11. Developing Sustainable Business Models

Nabil Harfoush is the Director of Strategic Innovation Lab at OCAD University in Toronto and Assistant Professor in the Strategic Foresight & Innovation Masters Program. He leads a research group on Strongly Sustainable Business Models. He is a Fellow at Philadelphia University, where he teaches Business Model Innovation. Nabil has over 40 years of experience as engineer, executive, entrepreneur, and educator. He has consulted for enterprises, governments, the World Bank, W.H.O., UNESCO, and IDRC and has served as CIO of several technology companies. Nabil has a master’s in computer engineering and a Ph.D. summa cum laude in digital data communications from Germany.

What Is a Business Model?

Much has been written about business models in recent years, but the term “business model” is relatively recent in business language. It hardly appeared in print before the late 1990s.1 Since then, it has moved from being a novel, intangible concept to something more concrete and has rapidly occupied a place in management language that is at least as prominent as the traditional terms of business plan and business strategy.

So what is a business model? As to be expected, there are many definitions of what a business model is, and they tend to vary depending on the line of business discussing it: sales, marketing, operations, research and development (R&D), and so on. But when the various lines of business have to collaborate on creating new business models or even to discuss the current business model of their organization, these many definitions and frameworks collide. The result is an inefficient process for business model innovation in an era when speed of innovation is key to the survival of the enterprise.

In the previous chapter D. R. Widder introduced the definition prevalent in business model professionals’ circles: A business model is a description of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. Let’s consider the case of an invention that is patentable. Registering the patent creates value, but as long as the patent is not converted into real applications it does not deliver value; and only when the patent generates revenues for the organization does it capture the value created and delivered. A charitable organization, on the other hand, creates value (social or financial) and delivers it to people who need it, but does not capture that value for itself and therefore usually remains dependent on external donations and hence financially is not sustainable.

The Business Model Canvas

Chapter 10, “Value Creation through Shaping Opportunity—The Business Model,” also introduced the Business Model Canvas framework proposed by Alex Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur in their best-selling book Business Model Generation.2 The Canvas provides a simple visual tool that captures the nine essential elements describing any business model:

1. The value propositions at the core of the business model

2. The customer segments targeted by these value propositions

3. The channels through which the value proposition is delivered to customers

4. The type of customer relationships necessary to successfully deliver the value proposition

5. The revenue streams resulting from the delivery of the value propositions

6. Key activities necessary for the business model

7. Key resources needed for the key activities to occur

8. Key alliances and partnerships enabling the organization to deliver its value proposition more efficiently

9. The cost structure resulting from elements 6–8

The first five elements form the right side of the Canvas (see Figure 10.3) and describe the essence of the business model in terms of value proposition and desired delivery. The left side consists of all the cost elements needed to deliver the proposed business model.

The visual aspect of the Business Model Canvas has an importance that is frequently underestimated. The visual nature of the Canvas and its nine elements presents a common framework to the various lines of business simultaneously. It has proven in practice to be an excellent tool for overcoming the different frameworks and vocabularies used by the various lines of business when considering business models and for emerging a common vocabulary and mental model about the enterprise’s business model among the lines of business involved. It thus leads rapidly to a shared understanding of the organization’s current business model and potential alternatives and thus improves the efficiency of the enterprise’s innovation processes not only in the business model area but also across the lines of business of the organization.

Incidentally, a similar challenge arises in multidisciplinary teams working on solving a complex problem. Here, too, the visual aspect of the Canvas can provide an effective tool to accelerate the common understanding by team members of the different aspects of the problem at hand as well as on the perspectives, methods, and tools available from the various disciplines to address that complex challenge.

Better business modeling tools also play an important role in the overall efficiency of investments made in the company’s innovation activities. Developing a detailed business plan is usually a labor-intensive and time-consuming process. Consequently, business plans tended traditionally to be developed for one set of value propositions and customer segments, usually not straying too far from the previous set. Developing and evaluating several business models, on the other hand, enables the exploration of multiple alternative models, each investigating a different set of the nine elements and identifying the few promising combinations, for which then the substantial time and effort needed for developing a detailed business plan can be invested with higher chances of successful return on that investment. In essence, exploring multiple business models before committing to a business plan opens wider options for the strategy of the organization. Figure 11.1 shows the phases of business design evolution and the types of iteration that are appropriate at each phase.

Exploring Alternative Business Models

Osterwalder and Pigneur introduced business model patterns, which are generic representations of business models with similar properties, for example, the Long Tail or the Multi-Sided Platform. They are similar to templates in word processing. Overlaying various business model patterns onto the Canvas of the current business model and considering the result enables the exploration of alternative business models. It is a what-if type of approach that helps rapidly define candidate alternative models for the organization as a whole or for a specific product or service. The next step is to evaluate these candidate models and to fine-tune promising ones.

After a business model has been deemed interesting for further consideration, it must be validated. The validation usually has two major components: Customer Validation and Model Viability.

Customer Validation is part of the Customer Development Model proposed by Steve Blank.3 It aims at validating that there is actually a customer segment willing to pay for a specific value proposition. The concept of customer validation uses teachings of Design Thinking, which revolve around the idea of small iterations for rapid learning in the process of solving a problem. In business models lingo these iterations are called pivots. In the next chapter David Charron introduces in more detail the concepts of Customer Development Model and the techniques of pivoting.

Model Viability has a qualitative aspect and a quantitative aspect. The qualitative part aims at understanding the risks and opportunities of the proposed business model and the quantitative part focuses on validating its financial viability. The former applies evaluation techniques familiar from management science such as SWOT analysis and the Four Actions framework to assess the business model. If you are familiar with the Blue Ocean strategy framework, you can also blend it with the Business Model Canvas to assess the model from yet another perspective.

The validation of financial viability of the business model verifies that the value proposition that a customer segment is willing to pay for can actually be delivered while making a profit. At this stage this validation is usually done with a summary quantification of all operational costs and revenues related to the model (Canvas elements 6–8 and 1–4, respectively) and comparison of the total revenues and costs (Canvas elements 5 and 9) to establish whether the difference is positive (profit) or negative (loss).

The purpose of Model Viability is to support a decision as to whether this model should be further pursued and developed or would be better dropped. Only models with validated customers and viability would be further developed through a detailed business plan. Note also that the three elements of business model validation (customer, risk, and financial viability) are interrelated. Consequently, the validation process is not necessarily a linear process but rather an iterative process not unlike the pivoting concept. For example, if the customer side cannot be validated, it would cause changes in the value proposition or customer segments. If the risks and threats related to a business model prove beyond the tolerance of the company’s governance, it might cause changes to multiple elements in the model to mitigate these risks and threats or lead to disregarding that model altogether. If the financial viability cannot be validated, it can cause the company to reconsider pricing points, customer segments, and/or cost elements. The point is that through rapid small iterations of business modeling, you are able to explore a larger number of possible models, rapidly evaluate the alternatives, and support evidence-based decision making in the selection of the most promising business model for further development and implementation.

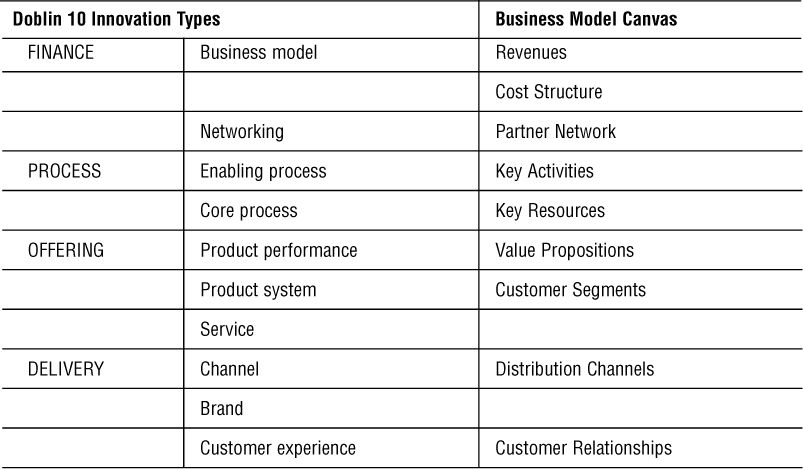

It is important to understand that business modeling allows innovation across all categories of innovation, not only in the business model itself. Table 11.1 roughly maps Doblin’s ten categories of innovation4 to the nine elements of the Business Model Canvas.

The Canvas allows an integrated view and consideration of innovations across the multiple categories by enabling a visual overview of the interdependencies among them. Whereas the Doblin chart reminds us of all the areas available for innovation outside of the traditional product/service innovation, the Canvas forces us to consider the mutual interdependencies of these potential innovations.

Limitations of the Canvas

With all its qualities and advantages, the Business Model Canvas does have certain limitations. These come primarily from the context in which it is applied and secondarily from the design of certain Canvas fields.

To understand the context limitations, consider the external environment that Osterwalder and Pigneur present for their Business Model Canvas.5 It includes four broad categories that translate to about 20 more detailed external influencers of the business model, all of which are relatively complex and interdependent. The challenge of considering such a large set of factors influencing the model often leads in practice to examining only the current or near-term status of these factors and frequently only a subset of them. And yet unanticipated change in any of these external factors would have significant impact on multiple elements of the business model, if not all of them.

In addition, near-term projections of the future of a certain factor tend to be a linear extrapolation of its present state. There is ample evidence that complex systems such as micro- and macro-economy, markets, and climate develop in a nonlinear fashion. The gap between the linear projection traditionally used for evaluating a business model and the nonlinear development that is likely to occur introduces a significant element of risk that is not accounted for in the traditional validation of business models.

To mitigate such a risk, it is necessary to explore the future a little further than is the current practice of most organizations. Such explorations fall in the domain of foresight, which builds on the collection of signals of change, even presently weak ones; analysis of trends emerging from these signals; understanding the deeper drivers of the trends; identifying the most critical drivers and uncertainties for a specific organization; and building comprehensive projections of the future, usually in the form of multiple plausible future scenarios. These scenarios are then used to explore potential implications for the business plan and the organization’s strategy in order to determine what actions and decisions in the present are needed to make both more resilient to any of these scenarios.

Discussing foresight applications is beyond the scope of this book; more information is available in the “Glossary and Resources” section. Suffice it to say that using foresight extends the time horizon of the risk assessment and can uncover substantial threats but also great opportunities for innovative business models.

Another limitation when evaluating business models is that the Canvas is focused primarily on risks and rewards in financial terms. It is widely accepted today that there are multiple other types of capital (natural, human, social, and intellectual) that are essential for the success and sustainability of any organization and therefore need to be considered when assessing business models or developing business strategies.

The recognition of the critical role of these other types of capital and their increasing volatility has raised awareness that there are invisible but potentially substantial risks for business related to the company’s interaction with social and natural capital. These risks are not limited to the business model but extend to the viability and valuation of the organization. What is the viability of a business whose majority of assets is in a location threatened by frequent severe weather events? What is its valuation if it is in an area with frequent disruptive civil unrest or running out of water resources?

Toward More Sustainable Business Models

The need to mitigate the newly uncovered risks generated interest in new measures and tools to assess the viability of a business model when additional types of capital other than financial are included in the risk considerations. There is today a large body of literature and practitioners that advocates the use of the Triple Bottom-line approach, which takes into account costs and revenues in all three major capital categories: financial, social, and natural.

It was only logical that the first attempts to create new tools capable of accommodating the Triple Bottom-line approach were to adapt the widely used Business Model Canvas for that purpose. Osterwalder himself started the quest in a 2009 lecture in Bremen, Germany, where he presented suggestions on “how to systematically build business models beyond profit.” Most practitioners of the Canvas, who are interested in sustainable business models, chose initially to add two new elements below Canvas element 5 (Revenues) that would capture social and ecological revenues and another two elements below Canvas element 9 (Cost Structure) that would capture social and ecological costs. An example of such adaptation is the Extended Business Model Canvas by Vastbinder et al.,6 shown in Figure 11.2.

Although such additions proved useful in uncovering business model patterns, particularly in the context of low-income economies, the main challenge remained generally the measurement of social capital and its quantification in economic terms. These challenges are being addressed by advances in the Social Return on Investment (SROI) theory, as well as through emerging methods and systems for measuring and tracking social assets that are rapidly accumulating experience in selecting appropriate measures for social assets and developing financial proxies for their economic valuation.

Frameworks for Sustainable Business

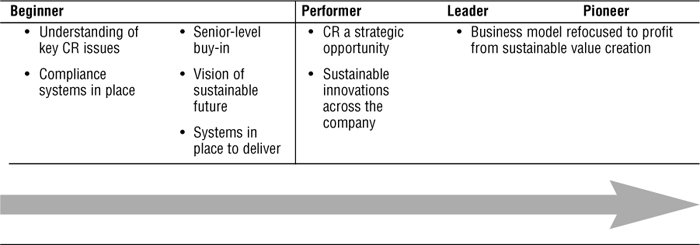

In parallel to the efforts of adapting the Canvas, several frameworks emerged for the “greening” of the business model. In Table 11.2, one such framework is proposed.

Table 11.2 Sustainability Maturity Stages (Materials Made Available Courtesy of the Forum for the Future)

The Forum for the Future is developing a framework for sustainable business that integrates the various maturity stages as shown in Table 11.2: Beginner, Performer, Leader, and Pioneer.

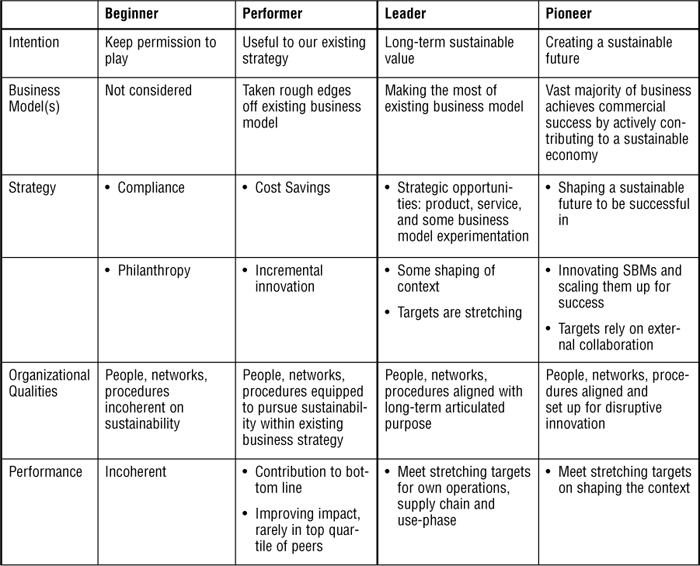

As shown in Table 11.3, the framework also identifies the characteristics of each of these stages as they relate to intention, business models, strategy, organizational qualities, and performance. A link to the Forum for the Future is provided in the “Glossary and Resources” section of this book.

Table 11.3 Sustainable Business Framework (Materials Made Available Courtesy of the Forum for the Future)

There are several other frameworks all intended to provide guidance for companies that want to begin the transformation toward a sustainable organization, for example, the five levels of sustainable activities proposed by The Natural Step7 or the Gearing Up Framework proposed by Avastone Consulting, headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia.8

At the leading edge of this broad spectrum of frameworks and approaches to sustainable business is the Strongly Sustainable Business Model Group (SSBMG), based at OCAD University’s Strategic Innovation Lab in Toronto, Canada. Strong sustainability is a term coined by ecological economists and is centered on the axiom that it is impossible to replace natural capital with any other type: human, social, or intellectual. SSBMG is taking a design science approach to developing tools and methods helping small and medium-sized enterprises to shift toward a strongly sustainable mode. Starting from Osterwalder business ontology and Canvas, Antony Upward, co-founder of SSBMG, has developed SSBM Ontology and SSBM Canvas, which in mid-2013 were being tested with several organizations.

The Business Case for Sustainability

In the past decade since the sustainability question entered mainstream thinking, the general assumption among business leaders has been that “sustainability” implied a trade-off between financial performance and so-called ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) performance. Many business leaders saw it as a necessary action at the cost of their organization’s performance. In the past few years research has uncovered a direct linkage between sustainability and corporate risk management, as well as links related to access to capital. More recently, evidence has emerged that applying sustainability principles actually improves the company’s bottom-line performance. In his most recent book, The New Sustainability Advantage,9 Bob Willard has compiled business cases covering a large manufacturing company as well as a small service company. His business cases demonstrate seven benefits that make sustainability strategies smart business strategies:

1. Increased revenues and market share

2. Reduced energy expenses

3. Reduced waste expenses

4. Reduced water and materials expenses

5. Increased employee productivity

6. Reduced hiring and attrition expenses

7. Reduced risks

Willard offers free online access to the same calculator he used for the business cases in his book, so you can enter the data of your own organization and figure out how to optimize sustainability’s impact on the bottom line. A link to this calculator is offered in the “Glossary and Resources” section of this book.

Where to Go from Here

It is obvious that developing a sustainable business model is a process, whose scope and complexity depend on many factors including the maturity of the company in its understanding of the imperative for this broader sustainability approach. Developing sustainable business models requires managing risks in the new arenas of natural and social capital. It also usually requires broader participation across the organization and attention to the culture and structure of the organization and its learning capacity. Implementing sustainable business models encompasses a wider range of change within the organization, as well as in its external network, than traditional business models.

A good starting point might be assessing your organization’s position on the maturity scale using one of the frameworks presented earlier. Next, review the business cases presented by Bob Willard and explore how you can apply these principles in your organization to improve your bottom line. Now chart a path moving your organization to a higher level of maturity. A checklist of actions to do so is offered by the eight steps recommended by the Green Business Model Innovation,10 a collaborative research project of Nordic Innovation. The eight steps are best practices toward green business model innovation:

1. Develop company culture toward sustainability.

2. Frame company values and translate them into principles or business practices.

3. Implement green strategy: a vision and mission linked to all activities of the organization.

4. Acquire appropriate skills and knowledge across the value chain through external resources and internal training.

5. Create green business cases: Green business models must be financially sustainable.

6. Involve customers to better understand their needs and expectations of a sustainable company.

7. Start small to experiment and learn before scaling up.

8. Train sales staff to communicate the company’s values, products, and services in a credible way to customers.

With that foundation you can then explore new and alternative business models, taking into consideration the Triple Bottom-line approach using tools such as the Extended Business Model Canvas or the soon-to-be-available Strongly Sustainable Business Model Canvas and its tool kit.

Endnotes

1. A. Codrea-Rado, “Until the 1990s, Companies Didn’t Have ‘Business Models,’” April 17, 2013, accessed July 25, 2013, http://qz.com/71489/until-the-nineties-business-models-werent-a-thing/.

2. A. Osterwalder and Y. Pigneur, Business Model Generation (self-published, 2010).

3. S. G. Blank, The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products That Win (2007).

4. L. Keeley et al., Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs (John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

5. A. Osterwalder and Y. Pigneur, Business Model Generation.

6. B. Vastbinder et al., “Business but Not As Usual: Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development in Low-Income Economies,” in Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Sustainability, ed. Marcus Wagner (Greenleaf Publishing, 2012).

7. “A Strategic Framework,” The Natural Step, accessed July 25, 2013, www.naturalstep.org/en/our-approach.

8. C. A. McEwen and J. D. Smith, Mindsets in Action: Leadership and the Corporate Sustainability Challenge (Atlanta, GA: Avastone Consulting, 2007).

9. B. Willard, The New Sustainability Advantage (New Society Publishers, 2012).

10. T. Bisgaard et al., Short Guide to Green Business Model Innovation (2012), available from www.nordicinnovation.org/Publications/short-guide-to-green-business-model-innovation/.