CHAPTER 3

Working with Management

This chapter covers the following topics:

• Obtaining management approval

• Defining management’s role

• Inventing a project kickoff

• Creating management alliances

Management. That very word conjures up so many different visions for project managers. For some, it brings up the image of the irate and belligerent boss who’s always unhappy with someone about something. For others, it’s the image of the boss who hides away, dreading to make a decision on anything. Still, for some, management is not a bad word at all. To these people, management is a mentoring, guiding presence that wants projects to succeed.

Whatever type of management you’re dealing with, you have to work with them, and usually answer to them. If you’re fortunate to have a good manager, count your blessings. There are plenty of people out there who would trade places with you any day.

The thing to remember about management is that it’s not necessarily an “us-against-them” mentality. Management’s job is to support the vision of the organization. Their role is to cut costs, increase productivity, increase revenues, and ensure that the requirements of upper management are met. The people you know as management are often in the uncomfortable position of being stuck between the executives and the day-to-day operational staff.

This chapter will examine how you, the project manager, can work with management toward project success. You’ll learn how to present a plan to management, get management involved in the plan, and then work with management as the project progresses.

Defining the Organizational Structure

The way your organization is structured determines the communication requirements, responsibilities, and reporting structure you have with management. The organizational structure, culture, and internal policies also determine the amount of authority the project manager will have in a project. Because all organizations and projects are different from one another (thankfully), they can be broken down into one of three different organizational structures: functional, matrix, and projectized.

Working in a Functional Organization

Functional organizations are fairly common. They are segmented by departments and their “functions.” For example, you may have “Sales,” “Accounting,” “Legal,” “IT,” and so on, throughout your organization. In a true functional environment, all team members, including the project manager, report to their functional manager.

The project manager in a functional organization has very little power. Decisions flow through the functional manager—who is the one running the show. Project managers are sometimes simply called project coordinators or expeditors in a functional structure. The advantage of the functional organization, however, is that there’s less anxiety than in other structures, communication demands are reduced, and team members stay within their departments to complete the project work.

Working in a Matrix Organization

A matrix organization structure allows a project team to incorporate resources from around the organization regardless of which department employees may work in. Project team members can be recruited from anywhere or any place within the organization. In contrast to the functional structure, this structure blends the project team based on team members’ individual contributions and abilities.

Technically a matrix structure has three different flavors:

• Weak matrix The functional managers have autonomy and power over the project team members. The project manager has limited authority on project decisions, much as in a functional structure, except the project team members come from around the organization.

• Balanced The project manager and the functional manager have equal power and autonomy over the project team. While this sounds nice, it’s usually pretty tough to implement. A good balanced matrix defines the decision types that management will make, such as costs and procurement, and leaves the core project management and technical decisions to the project manager.

• Strong matrix The project manager has autonomy over the project and the project team. This structure gives the project manager the most authority, but in reality it’s still pretty tough to implement, as there are many functional managers to work with, budgets to approve, and personalities that affect project decisions.

On paper, the matrix organization looks pretty good, but there are some downsides. Communication demands increase for the project manager because they’ll likely be required to keep all of the project team members’ bosses up to date on how the project is moving and how the team members are doing on it. Team members have to report to at least two bosses: their functional manager and the project manager. In addition, team members can expect to be working on multiple projects at one time, which, of course, increases their responsibilities, communication requirements, and workload. When team members are working on multiple projects simultaneously, the project managers must coordinate schedules, share resources, and communicate even more. Further, team members may be expected to complete their regular job duties along with additional responsibilities on the project.

Working in a Projectized Organization

In this organizational structure the project manager works with complete autonomy over the project. The project team is on the project full time and reports only to the project manager. The project manager has the most authority in this structure. There are many advantages to the projectized structure:

• The project team is on the project full time.

• The project team reports to one boss for the duration of the project.

• The project manager has power over the project.

• Communication demands are reduced.

This can, however, lead to redundancy in some functions, such as tech support, accounting, purchasing, legal, and so on. Additionally, team members do not get the experience they gain when they work in an environment of their peers beyond the project team. This is particularly true for those working in technical fields. What can happen is that a needed resource is assigned to the project but sits idle for a few activities in the project.

Projectized organizations, while they can be efficient and create good teams, do have some negative aspects to consider. First, if a project team member leaves the organization, this can create a hole in the team, cause the project to stall, and require any new team member to ramp up quickly on the project. Projectized structures also face an increase in team anxiety as the project nears completion. Team members may begin to wonder (panic) about what assignment they’ll be doing next as the current project enters its final stages of activity.

Presenting the Project to Management

It’s been said that most people’s number one fear is public speaking—and with good reason. Everyone has witnessed someone making a terrible job of delivering a presentation, so you know the dilemma. The fellow is sweaty, speaking low, and tripping over every word while he’s searching for the next. Poor guy.

Chances are, though, if you were to talk to this person over a cup of coffee about the same ideas, he’d be rational, personable, and able to express his thoughts without a single “um” or “uh.” What he’s got is stage fright, and it’s curable—with practice. The most important thing in a presentation? The message, not the messenger! If you know exactly what you want to say, you can say it much easier.

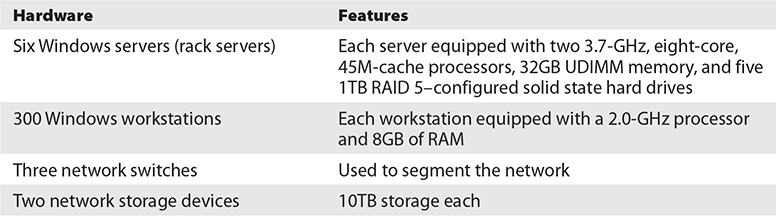

Presentations can be powerful, inspiring, and informative sessions. An effective speaker can captivate and motivate the audience to action. The core of an excellent presentation is the speaker’s intimacy with the topic. The more familiar you are with the topic you are speaking on, the more convincing you will be. You must know your topic to speak effectively. Figure 3-1 shows the building blocks to an effective presentation.

Figure 3-1 An effective presentation must sell the project through effective reasoning.

Start at the End

When you begin a presentation, you want to capture your audience’s attention. You want to hook them and reel them in to your project idea. One of the most effective ways to do this is to start at the end. Tell your audience first what the proposed project will deliver. Forget all the techno-babble—that only impresses geeks. Management wants to hear facts. If you are launching an agile project, you’ll also need to sell stakeholders on how agile project management works differently than the traditional waterfall approach.

For example, Susan is proposing a real-time transaction server for databases across the United States. In her presentation, she could go on about how long each transaction will actually take, the number of processors in each server, and the network connecting each site—but who cares (other than IT folks)? To grab the attention of management, she needs to open with the end result: “Our company will be 33 percent more productive by implementing this technology. From coast to coast, our customers can buy more products in real time with a guarantee of when they’ll ship. Of course, this means our company will be more savvy, more advanced, and more profitable than our competitors.”

Wow! Now Susan really has management’s attention. She now has to back up her statements with the proof she’s already gathered from her initial research. Susan has sold the business value, not the technical solution. Once she has delivered the core benefits of the project, Susan should immediately show her supporting details regarding why she’s so confident the implementation is a good thing. She can do this as a business case, which focuses on the return on investment (ROI) for the project. She could also use a slideshow or charts to show the expected growth.

The WIIFM Principle

The WIIFM, or “What’s In It For Me,” principle is the ability to make a presentation touch the audience members so that they see how they will benefit from the proposal. When an IT project manager pitches an idea, they have to show the audience, typically management, how this technology will make customers’ lives better, improve profitability for the company, and make the company superior. You can rarely go wrong if your proposal focuses on either cutting costs or increasing revenue—or sometimes both. Even not-for-profit organizations are concerned with the profitability of a project as better returns on investments mean better usage of the dollars saved and earned.

Professional salespeople describe this principle as selling the benefits of a product, not just the features. If you do present a feature, always back it up with a benefit. For example, “This new system has eight gigabyte of memory (feature), which will enable each user to increase productivity by 20 percent.” You’re selling the sizzle, not just the steak.

Obviously, whenever you get an idea to implement a new technology, you’ve got some personal reasons: productivity, an easier workload for you, an opportunity to work with technology, career advancement, and maybe some personal reasons you wouldn’t say out loud and would deny even if you were asked. Management will have similar reasons for implementing, or not implementing, your plan. You have to look realistically at four major points in the WIIFM principle to determine if your plan is viable:

• Profitability If the ROI on your project is small or nonexistent, proceed with caution. Remember, all businesses exist to make money; make certain your project supports that goal.

• Productivity Examine how your project can increase the productivity of the company. Not all projects will increase productivity for everyone, but at the minimum it should not hinder productivity.

• Personal satisfaction At the core of WIIFM is the ability to personalize the project. Find attributes of profitability, credit for implementing the technology, new sales channels, and other benefits that will make management (and you) happy to implement the plan.

• Promotion Think of how the project can promote the company’s products, but also think how it can promote careers—not only yours, but the decision maker who will see the advantage of the project and may become your project sponsor.

WIIFM is not all about greed. It’s thinking for the other parties. It’s showing them the need that they may not see. WIIFM is creating a win-win solution for the parties involved. There’s nothing wrong with thinking about the interest of the parties you are pitching your presentation to—in fact, it’s required if you want their approval.

In many instances, the project manager gets the project dumped in their lap, a slap on the back, and a hearty handshake. In other words, there’s no pitch to management, or anyone else, to get the project off the ground. An effective project manager, however, should investigate why this project is needed, how it helps the organization, and what exactly the project must deliver.

Tailor the Presentation

If you are speaking to a group of executives who have but a few minutes to hear your proposal, you need to get to the point quickly using terms they can understand. Forget about processors and bandwidth altogether with this crowd—focus on the benefits. If you’re pitching to a group of managers who have a background in technology, then show them the details of the technology and how it increases productivity, profitability, and sales. Figure 3-2 shows the overlapping scopes a project manager must consider when addressing an audience. The point is to know your audience ahead of time and tailor your presentation to that audience.

Figure 3-2 Project managers must address several factors in a presentation.

If you are presenting your solution to a group composed of upper management, middle management, and your immediate supervisors, always address your presentation to the decision makers—typically upper management. Whomever you are speaking to, tailor your presentation to what they want, and need, to hear to make a decision. Here are six tips to help you do so:

• What is your track record? Discussing the successful projects that you’ve completed gives confidence to management to invest in new projects you propose. It works the other way, too: If you’ve gained approval in the past but blew the implementation, that’s valuable experience for you and them. If you’ve worked as a project manager before and failed miserably, management is going to be less excited to give you another opportunity until you can prove yourself again as a team player in other project implementations. Consider the lessons learned from the prior project and how they can help you on this new project. You may want to approach your immediate boss and seek her input.

• Do they really want to listen? You need to determine if this is the best time to even be talking about new ideas. If the organization is in turmoil financially, emotionally, or technically, your chances are diminished for implementing new projects—unless your project can resolve the turmoil.

• Are they listening? Remember, you’ve got to speak the language your audience needs to hear. Describe your project and its deliverables in the business terminology your audience speaks, and you will be heard. A business case defines the problem or opportunity, the approach the project will take, and the anticipated return on investment.

• And who are you again? If you’re low in the hierarchy, you may have big ideas but little track record. In this instance, your idea may be valuable but you aren’t recognized—yet. Partner with someone in the organization who is a valuable leader and work with that person to pitch and manage the project. Use teamwork.

• How does this project help? If you are getting this question from your audience, then you have not started your presentation at the end, as previously discussed. Show them, in their language, exactly how this project helps. Show them how it increases profitability, what the ROI is, and why it should be implemented. In your organization, this task could be up to the business analyst, not the project manager. Know the rules before you start playing.

• Are you following the rules? You need to know the rules, and you need to follow the rules. Does your organization have formal or informal guidelines and procedures to pitch new projects? If so, follow these rules. Other organizations, and people, have enough on their plates that they won’t dream of starting a new project until they can catch their breaths on their current assignments. Find the rules to make a project a reality and follow them.

For each presentation, it would behoove you to have handouts of your overheads, charts, graphs, and any other pertinent data. Your feasibility study is ideal for this collection of handouts if you’ve had the opportunity to complete one. Whatever you decide to disperse, always include an executive summary near the front of the study so that the reader can skim over the details and get the hard-hitting facts first. Of course, you should write the executive summary with your audience in mind. For formal meetings you should utilize a scribe. A scribe is a person that records the meeting minutes, business discussed, questions, and other important notes for your meeting. After the meeting, the recorded information, action items, and follow-up information are compiled and distributed to the meeting members.

Role of a Salesperson

Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of Treasure Island, said, “Everyone lives by selling something.” No matter what you do for a living, you are selling something: time, wrenches, advice, a service, or a product. When it comes to presenting your idea to management, you have to slip into the role of salesperson.

When you think of sales, dismiss the high-pressure used-car salesperson stereotype. A good salesperson is someone who identifies a need and then helps to fulfill it. That’s what you have to do here. You’ve identified a need through your research, and now you may have to show management where that need exists and how this technology will fill it.

When you’re selling an idea, speak in direct, simple terms. If it takes you longer than five minutes to express the reason for the technology, you’re taking way too long. In fact, an excellent summary of the technology and its benefits should take less than a minute. For example, if you’ve determined the solution to the problem you’ve been presented with is to implement Adobe InDesign for your web designers, provide the supporting evidence for your recommendation. You have done the research, interviewed the developers, and explored the cost of the decision, right?

To open the presentation, you’d say something to the effect of, “Adobe InDesign will increase productivity, streamline the efforts of our web designers, and allow for collaboration of in-house and external developers. The time saved alone will pay for the product in less than a month.” (This is assuming you have the evidence to support this statement.)

Again, you’re starting at the end, but the whole idea and pitch is done in less than a minute. You need to capture your audience’s attention and draw their interests into the plan. Everyone wants to be part of an investment that works. Show them immediately how your plan will work and then invite them to participate.

Included in the presentation to management is an informal presentation. You may know this as the infamous “elevator speech.” You know the drill: The CEO sees you in the elevator and asks, “So what are you working on these days?” And then you can sum up your project in 20 seconds or less on your elevator ride. This elevator speech is handy to summarize your project to anyone, anywhere. Agile projects may call this elevator speech the project vision statement.

The role of the salesperson in project management isn’t really about sales—it’s about marketing. You need to market your project to gain stakeholder support. Whenever a stakeholder first hears about a new project in the organization, especially a technology project, there’s some immediate anxiety lurking beneath the surface. When an organization changes technology, it changes the way people work. People get accustomed to doing their work a certain way. People know that learning and mastering a new technology takes time. And people know that there are unknown risks in new technology: risks for how they’ll work with the technology—not necessarily risks for your project, but from their perspective.

Marketing the project means you’re helping stakeholders understand the vision of the project and why the project is needed. You address the negative aspects of the current state, and then you address how the new technology your project will implement will solve those negative aspects. Your goal is to help reduce fear, reduce perceived threats, and gain buy-in from stakeholders. You want stakeholder support, and you can get this by speaking with and involving stakeholders early in your project. Let’s face facts: people want to be listened to, to feel that their concerns are being addressed, and feel that they are part of the project solution rather than just having a project solution forced upon them.

Defining Management’s Role

Management, to some, is a necessary evil. Sure, there are plenty of bad, heartless bosses in this world, but not every manager is bad. The majority of managers want to be good bosses, they want to be well liked, and they want to do a good, thorough job. While management should show an interest in the project you’re implementing, their role should be one of support, not one of implementation. Management should not be peering over the shoulder of a technician trying to install video cards and memory.

Project sponsors, however, do have an active role in the project management experience. Figure 3-3 shows the relationship between the project sponsor, the project manager, and management. Project sponsors need to be informed of the status of the project, of who is completing which portion of the project, and of how the project is doing on time and finances.

Figure 3-3 Project sponsors are mediators for project managers and management.

Project sponsors have invested their credibility in the implementation, and they are relying on you to report progress and to complete the work. Project sponsors, like management, should not be peering over technicians’ shoulders, but should, in some cases, attend team meetings, be involved with the project planning phases, and have input on the project implementation. Don’t be afraid to ask questions and share concerns with your project sponsor—the sponsor is on your side and wants you to succeed with the project.

In fact, if you are going to present the project, it is in your best interest to talk with the project sponsor ahead of time and get coaching on the presentation. Find out the hot buttons, allies, showstoppers, and so on. Then you can tailor your presentation to incorporate this information. If you are pitching a project that does not yet have a project sponsor, see if you can get some input from a likely sponsor or a friendly person in senior management. It always helps to stack the deck in your favor a little bit.

If you’re working with a project management office (PMO), then your conversations and coaching may come from the PMO rather than the project sponsor. Recall that the PMO will help the project managers follow a standardized approach to most aspects of project management. The initiation, planning, and closing phases of a project are where most PMOs direct the processes, workflows, and involvement with the project managers. There are many variables, of course: the depth of involvement of the project sponsor, the PMO, and the stakeholders of the project. Each organization, like each project, is different; understand the expectations of your organization before venturing too deep into the project.

How Projects Get Initiated

Organizations have only so much capital (aka cash) to invest in new projects and opportunities. In most organizations, projects just don’t get launched without first moving through some business analysis procedures to determine the worth of the project to the organization. The selection of the project can focus on its cost, its associated risks, or—most likely—what it will return to the organization for the investment.

While many projects are viewed by management as only a financial investment, there are usually many other factors that influence project selection: new laws and regulations, new technology, complaints from end users, competition, customer requests, and more. The formulas and mathematical approaches I’m about to share with you are rarely the only reasons why a project gets initiated, but these are almost always part of the conversation when it comes to launching a new project.

You can help yourself by being familiar with how your organization determines which projects are funded and initiated and which projects are declined. Knowing how your organization chooses a project will help you research solutions, prepare for management questions, and generally look like a genius. The project selection approaches described in the following sections are the most common and are often called benefit measurement methods for project selection.

Murder Boards

If your organization requires that project managers and technical gurus be interviewed before the project is funded, you’re likely participating in a murder board. A murder board is a committee that asks every conceivable negative question about the proposed project. Their goal is to expose strengths and weaknesses of the project—and kill the project if it’s deemed too risky for the organization to commit funds to. You might also know this approach as the kinder-named project selection committee or portfolio management board.

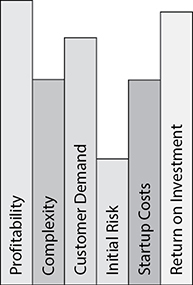

Scoring Models

Scoring models (sometimes called weighted scoring models) are models that use a common set of values for all of the projects up for selection. The common values can be profitability, complexity, customer demand, initial risk, startup costs, and expected return on investment. Each of these values has a weight assigned to it—values of high importance have a higher weight, while values of lesser importance have a lesser weight. The projects are measured against these values and assigned scores according to how well they match the predefined values. The projects with higher scores take priority over projects with lesser scores. Figure 3-4 demonstrates the scoring model.

Figure 3-4 The weighted model bases project selection on predefined values.

Benefit/Cost Ratio

Just like the name implies, a benefit/cost ratio (BCR) model examines the cost-to-benefit ratio. For example, typical measurements include the cost to complete the project and the cost of ongoing operations of the project product compared to the expected benefits of the project. Consider a project that will require $800,000 to create new software, market the software, and provide ongoing support for one year. The expected net profit on the product, however, is $1,500,000 in year one. The benefit of completing the project is greater than the cost to create the product. You can go into much more detail and consider costs such as the learning curve, competency levels required, market conditions, and even competition. BCRs are often used in the cost-benefit analysis of determining whether or not a project should be initiated.

The Payback Period

How long does it take the project to “pay back” its costs? For example, your project may cost the organization $500,000 to create over two years. The expected cash inflow (income) on the project deliverable, however, is $65,000 per quarter. From here, it’s simple math: $500,000 divided by $65,000 is nearly eight quarters, or a little less than two years, to recoup the expenses.

This selection method, while one of the simplest, is also the weakest. Why? The cash inflows are not discounted against the time it takes to begin creating the cash. This is the time value of money. The $65,000 per quarter five years from now is worth less than $65,000 in your pocket today. Remember when sodas cost a quarter? It’s the same idea. The soda hasn’t gotten better. The quarter is just worth less today than it was way back then. You might also know the payback period as the management horizon or the break-even point.

Considering the Discounted Cash Flow

Discounted cash flow accounts for the time value of money. If you were to borrow $500,000 from an investor for five years, you’d be paying interest on the money. If the $500,000 was invested for five years and managed to earn a whopping 6 percent interest per year, compounded annually, it’d be worth $669,112.79 at the end of five years. This is the future value of the money in today’s terms.

The magic formula for future value is FV = PV × (1 + i)n, where

• FV is future value

• PV is present value

• i is the interest rate

• n is the number of time periods (years, quarters, and so on)

Here’s the formula in action with the $500,000 invested at 6 percent for five years:

FV = 500,000 × (1 + 0.06)5

FV = 500,000 × (1.338226)

FV = $669,112.79

$500,000 today is worth $669,112.79 in five years. So how does that help? If your organization invests $500,000 in your project and it is is worth less than $669,112 when it’s complete, it’s not worth doing from a purely financial standpoint. When four or five projects are up for selection, management can review the future values of their investment to see which project is worth investing today’s dollars in.

While it’s somewhat easy to determine what needs to be invested in a project, management may also want to see what a project will actually earn the organization. Sure, some of this is “blue sky” predictions, but you should have some evidence of what a project will earn the organization for investing its capital into your project. The earnings a project promises can then be evaluated to determine what the future value of the project is worth in today’s dollars. In other words, if your project promises to be worth $750,000 in three years but it needs $420,000 to get started, management can examine what the $750,000 is worth in today’s dollars. Management is looking for the present value of the promised future cash: PV = FV ÷ (1 + i)n.

Let’s take the project that promises to be worth $750,000 in three years and determine its present value. You can plug the values into the present value formula (assuming the interest rate is still 6 percent):

PV = 750,000 ÷ (1 + .06)3

PV = 750,000 ÷ (1.191)

PV = $629,714.46

So, $750,000 in three years is worth $629,714.46 today. This project needed $420,000 to launch, which is still considerably less than the present value of the project’s completion. This is a pretty good investment for the organization. Now imagine if we had four different projects with various times to completion, costs, and expected project cash inflows at completion. We could calculate the present value and choose the project with the best present value, since it’ll likely be the best investment for the organization.

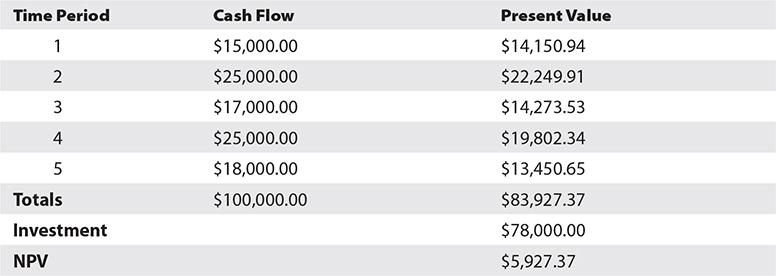

Calculating the Net Present Value

The net present value (NPV) is a somewhat complicated formula but allows a more precise prediction of project value than the lump-sum approach found with the PV formula. NPV evaluates the monies returned on a project for each time period the project lasts. In other words, a project may last five years, but there may be a return on investment in each of the five years the project is in existence, not just at the end of the project.

For example, a retail company may be upgrading the facilities at each of their 1000 stores to make shopping and purchasing easier for their customers. As each store makes the conversion to the new point-of-sales (POS) software, the project deliverables will hopefully begin generating cash flow as a result of the project deliverables. The organization can begin earning money when the first store completes the conversion to the new software. The faster the project can be completed, the sooner the organization will see a complete return on their investment.

In this example, an interest rate of 6 percent per year is assumed. The following outlines how the NPV formula works:

1. Calculate the project’s cash flow per time unit (typically quarters or years).

2. Calculate each time unit total into the present value.

3. Sum the present value of each time unit.

4. Subtract the investment for the project.

5. Examine the NPV. An NPV greater than zero is good and the project should be approved. An NPV less than zero is bad and the project should be rejected.

When comparing two projects, the project with the greater NPV is typically better, though projects with high returns early in the project are better than those with low returns early in the project. The following is an example of an NPV calculation:

Management Theories

Your relationship with management, and how management sees their relationship with their employees, has been theorized and debated for years. As the project manager, these management theories can help you not only realize how management views you but also manage your own project teams more successfully.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

You’ve heard of Abraham Maslow, right? According to the psychologist’s 1943 paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” people go to work to satisfy their hierarchy of needs. Basically, if we satisfy our most basic needs, we can strive toward self-actualization, which enables us to contribute and use our skills and talents. Here are the five layers of Maslow’s hierarchy:

• Physiological People need these necessities to live: air, water, food, clothing, and shelter. People need a place to work.

• Safety People need safety and security; this can include stability in life, work, and culture. People need a safe working environment—with job security.

• Social People are social creatures who need love, approval, and friends. People want to participate with their colleagues and peers—and to be liked at work.

• Esteem People strive for the respect, appreciation, and approval of others. People generally want to do a good job and complete their projects.

• Self-actualization At the pinnacle of their needs, people seek personal growth, knowledge, and fulfillment. People want to excel and work at something they enjoy and feel is valuable.

McClelland’s Acquired Needs Theory

Psychologist David McClelland developed his acquired needs theory based on his belief that a person’s needs are acquired and developed over time. These needs are shaped by circumstances, conditions, and life experiences for each individual. This is also known as the “Three Needs Theory,” because he identified three basic needs for each individual. Depending on the person’s experiences, the order and magnitude of each need shifts:

• Need for achievement People who have this dominant trait avoid both low-risk and high-risk situations. Achievers like to work alone or with other high achievers, and they need regular feedback to gauge their achievement and progress.

• Need for affiliation People who have a driving need for affiliation look for harmonious relationships, want to feel accepted by people, and conform to the norms of the project team.

• Need for power People who have a need for power are usually seeking either personal or institutional power. Personal power-seekers generally want to control and direct other people. Institutional power-seekers want to direct the efforts of others for the betterment of the organization.

McClelland developed the Thematic Apperception Test to determine what needs drive individuals. The test is a series of pictures, and the test-taker has to create a story about what’s happening in the picture. Through the storytelling, the test-takers will reveal which need is driving their lives at that time.

Herzberg’s Theory of Motivation

Frederick Herzberg, a psychologist and authority on the motivation of work, believed two agents affect people and their views toward their careers and work:

• Hygiene agents These elements are the expectations all workers have: job security, a paycheck, clean and safe working conditions, a sense of belonging, civil working relationships, and other basic attributes associated with employment.

• Motivating agents These elements motivate people to excel. They include responsibility, appreciation of work, recognition, the chance to excel, education, and other opportunities associated with work beyond financial rewards.

Herzberg’s theory says the presence of hygiene factors will not motivate people to perform, because these factors are expected. However, when these factors are absent, workers are demotivated. The motivating agents inspire workers to strive for success. The tricky part, however, is knowing exactly what motivates the workers. Your motivating agents may not be anything like the motivating agents of the person working next to you.

McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y

In MIT psychologist Douglas McGregor’s two theories, Theory X and Theory Y, management’s view of their workers is divided into two categories: bad and good. X people are lazy, must be micromanaged, and generally cannot be trusted. Y people are wonderful people who are self-led, motivated, and can accomplish new assignments proactively. In reality, sometimes you, the project manager, must be both X and Y, depending on the scenario, the person you’re managing, and what you want the outcome of the scenario to be.

Ouchi’s Theory Z

Business management professor William Ouchi’s Theory Z is based on participative management. His theory states that workers are motivated by the commitment, opportunity, and advancements provided by the organization employing the workers. Workers have a lifetime-employment mindset and learn the business by moving up through the ranks of the organization.

Vroom’s Expectancy Theory

Yale Professor Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory states that people will behave based on what they expect the results of their behavior to be. In other words, people will work in relation to the reward they expect for their work. If the reward is desirable to workers, they will work to receive it. People expect to be rewarded for their efforts.

Delegate Duties

In this discussion of how a project manager works with management, it also needs to be acknowledged that project managers are now part of management. If your organization has an “us-versus-them” mentality toward management, then it’s up to you to bridge the gap. As a project manager, your team, especially a newly created team, may not fully trust you at the project’s conception—which may be too bad, considering that your team will probably be made up of your friends and colleagues. You’ll need to do your best to work with them—not against them—and earn their trust and respect.

One of your first challenges will be a delegation of duties. Delegation is necessary. You are the project manager, and you cannot do every task required of a project. Once the team has been created, you need to follow the path the management and the project sponsor have taken: put your trust in others so that they can do the job you’ve assigned to them. Predictive projects assign tasks to specific roles, while agile projects teams are self-led and self-organizing. This means the team will determine who’ll do what tasks in each iteration rather than have assignments from the project manager.

Have you ever had the experience of someone asking you to do a task, only to stand over your shoulder and question every move you make? Or worse, have a boss watch you without saying a word? It’s frustrating, to say the least. As a project manager, don’t do this.

Once you have pitched the idea to management and your project has been approved, it’s up to you to make it happen. It’s easy to be tempted to do every piece of the project planning, or at least the exciting parts, but it’s not wise to yield to that temptation. An effective project manager assembles the team, assigns tasks based on qualifications and credentials, and then trusts his team to perform.

Chapter 7 will detail the complete process of assembling and working with a team. For now, know that you are also considered management once you become the project manager. All those nasty thoughts and dislikes you have harbored for some managers can very easily be sent your way now from your team. As you start the project, consider these points to being an effective project manager:

• Follow management. Take management’s lead and delegate as they’ve delegated. If you like the way certain managers have treated and challenged you in the past, follow their lead and do the same for your team. If you don’t like the way some managers have delegated duties, find a role model and follow that manager’s lead.

• Delegation is necessary. You can’t do everything. By delegating duties, you are showing respect, trust, and wisdom to your team. As you move further and further into project management, you also move further and further from technology. Soon there will be a gulf between what you know and the present technology. A successful IT project manager must release the reins of the implementation to the project team members; they’re closest to the project work.

• You are in charge. From the onset, as you delegate activities, be fair—but also remember you are in charge of the project. Establish the flow of communication from your team to you, not around you. Remember that your authority is related to the type of organizational structure you operate in (functional, matrix, or projectized) and that the organizational structure affects the amount of authority the project manager has over the project team. Know what your authority is and then manage and lead to get the project done.

• Remember the users. As your project develops, don’t forget to consistently address the needs of the users impacted by this technology change. Often it’s easy to overlook the individuals affected by the project you are managing. At each phase of the project, remember to ask how this impacts the users of the technology.

• Keep the big picture in mind. As a project manager, you need to make decisions regarding trade-offs and resources that benefit the organization as a whole, not just you, your team, or your project. Develop the ability to see the macro environment and the details. This will take some getting used to, but it is an ability that will serve you well.

• Learn how to speak different languages. At times you will need to present the status of your project to senior managers. They speak a language of ROI, productivity, and competitive advantage. However, your team members communicate in techno-speak. Make sure you are speaking appropriately to the various audiences you address.

• Delegate, delegate, delegate. I mentioned this earlier and it bears repeating—as a project manager, you will have plenty of work to do: following each team member’s successes and failures, tracking the status of the project, meeting with management, meeting with the team, and meeting with team members one-to-one. You need to delegate the tasks and leave them delegated. If a team member is having trouble with a task, then offer your assistance.

You are responsible for the project’s success, the motivation of the team, and the communication with management. If this project fails, it is your fault. If the project succeeds, then everyone shares the glory. That’s just the nature of the beast.

Focusing on the Results

Management’s role is to help you, the project manager, focus on the end results. From the 1940s through the mid-1980s, management typically decided what task needed to be done, who would do it, when they would do it, and how it would be done. To complicate matters more, management would often supervise each step of the process to ensure that it was being done right. You know this, no doubt, as micromanagement.

Today’s management philosophy is more laissez-faire—a hands-off, empowered approach to allowing teams to accomplish a goal. Management today is more concerned with results rather than the process of getting there. As a project manager, you, too, must adopt this strategy. You must recruit your team and then let the team do the work. Focus on the results, be available when you are needed, but allow the team to work.

Of course, this all sounds wonderful, but in reality it is hard to implement. It’s tough to allow others to continue with a project you’ve created. It’s difficult for others to have the same passion and drive that you do about a project. It’s fearsome to put your future and your project’s success in the hands of others. But, remember, you are not giving up ownership or control, you are allowing your team to do the job that you’ve asked of its members.

One of the best ways to create a team with drive and charisma is to, if at all possible, involve the team from the start of the project. By recruiting team members early and giving them responsibility early on, you have given them ownership in the project’s success. A project manager, keeping the project results in mind, must have

• The ability to encourage participation from all members

• The ability to empower team members

• The ability to inspire team members and management

The project manager doesn’t own the project or the project team. The project manager coordinates, directs, aligns, motivates, and leads the project team to accomplish the work. If you want to get people involved in your project, allow them to own the project, too. This means more than lip service about shared ownership and synergy; get the project team involved and let them make decisions about the project work, and then allow them to prove themselves by accomplishing activities and tasks. If you want people to do a great job on the project, delegate the work and then let the project team actually do the work. Get out of the way.

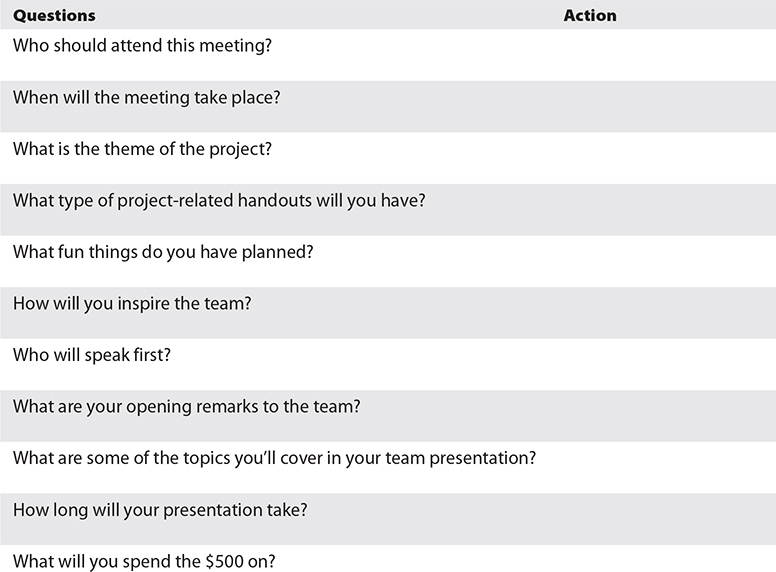

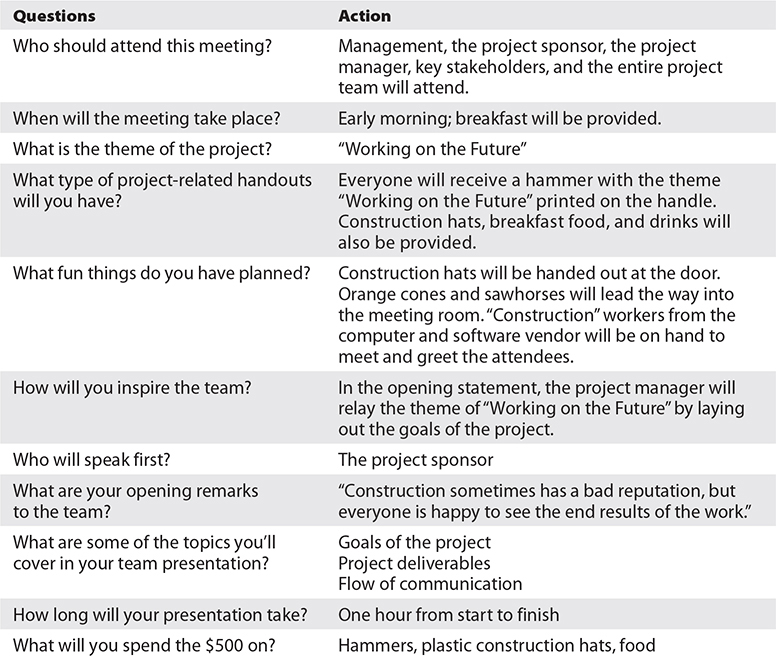

Inventing a Project Kickoff

Every project requires a project kickoff. So what is it, how do you host one, and why is it needed? A project kickoff is a meeting—or an event—to introduce the project vision, the management backing the project, the project manager, and the team members. It should be friendly, yet authoritative; organized; and used as a mechanism to assign ownership of the project to the team.

A kickoff meeting is an opportunity for the key project stakeholders to hear and confirm the details of the project requirements, to get acquainted with the project goals, and, whenever possible, to review the approved project scope. A kickoff meeting isn’t an opportunity to debate the project requirements, add new demands, or workshop new ideas for the project. It is a meeting to confirm the agreement of what the project will and won’t do for the organization.

A project kickoff is needed to establish the launch of the project, who’s in charge of the project, and who’s in control of the project team. This event allows management to rally the troops, organize the team, and get everyone excited about the upcoming plans. It’s also an opportunity to convey the expectations, roles, and responsibilities of all stakeholders. It’s a bon voyage party—but, hopefully, not for the Titanic.

Set the Stage

Depending on your project or your organization, your team may comprise longtime colleagues or complete strangers. Use this opportunity to create a team—or at least the start of one. As the project manager, you are responsible for this collection of individuals, so you need to create a social environment of ownership and teamwork.

In the kickoff meeting, you can set the tone for the entire project. Most project managers want a sense of camaraderie but also a sense of formality to the project. Here are some recommendations of how you can create both for your project kickoff depending on the size, priority, and overall effect the project has on the organization:

• It’s an event! Have some fun. Create a simple theme and have some prizes or handouts for the team that are relevant to the project. For example, using the theme “Together we grow,” give each team member a small plant at the meeting, and tell the team that as the plants grow, so will the project. Remind them that the project needs daily nurturing, just like the plant.

• Get excited! It’s okay to have fun at these meetings. If it’s a major project, and management allows it, hire local professional cheerleaders to “cheer on the team.” Have someone from the local zoo bring in some animals to jumpstart the event. Do something creative and unexpected.

• Invite a representative from the vendor whose technology you will be using, such as Cisco or Oracle, to give a pep talk to the team at the kickoff meeting.

• Have someone take candid photos of team members as they enter the room and then a group photo. Create an intranet page with each member’s photo, bio, and contact information.

• If you can, schedule the meeting close to breakfast or lunch and order in food. Food has a wonderful way of bringing down walls and helping people to mix and mingle.

Project kickoff meetings can be boring and stuffy. Do something exciting, invigorating, and memorable. Create alliances between you and management and the project team. Invoke excitement, assign ownership of the project, and ask for a commitment to excellence. There is no reason why kickoff meetings can’t be exciting. Anyone who says otherwise is a bore.

Timebox the Meeting

Timeboxing means that there is a time limit for the meeting. You do not want the project kickoff meeting to be a long-winded discussion about the merits of the project, how the project will take place, or who’ll do what in the project. Timeboxing states how long the meeting will take place, something you should define in the agenda. You’ll use timeboxing to keep everyone in the meeting on task and to the point. Deeper conversations can happen post-meeting or during project planning sessions.

How Management Fits In

At the kickoff meeting, invite all of the managers involved in the decision. Their presence signifies their commitment to the project. They don’t have to stay for the whole meeting, but they should at least make an appearance to rally the troops and have a donut.

The project sponsor, however, should stay for as much of the meeting as possible. Ideally, the project sponsor should initiate the more formal part of the meeting by calling things to order and introducing the project scope. The project sponsor should speak for a few minutes on the value of this project and what it means to the organization. Then the project sponsor should introduce you as the manager of the project and clearly state your authority level on the project.

This approach signifies a role of authority among the team members without having to say who’s in charge. Obviously, the project sponsor is the management most closely associated with the project, but the central line of contact between the team and the project sponsor is through the project manager. There needs to be a clearly defined path of who is in charge of the project. Projects are not a democracy; each team member should have input and some autonomy, but the success of the project rests on the shoulders of the project manager, so this individual must establish their authority.

Defining the Purpose

Once the project sponsor has introduced you to the team, you’re on. This is your opportunity to define many things. Prepare yourself prior to the meeting regarding what message you want to convey to your team. Your opening remarks should do several things:

• Establish your role as the project manager.

• Clearly state the goal of the project.

• Define the objective of the project.

• Set the tone of how you’ll manage the project.

• State the expectations of the different stakeholders in the meeting.

• Express the impact that the project will have on the organization.

In these opening remarks, you will confirm the purpose and importance of the project and assign that ownership to the team. Don’t drone on and on about the project—the project’s already been approved and there’s no reason to continue selling.

If possible, present a slideshow of what the project will include. You can walk the team through a five- to ten-minute overview of the project’s origin to the deliverables that signify the project has reached its end. There’s no need or real possibility to have a detailed step-by-step plan yet. A simple timeline of each of the major milestones will be fine.

Once you’ve defined the purpose of the project, showed the team members the big game plan, and given them a sense of ownership, you can quit talking. You should be able to do all of this in 15 minutes or less. Yes, 15 minutes or less. Preferably less. The project team is already going to know much of what the project is designed to accomplish. This is an opportunity for the project team, management, the project sponsor, and you to all agree what the project should accomplish.

Finally, show how management fits into the plan. Show how a financial commitment has been made to the success of the project. Show how this team is responsible for the success of the project and how everyone is counting on them.

If possible, share the news of what failure would cost the organization and the impact any delays may have on the project. This isn’t to scare the team into submission, but rather to create a sense of responsibility for the success. Of course, also share with them the benefits the organization will reap when the team does succeed.

Creating Management Alliances

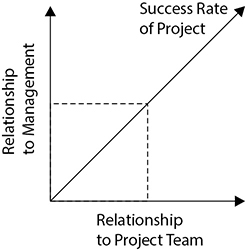

You and management are also a team. Just like you want your project team to be dedicated, to trust you, and to work with you, the same applies in your relationship to management. You and management are working together for the good of the organization, striving in unison toward an obtainable goal. Figure 3-5 shows how your relationship with management can be reflective of how you manage your own project team. While it may not always feel that you and management are part of the same team, you are.

Figure 3-5 A working relationship with management is required for project success.

When management and you agree to implement a new project together, either by your choice or theirs, a team has been created. Hopefully, your management will be as supportive of you as you are of your own team. All of this is directly influenced by the organizational structure you’re working in; functional, matrix, and projectized organizations affect the project manager–manager relationship, but overall the principles in this section are valid for any organizational structure.

Working Together

The first step in this team of you and management is to acknowledge the ability to work together. Whether you like the immediate management you are working with or not, you have to work with them. Keep in mind that your goal, the success of the project, can be impacted by the management you are working with. Likewise, the success of your project can impact the management you are working with. In other words, it’s a symbiotic relationship—you both need each other to be successful.

The solution to working together is to create a channel of communication. You and management must be able to talk, to discuss the project, and to report on the status of the work, the finances, and expectations.

Your communications plan, which I’ll detail in Chapter 6, will dictate how often you and management need to communicate. In some organizations, it’s weekly; in others, it’s monthly. How will you know? Ask management what their expectations are. In some instances, conditions within the project will prompt immediate communication. Basically the communications management plan defines who needs what information, when the information is needed, and the modality of the expected communication.

Intermediary communications in the shape of e-mails, an intranet site, or voice mail would be another avenue to keep management involved with the status of the project. By keeping a flow of communication open through you to management, you are ensuring management’s involvement—but at a happy distance. Project managers must report both good and bad news. Don’t candy-coat your findings; reporting both the good and the bad on an equal scale will build trust between you and management.

There are some problems that management and project managers together need to avoid. One of the largest complaints IT project managers have is that management will circumvent their position and go directly to the project team with instructions, input, and advice. In some instances, such as disciplining a team member, this action may be appropriate. The organizational structure will influence how project sponsors and other stakeholders communicate with the project team. Ideally, project sponsors should follow the same flow of communication through the project manager to the team.

While this flow of communication may require delicate handling, it’s not impossible to achieve. At the conception of the project and prior to the project kickoff meeting, you, as the project manager, should express to the project sponsor that you would like to handle all avenues of communication and management of the project. If you’re new to project management, this chain of command may not be granted, although it’s not unusual. Most professionals respect the chain of command from management, to project manager, to the individuals on the team.

If, for some reason, members of management do bypass you and work directly with your team and this is disrupting the project, you must address the issue. Report to your project sponsor that this confuses the project team about your role as project manager and to whom they are to report, and it undermines your authority with the team. Don’t be confrontational, but do be factual.

Following Organizational Governance

Organizational governance is a nice way of describing the rules and policies that you, as the project manager, must follow in your organization. Organizational governance describes the policies and rules that are unique to your organization—things like how you manage your team, forms you’re required to use, processes you must complete, and how you get to buy resources for the project. You’ll also encounter organizational governance when you complete a project phase and there’s a review, sometimes called a phase gate, before the project can transition to the next project phase. Governance often comes from the PMO, if one exists.

Organizational governance for most organizations includes the internal process compliance—proof that you have followed the internal policies of the organization. This means your project will undergo audits for both process completion and financial reconciliation. Your project time, cost, and scope baselines will also be examined to see where changes entered the project, how the baselines were adjusted to reflect the approved changes, and how you completed versioning of each baseline. A change log is a document to record all changes to the project scope, schedule, and costs, and that’ll help with any audits.

I’ll talk more about change control in Chapter 10, as change is inevitable in IT projects. Changes, in a predictive project, must always follow a defined change control process, be documented, and be incorporated into the project plan for execution. Remember that in agile projects, change is welcome and expected. Most organizations use a change control board (CCB) to oversee significant changes to the project. Sometimes the change control board is known as a technical review board, an engineering review board, or a technical assessment board. These boards all do the same thing: review the change to determine its impact and value on the project deliverable.

Another aspect of organizational governance is how the project adheres to standards, regulations, and corporate compliance programs. A standard is a guideline that’s appropriate for your industry—such as how network cables are punched down. No one’s going to be fined for not following a standard exactly, but standards are the generally accepted practices for a type of work, service, or product. A regulation, however, is a law that your project must follow. Think of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) or the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. These are just two examples of laws that are now requirements for many project managers to contend with. As a rule, standards are optional while regulations are not.

Finally, your organization may participate in quality assurance programs such as Six Sigma or Total Quality Management. These are part of your organizational governance if your project is also required to participate in them. A common requirement of project managers is to map their projects to an ISO program such as ISO 9000:2000. ISO 9000:2000, from the International Organization for Standardization, is based on the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL).

If your organization uses a program for quality and standardization, then the program is part of your organizational governance and your project will need to adhere to it. You might also have to deal with the CMMI—the Capability Maturity Model Integration. Don’t expect many CompTIA Project+ exam questions on this process improvement program, but it’s becoming a fairly popular system for IT project managers (especially if you’re dealing with projects for the U.S. government).

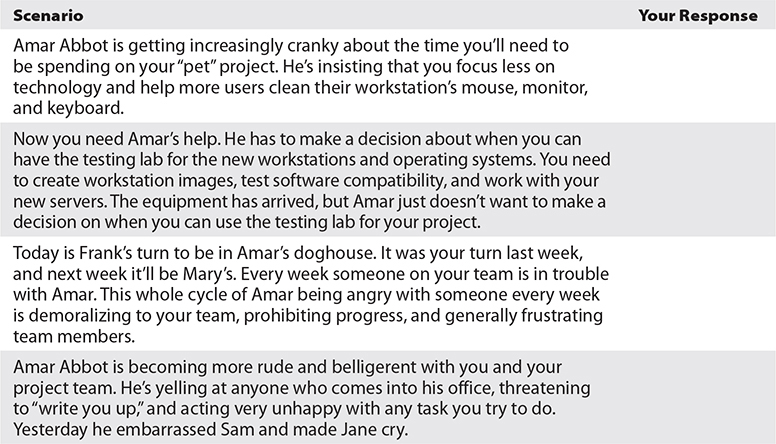

Dealing with Challenging Bosses

Remember the boss who was a complete jerk? Or the one who would disappear for days and avoid any decision making? Do you still work for one of those?

While most counterproductive behavior is not tolerated in today’s workplace, a fair amount of it still exists. Management has tended to shift into a more team-building, empowering, goal-oriented style of leadership than in past years. However, there are still plenty of managers who don’t relate well to people.

Unfortunately, most of these managers stem from IT backgrounds, and they lack social skills. Or they’re traditional managers and lack IT skills. As an IT project manager, it can be tough and confusing to deal with either type.

The manager who comes from an IT background may feel threatened that new technology is coming onto the scene to replace the work and implementation they did so many years ago. Due to their current position, they’ve lost touch with the rapid pace of technology and feel frustrated by it.

Other managers who stem from traditional roles often have no grasp of technology and of what it can or cannot do. These managers often hide from decision-making responsibilities, overanalyze every phase of the project, or immerse themselves in the project in an attempt to learn as much as or more than the IT project manager.

As a project manager, you will have to find a way to deal with different types of management. Here are six types of managers you’ll likely encounter and advice on how to deal with each:

• Managers who won’t listen Managers who won’t listen are either not interested in what you are saying or have a general lack of respect for others. The best way to deal with these people is to document what you have to say. Often these managers put their confidence only in something that is in writing, as it’s on record. Use e-mail, letters, and memos to confirm conversations you’ve had with the manager.

• Managers who are aggressive Managers who yell, stomp, and are outrageously rude have become less popular in today’s workplace; however, these bullies still exist. The best way to deal with these managers is to befriend them, as much as you can, and let them know that when they act the way they do, it offends you. Don’t cower before them, and if the behavior persists, seek help from the human resources department.

• Managers who avoid decisions These managers are afraid of making the wrong decision, so they make no decision. They request more research, cancel meetings, and delay their way out of any forward progress. The best way to deal with these managers is to set deadlines with them on when the next phase of the project will commence. These deadlines don’t have to be exact dates; they can even be the accomplishment of key milestones within the project. Put the deadlines in writing and try to get a commitment from them. As an alternative, present them with the decision you suggest, and let them know if you don’t hear from them by a certain date, you will implement your recommendation. Make sure this is documented and that you give the manager a final heads-up before going ahead with your recommendation.

• Managers who micromanage These managers are typically perfectionists, feel that no one else can do the job as well as they can, or don’t trust anyone else to do the task at hand. The best way to deal with these managers is to let them know politely that they are micromanaging. They just need to be told they aren’t allowing you to do your work. Many of these managers don’t realize that they are guilty of micromanaging and need to be told to back off. Of course, you’ll then complete the task proficiently and with excellence to show the manager you can do the activity without their hovering.

• Managers who hog the credit These managers step into the spotlight as the project is created and again when the project is finished. In the meantime, their presence is not seen or heard. The best way to deal with this type of manager is to document the progress of the project publicly on an intranet site. Allow everyone to see who has done what work, when the work was completed, and how it was done. The glory-hungry manager may be there at the kickoff and at the event’s end, but their contributions aren’t recorded on the intranet site. If this solution does not work, tell the manager that they need to credit all of the team members and their hard work in the project’s success.

• Managers who rotate the discipline These managers think someone always has to be in trouble at any given time, and they will discipline someone once a week just to remind everyone else that they are in charge. Your department may refer to it as “being in the doghouse,” “called on the carpet,” or “your turn.” The best way to deal with this is to confirm the cycle of discipline and then confront the manager about it. You should always follow your organization’s human resource practices concerning confrontations in the workplace. You don’t want to create more trouble.

Working with Good Bosses

Just as plenty of bad bosses exist in the world, a large number of truly good bosses are out there. These individuals are caring, hard-working, goal-oriented individuals. They have the good of the organization in mind, know how to lead, and treat people fairly. If you are fortunate to have a good boss, let that person know that you appreciate the way they offer advice, listen to what you have to say, and treat you with respect.

Working for a good boss, however, can often be mistaken as working for a passive boss. If you can imagine another project manager working for a boss with a temper, that person’s motivation to work hard is not to get yelled at, publicly embarrassed, or put in the doghouse. On the other hand, some who have a kind boss may be tempted to become more lax because they know their manager would never yell at or embarrass them. If you have a good boss, don’t take advantage of them. Continue to work hard, to work persistently, and to lead your team.

Learn from your boss. As an IT project manager, you can learn from either type of boss that you may have. A bad manager is showing you how not to manage, while an excellent manager is showing you how it’s really done. Find the attributes of your manager that work and then repeat those skills with your project team. Not only will you become an effective manager, but you’ll also become an effective leader.

CompTIA Project+ Exam Highlight: Management Processes

There are several exam objectives covered in this chapter—and you’ll need a solid grasp of these objectives to pass your CompTIA Project+ exam. Dealing with management is an integral part of a project manager’s job, and knowing these objectives can help you become a better project manager, operate more efficiently, and boost your career. But let’s start with first things first—passing your CompTIA Project+ exam.

1.1 Explain the basic characteristics of a project and various methodologies and frameworks used in IT projects All project management approaches include a kickoff meeting to communicate the project vision and selected project framework. A kickoff meeting is a formal event for the key project stakeholders, such as the project manager, the project team, the project sponsor, and managers to walk through the project objectives, project management approach, goals, approved project scope, and project requirements. It ensures that all of the key stakeholders have a clear understanding of the project, how the project will operate, and any rules that everyone in the project must agree to abide by. Kickoff meetings aren’t opportunities to debate the project requirements, add new demands, or workshop new ideas for the project. A kickoff launches the project work based on the agreed-upon requirements.

Agile and predictive projects utilize project kickoff meetings. A project kickoff meeting communicates the effect the project will have on the organization and sets expectations for all of the stakeholders contributing to the project success.

1.9 Given a scenario, apply effective meeting management techniques Meetings are a necessity in all project management approaches, so you want to have a good grasp on meeting management techniques. This means you’ll want an agenda that maps out the intent of the meeting, a thoughtful presentation that quickly addresses the meeting purpose, and you need facilitation skills that keep the participants on track and to the timeboxed duration of the meeting. A scribe can record the minutes, notes, questions, and other details so the information, action items, and follow-up questions can be distributed to the attendees after the meeting.

1.10 Given a scenario, perform basic activities related to team and resource management A major exam objective is understanding all the organizational structures. There are three primary structures that affect the project manager. When you’re answering exam questions, pay attention to the organizational structure if possible—the structure of the organization will often affect the actions the project manager is allowed to take. Here’s a quick recap of the organizational structures:

• Functional Gives the project manager the least power and gives the functional manager the most power over project decisions. The project resides in one department or line of business, such as sales, manufacturing, or IT. Resources aren’t shared throughout the organization, and the project team members have regular operational duties in addition to their project duties. The project manager might be called a project coordinator or expeditor and must do whatever the functional manager requests on the project.

• Matrix A matrix structure uses resources from around the organization, and the project team members may be working on multiple projects at once. Matrix structures require additional communication, scheduling, and trade-offs for resources. There are three types of matrix organizations:

• Weak matrix Little authority for the project manager; functional management has the decision-making power over project decisions.

• Balanced matrix The project manager and the functional managers share project power, though there can be a power struggle over who’s in charge of project decisions.

• Strong matrix The project manager has more project authority than the functional management.

• Projectized This organization assigns a project team for the duration of the project, the project manager has total authority over the project, and communication demands are lower than in matrix structures because the team is working on one project full time.

4.1 Summarize basic environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors related to project management activities. Organizational governance describes the internal processes, policies, standards, and regulations that the project manager must follow. This exam objective can be a little tricky, as organizational governance can vary based on the project, organizational structure, and the existence of a PMO. You won’t have the same rules and processes at Company ABC as you might at Company XYZ. You’ll find, however, that certain industries use the same standards and follow the same regulations, such as in manufacturing, health care, or construction. IT project managers must be aware of the standards and regulations that affect project planning and execution for the industry in which their project resides.

Chapter Review

To begin working on a project, you need two fundamental things: dedication from you and approval from management. Often to gain the approval of management, you will have to conduct a presentation in which you sell management on the idea of implementing your business case. The business case has to be condensed into the language that all management speaks: return on investment. Once you’ve got the business case condensed, create and tailor your presentation to the audience.

Just as your opening lines on a first date are crucial, so are the opening remarks at a presentation for new technology. By starting at the end of a project and exposing what the project will deliver, you’ll capture your audience’s attention and have them clamoring for more—hopefully. Once the project has been approved, you must continue to work with management and keep them informed of the project’s progress. Management’s role in the project is that of support, not implementation.

The organizational structure will determine your level of autonomy on a project. A functional structure restricts the amount of power the project manager has. This structure assigns the power to the functional manager. The matrix structure has three levels of power for the project manager: balanced, weak, and strong. When the project manager and the functional managers work in a matrix structure, they may struggle for project power and control. The projectized environment affords the project manager the most power and authority.

At the onset of the project, you, the project manager, must bring management and your project team together. At the kickoff meeting, you’ll create a sense of camaraderie and excitement for both management and your assembled project team. Have fun! Invite management and project clients to press the flesh and snack on a donut. Create excitement to make the kickoff an event and build immediate morale. While the kickoff meeting can be an event, its purpose is to set expectations, formally authorize the project work, and explain the project goals and vision.

Project managers and the project team must follow the organizational governance for your organization and industry. Understanding how your organization does business, how the organization allows projects to move forward, and what’s expected of you as a project manager is paramount to project success. This also means the project manager must be aware of the standards, regulations, and best practices that will affect the planning and execution of the project.

Finally, as the project begins to move forward, you’ll need to work with your management. Just as there are different types of people, so are there different types of managers. Learn how to work with your manager, not for your manager. Mutual respect must be present, or the project will be grounded. No matter what type of boss you have, good or otherwise, learn from them. Mimic their good attributes and avoid their bad ones. Bosses come and go; leaders endure.

Exercises

These exercises allow you to apply the knowledge you have learned in this chapter and are followed by possible solutions.

Exercise Solutions

The following offer possible solutions for the chapter exercises.

Questions

1. You are the project manager for your organization, and you are preparing a presentation for management. This project will help your organization become more efficient, and it will help your career as a project manager in your organization. Your audience will include the CEO, customers, and end users. Considering this information, what is the most important thing in your presentation?

A. The audience

B. The message

C. The technology being presented

D. The length of the presentation

2. Marty is the project manager, though her manager calls her the project coordinator, for her organization. Her manager, Tom, meets with Marty and the project team weekly to assign project work and to review the project work completed so far. The project team members have regular operational work to do in addition to the completion of the project work. What type of an organizational structure is Marty likely a project manager for?

A. Functional

B. Weak matrix

C. Strong matrix

D. Projectized

3. Harold is the project manager for his organization. He believes that project teams can be self-led and want to accomplish the project as long as they understand the work they are to complete. Harold believes in challenging the project team and pressing their abilities to learn and do more. What management theory does Harold most likely believe in?

A. Herzberg’s theory of motivation

B. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

C. McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y

D. Vroom’s expectancy theory

4. You are the project manager for the NHQ Organization. You and several project managers have been invited to present your potential projects to a management committee to determine their worthiness, return on investment, and potential risks. What is the name of this committee that may select your project to be initiated?

A. Murder board

B. Organizational governance board

C. Technical assessment board

D. Project management office