Chapter 3

Setting Up Shop (II)

Finding the Money and Choosing the Right Chinese Business Partner(s)

“Forming a business partnership [in China] can sometimes go really wrong. I think everybody entering a business partnership should be very cautious. This doesn’t apply only to Chinese people; people everywhere are complicated. People are quite greedy. When money is involved, it can be very difficult.”

Mark Pummell (UK), Founder and CEO, ChinArt, Sinapse, and Music Pavillion

“When it comes to business plans, you have to make sure you are profitable within a year. It is nonsense to make a five-year plan before you can make a profit. Things are changing so fast [in China] that if your business model isn’t profitable in a year, you have to seriously reconsider. Maybe that’s not true in other places, but it is true in China.”

Olaf Litjens (Netherlands), Founder and CEO, Unisono Fieldmarketing (Shanghai)

Introduction

This chapter covers the second set of “initial steps” for foreign businesspeople setting up shop in China: funding the new business, and finding the right Chinese business partners. Both steps are difficult for entrepreneurs in any business environment worldwide, but starting up in China offers several unique additional challenges.

In terms of startup funding, entrepreneurs in China generally choose one of three main sources of funding: their own savings; those of family or friends; or funds provided by professional investors. Unlike in developed markets, it is virtually impossible to obtain financial assistance from China-based banks. The first part of this chapter examines how our 40 entrepreneurs successfully secured startup money without bank assistance.

The chapter then covers the crucial issue of choosing the right business partner if the foreign party opts not to go it alone.

We have divided the lessons shared in Chapter 3 into two main topics:

Finding the Money

Entrepreneurs worldwide struggle to secure the funding necessary to get started and build their business. But for foreign startups in China, the options available are fewer and the financial bumps along the road can be more treacherous.

First, it is nearly impossible to obtain bank financing in China, as the nation’s immature banking industry doesn’t include channels for foreign entrepreneurs seeking seed money. A 24-year China veteran and founder of several companies, including his current fieldmarketing venture, Olaf Litjens explains the dilemma most foreign entrepreneurs face: “You can’t get a loan from a local bank, because Chinese banks won’t fund a foreign entrepreneur—and a foreign bank won’t do it because you are small and China is still a very complicated country. So, it’s extremely hard to get financing.” His own solution has been to collect funding from partners, clients, or suppliers: “We always get money from other people. We are very good at this!”

![]() Chinese banks are generally reluctant to loan to private enterprises. Consider using clients and suppliers as your funding source.

Chinese banks are generally reluctant to loan to private enterprises. Consider using clients and suppliers as your funding source.

Fellow Dutch entrepreneur Nic Pannekeet echoes Litjens’ sentiments: “I used my own money [to start CHC Business Development]. I don’t know of any local bank that would be willing to offer me funds.” In fact, he explains, even some of China’s most successful business ventures have been refused bank funding. A case in point is Shanghai’s Xintiandi neighborhood, where historic pre-communist buildings have been architect-restored to create a very trendy and commercially successful shopping–dining–entertainment district. Says Pannekeet: “I know the guy who developed Xintiandi and his real estate company. When he was planning the project, the bank said that the idea was good but it would be very hard to make money, so they couldn’t lend to him. But now, you see how Xintiandi has developed.” His point: if the developer of Xintiandi couldn’t convince the banks to extend him a loan, most foreign investors should also expect to be denied financing. Pannekeet himself says that the only time he was granted a bank loan was in the southern Chinese city of Kunming. But in that case, he turned down the offer. “In Kunming, I had to pay a commission under the table to the bank official to get a loan. So, I gave it up.”

![]() Save enough money to survive at least during the first months of operation. Self-finance is the safest option for funding your business.

Save enough money to survive at least during the first months of operation. Self-finance is the safest option for funding your business.

Lacking bank loans, all of our business pioneers had to use alternative means to acquire startup funds. The most obvious strategy, they agree, for those with either the time or the financial means, is simply to wait until you have enough funds to launch on your own. South African consultant Kobus van der Wath, who launched The Beijing Axis, voices a typical mindset: “My firm is self-funded. I started with my own savings. [In the initial stage,] I was approached by a few people wanting to invest in the company and buy equity, and therefore, take some level of control. I immediately saw that none of the people or entities understood my business. I didn’t want to have a board that didn’t instinctively understand the business.” So, Van der Wath waited until he could fund the business himself, and then in 2002 began registering entities in Hong Kong, Mainland China, and South Africa.

Home decorating manufacturer Wendy Tai has used a conservative policy to fund her China-based business after moving operations from her native Taiwan to mainland China 20 years ago. “Our business has grown with our own money, without the help of investors. The usual model is 30% self-finance, 70% borrowed from the bank. We only have self-finance,” she says. Even when friends suggested channels for obtaining bank loans, Tai refused. “Many of our friends have suggested that we borrow money from the bank to grow faster. However, we insist on our way to develop our business. Now, when we look back and compare with the company in the old days, we’re amazed by its rapid development.”

Austerity is also the rule of thumb for British counseling and arts entrepreneur Mark Pummell. “It’s very important to me that I never borrow money from anybody. Every penny [of our startup fees] came from us. If somebody pays 50% of your business here, they own 50% of your business—you don’t have full control.” In order to stick to the principle of not borrowing money, he started his China-based businesses with £100,000 of personal savings. Although the aim was to open several businesses eventually, his strategy was to begin with a small-scale niche venture that had the potential to be profitable. Pummell, who is a licensed psychotherapist in the United Kingdom, explains: “Therapy was my first business. Very quickly [after arriving in China], I saw the opportunity that nobody was providing psychotherapy [for expatriates]—literally nobody. A few people approached me and suggested that I start my practice.” So, he rented a small office above a candy factory in Shanghai. “Each month, I kept my overhead very low. I just required some furniture, a few chairs, couches, and business cards. I placed some ads in [a free Englishlanguage weekly magazine for expatriates]. Then my phone started to ring and never stopped ringing.”

After his first business became stable and steady, Pummell launched an art gallery/tea shop, and then a recording studio, and musical instrument export business for professional musicians. As the businesses grow, he has stuck to a principle of controlling costs. “I think the number one thing is to keep your overhead low. It’s a temptation to spend money, particularly in Shanghai.”

Irish national Ken Carroll and his business partner followed a similar plan of using their own funds to launch Kai En English Training Center, a chain of English-language schools, in China. “My partner and I had just US$200,000 between us. We got on a plane and came to Shanghai. We didn’t know anyone, but we were committed to it. It was actually quite silly.” Carroll followed a strategy of keeping costs very low and initially launching a safe, stable business. (The partners had managed a similar chain of English-language schools in Taiwan.) “We went without a salary for 15 months, which wasn’t very nice,” Carroll remembers. Still, the strategy worked. Kai En eventually grew to a five-school chain in Shanghai, providing a steady and stable income source. “It’s not like a billion-dollar corporation but it’s profitable—nice and solid,” Carroll says. Today, he uses income from Kai En for his own salary and to help fund the growth of his new venture, Praxis, which offers web-based language-teaching services, including ChinesePod, SpanishPod, and ItalianPod.

One of our China business pioneers sums up the potential risks incurred with a self-funded venture. After five years of operation, he faced a dispute with his Chinese business partner that threatened to wipe out much of the earnings he had accumulated so far. He explains: “When I first developed my company, I used some of my own money and used a lot of my time. I also didn’t pay myself a salary, just a stipend to survive on each month, for the last five years.” The risk for him is that, in 2008, he ended his partnership with the Chinese partner and reopened on his own. “The hardest thing for me is that, if the [new] business fails, I will have wasted all the effort and struggle of the past five years.”

Finding Investors

Not every entrepreneur has US$200,000—or more—in personal savings available to use in launching their China-based business. Below are strategies from business pioneers who had to borrow funding, mainly what some entrepreneur literature calls the “three Fs”: friends, family, and fools.

“We didn’t want to seek venture capital because the earlier you get investors involved, the more you have to give to them.”

Aviel Zilber (Israel), Chairman, Sheng Enterprises

In launching Sheng Enterprises in Shanghai in 2003, brothers Aviel and Jordan Zilber used their own funding plus “angel investors” from their native Israel—mainly their uncle and a small group of friends and acquaintances. Aviel explains: “We didn’t want to seek venture capital because the earlier you get the investors involved, the more you have to give to them.” However, as Jordan explains, even the strategy of borrowing from family and friends has drawbacks: “When I was looking for money, I was anxious to realize my dream. But now, looking back, I realize I gave away shares too cheaply.”

When launching Emerge Logistics Shanghai, China veteran Jeffrey Bernstein also chose to target offshore clients as potential investors; he believed international customers would be most likely to understand the value proposition for his services. While this strategy is safer in terms of a stable payment stream once sales are finalized, it does require facing the initial difficulty of attracting customers located around the globe while being based in China. “One big challenge has been starting from Day 1 as a global company—meaning the operations are exclusively in China, but the client base is exclusively from overseas,” says Bernstein. The geographical distance between the service and the customer creates “a resource and logistical challenge” that goes beyond the usual startup difficulties, he continues. “In most entrepreneurial companies the founder wears many hats, but one person can only be in one place at a time. The challenge is how you handle a global startup when you really need people on both sides of the globe.”

In terms of the specific challenges he faced in launching Emerge Logistics as an FIE, Bernstein explains that he first had to raise capital of US$200,000. He had planned to use his own savings, plus funding from outside investors. But attracting investors was difficult without proven operations: “One main challenge is in finding external capital. There is the chicken-and-egg phenomenon—before the business starts and you have serious operating costs, that’s the time to go on a road show [to attract investment],” he says. “But at that time, the business is just a concept, and it’s very difficult to get investors to sign up.”

Bernstein found himself in the difficult position of talking to investors while readying to launch. In the end, this plan worked: “We delayed as much as possible until we had ramped up, and then a high-school friend gave me the remaining capital at the last second, and the rest was history,” he says.

“One main challenge is in finding external capital. There is the chicken-and-egg phenomenon— before the business starts ... that’s the time to go on a road show [to attract investment]. But at that time, the business is just a concept, and it’s very difficult to get investors to sign up.”

Jeffrey Bernstein (USA), Founder and Managing Director, Emerge Logistics Shanghai

Attracting Venture Capital

Consultants and interviewees stressed that there is plenty of venture capital coming into China, but that small-scale startups are at a disadvantage in attracting it. Says American consulting company founder Steven Ganster: “There’s a lot of [VC] money out there. There’s a lot more money than there are projects [in China], and there are many funds that are China-specific. If you have a good value proposition, there is a growing pool of venture capitalists who have [both] money and a fascination with China.” Ironically, the trouble for startups, Ganster says, is that it is often harder to get a limited amount of seed money for a small-scale venture than it is to attract larger amounts for a bigger project. “Funding of less than US$1 million—that’s hard money to get.” He adds that when your business is running successfully, “money is easy to find.”

But some of our interviewees did attract outside investors, simply on the strength of their business plan. Turkish businessman Onder Oztunali received funding from a Hong Kong investor for whom he had worked on projects in Turkey and Thailand. “That first investment is very difficult to get because you need people who believe in you and believe in your capabilities,” says Oztunali. “My investor is a really smart guy; he immediately saw the fundamentals of my business.” After receiving financial support, Globe Stone Studio eventually opened entities in Turkey, Hong Kong, and mainland China.

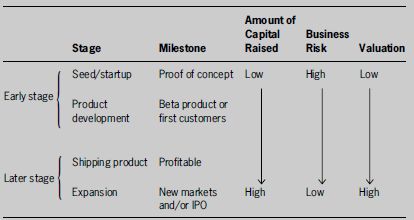

TABLE 3.1 Characteristics of Companies by Stage

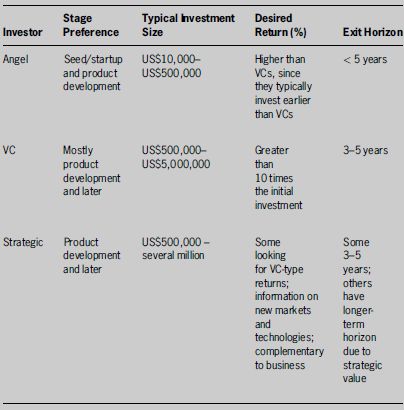

TABLE 3.2 Types and Characteristics of Early-stage Investors

Marc van der Chijs, founder of the online video downloading website Tudou (similar to U.S.-based YouTube) and other i-businesses, started his first venture with his own funds, then attracted several VCs. “It’s not difficult to find VCs, as they’re all looking for opportunities. But it took almost a year for the evaluation.” Today, Van der Chijs enjoys excellent relations with his investors. “[Our relationship with them] is very good, because we have met all our business targets so far. We’re really close, and we go out for drinks. It might be very different from the VCs you work with in other companies. Most of them are Chinese VCs, and some are U.S. VCs. We have in total seven to eight VCs. Some of them are on the board of directors, depending on how much money they’ve invested.” Van der Chijs finds the contribution of VCs very positive. “They really helped us to grow and are really successful. I think Tudou was very lucky with its VCs. We chose the right ones, and they have helped us tremendously over the past several years.” Today, Van der Chijs is in the enviable position of being able to choose from among willing investors: “Now, we are very successful, so we can choose which company to work with—just like a beauty contest.”

“If you have a good value proposition, there is a growing pool of venture capitalists who have [both] money and a fascination with China”

Steven Ganster (USA), Founder and Managing Director, Technomic Asia

As a final word of advice on financing, many of our interviewees stressed the need—after receiving initial funding—to keep costs low and to quickly establish a positive cash flow. Dutch businessman Olaf Litjens gives this advice to incoming foreign entrepreneurs to China: “People always tell you to ‘think long-term’ in China. But I say: ‘When it comes to business plans, you have to make sure you are profitable within a year.’ It is nonsense to make a five-year plan before you can make a profit. Things are changing so fast here that if your business model isn’t profitable in a year, you have to seriously reconsider. Maybe that’s not true in other places, but it is true in China. If you are an entrepreneur with a relatively small business, you have to make sure you are profitable in a year, or you have to seriously consider whether you are in the right business.” It seems that, in China, the following financial principle holds true even more strongly than elsewhere: profits are the food of the business, while cash flow is the oxygen. You can live without food for some days, but for only minutes without oxygen.

![]() Keep your initial costs low, and try to establish a positive cash flow as quickly as possible.

Keep your initial costs low, and try to establish a positive cash flow as quickly as possible.

Choosing the Right Chinese Business Partner(s)

Few China entrepreneurs launch a business venture entirely on their own; for practical and professional reasons, many of the 40 business founders/owners we interviewed launched their China venture with at least one partner. Finding the right partner is another critical decision in the birth of any new company. In this chapter, we share lessons learned in choosing a Chinese business partner. (For advice on working with a fellow non-Chinese as your business partner, see “Problems With Foreign Partners” in Chapter 2.)

In practical terms, using a Chinese–non-Chinese partnership is a logical blend; the domestic partner handles domestic issues such as government relations, distribution, and insight into domestic clients or customers; while the foreign partner provides technology or expertise in home-country standards, as well as managing foreign regulators, suppliers, or buyers.

Unfortunately, many of our interviewees working with Chinese partners have had some negative experiences. One such case is described here by U.S. entrepreneur Bruce Robertson, founder of Asia Pacific Real Estate. Under their partnership agreement, the Chinese partner was to handle government issues, while the foreign side would handle on-site issues. Problems arose when the Western side became suspicious of the way the Chinese partner managed the use of utilities for the venture. “We got the impression that the cost we were paying for utilities used on-site was way above what it should have been,” says Robertson. “We were never able to prove this, but we thought the Chinese developer was getting a discount on the outside cost and that we were paying a premium because the same utility company was doing both the off-site and on-site utility distributions. We intervened and negotiated the right to take over the cost and the administration of the off-site part. After that, our on-site distribution costs went way down. From our experience, I would say that it pays to conduct your own negotiations with the Chinese authorities, rather than leave such matters entirely in the hands of your Chinese partner.”

China hand Olaf Litjens shares another battle tale: “When we operated an export business [in the mid-1980s], we had four shareholders—my current partner Martin, a Chinese guy, a guy in Holland and myself. The Chinese guy was in charge of purchasing and quality control. The business was very successful—from year one, it was profitable—and we each took 25%. The thinking of the Chinese partner was, ‘Great, it is working and we are all making good money. If I had the business alone, I would have made four times more money. I am missing out on three-fourths of the profit.”‘ In year two, before the next buying season for the company, the Chinese partner secretly launched a parallel company. “He reproduced everything and tried to approach our clients with the message that he wasn’t sure our company could deliver but that he himself could deliver. He really had a big plan to corner the business,” says Litjens. But the plan backfired. “The first client he approached called me immediately and told me about it.” This led to a bitter 18-month divide within the company, Litjens says. Eventually, Litjens and his partner closed down the business. Today, the two Dutch partners operate both an FIE and a rep office in China, but use no Chinese partners.

“The first time I came to China, I chose to establish a joint venture with a very powerful [Chinese] partner; [he was] so powerful, he lost us millions of dollars. That way didn’t work.”

Oto Petroski (Macedonia), Founder, Trading company

Macedonian businessman Oto Petroski also experienced such serious problems with his initial Chinese partner that he eventually dissolved the company—but only after suffering serious financial losses. “The first time I came to China, I chose to establish a joint venture with a very powerful [Chinese] partner; [he was] so powerful, he lost us millions of dollars. That way didn’t work. Another friend of mine lost US$1 million through the cheating of his Chinese partner, just like that. He paid a lot of money to the partner to set up things, and then the Chinese partner disappeared.” After those experiences, Petroski formed a second business through the Chinese wife of a new business partner, this time, a trading company operating as a domestically owned firm. In this case, the Chinese wife serves as a silent partner who is not directly involved in the business but enables the company to attain “domestic” status. Petroski says that using this route was “the only possible way” for his company to begin importing and exporting. (See the case study “East-West Partnership Gone Sour.”)

The foreign entrepreneur says he has learned some important lessons. “You can run a business by yourself in China. You don’t need a local person to help you. One of the reasons I got a local person involved originally was that I didn’t have the money to set up an FIE. The minimum requirement was US$140,000. Now, when I look back, I can see that it wasn’t actually all that much money. Now, I would rather just write a business plan and get an investor who has nothing to do with running the business and pay back the loan over three years or something. I would say, ‘Go solo.’ I hear the stories over and over again. People ask me, ‘Why don’t you just get your cash out [of China] and stop?’ But I think I’ll give it one more chance.”

![]() It may be better to go it alone unless you have total trust in your Chinese partner and legal precautions are in place.

It may be better to go it alone unless you have total trust in your Chinese partner and legal precautions are in place.

Effective Partnerships

Despite some cautionary tales from interviewees, many of our profiled entrepreneurs had positive experiences in forming partnerships with Chinese counterparts. For them, teaming with the right Chinese partner was an effective way to enter and expand in the China market. Japanese businessman Fumito Suzuki, who founded AOI Business Consultants with a Shanghainese partner in 1999, believes that cross-cultural partnerships can work for foreign investors. He explains the division of work between the partners: “I am the CEO, responsible for HR, marketing, and getting information about China. My partner, Mr. Ye, is the CFO, responsible for accounting, marketing, and the development of our strategy. I am a Japanese who is not quite Japanese, and Mr. Ye is a Shanghainese who is quite Japanese.” Suzuki says the secret to their successful partnership is mutual respect. “We quarrel a lot in business, actually, but quarrelling is not a bad thing. It constantly reminds us of the possible mistakes so that we can prepare in advance. We complement each other a lot.” The other secret, Suzuki says, is trust and understanding. Suzuki met Ye at university in Japan, which is why Ye speaks “perfect Japanese.” The partners’ history as classmates, and their shared language ability, help to build trust, creating the foundation for cooperation.

Swiss executive Nicolas Musy admits that he found the Chinese partner for his cashmere factory by chance, but says that the relationship has worked well for both sides for nearly two decades. “I met my Chinese partner in a hotel in 1991. I worked for a Swiss trading company and was setting up their operations. As was usual at the time, I was living in a hotel and he was working there as key account manager. We talked and got along very well, and he wondered whether there was a chance that we could work together. At the time, I had just filled a position. Eight months later, I came across him in the street. ‘I have a position for you here now,’ I said. We started working together in the office, and we are still partners today.”

“There are three important elements for success [in choosing a Chinese partner]. One is that the Chinese partner should understand a Western mindset. . . . The second is ethics and trust . . . the third is ability.”

Nicolas Musy (Switzerland), Founder, CH-ina (Shanghai) Co.

Why has the partnership worked well? Musy says the main reason is that he chose the right person to work with. “In my case, there are three important elements for success. One is that the Chinese partner should understand a Western mindset. My partner actually thinks the same as me. The second is ethics and trust. We won’t go for short-term gains at the expense of the relationship. The third is ability. He is a very capable person.”

Ingredients of a Good Chinese–Foreign Partnership

The skill of forming successful Chinese–foreign partnerships is extremely valuable for a foreign businessperson in China, whether you are establishing a domestically owned company or setting up an agreement with a domestic supplier, buyer, or retailer. In this section, our China-based entrepreneurs and consultants offer advice on the following ingredients, which they consider essential for a successful partnership:

![]() Before seeking a Chinese partner, determine exactly what qualities you need based on your business plan. Screen each candidate with a background check, customer assessments, and financial profile.

Before seeking a Chinese partner, determine exactly what qualities you need based on your business plan. Screen each candidate with a background check, customer assessments, and financial profile.

Ingredient #1: Due Diligence in Seeking the Right Partner

Several of the consultants we interviewed were surprised by the number of foreign entrepreneurs who choose their Chinese partners casually, without a thorough investigation of their background, clients, market reputation, and financial holdings. South African consultant Kobus van der Wath put it bluntly: “Don’t choose your [Chinese] partner at the first trade fair you attend. Some people bump into Chinese businesspeople at a trade fair in Germany or Shanghai, and three months later, they have a partnership agreement. Then six months later, they call us and say, ‘I have a problem with my Chinese partner.’ That’s silly. They should have done due diligence and checked the track record.” Van der Wath also warns businesspeople outside China to conduct due diligence on foreign companies selling themselves as “China experts” abroad. “You find many ‘China experts’ in the market, but how long have they actually been in China?”

Doing your initial homework well, Van der Wath advises, begins by researching exactly what kind of partner you need, based on your business plan: “Come in with a clear idea of the direction in which you want to go. I call it the ‘Day One’ strategy.” During the second step—screening qualified partner candidates—Van der Wath advises setting up clear “processes,” such as keeping clear documentation of all negotiations, and sticking to a timeline. “For me, it’s all about process—being intelligent and systematic. In the early stage, the crucial factors are the people, the initial research, and the initial concept.”

Ingredient #2: Shared Goals and Clear Communication

Readers may have heard horror stories of foreign companies forming totally dysfunctional partnerships with Chinese companies. Such disastrous pairings are fewer in China than a decade ago, but are still a reality. Mismatched goals from the two sides can still be a common problem in forming a partnership (or even a long-term sales contract) with a Chinese entity.

Fourteen-year China veteran entrepreneur Shah Firoozi says that one common danger is that both sides misunderstand the value they offer to the other side; this leads to disputes, he says. For example, foreign partners often believe that they carry most of the clout in the partnership because they offer financial resources or technological skills. “Most foreigners feel that if they bring investment and technology, they have the most power. Well, frankly speaking, the investment isn’t a key issue for many partnerships because there are many sources of money available in China. Nor is technology all that important, as it’s also attainable elsewhere.” Firoozi advises foreign entrepreneurs to “always ask yourself: what advantages am I bringing to my local partner? What do they really expect from our relationship?” The real answer may surprise the foreign side, he warns, adding that the Chinese side will only answer this question truthfully once trust and goodwill have been established on both sides.

![]() Find out what advantages you bring to your local partner, in their eyes, and what they expect from you. The answers may surprise you.

Find out what advantages you bring to your local partner, in their eyes, and what they expect from you. The answers may surprise you.

Finally, one of the most common instances of “misaligned goals,” according to our interviewees, is when the Chinese partner sets up a parallel business and steals customers from the original business. Consultant Ruggero Jenna tells of one client who discovered recently that his Chinese partners were developing similar products and distributing them to their clients at a similar price. “It was really difficult to distinguish the [copied] products from the originals. The clients wouldn’t know the difference.” In such cases, the foreign side of a partnership may not know about the problem for months or even years. “It’s tricky, because it’s the company’s own distributors that were doing it. We are talking about a market in which the distributors really own the clients.” Jenna warns foreign investors who are forming partnerships with local Chinese that this problem is common. “Many Chinese partners do this. Eventually, they want to develop their own technology and brands. That is their long-term strategic goal.”

Ingredient #3: Careful, Thorough Initial Negotiations

One way to avoid forming a “poisoned partnership,” in which the two sides have differing goals, is to spend more time and effort upfront in forming the agreement and building the relationship. Consultant Ruggero Jenna says the main reason that many partnerships in China fail is simple: “Usually, the interests of the two partners are not aligned. The upfront negotiation hasn’t been thorough, so there are a number of unspoken issues in the initial stage that the partners didn’t realize existed. At the beginning, everything looked nice and both sides were excited. When problems appear later that weren’t contemplated in the initial agreement, then the partnership usually breaks apart.”

“Usually, [when a partnership fails] the interests of the two partners are not aligned. The upfront negotiation hasn’t been thorough, so there are a number of unspoken issues in the initial stage that the partners didn’t realize existed.”

Ruggero Jenna (Italy), Managing Partner for Asia and Asia Pacific, Value Partners

To protect the foreign side against such a fate, and taking into account China’s often vague rules and the difficulty in enforcing regulations, Jenna advises clients to maintain a strong position in the partnership. “It is very difficult to enforce rules [in China]; and besides, rules are unclear in many cases. In this situation, it’s really a matter of who has the strongest position—the one with the strongest position can impose his view on the other side. It is important to have a position in the partnership that is sustainable over time. Then, in order to protect yourself, you should write a contract. The terms [of the partnership] must be set up in a way that gives you a safe and strong position from the start, and control later on.”

The phenomenon of Chinese partners eventually competing with their international partner is “happening more and more,” warns consultant-entrepreneur Jan Borgonjon. The best safeguard, he says, is “very careful assessment at the beginning,” coupled with close communication and monitoring after the partnership is operating. He says that, unless the foreign partner has created a rock-solid relationship or offers sufficient incentives for the Chinese partner not to go into business himself, the international entrepreneur should actually expect such a development. “You shouldn’t be surprised that it’s happening. As your Chinese partner gets stronger, he can easily enter the same business and use the knowledge he has gained through you. How are you going to stop that? It also happens in the West. Here, it’s simply a risk of doing business in China—and you take it, or you don’t take it. No one is forcing you to come to China.”

“As your Chinese partner gets stronger, he can easily enter the same business and use the knowledge he has gained through you. How are you going to stop that?”

Jan Borgonjon (Belgium), President, InterChina Consulting

In cases of clear breach of contract, attorney Lluis Sunyer says foreign investors in China can go to court. “Many foreign and Chinese companies are trying to solve their cases in Chinese courts of justice these days,” he says. He adds, however, that this option still “normally is not the most time-effective and cost-effective way to solve disputes. In China, as in Spain, we have the popular saying, ‘Win the lawsuit, lose your money’ (![]()

![]() ).” Instead, companies generally try to avoid this route by including in their contracts an arbitration clause spelling out how to solve potential differences. For example, Sunyer says it is “very common” to set the Shanghai Arbitration Commission or the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission as the designated body for submission and solution of disputes between contractual parties.

).” Instead, companies generally try to avoid this route by including in their contracts an arbitration clause spelling out how to solve potential differences. For example, Sunyer says it is “very common” to set the Shanghai Arbitration Commission or the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission as the designated body for submission and solution of disputes between contractual parties.

![]() Take the time upfront to build a solid relationship with your Chinese partner, then hammer out a workable agreement and contract. Maintain a power advantage in your favor to guarantee a degree of control after operations are up and running.

Take the time upfront to build a solid relationship with your Chinese partner, then hammer out a workable agreement and contract. Maintain a power advantage in your favor to guarantee a degree of control after operations are up and running.

Our consultants stressed that one of the best safety nets against such a dispute is to hammer out a workable agreement and contract, and to build a good foundation for the relationship in the initial stage. Shah Firoozi warns clients against the common mistake of delegating the crucial initial negotiations to an assistant or a consultant who has Chinese-language skills but perhaps lacks the right personality. “The Chinese are very personal people. In every relationship, there is a personality in it. What makes the substantial difference is whether both sides connect and relate well. In my opinion, what is not important is language. I’ve seen many companies use a delegate just because he speaks Chinese. This person may or may not present the right communication skills and right personal skills to deal with the Chinese counterpart. The perception of many companies is that if you speak the language or because you are of Chinese roots, of course you can make a deal. It’s very difficult for Chinese returnees sometimes to adapt well to China. In my opinion, I would look at the character of the person. The Chinese have an incredible way of sensing a genuine person from a non-genuine person.”

Ingredient #4: Mutual Respect and Trust

Lack of respect between partners is another common “poison pill” for ventures, our interviewees explained. Spanish consultant Josep Giro tells of a typical situation created when respect hasn’t been established: “In one of our client companies, the Chinese side contributed to the partnership machines which were very old but that they had valued very highly. The Spanish side accepted this because they were busy doing other things. Both of them disliked each other and they cheated each other. If you cheat each other, you can only have a bad result.”

Another critical factor in establishing respect and trust is to send the right foreign managers to China. Foreigners with personalities that clash with Chinese business norms can easily harm, or even destroy, the partnership. Says Shah Firoozi: “I’ve personally seen how the strong personality and character of the partners’ representatives can make all the difference in how the partnership is formed and sustained.” He advises foreign negotiators to “stay very cool with the potential partners and get to know them as people; establish a good relationship with them.” Firoozi believes that a negotiator with a patient, respectful personality is most useful in winning a solid partnership agreement. “In the Chinese partner’s eyes, the critical qualification is not only how much you know about your business, but what kind of character you have. Because, in the Chinese partner’s eyes, you are the window to your company. How you behave is perceived as the character of your company.”

Other consultants stress that successful cooperation can only take place if both sides are culturally sensitive and respectful. Kobus van der Wath explains: “You have to be culturally astute. I can tell within five or ten minutes of talking to them if they are going to do well in a negotiation. In the first few minutes, you can see whether they are going to be brusque, rigid, or rude.” Another kiss-of-death for a partnership occurs when both sides undervalue their partner, says Josep Giro. “When I was negotiating a partnership for a client recently, I asked him, ‘Do you think your company is more important than the Chinese one?’ The client said ‘yes,’ although his company in Spain had only 100 workers while the Chinese company had 200 and the same turnover. I posed the same question to the Chinese side. They also said ‘yes.’ I realized that both were in conflict. They didn’t respect each other.” He adds that unless both sides change their thinking, the partnership “will be a disaster.”

![]() To create a successful Chinese–foreign partnership, both sides must be culturally sensitive and respectful. Personalities matter.

To create a successful Chinese–foreign partnership, both sides must be culturally sensitive and respectful. Personalities matter.

Giro also warns foreign partners against making other common mistakes, including changing the foreign management team too often or quickly firing the Chinese managers. “I know of foreign companies that change their top management [in China] every year or two years. If you hire somebody from the competitors, three months later, you fire that guy and you bring a team of expatriates. Before those guys can make an impact, you replace them again. In this kind of case, you cannot blame the partnership failure on the Chinese side.”

Then, too, some foreign businesspeople behave un-professionally in China, damaging the partnership’s and their company’s image. Says Giro: “Sometimes, people do things in China that they wouldn’t do in Spain. During negotiations for the JV, the Spanish people say, ‘Okay, tonight we go to the bars for drinks.’ I say, ‘Come on, we are negotiating.’ They don’t do that in Spain, but they do it in China. They know they are not acting professionally, but they do it in China.”

Dutch internet entrepreneur Marc van der Chijs believes that respect stems from both sides meeting both “technical and emotional” criteria. “As to the emotional side, we should choose a partner at the same level, with a similar educational background. Thus, we can show mutual respect to each other. We can’t look down upon our partners or control them,” he says.

Conclusion

In terms of finding the money to launch your China-based business, entrepreneurs are advised to be thrifty during the initial period of their ventures, and to exercise careful control over their expenses. Many of our interviewees used their own funds to start their businesses, and only invited venture capitalists to join them after some period of operation. When using outside sources of funding, the entrepreneur should consider the pros and cons of having more funds to grow the business faster in return for giving up some control.

The second topic covered in this chapter is choosing the right Chinese partner—a decision that will have an enormous impact on the future of the business. Our entrepreneurs have had mixed experiences; for some, their partners are like family members, while for others, they proved to be their worst enemies. Before entering into a partnership, they advise foreign entrepreneurs to research and clarify the benefits and obligations offered by both partners to the other, and then to establish an initial agreement that ensures the foreign side maintains its value in the eyes of the Chinese partner. The more time and effort that is spent upfront, the more chance there will be of avoiding a divorce within a Chinese–foreign venture. The four “ingredients” in a successful cross-cultural partnership are: (1) due diligence in seeking the right partner; (2) shared goals and clear communication; (3) careful, thorough initial negotiations; and (4) mutual respect and trust.