Chapter Five

Star Talent Creates Your Future

Today’s economy does not allow for mediocrity. If companies don’t have the best people delivering their products and services, their competition will. Peter Drucker pointed out decades ago that the ability to make good decisions regarding people represents one of the last reliable sources of competitive advantage because very few organizations excel in this arena. Now, more than ever, the single most important driver of organizational performance is talent—but not just any talent—stars. Only those organizations that comb the planet for the experts, prodigies, and geniuses can hope to lead their industries into the future. Average and ordinary simply won’t be enough—but neither will high potentials.

Understanding stars and virtuosity does not involve binary thinking—that is, one either is or is not a star. When compared to other high school players, by all objective criteria, we might consider an outstanding high school baseball player a great athlete. However, when contrasting him to college, minor league, or major league players, the evaluator might reach a different conclusion.

You have probably already spotted the “high potentials” in your organization. These people have shown consistently over time that they can be counted on to deliver results. Perhaps they even represent the best your company has ever employed. In other words, when playing in the league they’ve always been in, they set themselves apart from the average employee. You’re glad to have them, and you’d hire them again without hesitation. The question I ask my clients who have an aggressive growth strategy challenges some different thinking: “They got you here, but can they get you there?” In other words, their top performance exists on a continuum. They may be the best you’ve ever had, but do they represent the best your competition has ever had or will have? Here’s a way to think of this:

High Potentials |

Stars |

Ethical |

Beyond reproach |

Highly talented |

Expert |

Highly skilled |

Excellent |

Disciplined |

Enterprising |

Generally experienced |

Experienced in critical areas |

Maybe your high potentials are good enough to keep you in the game. And maybe not. Some of your high potentials may well have the potential to one day claim virtuoso status. They may have the raw talent, a commitment to excellence, and the resolve to develop both themselves and your organization. But you need to see evidence. You need to see proof that they can learn quickly and advance rapidly, both in terms of responsibility and skill acquisition. Only then can you be optimistic that you have the right people.

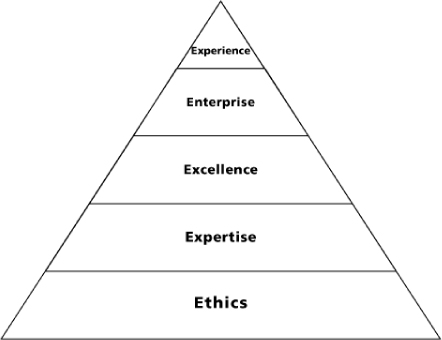

Stars distinguish themselves and exemplify the E5 Star Performer Model: Ethics, Expertise, Excellence, Enterprise, and Experience. They force people to take them seriously. They don’t raise the bar—they set it for everyone else. They serve as gold standards of what people should strive to be and attain. If you were to scour the world, you’d be hard-pressed to find people who do their jobs better. You wouldn’t hesitate to hire them again, and you’d be crushed if you found out they were leaving.

Because they are thought leaders, others look to these virtuosos for guidance and example. Often they consider them edgy and contrarian, but they seldom ignore them. Virtuosos chafe at too much supervision or tight controls—fortunately, they need neither. They constantly search for the new horizon and welcome the unforeseen challenge. No synonym for the word “virtuoso” exists. Some might substitute “artist,” “expert,” or “musician,” but these don’t suffice. Many can lay claim to these titles and still fail the virtuosity litmus test. By definition, few virtuosos exist. If you’re fortunate to have a team of them, recognize them for who they are, and use your influence to help them make beautiful organizational music.

Ethics: Doing Well by Doing Right

Even though some could claim that exceptionalism and virtuosity can exist independently of any moral compass, in business, ethics forms the foundation of both. Arguably, a great talent, such as Hemingway, can offer universal appeal for generations, even though many found him generally to disregard the rules of civility during his lifetime. Yet few would yank his widespread accepted title of literary virtuoso. Therein lies the imperfection of the metaphor. Business simply won’t countenance this sort of breakdown. Although somewhat abstract and ethereal, for the purpose of this discussion, let’s assume ethics underpins all that defines a true virtuoso.

Aristotle helped us understand this point of view more than 2,000 years ago. According to him, the chief good for man is happiness, which, according to his philosophy, consists of rational activity pursued in accordance with virtue. Therefore, living well demands doing something, not just being in a certain state or condition of integrity. It consists of those lifelong activities that actualize ethics and—as we now understand—create stars.

Aristotle insisted that ethics involves more than a theoretical discipline: we ask about the “good” for human beings, not simply because we want to have knowledge, but because we will be better able to achieve our good if we develop a fuller understanding of what it is to flourish. Aristotle maintained that the study of ethics should seek to influence behavior. Therefore, what do stars actually do to demonstrate their ethics?

In business, the difficult and controversial question arises when we ask whether certain goods are more desirable than others. For example, years ago I knew a consultant, Tim, who had the answer. Tim, who was based in St. Louis, routinely flew to New York to visit several clients. The agreement between Tim and these clients involved their paying his travel expenses. Therefore, Tim bought a roundtrip first-class ticket, per the agreement, and billed each of the three clients for it. He didn’t divide it among the three—he billed each separately for it and pocketed the difference. Legal? Probably. Ethical? No, but then I don’t recall anyone accusing Tim of either integrity or virtuosity.

Although Tim did what was good for him, ethics involves a search for the highest good, and Aristotle assumes that the highest good, whatever it turns out to be, has three characteristics:

1. The action is desirable for itself.

2. It is not desirable for the sake of some other good.

3. All other goods are desirable for its sake.

Obviously Tim’s decision to profit from the price of an airline ticket doesn’t pass Aristotle’s test. But it had other consequences.

Tim ran a boutique firm that employed other consultants who knew of his practices. Can anyone express surprise that they started emulating their boss’s behavior?

In addition to “massaging” his own expense reports, Tim took other shortcuts to drive the business. He routinely demanded the selling of services, even when that compromised the best interest of the client. He told clients what he thought they wanted to hear, even when what they needed to know differed. He required his direct reports to follow suit. Also, he frequently discussed highly confidential, guarded information with those who had no need to know.

The direct reports began to claim meals they could have eaten but didn’t, tips they should have given but didn’t, and expenses they might have incurred but hadn’t. Sometimes the firm passed these costs on to the clients, but eventually Tim learned he too had suffered from the unethical culture he had created.

Three other things happened. First, clients began to hear of the unethical practices, which caused him to lose business in the short run and suffer damage to the firm’s reputation in the long run. Second, Tim eventually found himself spending an inordinate amount of time policing the behavior of his direct reports. Instead of building a business, he squandered his time reviewing expense reports and monitoring the elevators at 4:30 to make sure no one left early. Third, Tim lost the stars he had hired. He had a stable of thoroughbred stars that left him one by one through the years, simply because they wanted better for themselves and the clients they served. They wanted to work in a place that deontologically matched their personal commitment to doing the right thing.

Deontology, from the Greek deon, which means “obligation” or “duty,” is the ethical position that judges the morality of an action based on the action’s adherence to rules—choices that are required, forbidden, or permitted. This school of thought posits that some acts are inherently ethical or unethical, irrespective of legality, pragmatics, or common practice. For example, some people consider torture wrong, regardless of the legality of it or its use to obtain critical intelligence. These people support a deontological view. Others consider torture generally wrong but, when not taken to extremes, necessary for national security. Philosophers commonly contrast deontological ethics with consequentialist ethics—that is, the rightness of an action is determined by its consequences.

Stars embrace the deontological school and evidence this in their behavior. You don’t have to check their expense reports, because even if they could get away with padding it, they wouldn’t. You don’t have to worry about them embarrassing the company with inappropriate behavior in their personal lives, because they self-regulate. They don’t believe that two wrongs ever make a right, and they don’t look for the moral loopholes because they wouldn’t jump through them anyway. Perhaps Bernie Madoff could have ranked among the financial stars of the world had he used his innate talent differently and embraced this school of ethical theory.

As Aristotle noted thousands of years ago, opinions vary about what benefits human beings. Many excuse behaviors that would ordinarily seem wrong, but when done for the betterment of the organization, can be forgiven. (One might note that Aristotle never had a sales quota.) Similarly, legal loopholes allow for wrong-minded logic. Philosophers since Aristotle have tried to explain ethics in more practical terms, but I embrace the three criteria he posited.

Integrity is a not a raincoat you put on when the business climate indicates you should. It is a condition that guides your life—not just a set of protocols. Stars don’t acquire their ethical foundations solely by learning general rules. They also develop them—those deliberative, emotional, and social skills that enable them to put their understanding of integrity into practice in ways that are suitable—through practice. Similarly, stars understand that they can’t “teach” ethics to others by requiring their signatures on a statement. Instead, they exemplify and model ethics in their personal and professional lives.

At a visceral level, stars understand Hemingway’s observation that “What is moral is what you feel good after. What is immoral is what you feel bad after.” (His life indicates he understood this intellectually, as many of us do, but failed to weave this knowledge into his day-to-day behavior, a tendency we also share.) Going beyond awareness actually to practice integrity is one of the things that separates the virtuoso from other top performers.

Expertise: The Raw Data of Talent

Some might argue that ethics should not be included in a discussion of virtuosity. As mentioned previously, we often consider people world-class, with no regard to conduct outside the arena of their excellence. However, no one would suggest compromising on expertise, because it literally defines what lies at the heart of virtuosity. To better understand the nature of expertise, I offer four critical constructs: intelligence, talent, knowledge, and consistency of performance, which also transitions us to a discussion of excellence. (Experience should be considered a fifth construct, but in this discussion, I will address it separately.)

Although the ranking of these five might differ, depending on the nature of the virtuoso, in business, the most crucial forecaster of executive success is brainpower, or the specific cognitive abilities that equip us to make decisions and solve problems. Three main components define this leadership intelligence: critical thinking, learning ability, and quantitative abilities. Of these, critical thinking is the most important and the least understood.

Dispassionate scrutiny, strategic focus, and analytical reasoning form the foundation of critical thinking. These abilities equip a person to anticipate future consequences, to get to the core of complicated issues, and to zero in on the essential few while putting aside the trivial many. As I pointed out in Landing in the Executive Chair: How to Excel in the Hotseat, you can often evaluate a person’s critical thinking based on their pattern of decision-making:

• Does this person understand how to separate strategy from tactics, the “what” from the “how”?

• Can this person keep a global perspective? Or does she or he become mired in the details and tactics? “Analysis paralysis” has caused more than one otherwise top performer to allow opportunity to slip away.

• Do obstacles stop this person? Or do they represent challenges, not threats? The ability to bounce back from setbacks and disappointments frequently separates the strong strategist from the effective tactician.

• Can he or she create order during chaos? Stars keep problems in perspective and realize that very few things are truly as dire as they first seem.

• Does this person have the ability to see patterns, make logical connections, resolve contradictions, and anticipate consequences? Or is she or he unaware of trends?

• What success has this person had with multitasking? Often the ability to handle a number of things at once implies good prioritizing and flexibility.

• Can this person think on his or her feet? Or does this person miss opportunities because of an inability to respond? Quickness, however, does not guarantee effective critical thinking skills. Some people rush to make mistakes; others take their time and then err.

• Can this person prioritize seemingly conflicting goals? Is this person able to zero in on the critical few and put aside the trivial many when allocating time and resources?

• When facing a complicated or unfamiliar problem, can this individual get to the core of the issue and immediately begin to formulate possible solutions?

• Is this person future-oriented and able to paint credible pictures of possibilities and likelihoods? The key question remains, “Can this person solve complicated, unfamiliar problems?”

• How do unexpected and unpleasant changes affect this person’s performance? If his or her analytical reasoning is well-honed, organized, systematic decision-makers can respond favorably to change, even if they don’t like to.

• When in a position of leadership, does this person serve as a source of advice and wisdom? Can she or he act as an effective sounding board to others who struggle with complex issues?

Most people can learn to follow a protocol or set of procedures. Give them a check list, and they can execute the plan. They know how to run fast, but sometimes they don’t know which race to get in. Often these individuals are valuable employees, maybe even top performers. But they aren’t stars.

General learning ability is the second most important aspect of leadership intelligence. When leaders can acquire new information quickly, they do not lose valuable time moving through the pipeline. They size up the new leadership situation, learn about their people, learn about products and processes, and then immediately act on this knowledge. When this happens, the organization responds by moving the new leader’s idea to action. Reading ability, vocabulary, and fundamental math skills form the foundation of learning ability. Often, but not always, educational success is an accurate predictor of how quickly someone will learn in the organization. Certainly, ongoing learning teaches people about their own learning styles, so they become more proficient at acquiring new information and skills.

Although critical to success at the top levels of most organizations, not every turn in the leadership pipeline requires quantitative abilities. Knowing what the numbers mean and using them to make sophisticated business decisions equips an individual to make budget or profit and loss assessments. Superior development of these skills allows a person to evaluate the nuances of mergers, acquisitions, and risk-taking ventures as they analyze strategy. Numerical problem-solving, critical thinking, and proficient learning define the basics of business acumen.

In my more than 35 years of consulting, I have found that, without question, natural intelligence is the most important component of expertise in the business arena and the single most significant differentiator at the upper echelons of large organizations. Stanford psychologist Lewis Terman recognized this when he pioneered his IQ tests in the early 1900s. In his opinion, nothing about an individual is as important as IQ, except possibly morals.1 I echo the observation and sentiment, but I also recognize the observations of “IQ fundamentalist” Arthur Jensen, who observed that IQ levels, beyond those that would qualify an individual for admission to graduate school (about IQ 115), become relatively unimportant in terms of success. In other words, IQ differences in the upper part of the scale—above 115—have fewer implications than the thresholds below that.2

To give a frame of reference, most successful professional football players are big guys, but beyond a certain weight, you don’t see increased skill or excellence. Like the size of NFL players, intelligence has a threshold. You have to be smart enough to do the job well—but not appreciably smarter than that. Stars don’t lack leadership intelligence; they have enough. But they also embody what psychologists call “practical intelligence” or “emotional intelligence.” They know what to say, when, and to whom. They understand their own emotions, fears, and motivations and those of others.

In a general discussion of virtuosity, talent and intelligence would be separate. Some individuals may have exceptional talent for music, art, acting, or some other activity but not exceptionally high IQs. However, once again, in the business arena, the most sought-after talent will usually be so closely linked to cognitive abilities that separating them seems impossible. But there are exceptions. I have tested world-class salespeople who earned modest scores on all the cognitive assessments. They didn’t even score well on the sales knowledge tests! But put them in front of a customer, and they sell. Therefore, when asked to assess a salesperson, I tell clients the one and only reliable piece of data is track record. Do they have a talent for selling? If they do, little else matters. If they don’t, nothing else matters.

Excellence: Consistency of Performance

Although required, expertise is not enough. Even when people possess world-class talent, they must practice and hone their skills routinely and religiously. For example, renowned pianist-turned-conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy said that if he misses a day of practice, he notices. If he misses two, his wife notices. If he misses three, the audience notices. Ashkenazy, like most stars, realizes the unmistakable link between practice and excellence.

Of the five constructs of star performance, excellence poses the most challenges for understanding it and attaining it. What makes us excellent?

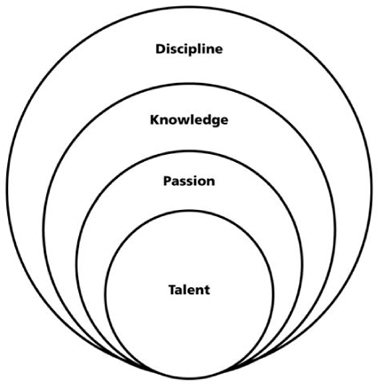

Talent stands firmly at the foundation of excellence, but awareness of the talent has to occur, too. Unknown potential does us little good if we leave it in the realm of the unidentified. That’s why exploration of a variety of activities and subject matter is so important for children. They may possess enormous reserves of untapped talent that lie dormant for a lifetime. That doesn’t happen to the stars that shine on our stages and in our organizations. Through whatever process and help from others, they identify the strengths that set them apart.

It all starts with talent—the natural ability or aptitude to do something well. People who possess talent often initially take it for granted, even asking themselves, “Can’t everyone do this?” Eventually they realize they can deliver consistent stellar performance every time they attempt the activity, and not everyone else can. Further, once they have identified the strength, they don’t abandon it. Instead, their passion spurs them to find ways to use it in ever-evolving new ways.

Passion serves as a kind of magnetic field around the activity or pursuit. Stars feel themselves pulled to learn about and participate in things related to their talents, while they simultaneously feel repulsion for some that aren’t. For example, a linguist might have looked forward to English class but dreaded science. He might have found the study of literature fulfilling but the study of botany burdensome. Stars literally crave the thing for which they feel passion. Sometimes this hunger to know about a subject will unveil a talent early in one’s life, but sometimes the talent surfaces later—along with the zeal to develop it.

After they recognize their talent, they acquire knowledge—the content and context for using it. They learn, either by themselves or from others, what they need to know to grow their innate abilities. A would-be virtuoso may have the inborn talent of perfect pitch, but unless and until someone shows her how to hold a cello, she will never gain the knowledge and skills that will make her the world-class cellist she dreams of becoming. Even though it all involves hard work, stars acquire new skills quickly and adeptly because the process usually feels painless and enjoyable—which circles back to fueling the passion they feel for their talents.

Then, they organize their lives so they can apply their excellence—they hone the skills and practice what they’re already good at. They develop the discipline to practice, but they realize practice only makes perfect if you practice perfectly, and no amount of practice will help the person who lacks talent.

Athletes know this, but those of us in business often overlook it. Sports greats work with coaches every day who watch them, videotape them, give them feedback, and constantly strive to improve on already nearly perfect performance. Also, athletic coaches don’t waste their time attempting to develop talent where it doesn’t exist. Instead, they concentrate their coaching efforts on those who have exhibited the raw ability to become excellent. And it all happens with a disciplined approach to practice that allows the athlete to attain virtuoso status before the age of 30.

Some would-be greats have the talent, passion, and knowledge to attain virtuoso status but fall short because they lack discipline, which means they lack an ordered approach to developing their talent. Maybe they simply don’t know what they would have to do to improve. Perhaps they don’t have a teacher or mentor who could shine the light into the darkness to illuminate the path they will need to take to reach their goal of greatness.

But that usually doesn’t explain the breakdown. Most people understand what they need to do to change and improve, but they lack the resolve to do it. They don’t develop the habits that would ensure their continued advancement because that would cause a disruption to their current lives. The rewards of virtuosity lie in the future, but the disruption and sacrifices happen today.

Tempting though it may be, we should not confuse excellence with perfection. Achieving excellence certainly demands a disciplined approach to development of talent and passion and the ability to deliver a stellar performance most of the time, but it does not require perfection: accuracy, precision, exactness, and care, yes—but not perfection. If a virtuoso defines perfection as the goal, three things happen. First, the person never achieves the goal because it’s unrealistic. Second, along the path to perfection, the star performer can lose motivation, and frustration will set in. And finally, the star will lose valuable time and squander precious resources trying to accomplish something that won’t appreciably augment his or her efforts. Star athletes learn these lessons quickly.

In a June 2, 2010, American League baseball game in Detroit, Detroit Tigers pitcher Armando Galarraga nearly became the 21st pitcher in Major League history to pitch a perfect game. Facing the Cleveland Indians, Galarraga retired the first 26 batters he faced, but his bid for a perfect game vanished when first-base umpire Jim Joyce incorrectly ruled that Indians batter Jason Donald reached first base safely on a ground ball. Galarraga finished with a one-hit shutout in a 3–0 victory. The following week decision-makers in the world of baseball opted to deny pitcher Galarraga his “perfect game,” even though the video confirmed the out, and umpire Jim Joyce admitted his bad call on what should have been the final out of the game.

Unlike others who might have been in his situation, Galarraga accepted the injustice with poise and got the next batter out. Joyce personally apologized for his mistake, and the Detroit fans gave the umpire a standing ovation the next day. Also, in a show of good sportsmanship, Galarraga shook hands with Joyce.

Galarraga, by all objective criteria, had been perfect; conversely, Joyce had been flawed. Both men, however, showed a laudable level of good sportsmanship in the face of adversity. Probably neither man thought that game his finest hour—Galarraga because of the profound injustice of losing a much-coveted distinction, and Joyce because of his own limitations—but both gave the rest of us a lesson in the importance of stellar sportsmanship, and both illustrated that our goal should be success, not perfection.

If we make perfection the goal, we will never experience triumph, and we’ll seldom be satisfied. Stars thrive on achievement and accomplishment because both bring satisfaction. Through my coaching experience with would-be perfectionists, however, I’ve learned this: They think they’re right. “What could possibly be wrong” they ask me, “with making things precise and demanding accuracy?”

Good question. The major problem with perfection is loss of time. It simply takes too long to make things perfect. You can quickly become mired in the details and suffer analysis paralysis.

For example, I once worked with a top performer named Cheryl, a card-carrying perfectionist. She did outstanding work, but she never met a deadline that I’m aware of. Flawless and exacting, her reports reflected the enormous amount of time she had spent writing each as though it would vie for the next coveted spot on the New York Times bestseller list. She wrote and rewrote. She edited. On business trips she called her assistant to change a “happy” to a “glad.” She spent an inordinate amount of time trying to make each report a work of art that everyone would admire for decades to come. (A handful of people read these reports before filing them away, never to be read again.)

I suggest she was not a star because she overlooked opportunities to build the business through accomplishing more work. And she annoyed clients when she didn’t meet the deadlines. Also interesting, her office resembled the aftermath of Three Mile Island. Instead of nuclear waste, however, she covered every surface with papers, files, and assorted debris. (Apparently perfectionism does not have universal demands.)

The goal of stars and those who lead them, therefore, needs to be success, not perfection. If you try to make everything perfect, you sacrifice results and efficiency. Brain surgery and launching the shuttle demand nearly perfect performance every time. For most of us, however, 80-percent right is good enough. The time and missed opportunity you’ll invest to get the other 20 percent won’t usually give you a strong return on your investment. Stars understand that “finished” trumps “perfect” most of the time, so they move into the future more quickly than others.

Stars have what I call a “future tense” lens. They see benefits in the future, so they eschew instant gratification for the sake of the long-term, enduring pleasure their talent promises. They have reason to believe they will be great, so they don’t settle for reasonably good performance—but neither do they insist on perfection. Because their progress has been constant and predictable, they develop optimism that fuels their discipline. When they do face a setback, they have the resilience to bounce back and recommit to their systematic, disciplined approach to excellence. Their disciplined approach to developing their excellence also marks them as those who are enterprising and resourceful.

Enterprise: Setting the Bar

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell introduced “the 10,000-Hour Rule” which he formulated after studying the work of Anders Ericsson. Ericsson followed the lives of professional musicians and contrasted them to those non-professionals who had started playing an instrument at the same age. The research showed that the professionals steadily increased their practice time every year until, by the age of 20, they had reached 10,000 hours. No “natural” musicians floated to the top with less practice.

Is the “10,000 rule” a general imperative for success? Will we find stars of every stripe proving it? Generally speaking, yes. Those whom we would consider stars in business have usually worked in their area of expertise at least five years. If these people worked a 40-hour work week 50 weeks a year, they would have “practiced” approximately 2,000 hours a year, thus supporting the rule.3

If you work hard, you will succeed at some level. If you don’t, you won’t. In my thousands of hours of coaching, I have found that hard work and integrity account for success in many industries all the way up the ladder—until you reach the top rung. At that top rung, the hard work has to remain steady, but then talent and expertise start to play a bigger role. Innate talent leads to excellence, but as Gladwell pointed out with his 10,000-Hour Rule, excellence doesn’t happen without dogged determination.

As I’ve repeatedly noted, leadership intelligence accounts for success at the upper echelons of any organization, but no one succeeds without a strong achievement drive. Certainly the talent to zero in on best uses of time helps prioritize what needs to be done and the critical nature of some tasks, but without a clear bias for action, movement through the pipeline cannot occur.

The willingness to work hard and a high-energy, go-getter attitude define “enterprising.” A competitive spirit, a “can do” attitude, self-discipline, reliability, and focus further augment it. Personality assessments can help identify achievement drive in new hires and internal high-potentials, but observation provides the surest way to know if a person has what it takes to get the job done.

Largely because of their passion to apply their talent and expertise, stars eagerly embrace challenges and overcome obstacles. Their motivation clearly starts at their core and doesn’t respond well to external things like pep talks, incentive programs, and charisma. Resourceful and determined, stars invent rather than respond to the environment around them. They want to do their best work, so they don’t readily take “no” as any kind of answer. By experimenting with novel approaches and eagerly embracing innovation, they develop the experience to understand what kinds of efforts will engender the most dramatic growth and change.

Experience: The Yesterdays That Define the Tomorrows

When I advise clients on hiring and promotion decisions, a recurring challenge I face involves helping them evaluate experience. Most senior leaders tend to over-value it, especially when the person has “just what we need” in terms of previous employment and industry experience.

By my definition, stars offer enough experience to claim expertise and to succeed, but when I encounter true virtuosity, I think of experience differently. I don’t want to see a resume that chronicles 15 years of experience, when 10 of those years really amounted to one year 10 times. Similarly, a long list of jobs that showed no advancement in skills and leadership doesn’t impress me.

On the other hand, Captain Sullenberger rose to fame when he successfully landed U.S. Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson River on January 15, 2009, saving the lives of 155 people. In 2009, Sullenberger was a senior captain with more than 19,000 hours of flying time that he had accumulated in his more than 30 years of flying experience. In interviews and writings after the crash, Sullenberger credited his vast experience in both flying and safety for his ability to do what had to be done on that January day. Could he have done it with 2,000 hours of flying time? We’ll never know. If you were to put a group of military and commercial pilots in a room and ask them this question, two things would happen: First, you’d have a fierce debate on your hands. Second, you still wouldn’t have a definitive answer. The disagreement doesn’t address whether or not stars need experience. The question remains: “How much is enough?”

Stars bore easily, so they move quickly through the ranks and separate themselves from other high potentials with their sheer hunger for knowledge, opportunity, and challenge. They also demonstrate self-awareness, which is a key construct of experience. They accept their talents and weaknesses with equal degrees of equanimity. They know they can’t excel at everything, so they isolate those talents that will define their success and concentrate on situations that will allow them to flourish.

Consider John. In 2005, a member of the board of directors of a St. Louis publicly traded, $1.5 billion company called me to help them in their selection of a new CEO. They had narrowed the field to two candidates: Dan and John. Of the two candidates, Dan offered more impressive experience, but in a more general sense, he was the weaker candidate. I told the search committee that John was the better of the two candidates, even though he didn’t offer the experience Dan did. I went one step further and said that if John didn’t accept their offer, they’d have to re-open the search because, although experienced, Dan didn’t have the leadership skills to run this company. They kept telling me more about Dan’s experience. I finally said, “Guys, here’s what I know about experience. Age does not always bring wisdom. Sometimes age comes alone.” In Dan’s case, that’s what had happened. Reluctantly, the board hired John, and a competitor hired Dan and summarily fired him six months later.

When John took the helm in November of 2005, the stock sold for $19. Almost overnight it doubled and then quickly tripled. In a little more than three years, the company had expanded in North America, Europe, and Asia.

John succeeded for several reasons: He had 16 years of different experience, not one year 16 times; he’s a brilliant strategist; he’s self-aware, ethical, enterprising and excellent—in short, a virtuoso. Experience plays a major role in defining virtuosity, but it appears at the top of the pyramid for a reason. To identify stars in your chain of command, weigh the other criteria more heavily, and don’t exaggerate the role of experience. Realize its major function is to help you recognize a mistake when you make it again, and ideally, to make fewer of the ones you’ve made before.

Conclusion

We seem to understand, at least intellectually, that we will excel only by leveraging strengths, not by mitigating weaknesses. Of course, we should try to minimize weaknesses, but only to the point that they no longer undermine our strengths. In other words, working on a weakness will help us prevent failures, but it won’t ensure virtuosity.

This commitment to leveraging strengths won’t happen automatically, however, because our understanding of the concepts tends to be more intellectual than applicable. Too frequently we focus on pathology and weakness, not health and forte. For instance, psychologist Martin Seligman found more than 40,000 studies on depression but only 40 on joy, happiness, or fulfillment. Fear, depression, and anxiety can mask talent and retard the development of excellence, but overcoming them won’t create it.4 To understand and attain virtuosity, we need to spotlight those things that cause it, not the ones that stand in its way. Only then will we be able to develop it—in ourselves, in those who count on us, and in our organizations.