CHAPTER 2

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: Underwriting Changes That Affect Every Potential Homeowner

WE MENTIONED BOTH Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the first chapter, but now let’s take a closer look at how both operate, what their place is in the mortgage industry, and the new lending guidelines they issue.

When lenders make a loan, they do so for a profit. They charge an interest rate at which they’ll get an annual return. For instance, if you borrowed $200,000 at 6 percent on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, the lender expects to get a rate of return of 6 percent on that loan. Easy enough.

Say, now, a lender makes not just one $200,000 loan but a hundred of them. The housing market is picking up steam, and the lender wants to make as many loans as possible to cash in on the home finance wave. That’s a lot, but this explains how lenders operate on a daily basis. A hundred $200,000 loans is $20 million. Not many lenders have that kind of money lying around, but say in this example that this one does. The lender who lends $20 million might not be satisfied with “only” lending that amount and wants to lend more. But its vaults are empty. It ran out of money. So what does it do? The lender turns to the secondary market.

In the olden days, mortgage loans (in fact, all loans), were issued based on the amount of deposits a bank or savings and loan had in their vaults. Remember the movie It’s A Wonderful Life when the Bailey Building and Loan experienced a bank run and the customers wanted all their money back? George told them they were thinking of the place all wrong. The money wasn’t in the bank—it was in their neighbors’ homes, who had borrowed their money to build and were paying it back. That’s how banks made loans; they would attract depositors by offering them a return on their money and charging a higher interest rate when they loaned that same money back out to its customers.

That’s no longer how it works with home loans. Enter the secondary market. Secondary markets are where mortgage loans are bought and sold between different banks, mortgage companies, and finally the mortgage giants Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. Ginnie Mae is the acronym for the Government National Mortgage Association and it regulates government-backed VA and FHA loans. A lender can sell a loan to another lender at a discount, replenishing its mortgage coffers with new cash so it can continue to make more mortgage loans. How can lenders do this and make a profit?

If you take a standard 30-year fixed rate mortgage at 6 percent on a $200,000 loan, the lender would make over $230,000 in interest charges over the entire term of the loan. That’s a lot of money. The problem with that scenario is that 30 years is a long time to recover $230,000. Maybe the lender can’t or doesn’t want to wait that long, so the lender sells the loan to a new lender, who will then collect the monthly interest as profit.

A typical loan sale might make $2,000 on a $200,000 transaction, surely much less than the $230,000 in unrealized interest, but the lender gets its money right away and gets its original $200,000 back to make more loans. Now multiply that amount by the 100 or so loans the lender might make every month, and that $200,000 single loan turns into 100 loans totaling $20 million. One percent of that is $200,000 in profit if all of those loans were sold.

Why would one bank want to sell loans while another bank wants to buy them? Don’t all banks react the same way to current market conditions? Generally, but at the same time, a lender might have different investment strategies than another. One bank might want to aggressively enter a mortgage market and make lots of loans and sell or keep all, none, or some of them. Another bank may want to quietly sit back and collect a safe return of 6 percent each month and make money that way. Less risk, little to no overhead, and a planned rate of return over an extended period of time. Banks simply can have different strategies just as any other type of business can. Banks can buy and sell mortgages, mortgage lenders can buy and sell, and of course so can Fannie and Freddie.

The entities buy mortgages but buy lots of them, as in trillions of dollars’ worth. When businesses sell mortgages to each other, ultimately one buyer is the last holder of the mortgage. No one else is buying. The mortgage itself could have been sold two, three, or four times over the course of a few years. When a bank has been buying mortgages over the years and suddenly wants to start making more home loans, it is caught in a predicament: Since it bought all those loans, it too is out of money to lend. So who does this last lender sell to? Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae.

These organizations were designed to provide the cash, or “liquidity” in the mortgage marketplace. If a bank wanted to sell its mortgages but no other lenders wanted to buy them, it would sell those loans to one of these three institutions. By providing this cash to banks, it creates the liquidity needed to make more home loans.

At first glance, it might seem to be an easy enough proposition to sell a mortgage from one lender to the next, but when loans are sold they aren’t “approved” all over again. If you apply for a home loan and get approved and then your lender sells your mortgage, you don’t have to go through the approval process all over again. How does the “buying” bank know what it is getting if it doesn’t examine the loan application? The selling lender guarantees, or “warrants” that the loan it is selling conforms to a predetermined set of lending criteria established by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae.

For instance, let’s look at five different loans:

- 1.30-year fixed on $200,000 at 6 percent

- 2.25-year fixed on $115,200 at 5.50 percent

- 3.15-year fixed on $400,000 at 6.25 percent with a second mortgage

- 4.30-year adjustable on $73,432 at 7 percent

- 5.15-year fixed on $328,000 at 5.75 percent

If the lender warrants that these five loans meet Fannie guidelines, then the new lender can buy those loans without having to individually approve the loans to make sure they meet lending guidelines.

LENDING GUIDELINES DEMYSTIFIED

Lending guidelines established by the secondary markets are many but the standard guidelines are as follows:

Maximum loan amount acceptable

Maximum loan amount acceptable Debt-to-income ratios

Debt-to-income ratios Sufficient funds to close the transaction

Sufficient funds to close the transaction Minimum employment for two years

Minimum employment for two years Minimum credit standards

Minimum credit standards

The buying and selling of mortgages has been streamlined to the point where mortgages are now a commodity. Even though one mortgage will seldom be exactly like the next one in terms of loan amount, credit, income, and so on, they are all alike because they fit the guidelines established by the secondary markets. Now these loans can be bought individually, called “flow” selling, or in big chunks where loans are packaged together, called “bulk” sales.

The secondary markets couldn’t function as they do if each and every loan had to be scrutinized; there simply wouldn’t be enough time to make the effort worthwhile. That would mean a lender would have to be very, very certain it not only wants to make that loan but also ties up its money for long periods of time.

If a mortgage loan is not a commodity that can be bought and sold quickly, there would be higher rates across the board for everyone. If, indeed, a product is a commodity, then lenders can compete against one another on the exact same product. Lenders would offer both a competitive rate and lower closing costs if they had to fight over the very same loan—much like any other business that bought and sold goods or services. If loans were all different, it would be impossible to evaluate them all.

Further, if loans couldn’t be easily sold in the secondary markets, rates would be higher across the board, because a lender would be committed to tying up its money over the long haul—money it could invest in other categories when markets change. If, for example, a mortgage is made at 6 percent on a 30-year loan, that would tie up that money for 30 years or until the note was retired (if the owner sells the home or pays off the mortgage sooner).

Suppose the lender makes the decision and issues money at 6 percent for 30 years, but six months later the economy changes and lenders are issuing mortgage rates at 8 percent! Because the lender can’t sell the mortgage, the lender is losing money every day—it could be making 2 percent more on its loans but can’t because it is tied up in a 6 percent loan.

To offset such a scenario, a lender would price its mortgages artificially higher at the beginning to offset any potential increase in mortgages down the road. Or worse, not issue any fixed-rate mortgages whatsoever and only issue adjustable-rate mortgages. Adjustablerate mortgages, or ARMs, can move up as interest rate markets move up. The predictability of a fixed-rate loan would no longer exist. Lenders would be forced to either price their mortgage higher or not issue fixed rates at all. We’ll discuss how to pick the best mortgage loan in Chapter 6.

UNDERSTANDING CONVENTIONAL AND GOVERNMENT LOANS

Loans underwritten to Fannie and Freddie guidelines are called “conventional” loans, and loans underwritten to Ginnie Mae standards—VA, FHA, and USDA loans—are called “government” loans. Conventional loans can be “conforming” or “nonconforming.” Conforming loans mean the loan itself does not exceed a specific amount, while nonconforming loans, called “jumbo” loans, are loans that are above conforming loan limits. Government loans can also have two categories of loans.

The difference between the two mortgage types, conventional and government, lies in who actually guarantees or warrants the mortgage loan. Individual lenders warrant conventional loans, while the federal government guarantees government loans. If a conventional loan goes into default, meaning the loan went bad and is either in foreclosure or otherwise foreclosed on, it’s the individual lender who takes the hit. That means the lender has to write off or write down the value of that asset.

With a government loan, the government guarantees the performance of the note. As long as a lender issues the government loan in accordance with VA, FHA, or USDA guidelines, the government compensates the lender by buying that loan, taking it off the lender’s books.

What if a lender buys a conventional loan and it goes into default? As long as the loan was underwritten per conventional guidelines, then the buying lender can do nothing. But, if the loan was found to not have been underwritten in accordance with conventional guidelines, the original lender will “repurchase” the bad loan due to a buying/selling contract between the two lenders. For instance, a loan might have been approved that required the buyer to have been self-employed for at least two years but the lender made a mistake and approved the loan without verification of two years of self-employment, typically evidenced by two years filed tax returns. Or a loan could require that the buyer put down 5 percent of his own funds in the transaction, but it was later discovered that the buyer borrowed the money from a friend and pretended the money was his.

In either instance, due to an underwriting mistake by the lender or fraud by the borrower, the unfortunate lender would be forced to buy that loan back with funds it no longer had because it used the funds from selling the first mortgage to issue another.

If a few of these scenarios occur, the lender is no longer in business.

When a government loan is foreclosed on, the government guarantees that note and typically sells the property at an auction or through prearranged sales. If you’ve ever heard of the term “HUD foreclosure sale” then you’ve just heard how the government can get its money back when it is forced to reimburse a lender for a loan that went bad. Of course, if there was fraud involved or the lender made an underwriting mistake, then the lender might still be forced to buy back the offending loan.

As discussed in Chapter 1, mortgage loan guidelines have changed over the years and now look totally different than they did just a short time ago. What has changed, and how do you qualify with these new changes?

CHANGES TO THE MAXIMUM LOAN AMOUNT

The current maximum conforming loan amount is at $417,000. In fact, it’s been at that level for more than three years. What makes this unique is how loan limits are established and what constitutes a conforming and a jumbo loan.

Historically, in each October of every year, the Office of Housing and Economic Development would calculate the current, average home price in the United States and compare it to the previous year. If the home price increased by 8 percent over the previous year, then the maximum conforming loan amount would be increased by 8 percent.

This happened year after year, every year. Interestingly enough, home prices typically showed some type of increase the previous year. Therefore, the loan limits were increased. Then in the late 2000s, home prices started to decline. This happened as the housing bubble was just about to burst. The loan limits looked as if they’d actually be lowered instead of being increased or held steady. If loan limits dropped, that would put more people out of buying a home, slowing an already-damaged housing market. Instead of decreasing the loan limits, the government left maximum conforming limits the same, where they are today.

SUPER-CONFORMING LOANS

The next question is how high jumbo mortgages can go that can still be considered conventional, or loans that can be bought or sold by banks or Fannie and Freddie.

This is also a major change. Historically, jumbo mortgages meant anything above the current conforming limit. Now, however, jumbo carries a new moniker- “super-conforming.”

Super-conforming means the loan amount is above the conforming limit yet still available for purchase and sale in the secondary market. In the past, private agencies were established that bought and sold jumbo loans in the secondary market, but these went away in 2007.

These private agencies performed the same functions as Fannie and Freddie did, and with them came some very affordable interest rates—typically, only about 0.25 percent higher than a conforming loan. If a rate for a $300,000 loan could be had on the open market for 6.00 percent, then a loan in the amount of $500,000 could be found for, say, 6.25 percent. But that tiny spread soon died with the demise of the private secondary market for jumbo mortgages.

This created a void in the jumbo market, temporarily halting jumbo activity. Soon thereafter, Fannie and Freddie both entered the jumbo market by buying loans above the $417,000 conforming limit.

Because of their entry in the jumbo market, the buying and selling of jumbo loans could occur again, with the new limits set at $625,500 if you lived in a high-cost area. High cost is determined by multiplying the median sales price of homes in your area by 1.25. If that number exceeds $417,000 then you qualify for the conventional jumbo loan up to $625,500.

But now the differences between a conforming rate and a jumbo rate are closer to a full percentage point instead of a quarter percent. If you can find a conforming rate at 6.00 percent then that same lender could offer a jumbo loan at 7.00 percent.

That means if you bought a home for $500,000 and had only 10 percent down, your loan amount would be $450,000, requiring an increase in interest rate by a full percentage point, even though the conforming loan amount was just about $30,000 less than the amount you’re borrowing.

There are ways to overcome this issue, as we’ll discuss in detail in Chapter 6, but as you can see, these changes have affected homes in higher priced areas much more so than others.

CHANGES TO CREDIT SCORE UNDERWRITING

You’ve heard about them. In fact if you turn on the television, the radio, or peruse the Internet you’re likely to witness at least one advertisement talking about credit and credit scores.

Exactly what are credit scores? Scores are a numerical value placed on the likelihood of someone defaulting on a loan. The lower the score, the greater the likelihood of default. Default can mean making a payment more than 30 days past the due date of the bill or not paying at all.

Credit scoring really hit the mortgage scene in the late 1990s, when they were used as an additional risk-evaluation tool. In fact, up until 2008, minimum credit scores weren’t required for most conventional and government loans. As long as a loan was approved with an automated underwriting system, or AUS, the credit score mattered little. Nothing, in some instance. We’ll examine the AUS in more detail in Chapter 4.

But how are credit scores calculated? Do employees at the credit bureau look at your credit report and assign a number? Not exactly, but your credit score will reflect previous payment patterns.

The credit score used by mortgage lenders was developed by a company called Fair Isaac Corporation, or FICO. All three credit bureaus (Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion) use the FICO scoring model. Your credit history assigns a certain number of “points” that make up your credit score. Or more correctly, it deducts points from your total number of available points for cracks in your credit. Credit scores can range from a low of 350 (I’ve never seen one that low) to 850 (I’ve never seen one that high, either). Perfect credit is 850. As different business and other companies that have issued credit to you report your payment patterns, your credit score will emerge.

So if there are three credit bureaus, Equifax, Experian, and Trans-Union, are your credit scores all the same? That’s highly unlikely, and here’s why. These three bureaus are nothing more than repositories—they’re holders of data. When a business opens up a credit account for a borrower, the business reports various things about the credit account to the bureau. How much you borrowed, how much your payments were, if you were ever late and by how much, and so on. In exchange for reporting this information to the credit bureau, the business can also pull credit histories on its potential customers to see how they paid in the past with other businesses.

IMPROVING YOUR CREDIT SCORE

Credit scores comprise five major components, each with its own weight.

35 percent of your score is made up of your payment patterns.

30 percent of your score is made up of your available credit.

15 percent of your score is made up of how long you’ve had credit.

10 percent of your score is made up of credit inquiries.

10 percent of your score is made up of the types of credit accounts.

You start with the potential of 850, and then the points start coming off. Here are some ways you can improve your credit score.

Improve Your Payment Patterns

This is the easiest to understand; it simply means paying on time. Technically, it means not being more than 30 days late. Being more than 30 days past your due date will immediately harm your score, and points will be deducted.

Being more than 60 days late hurts even more than a 30-day late payment. And 90 days? Worse still. When loans get past 90 days late, they can be “charged off ” by the original creditor, deeming the account no longer collectable. That’s how a credit bureau reports your payments, in terms of 30-day increments. By keeping a history of not having late payments over time, your credit scores will rise.

One important note: Credit accounts can have penalties when a payment is not made on or before the due date. Even if you haven’t made a payment 30 days past the due date, while that information won’t be reported negatively to the credit bureaus as a late payment, indeed the creditor will regard a payment made past the due date as a negative and charge you higher rates, fees, or both. So to the best of your ability, pay your bills on time. They will affect your mortgage.

Control Your Available Credit to the Secret Ratio

The second most important score component is that of available credit. Put another way, how much are your current loan balances compared to your credit lines available to you?

For instance, if you have a credit card with a limit of $10,000 and a $5,000 balance, your available credit is 50 percent. If you have a $3,000 balance, then your available credit is 70 percent of your limit. It then follows that a zero balance gives you a 100 percent available.

But within all these percentages lies a secret ratio, 33 percent. By keeping your current credit balances at or around approximately onethird of your available credit, your credit scores will improve. As your balances grow and approach your credit limits, your scores will begin to deteriorate.

Let’s say your current balance is $3,000 and your credit card limit is at $10,000. Your credit scores will constantly rise over time. The longer you keep your balances at or around one-third of your limits, the better your scores will be.

Then you decide to take a vacation, but instead of paying cash for it or putting it on your debit card, you elect to pay for it on your credit card that has the $10,000 credit limit. The vacation costs $5,000 and you put that $5,000 on your card. Add that $5,000 to the $3,000 balance you already had, and your new balance is $8,000, or 80 percent of your available credit. If you paid off that balance before you got your next statement, your scores might not take a hit, but if your new 80 percent balance is reported to the three credit bureaus, then your credit scores will drop. Worse still, should you not only approach 100 percent of your available credit but also go over your limits, your scores will be harmed further still.

What happens to your scores if you pay your balances off completely instead of keeping a balance? Oddly, your scores will drop instead of rise. It sounds odd at first glance, but if you think about it for a moment, it does make sense.

Remember that scores are an indicator of a possible loan default, and how would a lender know if you were likely to repay a debt if there were no debt to pay off? In other words, can you not only be approved for credit but be able to pay that debt back when due? Would you make your payments before the due date? After the due date? Would you pay the minimum, or would you pay the balances off entirely?

If you never charged anything or never used credit, then you haven’t shown, at least to the credit bureaus, that you can responsibly handle credit accounts.

Think Before You Close an Account

Closing accounts can also harm your credit score. That’s right, what might seem to be a responsible move at first glance can actually lower your score. Let’s look at that magical percentage again of 33 percent.

If your credit limit is at $10,000 and you’ve had this account for a while, then your scores will begin to reflect that account history. If you’ve charged some things then responsibly paid them back over time, then your scores will improve. But if you paid off that balance and then canceled that account, suddenly you don’t have the credit limit anymore.

Your available credit, which ideally should be around 33 percent, is now at 100 percent—exactly the same percentage as if you charged up your credit card to the $10,000 limit. Your credit limit is zero and your balance is zero.

Your scores will drop in this example. I know that old school thinking, and I think I would agree, is to close old accounts you no longer use. That makes sense to me for a variety of reasons, one of which is to limit the possibility of identity theft. But closing unused accounts will drop scores.

This quirk comes into play in a different way when we look at another example.

Let’s say we have three credit cards with a $10,000 total credit line, with each card carrying a $3,333 limit. If the total balance is $3,000, then the balances are at 30 percent of your available credit. That’s good.

Now close one of those accounts by transferring the balance to another card that might have a lower interest rate. So you transfer a balance and close out one of those cards and you still have a $3,000 balance, but by closing one account you’ve lowered your credit limit from $10,000 to $6,666.

By comparing your balance, which remained constant, with your new, lower credit limit, that percentage works to 45, which is a $3,333 balance and a $6,666 limit. Your scores will begin to drop as your balances approach half of your credit limit when all you did was take a prudent move and transfer a balance with a higher rate to another card and close the old account.

Now take that one step further and close one more account, leaving you with a $3,333 balance and a $3,000 limit. Your scores will take a huge negative hit because not only did your available credit disappear, but you also exceeded your limits.

There were recent changes in this formula that caused FICO to adjust its algorithms. It became evident that the more available credit one had when compared to the balances, as long as those balances were at 33 percent of available credit, the scores would increase. So someone found out that an “authorized user” of a credit card could take advantage of the credit history of the account they were authorized on.

An authorized user is someone who isn’t ultimately responsible for paying the credit card debt but has the authority to charge things on the card. This is common, for instance, with a college student who has a credit card with her name on it but the account really belongs to her parents. The daughter who had no established credit or poor credit scores could increase her scores by “borrowing” her parents credit history by being added as an authorized user.

If you pay attention to your payment history and your available credit, you’ll have mastered your credit scores.

Rely on Length of Credit History

The length of credit history represents 15 percent of your score. The longer you’ve had credit accounts that have reported to the credit bureaus, the better your credit score will be. Even if you’ve had some late payments in the past or had your available credit lines reduced, the longer-term impact of other negative credit items will be lessened.

Limit Credit Inquiries

A credit inquiry means some other company has looked at your credit report either with or without your express permission. A common example of a permitted credit inquiry, an inquiry with your permission, is when you might apply for an automobile loan. You shop for a car, then apply for a car loan. Or you do that in reverse—either way, you give a business your permission to review your credit history.

Each time a business reviews your credit in order to make a credit decision that you requested, it will lower your credit score. Multiple credit inquiries could be an indicator that someone is in or soon will be in financial straits.

There are some consumer protection features that help protect your credit score if you apply for credit in multiple places if your credit request is for the same transaction and within a relatively narrow period of time.

Say you’re shopping for a new boat and you want to finance it. You go to the boat store and you apply for credit there. You call your credit union that same day and apply for credit there, as well. In this example, there would only be one credit inquiry and it would not be counted as multiple ones, which would drive down your score.

However, if you applied for a boat loan at the boat store, thought about it for a few weeks and then called your credit union again and applied for credit once more, then you can expect your scores to fall.

The same thing can happen when applying for a mortgage with multiple lenders. As long as your inquiries are within a relatively short time frame, typically within 30 days, then the scoring models will consider that as a single inquiry because it’s for a single transaction. If you applied for a mortgage to buy a home, then six months later decided to refinance, that would be considered multiple transactions and again drop your scores. There are credit inquiries that don’t affect your credit score at all; these are called “soft” inquiries.

The most common soft inquiry is when a consumer checks his own credit to review for any errors or to simply get an update on what his credit report looks like. When a consumer checks his own credit it’s not considered a “hard” inquiry that would indicate someone was applying for more credit.

Another example of a soft inquiry is when an employer might check someone’s credit as part of its hiring process. Or a credit card company that is expanding its customer base would access a consumer’s credit report to decide whether to offer a new credit card. Both of these instances are considered soft and won’t affect a credit score one way or another.

Pay attention to when you have credit inquiries made. If they are made close together and for the same purpose, you likely won’t get hit.

Recognize That Different Types of Credit Can Hurt or Help

There are different types of credit issued, based on what is being collateralized (if anything) and the type of company issuing the credit. A bank issuing a mortgage is considered the top-tier credit account both because it’s for a mortgage and not a boat, for instance, and also because it’s made from a retail lending institution that offers credit cards, checking accounts, and savings accounts primarily to those with good credit.

Another top-tier credit account would be an automobile loan or some other tangible or secured asset.

Credit cards can positively impact a credit account as long as they’re also issued by lenders who primarily make loans to those with good credit. For those with not-so-good credit, there are finance companies that make loans to those with either less than perfect credit or no credit at all. Although a credit score can benefit with a positive payment history on a loan obtained through a finance company, it won’t be impacted as much if the same credit line were issued by a bank or credit union.

Finally, there is one other type of credit: alternative credit.

Use Alternative Credit

Alternative credit accounts have changed over the years and can now be part of a credit report just as any other trade line. Alternative credit is made up of things such as paying rent on time, or paying a cell phone or cable TV bill on time, each and every month.

Cable TV companies and cell phone companies, just like other utility accounts such as electricity, water, and telephone, don’t report consumers’ payment history to the credit bureaus. There are no 30-, 60-, or 90-day late payments that would show up on your credit report in the same way as an automobile loan would. Their emergence as a legitimate credit source, however, has helped consumers become homeowners who hadn’t established a traditional credit history with credit cards or automobile loans.

So who would use alternative credit? There are two types: those who haven’t yet established credit in the traditional fashion and those who refuse to use credit cards and only use their debit cards or cash/emergency funds.

NEW UNDERWRITING REQUIREMENTS REGARDING CREDIT

It is important for you to be able to provide appropriate credit history because recent changes in Fannie and Freddie guidelines now make it a requirement that at least three trade lines plus rent be reflected on a credit report with activity in the last 12 months.

In the past, consumers would only need to provide 12 months of canceled checks along with their pay history from say, their cable bill, and then a person at the mortgage company would verify the information and include that documentation in the loan application package. There was no need to report it to the credit bureau. And even if there were, it was a tedious process for the credit bureau to enter the information manually onto the credit report. This is no longer true.

GETTING ALTERNATIVE CREDIT ON YOUR CREDIT REPORT

The process of getting alternative credit on your credit report is relatively easy, although not as easy as simply pulling a credit report. Instead, the consumer gives the lender the contact information for a landlord, the electricity, phone, and water companies, or other monthly obligations that are provided by third parties. Cell phone bills, Internet access, insurance payments—it could include anything that is paid to a third party on a monthly basis that can be independently verified.

The lender contacts the phone company and asks for a 12-month payment history. The phone company provides that payment history and shows how many, if any, monthly payments have been more than 30 days past their due date.

The lender collects the three accounts plus the landlord information and forwards it to the credit bureaus, which enter the information on the credit report. Now the credit report accurately reflects the alternative credit while at the same time complying with lender requirements of having a credit report containing three trade lines plus rent over the previous 12 months.

ESTABLISHING APPROPRIATE ACCOUNTS (AND A SECRET ALTERNATIVE IF YOU DON’T)

What if a borrower doesn’t have three accounts in addition to rent? What if the borrower only has two accounts, such as rent and a cell phone? This is common for someone who lives in an apartment building with most or all of the utilities included in the rent.

In this example, there really is no way around the minimum accounts required by mortgage companies. The borrower must establish new accounts for a 12-month period. This can also affect those who live with their parents or otherwise rent-free.

There is one other type of account that can work, but you’ll need to check with your potential lender ahead of time, because not all lenders accept this account: regular savings. A regular savings account, or other type of investment account, can work as an alternate credit type under certain conditions:

The payments must be made at least once every 90 days.

The payments must be made at least once every 90 days. The account may not have any withdrawals over the previous 12 months.

The account may not have any withdrawals over the previous 12 months. The amounts must be regular, significant amounts.

The amounts must be regular, significant amounts. The account must be voluntary and not forced.

The account must be voluntary and not forced.

Most such accounts are savings plans that take out a certain amount of money each month from a checking account and transfer it to a savings account. The account must also grow and not be depleted. Depositing money and then withdrawing it doesn’t show any diligent pay history to that account.

The payments must be regular in nature—meaning once per month, every month, or once per quarter—and also be “significant” in nature, meaning that someone who makes $5,000 per month won’t get too much credit for a $5 per month savings plan.

Finally, the payment must be voluntary and not forced. An example of a forced payment is a regular monthly contribution to a 401(k) plan, where the funds are deposited directly into a 401(k) account instead of given to the consumer who then deposits those funds into a savings account.

Someone with an active 401(k) account can’t suddenly start and stop their contributions at will; it’s not voluntary in that manner. Employees can certainly change their contributions when they’re told they are able to by their employer, but this isn’t considered voluntary.

But if you don’t have an active, voluntary, regular savings account with no withdrawals for the past 12 months, you’ll need to start one if you need an additional alternative account.

CHANGES TO UNDERWRITING IN REGARD TO CREDIT SCORES

If you’re about to apply for a credit card, the credit company won’t make a bunch of phone calls to people and businesses that you have credit with but will instead contact one or more of the credit bureaus to see how you paid those accounts in the past. This is done electronically by providing the business with a number, your credit score.

These three bureaus are located in different parts of the country. Some businesses subscribe to all three bureaus and some to just one. It costs a business money to subscribe to each individual bureau, and sometimes these businesses don’t feel the need to check with all three bureaus that are geographically scattered across the United States but, rather, trust that if you’ve got good credit at one bureau, then the likelihood of you having good credit at the other bureaus is high.

If a business only uses one bureau, then that bureau will be the only repository to receive credit histories from that business. A business may use Experian but not TransUnion, for example, on a regular basis. As credit histories mature and credit scores begin to form, the different bureaus will most likely have different scores—similar scores, but different nonetheless. Mortgage companies use all three credit bureaus when making a mortgage decision, and the scores might look something like this:

| Experian | 726 |

| Equifax | 699 |

| TransUnion | 719 |

Even though all three use the same FICO scoring engine to create these scores, because they all contain slightly different credit information, the credit number will be different.

A lender will throw out the highest number and the lowest number and use the middle one. In this example, the score from Trans-Union at 719 will be the score used for the mortgage credit decision.

Now let’s look at a couple borrowing together.

| Credit Bureau | Borrower A | Borrower B |

| Experian | 726 | 675 |

| Equifax | 699 | 618 |

| TransUnion | 719 | 602 |

If there are two people on the same loan, which credit score does the lender use? It used to be that the lender would use the middle credit score of the “breadwinner” or the person who made the most money in the household. This is no longer true. Now a lender uses the borrower with the lowest aggregate credit scores and uses the middle score. Sometimes this can cause a loan to be denied due to damaged credit or could perhaps penalize the applicants with a higher rate, fees, or both. We’ll examine how to overcome this particular obstacle in Chapter 8.

REPAIRING YOUR CREDIT SCORE

Although credit scores have always been important, they have never become more so since lending guidelines changed in 2008. Now credit scores can directly impact your mortgage rate.

In the past, there was no such thing as a minimum credit score as long as one got an approval using an automated underwriting system. Not only that, but someone with a lower score could get the very same interest rate as someone with a near-perfect credit score. For instance, an automated underwriting approval would take into consideration a variety of factors such as debt-to-income ratios, equity in the property, assets, and any number of things that would come to make a financial portfolio of a mortgage applicant.

How can a borrower with a 580 credit score get the very same interest rate as someone with an 800 score? It does seem a bit illogical to have credit scores in the first place if it has no impact on the mortgage rate.

If, however, there were other compensating factors that played into the approval equation, that could mean someone with a 580 score could get a 6.00 percent rate, the very same rate an 800 score borrower could get. If the 580 borrower had tons of equity in his house, it would offset the lower credit score. For example, if the house appraised at $500,000 and the loan amount was only $100,000, a borrower would be less likely to default on a mortgage by giving up all that equity through foreclosure. This is the reasoning, anyway.

If, by contrast, that same borrower with a 580 credit score tried to borrow $450,000 on a $500,000 home, then the loan would typically be declined with an automated underwriting system.

THE NEW MODEL FOR QUALIFYING: THE LOAN LEVEL PRICING ADJUSTMENT (LLPA)

For nearly a decade, credit scores had little impact on a loan approval other than being an indicator of the likelihood of default. But that changed. Now lenders use a model designed by Fannie and Freddie called the loan level pricing adjustment, or LLPA. Bye-bye, zero-down mortgage!

Established in December 2008, the LLPA is a complicated yet strict guideline that, for the first time, combines a credit score with an equity position to determine not simply a loan approval (the automated underwriting system does that), but to determine the interest rate issued for that loan as well.

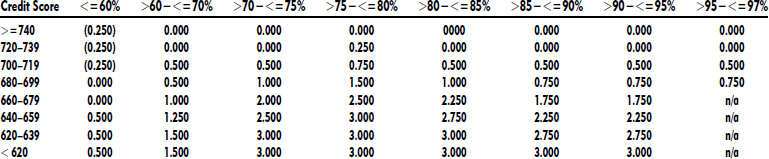

The LLPA is fluid and can change based on how current credit markets are behaving. In good economic times, the LLPA grid can be relaxed, and in more difficult economic times, the grid will be more restrictive. The chart on the facing page is a typical LLPA grid.

Confusing? Of course it is, at first glance. This is the chart lenders use to adjust your interest rate, depending on a combination of credit scores and your down payment, or equity, position. There are two charts here, one for a standard mortgage and one for a mortgage refinance loan that pulls equity out of the property.

Cash Out Refinance Adjustments (in addition to adjustments above; does apply to 15 yr terms)

To use the chart, first find your credit score. Then find where it would fit in the very first column on the left-hand side titled “Credit Score.” Next review the following columns that are headed < = 60%, >60% < 70%, . . . and so on. These columns express your loan amount compared to the value of the property, or LTV, which means loan to value.

On the very far right, you’ll see >95%< = 97%. This means the loan amount is at or above 95 percent of the value of the home but less than or equal to 97 percent of the value of the home.

If the value of the home is $100,000 and your loan amount was $96,000, then this would be your column. Next, find your credit score and match it up on the far-left-hand column. Find your score, then move over to the right for the appropriate LTV.

If your credit score is 681, your loan amount is $96,000 and your value is $100,000 then your rate adjustment is 0.75 points. Stay with me here.

Let’s say you have a credit score of 724 and you have 25 percent down. Then find your appropriate credit score row then move over to the column labeled >70%< = 75%. You’ll notice the adjustment is 0.00, or zero adjustment to the rate.

The impact of the LLPA is this: If you have no rate adjustments according to the LLPA and the going market rate for a 30-year mortgage is 6.00 percent at zero points, then that’s your rate, according to the LLPA matrix.

If, however, your loan amount is at 96 LTV and your credit score is 681, then your rate would be 6.00 percent with an additional 0.75 points. One point equals 1 percent of your loan amount, so in this example your additional fees in the form of points is 0.75 percent of $96,000, or $720

Now let’s take it one step further and say your loan amount is $96,000 but your credit score is 679. When you find your credit score in the appropriate row, then follow all the way across to the >95%< = 97% column. You’ll see no adjustments at all. Nothing but a line where the adjustment is supposed to be.

|

If there is a line and no adjustment, that means you can’t get approved with your current credit score and down payment. |

|---|

IMPORTANCE OF CREDIT SCORES

This is the first time that credit scores have been used to decline a loan application. But not to fret, it may not be the end of the road. With your credit score of 679, you’ll notice that if you travel one column to the left, you’ll see an adjustment of 1.75, or 1.75 points. And by moving over one column, you’ll also see that your LTV limits have fallen to > 90% < = 95%.

Now you can get your approval but you had to bring your loan amount equal to or below 95 percent of the property value and pay 1.75 points. On $95,000 you would get a 6.00 percent rate and pay 1.75 points, or $1,662.50.

We’ll examine how rates are set and closing fees in detail in Chapter 8, but as you can see, the more risk the lender takes on in terms of credit and equity, the more the borrower will have to pay. This is for owner-occupied properties only.

CRITERIA FOR INVESTMENT PROPERTIES

Investment, or rental, properties are considered higher risk than a property that is occupied by the borrower. The reason is obvious in that, should a borrower who owns more than one property—his primary residence and some rental houses—ever fall into financial straits and has problems paying his mortgages then it’s the primary residence that will be paid first. An investor will let rental properties be foreclosed on before he’ll allow his primary residence to go.

Investment properties will also be priced with the LLPA but also add another fee, that for the property being an investment property versus a primary residence. Investment properties also require more down, as there is no such thing as a 3 percent down investment property mortgage. Conventional investor loans require a minimum of 20 percent down. In a purchase transaction with 20 percent down, the lender will add 2.25 points, or $2,250 on a $100,000 loan.

To see how the LLPA affects investment loans, first use the LLPA grid and take the credit score then find the appropriate LTV column. If the credit score is 655 with 20 percent down the adjustment would be 3.00 points for the score/LTV adjustment then add another 2.25 for putting down only 20 percent. That’s a total of 5.25 points, or $5,250 in additional fees.

Using that very same scenario but with a 750 credit score, the adjustments would be 0.00 adjustment for credit score and 2.25 for 20 percent down. If the borrower puts 25 percent down instead of 20, the adjustments would again be 0.00 for the score and then 1.75 points for 25 percent down.

That’s for a single-family residence. For a duplex or a two- to four-unit complex, there is an additional adjustment still. There is another 1.5 points added to the transaction.

This is the new world of mortgage pricing, and it can get confusing, even for the loan officer. If you’ve got a “technical” mortgage, which means that you’ve got an average credit score with minimal down and it’s an investment property, make absolutely certain your loan officer is getting the numbers straight. You don’t want to go down the merry little road and suddenly find out that you’re required to pay an additional $2,000 the loan officer forgot to quote you. We’ll discuss closing costs and disclosure requirements in detail in Chapter 8.

NEW RULES FOR REAL ESTATE INVESTORS

Fannie and Freddie both have new underwriting guidelines for investment properties, and it determines how many mortgages a person is allowed to have and still get a conventional loan.

In the past this has been a moving target, but both agencies have limited the number of financed properties a borrower might own. This has varied from as few as four properties to as many as ten, but the new guidelines spell out the requirements for both.

First, note that the guidelines are for financed properties— properties with loans against them. If the rule is that you can have only 10 financed properties, that doesn’t mean you can’t own 100 properties. You can. You just have to make sure that only 10 of them have loans on them and the others are free and clear.

The rules depend on how many financed properties you own. There are two new guidelines here that apply to someone with 1 to 4 financed properties then another set of rules for those with 5 to 10 financed properties.

Anyone can finance up to four properties with few restrictions, other than the requirement that the owner can qualify based on credit and income. A common question for the novice real estate investor is, “Can I use the rental income from the property I’m about to buy to help me qualify for a loan?” The answer depends on whether the borrower is an experienced real estate investor or has rental properties that he collects rent and pays mortgages on. In the case of a new investor who only owns his own home and the mortgage that goes along with it and then decides to buy a rental property, a lender will not allow the borrower to use the rental income to help him qualify. There is no history of being a landlord and managing the real estate asset.

Say the rental property yields $2,000 per month in rent and the new mortgage payment would only be $500. Then that would leave $1,500 per month in additional income. But if the borrower needs that additional $1,500 per month in income in order to qualify for the new loan, without having been a seasoned real estate investor, the lender won’t allow that income to help qualify for the new loan.

By contrast, if someone has owned rental properties or currently owns them, then the lender would use that additional income to be realized from the new investment real estate in order to help qualify the borrower if that income is needed.

How would a lender know that one way or another? The lender will ask for tax returns and look for what is called the IRS Schedule E, which shows real estate transactions for that tax year. When someone owns rental properties, the rental income and expenses are reported on the Schedule E portion of their tax return. A lender won’t simply take someone’s word for it.

These changes have turned the conventional underwriting world upside down, as lenders tightened their lending guidelines and Fannie and Freddie both have been overhauled in every aspect of their mortgage lending, from the maximum loan amounts to minimum down payment requirements.

SUMMARY

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac provide liquidity in the mortgage marketplace. Lenders must conform to their guidelines if they want to continue making mortgage loans. These loans are called conventional.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac provide liquidity in the mortgage marketplace. Lenders must conform to their guidelines if they want to continue making mortgage loans. These loans are called conventional. Guidelines place limits on maximum loan amounts, debt-toincome ratios, sufficient funds to close, and minimum employment and credit standards.

Guidelines place limits on maximum loan amounts, debt-toincome ratios, sufficient funds to close, and minimum employment and credit standards. Jumbo rates have risen dramatically compared to conventional conforming loans.

Jumbo rates have risen dramatically compared to conventional conforming loans. For the first time, credit scores are required for a conventional mortgage.

For the first time, credit scores are required for a conventional mortgage. Credit scores are calculated using payment history, available credit, length of credit history, credit inquiries, and types of credit used.

Credit scores are calculated using payment history, available credit, length of credit history, credit inquiries, and types of credit used. There are legitimate tricks to improve your score.

There are legitimate tricks to improve your score. Alternative credit can be added to a credit report.

Alternative credit can be added to a credit report. Lenders pull credit scores from the three bureaus and use the middle score.

Lenders pull credit scores from the three bureaus and use the middle score. LLPA is a significant change to the industry and combines credit scores with equity position to price a rate for a borrower.

LLPA is a significant change to the industry and combines credit scores with equity position to price a rate for a borrower. Limits are placed on real estate investors.

Limits are placed on real estate investors.