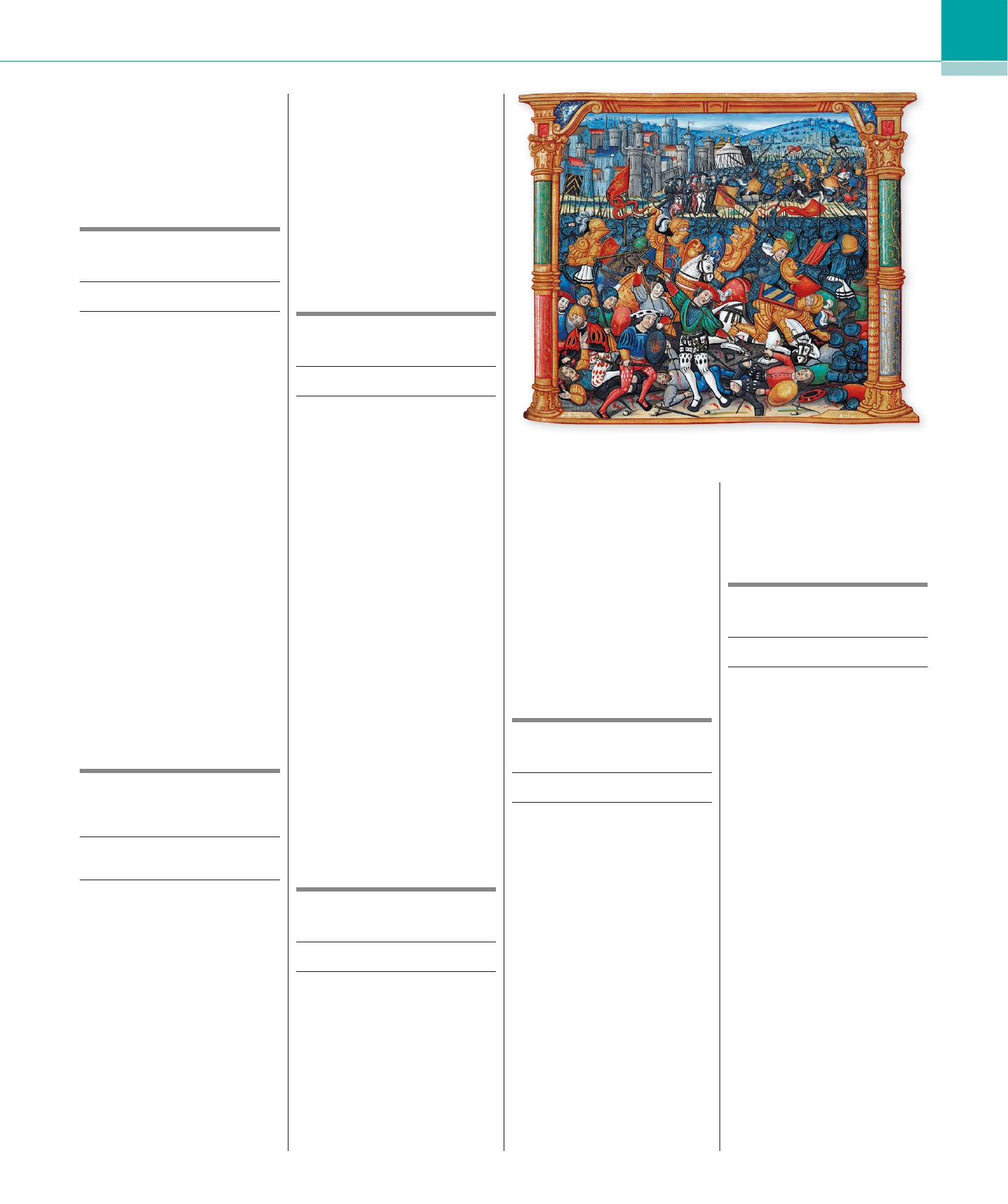

Shown here in a 15th-century illumination, the Battle of Courtrai saw the victory of an all-infantry

Flemish army over a French mounted army.

LEGNANO

GUELPH AND GHIBELLINE

CONFLICT

1176

■

NORTHERN ITALY

■

LOMBARD

LEAGUE VS. HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

In the late 12th century, northern Italy

was divided by ghting between the

Guelphs, supporters of the papacy, and

the Ghibellines, supporters of the Holy

Roman Emperor. In 1167, the major cities

of Lombardy formed a league, with

papal approval, to defend themselves

against Emperor Frederick Barbarossa,

who engaged in ve campaigns to

combat them. After failed peace talks in

May 1176, Frederick led his 3,000-strong

army around Milan to meet with

reinforcements from Germany at Lake

Como. The Lombard League deployed

3,500 men to intercept him north of the

city at Legnano, where they positioned

themselves around the Carroccia, Milan’s

sacred battle wagon. The erce battle

that ensued was evenly matched until

eventually the Lombard League’s cavalry

regrouped and attacked, scattering the

Imperial army. The Imperial cause in

Lombardy was damaged, and in 1183

Frederick had to concede self-

government to the cities there.

XIANGYANG

SONG–YUAN WARS

1268

■

CENTRAL CHINA

■

MONGOLS

VS. SONG FORCES

In 1267, Kublai Khan, the Mongol Great

Khan, turned his attention to conquering

southern China. His key objectives were

the twin fortresses of Xianyang and

Fancheng; these controlled the Han river,

which fed into the Yangzi, in the heart

of the Song empire. Despite their huge

forces, the invading Mongols were

thwarted by the defenders’ ability to

resupply the fortresses’ garrison using

hundreds of river junks. The Mongols’

attempts to build ramparts in the river

to dam it failed, as did outright assault,

and the siege dragged on for ve years.

Finally, Kublai Khan obtained heavy siege

catapults from his nephew, the Ilkhan

of Persia. The projectiles hurled by

these catapults broke down Fancheng’s

wall within a few days and it fell to a

Mongol assault. Seeing the battle was

lost, the Song commander of Xiangyang

surrendered. With the fall of both

fortresses, the way into southern China

was clear and Song morale collapsed. By

1279, Kublai Khan had completed his

conquest of southern China.

3COURTRAI

FRANCO–FLEMISH WAR

1302

■

MODERNDAY BELGIUM

■

FRANCE VS. FLANDERS

In 1302, the towns of Flanders were

in revolt against ve years of French

occupation. To quell this uprising, Philip

IV of France sent an 8,000-strong force

to Courtrai, north of Tournai, where the

Flemish were besieging a castle. The

Flemish militia, armed with pikes,

crossbows, and goedendags (pikes with

a club mounted on the end) took position

in an area of marshes and small streams.

When the French knights charged, they

became bogged down in the marshes and

were knocked from their horses by the

Flemish goedendags. The remaining

knights retreated and the French infantry

ed, pursued by the victorious Flemish.

Over 1,000 French soldiers died, including

many knights whom the Flemish chose

not to keep for ransom. The encounter

became known as the “Battle of the

Golden Spurs” for the quantity of valuable

spurs looted from their corpses, and

showed that drilled foot soldiers could

overcome mounted knights; however,

later French victories denied Flanders

its independence.

BANNOCKBURN

FIRST WAR OF SCOTTISH

INDEPENDENCE

1314

■

SOUTHERN SCOTLAND

■

SCOTLAND VS. ENGLAND

Robert the Bruce took the Scottish

throne in 1306 and led a military

campaign to drive out the English,

who had gained control of many areas

of Scotland following Edward I’s invasion

in 1296. By 1314, Stirling Castle, the

only remaining English stronghold, was

under siege by the Scots, and Edward II

led an army of about 2,500 cavalry and

15,000 infantry to defend it. The English

army was met by an 8,000-strong force

of Scots (mainly infantry) in the New

Park, south of the town. The battle

lasted for two days—English cavalry

charges were unable to penetrate the

Scottish formations of spearmen, and

when the English pulled back they fell

victim to pits and ditches that the Scots

had laid in the marshy ground. A hasty

retreat by the English saw 34 barons

killed, along with thousands of soldiers.

Stirling Castle fell and the English never

recovered their positions in Scotland,

ultimately having to recognize Scottish

independence in 1328.

POITIERS

HUNDRED YEARS’ WAR

1356

■

CENTRAL FRANCE

■

ENGLAND

VS. FRANCE

In 1355, an eight-year truce in the

Hundred Years’ War between England

and France expired. While Edward III

attacked northern France, his son

Edward, the Black Prince, led a force

of 8,000, including about 2,500

longbowmen, north from Aquitaine on a

raid into central France. The French army,

led by King John II, crossed the Loire to

intercept the English, and the two armies

met just east of Poitiers. Outnumbered by

the French, the English army positioned

themselves on a narrow front protected

by a marsh and stream. An initial French

charge faltered under a series of volleys

from the longbowmen and the retreating

knights were forced into hand-to-hand

combat. They attacked again, but the

Directory: 1000 –1500

US_082-083_Directory_Chapter_2.indd 82 06/04/2018 16:04

83

DIRECTORY

◼

1000–1500

Depicted here in a 16th-century miniature, Nancy was the nal and decisive

battle that ended the Burgundian Wars.

English led a surprise advance and

the French army disintegrated. Many

French knights were captured, including

King John. A weakened France was

forced to agree to a treaty in 1360

expanding English holding around

Aquitaine and Calais.

LAKE POYANG

RED TURBAN REBELLION

1363

■

EASTERN CHINA

■

MING

DYNASTY VS. HAN DYNASTY

The Mongol Yüan dynasty of China had

collapsed by the early 1360s, and three

principal contenders for power emerged:

the Han, the Wu, and the Ming. The Ming

arose out of a smaller rebel group, the

Red Turbans, and in 1363 their leader

Zhu Yuanzhang began consolidating his

power around the Ming capital, Nanjing.

When the Han attacked the Ming-held

town of Poyang using a eet of large

warships positioned on the adjacent

lake, Zhu sent what reinforcements he

could. The Han commander failed to

block the lake entrance, allowing a Ming

eet in, but the smaller Ming ships

struggled to surround and board the

Han vessels. Instead the Ming used re

ships to attack the Han eet, burning

many ships. The Han retreated and

much of their eet was destroyed

trying to ee the lake. Poyang was

soon relieved by land and Zhu, with

Han power broken, emerged as the

dominant force in China, declaring

himself emperor in 1368.

KOSOVO

OTTOMAN WARS IN EUROPE AND

SERBIAN-OTTOMAN WARS

1389

■

MODERN-DAY REPUBLIC OF

KOSOVO

■

SERBIAN-BOSNIAN ARMY

VS. OTTOMANS

The Ottoman Turks had made

signicant advances in the Balkans in

the 1370s–80s, absorbing Bulgaria and

taking the important Serbian town of

Niš. Serbia itself had been weakened by

civil wars, but in 1388 the ruler of the

northern part, Prince Lazar, defeated

the Ottomans, provoking their leader,

Sultan Murad I, to retaliate. The Ottoman

army of up to 40,000 men paused

at Kosovo, where Lazar had a force

just over half the size, including

reinforcement troops from another

Serbian nobleman, Vuk Branković.

Ottoman archers rebued an initial

Serbian charge, but the Serbs still forced

the Ottoman center back. The Ottomans

then launched a full counterattack that

destroyed the Serbian center: Lazar

was killed and Branković withdrew

from the eld with the surviving Serbian

forces. Losses on both sides were vast,

but Serbia, with fewer resources, was

unable to resist subsequent Ottoman

advances; it became an Ottoman vassal

in 1390, and nally lost its

independence entirely in 1459.

CASTILLON

HUNDRED YEARS’ WAR

1453

■

SOUTHWESTERN FRANCE

■

FRANCE VS. ENGLAND

In 1435, the English were abandoned

by their Burgundian allies, leaving

them to continue the Hundred Years’

War against France alone. By 1451,

the French under Charles VII had

recaptured all their lost territory except

for the city of Calais, but in October

1452 the Earl of Shrewsbury seized

Bordeaux with an English force of

3,000 and advanced inland. The French

countered by besieging the strategic

town of Castillon, where the English

confronted them on July 17, 1453.

Although reinforcements had doubled

the size of the English army, the French

had built a temporary defensive

fortication with over 300 eld guns.

When Shrewsbury impetuously gave the

order to charge, he and his men were

destroyed by waves of cannonballs. With

their commander dead, the English

retreated and were slaughtered by the

advancing French. Bordeaux fell to

the French soon afterward, leaving

England again in possession of just

Calais and bringing the Hundred Years’

War to an end.

MURTEN

BURGUNDIAN WARS

1476

■

WESTERN SWITZERLAND

■

OLD SWISS CONFEDERACY VS. BURGUNDY

The steady advance of the Duchy of

Burgundy’s army down the Rhine in the

1460–70s brought it in conict with

the ercely independent Swiss cantons

(allies of the Holy Roman Empire). In

1474, war broke out between the two

sides, and Charles the Bold, Duke of

Burgundy, led a series of invasions into

Swiss territory. Burgundy’s army was

defeated by the Swiss Confederate army

at Grandison in March 1476, but during

the following June, Charles led an attack

on the town of Murten. The Swiss

cantons assembled a force of around

25,000 soldiers armed with pikes to

relieve the siege. The Burgundians were

caught by surprise, and though they had

occupied the side of a hill with artillery

the Swiss pike formation pushed

forward and forced the Burgundian army

into retreat during which thousands

were killed. Charles ed with his

remaining troops back to Burgundy.

1NANCY

BURGUNDIAN WARS

1477

■

EASTERN FRANCE

■

OLD

SWISS CONFEDERACY VS. BURGUNDY

In 1477, Charles the Bold, Duke of

Burgundy, laid siege to the strategic

city of Nancy in Lorraine. The region,

formerly under his control, had broken

away under Duke René. Charles led a

mixed force of Burgundians, Italians,

and Dutch, while Duke René countered

with 20,000 troops, half of them

Swiss mercenaries. The outnumbered

Burgundians tried to reduce their

disadvantage by positioning themselves

along a narrow front protected by

a stream and thick woods. But the

Swiss phalanx advanced, pushing the

Burgundian left wing back and, crucially,

displacing their artillery. Although

Charles tried to redeploy troops to

plug the growing gaps, the Swiss

superiority in numbers overwhelmed

the Burgundian army which collapsed.

Charles was killed, making René’s victory

complete, and the Duchy of Burgundy

fell apart—one portion went to the

Austrian Habsburgs, and the remainder

was taken over by Louis XI of France.

BOSWORTH FIELD

WARS OF THE ROSES

1485

■

CENTRAL ENGLAND

■

HOUSE

OF LANCASTER VS. HOUSE OF YORK

The Wars of the Roses, fought between

rival claimants to the English throne the

Houses of York and Lancaster, seemed

to have ended in 1471. The controversial

accession of the Yorkist Richard III in

1483, however, reignited the conict.

Many nobles ocked to support exiled

Henry Tudor, the remaining Lancastrian

candidate. In August 1485, Henry landed

at Milford Haven in Wales. He advanced

into England, and while he gathered

reinforcements Richard rushed to head

him o. At Bosworth, near Leicester in

central England, the two armies met.

Although Richard’s army was larger,

contingents under the Earl of

Northumberland and Lord Stanley

remained slightly apart from the main

force. When an attack by Henry’s army

put pressure on Richard’s line, the king

ordered Northumberland to join him,

but the Earl refused. Stanley allied

with the Lancastrians which led to a

Yorkist retreat, during which Richard

was unhorsed and killed. Henry was

crowned and later married Richard’s

niece, Elizabeth of York, to unite the

Yorkist and Lancastrian dynasties.

US_082-083_Directory_Chapter_2.indd 83 06/04/2018 16:04

US_084-085_Opener_Chapter_3.indd 84 06/04/2018 16:04

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.