Chapter 6

Planning to Buy Knowledge

Due Diligence Issues

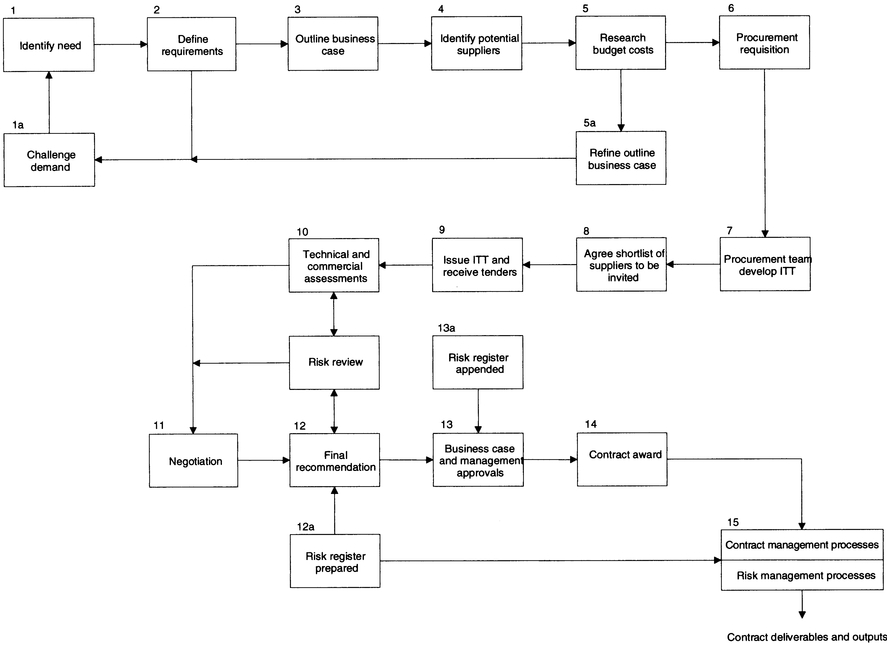

In this chapter, attention is given to best practice procurement of knowledge. Readers may wish to use this as a benchmark of whatever procedures are currently used within their organization, adopting and adapting as appropriate. The chapter follows the process in a logical sequence from need identification, through requirements definition, invitation to tender (ITT), negotiation, business case development and contract award. Plainly, not all these elements will be present in every case, but it is a useful theoretical starting point to examine the process as it impacts knowledge purchasing (see Figure 8).

Previous chapters have suggested some background strategy issues that need to be considered. At this stage it is assumed that the client organization has evaluated alternative options (in-house knowledge development, joint venture R&D, collaborative work and so on), determined its strategy on IPRs, (ownership, background and foreground rights) and is now embarking on the knowledge 'purchasing' process as the best option in the circumstances.

Organizations wanting to undertake a thorough review of their services procurement activity may wish to refer to The Outsourcing R&D Toolkit,1 which contains a very detailed treatment of procurement aspects of contracting for R&D services, a subject that bears many similarities to purchasing other knowledge-based services.

The concept of due diligence is of increasing importance today. Whilst it has a specific legal meaning, normally in relation to the officers of a company, the concept has been expanded to include all those things an organization should do in order properly to discharge its obligations to its various stakeholders. In practice this means ensuring as far as is reasonably practical that desired outcomes will be achieved. In the field of acquisition of knowledge, due diligence will equate to properly and adequately defining the work to be done (knowledge to be delivered), making sensible checks of the proposed supplier and then ensuring that any resulting contract is properly managed, in accordance with modern best practice. Due diligence is relevant not only to companies but to all organizations and the individuals that work within them. In this chapter we have broken down the due diligence process into those activities

Note. Stages 1-5 are sometimes called the project assessment phase. Figure 8 Buying knowledge – a generic procurement process

required both before a contract is entered into and then the activities to be done whilst a contract is underway.

Vendor Assessment

In any buying and selling situation, each party makes a provisional assessment of the other's status as a business partner. For the buyer the standard questions are, will this supplier be a reliable partner, delivering what I want, when I want it, at a price I can afford? For the seller, will this client be a reliable partner, telling me all I need to know in order to satisfy my order properly? Will the client become a nuisance during our relationship and will they pay me on time?

In the field of commercial purchasing, seller or vendor assessment is an important task for the buying organization. An organization buying knowledge must evaluate the potential supplier before committing to any substantial contract. So what does a client organization need to know about a potential knowledge supplier and how do they go about obtaining the necessary information and data? Indeed, who should undertake this work? To answer these questions in reverse order:

Who should undertake vendor assessment?

This is an activity to be undertaken in a systematic and methodical way. The factors to be evaluated are the technical, technological and professional credentials of the potential supplier, its facilities, management competence/track record and its financial stability. It is strongly recommended that this is a team effort, unless the knowledge buyer has available an individual of exceptional breadth and depth of experience covering both technical and commercial activities. This activity should be overseen by a senior manager to ensure it is given the attention it deserves.

How does the team go about collecting the necessary information?

This is a matter both of searching for information and expecting the supplier to be candid with information to enable the evaluator[s] to do this job properly. Obviously, if the supplier is hungry for work or believes they may lose business they are more likely to cooperate.

Assessment is an ongoing process. At least three stages are identifiable:

- Pre-contract – buyer sets out strategic requirements. Potential supplier produces a proposal or agrees to the buyer's specification of work to be done.

- During contract – buyer monitors technical and administrative performance.

- Post-contract – review achievement of objectives (joint review or internal review-or both).

It is necessary to ask probing questions at each stage:

- Pre-contract – What do we want from the knowledge to be purchased? What alternatives do we have? How will we use the knowledge?

- During contract – Do we wish to change the objectives? Are we achieving the objectives? Should the work continue? How is the supplier's team performing – are personnel changes required?

- Post-contract – Did we succeed? Did we get good value for money? Did we utilize the knowledge? What if we had done nothing?

These stages are, as suggested above, analogous to supplier assessment and monitoring in any other purchasing situation. A pre-contract 'visiting group' may be constituted to carry out a detailed assessment of work planned and progress made – it looks at the organizational mission or objectives of the knowledge vendor and at its past achievements. It examines quality and productivity of the potential supplier, at its internal monitoring procedures and may supplement its findings with peer reviews. Typical assessment techniques of specific relevance to knowledge procurement are:

- visiting group/peer review

- level of external funding – if a not-for-profit supplier

- extent of collaborative work

- staff profiles (age/turnover and so on)

- measures of efficiency (overheads per employee, productivity per employee, project completion rates, publication review)

- patent and royalty review

- customer review.

Most of these reviews are self-explanatory and merely require the client to devise the necessary format of question appropriate to the situation.

Vetting potential suppliers as potential information security risk

Preventing valuable information from being lost, leaked or misappropriated is difficult: industrial espionage is a growth area. The R&D activity of a company can give vital clues as to its financial strength and the future products or processes which it may introduce. It can also give an early indication of strategic policy changes and so is a key area of investigation for those involved in systematically assessing their competitors.

Security is a sensible area to review when undertaking a supplier assessment exercise. Ask to see a copy of the potential supplier's security policy, quiz their staff as to their understanding of their policy, see how it is implemented in practice, ask about other work that they are doing at the present and see how much they reveal. Obviously this need not be done in too overt a manner (not on the first visit) and nor need the potential supplier's failure in this vital area necessarily preclude it from working for you. It will, however, place you in a good position to discuss with the potential supplier any security risks you perceive and encourage you to work together to identify and implement any necessary improvements to security.

Information sources

There is a range of information sources available to the assessment team, which should decide at the outset which sources will be used:

- the knowledge seller's own client register, if available – take references;

- the knowledge seller's main subcontractors, if any – ask for their main point of contact and explain that the purpose is to evaluate the interaction of those parties who may be working together on your project;

- government, local authorities and professional bodies' information departments;

- the knowledge seller – use of a standard questionnaire is suggested;

- trade press, company search agents, Dun and Bradstreet service and so on.

Technical appraisal

Information required will vary from project to project. The following categories are suggested:

- Capability, management, technical resources, quality control procedure, parent company involvement/support, location, industrial relation records, safety policy.

- Present capacity: can the potential supplier undertake the work properly bearing in mind constraints of current workload? Consider plant, equipment and staff availability.

- Related experience: what has the potential supplier done that is equivalent? Has the potential supplier worked for you before?

- Availability: can the potential supplier meet our planned programme? What guarantees are they prepared to give?

- Finance: unprofitable or under-financed suppliers may be a source of problems to the client. In extremis there may be a case for obtaining a bank or other guarantee, or having advanced funds held in a trust arrangement to obviate misappropriation of funding.

Competitive Tender or Negotiation?

This is a basic choice that confronts every 'buyer' in any commercial purchasing situation. Each has recognized advantages and disadvantages. In the field of knowledge-buying and management consultancy, however, there is often a reluctance to utilize true competitive tendering, partly because it is felt that this is too blunt and grubbily commercial an approach to take in a situation where the knowledge buyer seeks to utilize the very best resource available and where the field of expertise may be very small. It is also, in part, because many management professionals, who are effectively the 'knowledge buyer' on behalf of the client organization, believe that they know the field sufficiently well to identify the best potential supplier without testing the market. They believe that the decision is already made and, in effect, cannot be influenced.

Advantages of Competitive Tendering

- Competing firms know, unless post-tender negotiation is allowed under the tendering rules, that they must tender their optimum bid at the outset in order to progress through to more detailed consideration (under some competitive tender arrangements, a contract may be awarded on the strength of the receipt of tenders with no further evaluation). This arguably means that the best technical and commercial 'fit' emerges early in the overall negotiation process.

- It encourages competitors to be creative in suggesting alternative commercial and technical solutions to the client's requirement (providing the rules of the competitive tender expressly encourage alternative bids).

- In principle a competitive tender against the client's technical specification gives the client some confidence that he or she is comparing 'apples with apples' in evaluating the tenders.

- This can be a very fair way of choosing between competitors in principle, denying any advantage to one over another.

- May make the potential supplier more amenable to trading on the terms and conditions that accompany the ITT document – in other words, it strengthens the buyer's negotiating position.

Disadvantages of Competitive Tendering

- If the client organization selects the wrong group of tenderers, it is likely to get a suboptimal solution to its knowledge requirement.

- Where handled incorrectly, a competitive tender may create or reinforce a climate of expectation in the mind of the client that is suboptimal in terms of its requirements.

- Collusion between tenderers is possible, especially if an open pre-tender meeting has been held.

- The process is time-consuming and expensive, particularly to potential suppliers who must prepare a detailed bid with a less than even chance of winning the work.

- Selection of the same group of bidders on a number of occasions may self-perpetuate the 'victory' of one over the others, leading to lack of commitment on the part of the others.

- It may discourage the best companies from bidding if they feel they have little chance of winning the tender.

The most potent argument against the use of competitive tendering, and in favour of a negotiated approach to contract for buying knowledge-based services, is that competitive tendering militates against building a long-term relationship with contractors. So-called 'partnership sourcing' has obvious advantages in a situation where the knowledge buyer wishes to build the interest and commitment of the potential supplier, encouraging it to identify with the client's needs, limiting the number of suppliers through whom the client's IPRs may leak, and enhancing useful personal interaction between the client's and the supplier's technical teams.

Confidentiality of information prior to issuing tender enquiries

One aspect of competitive tendering that is more complex in a knowledge-buying situation than in ordinary commercial settings is the need for confidentiality. Most ITT documents will have confidentiality undertakings incorporated, but this is of little use where, for example, a prospective tenderer declines to make an offer – effectively they will have seen your specification but will be under no obligation to secrecy.

A partial answer to this problem is to enter into a confidentiality agreement with prospective tenderers in advance of their receipt of an ITT document – in other words, if you do not sign up, you are denied the opportunity to bid. Indeed the preceding vendor evaluation process may be made subject to a confidentiality agreement under which the potential supplier agrees not to misuse information about the prospective client to which they are made privy. The problem with all confidentiality agreements, however, is that they are difficult to enforce because proof of information leakage is often impossible. Once information exists, it is likely to leak sooner or later.

Specifying the Work

The format of the specification of work will depend on the information to be imparted by the client to the supplier. In the interests of confidentiality there may be a case for preparing two specifications, one in sufficient detail to invite and receive tenders and the other suitable as the basis of the contract. Either way, the specification will cover:

- background to the requirement

- statement of work-scope of work

- timescales or milestones

- project management/administration

- knowledge-transfer targets to be achieved

- documentation to be provided

- technical liaison.

Essential Qualities of Good Specifications

- Completeness: the purpose of the specification is to define - it must therefore be specific. Nothing of importance should be omitted or left to the discretion of the reader.

- Relevance: it is important that the specification does not contain extraneous detail.

- Unambiguousness: If the client is unclear about what he requires, the specification is not the right place to attempt to clarify his thoughts!

- Adequacy: The specification must specify what is required, but not add unnecessary detail. In some circumstances a performance specification, detailing only outputs required from a process, may be better than a detailed technical specification which sets close parameters on all aspects of the work.

A specification is a description in precise terms. It is a part of technical writing which is a branch of literature, not technology. A good specification should normally be intelligible to technical non-specialists, bearing in mind it may well be non-specialists (such as lawyers) who have the final say on the interpretation of the specification! It can be helpful to think of the conditions of contract as being part of the specification, albeit they are normally in a separate document. The technical part of the specification defines what is to be done, the commercial part of the specification (terms and conditions) defines how the project is managed commercially.

Timescales

It is undesirable for a contract to be open-ended as to its period and a timetable of some kind is normally required. This does not, of course, mean that the timetable cannot later be adjusted if the work proves to be more difficult than anticipated or if promising new avenues of work become apparent.

Standard of Work

The manner in which the work is carried out is ultimately laid down (in an English Law context) by reference to the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982 which provides that 'In a contract for the supply of a service where the supplier is acting in the course of a business, there is an implied term that the supplier will carry out the service with reasonable care and skill.' The supplier must act with at least the care and skill expected of an ordinary man and, if claiming particular expertise, as knowledge contractors may be presumed to do, then the standard of care and skill rises accordingly.

Project Management/Administration

The supplier will often wish to define its right to manage the project on a day-to-day basis. The client usually will want, for technical and due diligence reasons, to see how its money is being spent and have some influence over the course of the work, especially when knowledge-transfer lies at the heart of the contract. In practical terms it may be appropriate for each party to appoint a project manager, who are the normal point s of contact for the two organizations.

Contract Pricing Strategy

There is a number of potential contract pricing 'strategies' that may be available to a buyer. The real difference between these contract strategies is the relative distribution of financial risk between the seller and the buyer. To put this in context we will look briefly at the possible range of strategies and then see how these apply in an knowledge purchasing situation. The descriptions used are those found in commerce generally:

Fixed Price

Here it is necessary that work can be accurately foreseen/measured and that commencement and completion dates are not subject to change. The advantage is that buyers know their extent of financial liability from the outset, which assists budgeting. Contractual supervision is usually minimal. Disadvantages are that if the contractor hits problems they may be put at risk in terms of losses; this in turn may put the buyer's project and/or programme at risk.

Firm Price

The requirements are as for the fixed price, except that the price, or part of it, is linked to an inflation formula. Useful on longer-term projects as it removes the need for cost forecasting. There is a benefit to the contractor who does not carry the risk of inflation as well as other risks. May require extra administration in terms of cost variation formulae and claims.

Schedule of Rates (Sometimes Called Time and Materials)

Similar to re-measurement/bill of quantities except that an agreed schedule of labour and materials rates is agreed at the outset. This may be linked to an inflation escalator. Same disadvantages as firm price strategy above, especially extra administration by the client organization.

Part Fixed Price, Part Schedule of Rates

Minimizes the disadvantages as set out above by making a part of the contract price fixed. The buyer tries to maximize the fixed part; the seller may try to minimize it.

Cost Plus Percentage

Advantages are that minimal specification is required and work can be got underway quickly. The buyer must have high confidence in and trust of the contractor and the contractor is used in helping to plan the work. A 'cost plus' strategy is not often recommended because there is every incentive for the contractor to inflate the cost to increase the percentage fraction (effectively the profit) earned by him or her. Cost plus strategy increases the buyer's burden of supervision.

Cost Plus Fixed Fee

Similar to cost plus percentage, except the fee is fixed, so there is no incentive to inflate costs. There is, however, no incentive to minimize them either, as someone else pays the bill!

Negotiated – Open Book

This requires negotiation with the supplier, with open accounts and an agreed method of making books available. It requires some financial expertise and a high degree of trust and confidence between the parties. One advantage is that it is helpful to the buyer who in non-competitive situations obtains knowledge of the contractor's pricing methods. Companies in competition with others are amenable to this method as they perceive it as increasing their chances of getting the work. Companies that know they are in a non-competitive situation resist this approach. Another disadvantage is that there is less incentive for the contractor to minimize costs.

The Need for Effective Project Management

We have noted the importance of effective technical and financial control. How is this actually achieved? First and foremost, the Conditions of Contract should support the project management concept. In other words they contain provisions setting out who does what in terms of management and the remedy procedure where disputes or problems arise. The Conditions of Contract or the technical specification should clearly lay down a project management methodology involving:

- Monthly (or periodic) reports.

- Named and numbered technical reports to be submitted at key milestones.

- A 'Project Memo system' to enable tracking of technical and programme communications.

- On a particularly long or complex project, periodic project reviews held at the supplier's premises to thoroughly review all aspects of the contract actions arising are clearly recorded and systematically reported in succeeding monthly (or periodic) reports.

This piroject management methodology is usually set out in the technical specification or appended to it as appropriate. We turn now to review these elements in detail.

Monthly Reports

These cover:

- Activities undertaken during the month – what has been done, preferably with reference to the technical specification.

- Achievements during the month – milestones achieved, with reference to the technical specification.

- Knowledge-transfer activities – this should be related to the client's specification and show progress towards the client's knowledge transfer requirement.

- Where applicable, subcontract progress – it may be appropriate to append the subcontractor's equivalent monthly/periodic report to the supplier's report.

- A review of Project Memos and any outstanding issues.

- Project Finance report – this may be considered unnecessary on a fixed price contract.

Named/Numbered Milestone Technical Reports

Irrespective of the monthly reports, the project will have a number of milestones set out in the technical specification and these are separately reported. Such milestone reports set out overall project progress and any deviations from the agreed programme. Milestone reports are key contractual events, to which progress payments are likely to be attached. They are named and numbered to facilitate communication at all stages during the project – in other words each report is referred to by its name or number which serves as a focus for both the supplier and the client. Milestone reports cover each distinct/discrete phase of the project as suggested in the following example:

End of Phase 1 – Project definition

End of Phase 2 – Data analysis

End of Phase 3 – Preliminary design

End of Phase 4 – Knowledge-transfer phase 1,2,3 and so on

End of Phase 5 – Submission of final contract deliverables.

Milestone reports are not used as a vehicle for advising of serious technical or programme delays, or cost increases, although such issues may be referred to. These issues are to be reported in real time and the monthly report is the correct vehicle for this – alerting the client at the earliest stage to known or potential problems.

Milestone reports are formally signed off by the supplier's project manager, normally by signing a signature page at the end of the document. The reports are accepted or rejected by the client organization, normally by the issue of a Project Memo confirming this – see below.

Project Memo System

All communications between the parties on technical and programme issues are sequentially numbered and sent to a single point of contact in each organization, who will:

- maintain a register of incoming and outgoing Project Memos

- distribute Project Memos to any internal addressees

- ensure that Project Memos are properly actioned

- make a monthly report of 'unclosed' Project Memos that are still open, that is, they have not been signed off by the project managers.

For incoming Project Memos the register records the sequential number of the memo and date received, the addressee and the subject. The equivalent register of outgoing Project Memos records the sequential number, the date sent, name of originator, name of addressee and the subject. If this is strictly adhered to there is no possibility of communications going astray or being forgotten. Where Project Memo numbers indicate that some previous memos are missing, these are immediately requested and an effort made to discover why they were received out of sequence.

Project Memos are particularly useful in complex projects where both the client and the supplier have several team members who need to interact with each other on technical issues. Simpler projects should use the same system as it represents good housekeeping and is good training for junior staff on project management techniques. Whether commercial correspondence should be included is a matter for each organization to decide but with this important caveat.

The Project Memo cannot under any circumstances alter the scope or cost of the project or the conditions of contract. For these to be altered the 'contract change' procedure, set out in the Conditions of Contract, must be adhered to.

An example Project Memo is given in Appendix 2.

Periodic Project Reviews

These face-to-face meetings involve a review of progress to date with particular reference to the technical specification. The following are included:

- Discussion on general progress

- Reports by the supplier's various team members, where the project is a cross-functional one or involves several people doing discrete work

- Discussion on problems and remedies

- Physical review of facilities and work done

- Budgetary review (except on fixed price contracts where this may be unnecessary)

- Agreed actions to remedy problems.

Whilst the project review can be used as a vehicle for deciding that the contract may be amended or varied, the review itself is not used as the method to enact such amendments. Both parties should be careful to use the important phrase of 'subject to contract' whilst discussing any tentatively agreed changes. The agreed action list should state that changes agreed to be relevant to the contract will not be valid until a contract amendment document is issued by the client.

Contract Close-Out

When the project has reached a successful conclusion, it will be necessary to formally close the contract and in so doing, signify that all outstanding liabilities have been satisfactorily discharged (except those, of course, which survive the contract – such as confidentiality). This will be the signal that final payments may be made and that all intellectual property rights, where appropriate, have been transferred. The client organization must be fully satisfied that:

- Contract deliverables have been received

- Both sides have fully discharged their various contractual liabilities

- All disputes are settled

- Documents and materials have been disposed of or returned to the client as set out in the contract

- Where a price variation formula was used to adjust contract costs, that final calculations under these have been made (there is sometimes a delay in waiting for the relevant indices to be published).

1 P. Sammons, The Outsourcing R&D Toolkit, Gower, 2000.